Share and Communicate the Cento Città d’Italia: From the XIX to the XXI Century †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Context

3. Approaches and Methodologies

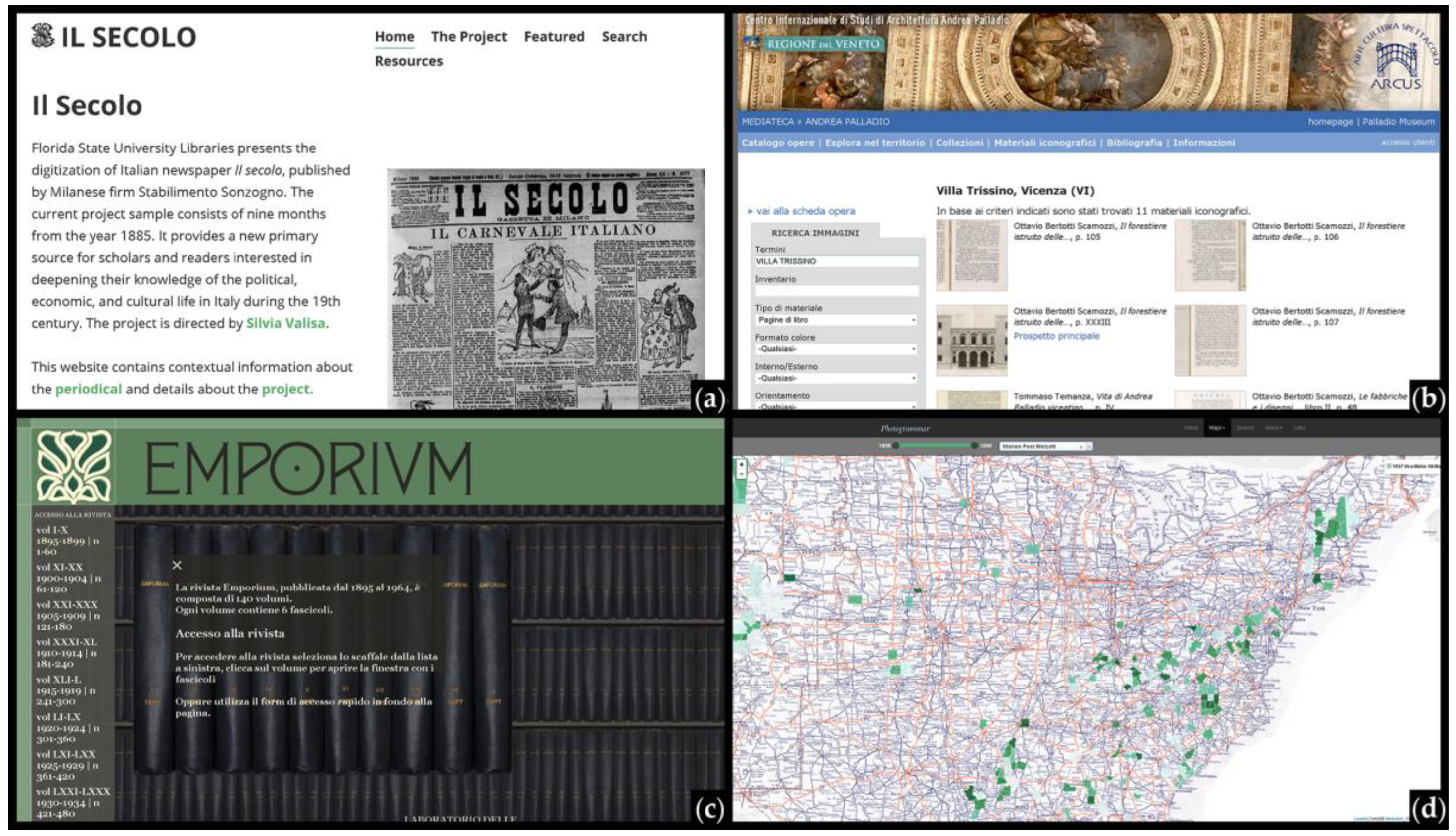

3.1. References for a Meta-Project: Data and Database

3.2. References for a Meta-Project: From Raw Data Storage to Its Visual Management

3.3. From the Meta-Project to the Project

“The geographic component of cultural heritage information makes a leap of quality into the systems of knowledge organization, as an indispensable background for any instrument of knowledge, analysis, intervention. In this perspective, geographic information systems allow to consider the cultural heritage in its entirety, entrusting the new role of systemic cultural good to the natural and anthropic landscape, an expression of the whole system of relationship between the individual goods and between them and the context itself” [19] (p. 241).

- (a)

- IGMI (Italian Military Geographic Institute) 250 Series—Italian Regions (scale 1:250.000) WGS 84 geographic referenced, which allow the entire territory to be surveyed and to propose a double synchronous and diachronic reading.

- (b)

- IGMI (historical maps), sheet of Carta d’Italia, 1884 (Maps of Italy, scale 1:500.000), referring to the territory under consideration. As soon as this is a historical cartography made available in digital format, its potential lies in the possibility of displaying data referring to the geographical situation of the Kingdom of Italy as represented in the same years of publication of the CC.

- (c)

- Carta delle strade ferrate italiane al 1o aprile 1889 (Italian Railways Chart on 1 April 1889, published for the care of the R. Ispettorate Generale delle Ferrate by the Italian Geographic Institute, scale 1:1.500.000). This chart, as already pointed out in a previous work [13], can be of great interest as the graphic information contained in the CC can be related, (since many descriptions have explicit references) to the logistic system of that time in Italy.

3.4. Territorial Sample

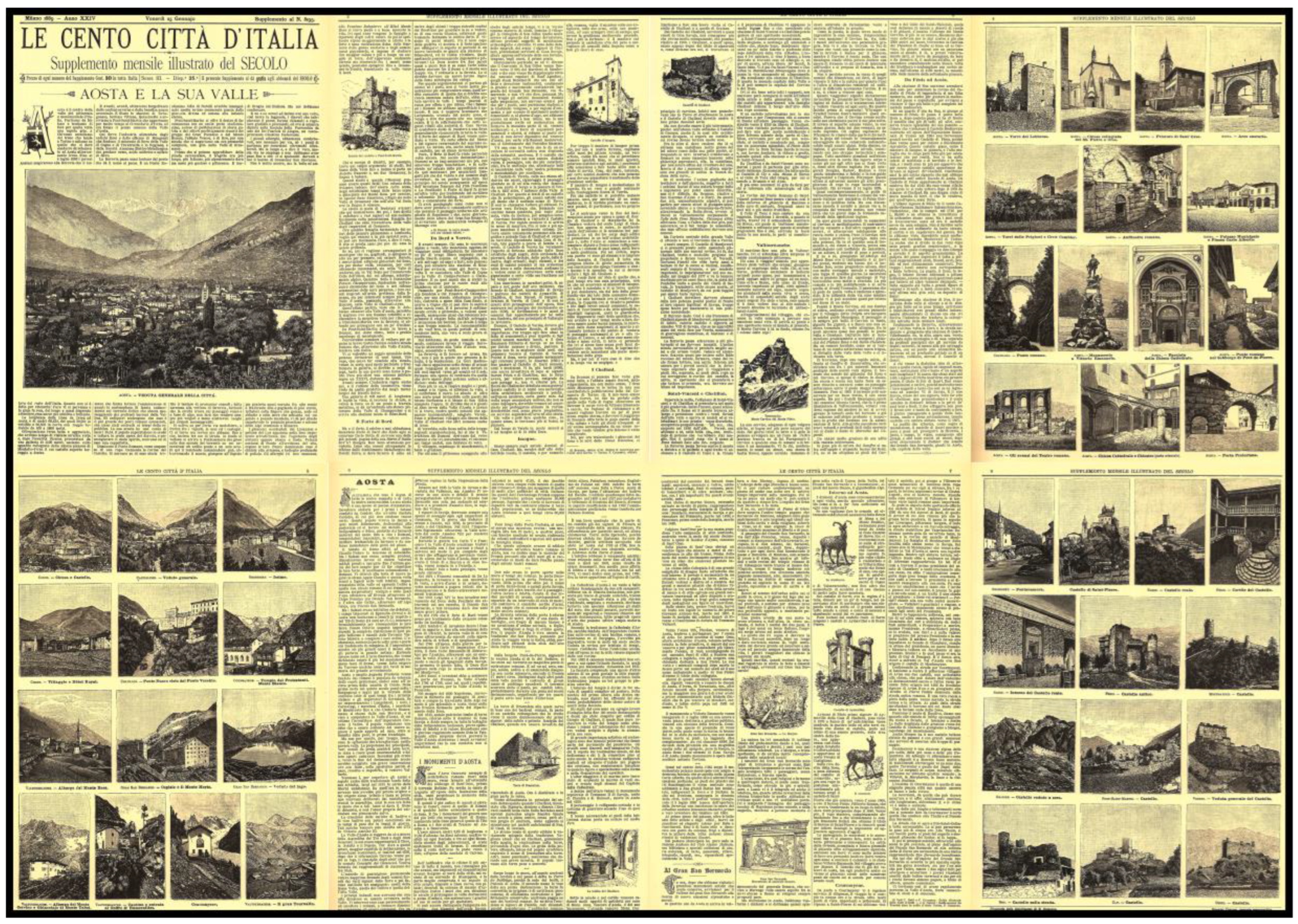

4. Analysis and First Outcomes

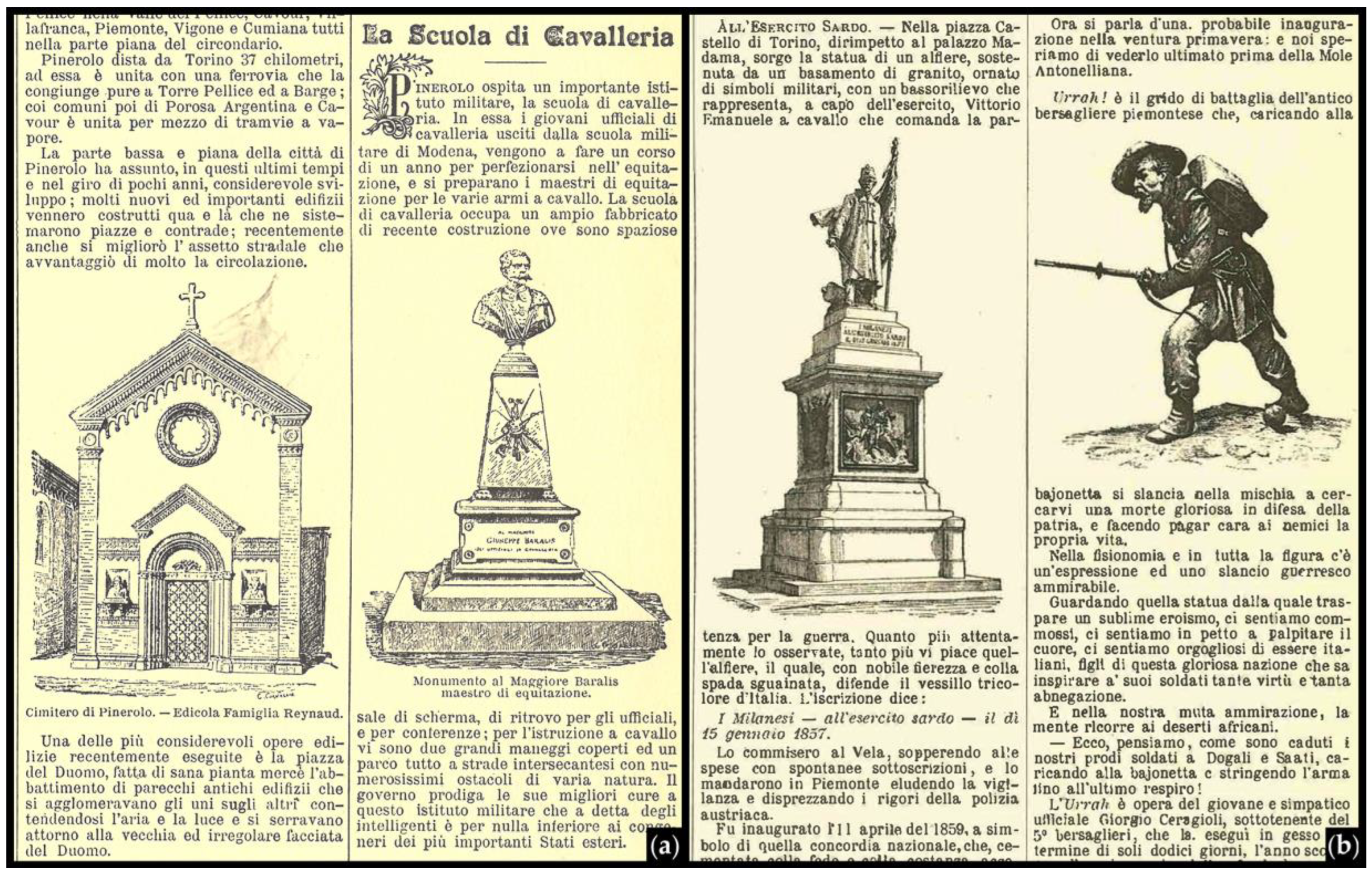

“Urrah! è il grido di battaglia dell’antico bersagliere piemontese che, caricando alla bajonetta si slancia nella mischia a cercarvi una morte gloriosa in difesa della patria, e facendo pagar cara ai nemici la propria vita. Guardando quella statua dalla quale traspare un sublime eroismo, ci sentiamo commossi in petto a palpitare il cuore, ci sentiamo orgogliosi di essere italiani, figli di questa gloriosa nazione che sa insipirare a’ suoi soldati tante virtù e tanta abnegazione. E nella nostra muta ammirazione, la mente ricorre ai deserti africani.—Ecco, pensiamo come sono caduti i nostri prodi soldati a Dogali e Saati, caricando alla bajonetta e stringendo l’arma fino all’ultimo respiro! L’Urrah è opera del giovane e simpatico ufficiale Giorgio Ceragioli, sottotenente del 5° bersaglieri, che la eseguì in gesso nel termine di soli dodici giorni, l’anno scorso per l’anniversario della fondazione del corpo dei bersaglieri. Ora per ordine del Ministero della Guerra la statua viene fusa in bronzo al nostro arsenale: e verrà collocata in qualche museo”. [26] (p. 59).

“Oltrepassiamo Ivrea bella e aggraziata, che avremo tempo di visitare un’altra volta e, dopo l’oscuritàà forzosa procurataci da una galleria di 1109 metri, usciamo collo sguardo rallegrato dalla amena pianura di Montalto-Ivrea, il cui castello superbo, torreggia a destra” [27] (p. 1).

“E avanti, avanti, attraverso Borgofranco dalla cantine-caverne e dalla benefica acqua arsenicale. E sfilano le stazioni di Tavagnasco, Settimo Vittone, Quincinetto e arriviamo a Pont-Saint Martin che appartenne per molto tempo al Circondario d’Ivrea, ed ora forma il primo comune della Valle d’Aosta” [27] (p. 1).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Marchis, E.T.C.; Pavignano, M.; Zich, U. The fortifications on a Citizen scale. Analysis of visual storytelling of Ligurian cities in “Supplemento mensile illustrato del SECOLO” (1887–1902). In Defensive Architecture of the Mediterranean XV to XVIII Centuries; Verdiani, G., Ed.; Didapress: Firenze, Italy, 2016; pp. 405–412. ISBN 9788896080603. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, S. La rappresentazione, ovvero: Geografie dello sguardo. In Riflessi Italiani: L’identità di un Paese Nella Rappresentazione del suo Territorio; Conti, S., Ed.; TCI: Milano, Italy, 2004; pp. 8–11. ISBN 9788836531295. [Google Scholar]

- Gigli Marchetti, A. Le nuove dimensioni dell’impresa editoriale. In Storia Dell’editoria Nell’italia Contemporanea; Turi, G., Ed.; Giunti: Firenze, Italy, 1997; pp. 113–164. ISBN 8809212363. [Google Scholar]

- Pallottino, P. Il mondo a dispense. In Storia Dell’illustrazione Italiana. Cinque Secoli di Immagini Prodotte; Pallottino, P., Ed.; Uscher Arte: Firenze, Italy, 2010; pp. 235–256. ISBN 9788895065465. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, G. Le illustrazioni in Italia tra Otto e Novecento: Libri a Figure, Dinamiche Culturali e Visive; Olschki: Firenze, Italy, 2009; ISBN 9788822259301. [Google Scholar]

- Forgnacs, D. L’industrializzazione della cultura italiana (1880-2000); Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, F. Architettura in quanto immagine: Spazio contro tempo. In Idee per la Rappresentazione 7—Visualità; Atti del Seminario di Studi; Belardi, P., Ed.; Artegrafica: Roma, Italy, 2015; pp. 219–237. ISBN 9788890458590. [Google Scholar]

- Valisa, S. Casa editrice Sonzogno: Mediazione culturale, circuiti del sapere ed innovazione tecnologica nell’Italia unificata (1861–1900). In The Printed Media in Fin-de-Siècle Italy; Hallamore Caesar, A., Romani, G., Burns, J., Eds.; Legenda: London, UK, 2011; pp. 90–106. ISBN 9781906540746. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, G. XX”. In Emporium. Parole e Figure tra il 1895 e il 1964; Bacci, G., Ferretti, M., Fileti Mazzia, M., Eds.; Edizioni della Normale: Pisa, Italy, 2009; pp. 95–153. ISBN 9788876423642. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, D. Memoria ed immagine del territorio fra testimonianze artistiche e bellezze naturali. In Emporium. Parole e Figure tra il 1895 e il 1964; Bacci, G., Ferretti, M., Fileti Mazzia, M., Eds.; Edizioni della Normale: Pisa, Italy, 2009; pp. 235–270. ISBN 9788876423642. [Google Scholar]

- Pavignano, M.; Zich, U. Different matrixes of Sicilian landscapes in Le Cento Città d’Italia. Social identity, cultural landscape and collective consciousness in-between texts and images. In Putting Tradition into Practice: Heritage, Place and Design, Proceedings of 5th INTBAU International Annual Event, Milano, Italy, 5–6 July 2017; Amoruso, G., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer Intl Pub. AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 3, pp. 823–833. [Google Scholar]

- Bellocchi, U. Saggio introduttivo. In Le Cento Città d’Italia. Supplementi Mensili Illustrati de Il Secolo. Milano, Edoardo Sonzogno Editore, 1887–1902; Intl Ad. Company: Bologna, Italy, 1983; pp. VII–XX. [Google Scholar]

- Pavignano, M.; Zich, U. La narrazione dei paesaggi nell’Italia post-unitaria: Sonzogno divulgatore. Narration of the post-unitary Italian landscape: Sonzogno popularizer. In Delli Aspetti de Paesi. Vecchi e Nuovi Media per L’IMMAGINE del Paesaggio; Berrino, A., Buccaro, A., Eds.; CIRICE: Napoli, Italy, 2016; pp. 1153–1162. ISBN 9788899930004. [Google Scholar]

- Zich, U.; Comollo, U.; Pavignano, M. Turin in “Le Cento Città d’Italia”: Sonzogno publisher representing and narrating a reality in transformation between the XIX and XX centuries. In Drawing and City/Culture, Art, Science, Information; 37° Convegno Internazionale dei Docenti della Rappresentazione; Marotta, A., Novello, G., Eds.; Gangemi: Roma, Italy, 2015; pp. 1203–1212. ISBN 9788849231243. [Google Scholar]

- Marotta, A. Metodologie di analisi per l’architettura: Il Rilievo come conoscenza complessa in forma di database. In Sistemi Informativi Integrati per la Tutela, la Conservazione e la Valorizzazione del Patrimonio Architettonico e Urbano; Brusaporci, S., Brusaporci, S., Eds.; Gangemi: Roma, Italy, 2010; pp. 69–141. ISBN 9788849218602. [Google Scholar]

- Beltramini, G.; Gaiani, M. Dalla grammatica palladiana alla Palladio Library: Piccola storia del sistema comunicativo-informativo palladiano. In Palladio Lab—Architetture Palladiane Indagate con Tecnologie Digitali; Beltramini, G., Gaiani, M., Eds.; CISA AP: Vicenza, Italy, 2012; pp. 9–17. ISBN 9788884180971. [Google Scholar]

- Boido, M.C. Il processo di conoscenza tra storia e rilievo. In Rilievo Urbano. Conoscenza e Rappresentazione Della Città Consolidata; Coppo, S., Boido, M.C., Eds.; Alinea: Firenze, Italy, 2010; pp. 50–79. ISBN 9788860555366. [Google Scholar]

- Marotta, A.; De Berdardi, M.L.; Bailo, M. La conoscenza di architettura, città e paesaggio: “Il Progetto Logico di Rilievo” in una sperimentazione metodologica. Disegnarecon 2008, 1, 1.2–1.13. [Google Scholar]

- Ippoliti, E. Mappe, modelli e tecnologie innovative per conoscere, valorizzare e condividere il patrimonio urbano. In dagini sperimentali di sistemi integrati sul Piceno. In Sistemi Informativi Integrati per la Tutela, la Conservazione e la Valorizzazione del Patrimonio Architettonico e Urbano; Brusaporci, S., Ed.; Gangemi: Roma, Italy, 2010; pp. 240–251. ISBN 9788849218602. [Google Scholar]

- Ardissono, L.; Lucenteforte, M.; Savoca, A.; Voghera, A. GroupCollaborate2: Interactive Community Mapping. In UMAP 2014 Extended Proceedings; Cantador, I., Chi, M., Eds.; RWTH: Aachen, Germany, 2014; pp. 45–48. ISSN 1613-0073-2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fatta, F.; Bassetta, M.; Mant, M. Reggio Calabria museo di se stessa. Progetto per un museo interattivo della città. Reggio Calabria, Museum of itself. Project for an interactive Musem of the City. Disegnarecon 2016, 9, 5.1–5.16. [Google Scholar]

- Gambi, L.; Merloni, F. (Eds.) Amministrazioni Pubbliche e Territori in Italia; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1995; ISBN 8815050892. [Google Scholar]

- Merlotti, A. Il Piemonte. Le evoluzioni di un’identità da Stato sabaudo a regione italiana. Stud. Piedmont. 2011, 40, 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Castronovo, V. (Ed.) Storia Delle Regioni Italiane Dall’unità a Oggi. I. Il Piemonte; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Salviati, M.; Sciolla, L. (Eds.) L’Italia e le sue Regioni. Istituzioni; Istituto Della Enciclopedia Italiana G. Treccani: Roma, Italy, 2015; Volume III, ISBN 9788812005314. [Google Scholar]

- Torino. Le Cento Città d’Italia. Supplemento Mensile Illustrato del Secolo 1887, I, 57–64.

- Aosta e la sua Valle. Le Cento Città d’Italia. Supplemento Mensile Illustrato del Secolo 1889, III, 1–8.

- Pinerolo. Le Cento Città d’Italia. Supplemento Mensile Illustrato del Secolo 1891, v, 17–24.

- Chieri. Le Cento Città d’Italia. Supplemento Mensile Illustrato del Secolo 1895, IX, 89–96.

- Chivasso e Dintorni. Le Cento Città d’Italia. Supplemento Mensile Illustrato del Secolo 1899, XIII, 1–8.

- Ivrea e il Canavese. Le Cento Città d’Italia. Supplemento Mensile Illustrato del Secolo 1899, XIII, 57–64.

- Susa e Dintorni. Le Cento Città d’Italia. Supplemento Mensile Illustrato del Secolo 1902, XVI, 33–40.

- Torino Nuova. Le Cento Città d’Italia. Supplemento Mensile Illustrato del Secolo 1902, XVI, 73–76.

- Appiano, A. Manuale di Immagine. Intelligenza Percettiva, Creatività, Progetto; Meltemi: Roma, Italy, 1998; ISBN 9788869163791. [Google Scholar]

| Image | Dimensions (mm) * | Type | Caption ** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n° | Name | p. | Base | Height | in Text | in Text Page | in Only Images Page | |

| 1 | MONUMENTO AL PRINCIPE AMEDEO | 73 | 247 | 287 | X | Yes | ||

| 2 | Cappella del Santo Sudario nella cattedrale di San Giovanni | 74 | 59 | 72 | X | Yes | ||

| 3 | Maschio della Cittadella | 74 | 59 | 41 | X | Yes | ||

| 4 | Palazzo della Banca Commerciale Italiana | 75 | 88 | 73 | X | Yes | ||

| 5 | Tempio Crematorio | 75 | 59 | 44 | X | Yes | ||

| 6 | Monumento a G. B. Bottero | 75 | 59 | 73 | X | Yes | ||

| 7 | Gustavo Modena | 75 | 35 | 59 | X | Yes | ||

| 8 | Monumento a Benedetto Brin | 75 | 59 | 73 | X | Yes | ||

| 9 | Monumento a Vittorio Emanuele | 76 | 124 | 149 | X | Yes | ||

| 10 | Monumento a Giuseppe Garibaldi | 76 | 125 | 149 | X | Yes | ||

| 11 | Via Pietro Micca | 76 | 83 | 98 | X | Yes | ||

| 12 | Moumento al generale Alfonso La Marmora | 76 | 74 | 99 | X | Yes | ||

| 13 | Via Quattro Marzo | 76 | 84 | 99 | X | Yes | ||

| 14 | Monumento al generale Carlo Nicolis di Robilant | 76 | 60 | 80 | X | Yes | ||

| 15 | Ricordo di Re Umberto a Superga | 76 | 60 | 80 | X | Yes | ||

| 16 | Monumento della Crimea | 76 | 60 | 80 | X | Yes | ||

| 17 | Monumento a Galileo Ferraris | 76 | 60 | 80 | X | Yes | ||

| Issue | Images | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Vol. | Date | n | pp | pp n | in Text | In Text Page | in Only Images Page | w/o Caption | Per Issue |

| TORINO | I | 25 August 1887 | 8 | 57–64 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 25 | 7 * | 34 |

| AOSTA E LA SUA VALLE | III | 25 January 1889 | 25 | 1–8 | 8 | 11 | 1 | 40 | 0 | 52 |

| PINEROLO | V | 25 March 1891 | 51 | 17–24 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 19 | 0 | 25 |

| CHIERI | IX | 31 December 1895 | 108 | 89–96 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 24 |

| CHIVASSO E DINTORNI | XIII | 31 January 1899 | 145 | 1–8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 18 | 0 | 23 |

| IVREA E IL CANAVESE | XIII | 31 August 1899 | 152 | 57–64 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 23 |

| SUSA E DINTORNI | XVI | 31 May 1902 | 185 | 33–40 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 22 | 0 | 31 |

| TORINO NUOVA | XVI | 31 October 1902 | 190 | 73–76 | 4 | 7 | 1 ** | 9 | 0 | 17 |

| Totals | 60 | 55 | 8 | 166 | 9 | 229 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zich, U.; Pavignano, M. Share and Communicate the Cento Città d’Italia: From the XIX to the XXI Century. Proceedings 2017, 1, 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090924

Zich U, Pavignano M. Share and Communicate the Cento Città d’Italia: From the XIX to the XXI Century. Proceedings. 2017; 1(9):924. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090924

Chicago/Turabian StyleZich, Ursula, and Martino Pavignano. 2017. "Share and Communicate the Cento Città d’Italia: From the XIX to the XXI Century" Proceedings 1, no. 9: 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090924

APA StyleZich, U., & Pavignano, M. (2017). Share and Communicate the Cento Città d’Italia: From the XIX to the XXI Century. Proceedings, 1(9), 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090924