1. Background

The research looks at some aspects of the vast theme of cartographic representation, analyzing, in particular, some characteristic codes that can be traced in the history of graphical languages present in the historical maps of the Abruzzo region in order to study the objective meanings typical of maps and underlined codes that, from the middle of 1550 to the late 1800s, narrated the historical and cultural evolution of the represented context. By relating these expressive languages (codes, semantic, aesthetics) to the vast written and graphic heritage on the subject, we can detect theoretical and methodological structures through which the information contained within historical maps is put into system and organized to become knowledge and resolve the conflicts attributed to the cartographic cultural heritage, often considered uncertain and insidious by its very nature by scholars.

Through carefully looking at the historical maps selected in this research, one perceives how the “ornamental” device in support of the more purely “mapping” device demands an attention beyond the purely aesthetics consideration and conceals messages that admit and orient a different reading of paper meant as graphic text; while the cartographic image is entrusted to the technical and instrumental function of the territory, the ornament is entrusted with the task of expanding the meanings and describing with the “other words” the cultural context of reference. In this regard, the information presented in the historical maps relates to two main contexts: an objective one and a hidden one. The objective context refers to the information related to the direct relationship with the explicit space and meanings arising from the continuing need to describe the territory in order to be able to move in it—notwithstanding the representative inaccuracies that such a methodology, not supported by precise measurements, involves in the return of the information. The hidden context, however, has many affinities with the so-called “non-verbal” language; in other words, taking into account the “secret codes” of the iconographic apparatus, the intentions of the individual semantic representations convey, and this information, properly deciphered, allows us to have an exclusive advantage in understanding of the signifiers. In particular, since cartographic techniques and evolutionary aspects have been widely debated over the years, involving specialists in the matter, this research focuses on the unconventional language that gives life to new imaginative and evocative journeys.

2. Technical Languages and “Decorative” Languages. To Understand and to Interpret

The first spontaneous consideration when faced with a targeted cartographic study, specifically in the mapping apparatus, concerns the recognition of the value of non-technical iconography, that apparently takes away meaning from the knowledge of places. Imaginative filling, which at first serves to fill the uncertain notions of a geographic character and then to become a precious ornament that defines the value of the elaborates, comforts the “horror vacui” suffered by the cartographic production of that time.

Knowledge of the territory over time is the result of on site experience and every corner of the Earth experienced through the senses, assumes a likely acceptable configuration and becomes a geo-graphical testimony of the will to return as correctly as possible to the knowledge of the undiscovered places. In this regard, sensory experience has a physical and intellectual limit that corresponds, respectively, to the limitations of navigation and the discovery of new places; it is therefore necessary, from both a psychological a graphic point of view, to fill the fear generated by partial geographic knowledge. For this reason, the limits reached by direct experience naturally become imagination’s starting point. The illustrative apparatus thus assumes a renewed importance and becomes a substantial part of the experience, almost a necessary parallel instrument that describes places with a less technical language but equally rich in descriptive informations. The 1500 map carries out the explorative attitude typical of the period and the continuous discovery of new places and experiences related to land and sea travels, and creates an open and evolving graphic lap. Representations of the sixteenth century, although they begin to encapsulate an evocative sketch of real earthly conformation, in the light of the knowledge that becomes more and more concrete, are unfinished works and rich in misunderstandings. For this reason, such cartographies are perpetually waiting for new informations and where they cannot conquer them, they need to be fancied and filled up; the desire to get to unreachable places in that historical period often gives way to imagination. Since the void and the unknown create uncertainty and fear, the need for graphic comfort is felt; for this reason, while the technical representation is rapidly discredited by any new knowledge, the descriptive apparatus fills in the mistakes and gives aesthetic pleasure and a conceptual value to it that saves cartographic elaborations from negative judgment over time. The visual comparison and the theoretical parallelism between geographic and illustrative language make it possible to tell the same story, each with different explanatory codes; a paper technically depicted and pleasantly enriched by the imagery of the explorers, accompanies those who look at it for a virtual and sensory journey in places to be experienced, and at the same time invites us to go through an inner and personal exploration.

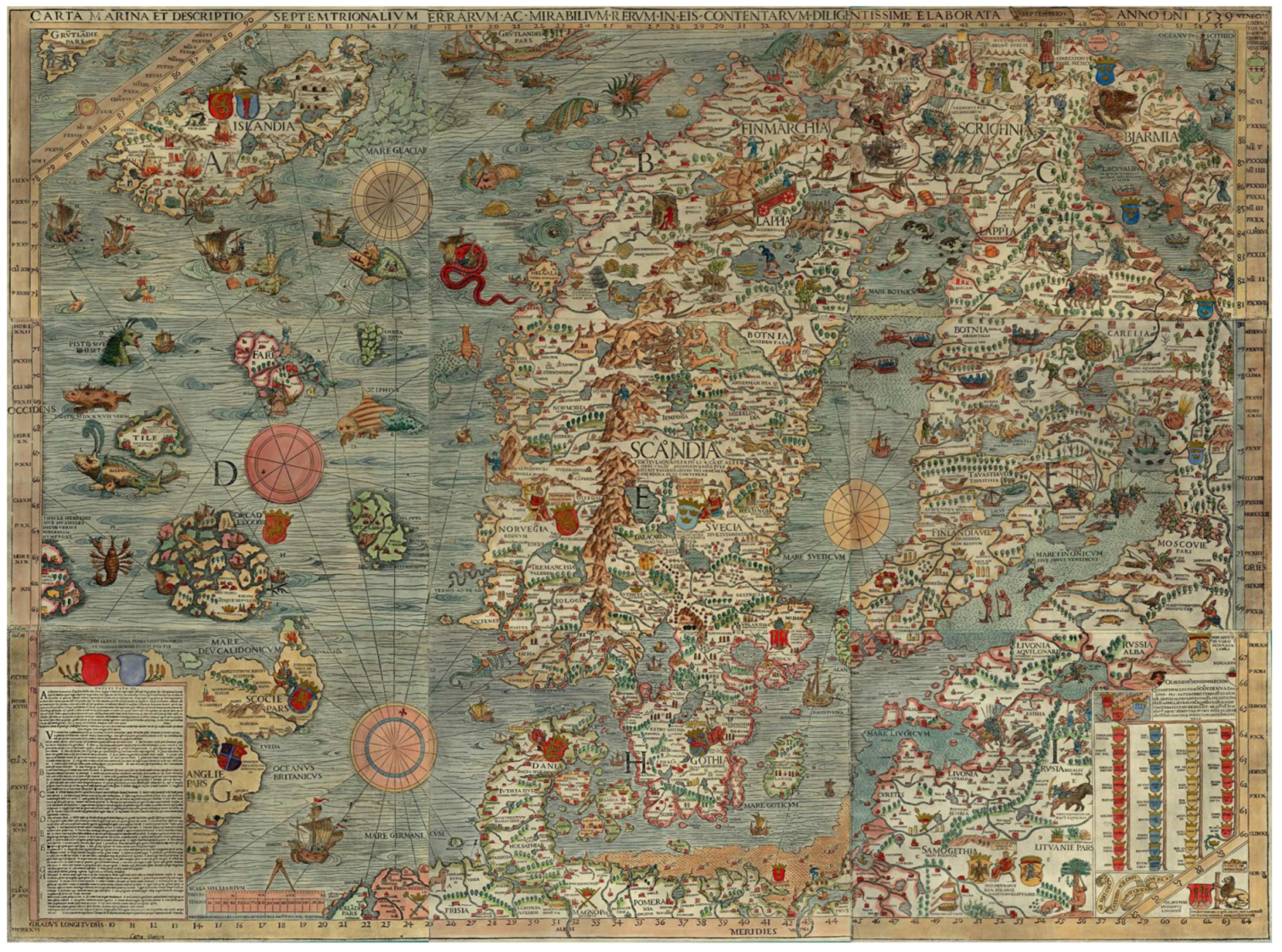

A concrete and emblematic example in which the proposed reflections can be seen is the one described by Carta Marina et descriptio septemtrionalium terrarum ac mirabilium rerum in eis contentarum, diligentissime elaborata anno1539 Venetian liberalitate Reverendissimi Domini Ieronimi Quirini, written in 1539 and published in Venice by Olao Magno (1490–1557) (

Figure 1); in this geographic map [

1], well-known to theme researchers, it is possible to find a fairly reliable configuration of northern Europe, from southern Greenland to the Baltic coasts of Russia, which at that time were little known in southern Europe. According to the author [

2], such an exploration has to lead the traveler towards a realistic perception with regard to the representations of the mainland, while immersing himself in the cold seas of the Nordic countries, assumes the characteristics of the imaginary world. By looking at the geographic map in detail, the description of the mainland is likely to be reliable in representative terms: there are natural elements eligible under the geographical description including mountain ranges, lakes, rivers, trees and fauna encountered most likely, during travels; other peculiar details relate to coats of arms and nomenclatures that in some cases help to add informations about well-known cities, while others favor the political and social power of the place. But the real wonder is entrusted into story of the sea [

3]: all the species that populate the vast expanses of the sea have a fanciful return far from the canonical representations of animals, but are probably the result of an improper and skillfully re-elaborated representation of the species known during the journeys on land and by sea. The fear of travelling to unknown and difficult places, especially during long itineraries in impervious and adverse waters, has created an instinct to recreate images that express the fear of negative emotions; we observe therefore singular animals with a horrible appearance, square headed beasts with spined skinned bodies, sharp claws and threatening teeth. The power of imagination, blended with the sensations created by the fear of the seas and the unknown, is the source of this imaginary and singular world.

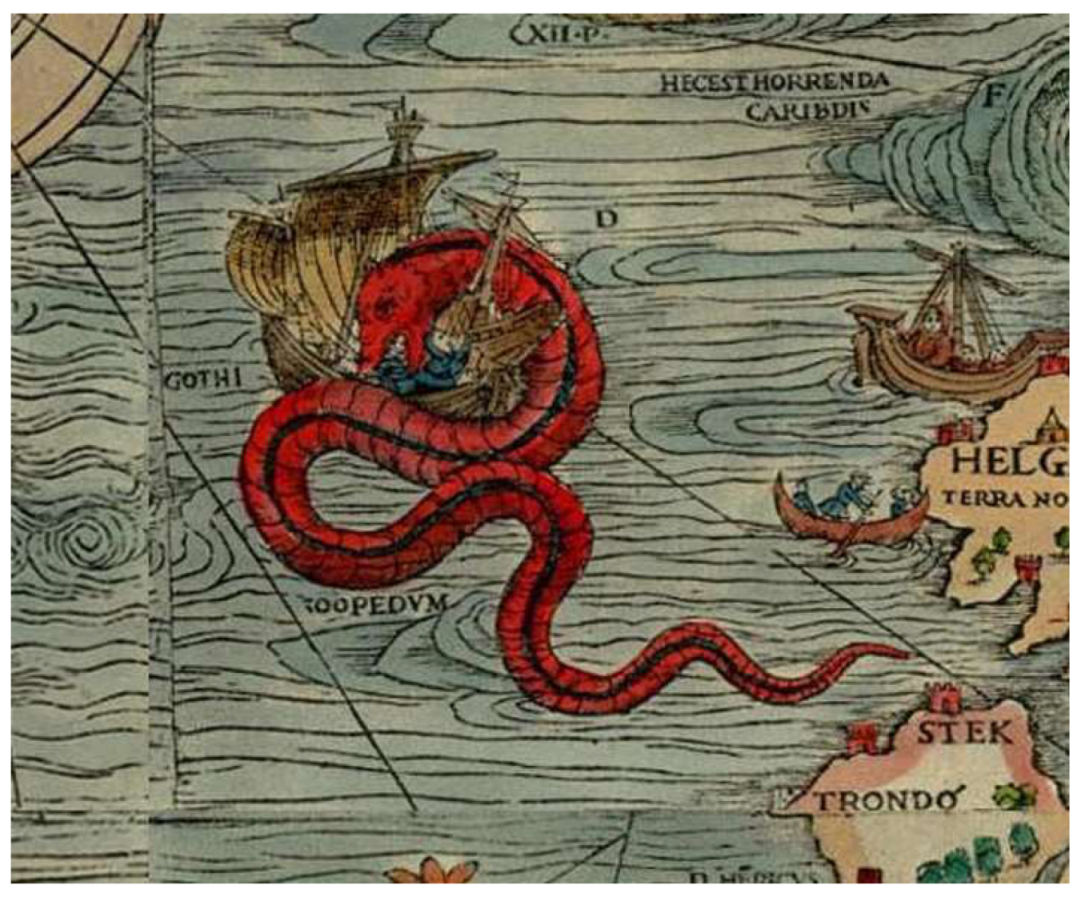

Olao Magno’s Carta Marina can therefore be read in two ways: from land-side or from sea-side. Along the dry land itineray, there are rather common and well-known environmental conditions and species of animals probably spotted during numerous trips to the North. Immersed in cold waters represented by Magno, we encounter disturbing animal species loaded with suggestions and fantasy. In many other maps along with that of Magno, were featured sea monsters, including dragons, which indicated the danger of certain places and waters not to be navigated—probably because they were not yet known at that time—but considering the representative meticulosness and the level of detail in the nomenclature, most probably they were considered existing creatures in that period. On the map, there are curious navigation details that are a symbol of fears due to the lack of knowledge.

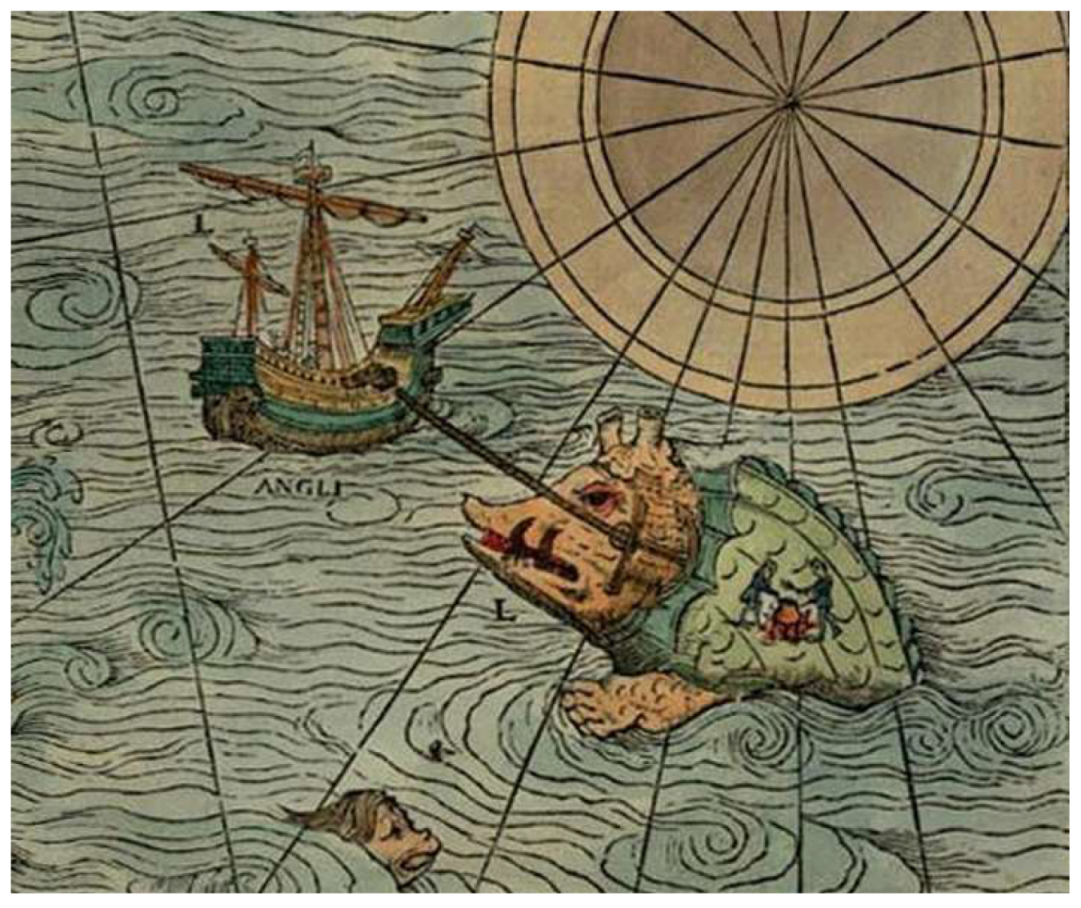

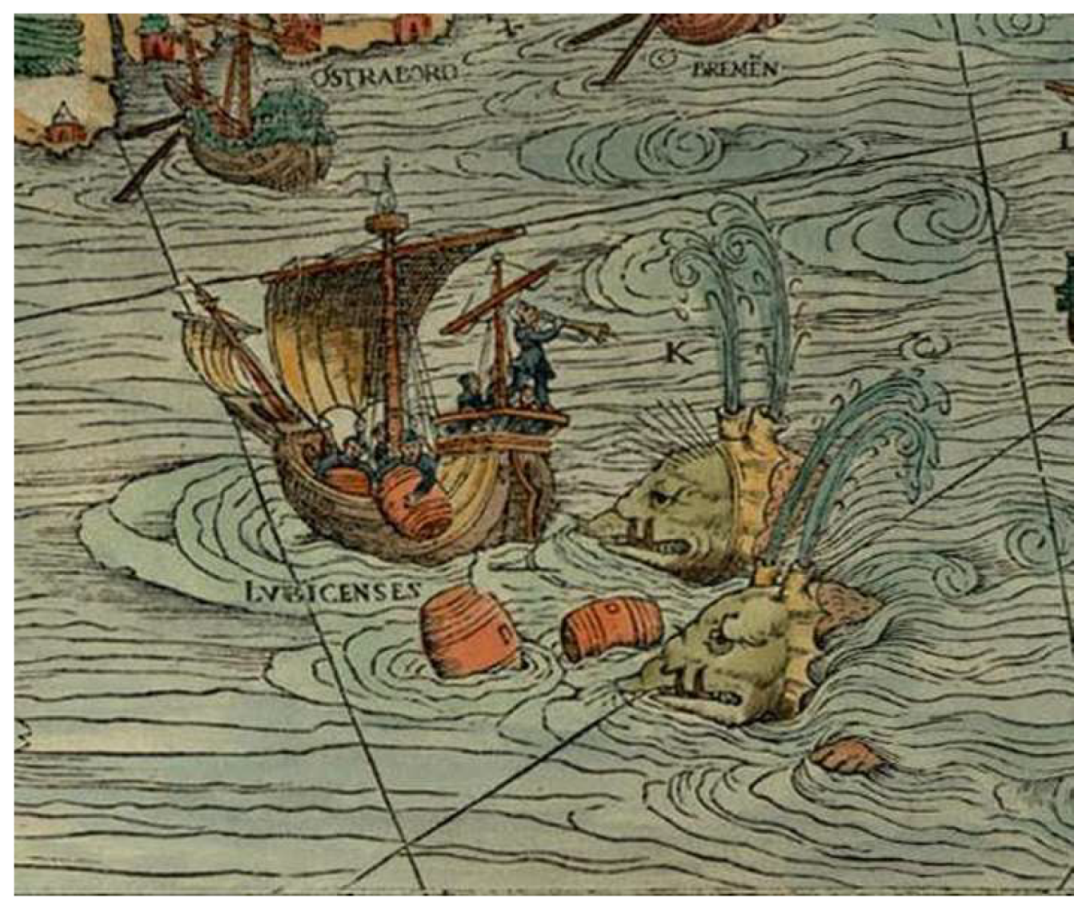

There are sailors cooking food on the back of a whale on whose body they moored the anchor of the ship (

Figure 2), rather than a sailor who plays a trumpet so to get rid of some sea monsters buried by barrels (

Figure 3); it still appears a red dragon to destroy a ship that probably ventured into dangerous places (

Figure 4) and the inevitable Leviathan, a creature dreaded and recognized since the ancient times (

Figure 5). Again, several other monstrous sea animals populate the Magnificent Seas, including the owl and a rhinoceros-similar creature whose purpose was to destroy the ships from the hull to make them sink (

Figure 6). In other words, the dangers of navigating the seas are mainly told by the cartographies of that time of partial exploration and the messages left by navigators in the decorative cartographic (

Figure 7) apparatus catched the attention and at the same time the curiosity of the adventurers who, in the years to come, deny such psychological artifact by transforming knowledge into a conscious representation.

The extraordinary nature of this type of maps, of which the

Carta Marina represents one of the best examples, witnesses the wisdom and the brave experience of explorers of the uncharted places and constitutes a historical and cultural heritage to spread, safeguard and communicate. By carefully looking at these elaborate maps, one is amazed at the subtle detail, descriptive precision and harmonious proportions set between the details and the overall design. The consideration that gives an even greater cultural value to these cartographic productions is that such elaborations are the result of the tempting experience of the navigators and travelers of that time, who, supported by no astronomical determination, let experience and sensitivity be the result of their individual production. These maps, therefore, have become “a corpus of strange things that fascinates us and frightens us, which has come to us through the resonance case made up of mythologies of all time and place, as well as an immense patrimony of testimonies, often lacking adequate useful documentation of reference to deepen the understanding of the phenomena” [

4].

The study of such a large iconographic context allowed the map to be considered as a visual text and the analysis conducted concerned the semantic fragmentation of the graphical apparatus fitted with the map generally understood as a testimony of the places that had changed over time and in history. Therefore, the duplicate reading of the meanings (objective context) on the one hand and the signifiers (hidden context) on the other, let us understand the implicit, and often more interesting, information about the communication of the intentions represented.

To give a context to the mapping of the Abruzzo region, and by distinguishing the purely technical and functional geographic content from the illustrative apparatus which amplifies through the images the meanings that the cartography fails to communicate, the selected maps are reviewed; it is also noted that only some generic iconographies of Abruzzo are presented, selected to illustrate the fundamental stages of the graphic and semantic evolution of places, and since they give the opportunity to know the developments of the territory from the middle of 1550, in particular of the circumstances narrated through the languages and aesthetics utilized. Considering therefore only a limited selection (also applied to the pictures for editorial purposes) of the numerous Abruzzi cartographies produced over the course of time, the focus aims to retrace all the graphic characterizations and the languages typical of the representations used over time to tell a territory so singular and articulated as the Abruzzo. In order to make a critical comparison of the iconographic apparatus characterizing the chosen and ranked cartographs in chronological order, a graphic matrix has been created from the starting maps on the y-axis while the x-axis was selected for the structuring themes and subsequently listed: “coat of arms”, “symbol”, “measure”, “nature”, “navigator”. It all has been theorized so to break down the total image into individual fragments, each bearing their own message; the operation involved shifting the attention to the hidden meanings in historic maps that provide significant testimony to the political power of the time, rather than commending homage, state of knowledge of the period, memory of events, and emblems and real or mythological symbols used to stop the exploratory phases of maritime itineraries in the event of the representation of the ships or to warn of the dangers of the unknown and unkown sea trails in the case of sea monsters.

In particular, the following maps are taken into account:

Aprutii Ulterioris Descriptio, Antwerp (1590) by Abramo Ortelio;

Abruzzo Ultra et Citra, Bologna (1620) by Giovanni Antonio Magini;

Abruzzo Citra et Ultra, Amsterdam (1645) by Joan Bleau;

Abruzzo Citra et Ultra, Rome (1714) by Domenico De Rossi and

Abruzzo Ulteriore e Citeriore, printed by Antonio Zatta, Venice (1783) by Antonio Rizzi Zannoni (all the ancient cartographs mentioned are kept and cataloged at the State Archives of Pescara) (

Figure 8).

By analyzing the maps from the point of view of the iconographic notion rather than cartographic and functional ones, we highlight the coded messages that give the possibility to have a greater understanding of the maps often relegated to a sort of documentary heritage that is misinterpreted and difficult to understand.

3. The Reading of the Unconventional Codes of the Maps of Abruzzo

By visually navigating the maps selected for this search, one can trace a heritage of excellence, both graphic and of informations, which is considered a cultural asset to be retained and handed down, with a strong focus on enhancing and scattering the underlying messages. Looking at the extensive paper and documentary heritage, it is understood that not only the strictly physical and natural evolutions have affected the first cartographic inventors, but also the practical anthropological impact, the major cause of sudden changes in the layout of the places, along with the psychological one, has been long investigated and told. In the research that has been carried out, the aspect of greater interest to be studied refers to the study, collection, valorisation, preservation and dissemination of the rich unconventional illustrative patrimony of the Abruzzo region cartographies described in terms of the iconographic apparatus in support of the technical language.

The accurate investigation of the heritage of the ancient cartography becomes then structured so to understand the cultural changes of the subject and to have an opening field related to the graphic evolution of the systems of representation of the territory; an important aspect lies on one hand in the alternative reading of the history and progress of peoples, on the other hand, the continuing need to leave a graphic witness to the territorial events and the long-lasting discoveries made over the years, constantly experimenting with the direct relationship with the space.

By focusing and caring for the critical reading of the past cartography, the most interesting aspect is the continuous need to synthesize the places experienced through conventions and graphic encodings typical of the maps and the elements reported on the maps—referring both to technical and illustrative languages—there is an constant need to orient oneself through territories that have uncertain, sometimes critical, configurations and boundaries, experimenting with paths and localizations linked to direct and imaginative experiences within a space each time surrounded by historical and travelling needs.

During the analysis of the maps of the Abruzzo region through the selected keywords—“coat of arms”, “symbol”, “measurement”, “nature”, “navigator”—that refer to the unconventional cartographic representation, a reasoned interpretation of the meaning of every single symbolic representation is proposed. To implement a breaking down process of graphics and significance, means to have the possibility to understand, by chosen parts, the sense that broaden the technical concepts related to the knowledge of the territory. The necessary premise before discussing the subject is to refer to the maps of Abruzzi here considered: that iconographic apparatus does not merely fulfill the aesthetic and practical function (nomenclatures and dates) but collects and specifies a series of informations necessary to understand what cannot be explained by a purely technical map. By absorbing graphic heritage from the nautical and land cartography typical of the 13th to the 16th centuries, which is perfected over the years and meets increasingly sophisticated navigation requirements, the maps selected for research are the result of appropriate scientific, technical and artistic surveys of the time, which tend to be a symbolic representation of the territory of Abruzzo but also it is rational from a geographical point of view.

Regarding the first theme that refers to the “coats of arms” and the emblems of power in the chosen papers, it is immediately understood how these elaborate pieces always have new geographic discoveries enriched by graphic licenses that enhance the commission as well as the knowledge. To better understand the meaning of the coat-of-arms and icons of the map scrolls—particularly those presented—it is necessary to read the paper as a text that has its own language and, consequently, a social interpretation often filtered by geopolitical control; in other words, on one hand, the map can be read through consolidated codes so to interpret sociologically and hierarchically between power and knowledge, and as an act of control of public and private places and not trivially as a document embossed with decorative embellishments on the other.

The theme of the “symbols”, introduced already in the first lines of the text, refers instead to all the signs that want lead the reader to meanings seemingly hidden between the lines with respect to the explicit communication of the information on the territory. According to different interpretations of the theme by the scholars, symbols within the maps want to communicate different messages; on one hand they serve to give precise indications on a particular situation—the dangers of the seas like sea creatures in the case of not yet navigated waters or, on the contrary, the safe seas witnessed by vessels navigating—and on the other, they want to confuse substantive notions of the territory with graphic allegories to respond to a precise will to exercise power or even to fill empty spaces for purely graphical needs. Sea monsters and curious creatures that inhabit the seas and sometimes the lands in cartography of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries have a very different meaning from the representations present in the medieval beasts who, by the same nature, relied on a biblical and religious language; since 1500 these symbologies move from a metaphorical level to an allegorical and interpretative one, to disappear almost completely in the later centuries when the scientific knowledge of the lands and seas is supported by the first important scientific instruments of land survey that rubbed out any doubt about the knowledge and uncertainty of the known places.

The representations that explain the concept of “measure” within the maps considered reflect the need for cartographers to apply pseudo-mathematical notions to the elaborates, indicated by readily legible but not supported by precise geometric concepts since they still have no chance to be compared with the instruments suitable for the purpose. The recurring element in the maps considered in terms of the measure is the graphic scale: this convention, already present in the first cartographic representations of ancient times, is represented by a segment divided into equally long portions each referring to a unit previously established. This graphic convention is widely used since it offers the possibility of establishing, by a simple comparison with the chosen unit of measurement, the length of a map section, unlike the numeric scale that requires a precise measurement resulting from the ratio between the unit and the number to which one has to multiply the measure taken on paper to actually obtain the accurate measurement. Often the scales are embellished with rudimentary drawing tools or frames that give a visual appeal and emphasize the relevance of the other elements in the maps.

A similar discussion concerns the first traces of “navigators” within the maps of the time; there are always well-kept inscriptions referring to the cardinal points (south, north, east and west) and suggesting the main directions within one can move and more importantly orient oneself. In the cartographies of the XV and XVI century the Latin expressions prevail, and in some specific cases the cartographers are granted poetic licenses related to the etymology of the terms; a specific example concerns the word “south” which is a derivation from the Latin term meridiem meaning “noon” and often appears as an indication on the maps.

With respect to the theme of the representation of “nature” and the complex relationship between this and the action of man, in the Abruzzo’s maps taken into consideration—but generally in most contemporary maps—it leaves great room to the representation of natural elements; the consideration to be given to naturalistic representation is that they draw on the visual and cultural heritage of cartographers and travelers who have experienced the places described, trying to capture information as close as possible to reality in terms of the description of the territory but at the same time that are structured upon complex symbolic references as well as on direct observations. This results in a subjective representation which is conditioned by the inner perception that makes the comparison between maps more problematic. Such naturalistic representations adhere to the strictly cartographic narrative, enriching and enhancing the elaborates graphically, without interfering with the ultimate goal of the landscape that must meet specific cognitive needs (

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

The cartographic results of the period examined, with particular attention to the Abruzzo region and with the proposed insights, constitute a rich intellectual heritage that offers the possibility to understand, through analyzing the semantics of the map’s space and by breaking down the meanings represented from the thematic point of view, the social and political situation of that time, offering ever new ideas to complete and verify through the later ages the dots that structure the historical, cultural and social evolution.

4. Conclusions and Future Developments

The objective of the research, still open and by its nature constantly evolving, concerned the study of some codes relating to the historical languages of the representation of the complexity of the territory, by the unconventional reading of the maps of the land of Abruzzo; in particular, the study of the ancient cartography of the Abruzzo region has allowed us to acquire substantial informations on the methodologies used to give structure to informations for the purposes of representation of the territory on one hand, and through graphical messages calling for maps to be used for different purposes from those specifically technical on the other. The analysis carried out about the historical mapping document has led the same to be considered as the medium capable of breaking down and decoding the geographical and illustrative territorial elements, the representative factors that have changed over time and those apparently concealed by deeper meanings and signifiers and not immediately visible, but that gives the opportunity to understand the relationship between man and territory and between cultural context and sensory experimentation.

In conclusion, the most interesting aspect that justifies an ancient reading through hidden and implicit codes is the acknowledgment of the high value of every single work that has over time carried intriguing messages of historical and cultural contexts, often unfamiliar, in which it was formed. A reading of the exceptional iconographic heritage, such as historical cartography, generates renewed attention and an open interest in the cultural question relating to the use, conservation and consequent enhancement of the historical-representative heritage and the semantic-graphical codes handed down from the past and yet valid but transformed nowadays in coherence with the new languages of communication in the field of representation of the territory.