Abstract

This paper focuses on the initial “spark” of the design process, in which Drawing, Image, Language intertwine and/or prevail over each other. The possible and ideal meeting point of these three concepts has been identified and recreated within the International Competition IBA 84; which represents a suitable model for comparing different strategies; personalities; and design methods. The designers, carrying out a series of rational and poetic researches in areas often apparently detached from architecture such as philosophy, art, music and literature, need a medium that gives shape to their concept. This medium can be recognized in the representation. Aim of the research is to highlight the relationships between project concept and representation techniques.

1. Introduction

“I aimed the fidelity of thoughts so that, clearly generated by the observation of things, they turned, almost spontaneous, in the acts of my art … what I think can be done, and what I do is intelligible” [1] (p. 18).

Each architect, in order to formulate a design solution (the idea), relies on the most varied means, carrying out a series of rational and poetic researches in areas often apparently detached from architecture such as philosophy, art, music and literature.

The medium that gives shape and express these concepts is the representation.

During this phase, the architect made different type of design documents: some represent the designer’s dialogue with himself (representation as introspection or autograph representation)—i.e., sketches, scale model, photo collage, renders and currently, thanks to the tools offered by the digital revolution, also the writing of generative algorithms; others, in which the representation, nowadays flanked by digital models, animations, immersive experiences, become the mean of communication between the designer and the mankind (representation as communication or representation addressed to others).

Generally, the phase of the representation is the heuristic moment of the project in which the architect, free of budget, program and politics constraints, draws signs in a fast and instinctive way, shapes real or digital forms, develops and composes images and photographs that contain what the project will be, what it will not be, what it could have been and all the references accumulated over time in his mind.

The gradual reworked version of these first representations will lead to a clearer and more precise definition of the project. The distance between architectural thinking and its ambition to become reality can gradually decrease.

This paper focuses on the initial “spark” of the design process, in which Drawing, Image, Language intertwine and/or prevail over each other.

The possible and ideal meeting point of the three concepts has been identified and recreated within the International Competition IBA 84, which represents a suitable model for comparing different strategies, personalities and design methods.

In this context, there are three architects, Aldo Rossi, Rem Koolhaas, and Peter Eisenman, called with others to carry out a series of concrete interventions for the “critical reconstruction” of the city of Berlin, that seem to be able to embody, with their poetry, each of the three concepts.

The three different design approaches that emerge are: the emotional approach of Aldo Rossi, in which reference models belong to a dreamed and metaphysical world, that enhances emotions, recalls and memory; the programmatic method of Rem Koolhaas, where what really matters are the current events and the response to the needs of the global community; and finally, the theoretician approach of Peter Eisenman in which concepts of Existentialism are applied to architecture.

The graphic works produced by the three authors in response to the competition requests concern the communication scope. The analysis and the critical synthesis of their proposals for IBA 84 carried out by the authors are based on the study of their theoretical assumptions and their speculative and professional career, using the tools of representation suggested by the cognitive path practiced on each of the three: the drawing, the collage-montage, and the layering.

As it will see Drawing, Image, Language affirmed themselves in their specifics and in their dialectical relationship.

2. Finding the Scenario: The Critical Reconstruction of Berlin City

Since 1974, the German architect Joseph Paul Kleihues, directed and organized an important international architecture exhibition in Berlin: the Internationale Bauausstellung (IBA), that aims to carry out a series of interventions, real and exemplary, proposed by the most important contemporary architects and emerging young people.

In particular, IBA 84, according to Kleihues, focuses on the “critical reconstruction of the city” [2] (p. 129) that in his vision must resume and re-propose the urban form of the traditional city.

The postmodernist theories—claimed in the second half of the Seventies, through the thought of the architects: Vittorio Gregotti, the brothers Leon and Rob Krier and the same Kleihues—join the analysis of the space of the traditional European city and the quit mimetic reproposal of the forms that characterized it. The street, the square and, above all, the perimeter plot are the protagonists of master plans and urban projects of that architectural movement.

As Cassetti remembers “in the 1980s Berlin became a real international forum for debate on the space rules that so far had ruled the composition of the city and the discussion of the Modernism’s fundamentals” [3] (p. 120). Kleihues and Siedler, having started and directed the debate since 1977 on the Berliner Morgenpost newspaper, in IBA 84 promoted a unitary plan for the Innerstadt.

IBA 84 propose to take on the oldest parts of West Berlin, partially destroyed by the war and later overlooked by urban planning or modified according to the principles of the Modernism, considered by Kleihues just as destructive.

The Exhibition becomes a great and ambitious attempt to renew the traditional city, to rehabilitate or rebuild the blocks, to restore or redesign them. The aim is to modify the traditional city to make it adapted to the new housing needs. The IBA 84’s subtitle is indeed “Living in the City Center”.

Rossi, Koolhaas and Eisenman work with others in the Südliche Friedrichstadt area, one among the many intervention area proposed by the competition.

This homogeneous part of the city is characterized by a dense regular network of streets and a constant repetition of perimeter blocks.

Despite post-war up reconstruction, Kleihues was able to read the original plan’s strength with a view to rebuild it through the proposals of the competitors, who are asked to project on a circumscribed intervention to the size of the block.

In the call there are two essential rules: the continuity of the urban alignment and the size of the road network and the reconstruction of continuous façades in the perimeter blocks.

3. Poetics and Design Techniques: Three Comparing Masters

In this scenario, among many participants, were compared the designing processes of three architects: Rem Koolhaas, Peter Eisenman and Aldo Rossi.

The survey focuses about why, three different personalities can coexist within the same context, giving answers and using different design approaches, compositional choices and architectural poetry. In particular, the analysis is based on the interweaving between the poetry and the design techniques used by the three to bring out, express and communicate their idea about the critical reconstruction of the Berlin center.

All three have in common a rich and intense theoretical activity that led them to important texts’ publication, real milestones of architectural thinking, from the Sixties of the Twentieth century. Their ideologies deeply influenced their design choices.

3.1. Aldo Rossi, the Drawing for the Expression of the Concept of Architecture

“The most important thing in the work of an architect is to give an idea: … Architecture born from a image, a precise image that has fallen deep within ourselves and that translates precisely into drawing and construction. The most important moment is really the idea of architecture. Only when you have this idea you can begin to draw it and, therefore, to perfect it” [4] (p. 116).

For the residential unit at the corner between Kochstraße and Wilhelmstraße, Aldo Rossi starts a careful study and a selection process of pre-existing models in the Berlin architectural tradition by looking for the founding element of the site. This element is named “genius loci”, where the locus is “the singular and universal relationship which exists between a certain local situation and the buildings that are in that place” [5] (p. 139).

He pays particular attention on the road axis’s restoration, taken as an ordinating element, on the buildings average height along Friedrichstraße, important for the achievement of the perspective continuity, on the recurrent architectural elements and on the typical building materials.

The building of Aldo Rossi is characterized by a strict geometric composition in which transparent glass glazed bodies shall be alternated to opaque brick parallelepipeds with regular square windows.

The porches on the ground floor and the accesses to the internal courtyards make the building permeable. As in the past architectures, this allows to see the inner courtyards from the street.

The façade is rhythmic by the pitched roofs realized with green copper and the triangular pediment placed on the bodies of vertical distribution. These elements contribute to spice up the façade, breaking up the horizontality of the cornice.

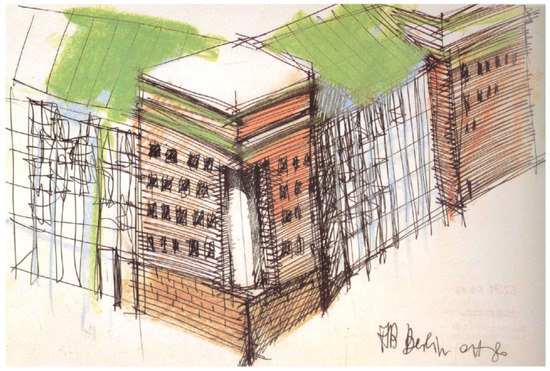

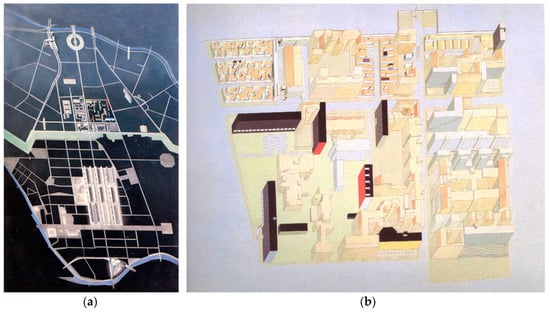

A massive white column on the ground breaks the edge of the building, making it recognizable into the urban fabric (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Aldo Rossi, plate for IBA 84. Sketch of the building at the corner between Kochstraße and Wilhelmstraße, Block 10, 1981.

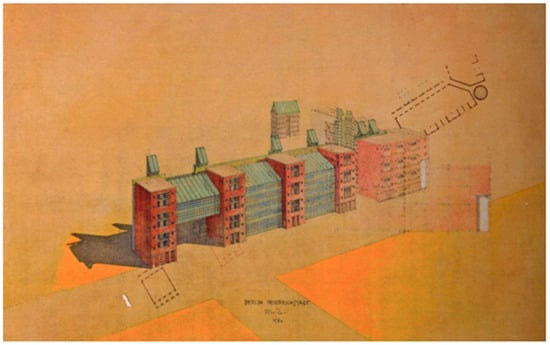

Figure 2.

Aldo Rossi, plate for IBA 84. Plan and axonometry on Wilhelmstraße, Block 10, 1981.

In Aldo Rossi’s theory, the architecture must be transformed into a positive science serving the community; the city is an artifact, a work that grows and changes over time, to be examined and analyzed by parts. Each element, if classified and cataloged, can lead to the idea, to the drawing and to the construction [6] (pp. 92–93).

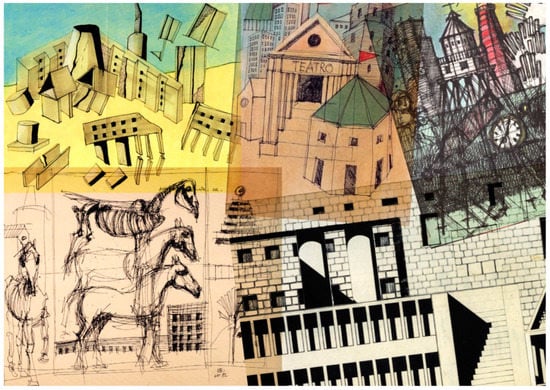

In the design process, knowledge and objectivity are insufficient if not alongside a subjective approach that takes into account emotions, experiences, recalls and personal memories. In his drawings, influenced by the metaphysical painting of De Chirico, Carrà, Morandi and American artists such as Hopper and Rauschenberg, the architectures are made as geometric primitives (parallelepipeds, pyramids, cylinders, cones, spheres) and combined with flat figures (squares like windows, triangles like pediments). Between them appear old tapestries, coffee makers, cigarette packs, Coca Cola cans … and other elements from literature, cinema and photography.

Thanks to the combination of these elements within its sketches and preliminary drawings, his architectural compositions and concept of space take on a meaning, becoming the essence of his architecture.

The expressive intensity of these drawings is made up by strong color contrasts and by the wise use of the pictorial techniques such as tempera, wax, engraving, collage and dense china textures, used to give a perceptual effect and to suggest the possibility of building the object.

In his metaphysical compositions, made of flat figures and elementary geometric shapes combined with architectural elements—cones, cubes and cylinders that become chimneys, squares, and theaters—already stays the main thrust of the project (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Aldo Rossi, sketches. Collage by Giulia Bertola.

Aldo Rossi, in fact, states: “I have always a short period of meditation on the project: I try to bring back a core of impressions: it is what is developing. I don’t usually modify my projects, I think it never happened. My first sketches are extremely similar to the final project. During the first part of the design process, graphic communication is very important to me” [7] (p. 17).

Maybe it is for this reason that the master submits among the required competition materials for IBA 84, his sketches along with the final drawings.

The importance of the drawing in Aldo Rossi’s design process brought to consider the re-draw, intended as a critical retrace of the project, the most effective representation system aimed to the analysis.

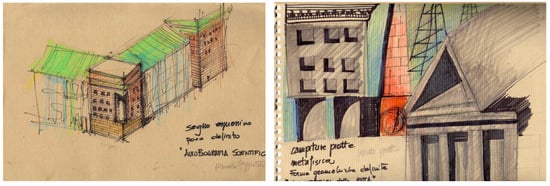

To obtain a more precise reading of Aldo Rossi’s IBA 84 project, reproductions, reflections, re-workings, compositions—all inspired by Aldo Rossi’s drawings and texts pages—have been gathered in a sketchbook. It was a good way to investigate the overall work, coming to a comprehensive reading of the project for IBA 84 (Figure 4). Drawings made of a colored pencils and oil pastels on drawing paper allow Aldo Rossi to approach manual practice: the hand that lays the pen on the paper, leaving measurements, proportions and rulers, and makes spontaneous and instinctive signs emphasized by the use of color, almost as if the intention was to compose parallel worlds, childish illustrations, and memories that each of us carries within himself.

Figure 4.

Giulia Bertola, interpretative sketches of Aldo Rossi’s drawings.

Going beyond the reading of texts and trying to fall into these gestural practices allowed, during the study phase, to achieve in a more direct and incisive way to a deeper understanding of his “making architecture”.

3.2. Rem Koolhaas, the Image to Redefine the Project Idea

“Berlin is a lab, its territory is defined and for political reasons it cannot be reduced. The population, from the wall construction, is steadily declining. So few people occupies this metropolitan territory. Many parts of the city are in ruin because they don’t meet the people needs” [8] (p. 157).

Rem Koolhaas is present in two projects for IBA 84: one on the four blocks on the corner between Kochstraße and Friedrichstraße; the other, supervised by his partner Elia Zenghelis, in Lutzowstraße.

The first one, unrealized, is the subject of the current analysis.

Koolhaas is in contrast with the terms of the call; he contests the city model proposed and puts the focus on elements overlooked.

He states that “the wealth of the city of Berlin born from the experimental succession of various models: neoclassical city, metropolis in formation, cradle of Modernism, capital of Nazism, victim of war, Lazarus, battlefield of Cold War” [9] (p. 154).

He refuses the Kleihues’s reference to a single city model: the Nineteenth century traditional city. His proposal, attentive to the present, is an architecture that meets the needs of the global community.

In the bird’s eye view that presents his proposal for intervention, he recovers suggestions excluded from the call: the voids made by the bombings, the post-war reconstructions and, above all, the Wall, which encloses and divides the city and the architecture of Berlin.

The architect also introduces two Modern Movement’s unrealized projects: the skyscraper by Mies van der Rohe in Friedrichstraße (1921), the block-building complex on the same street by Ludwig Hilberseimer (1928), and a partially completed building, the seat of the German Metallurgic Federation, by Erich Mendelsohn, in the nearby Lindenstraße (1928–1929).

This plate exalts the value of the plan, kind of representation in the center of attention by the Modern Movement. In the same way, the following drawings, that define the functional program for the four plots, start from the undeformed plan from which the three-dimensionality of the artifacts is developed in axonometry (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Rem Koolhaas, OMA, plates for IBA 84. (a) Bird’s eye view; (b) Axonometric view of Blocks 4, 5, 10, 11, 1980.

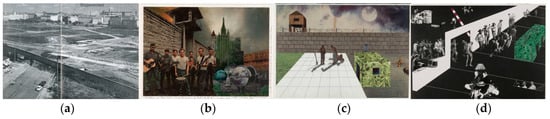

The architect in the project overlooks the indications of the call: in one of the blocks doesn’t respect the perimeter edification and puts freely all the buildings inside the lot; in another block proposes courtyard houses with a different height compared to the existing buildings, that become “post-war wrecks” [8] (p. 50). These houses also create a series of walls: a symbolic reflection of the Berlin Wall. The Wall, shouldn’t be demolished and turned into a park band with Zen sculptures with villas around it (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Rem Koolhaas and the Wall. (a) Photo from S, M, L, XL, 1977; (b) Photo-montage from Exodus, 1972; (c) Allotments, from Exodus, 1972; (d) Photo-montage from Exodus, 1972.

He observes that “IBA erases this evidence by destroying, in the name of history, the very evidence of destruction itself, which is perhaps the most significant fact of the city’s history, not to mention its aesthetics” [10] (p. 154).

Under IBA 84, Koolhaas’s focus on the Wall, a symbol a Cold War having a strong emotional, social and cultural impact throughout the world, resumes the subject of his 1971 Summer Study “Berlin Wall as Architecture”. The Wall becomes a symbolic element that cuts houses, streets and squares like the razor cutting the woman’s eye in the movie “Un chien andalou” by Buñuel and Dalí.

In the following year, 1972, the Utopian project “Exodus, or the voluntary Prisoners of Architecture” conducted with Zenghelis in response to the competition “The City as a Significant Environment” promoted by the Association for Industrial Design in collaboration with Casabella, develops a proposal that overrides the meaning of the Wall.

Exodus is an ideal city structure, designed for the center of London, where the “intense and devastating force” [11] (p. 7) of the Wall is used for positive purposes: two parallel walls enclose a system of articulated squares where different activities take place, attracting the exodus of the population from the historic city.

As in his theoretical writings, also regarding the Wall, Koolhaas shows his distance from drawing as a mean of representation, to the point of delegating to his wife the drawing of plates. Meanwhile he produces a series of images that shows his tendency to use photo-montage to express his concepts, thoughts, positions and messages to the mass. These collage-compositions of drawings, photographs, newspaper clippings correspond to the concept expressed by Salvador Dalì in 1963, of “paranoid critical interpretation” [12] (p. 190) as they arise from the agitation of the author’s unconscious, his paranoia, and can only take shape by the rationalization of delirium through the critical moment.

Engaged in the fields of theater, cinema, painting and fashion, as well as architecture and architectural theory, its communication techniques are influenced by Russian Constructivism, where art assumes the value of information, and Pop Art, with its critical rehabilitation of media, icons and phenomena present in the mass imagery: advertising, comic, consumer goods, and star portraits.

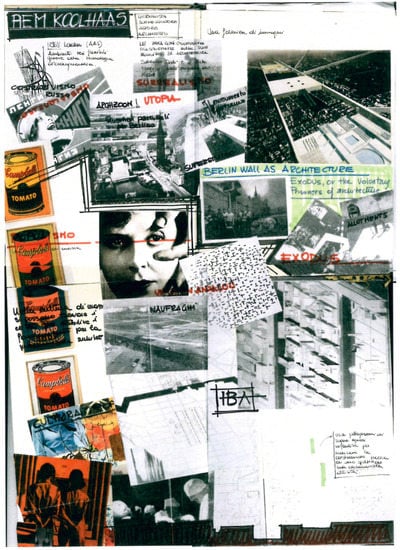

Two main elaborations featured the analysis and synthesis of Koolhaas’s design motives for IBA 84.

The first one is a manual collage, a study tool made of images drawn from the historical, artistic, political, social, and architectural context in which IBA 84 is inserted. In order to understand the design practice of Koolhaas it was necessary to fit into this context by neglecting the rules issued by the call and gathering images, information, and articles that can influence on it (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Giulia Bertola, Analytic interpretative collage of Koolhaas’s competition entry for IBA 84.

The second one is a digital collage that repurposes the page of a real newspaper, with different titles sizes (to emphasize the priority of various informations) and slogans to briefly explain the images of current events or artistic movements that are powerful on the people. The story of his work was interpreted as a set of newspaper articles, able to form a unitary speech (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Giulia Bertola, Synthetic interpretative collage of Koolhaas’s competition entry for IBA 84.

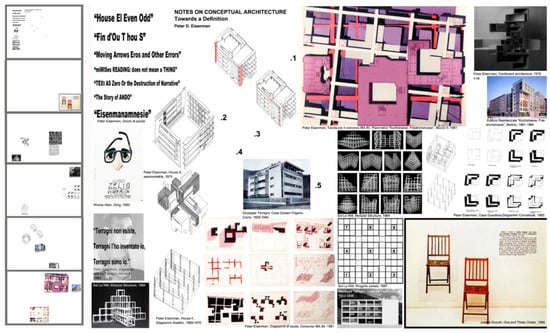

3.3. Peter Eisenman, the Language for Building the Design Process

“A diagram can be seen in architecture as a dual system that works as a writing instrument both in the exterior and in the interior of the architecture and in relation to the requirements of a specific project … the diagram acts on a surface receiving inscriptions from memory of what still does not exist, that is, the memory of a potential architectural object... the diagram works as an agent that focuses on the relationship between an author subject, an architect and a recipient subject, this is the layer between them” [13] (p. 200).

Peter Eisenman deals with the theme of residential building on the corner between Kochstraße and Friedrichstraße, next to the Wall, a few meters from Checkpoint Charlie. He states that “our strategy was twofold. Our first aim was to highlight the particular story of the place, which meant to give visibility to its specific memories, to recognize that at some point this was a very specific place. The second was to recognize that today Berlin belongs to the world in the broadest sense of the word” [14] (p. 74).

The project is set up on different levels to which different historical tissues correspond to: the Eighteenth-century wall, the Nineteenth-century foundations, the Twentieth century streets network and the Wall.

They run from bottom to top to create the building. The purpose is to refer not only to the urban plots of ancient Berlin, but also to a wider plot that goes beyond the other: the grid of Mercator [14] (p. 108), conceptually linking Berlin to the universe. This grid initially engages the historic axis of the Friedrichstraße, but as it progresses, it becomes more and more an autonomous element rising to a height equal to that of the Wall, reducing its importance.

Eisenman tends to favor the urban mesh and the internal intersections, focusing on corner spaces. These form an L shape with a rotation symmetry set at the vertex. This system, used from the plan, spreads to the elevations. The L shapes move back and forth along vertical planes creating overlaps and cancellations [14] (pp. 104–108).

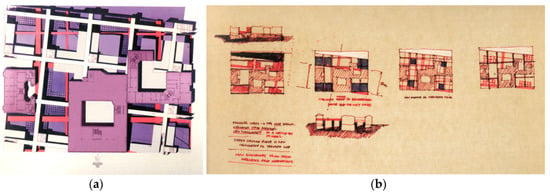

The relationships with the context arise through the recovery of the Nineteenth-century fabric in the shape of the building, whose mesh is rotated by 15° compared to the current one. In this way, the architect can summon the place’s properties without resorting to camouflage architecture (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Peter Eisenman, plates for IBA 84. (a) Plan view of Block 5; (b) Sketches, 1981.

As Aureli, Biraghi and Purini point out, in this project Eisenman attempt to confront the context and the themes related to place, memory and collective values.

With regard to the first two, he reasons on the concept of ‘archaeological digs’ aimed at dissecting the stories of the places and discovering their old abandoned geometries by using the blueprint, a graphical tool consisting of space lattices (complex layered and overlapping grids similar to medieval palimpsests). The textures and the lattices must re-emerge thanks to an excavation process. In fact, he acts as “an archaeologist who, with his imagination, digs into the place and tries to understand the past and reinterpret it” [15] (p. 104).

Concerning the collective values, the architect adopts the instrument of metaphor: architecture, while retaining its abstract value in the relationship between sign and meaning, becomes capable of narrating a story; a metaphorical process that becomes for him a real way to build [15] (p. 34).

The tear found at the intersection between Kochstraße and Friedrichstraße and the intersection between the latter and the Wall become visible “both in the paths with which the elevation is shaped and in the dynamic fragmentation of the masses” [15] (p. 34).

The design method of Peter Eisenman uses a theoretical approach that applies the concepts of philosophers such as Noam Chomsky and Jacques Deridda to architecture, and is influenced by Conceptual Art and Minimal Art, with particular reference to Joseph Kosuth’s and Sol Le Witt’s thinking.

Approaching Chomsky’s linguistics involves the assumption of the concept of architecture as a text whose references can be found within architectural logic and, at the same time, deployed within other systems of thought [15] (pp. 10–11). In this sense, images, signs and shapes can be translated into words.

The attention to the design process emerges in his work: the project is explained through the sequence within the time that generated it. The object alone does not communicate the intentions. One of the tools to make ideas visible while leaving a trace of the project process is identified in the diagram.

The diagram, understood as a “set of lines and paths … serves to clarify a meaning, to demonstrate an affirmation, to represent the occurrence or the outcome of any kind of action or process” [16] (p. 19). Eisenman’s diagrams are axonometries that illustrate the evolutionary and generative steps of the work.

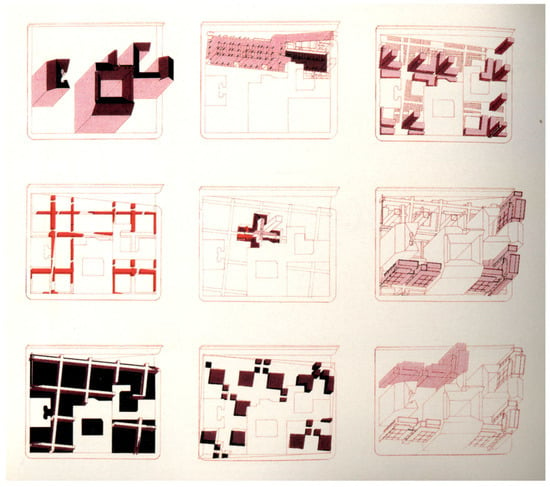

The diagram emerges as a project design tool also in the IBA 84 plates, allowing the author to relate the stratification of the road networks emerged from the ‘archaeological excavation' operations, with the new proposal (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Peter Eisenman, plate for IBA 84. Study diagrams.

For the interpretation of IBA 84 project, we have used a set of layers that overlap each other to determine a complete picture of all elements, which are the foundation of his design philosophy. The interpretation using the layers also allowed dividing the stages of his design path. These stages are determining to investigate the approach he takes in the IBA 84 competition (Figure 11). Once collected, the information has been reported on the graph paper, a useful method to have a ruler element (the square) that conveys the tracking of the signs (sketches and notes); then others information have been added through the use of acetate paper.

Figure 11.

Giulia Bertola, Layering and synthetic interpretative plate of Eisenman’s competition entry for IBA 84.

At a later stage, such information was digitalized and printed on a glossy paper: each page represents a part of the manuscript and a specific issue; overlapping them with the others, they go to add information and meaning and the speech takes shape in its entirety.

The architect decides according to his will as a means of representation to use. The goal is to best express his design intentions. Every method of representation is the result of the importance of design research.

4. Conclusions

As we have seen, by taking the Architectural Competition as the ideal place for convergence of different design strategies, it is possible to analyze different proposals, retracing the theoretical training path and the experiences of different masters, using to the critical filter of the relationships between project and representation. In this sense, the techniques of representation, influenced by the multifaceted artistic experiences of the three architects examined, manifest their own not-neutrality with regard to the processuality of the project. In fact, the representation techniques intertwine with the design process, becoming a powerful heuristic instrument.

The analysis of the presented projects proposed subjective hypotheses aimed at revealing motives, objectives, values and design meanings, using the techniques suggested by an in-depth knowledge of the cultural substrate of the three masters.

The keywords identified to define different strategies: Drawing for Aldo Rossi, Image for Rem Koolhaas, Language for Peter Eisenman, are the ideal fil rouge between design poetics and carefully selected interpretative tools.

Author Contributions

This paper originates from the subject of thesis in Science of Architecture, presented by Giulia Bertola at the Politecnico di Torino in 2011, under the guidance, as supervisor, by Roberta Spallone. A series of meetings, interviews, exchanges of opinions and insights in the following years led to the joint writing of this essay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kleihues, J.P.; Klotz, H. International Building Exibition Berlin 1987; Example of a New Architecture; Academy Edition: London, UK, 1986; pp. 128–129. [Google Scholar]

- Cassetti, R. La Città Compatta: Dopo la Postmodernità; I Nuovi Codici del Disegno Urbano; Gangemi: Roma, Italy, 2016; ISBN 9788849222302. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. L’architettura dell’idea. In Dialoghi di Architettura; Faroldi, E., Vettori, M.P., Eds.; Alinea Editrice: Firenze, Italy, 1995; pp. 115–125. ISBN 9788881250523. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. L’architettura Della Città, 1st ed.; 1966; Città Studi Edizioni: Milano, Italy, 1995; ISBN 88-251-7282-6. [Google Scholar]

- Moneo, R. Inquietudine Teorica e Strategia Progettuale Nell’opera di Otto Architetti Contemporanei; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 2005; ISBN 9788837029500. [Google Scholar]

- Magnago Lampugnani, V. Colloquio con Aldo Rossi. Domus 1990, 722, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, R. Immaginare il nulla. 1985. In Rem Koolhaas, Architetture 1970–1990, 1st ed.; Lucan, J., Ed.; Electa: Milano, Italy, 1991; pp. 156–157. ISBN 9788837024338. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, R. La terrificante bellezza del ventesimo secolo. 1985. In Rem Koolhaas, Architetture 1970–1990, 1st ed.; Lucan, J., Ed.; Electa: Milano, Italy, 1991; pp. 154–155. ISBN 9788837024338. [Google Scholar]

- Gargiani, R. Rem Koolhaas/OMA; Cap II, New Sobriety Contro Post Modern e Contextualism; Laterza: Roma/Bari, Italy, 2006; pp. 40–82. ISBN 9788842079286. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, R.; Mau, B. S, M, L, XL: Small, Medium, Large, Extra Large; The Monacelli Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 9781885254863. [Google Scholar]

- Dawn, A. Dalì, La Retrospettiva del Centenario; Bompiani: Milano, Italy, 2004; ISBN 9788845233173. [Google Scholar]

- Kipnis, J. Diagrammi di ri-originazione. In Peter Eisenman, Contropiede; Cassarà, S., Ed.; Skira: Milano, Italy, 2005; pp. 193–201. ISBN 9788876243776. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman, P. The city of Artificial Excavation. Archit. Des. 1983, 53, 73–103. [Google Scholar]

- Aureli, P.V.; Biraghi, M.; Purini, F. Peter Eisenmann, Tutte le Opere; Electa: Milano, Italy, 2007; ISBN 978883704493. [Google Scholar]

- Saggio, A. Peter Eisenmann, Trivellazioni nel Futuro; Universale di Architettura: Roma, Italy, 1996; ISBN 9788886498081. [Google Scholar]

- Vidler, A. Cos’è comunque un diagramma. In Peter Eisenman, Contropiede; Cassarà, S., Ed.; Skira: Milano, Italy, 2005; pp. 19–27. ISBN 9788876243776. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).