Abstract

Colour, imagination, inspiration, amazement. These four words very fittingly describe the work of the Viennese artist/architect Friedrich Stowasser, better known as Hundertwasser (meaning hundred water), a master of organic thinking who between 1928 and 2000 worked and lived in Vienna, Venice and New Zealand. He uses eye-catching images to convey his ideas, forcefully expressive chromatic forms and patterns that betray a strong link with a re-interpreted geometric structure. This contribution, inspired by Hundertwasser’s works, intends to study the unique relationship between creativity, imagination and architecture based on sociological, cultural and psychological principles.

1. Introduction

This extremely creative Austrian artist, endowed with great intellectual courage, succeeded in honing his many artistic skills in various mediums: painting, architecture and drawing. For many years he explored the world by living on an atelier-boat, visiting many countries across all the five continents; his travels led him to tackle ecological problems and, as a result, become a forefather of the current environmental movement. Colour plays a leading role in all his works, probably because it jumps out at you before you see all the other elements in an architectural project: form, structure, geometry, proportions and size.

The different and often conflicting chromatic effects of his ideas and creative drawings transmit great energy and dynamism. The expressive freedom he used in several fields is the cornerstone of his artistic development: stamps reproducing different parts of the world, numerous posters, ceramic objects, many important architectural works (Figure 1) and publications, including the famous Brockhause encyclopaedia (1989). When the twenty-four books that make up the encyclopaedia are joined together, either open or closed, they create a single, large-scale image.

Figure 1.

Hundertwasser’s stamps.

2. The Colour of the Project

Although Hundertwasser has been awarded numerous international prizes, he still remains a relative unknown in the artistic and architectural milieu. This contribution uses the artist’s works to study his unique creative system since it can still be a valid source of inspiration. “Hundertwasser is a rare example of optimism, hope, trust in life and the power of creativity” [1]. He began his career as a painter, developing a technique known as “transautomatism”, an instinctive way of painting using the subconscious, a sort of primordial trance generating abstract paintings dripping with colour and decorations. His art is a mix of ecology and dreams, emotions and imagination; the heart and soul of his artistic career is the varied, coloured, naturalness of life, an element that made him the forefather of the current environmental movement [2] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hudertwasser’s images.

At the time some of Hundertwasser’s ecological ideas and projects were inspired by the severe environmental instability caused by the breakdown in biological cycles forcefully implemented by society’s growth model. One of the fiercest debates revolved around the removal of the undesirable elements produced by society, i.e., excrements, waste and cadavers. Hundertwasser proposed several solutions to these problems, including a humus toilet and a project for the recycling of the dead. Unlike most contemporary environmental movements he thought that creativity had to necessarily play a key role in ecology.

The artist-architect studied community problems, focusing in particular on the social environment. He was convinced that: “when we dream alone, it is only a dream, but when many dream together it is the beginning of a new reality” and “... if people are pessimists in our society, the artist has an obligation to the society he lives in to warn and to look for solutions” [3]. Hundertwasser’s images include many round forms, circles and spirals. The latter were probably inspired by other sources: the paintings of the schizophrenic patients he visited at the University of Medicine in Vienna, or the works by Austrian Secessionists, in particular Gustav Klimt [1] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Hundertwasser’s spiral images.

While Hundertwasser’s style is reminiscent of the works by Egon Schiele and Paul Klee, he introduces something new by using artistic expression as a way to express his enthusiasm for nature and its main elements such as water, vegetation and trees. His pictorial experiments often focus on recurrent themes, including representations of water, to which the artists assigns a very intense meaning. In fact, he often portrays rain in his canvases (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hundertwasser’s images with the rain.

His identity, imbued with diversity and creativity, is armed by a desire to always leave a personal touch. He is fiercely opposed to uniformity and trends: “... my painting is completely different because it is a vegetative painting ... everything begins so unpretentiously ... it grows quite slowly and simply ... colours in succession can create the effect of visual music ... I consider colour a sacred gift ... while I paint I feel I am in a dream. Once the dream is over I do not recall what I dreamt. But the painting remains. The painting is the fruit of the dream”. Or “I wish they [dreams] would be considered as a way to spark a creative world. I would like them to be an example. Painting is only an exercise to prepare for this goal—a sort of prayer [3].

Hundertwasser’s creativity was inspired by freedom of thought, independence, courage, the will to take risks, a strong spirit of adventure, and a desire to experiment coupled with great faith in the creative impulse. He considered his way of thinking was more important than the teachings of tradition. In fact he maintained that nothing is ever fashioned out of nothing and that there must be space for renewal in the debate between tradition and transformation. He experimented with many materials and techniques, working at length in the field of graphics; to reach as many people as possible he always printed additional copies of edition so that they were cheaper.

He loved diversity and detested duplicates; he wanted each copy to be original. In fact, using a complicated process of chromatic combinations he succeeded in creating 10,000 copies from the same serigraphic matrix, changing the colour tones in each one. His work demonstrates how integration is always important during experiments performed as research since integration makes it possible to compare and find new relations that allow humanity to take one small step forward on the path of knowledge. “I feel we’ve come to a turning point. It’s like the vault of a dome, the segments of a bulbous tower. Our starting points are different, I’m currently in the phase in which all the extremities converge. I’ve drawn stamps and worked as a sailor, architect, environmentalist, painter, etc.; all these activities now merge and flow into a single point. This makes me happy and justifies my work” [3].

3. Architectural Works

In the sixties, when Hundertwasser was thirty, he found himself working in western countries where the confusion generated by the Second World War had an undercurrent of deep unrest, anxiety and mistrust. As the primary implementer of social action the State had begun to loose authority; at the same time there was a simultaneous increase in the problematic dynamics of consumerism and technological innovation.

It was then that a new relationship between art and life began to develop together with a cultural debate regarding the potential of artistic languages and the art system, a provocation by elitist culture vis-à-vis mass culture. As a result, new artistic movements slowly emerged. “His genius explodes in architecture, cloaking it in history. Buildings “live” in a total, organic design in which habitat, land-art and territory conspire together in a sublime, unique and unrepeatable synthesis” [2].

Hundertwasser saw himself as a “doctor of architecture”, a profession he invented to transform and embellish existing buildings that he believed lacked personality and life.

He rejected the idea of standard windows on the façade of a building and instead proposed different window types. He designed buildings in which the tenants could modify the part of the façade around their windows within arm’s reach; this was intended to stimulate an individual’s spontaneous creativity, in both the communal and private parts of the block. He also criticised standardised industrial colours and intervened in production processes by personally creating his own colours.

Hundertwasser believed that rationalist architecture was at the root of urban disharmony and the problems it created. He proposed projects that would improve and beautify the world, “his actions, provocations and battles express aggressiveness, but it was a positive aggressiveness, one he needed to develop his creative process. His goal has always been to embellish and enhance people’s lives” [1].

He searched for harmony between man and nature and proposed combining them with beauty. He theorised that together these factors could bring happiness to the individual and society as a whole. Part of his premise was that there is always a link between architecture and our mental state. An emotional impact of colour. Hundertwasser used to say: “... of course, one should paint, but above all it involves lifestyle. It’s one way of looking at the world, of acknowledging the beauty around us and helping to contribute to it”. We should study “where” human activities are performed; it’s important to examine the relationship between space, individuals, and what they do, so that these three things influence each other.

It’s crucial to understand the effects and consequences that this interaction has on architecture. Surroundings, context and the physical properties of space influence and inspire the development of experiences and define their quality. Although Hundertwasser loved nature he did not withdraw from civilisation in search of his own, personal, idealised paradise, as so many artists have done throughout the centuries. His love of the environment created profound, inner respect and a refined ecological conscience; his work as the doctor of architecture was his very personal contribution to the enhancement of the world.

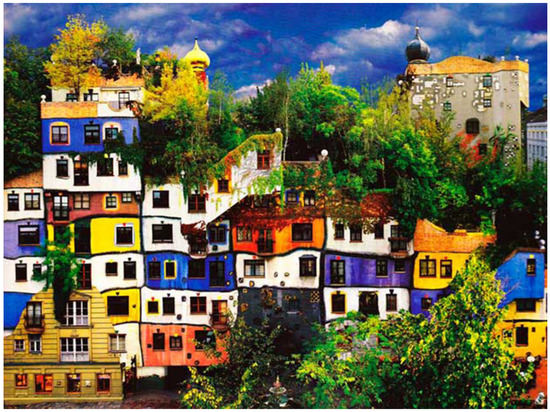

The Hundertwasserhaus, an amazing public housing complex, is one of the artist’s most important architectural works. Others include the Hundertwasser Museum in Vienna, the Spiral Forest in Darmstadt (Germany), the Incinerator in Osaka (Japan) and the Church of St. Barbara in Stiria-Graz (Austria). None of these works conform to the academic architectural rules that were in vogue during that period, instead they look more like interpreted dreams. Together with the architects Josef Krawina and Peter Pelikan, responsible for the final project, in 1985 he built the Hundertwasserhaus in the third municipal district of Vienna. The façades of this complex, in the Landstraße neighbourhood, east of the city centre, are painted and decorated with strong, bright colours (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Façade of the Hundertwasserhaus.

When Hundertwasser designed fifty apartments for less affluent citizens he used soft lines without any sharp corners to convey cheer and happiness. The colour green prevails in every apartment, especially on the terraces where hanging gardens are a clear reference to one of the artist’s key concepts: everything that is horizontal belongs to natural reality, everything that rises skywards is manmade.

Even most of the materials used to build the apartment block, especially the decorations, are recycled. In fact, the architect always took great care over these basic features. The Viennese press was initially very critical; they used several terms to describe it, including “parrot house” or museum of the grotesque”. Instead many inhabitants were enthusiastic, especially because they themselves could create mosaics and patterns in both their own home and communal spaces. The unique characteristic of Hundertwasser’s projects was that he allowed residents to use their imagination. Even if they were renting from the municipality they could personally decorate their homes based on their own taste.

Their creativity also applied to small spaces, such as bathrooms and toilets, completely covered in coloured tiles and decorated with patterns and painted fountains, also in strong, gaudy colours (Figure 6). The architect wanted to turn the area into an oasis inside the city by placing plants and foliage on the balconies and terraces of the Hundertwasserhaus: “An unusual house that doesn’t correspond to the usual clichés and norms of academic architecture; a house designed and drawn by a painter ... a journey in a land where nature and man meet in creation ... a painter’s dream of housing, a beautiful building in which man is free and where his dream becomes reality [3].

Figure 6.

Interiors of the Hundertwasserhaus.

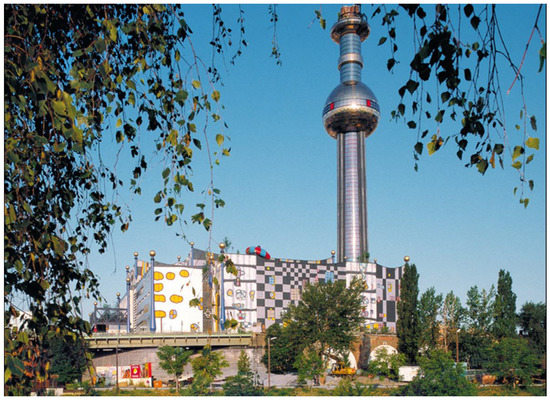

Another very interesting project was the incinerator (Incineration Plant Osaka) built by the Austrian architect on an island in the Bay of Osaka in Japan not far from Universal Studios. Every day this incinerator burns 900 tons of waste. It was an intelligent environmental conservation project that also considered the question of perception. In fact, the extravagant building with its round forms and coloured structures looks like an amusement park (Figure 7). These very unique, unusual and different places share a common objective: to embellish and enhance the world. This characteristic has turned them into tourist attractions.

Figure 7.

Incinerator in Japan.

4. The Built Environment and the Human Mind

“Spaces in public housing, especially the interior, are often considered as indistinguishable, not linked either to the activities performed in them, or the people who live there. This theoretical design approach has generated “foreign” spaces, difficult to live in and expensive to maintain due to environmental discomfort, scant personal involvement, and dissatisfaction with public services” [4]. Spaces can spark different moods in people; feelings of contentment that channel energy towards creativity and optimism. This is achieved, for example, thanks to the brightly coloured designs on Hundertwasser’s architectural works which, by appealing to a person’s senses, help to ensure psycho-physical balance.

On the contrary, ugly architecture with dull colours can dampen the mood, creativity and imagination of onlookers and users. “The environment conveys messages that are intuitively understood, even if they cannot always be rationalised. Space can spark feelings of wellbeing or discomfort; it can stimulate, depress or send messages of self-esteem, social status, safety and identity; it acts as a catalyst in personal and social dynamics” [4]. Hundertwasser’s work drew people’s attention to the problem of the liveability of community spaces and the need to make them more open towards the city and social interaction. He also emphasised how important it was for architects and designers to focus on this delicate task. The United States of America is one of the countries in the forefront of neuro-architectural research; its authoritative research agency, the Academy of Neurosciences for Architecture (ANFA) in San Diego, studies how the nervous system reacts to the built environment.

The topic is high priority even in Italy, especially in recent years; in fact architects and neuroscientists often meet to discuss how to design human-scale spaces [5].

Architecture artificially shapes the external reality we live in, but it also reveals our inner world since it is the link between our conscience and the world. Numerous multidisciplinary studies focus on trying to understand not only what effect the layout of our environment has on the human mind, but also how to help architects design more functional spaces. “The results of recent studies in the field of neurosciences provide us with a better understanding of how the built environment influences our health and well-being, how we act and think in our work and life environments, and what we feel when we live in them” [6].

These studies also focus on improved spatial distribution in physical and mental health structures where a merger between architectural knowledge and neuroscience can be usefully applied. Even the use and choice of special colour combinations, especially when people are hospitalised, can help improve their mood, channelling their energy towards inventiveness and confidence and distracting them from pain and distress. In fact, courageous chromatic solutions stimulate the sense of sight and can help to establish psycho-physical balance and improvement in a sick person. Given the sensibility Hundertwasser demonstrated during his life’s work he can be considered a forefather even in this field.

5. Proposal

As mentioned earlier, in his manifesto Hundertwasser defines himself as a “doctor of architecture” because he believed it is possible to enhance existing buildings, make them more uplifting and, above all, reinstate their social and cultural identity. A meticulous review of the artist’s work inspired us to study several buildings in Rome which we thought were in need of enhancement, especially their façades. We used drawing as our method and chose buildings with kindergartens; we then proceeded to execute drawings reminiscent of the artist’s personality, using his chromatic effects and lines. Like doctors of architecture, our attempt focused on drafting several enhancement options.

We opted for buildings with kindergartens because many of these structures are prefabricated, both in the city centre and the suburbs. Their interiors are normally aesthetically and functionally well designed because this space is the one children use the most; it has to be comfortable, friendly, coloured and inspirational at the same time; instead, the exterior are usually unexciting. Our study produced ideas and images that can help identify possible ways in which to decorate the sometimes nondescript buildings and enhance them by adding features that cheer up onlookers and convey the identity of the buildings.

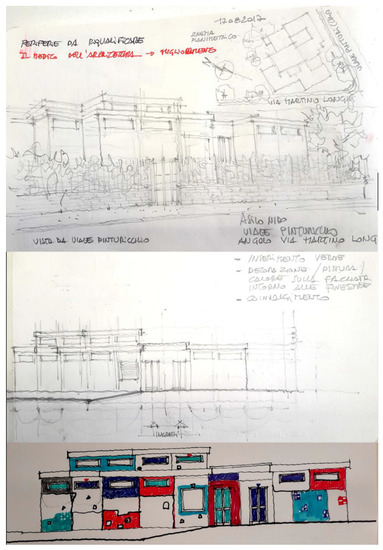

One of the most interesting aspects of Hundertwasser’s embellishment process is to give the user of the building free rein to decide on the work to be done. By involving and increasing manual labour while taking care of the place where one works, studies or lives not only produces a positive fallout in terms of personal change and solicitation, it also influences one’s psychic mood. The kindergarten in Viale Pinturicchio in the Flaminio district of Rome was the chosen venue for our experiment. It is a squarish, one storey prefab building in a regular lot next to Piazza Mancini, a square with a busy bus terminal (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The Pinturicchio Kindergarten.

The parallelepiped elements joined to form the building are surrounded by a garden with games, slides and swings. The fence around the garden, covered in climbing ivy, acts as a screen to stop people from looking in. We established several guidelines and made useful suggestions regarding changes to the exterior of the building (Figure 9). The suggestions include: personalising the space around the windows with patterns and colours; inserting lots of plants wherever possible; adding suitable decorative elements.

Figure 9.

Graphic indications.

6. Conclusions

The goal is to focus on certain characteristic architectural types present in Rome and propose their embellishment based on a special but simple and economically inexpensive enhancement process. The proposal to boost the aesthetics of buildings can beneficially influence the community given the positive effects that pleasing, congenial surroundings can have on citizens, especially in a big city like Rome.

Our drawings have enabled us to not only propose several project options in a non-invasive manner, but also convey the objective using ideas and images. We believe that Hundertwasser would probably agree that, hopefully, our proposed enhancement options be just a first step towards widespread awareness of the problem and ensuing upgrade.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Villela, G. La creatività e lo sviluppo del sé. Riflessioni a partire dalla vita e l’opera di Hundertwasser. In Riunione Scientifica A.I.PSI; 11 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mostra. La Raccolta dei Sogni. Hundertwasser; Art Forum Wurth: Capena, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rand, H. Hundertwasser; Taschen: Colonia, Germay, 2009; ISBN 3822829349. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, E. Introduction. In Lo Spazio Terapeutico. Un Metodo per il Progetto di Umanizzazione Degli Spazi Ospedalieri; Bellini, E., Bocci, P., Fossati, R., Spinelli, F., Eds.; Alinea Editrice: Firenze, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Seminar “Architettura e Neuroscienze. Tecnologie e strumenti per un nuovo paradigma del progetto”. Research Doctorate in “Progetto e Tecnologie per la Valorizzazione dei Beni Culturali”. Politecnico di Milano.

- Cit. Architect David Allison, director of Clemon’s graduate programme in architecture + health.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).