1. Introduction—From La Mémé to Poundbury

In the studio A Survey of Utopia the participating students were asked to create their own filmic travelogue of an excursion to a number of visionary projects, e.g., Lucien Kroll’s la Mémé in Brussels (1968), Walter Segal’s self-build houses in Lewisham (1986) and Leon Krier’s Poundbury, an extension of Dorchester (since the 1980s). The visited projects were chosen with three properties in mind that make them particularly lend themselves to this assignment: First, they were conceived of by their designers as a commentary on and a critique of the contemporary architecture of their time. Second, they are unusual in their materiality, their detailing and their overall design and therefore offer an ‘unusual’ image. Third, enough time has passed since their construction to blend this newness and otherness with traces of decades of use and adaption. It is, therefore, possible to ‘survey’ them and see, if there is a contrast between the utopic ambition of their 1960s–1980s creators and the normality of their everyday use today.

The term ‘survey’ emphasizes the idea that the student works in this studio are not an independent design, but rather an attempt to come to terms with the original intentions of the studied architects and urbanists. However, the students’ short films are not conceived of as straightforward documentaries, but rather at least partly as works of fiction. This mix of genres is inspired by the work of British filmmaker Patrick Keiller, whose well-known film Robinson in Space (1997) uses a pseudo-documentary style that combines documentary film footage with a partly fictional spoken narrative. Through subtly distorting the portrayed reality in the voice-over, his film heightens the audience’s sensitivity for the shown places and prompts it to see them afresh. The psychogeographic writer Ian Sinclair can be seen as another inspiration for this studio. In his case it is not so much the fictionalization of found places that is of interest, but the very personal frame of reference he uses to approach them. This lifts his works beyond the realm of ordinary travelogues. They are as much about the person of the traveller as they are about the visited places. In a similar way, in A Survey of Utopia, the students are prompted to be aware of their own role within their project. Since their work in this studio is not an architectural project in the usual sense but a narration, the question of the narrator’s perspective arises.

It is important to note, that the participants had only limited opportunity to preplan their films. The trip was not organized by them but by the accompanying teachers, and the time schedule (while allowing some free filming time at each project) was not so flexible as to allow many takes. The students mostly saw the projects for the first time, and had to immediately react to the given situation. Therefore, a lot of the conceptual work happened after the trip during editing. In many cases, the students only started to recognize certain patterns and to give their films a clear direction with the benefit of hindsight.

2. Travelling Like Patrick Keiller

A Survey of Utopia aims at a variation on the classical architecture excursion that gives more space for critique, doubt and ambivalence. The narrative of an architectural excursion is usually one of exemplariness. Architecture students travel to places where great architects created great works. The encounter with those works is expected to deeply move the visitors—the architectural excursion as a pilgrimage. This kind of travel can be valuable as an initiation into the profession and helps to establish a canon of exemplary works. However, because of their celebratory nature such trips rarely spur a critical examination of this canon.

The excursion for

A Survey of Utopia, in contrast, takes clues from the way of travelling presented in Patrick Keiller’s films

London (1994) and especially

Robinson in Space (1997). In

Robinson in Space Keiller shows a number of trips through England highlighting places of production and transportation, i.e., factories, harbors and highways. He shows those kinds of places that deal with the reality of providing for the material needs of modern civilization. Often they are places in the periphery of the city, at the seacoast or the countryside that the inhabitant of the city is not aware of, while without them city life would not be possible. As Timothy Corrigan states: “This excursive essay accordingly appears occasionally like a twisted heritage film in which the cultural auras of places become replaced by technological and economic simulacra” [

1] (p. 115). It is important to note, that Keiller does not limit himself in this film to the constraints of a ‚straight-forward’ documentary, but adds fictional layers to his film by introducing two fictional protagonist as the travelers of his journey: Robinson and his assistant, who is the narrator of the film.

3. A Situationist Journey—Drifting and Psychogeography

Keiller’s films make direct reference to 18th century literature, especially to Daniel Defoe’s

Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724–1726). From Defoe’s travelogue Keiller not only takes the idea of a journey through England, but also the stylistic means of dividing the film into several trips. Apart from this structural similarity Keiller’s film is markedly different from its literary inspiration, especially because it is “much more critical of the status quo than Defoe’s Tour, which styles itself ‘a description of the most flourishing and opulent country in the world.’” [

2] (p. 805). Defoe’s description of his trips through England, while being partly invented by the author, is not presented as a work of fiction, but can rather be seen as a journalistic work. Keiller, in contrast to this, interprets the form of the travelogue more freely. Inspired by Situationist ideas, he uses the techniques of

Drifting and

Psychogeography. These techniques were developed in the early 1950s by the

Situationist International (especially Ivan Chtcheglov).

Drifting in this context describes a special way of experiencing the city, “an attempt to orient oneself in the absence of any practical considerations: to find the types of architecture one desired unconsciously.” [

3] (p. 4)

Psychogeography is the “study and correlation of the material obtained from

Drifting. It was used on the one hand to try and work out new emotional maps of existing areas and, on the other, to draw up plans for bodies of ‘situations’ to be interlocked in the new utopian cities themselves.” [

3] (p. 4) There is, therefore, a close connection between a Situationst way of experiencing the city and the idea of a utopian city. The use of Situationist techniques is what makes Keiller’s films such an inspiration for the studio

A Survey of Utopia.

4. Utopia and Failure

Keiller’s interest in Situationism is also the reason for the lingering sense of futility that permeates his travelogue. As Robert Mayer states in his essay on Keiller’s films: “The situationist enterprise is visionary and utopian but it is also dogged by a sense of inevitable failure, at least in the short term.” [

2] (p. 815) The connection of utopia and failure is programmatic in Keiller’s films. This is illustrated by two quotations that the narrator in “Robinson in Space” uses in the voice-over (without giving their source):

In the opening scene of the film the voice-over uses a text by Raoul Vaneigem: “I am struck by everything and, though not everything strikes me in the same way, I am always struck by the same basic contradiction: although I can always see how beautiful anything could be if only I could change it, in practically every case there is nothing I can really do. Everything is changed into something else in my imagination, then the dead weight of things changes it back into what it was in the first place. A bridge between imagination and reality must be built.” [

4] (p. 245)

Early in the film the voice-over uses a passage from Henri Lefebvre’s The Production of Space: “The fact is that the space which contains the realized preconditions of another life is the same one as prohibits what those preconditions make possible.” [

5] (p.189, 190)

The form of the essay film gives Keiller the possibility to create films that work as a commentary and/or meditation on these dilemmas without having to resolve them. Through his particular technique of juxtaposing documentary film scenes with a voice-over that ranges from pure description of the depicted scene to completely fictional or philosophical statements, Keiller arrives at scenes in which both the images and his words become suspicious to the audience. This technique of an untrustworthy narration communicates the feeling of

Drifting to the audience. The resulting tension also shows that Keiller’s reference to Lefebvre goes deeper than just quoting a passage from

The Production of Space. Keiller’s film explores Lefebvre’s dialectic of the three moments of space, the perceived (perçu), the conceived (conçu) and the lived (vecu). “Robinson in Space is an exceptionally mobile, ironic, and critical interlocking of these spaces as the travelers overlay lived experiences, their geographical representations, and the struggle to infuse them with shape, ideas, and value, a struggle that ultimately fails to cohere as a ‘dwelling’ and leaves Robinson a drifting subject in both a figurative and a real outer space.” [

1] (p. 119)

5. The Design Studio

A Survey of Utopia invited the students to create their own filmic travelogue that equally rejects coherence in favor of a more layered and poetic approach to the visited places and buildings. It shares Keiller’s interest in the material products of society and like Keiller makes reference to Lefebvre‘s concept of spatial practice, especially to the idea, that it can only be investigated by deciphering a society’s spaces: “The spatial practice of a society secretes that society’s space; it propounds and presupposes it, in a dialectical interaction; it produces it slowly and surely as it masters and appropriates it. From an analytical standpoint, the spatial practice of a society is revealed through the deciphering of its space.” [

5] (p. 38)

However, in contrast to Keiller’s journeys, the special aspect of “A Survey of Utopia” is that its journey is not set out along factories, harbors and superstores, but along visionary residential building projects from the 1960s to 1980s. The visited projects share that they all make critical statements on the reality of dwelling in their time and that they propose at times drastic alternatives to those realities. This connects the visited projects even though they have no direct links with each other, and even though the ‘utopias’ they propose are very different from one another. In this sense, the journey aims to be a survey of what constitutes the ‘utopian’ in each visited project.

5.1. Utopia in Pieces (Anne Effkemann)

Anne Effkemann uses a collage technique to compose her travelogue “Utopia in Pieces”. The visited projects are shown in fragments, in still images zoomed in on façade details, windows, brick masonry, entrance doors and drainpipes. This simple stylistic choice has a disorienting effect, as the shown details often are difficult to assign to a specific project. Since no overview images structure the film, it often remains unclear which part of which project is being shown. Effkemann adds to this effect by mixing the images of the projects, thereby not only interfering with the chronology of the presented journey, but also with the creation of a coherent image of the presented projects (

Figure 1).

The voice-over is using passages of texts on the visited projects, either written by the architects or by (admiring) critics. They are, therefore, texts that not only describe the projects, but also point out their visionary features, and the visionariness of their designers. In the film’s voice-over, these passages, too, are composed in a collage style, leading to the voice-over often describing another project than the images show. Consequently, the survey is completely mixed up. Texts on Lucien Kroll’s La Mémé are read to images of Walter Segal’s self-build houses. Texts by Leon Krier on his plans for Poundbury are read while images of Henri Guchez’ Cité Hadés are shown, all the while the images of these projects themselves are not in coherent order.

The rejection of coherence is consequently perhaps the strongest statement of this film. Following Keiller’s example, Effkemann evokes the feeling of Drifting in her film. Seen as an ironic commentary, the film might point to the perception, that the utopian projects are after all ‘not that different’, putting the often unremarkable images in contrast to the celebratory language of the accompanying texts. But the film never makes this critique explicitly, which leaves it open to other interpretations. One could just as well understand it as claiming that all depicted projects are ultimately one. Through its fragmented view of the projects and its mixing of their fragments, the film blends them with each other, creating one unified utopian project.

5.2. Social Housing in London (Vanessa Koepper)

Vanessa Koepper’s film edits the journey very selectively. She presents it as a visit to only one project, Walter Segal’s self-build houses in Walter’s Way and Segal Close in Lewisham, South-London. The film follows a compelling story arc. In the beginning Walter’s Way is shown as a pristine living environment in the green. There are almost no people in the images and the sound of birds and the wind in the leaves are all that is heard. When one reads the caption “Walter Segal´s vision today”, it appears as if utopia has in fact been realized. Slowly, however, from scene to scene the spaces become busier with people. The visiting group is intruding in this idyll. Often filming through the panes of glass doors or windows, Koepper takes the perspective of a hidden inhabitant, someone watching the intruders with apprehension (

Figure 2).

The cathartic moment of the film is the scene of the ‘book sale’. While one of the inhabitants, a photographer who offered a tour of his house, sells his newly-published book to the group of visitors, one hears the conversation between him and the visitors. The commercialization of the project is revealed, while the camera—instead of showing the protagonists of the sale—is fixed on a photo of Walter Segal that lies on the living room table. A strong scene in which the visionary designer ‘witnesses’ the desecration of his work (

Figure 3).

In a final scene, the film cuts away from the cheering that accompanies the book sale. The camera captures a serene scene on the terrace of one of the houses. Nobody can be seen or heard, only the wind in the leaves of the trees. Two captions are shown: “Building cost: 2500£”, “Sales value today 250,000£” (

Figure 3). They confirm what the viewer knows already now. The idyllic images are a deception. The original participatory values of the project have long been hollowed out by the forces of the property market.

In a surprising turn of perspective Koepper’s film questions not only the utopian quality of the visited project and the motives of its inhabitants but also the motives of the visitors themselves. It uses a narrative perspective that disassociates the narrator of the film from the travellers visiting the project, enabling it to expose their hidden agenda (of consumption).

In its use of a classical story arc, the film stylistically departs from the path set out by Keiller’s films. In its critique of the capitalist influence on the visited project it nonetheless takes up a line of argument that runs through Keiller’s films as well. It shows and implicitly denounces the unbound market forces that have subverted the idea of Walter Segal’s self-build settlement. This resonates with Robinson in Space, which shows the erosion of the idea of unionized labor in England through similar market forces—this is explicitly pointed out in a scene, in which Robinson and his companion visit recently privatized port facilities.

5.3. A Bus Ride to Utopia (Conrad Risch, Jonathan Schmalöer)

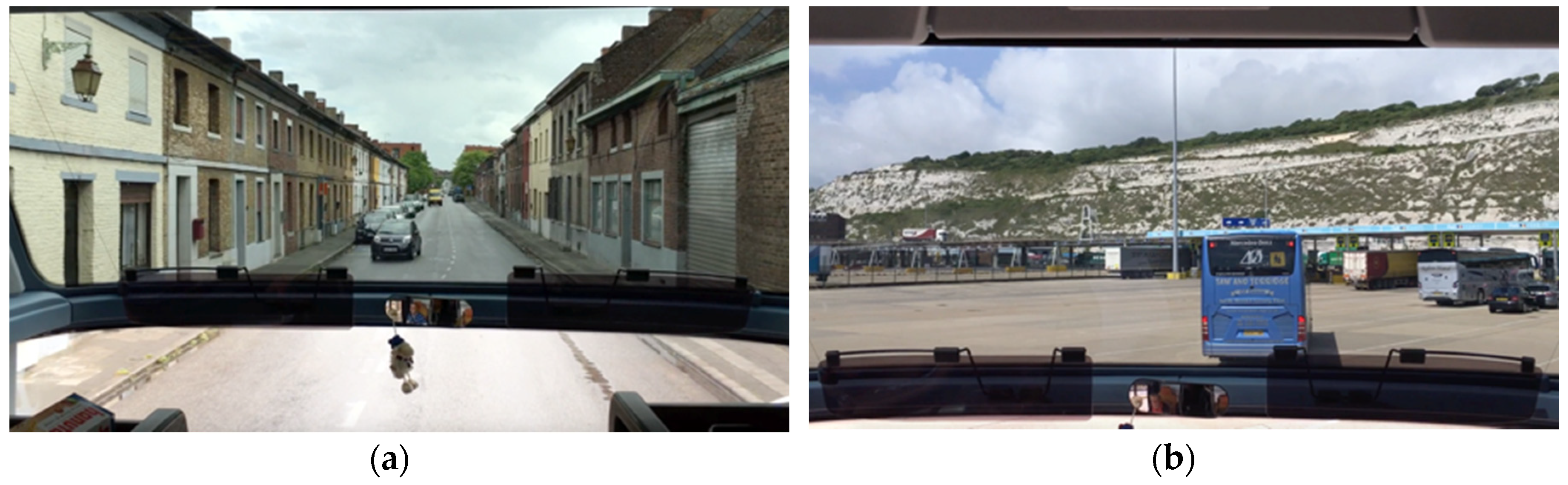

The special approach of this film is that it mostly omits the actual topic of the trip (i.e., the visited projects) in favor of showing those aspects of the excursion one normally would not pay much attention to: the bus ride, the ferry connection across the Channel or the students sleeping in their bus seats. Often the camera is positioned in the aisle of the bus filming through its large windscreen as it slowly moves through narrow streets. It becomes clear that the visited utopias are not in the urban centers; they are in small towns or suburbs, where the streets are deserted. There is something ‘outsized’ about the vehicle the travellers use to approach the visited projects. The heightened viewpoint in the bus gives them a superior position, like surveyors overlooking the land. They are clearly not blending in with their environment. Are their instruments not too blunt to be able to adequately survey the subtleties of the visited places (

Figure 4)?

For a soundtrack, the film relies on conversations recorded in the bus that are mainly about the technicalities of travelling, like finding the hotel or looking for a parking spot. It also repeatedly cuts to the song Died in Your Arms by Cutting Crew (1986). This is an ironic reference to the 80s radio station the bus driver listened to during the trip, but it also serves to portrait the trip as slow and nostalgic. It points out the old-fashioned way of travelling that makes the travellers feel the distance.

A Bus Ride to Utopia leaves the viewer with the impression, that the travellers never really leave the bus. If the visited projects are shown at all, they usually appear in a separate window superimposed over film scenes showing the bus ride. In this take on the trip, the film makes a strong statement of the futility of the whole enterprise of surveying utopia. The travellers remain in their bubble. Only the environment of the bus is ever ‘real’ to them, while the deserted and hard to approach utopias allow no real interaction.

6. Conclusions

The design studio A Survey of Utopia places personal experience central in dealing with the visited residential projects. Through the medium of the filmic travelogue the student works explore a practice that allows their experience to enter the work without leading to mere arbitrariness. The Situationist techniques that are being explored allow for a wide spectrum of approaches from films that remain more ‘on the surface’ of the visited projects and mainly deal with their aesthetics to films that make their commentary as a pointed critique. Seeing the student works produced in A Survey of Utopia, a number of potentials of the filmic travelogue in architectural design education can be pointed to:

First, by creating their own narratives based on existing visionary architectural projects, the students were encouraged to question the prevailing narratives of the visited projects. This offered a rich field of exploration. Using literature on the projects, students were able to research the ideas behind them stated by their architects, or find out how critics viewed them at the time of their creation and later. This allowed them to place the commentary of their films within an existing discourse. Of the student works presented in this paper, Vanessa Koepper’s film is the best example for this approach. In Walter Segal’s concept for his wooden self-build houses, the reduction of material cost and work hours is the single most important parameter. Pointing out the changed economical conditions of the project today, Koepper’s film critically engages with a key aspect of Segal’s ideas. It is remarkable that the medium of the film essay allows her to do so without being blind to the beauty of his buildings.

Second, the students had the opportunity to let the images ‘lead the way’. This aspect of the assignment proved especially productive, because most of the visited projects offered so specific environments, that the students’ films achieved a dense atmosphere and aesthetic in their images without having to particularly force this. The strong images in turn gave the films a focal point around which their narrative could develop. Through this primacy of the image, films could intentionally ‘misread’ the visited projects. They did not have to strive for realism, but could explore where a free interpretation of the images would lead them. Anne Effkemann explores this route, when she structures her travelogue by composing corresponding images from different projects. Consequently, her film jumps in time and place, mixing up the actual sequence of the trip and even mixing up the texts that are read as a voice-over. This working method also corresponds to the fact that most students only found the final concepts of their films after the excursion when reviewing their images in the cutting room.

Third, the films had the potential to be a commentary on the idea of an architectural excursion as such. The trip was conceived of as an alternative to the usual architectural excursion to begin with. Some students seized on this aspect to make their film a critical consideration of the way they travelled. The film A Bus Ride to Utopia is using irony to point out the dubiousness of the notion of an alternative kind of excursion. It questions if one can actually ‘drift’ in a large group of students.

Thus, while a variety of approaches could be taken in the creation of the filmic travelogues, all films share one characteristic. They all reinterpret the trip for their own work and are able to present it according to their own chosen narrative. This appears to be the main potential of this kind of design studio—giving the students the opportunity to apply narrative to architectural projects that are not their own creation, but that become gradually appropriated, as their images become parts of the students’ films.

The final concepts of most films were only decided on in the cutting room. Because of the very limited opportunity to preplan the films, most students shaped their narrative when editing the raw footage. This defines the didactic outcome of the studio. The students learn about storytelling and editing, but relatively little about scripting and planning a film in advance. In the context of Situationist techniques, however, the emphasis on spontaneity prompts the students to be open and perceptive while traveling, which is perhaps the most important didactic result this studio aims at.