1. Introduction

In November 1747, were celebrated the solemn celebrations for the Filippo’s birth of Philip, the firstborn of Charles of Bourbon and Amalia of Saxony, born after five females, of whom three disappeared prematurely. This event is described in the volume entitled the

Narrazione delle solenni Reali Feste fatte celebrare in Napoli da sua Maestà il Re delle Due Sicilie Carlo Infante di Spagna,

Duca di Parma,

Piacenza &c. &c. per la nascita del suo primogenito Filippo Real Principe delle Due Sicilie [

1] (frontispiece), published in Rome in 1749.

The solemn celebrations celebrate the long-awaited monarchical stability with the birth of Prince Philip and they give back an ‛image ‘of the city of Naples which, during the ‘700 was the destination

of the better Italian and foreign nobility that from [...]

more remote countries they went to admire the pump of these shows [

1] (p. 4–5). In this sense, this episode can be placed in the broadest panorama for the creation of ephemeral apparatus that was widely used in ‘700 Neapolitan [

2].

On this occasion, the King ordered that in Naples occurred sumptuous celebrations which be worthy of not less than his greatness, than the magnificence of that metropolis, and the splendor of his subjects [

1] (p. 4). And so, from November 4, for two consecutive weeks, sumptuous events such as masked dancing parties, banquets, serenades and games were held, which more architectural spaces as the Royal Palace with the annex Largo di Palazzo, the Real Theater of San Carlo, Castel Nuovo and Largo di Castello [

3].

The drawings of the theatrical machines set up in these spaces are included in the

Narrazione and are the work of the set-designer Vincenzo Re (1695–1762), assistant of Pietro Righini at the Real Theater of San Carlo and who will replace his from 1740 [

4] (p. 247).

The

Narrazione is divided into two parts. The first part (about one-third of the volume) is the subject of the literal festivities description, anticipated by the detailed exhibition of the celebrations program, divided into fifteen days including date, event and place. This program is returned here with a synthesis image in the form of brochures or flyers drawing by writers (

Figure 1). In the activities program are also planned rest days, Tuesday and Friday. This specific choice alludes to another image of the city of Naples, this time of the conceptual type and linked to the spirituality and superstition which according to an old popular saying, in Venus and Mars they don’t marry and don’t depart, and they aren’t days for beginning the Art. After the description of the events program, the

Narrazione gets into the heart of each day event description. The tale in the book completely immerses the reader in the reading, sparking an ever-arousing an increasing imagination [

5] for the accuracy and meticulousness of all the architectural, figurative and ornamental elements described: rooms staged by long golden ‘dammaschi’, on which are depicted white ornamental motifs; dames adorned with their most precious clothes, covered with gold coins and gems of great value; sparkling lights and vases of beautiful manufacturing, placed on columns from which are engraved velvet pendants that enclose mirrors of fine golden carving; etc.

But for the author of Narrazione, the mere ‘mental’ imagination induced in the reader is not enough. Every single day, even if described with details, is accompanied by drawings; ‘images’, which illustrate with a visual summary the event of that day. In this sense, the fantasy of imagination is accompanied by a series of real images or drawings.

The second part of the Narrazione (about two-thirds of the volume) is therefore exclusively made up of visual images who Vincenzo Re ‘invented’ and ‘outlined’ and who Angelo Guiducci, Giuseppe Vasi, Francesco Polanzani, Nicolas Henri Jardin and Luigi Le Lorrain engraved. These ‘images’, mentioned by the author of the Narrazione as ‘tables’ or ‘notes’, are all accompanied by a designation that shows in plant view, cross-section or perspective every space of the celebrations, always animated by the guests. The ‘images’ exhibited are: The Royal Palace spaces map (which used to set up the celebration); the Royal Palace apparatus (which served as a stage for dancing); the decorations of the Court Theater; plant, cross-section, and front of the Real Theater of San Carlo (where the masked dancing was held); the ‘Cuccagna’ and the big pyrotechnic machine (sets up, respectively, in the Largo di Palazzo and Largo di Castello).

The fact that the

Narrazione of the festivities is made up of written parts and drawn tables induces to reflect on the relationship between subjectivity and objectivity of the imagination with respect to different forms of representation of the same data [

6]. There is no doubt which the literal description can generate a multiplicity of ‘mental images’ of a subjective nature, linked to the culture and sensitivity of the reader; conversely, the ‘drawn’ image reduces the subjective effect conditioning the reader’s imagination into a description of the facts that should be more objective. However, reading the

Narrazione and comparing the written texts and drawings, there was often a certain margin of ambiguity between the richness of literary descriptions and a more synthetic graphic representation which, even though being conspicuous, does not cover the entire program of events. In this sense, the virtual reconstruction project of these spaces through the digital modeling and subsequent visualization, conducted here by the writers for the first time, has not been devoid of any further interpretations of the reported facts, both in relation to written texts and drawings which, in the form of plants, cross-sections, fronts, assonometries and perspectives, return metric, architectural and figurative information on the apparatuses of the ‘solemn festivities’.

2. The Representation of the Rooms and the Festivities Places

In the Narrazione the rich literary description is accompanied by the iconographic one and it is a guide to the knowledge of the main places used to celebrate the births of Philip, the first male son of Charles of Bourbon. In this sense, the literary work combined with visual image production are in a wider iconographic production that characterized the description and the historical representation of the ephemeral apparatus produced in the city of Naples and in the cities of its kingdom, especially in the ‘700.

The fifteen images which shows the different spaces of the festivals resume and continue the use to document the great celebrations organized by the sovereign as those for the Fair of

Real Marriage (1738) [

7] and for the celebrations of the firstborn Maria Isabella (1740) [

8], both organized by the architect Ferdinando Sanfelice.

The images contained in the

Narrazione stand out for different representation type: plants, cross-sections, accidental and central perspectives, section-perspectives. Starting an analysis of the geometric representation methods through which images are drawn, it is particularly interesting here to compare the Tavv. I and VIII, respectively the

Part of the Palace that served the festivities [

1] (pp. 28–29) and

cross-section of the Real Palace,

and the staircase which introducing into the Real Room,

the Games Rooms,

and Refreshment room [

1] (pp. 52–53), elaborated in orthogonal projection and representing in plant and section the portion of the Royal Palace used for celebrations (

Figure 2A).

The plant shows the second level of the Royal Palace, while, watching well, the altimetric cross-section corresponds, for the first level, to the ground floor (A-A’); for the second, on the first floor (B-B’). In this sense, the plan of the altimetric section is not the one but it assembles two different projections; in addition, the section plan for the first floor also has a bayonet course. This implies that the intent of the illustrator was not the correct application of the geometric method but the construction of a conceptual image capable to displaying the itinerary path for to access to the

Real Room from the entrance to the ground floor at the Royal Palace; so that in the plan (which representing the first floor) is used a graphic symbol recalled in the legend is used to indicate the entrance-hall of the ground floor (

Figure 2B).

Referring to the legend attached to the plant, the path to access the Real Room, starting from the main entrance and the courtyard (+, A) through the Royal Staircase (B), led to the first floor to enter in the Dancing Room. For the occasion was closed the usual access door (D). According to festivities organizers, the lateral position of this access (still in place) would not have induced the guests as amazed as that of a frontal access to the principal room. Therefore, was opened the door (G) between the Real Room (E) and the Anteroom (H), with access, the latter, from the next door (K). Through a passage (L), near the wall of the theater (F) had access to the rooms for sweets and refreshments (N, O).

A large group of images is built using the perspective. The central perspective is used for the representation of the room in the Royal Palace, while for urban views, the accidental perspective, except for the Cuccagna, is also displayed in central perspective. The reasons seem attributable to the specific nature of the different character of the depicted space. Indeed, where there are bilateral symmetry systems (the Dance Room and the Cockaigne apparatus), this spatial configuration is reinforced using the central perspective. In the case of urban contexts which are articulated in their space, however, the accidental perspective is used.

Specifically, the central perspective images which show the dance room in a longitudinal direction are Tavv. II, III and V:

First Parade Dancing [

1] (pp. 32–33), facing to the access door (

Figure 3A);

The Dance in Mask [

1] (pp. 36–37), towards the theater scene (

Figure 3B);

Dance Room sets up for the Serenade, still towards the theater scene but adorned in different way so as to cause remarkable amazement in the guests (

Figure 3C). The

Serenade, entitled

The Dream of Olimpia, was accompanied by a

Choir of Musicians and the drawing of the theatrical scene that served as a background for serenade is represented in Table VI of the

Narrazione.

All the images of this room give the magnificence of the work by Vincenzo Re, real stage designer of the Real Theater of San Carlo. The room walls were covered by long

golden dags alternated with white drapery strips and

flowers of various shapes, which (the author notes) thanks to their perfect arrangement seemed like composite pillars. Above the capitals were large vases, and in the center, there were huge mirrors all

surrounded by fine golden carvings. After dancing in the celebrated in the room, the participants could rest with sumptuous banquets prepared in the adjacent rooms. The choice to make two views for the same room has a dual purpose. They wanted to highlight not only the architectural elements and the rich scenery that surrounded it, but above all the most significant points of view. The first image places in the center the presence of the majesty with three large decorated chairs (

Figure 3A). The second, however, shows like stage scenery, a staging by

amphitheater shape, accessible through a large staircase, on which were the bigger musicians of

any possible instrument dressed in pink and turquoise and garnished with elements of silver; above them was an enormous velvet drawer with gold embroideries (

Figure 3B).

Illumination was another significant project component: huge crystal luminaires; perimeter walls supporting small lit torches; golden mirrors that reflected the light, helping to create a floating atmosphere; lumens arranged neatly that

did not produce any confusion,

but they well pleased the view of the guests [

1] (p. 7). This bright image was so impressive that it was imprinted in the memories of the participants to the point that this event was remembered as that of the ‘sparkling hall’.

Another place used to celebrate the festivities was the Real Theater of San Carlo, inaugurated by the same King ten years ago and where was replicated on Thursday 9th the Serenade, which had taken place a few days earlier in the Royal Palace Room. This event was in fact very successful so that the King wanted to replicate it in his Royal Theater, providing his free access.

The events described were repeated on alternate days until the 18th day when the Real Theater of San Carlo was organized as the predominant event of all the solemn festivals, the most sumptuous and splendid event ever seen or the Great Dance Character Party or in Mask. On this occasion, the theater was divided into two parts: in one there were the knights and dames of nobility; in the other, the people took part.

This event organized in the Theater of San Carlo also became part of the collective Parthenopean imagery. For the evening of the 18th there was a great even more outstanding scene of the Theater itself. Huge wooden bows were surmounted by enormous velvety drapes that contained, for three rows in height and three in width, the audience’s platform. Between an arch and another there were pillars, which had the same size of the same platform. At the top there were enormous mirrors, and enormous ‛lumiere’ were placed along the same pillars. The theater on this occasion was illuminated as the light of day. With this narration, the author gives imagines of the evocative atmosphere created by the blend of all these reflective elements (mirrors, golden carvings, lumiere, candles, jewels, precious stones).

For the representation of the images which shown the Real Theater of San Carlo, the set designer has used several geometric representation methods (

Figure 4). The first theater image (Table IV) is the plant in which all the specifications are listed in the legend. The second (Table VI) is a perspective section in which all theater venues set up for the

Great Dance are meticulously described. In the third (Table IX) there are two section-prospects: on the left, the entrance to the theater is visible; to the right, the prospect of richly arranged stages and half the real stage. This elaborate represents an explained projection of the curvilinear space of the stalls. The last picture (Table X) depicts the scene of the

Great Dance in Mask according to the geometric method of the central perspective.

On Sunday, November 19th, the solemn feasts took on an urban dimension. The Largo di Palazzo saw the presence of a Cockaigne, as large as the square that, built on four levels, was covered with all kinds of food and equipped with water and wine fountains (

Figure 5A). The Cockaigne, as a ritual, was plundered by the people after the festivities. Finally, at Largo di Castello, an

Artificial Fire Machine was set up at the end of all celebrations (

Figure 5B,C).

The pyrotechnic machine had in plant an octagonal matrix. Along the main crossing axis there were two access ramps leading to the center of the structure. Nearly four of the eight sides of the octagon were joined four squares protruding from the octagon of reference, which served to accommodate the bases on which statues were placed (

Figure 5D).

The pyrotechnic machine internal structure consisted of four bearing elements, arranged along the 45° axes, which inside were placed winding staircase to reach the upper level overlooking the square bases. Between the four bearing elements, four arches were opened, which, being along a cylindrical surface, were curves of the fourth order. A high circular tambour and curvilinear section joined the carriers to the top. Overall, the pyrotechnic machine was very impressive with its largest plant of 200 Neapolitan Palm (about 53 m) and in height 240 (about 63 m).

3. Visualization of the Macchina del Fuoco d’Artifizio in Largo di Castello

The digital model visualization corresponding to the

Artificial Fire Machine has been made through a conversion to the dimensions of the ‘neapolitan palms’ shown in the drawings contained in the

Narrazione. Using digital drawing, through a reverse-conceptual operation and

modeling and

rendering techniques [

9] was generated virtual images (raster) of the pyrotechnic machine [

10].

Specifically, the

modeling construction of the geometric model [

11] of the pyrotechnic machine has served as a basis for

rendering architectural views carefully chosen to simulate perceptional adherence to reality. In this sense, the restitution phase here was the ‘putting in shape’ of images of the pyrotechnic model attached to the

Narrazione, each of which is constructed in function of the position of the point of view and according to the specifics to communicated [

12].

The possibility to represent the three-dimensional model of a pyrotechnic machine founds reason in the presence of the technical drawings in the Narrazione (plan and section-front), which allow to draw metric and geometric data of the architectural organism in question.

The creation of new images has been structured in such a way as to give distinctly scenes created with a man-height observation direction and top-level urban images [

13].

The reference to the different geometric construction [

14] for imaging was intentionally oriented to better represent the event. In addition, integration between images created ex-novo (three-dimensional model of the pyrotechnic machine) and existing images of the city of Naples were used, such as iconographic sources representing the Largo del Castello.

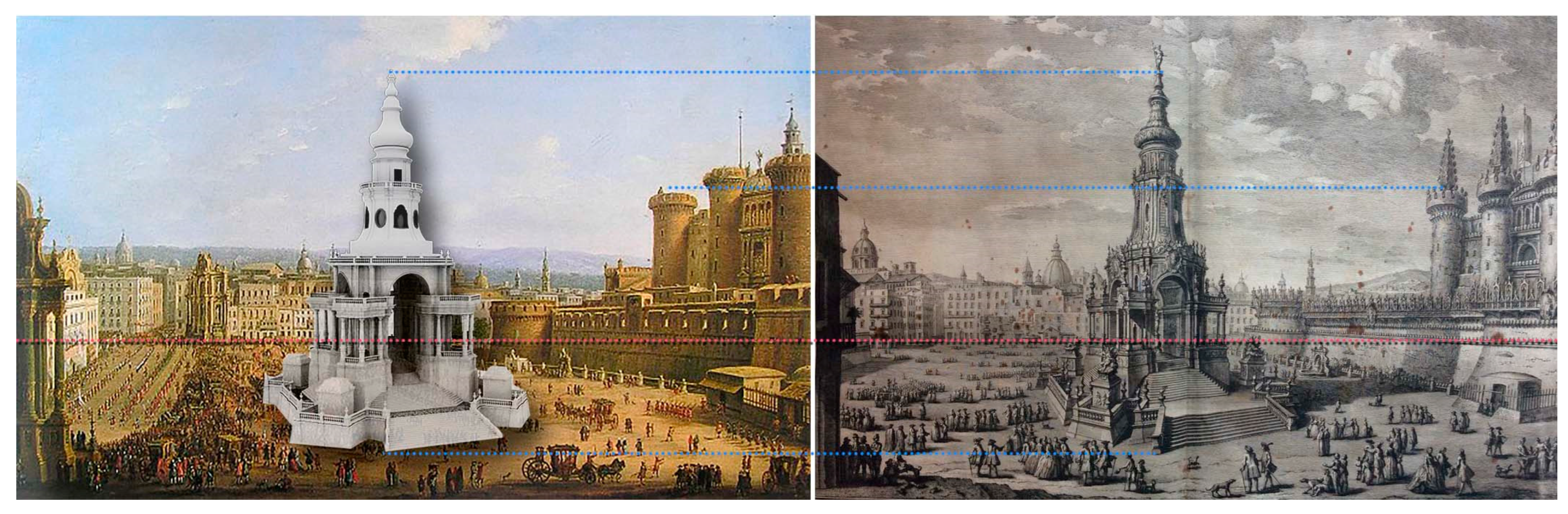

The first prospective image (

Figure 6) shows a possible view of the pyrotechnic machine built at the man height and, therefore, given its remarkable height (about 63 m) and the reduced visual viewing angle, the architectural organism is not taken in its entirety. Thanks to the historical iconographic documentation of Largo del Castello, it was then possible to contextualize the machine in the urban area, placing the Vesuvio profile and the front of Castel Nuovo in an appropriate scale ratio [

15]. The next graphic operation was to place of the pyrotechnic machine plant in the

Mappa topografica della città di Napoli e de suoi contorni by Giovanni Carafa Duca di Noja (images 11 and 18), according to a similar scale, edited in 1775, but, as it is known, it was written around 1750 and therefore near to the time of solemn celebrations (1747) (

Figure 7). The machine placement took place by observing and analyzing the

Perspective of the Artificial Fire Machine,

located in the Piazza del Castel Nuovo (Table XIII), contained in the

Narrazione, with the pictorial work by Antonio Joli of 1757 representing the square on a carnival from the same point of view (

Figure 8). Based on these documents, it is assumed that the pyrotechnic machine could have been located at a point of the Largo, next to the current Santa Brigida Street, to allow (through the coaxiality of the arches of the pyrotechnic machine on the aforesaid road) to catch from Via Toledo the scenic machine and part of the Castel Nuovo front [

16].

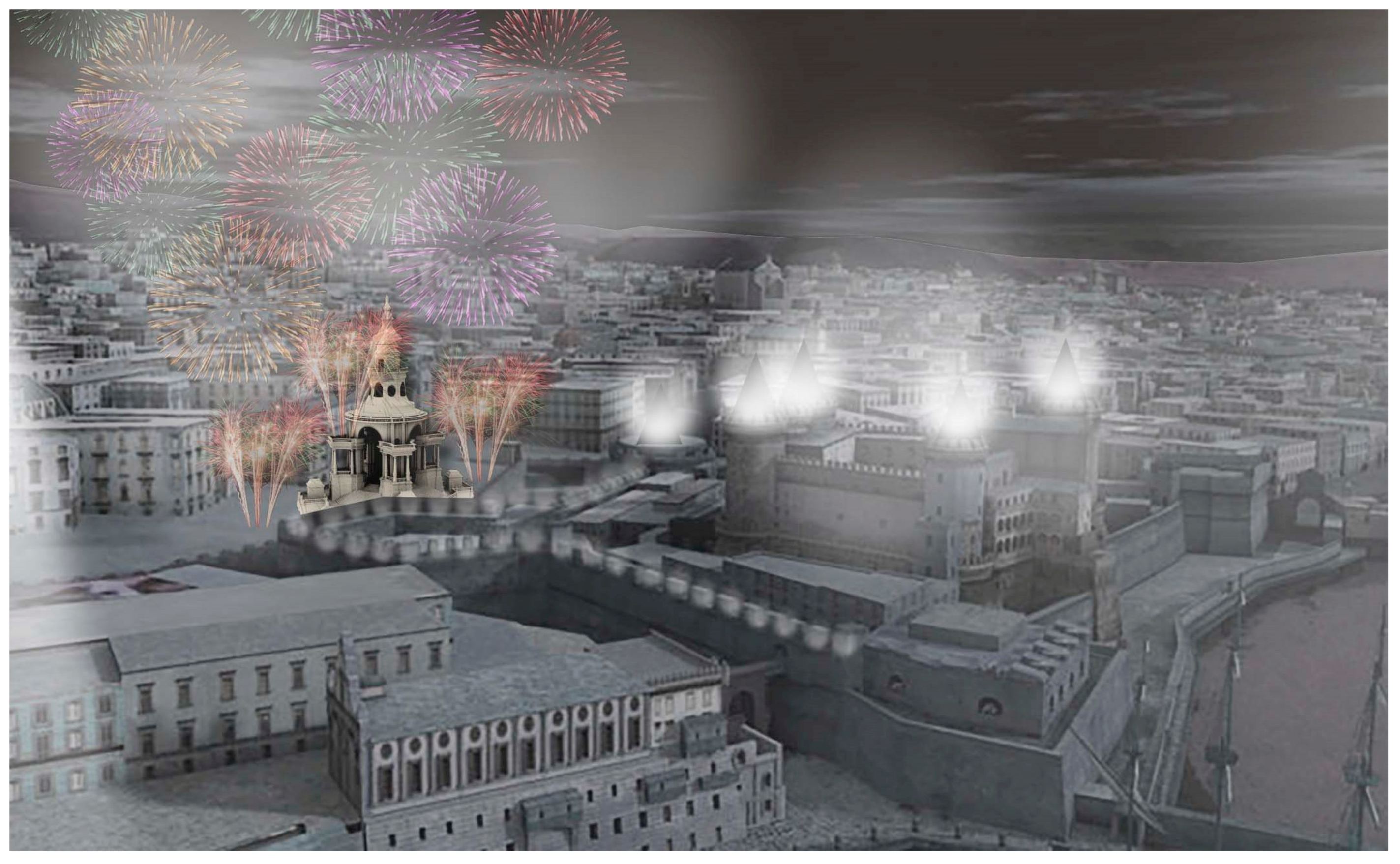

The urban scale image was built by placing the digital model of the pyrotechnic machine in an eighteenth-century reconstruction of the Naples city by the

Pixel ‘06 Association [

17], which shows the area of the Castel Nuovo fortified citadel with a high viewpoint [

18]. The insertion of the pyrotechnic machine was carried out using a single color (given the insufficiency of sources for a possible machine color hypothesis) and using allusive graphic fire effects, luminaries (located along the castle battlements) and the light pyramids (located on the towers of the same to provide the square of an immense light) (

Figure 9).