1. Introduction

Some pictures tell stories, some constitute important symbols, some illustrate, some heal. In the context of the complex teaching method of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis (30 July 1898, Vienna—9 October 1944, Auschwitz), one of the most versatile and undeservingly understudied avant-garde artists, thinkers, and progressive art teachers of the interwar period in Central Europe, all these aspects of imagery and image making unite in serving one higher goal: creative, intellectual, and emotional empowerment, or, to term it more accurately within the framework of our research, resilience (see

Section 2).

Promoting an interdisciplinary approach to images from the angle of social pedagogy, psychology, and art history, this study focuses on visual expression not only as a mere product of imagination, but rather a tangible residue of creative processes triggered and sustained by carefully chosen stimuli whose aim it is to open up a source of undisturbed energy sensitively channeled and steered towards obtaining maximum positive results in cognitive learning, development of emotional intelligence, fostering collective values by the means of collaboration and sharing, and offering an adequate space for creativity and self-expression.

Striving for “learning from the Holocaust” [

1,

2], this paper outlines Friedl Dicker-Brandeis’ life and artistic journey, her pedagogical method, and her role as an art teacher and “resilience tutor” [

3]. Despite the fact that art teaching was integral part of Friedl’s entire professional career, this study focuses mainly on the last seventeen months of her life in the course of which she dedicated all her energy and talent to organizing art classes in a Nazi concentration camp known as the Terezín (Theresienstadt) ghetto. The legacy which she and her students left behind and from which the present study mainly draws its inspiration—the collection of Terezín children’s drawings since 1945 preserved at the Jewish Museum in Prague as the world’s largest collection of children’s creativity from the period of the Shoah—is thus an invaluable authentic source for positive learning from one of the biggest tragedies in human history.

2. Resilience, Resilience Tutors and Art

The construct of resilience deals with the question of how individual become human persons, not despite but through their “wounds”, and how it is possible to go through painful life situations, turning them into creative resources [

4] and discovering the “ordinary magic” [

5]. Resilience has been defined as “a class of phenomena characterized by good outcomes in spite of serious threats to adaptation or development” [

5] (p. 228) and as a range of processes, and not an individual trait, involving man mechanisms [

6]. Besides the nuances stressed by each of the possible definitions, the key understanding of resilience is that it can be considered both in terms of a product (the well-being against all the odds) and as a process (the path to face adversity). Furthermore, it is crucial to refer to the human ecology [

7,

8] where this process occurs, considering systems and relationships within the special and temporal dimension, in order to take into account one’s personal response to challenges and proximal help to face them, but also social commitment to change the condition leading to disadvantage [

9]. Resilience involves both the capacity of people to find resources (psychological, social, cultural, and physical) sustaining their life, and the capacity to negotiate the meaning according to the context and culture(s) for these resources to be provided [

10].

The understanding of “protective factors” [

11] fostering resilience is of utmost importance for professionals (social workers, educators, psychologists, therapists etc.) whose goal is facilitating identity development processes within different contexts. In this study, we focus particularly on the role of the resilience tutor [

3], a significant other that is able to commit him/herself to taking care of children, fostering their development, and promoting the process of narrating one’s own story and searching for meaning. Every traumatic experience can be seen and processed in terms of “suffering what is going on” and “suffering what internally one represents about what happened” [

12]. Hence, allowing the other to tell his/her story and to listen to it, the resilience tutor offers a chance to negotiate new meanings that connect personal and social representation, as well as to and process new ways to face challenges and to live. Among the different media people may choose to “tell their story”, artistic language is particularly suitable because it fosters the state which Paul Ricoeur would describe as “discovering by creating and creating by discovering” that plays a critical role in coping with personal crisis and challenges [

13]. Through art individuals and groups can process their experience searching for the “beauty” (aesthetic empathy [

14]), divulging and freeing emotions in a communicable way [

3] with a twofold affinity: that with one’s self through a personal dimension (intra-subjectivity/intrapsychic) and that with others (inter-subjectivity/social) [

15]. Furthermore, the resilience tutor can be seen as a “resilient therapist” [

16]: the intervention aims not simply at instilling resilience in children, but it is configured as resilient in its core. This perspective draws the attention also to the identity of the “tutor” and his/her connection with resilient paths.

2.1. Resilience and the Shoah

Since the end of WW2, researchers and clinicians have produced a copious number of studies on the aftermath of Shoah experiences, primarily focusing on the pathological aspects linked to traumatic experiences and therapeutic strategies to provide for help, and only more recently drawing the attention to survivor resilient paths [

17,

18]. Besides this rather late turn towards resilience in this context it needs to be taken into consideration that the majority of survivors never received a formal treatment of any kind, having to rely on finding their own way or method to adjust, leveraging on their personal strengths and the support of their relational network [

19]. What might have significantly deepened the children’s ability to become and remain resilient during and after the Shoah were mainly the following parameters:

pre-trauma parameters [

20] (a “cultural capital” anchored in European tradition and in some notion of Jewish identity [

21,

22] reinforced by the “good beginnings” that the children had a chance to experience in their pre-war family life);

trans-trauma parameters (informal care givers found in friends, relatives, or even in complete strangers looking after children in hiding [

23], professional educators, such as the teacher and pediatrician Janus Korczak [

24], peer friendships [

25]).

2.2. Reform Pedagogy and Children’s Creativity

The movement of educational renewal started approximately at the end of the 19th century and was rooted in the field Rousseau’s pedagogy and his idea to place the child and the child’s needs at the center of the education, not to treat him/her as an adult to be but as “the father of the man”, according to Montessori’s thought [

26]. The new and growing attention to childhood as a value had an important anthropological impact on the society, in terms of searching for spontaneity, liberty, and originality, that affected the society and its cultural framework (pedagogy, psychoanalysis, art in its different forms, literature etc.) [

27]. The Reform Pedagogy [

28] is a result of this movement. It seeks to help children develop their individuality and be responsible for their own thought and action. In other words, it aims to encourage autonomous learning and discovery through the independent decision on the use of materials or the type of activities. Within this child-oriented system, the center of educational thinking is not the school as an institution with its rules, demands, and the supremacy of adults, but children and their development. Consequently, the focus is placed on the manner in which the school fosters children’s development, encouraging their interest and stimulating their learning capacities through the use of materials, furniture, and tools, while keeping the role of adults and educational methods within the confines of facilitation (see the Pedagogy of Steiner, Dewey, Makarenko, Montessori, Plan). Parallel to the progressive streams in pedagogy is a growing interest in children’s creativity and visual expression materializing itself in the wide-spread modernists’ recognition of aesthetic qualities of children’s drawings [

29] as well as their appreciation for what was then called “Primitive art.” Before putting down its roots at the Bauhaus and other progressive art schools of the period, the art teaching experiment was promoted by individual educators. One of them was Franz Čížek [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34], the founder of the famous Youth Class at the Viennese Academy of Decorative Arts who also initially inspired Friedl’s interest in children’s drawings. Čížek emphasized the necessity to minimize the influence of the teacher while supporting the child’s freedom of creative expression that can only grow when the children are spontaneously working from their imagination and not just following the strict directives imposed on them by an adult. While the avant-garde artists took a huge amount of inspiration in children’s creativity, they also “paid back to the system” by designing toys, furniture, and whole learning environments (such as kindergartens and schools) that helped stimulate children’s imagination and supported their innate creative instincts. Without much exaggeration it can be said that it was the artists who promoted the new vision on childhood, linking it to John Ruskin’s theory of Innocent eye, before of what psychologists later did in the new field of child psychology [

35,

36].

3. Children in Terezín

Terezín (or as it is referred to in German of the period, Ghetto Theresienstadt) was a transit concentration camp through which, during its four-year existence passed, almost 140,000 Bohemian, Moravian, Austrian, German, Dutch, and Danish Jews. The Nazis had created in the fall of 1941, initially for the Jews from the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia, however, very soon they started to use it within the framework of their evolving propaganda also as a so-called

Prominentenlager (a camp for prominent Jews from the

Reichsgebiet—former Austria and Germany—as well as the occupied Netherlands and Denmark). It was not a place that one would automatically connect with an idea of a bearable life, let alone artistic production or education. Yet, the ghetto’s

Zwangsgemeinschaft (coerced community) [

37] evolved quite spontaneously and rapidly into a center in which culture and education became the main instruments of active resistance to the point that

ex post facto it was analyzed even within the specific terms of an artistic colony [

38] or a university [

39].

The first eight months of the ghetto’s existence were marked by a severe prison regime with the strict gender separation, curfews, and the prohibition of free movement within the town walls. Already at this stage attempts had been made by those who later became the leaders of the Council of Elders (Ältestenrat) and especially its Youth Care Department (Jugendfürsorge) to separate children from adults and thus secure protected space that could be also used for some sort of improvised teaching and other children’s activities. This situation has changed after the Nazis moved out the last civil inhabitants of Terezín to other locales in the Protectorate, turning the entire 18th-century military fortress into a ghetto with its own Jewish self-government (Selbstverwaltung). Even though the Jewish representatives in the ghetto had no real decision power and all of their doings were strictly subdued to the Nazi authorities, they could, within the limited scope of their purported autonomy, organize the life of the ghetto inmates, including the creation of the Cultural Department (Freizeithgestalltung) and, little by little, also a system of separate housing for children (Kinder- and Jugendheime). First, still in July 1942, opened a home for Czech speaking boys (L 417) and, in the fall of the same year, it was followed by a girls’ home (L 410), a home for German speaking children and youth (L 414), and other facilities for younger children and infants as well as homes for the youth over 15 years of age.

Although it was strictly forbidden to provide any formal education to the ghetto’s children and thus all attempts for educational activities had to remain secret, drawing, singing, and theater, considered an innocuous pastime by the Nazis, were allowed. Despite all the atrocity, this was a great opportunity for an educational experiment that would substitute the big part of the classical curriculum by creative subjects. Quite naturally, this opportunity was also used by Friedl Dicker-Brandeis as soon as she was able to adapt herself to her new situation of a ghetto inmate.

4. Friedl Dicker Brandeis: Life, Art and Art Teaching as a Strategy for Survival

Born in the fin-de-siècle Vienna on 30 July 1898, Friedl was the only child of Simon Dicker, a sales clerk in a stationary shop originally from Uzhgorod (Ungvár), and Karolina, née Fanta, descendant of a Bohemian Jewish family. Friedl was only three and a half when Karolina succumbed to a sudden heart failure. A story handed down among Friedl’s friends has it that one day, playing in a park, Friedl picked a new wife for her father. Charlotte Schön became a loving stepmother to Friedl, but her marriage with Simon was far from ideal. Charlotte’s and Simon’s frequent quarrels and the thick atmosphere in the family’s tiny apartment on Bleichergasse 18 in the 9th district of Vienna might have been the trigger instilling in Friedl the yearning for independence and seeking refuge in creativity [

40].

At the age of fifteen, she convinces her father to support her enrollment to the Viennese Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt (GLVA) to study photography, however, capturing the outside world through the lens of a camera is not what her creative heart desires. As a result, she pursues her studies simultaneously in the Textile Department at the Academy of Decorative Arts where she meets Franz Čižek (1865–1945), a fervent promoter of Reform Pedagogy and the founder of the famous Youth Art Class [

33]. It is the encounter with Čižek that inspires Friedl’s early interest in the experimental approach to artistic creation and art teaching.

After her graduation form the GLVA and after spending nearly two years under Čižek’s tutelage, Friedl finally finds what seems to be a perfect opportunity to fully develop her multifaceted talent. In 1917, she enrolls to a private school founded by a painter Johannes Itten (1888–1967), a recent graduate from the Stuttgart Academy of Fine Arts where he studied under Adolph Hölzel (1853–1934), one of the early pioneers of abstraction adherent to the holistic approach to art.

Itten quickly wins the loyalty of his students sixteen of which decide to follow their revered teacher to the State Bauhaus when in 1919 the new director of the school, architect Walter Gropius (1883–1969), offers him a teaching position in Weimar. Among the members of the “Itten hardcore circle” are also Friedl and her closest friends and future collaborators: Franz Singer (1896–1953), Anny Wotitz-Moller (1900–1945), Margit Téry-Adler (1892–1977), Naum Slutzky (1894–1965), Max Bronstein (1896–1992, later known as Mordecai Ardon), and Franz Skala (1892–1975) [

41].

The Bauhaus years are very fruitful and rich in terms of gaining experience and forming future professional partnerships as well as close personal ties. Besides Itten’s Vorkurs (preparatory course, a fundamental training to form a complex visual language based on the Kontrastlehre—the theory of contrasts—that Itten himself adopted from his teacher Adolf Hölzel in his Stuttgart years), Friedl gets inspired by other artists teaching at the Bauhaus: Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), Paul Klee (1879–1940), Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956), Oskar Schlemmer (1888–1943), Georg Muche (1895–1987), Ludwig Hisrchfeld-Mack (1893–1965), and Itten’s close friend and collaborator exploring the cross-fertilization of music, painting, and movement Gertrude Grunow (1870–1944). While still at the Bauhaus, Friedl and Franz Singer also work on their first collaborative designs for theater in which work they continue also upon leaving the school and founding their first own Berlin-based studio prosaically named Werkstätten bildender Kunst.

Life in the metropolis is exhausting. As Friedl writes in one of her letters to Anny Wotitz: “I don’t think I can stay put much longer. What I lack here, as anywhere else, is money without which it’s difficult to achieve anything ...” [

42]. In 1924, she returns from Berlin to Vienna. First, she shares a studio with Anny Wotitz, later works together with Martha Döberl, designing decorative textiles, laces, leather accessories, and book bindings. In 1926, Franz Singer relocates to Vienna and, once again, joins forces with Friedl. This time they create a studio for interior design and architecture which soon becomes known as Atelier Singer-Dicker. They are working on commission for many private clients, renovating and refurbishing residential villas and apartments. Besides their work for private proprietors, they also engage in municipal projects that are part of an ambitious urban planning of what is known as Red Vienna. In one of the

Gemeindebauten (communal houses) called Goethehof they design a Montessori kindergarten which opens its doors to first students in 1930. At this point, Friedl immerses herself again in children’s world, rethinking the parameters of an optimal space and interior design that would stimulate a healthy development of the child and that would meet the requirements of progressive education fostering learning through collaboration, shared values, and creativity [

43].

Meanwhile, the political situation in Austria is worsening, inclining more and more towards chauvinist conservatism described as Austrofascism. Friedl becomes more politically involved, engaging herself in clandestine activities of the Austrian Communist Party (KPÖ). Her political engagement finally brings her twice to prison—first in December 1931 and later in September 1932. Since then it becomes clear that she cannot stay in Austria and, quite naturally, when seeking a refuge, she chooses Prague, the hometown of her late mother.

In the Czechoslovak capital, Friedl has a status of a refugee, however, thanks to her family ties she is able to escape the squalor of the collective housing organized for German and Austrian refugees by several relief committees, and maintains her own studio on Jaromírova Street near the railway tracks under the Vyšehrad Hill. Here she gives private lessons to a handful of her students among whom Edith Kramer (1916–2014), who after her graduation from the progressive Viennese Schwarzwaldschule had followed Friedl to Prague from Vienna, is the most talented. Besides giving private lessons, Friedl also becomes involved in teaching children in refugee shelters and maintains contacts with her old Viennese acquaintances—psychoanalysts who, like herself, are seeking a temporary refuge in Czechoslovakia. She becomes particularly close to Annie Reich (1902–1971), the ex-wife of the psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich (1897–1957), who analyzes Friedl and shares with her a genuine interest in child’s psychology.

Friedl’s situation in the new country becomes more secure in March 1936 through the marriage to her first cousin, Pavel Brandeis (1905–1971). For a moment, life seems to be bearable again, however, this situation does not last for a very long time. Prague gets literally flooded by another massive wave of refugees from the Sudetenland which Czechoslovakia loses to the German Reich after the signing of the Munich Treaty on 30 September 1938. While many of Friedl’s friends are heading overseas or for the Mandate Palestine, Friedl herself turns every proposition for obtaining an immigration visa down.

Finally, she and Pavel decide to move to the countryside, a little town called Hronov in Pavel’s native Eastern Bohemia. Pavel gets a job there as an accountant for the Spiegler textile factory for which Friedl occasionally works as a designer. Life in the country is new to Friedl and, despite the worsening conditions that the Jews have to cope with since the Nazi occupation of the rest of the country and the proclamation of the Protectorate, she describes it almost as an Arcadia where she is finally able to calm down, read, think, draw, and wander around with her sketchbook and a little terrier Julenka. To maintain contact with her closest friends, who also occasionally come to visit, she writes letters into which she incorporates her reflections on art and art education triggered by her extensive reading and the plenty amount of time that she has on her hands. As everything else, however, even this relatively uneventful four-year Hronov period comes to an abrupt end. In the mid of December 1942 Friedl and Pavel receive a call-up notice to report themselves for deportation to the Terezín ghetto to which they arrive on 17 December 1942.

4.1. Teaching Art in Terezin

Friedl comes to Terezín as a mature artist and an experienced teacher at the moment when the system of children’s homes is already established by the Youth Care Department. Although there are constant serious problems (the scarcity of food, the lack of pharmaceuticals, epidemics, cold, and bad hygienic conditions, let alone the massive scale of suppressed traumas resulting, inter alia, in increasing apathy, moral compromises, etc.), surprisingly, or perhaps just because of it, a huge amount of attention and energy is dedicated to cultural production and, first and foremost, to children’s and youth education which needs to be organized in a clandestine manner. As Dr. Gertrude Bäuml, a psychologist and Friedl’s close collaborator in Terezín puts it, the entire work of educators in the ghetto “takes place under the sign of ‘despite’” (“Unsere gesamte Arbeit in Theresienstadt steht unter der Devise ‘Trotzdem’”) [

34]. In that sense, Friedl comes to the ghetto in the right moment, as her creative approach to teaching and natural proneness to experiment is what is sorely needed under the detrimental conditions in which everything needs to be performed with not much planning, instantaneously, often improvised, and with minimal means.

As soon as she adapts herself to her new situation, Friedl is given an opportunity to move into the girls’ dorms at L 410 and, at some point in March or the beginning of April 1943, she starts teaching art and she will do it until her deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau on 6 October 1944, remaining very active and almost exclusively devoted to what she thought was her mission. Running her program, she gathers all kinds of material usable as art supplies, sorting, evaluating, and further examining the drawings collected in her classes, and, together with her young students, designing costumes and sets for children’s theatrical performances.

As she articulates it in her notes for a presentation of her pedagogical work on the occasion of the children’s drawings exhibition that takes place in the basement of L 410 in July 1943, “art lessons are not intended to turn all children into artists, but aim to unlock and sustain their own creativity and independence as a source of energy, to stimulate their fantasy, strengthen their critical capacity of judgment, and their observation talent” [

44].

She realizes full well that what the children in the Terezín ghetto need in the first place is not just some dull exercise or a soothing therapy, but a complex care that would provide the right stimuli and support for the development of both their intellectual and emotional capacities. Bearing that in mind, she is ready to use the method that she herself experienced as a student with her teachers at the Bauhaus, adapting it for the sake of children that are not aspiring professional artists, but, both as a group and individually, a great pool of energy and talent with huge receptive and imaginative capacity that should not be wasted but rather transformed to a positive force through the means of creativity. At the same time, quite in the vein of Čížek’s pedagogical principles, she recognizes the importance of minimizing the teacher’s influence and restraining his/her role to that of a facilitator, interlocutor, and, if needed, a moderator of the collaboration among the students themselves. In her notes, she comments on this as follows: “The teacher should abstain from imparting any possible influence onto the child, including the showing of his/her predilection for certain taste or artistic qualities found in the child’s expressive strength and naïveté, for this might lock the child on a certain primitive level or to push him/her towards a cliché of various isms or the serious academic drawing [

44].

Eventually, when stressing the necessity of undisturbed though well-supported development of child’s creativity, Friedl touches upon the sensitive, yet very important issue of what she defines as the “aesthetic influence of the parental house.” What she means by it is a specific set of preconceived aesthetic norms which parents impart onto their children as a firm canon of “beauty” that is constituting and solidifying the children’s conformity with all sorts of conventions, aesthetic or otherwise. As Friedl emphasizes, this represents a major hindrance to the development of the child’s critical thinking, creativity, independence, and higher positive values. She writes: “Even here [in Terezín] the uncritically adopted, meaningless, and vapid ‘beauty’ of Makart’s Snow White continues to haunt us. Everything that opposes the final product, even at the price of temporarily giving up rich forms in favor of hitherto unexperienced beauty, all of that is a tremendous help in our classes. Critical distance from the aesthetic influence of the parental house can be achieved through [the analysis of] folk art, primitive art, modern painting and sculpture, as well as through one’s own understanding of Old Masters” [

44].

4.2. The Inner Image: Analysis of Old Masters and Studies in Themes

The analysis of Old Masters (

Anlyse der Alten Meister) is the cornerstone of Itten’s preparatory course inspired by his own teacher Adolf Hölzel. Unlike the elementary etudes such as rhythmical exercises (

Rhytmische Übungen), chiaroscuro studies (

hell-dunkel Studien), exercises based on the theory of color (

Farbenlehre), and studies in texture (

Materialstudien) and form (

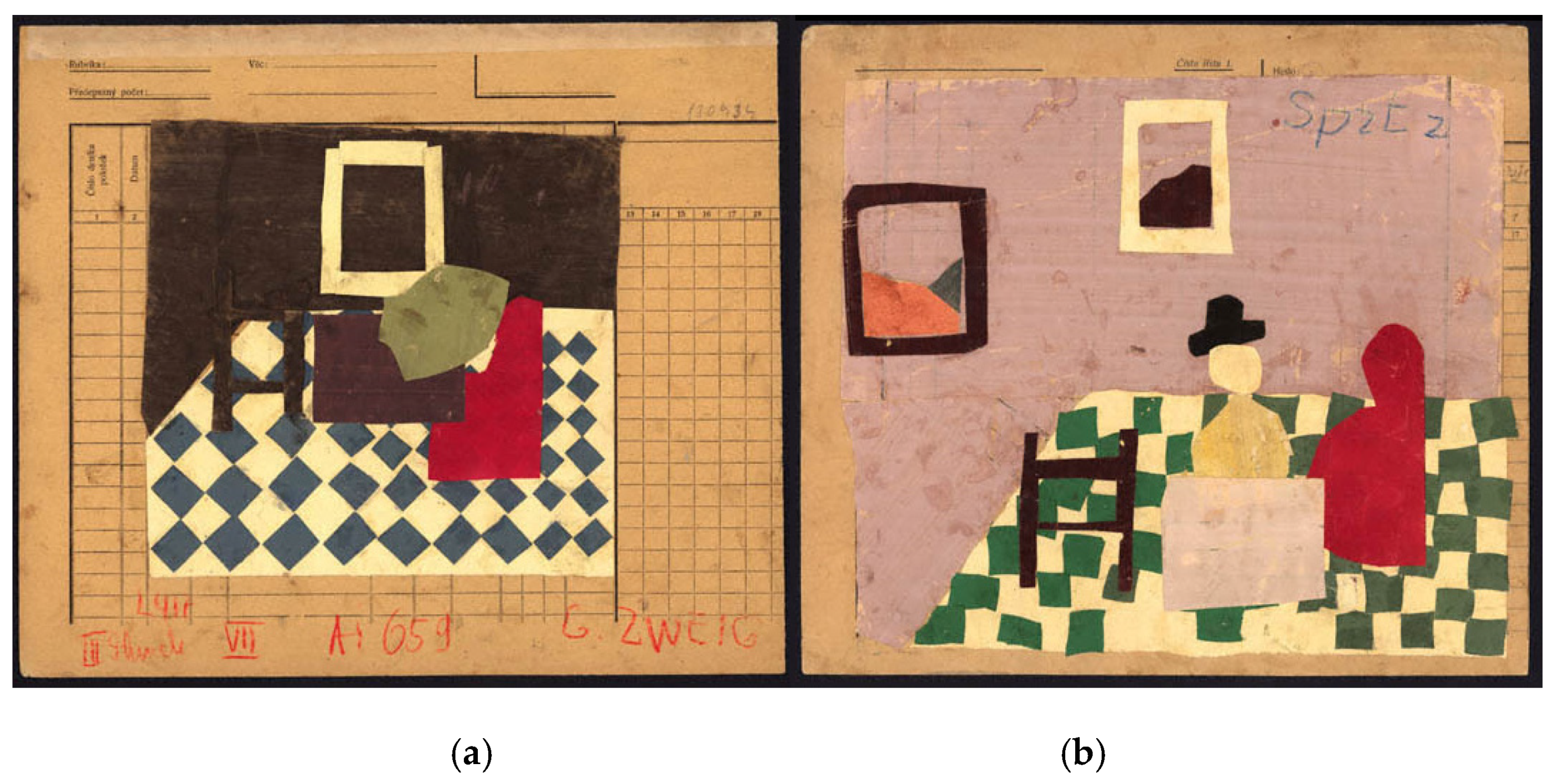

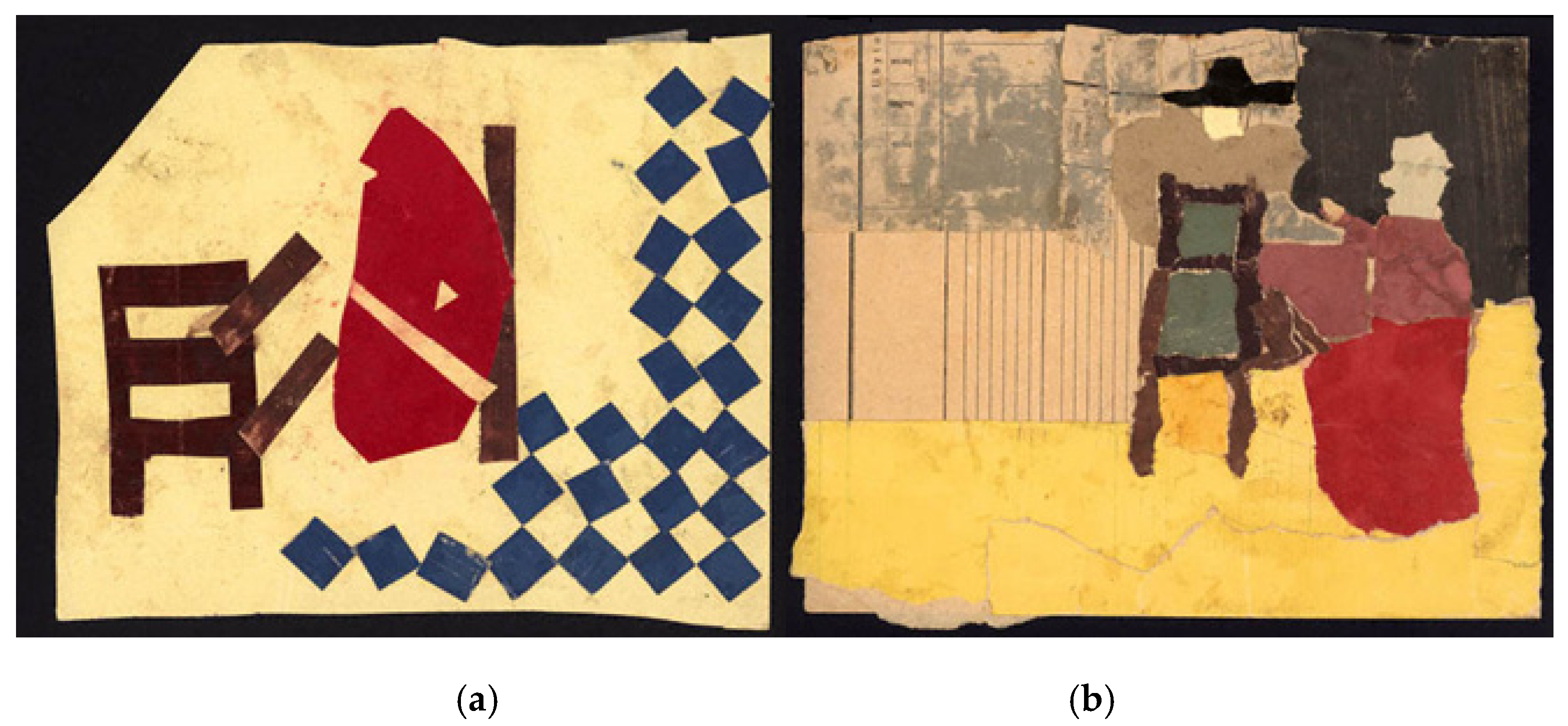

Formlehre), this type of exercise is much more complex. It is a synthesis requiring a certain degree of maturity and freedom in employing the entire repertoire of the elements of graphic expression, as well as the use of color and spatial composition principles. At the same time, it is an exercise that stimulates the use of quick visual reading, memory, and the ability to capture the gist of a structure in one’s own manner by penetrating the surface of things instead of relying on a mere imitation of their external appearance. Such deeply analytical approach to images based on an intuitive deconstruction of classical patterns through one’s own creative imaging is a great tool for cultivating the synchronicity of the eye, hand, and mind and it also contributes to the strengthening of self-confidence by providing the creators with the opportunity to test their own capacity to freely express, narrate, and perform their own valid interpretation of what is traditionally viewed as an icon by disposing themselves of the notion of its untouchability. Four collages based on a reproduction of Jan Vermeer van Delft’s

The Glass of Wine that were completed in Terezín under Friedl’s guidance (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) are a practical demonstration of the exercise and what various results it may yield, especially when assigned to children not yet overwhelmed by cultural clichés and false reverence. Whereas for adults the iconic masterpiece may assert its authority primarily through its generally recognized value (historical, aesthetic, artistic, financial), children cannot truly appreciate it until they understand its language. Without the possibility of reading into a given image through the appropriation of its basic organizing principles seen as a natural extension of the real world, that given image is but a mere decorative ornament devoid of any concrete meaning and, more importantly, ripped out of the context of universal values underpinning the child’s orientation in the world.

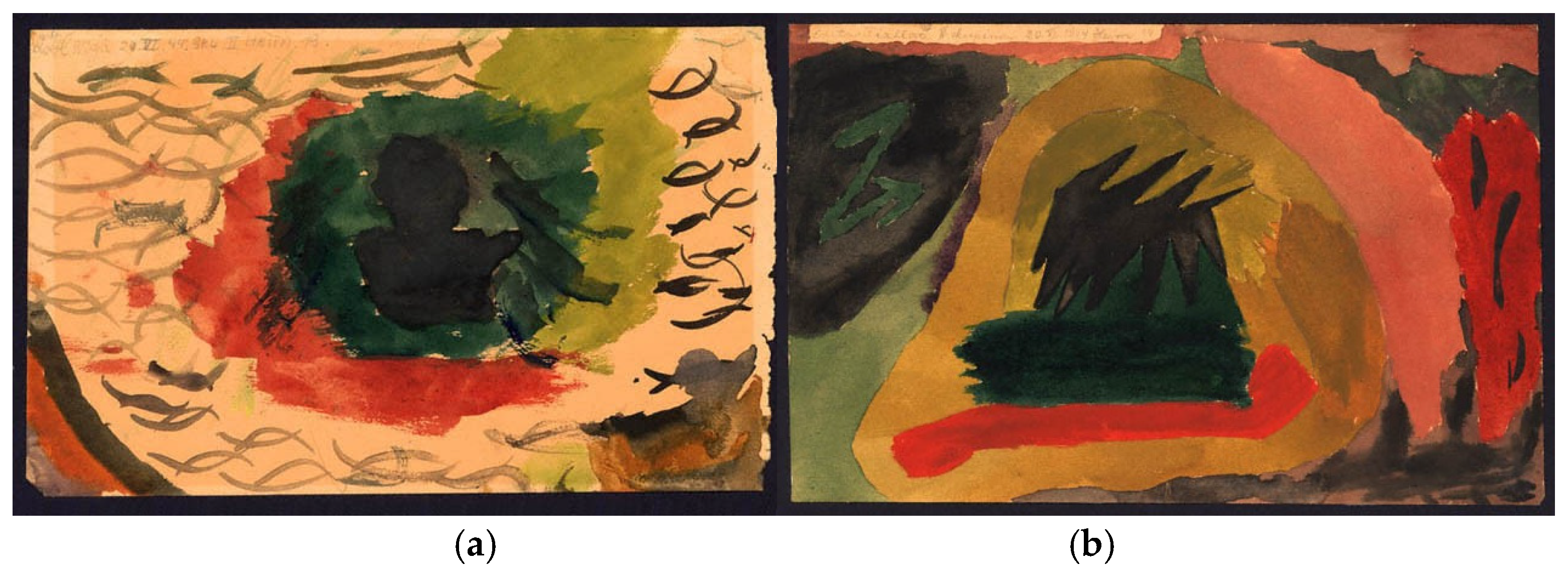

How the same principle works in reverse, that is when the child is not given an image to deconstruct but instead is asked to construct a new pictorial reality following his/her own “inner image” of a given theme, can be demonstrated on two watercolors originating from the same class that took place on 20 June 1944 (

Figure 3). While one of them (

Figure 3b), completed by a 13-year old girl, is a more clichéd and aestheticized visual elaboration on the theme of fear or a stormy atmosphere that is relying on the expressive use of dark colors and a universal symbol of a lightning bolt, the other (

Figure 3a), completed by an 11-year old, is a much more inventive, bold figurative composition vaguely resembling a dark silhouette of a man drowning in a lake. The explanation on the verso of the drawing recorded by Friedl and based on a conversation with her student reveals that behind the abstract notion of fear or a dark, stormy, threatening atmosphere there is a very concrete anxiety expressing narrative that facilitates the reading of the composition’s individual elements: “

Ein gefangener Mann,

rundherum Schatten,

die Striche sind die Gitterstäbe des Gefängnisses.” (A man in a prison surrounded by shadows, the strokes represent the prison bars).

4.3. Friedl’s Followers

The most important among the “followers” who drew direct inspiration from Friedl’s pedagogical work was Friedl’s former student and assistant Edith Kramer (1916–2014). When she managed to escape to the United States in 1938, Edith carried on Friedl’s legacy incorporating it into the newly developing field of art therapy. She was among the first to promote art as an effective therapeutic instrument in American educational institutions and contributed greatly, through both her teaching practice and theoretical writing, to the development of art therapy as a full-fledged, autonomous field [

45,

46]. Another important personality implementing her direct experience with Friedl’s teaching in her own work was Erna Popper-Furman (1926–2002). Erna was only 16 when she was deported to Terezín where she worked as a care giver at the young boys’ home L-318. Since Friedl was also teaching in this facility for boys from six to nine years of age, Erna attended Friedl’s classes and occasionally also assisted Friedl in her teaching. In this sessions, Erna had the opportunity to experience how Friedl recognized and promote the spontaneously unfold of the greater person within each child [

26] by reflecting and discussing with children about their drawing, and also asking the older ones to help the youngers. Erna was still in Terezín when she decided, also under the influence of Friedl, to study psychology after the war’s end. After the liberation in 1945, she first worked in one of the orphanages for repatriated children near Prague and soon after moved to England where she served as a consultant to Anna Freud. Having graduated from Freud’s Child Therapy Training Program, Erna eventually left for the United States where she became a well-known psychoanalyst specializing in children and maternity [

47].

5. Conclusions

The life and work of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis is an exquisite example of how art and resilience can work together as two complementary elements. On one hand, we may interpret Friedl’s own personal journey as one big struggle for resilience, on the other, we may see her professional career, and especially its last almost two years spent in the Terezín ghetto, as that of a resilience tutor.

Friedl knew full well that what she needed to activate, mobilize, and foster in children trapped in the harshest of conditions was their creative energy which she understood not only as a source for artistic excellence, but primarily as a driving force nurturing critical thinking, understanding, empathy, the ability to set up successful collective strategies, and the most important thing of all: the ability to cope and survive, and the possibility to live despite the necessity of having to face an oppressive and, as it turned out later, genocidal regime.

In a place overwhelmed with material scarcity and all sorts of deprivations, she was not only able to maintain a fully functional art teaching program, but she also proved to quickly adapt in turning disadvantages and limitations to a great educational tool fostering sharing, collaboration, empathy, and other positive qualities and skills to serve the ultimate goal of personal growth of an individual for the sake of the growth of the entire group and vice versa. In this sense, she understood visual expression not as a goal-oriented production of images, but as a truly creative and restorative process in which the path is the goal in itself, a path where she helped children in bridging the “culture of the ghetto” to the “culture of their origins” and in negotiating meanings for their present and their future life. Seen from that perspective, working on an image, be it an individual or a collaborative enterprise, is a creation of a self-sustaining reality that is governed exclusively by principles defined by the work’s creators. In the context of the Terezín ghetto this had a special meaning, for the notion of the possibility to create (and very often to create something out of the virtual nothing) became a mighty instrument of empowerment. The chiaroscuro studies are an instructive example of a possibility to create an entire world only by means of black and white crayons or paint, the collages are a practical demonstration of how with the use of tiny bits of discarded and carefully rationed paper one can still give his/her phantasy a clear shape and bright color, etc.

For all that has been mentioned in this text, Friedl can be eventually seen as a pioneer in the field of art therapy, promoted and further developed by some of her students in the post-war period. She can be a role model for art teachers, yet her legacy can also serve as a great source of inspiration for educators and social workers specialized in the child’s development and resilience. With regard to the regular school curriculum structure, Friedl’s teaching experiment demonstrates the indisputable importance of creative subjects for improving the quality of cognitive learning and the capacity of imaginative and critical thinking that can be applied equally in the realm of artistic creation as well as outside of any aesthetic context whatsoever. Furthermore, her story seems to be particular apt to work with children on the topic of the Holocaust from a multidisciplinary approach connecting history, biographies, art, children’s creativity, and child’s rights. Last, this partial study confirms that the legacy Friedl and her children left behind in the collection preserved at the Jewish Museum in Prague, requires to be more studied and spread around as a source for art learning, as well as a source for promoting the intentional use of creativity and for the understanding of human development in education and social professions.