1. Introduction

“Educating and telling” in the experience here proposed can be reinterpreted with the expression “Educating to telling”.

This could means telling, by the way of drawings and of Photography, some mnemonic images of well-known spaces (like for example the village, the streets, the daily paths) or of an usual building (for example the school): spaces and buildings that in few seconds were destroyed or transfigured by a catastrophic event as an earthquake.

The storyteller’s point of view, in this experience, is really special: it’s that of children of elementary school of Gualdo (Macerata, Italia) (

Figure 1). They were engaged in an assisted laboratory, to think about their sense of loss and about their perception, memory, emotion.

2. The Object of Study

The project I would like to propose in this International and Interdisciplinary Conference is part of an institutional activity of the University of Brescia, that I coordinated as the Rector’s Delegate for Buildings and Properties [

1].

The triggering events were the earthquakes that struck central Italy on August and October of 2016. They destroyed overall villages and they damaged many public buildings, included school buildings.

All the italian community was very shocked and would like to help the people in trouble.

After the earthquakes, the “Giornale di Brescia” (a very popular newspaper of the district of Brescia) launched a public fundraiser for the reconstruction of the school of Gualdo (Macerata), a little village in the Marche region severely damaged.

Gualdo wasn’t be entirely destroyed by the earthquakes (like it happened to other villages in the area) but it was strictly damaged: anyway, the six churches totally destroyed and the historical downtown completely impassable demonstrate the seriousness of the situation.

The school building of the XXI century, for example, was damaged and it was at once classified unusable by the specialists (

Figure 2).

The ministerial team for Education (MIUR) immediately confirmed the importance of the school for all the surrounding area, because here there’re kindergarten, elementary school, middle school: consequently this building (and not some of them in the other villages) had to be rebuilt.

Consequently the Department of Civil, Environmental, Architectural Engineering and Mathematics (D.I.C.A.T.A.M.) of the University of Brescia decided to arrange the architectural project of the new building and to donate it to the community of Gualdo, coordinating and working with the Associazione NON LASCIAMOLI SOLI, born for this special issue.

The name of the in-progress procedure is “Scuola a Gualdo #Nonlasciamolisoli” (“School in Gualdo #Let’s not leave them alone”).

3. References and Landmarks of the Idea

The idea of involving the direct users of the building and of realizing a project only after proposing to the school population a Laboratory project activity is coherent with the orientation of the European Landscape Convention (Firenze, Italia, 2000; it become law in Italy on 1 September 2006) on the theme of recognizing the quality of places where citizens live.

The first survey at Gualdo highlighted two different but important aspects:

4. Method Used

From these reflections, an idea was born: to engage the youngsters in an assisted laboratory, as a simplified version of “Participated Planning Laboratories” commonly used in public space design.

The involvement of the population is provided by the European Landscape Convention. It promotes informed participation in choices and increases awareness and education for a landscape culture [

2].

If we speak to the children we achieve the best result in order to education of tomorrow’s citizens.

The Laboratory called “La scuola da cui guarderemo il mondo” (“The school from which we’ll look at the world”) was designed and coordinated by professor Barbara Badiani, member of D.I.C.A.T.A.M., University of Brescia.

It was structured according to three different paths, depending on the grade level: kindergarten, elementary school, middle school.

The goal was to make students think about the new building as a place from which to look at the world with renewed confidence. What features should be saved from the previous building? What would they like to find in the new setting?

We also proposed to think about the space and the paths between each house and the building: which views of the school building or of the surrounding have they saved in their heads? Witch panorama or building or view would they like to save and to have in the new one?

The kindergarten children, coordinated by Carla Manfredini, worked with modeling clay on wood tablets. The purpose was to make them think and to model familiar and comfortable spaces they would like to find in the new school.

Boys and girls attending middle school, coordinated by Barbara Badiani, worked on desired spaces to take care of (also for extracurricular activities), reflecting on their sense of responsibility.

5. The Didactical Experience Using Memory-Drawings

The experience I am exposing concerns the Laboratory I carried out with children of elementary school age.

It was focused on the particular location of the former building (and of the new one) in the urban context, interpreted and told by the children through memory-drawings in the first step, by photography in the following one.

The proposed activity, based in the first time just on memories, used two fundamental tools:

freehand memory-drawing, to fix the memory of places before seeing them, and to think about fundamental landscapes or sight-sites both from the school or from the surrounding area;

photography, to later capture inalienable sights to save in the new planning.

Before going out to take pictures, a map of the center of Gualdo (

Figure 4) was shown to the children to draw their attention to the location of the school building in comparison to the surrounding area.

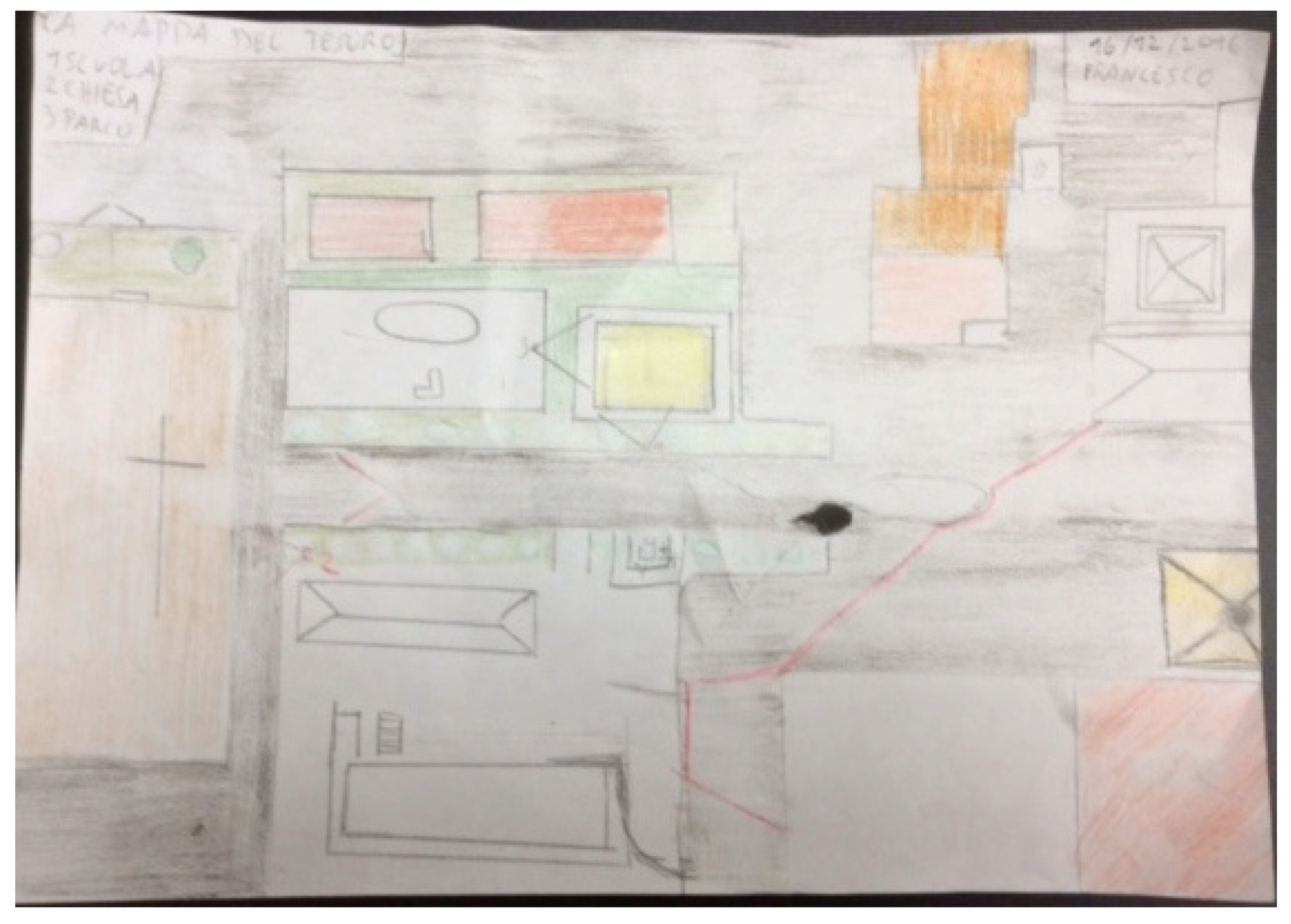

After some observations, the map was hidden. The children were asked to work on their memory of the site, drawing the unchanging spots they would like to preserve in the new project.

They were free to sketch the following: a map, a bird’s eye view, a perspective, a facade.

They had to mark their standpoints from where the pictures would be taken, using the right technical symbol of “V” with a number.

This task, which is not so easy for children in general, was suitable for children of Gualdo, very careful and sensitive due to the difficult experience they underwent, since in half a second their habitual life changed.

Two crucial thoughts emerged at once: Gualdo’s school (blue), due to its location, is a linkage between the historical village where offices and activities and citizens dwell (left), and the ancient monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie presently used as a hospice, where the elderly live (right).

The children identified the downtown as “the heart of the village, where life pulsated |before the heartquake|” and the hospice as “the heart of the memory, where grandparents preserve the history of the community”. Those thoughts demonstrate that the process of identifying surrounding and community values in this young people is advanced and make them able to give clear descriptions.

Moreover, for its physical position on the ridge of the hill, the school (especially from the windows of the first floor) also allows a double panoramic view of the mild landscape of the Marche hills on the north, and of the Sibillini mountains on the south (

Figure 5).

Due to this particularity, throughout the briefing, it was underlined and described as an amazing “view-bridge”.

The drawings made by children in the first step represent their idea of urban spaces and of the urban landmarks they have memorized by frequenting the context in which the school is located. They also demonstrate which signs struck them in the surrounding landscape and what they would like to see from the new school. The ideas of urban space and of the role of the school as fulcrum of the urban system are remarkable.

First of all, many drawings underline the tree-line road (viale Vittorio Veneto) that links the ancient downtown with the hospice: it’s the main boulevard of Gualdo, it has a special rhythm given by tall trees and the school overlooks this public space. In most drawings the trees are drawn and green colored, and they are represented in bird’s eye view or in perspective.

Many sketches illustrate the surroundings up till the village’s heart, Cassero square and Vittorio Emanuele square. In some of them even the ancient tower and the water tower are illustrated, as stand out-signs in the panorama.

But the most meaningful figure is the graphical importance of the crash barriers cross off the ancient destroyed downtown: a red line, very similar to the true one, that dramatically split in two parts the village of Gualdo. This red line is the evidence of the emergency caused by the earthquake and children feel it strongly.

The drawing of Alessandra (

Figure 6) is very symbolic and concise in the same time. She attends only the third elementary school and she is very smart. She represents with a few of signes the downtown in the form of a key: the tree-line boulevard Vittorio Veneto joins the hospice with the heart of the village, piazza del Cassero and Piazza Vittorio Emanuele, that are forbidden to pedestrian people so as to cars, as the red line irremediably remember us.

The circular mode clearly describes the true oval shape of the village, perched on the hillside, while the yellow color chosen for the ancient buildings seems to remember us the warm tonalities of the rock tuff, lighted up by the sun.

6. Taking Photographs at Children Level with Children Eyes

Later, during the survey the students began to take pictures from the standpoints marked on their drawings, to capture inalienable sights to save in the new planning.

With their drawings in one hand, the camera in the other hand, they ran from a standpoint to another, to confirm the sight-site or to adjust their point of view.

What a pity for children cannot enter in the school building, because of its inability, to capture the best views from the windows of the second level! The repeated views they have chosen, indeed, concern to the landscape: mountains and panoramas as far as the eye can see.

So it will be important, after the Laboratory phase, to transmit this need of overviews to the designers and architects to equip many windows for the new building, with the advice to lower window sills (compatibly with security), to allow greater visibility of the landscapes to those who are not tall like an adult.

7. Perceptual Aspects

The children’s choices of the point of view, thanks to their sensitivity, allowed the camera to capture not only the visible but also the invisible data.

I would remember, for example, the particular sensitivity of a girl who wanted to take a not-usual picture. Sofia chose a view from the school garden, in order to catch the wind blowing through a large pine tree.

The European Landscape Convention describe the term Landscape as “an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors” (Article 1—Definitions). The term “perception” allows us to talk about the five senses as a new frontier to better understand the landscape.

We can use Sight, Sound, Smell, Taste and Touch to read the landscape, and every time it will be an exciting experience [

3].

Moreover, in accordance with the provisions of the European Landscape Convention, this Laboratory introduces the “collective dimension” as a relationship between community and landscape.

Those drawings show a remarkable attention to the collective dimension; let me underline that Diego, who is attending fourth of the elementary school, also includes the provisional school in front of the original one, on the other side of the avenue (

Figure 7).

It is important to note the use of colors to highlight only a few data: grey for the streets, green for the trees, and light brown for the temporary school building, realized with wood.

The boy marks several standpoints in his drawing: towards the school, the hospice, the bar, the little gate between the garden of the school and the public park. He is interested about all the architectural elements around the school, except the only that he has colored: the most clear but the most temporary one, the wood provisional building.

8. Pursued and Achieved Goals

The freehand-drawing allowed children to work on memory of spaces and to translate their needs related to their way of seeing and living the landscape and the well-known places. This goal demonstrates that drawing has an essential role of representation to communicate needs, memory and feelings.

In addition, through the mind map and the personal drawings, children were able to reflect on the idea of “community” both in its symbolic form (parents, families, friends) and in its physical structure (the square, the school, the hospice).

The camera subsequently permitted a check of mnemonic data and a critical comparison between mnemonic image and visual reality as photo proves, shot from their height, the one of a child. Photography is confirmed as an extraordinary expressive medium, especially when compared with memory (

Figure 8).

Reflecting on yearning or remembered sight-sites allows to see reality with a new, more inquisitive eye, developing curiosity and sense of observation using all the senses (

Figure 9).

Last but not least, this workshop is congruent with the European Landscape Convention and with Urbani Codex (2004, last revision 2014) which defines landscape as perceived by local people. The Laboratory has been coherent with the guidelines of the European Convention, in accordance with the three steps in the perceptive approach to the landscape: perceiving, reacting, and perceiving perception.

Encouraging the understanding of the “genius loci” guarantees a responsible projection towards the future, starting from your own context, “your home” where historical memories are protect.

9. Conclusions

Children were not only witnesses but also protagonists of a reconstruction of their school.

Thinking about a new building restored their confidence in the future.

Designers can use children’s drawings to enrich the new building, making it better and more comfortable reflecting their own needs and desires.

In conclusion, this Laboratory helped to transform space into landscape, through the perception of the people who live there.