2.1. Ethical Consumption

This study on the role of businesses in bringing funds and shaping ideas around humanitarianism is situated in debates around ethical consumption. Lekakis describes ethical consumption as “the broader phenomenon of ethical behavior in the marketplace” [

2] (p. 8). Complementing the work of human rights NGOS and humanitarian agencies, the market has emerged as a site to both raise issues of injustice and promote forms of social, and possibly political, action. At the very least, the consumer’s ability to exercise “personal choice in the marketplace enables public forms of political expression” that signal an engagement in social, economic, and environmental concerns (p. 9). That business is at the forefront of this ethical activity is a twist; rather than participating in boycotts to protest oppressive states or corrupt businesses, consumers now look to businesses to help them act on their ethical dispositions. A wide range of ethically labelled products greets us in the supermarket and shopping mall (or in fair trade stores), offering the possibility of engaging with a vast array of local, national, or global causes.

Since the 1980s, the fair trade model has offered a way to ensure just treatment of laborers and the environment at the site of production. Labels, certification programs, and supply chain transparency characterize this form of ethical consumption. A different set of practices has taken root through cause-related marketing (CRM), a model that “pairs the support of a charitable cause with the purchase or promotion of a service or product” [

3] (pp. 51–52). As a feature of many corporate social responsibility platforms, CRM enables a company to fulfill its commitments to local or global causes beyond simply sponsoring a charity. Among its product lines, the corporation will distinguish certain products as purchases that will generate a donation. Thematic ties might link the brand to a beneficiary charity; for example, a portion of the price of a package of Pampers diapers is directed to UNICEF (see

Figure 1).

From the business perspective, CRM is a win-win for all participants: charities raise funds and educate consumers while corporations increase revenue and staff loyalty, enhance reputations, and gain market share for their brands. Criticism, however, has been directed towards the full extent of the social impact beyond the act of fundraising; for example, Ikenberry finds fault with CRM’s promotion of “individual solutions to collective social problems, distracting our attention and resources away from the neediest causes, the most effective solutions, and the act of critical questioning itself” [

3] (p. 52). Rather than engage in politics to address the root causes of issues such as poverty, consumers simply signal their concern through the marketplace. Still, as the CRM model continues to enjoy success, it is important to apply visual analysis to detect the “humanitarian imaginary” that constructs ideas of “collective social problems”, “effective solutions”, and “critical questioning”, however limited or obfuscating these ideas may be.

How does the commodification of the same product for purchase and donation offer new opportunities for shaping the “humanitarian imaginary”? In the most recent chapter of CRM, there has been the emergence of a more ambitious form of social entrepreneurship with the company styling itself as a social mission. Founded in 2006, TOMS Shoes was the first private for-profit company to be established on a Buy One Give One (B1G1) model, where all the merchandise constitutes branded products that trigger donations or in-kind contributions. This strategy has been championed as “an effective model for creating both commercial and social value” [

5] (p. 28); there are even online marketplace companies that show would-be ethical consumers the many brands that operate on the B1G1 model [

6,

7]. Recipients of the model range from homeless populations to the hungry to children without access to schooling or adequate health care. B1G1 companies might give monetary donations structured as school fees, microloans, or the purchase of school meals or bio-sand filters; in-kind donations might be clothing, school supplies, baby outfits, toothbrushes, or backpacks [

5] (p. 32). The partner organizations that help with distribution of donations include domestic nonprofits as well as large humanitarian agencies such as CARE and Partners in Health. If the predictions are true and the B1G1 model will continue to occupy greater market share in the sphere of CRM, we need to consider the ways B1G1 companies shape a “humanitarian imaginary” and present a certain mode of ethical consumption as a lifestyle choice with an impact on social issues.

2.2. Symbolic Value of the B1G1 Model

As a source of new funds, actors, and audiences for development causes, CRM has drawn the intense scrutiny of development scholars and political economists. Ponte and Richey have studied CRM campaigns through a conceptual model they call “Brand Aid”, in which causes, branded products and celebrities are linked [

1]. Ponte and Richey regard the various interfaces as ‘regimes of value’, following Appadurai, that produce imaginaries with material and symbolic value. Thus, new humanitarian imaginaries are forged through CRM “in which consumption becomes the mechanism for action and purchase creates a partnership” linking individual consumers and corporations with traditional humanitarian actors such as NGOs, IGOs, and states [

1] (p. 70). There is a considerable material impact of the model since sources for supporting humanitarian causes with both monetary contributions and in-kind donations are being expanded.

While NGOs have been studied for their representations of charity and activism [

8,

9,

10], the sources of the symbolic value of “humanitarian imaginaries” is also being expanded, forcing us to think about how companies impart ideas about the role of the consumer in helping. Today, the arenas of consumerism, movies, and social media must be considered for how they shape public perceptions around charitable donations, support for international NGOs, public policy, overseas development aid, and global solidarity [

11]. The ad campaigns of CRM companies contribute to this perception by encouraging consumers to get involved through the marketplace—by making a purchase, learning more about the brand, or volunteering. The companies also provide social media platforms for consumers to build loyalty as “fans”, sharing their own images as they interact with the product. I deepen thinking around the symbolic value of CRM by focusing on the B1G1 business model whereby the commodification of the shared experience of a product that also becomes a “gift” is marketed through images and texts that reinforce an understanding of humanitarianism.

Compared to CRM models that donate a percentage of a purchase price, I maintain that the B1G1 offers the possibility of fostering a more personalized social impact, enacted by the consumer who makes a purchase that then becomes as “gift”. This relationship is heightened when the same or similar product that is sold to a consumer is given to a recipient. Business analysts find that consumer trends are skewed in support of the B1G1 model, “particularly in the millennial generation, which puts a high value on social issues” [

5] (p. 28). Here, I consider the “symbolic value” generated by B1G1 companies by exploring “social issues” through the lens of “humanitarianism”, how we help others. Whereas humanitarianism once focused on “saving lives and relieving suffering”, the term also captures institutional responses to the root causes of the suffering: development, human rights, and gender equality [

12] (pp. 6–7). Thus, humanitarianism is the sum of acts that address both the immediate and long-term needs of local and distant populations. For the most part, B1G1 companies appear to be more focused on humanitarian causes related to structural poverty rather than the complex emergencies that arise in conflict and post-conflict situations [

5] (p. 32). More recently, companies have begun to offer immediate response to refugees and disaster victims [

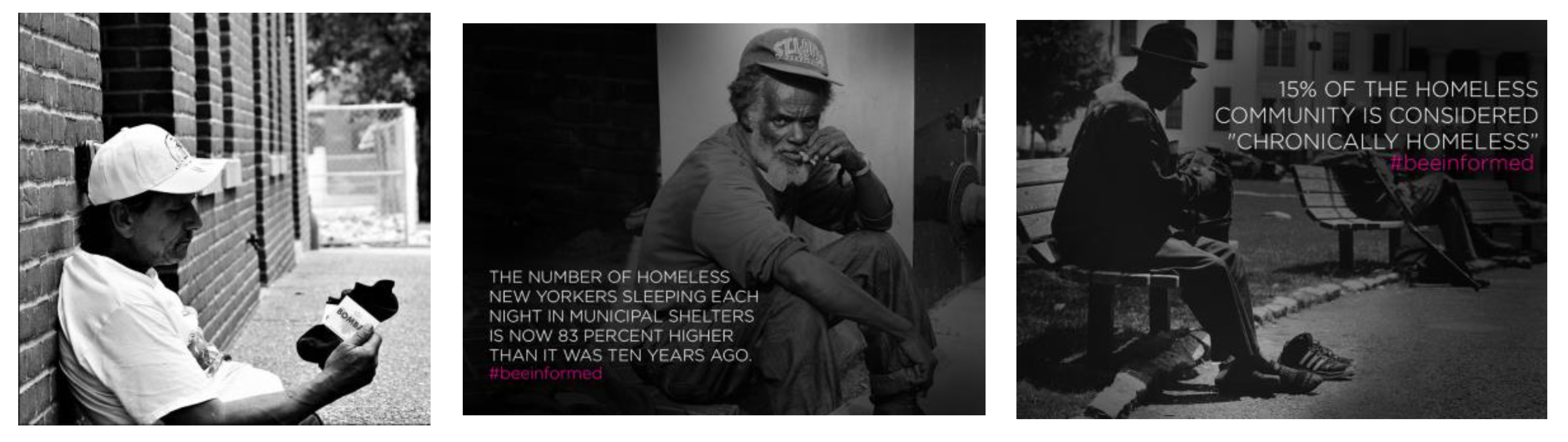

13]. The cases studied in this chapter address the effects of poverty: lack of access to education and healthcare, and homelessness.

When companies get involved in humanitarian causes by selling products for donation, the needs of marketing to increase revenue and build brand loyalty may dictate certain modes of representation. Indeed, B1G1 companies enjoy certain marketing benefits that are related to the “simplicity and tangibility of the proposition” [

5] (p. 30). As the key actor in the giving model, B1G1 companies must balance the use of the product to raise awareness while also promoting the notion of business as an effective responder to humanitarian causes. It must be noted that humanitarianism itself is a fraught terrain; as Daley points out, “humanitarian action tends to reinforce hegemonic discourse by tapping into preconceived images and stereotypes of people and (distant) places” [

14] (p. 376). The representational exigencies of B1G1 companies is readily seen in the types of products chosen for sale and donation: it is probably not surprising that the model has been most successful for consumer products, specifically apparel like accessories and jewelry. Business analysts maintain that this category of products dominates since it offers “a way for people to publicly express their unique style and personality while also providing conversations that allow them to share the buy-one give-one story with other people” [

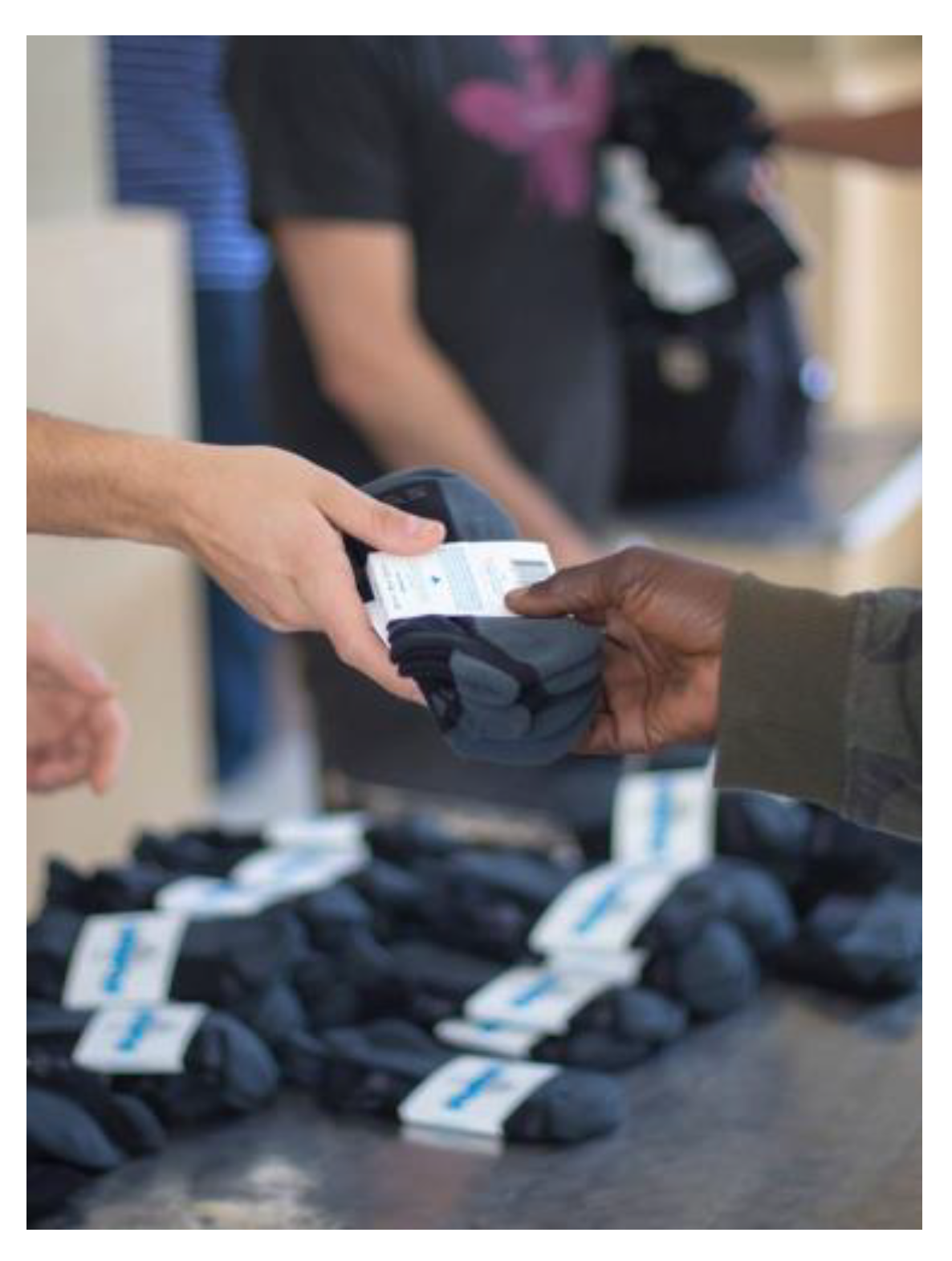

5] (p. 30). And the eagerness to share this story has given B1G1 an unusual gift in the form of free marketing, especially on social media. The visual story-telling is often enhanced with the personal encounters, organized by companies, in which consumers become volunteers and participate in “drops” to distribute aid. Further, there are some efforts to mobilize consumers, scaling up the awareness raising with events and annual days of social action. The visual story-telling of the B1G1 model, thus, contains a symbolic value as an entry point for consumers to learn about humanitarian causes and solutions, the role of business in partnership with traditional actors, and the capacity of individuals to make a difference.

2.3. The Social Marketing of Humanitarian Communication

We turn to visual analysis to see the diverse ways that B1G1 companies construct a “humanitarian imaginary” through the marketing of a similar product, linking consumers to recipients. As ways of generating meaning, images are understood as significant for provoking individual and collective action for social justice [

15] (p. 6). But any representation starts on shaky grounds of authenticity and truth; images may convey “multiple messages”, that convey “the complex or paradoxical nature of particular human experiences” [

15] (p. 3). When companies get involved in humanitarian causes by selling products for donation, marketing to increase revenue and build brand loyalty may rely on tropes about helping, the agency of the consumer as “giver”, and the figure of the needy recipient. Even the brand logo of BIGI companies can be regarded as “signs” whose visual qualities impart ideas about the corporate culture [

16] (p. 173). The exploration of the symbolic value of B1G1 campaigns through a visual analysis informed by humanitarian communication and social marketing will give us clues as to how consumers are conditioned, either individually or collectively, to think about humanitarianism with the help of the shared experience of a product.

The visual-storytelling of “helping” and “saving” often includes a cast of characters. For many human rights causes, Mutua argues that our understanding is based on the presence of three categories: savages, victims, and saviors [

17]. Humanitarianism is similarly populated with characters, with a focus on the victims and, to a lesser extent, the saviors in the form of aid workers. The absence of “savages” or perpetrators is explained by the roots of humanitarianism as an apolitical process of helping that avoids pursuing accountability for crises and human rights violations. Humanitarian communication is simply reinforcing the field’s traditional stance of neutrality and impartiality in both its visual treatment of victimhood as well as relief practices. Absent the perpetrators, political action is hard to muster nor is there a sense of the Western world’s responsibility for perpetuating local and global structures of inequality. It’s easier to focus on charity and helping. Who or what is absent in the visual story-telling of B1G1 brands will signify some of the decontextualization and simplification that inevitably takes place when dealing with the marketing of humanitarianism.

In her work on the “saviors” and “victims”, Chouliaraki regards humanitarian communication as one that “aims at establishing a strategic emotional relationship between a Western and a distant sufferer with a view to propose certain dispositions to action towards a cause” [

18] (p. 109). Chouliaraki’s work has documented changes in humanitarian communication over the past four decades; she argues that we have moved into the “post-humanitarian” age, wherein solidarity is motivated by neoliberal logics of consumption that make doing good for “others” dependent on what we do for ourselves [

19]. This suggests a type of moral agency to Northern publics that focuses on pity over political action, which is mirrored in forms of ethical consumption that enable consumers to publicly express preferences about worthy causes but doesn’t necessarily lead to political participation to address root causes of suffering. An exploration of the moral disposition intended by B1G1 businesses becomes necessary when, as Ponte and Richey argue, humanitarian causes “become so imbued with symbolic and ‘ethical’ value that they are used to market consumer goods” [

1] (p. 66). The “wearing” of B1G1 brands will broadcast our identity as a “giver”, or even “saviors”, who is consciously aware of and acting on behalf of social issues.

Moreover, in the visual story-telling of B1G1 marketing, we can see how the practice of generosity is itself commodified. But the “giving” aspect of the model, which is a major part of the appeal for an ethically minded customer, is muddled by “the underlying moral intention inherent in gift exchange” [

20]. As Marcel Mauss expounded, the act of gift-giving ensures that “the recipient puts himself in a position of dependence vis-a-vis the donor” [

21] (p. 76), a persisting feature of critiques around humanitarianism and charity. The “gift” itself—shoes, socks, or other wearable object--reveal “the idea which the recipient evokes in the imagination of the giver” [

22] (p. 2). The consumer in this case believes that the shared product will make an indelible impact on the life of the recipient, who at a distance, is in no position to challenge such notions. As contributors to the marketing of B1G1 brands by wearing the product and sharing images through social media, consumers are able to both act on and display their morality while also sending messages about what types of “gifts” are needed to address the circumstances of needy recipient communities.

Scholarship within geography and development studies on the marketing of CRM companies has already raised various representational concerns with the campaign materials that accompany humanitarian branded products. Hawkins finds that the CRM models emphasize individual consumption, the selection of favored causes as those that are “easy to market”, with “catchy slogans” that result in simplification of complex social issues [

23] (p. 1799). The humanitarian communication embedded within the CRM model brings together strange worlds, the one where the purchasing is done and the one where the victims are saved. Work by Richey on (PRODUCT) RED, one of the most famous and controversial CRM “Brand Aid” initiatives, reveals how images reinforce the consumerist hegemony latent in humanitarianism; in this case, a Western celebrity Bono partnered with iconic brands like Apple and Emporio Armani to create RED-products, a portion of whose sales would benefit the Global Fund to Fight Aids [

24]. Richey argues that the representational aspects of the RED campaigns are constructed on racial and gendered dimensions with images that “have little to teach us about the lived experiences of Africans”, the main beneficiaries of the Global Fund [

24] (p. 177). Helping distant others in this case relied on images replete with flashy celebrities, sex appeal, and “coexisting notions of familiarity and distance” [

24] (p. 175). The consumer audience is brought close to the suffering but through the glamorous mediation of Western celebrities and the sale of luxury goods.

In terms of the focus on victims as needy and worthy recipients, their representation has been studied for intended effects on audiences—either to engender fundraising or other social action—and how these effects are sustained by certain visual tropes. Campaigns are often ‘victim-oriented’ with the audience’s “focus on the distant sufferer as the object of our contemplation” [

18] (p. 110). Other common tropes when featuring victims that have come to dominant human rights and humanitarian appeals include eye contact, naked bodies, and a focus on children [

25] (p. 66). This may produce a ‘shock effect’ that turns the viewer, the potential savior, into the perpetrator, as Chouliaraki argues, producing “guilt and indignation” [

18] (p. 110). In an examination of NGO appeals, Pruce detects the prevalence of three motifs of victims—desperation, determination, and defiance--that reflect organizational mandates related to aid, advocacy, and activism [

25] (pp. 65–68). These analyses suggest that humanitarian communication might heighten the desperation on the part of the victim to arouse an emotional response. On the other hand, images that convey determination and defiance might convey a sense of agency on the part of target population, rather than simply passive “recipients” dependent on “gifts”.

The visual story-telling of B1G1 marketing must be situated in recent shifts in humanitarian communication, in thinking about how consumers are presented with or confronted by causes and vulnerable populations to raise awareness and funds, conditioned to think about their own agency, and mobilized by corporations. From a social marketing perspective, visual story-telling aims to change the behavior of a target audience that will rely on B1G1 schemes to act on their moral impulses to help. Through images and texts, the brand conveys its message “in an effort to drive emotions and encourage a particular action” [

26]. In this case, consumers build brand loyalty while also learning to rely on business to address (but not solve) vexing social issues.

The next section will explore how the visual materials of B1G1 campaigns constitute “humanitarian imaginaries”. I compare the original B1G1 company, TOMS Shoes, to a recent arrival, Bombas Socks, to see how they exhibit diverse approaches. Both TOMS and Bombas Socks are United States based B1G1 companies that offer products for sale that trigger donations to vulnerable populations, either in the US or across the world. For each case, I conducted a content analysis of the ecommerce website and social media platforms (facebook and twitter), where most of the marketing material can be found. TOMS reportedly has no marketing budget nor does it participate in traditional advertising, choosing instead to use viral marketing and social marketing [

27]. I provide the mission statement and relevant background on the company. Then I used screenshot and the software Snagit from TechSmith (Okemos, MI, USA) to collect images representative of the marketing campaigns. While I focus on visuals, I also pay attention to text provided with images (if any) and hashtags featured on social media. I argue that B1G1 companies build a distinctive “humanitarian imaginary” through this visual story-telling to convince consumers to make purchases at a higher price point as a form of social action. Visual coherence across images in terms of the staging, models, and positioning will offer clues as to how companies engage consumers and new audiences in humanitarianism. I find that the different approaches are based on the type of products for sale and donation, the causes, and the proximity to the needy population.