1. Introduction

Since the time in which modern image recording and reproduction techniques began to make headway in western society, most significantly between the late 19th and early 20th centuries with photography and cinema, social sciences have used these instruments as formidable potential supports for research. Within their mother disciplines, firstly visual anthropology and later visual sociology defined their own scientific contribution on two levels: the first as a support to empirical research through the production of iconographic material; data collection and analysis was no longer based merely on note taking and written documents, tests and questionnaires, taxonomies and descriptions, but could also use visual data in the form of photographic materials, films and videos.

In the field of cultural anthropology, the assertion of the visual dimension constitutes a powerful and necessary device for establishing the way of conducting research that is typical of this discipline [

1,

2]. In the sociological field, it was above all in the second half of the 20th century that the call for visual sociology was made, exploiting the potential of photography and cinema to observe and record social phenomena linked to everyday life, the data of which escapes perception due to its dynamic flow or because, paradoxically, it is “invisible” to the eyes of all [

3,

4,

5]. Also thanks to this way of observing and analysing reality, the qualitative dimension of sociological research, traditionally deemed the weaker (and more inconsistent) area in scientific terms compared to quantitative research, began to take shape. Just as, traditionally, anthropology preferred to give more scientific credit to written works rather than images, which were somehow deemed aphasic. Margaret Mead’s thoughts on this still represent a sort of ethical and epistemological “manifesto” in the field of ethno-anthropological sciences today. In 1973 Margaret Mead strongly criticised the obsolete scientific framework of academic anthropology. While cultures were disappearing all over the world, she wrote: “departments of anthropology continue to send fieldworkers out with no equipment beyond a pencil and a notebook, and perhaps a few tests or questionnaires—also called “instruments”—as a sop to scientism” [

6]. Mead defined “criminal neglect” the neglecting of visual documentation in anthropological research.

Over time, Visual Anthropology and Visual Sociology have defined their own fields of study and research that place visual productions as specific objects of investigation. In other words, it is not a question of merely producing visual materials for anthropological or sociological research, but rather to carry out research on visual and audio-visual production which, in its various forms, is considered a social and cultural phenomenon. An important role is played by “social photography”, i.e., the use of photography to document the conditions of social life and everyday reality. Born in Great Britain in the late 19th century, it was developed above all in the United States from the 1930s onwards. Equally important is the role of social documentary cinema, the “maestro” of which was Norman Grierson: he himself defined the term “documentary film”, and masterminded the birth and development of the group which in Great Britain in the Thirties laid the productive and cultural foundations of this form of cinematography. The work continued in the Forties in Canada with the foundation of the National Film Board/Office National du Film. This set of factors has progressively strengthened and animated the epistemological debate within anthropological and sociological research, and we have also seen the educational repercussions of disciplines which have a particularly attractive and effective feature in their “visual” dimension.

Nothing similar occurred in the field of pedagogy. While scientific literature—simply consult any bibliographic database—includes a very rich international production under the headings of “Visual Sociology” and “Visual Anthropology”, if we use the terms “Visual Pedagogy” or “Visual Education”, we can find no semantically parallel references to those of the other disciplines mentioned. What does appear are mainly contributions of studies and research on the use of iconographic devices in the educational and teaching field, or the educational impact of the visual culture through the media. In fact, the words Pedagogy and Visual, combined together, refer above all to topics linked broadly to Media Education, Media Literacy, and in some cases to Special Education. My attempt here is to verify and if possible recognise a field of study and research which can be defined as “Visual Pedagogy” parallel to the models of visual sociology and anthropology, but which have as a field of reference the manifestation and visibility of the educational experience.

2. Open School

One plausible reason for the inconsistency/non-existence of visual pedagogy is that educational phenomena are systematically hidden from the public eye, even when they take place in public contexts such as schools and educational establishments. What actually happens in the time, space and relations within a school belong solely to the view of the actors present on that stage: the teacher and the pupils. We may simplify this by saying that when a teacher enters the class and closes the door behind him, the teaching events are strictly private: only he and his pupils are witnesses to it. Nothing is visible outside. We must ask ourselves what is the consistency of the educational dimension, and if it has a consistency which can give shape to visual pedagogy. We shall start from this issue, which I believe to be an underlying reason, and which I will try to explain with a few examples.

The concept of “education”, just as that of “culture”, cannot be defined according to objective categories; in other words, I cannot show and describe education as I could do by showing a flower, a rock, and ancient manuscript. A rigorous analysis of the concept of “educational experience”, its epistemological consistency and its inherent problems, were offered by the studies on phenomenological pedagogy begun by Piero Bertolini [

7,

8] and the “Education Clinic” group founded by Riccardo Massa [

9].

When we talk of “education” we don’t all know what we refer to: the word evokes a common and generally agreed semantic framework of educational experience, in all its various forms, which is part of the experience of every one of us. We are familiar with its fundamental ingredients: interpersonal relationships, cultural communication, settings, teaching system, subject-related devices. It does however remain abstract if we are not able to make it “visible” through deictic, ostensive processes, i.e., if we do not show or evoke an educational deed as it takes place [

10]. To avoid being a “discourse” on education, the “scientism” of the eidetic dimension of pedagogy (and the language that connotes it) lies in the empirical and practical dimensions of educational experience which, as such, must be able to show off its concrete activity, telling about its cases.

In fact, visual pedagogy would have plenty of material to show, as education is extraordinarily evocative and icastic. The school setting is itself “theatrical”, the interaction between teacher and pupils takes place around an educational dramaturgy, the “staging” of which may have many different communicative methods which, depending on the case, may be filled with emotional and cognitive tension… or indeed boredom. The enactment of this representation, as explained, takes place exclusively “behind closed doors”, it is not shown to anyone else apart from its own actors, who are at the same time the only spectators of the event. As we know and as we will see below, this sometimes brings with it worrying aspects.

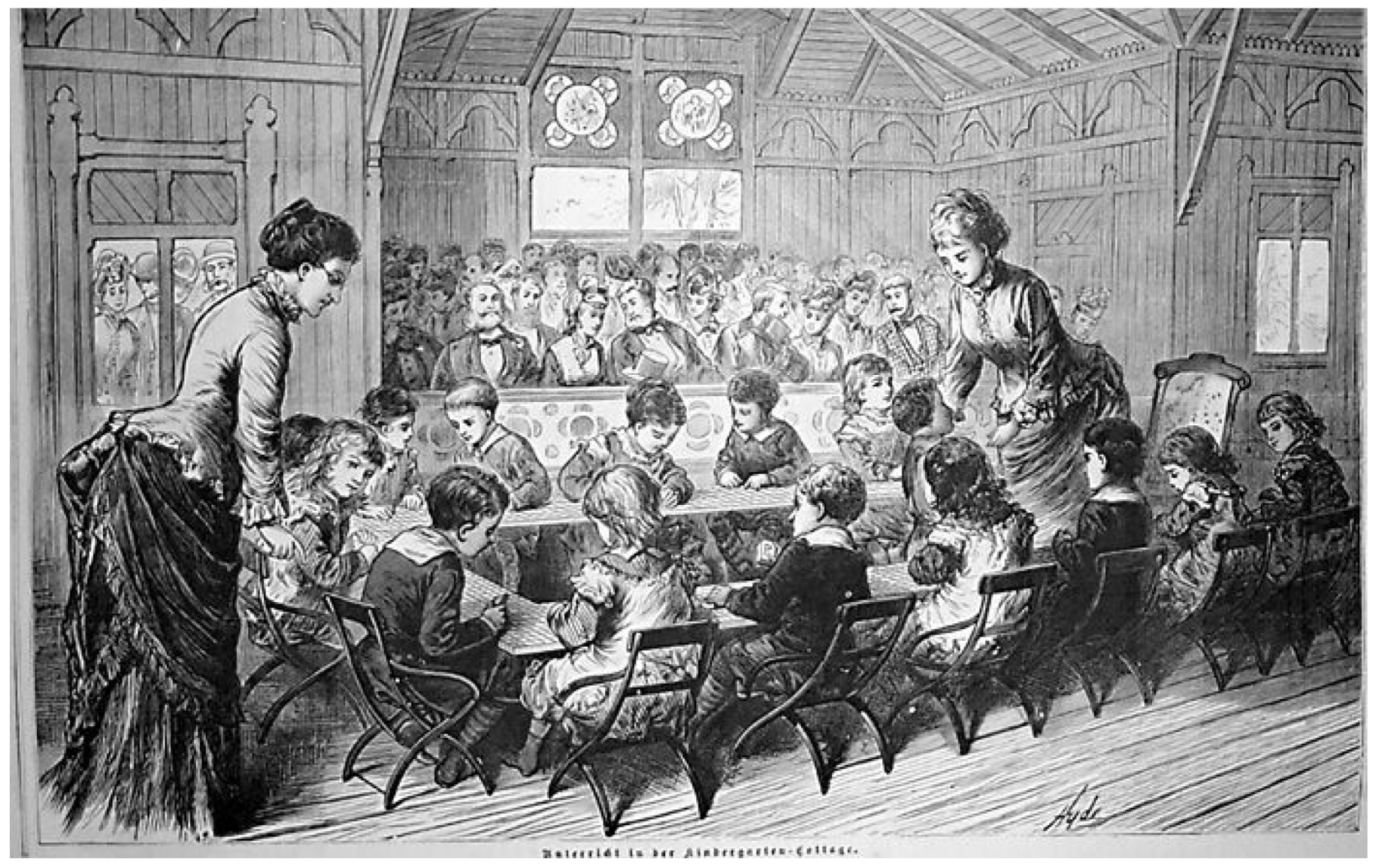

A significant example of pedagogy displayed to all as it unfolds can be found in an image taken at the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia. In the magazine that reported on the event, we can read that in an area of Fairmount Park, a committee of men had a school built according to the Froebelian system. On Monday, Wednesday and Friday mornings, every week, it was possible to see between 18 and 20 children aged from 3 to 6 involved in educational activities [

11] (p.183). The image shows the children with two teachers, sitting around a table shaped in a horse-shoe, with the square-patterned top, busy in the typical activities of the “Fröbel method”, which the journalist describes the essential features of and exalts its educational potential. To one side of the setting, behind a railing we can see a thick crowed of interested people looking on, and we can see more people outside, looking in through the windows, perhaps waiting for their turn to come inside (

Figure 1).

The first way of making pedagogy visible is by showing it off in its normal and concrete execution. This happened in recent history, and still happens when educational and school experiences are implemented using innovative and experimental methods, or which are marked by a special willingness to show their way of being and doing education to the outside world. An audience, comprising above all other education professionals, interested in seeing an educational action for themselves, with the necessary discretion, in order to understand its meaning, gather information directly from the persons involved and observe the setting in which it takes place. The concept of “Open School” has been used in pedagogic language for some time, and indicates a school that is open, within the community, to the many educational demands that go beyond the strict meaning of teaching; this concept does not always express the willingness of the school to show itself in its everyday being.

The consistency and identity of visual pedagogy demands that the repertory of images available are in any case ascribable to this field and able to offer significant material for empirical, didactic and historical pedagogic research. We must therefore restrict the field of reference to what we call visual pedagogy, referring to images which refer specifically to scholastic or extra-scholastic educational contexts. In other words, the image must either speak of a specific educational setting because it directly shows it to us, or must be accompanied by captions guiding us to read the image through the pedagogic intentionality of the person taking it.

Three considerations: the first is that visual pedagogy has a much more specific field of reference than visual anthropology and sociology, where concepts of “culture” and “society” are so broad that, in theory, they contain all visual material which can offer socio-anthropological insight. The second is that visual anthropology and subsequently sociology were progressively defined starting from modern image recording and reproduction means, i.e., photography and cinema, two technologies born and developed in the bosom of the culture of positivism, that very culture which contributed to giving scientific identity in its modern sense to social sciences. Pedagogy, with a much more ancient history (and therefore a different and at times ambiguous epistemological basis), can use much broader visual repertories and, if we take the advent of photography as the watershed, we can talk of ante-photography and post-photography visual pedagogy.

Finally, a third consideration, common both to visual anthropology and sociology, and visual pedagogy: the iconographic repertories used for study and research are made to be “visual” and are therefore not “true”. The interpretation of “visual data”, the role of captions are topics which have been widely debated in the referred socio-anthropological literature, and the same must be said for visual pedagogy. We may use categories of semiotic analysis: verisimilitude and truth do not exactly overlap, but remain within an ambiguous, open relationship. From the point of view of Visual Pedagogy, an image or repertory of images are significant only in relation to their being analysed using pedagogic structures and assumptions. In this sense, what is “unspoken” of an image is rich precisely because an image “speaks” (Also concerning the processes of reading and interpreting visual texts, we may refer to the concept of “Lector in fabula”, and that of “Intertextuality”, [

12,

13,

14].).

3. Observing and Documenting: The Contribution of Reggio Children

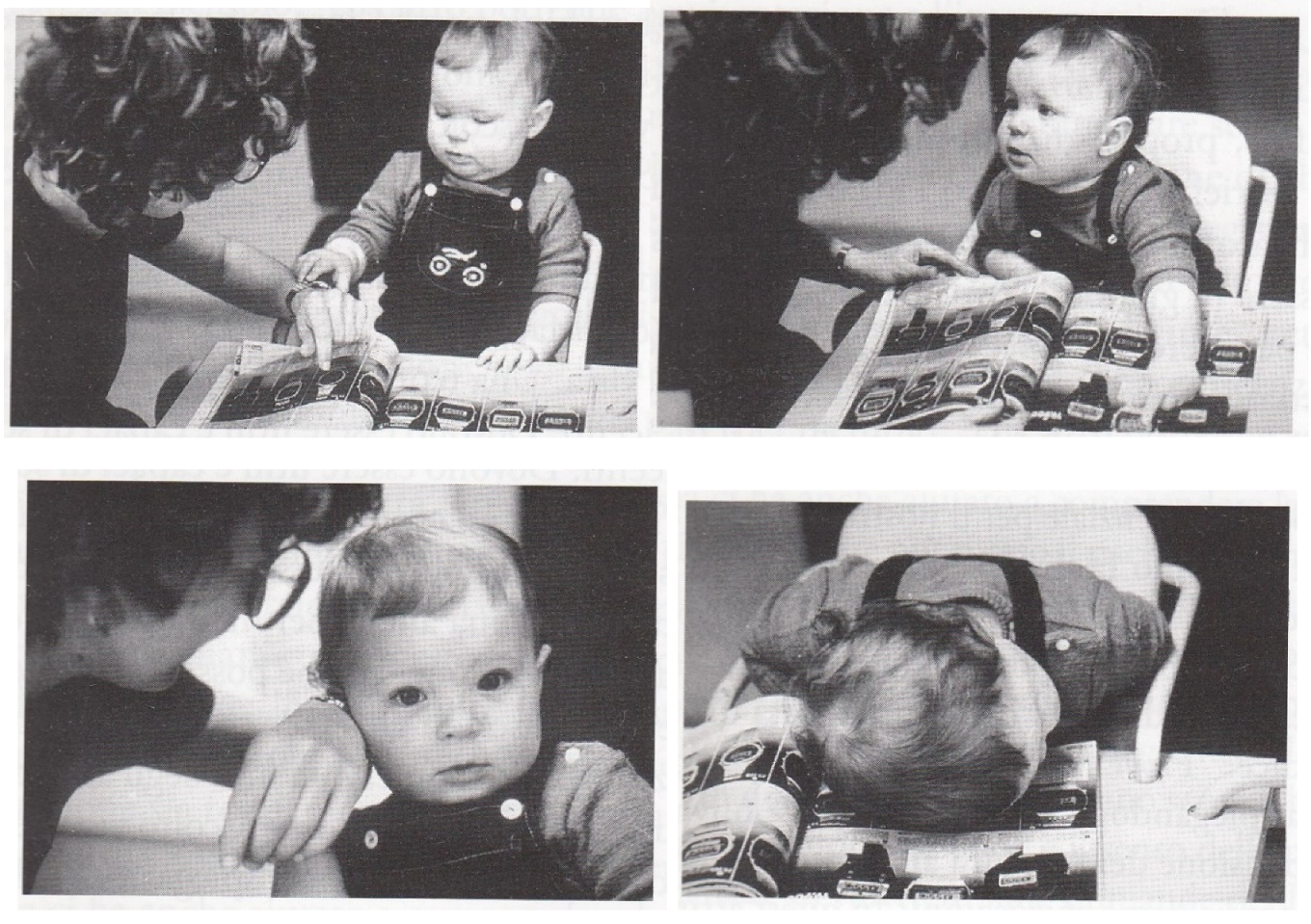

But let us leave the suggestions of a visual pedagogy made essentially of illustrations and paintings, before photography, to enter the specific dimension of the post-photography period, thus in line with the fields of visual anthropology and sociology. Here too we could analyse photographic and documentary repertories offering representations of educational settings and situations for the purpose of critical analysis, as we did, for instance, in the previous examples, but this is not the epistemological nucleus which, alone, can justify the demands and originality of visual pedagogy. It is with the assertion of the method of observation applied to empirical and experimental pedagogy, using modern instruments to record fixed and moving images that we can say that we have developed whole collections of materials ascribable to “visual pedagogy”. In 1981, I took part in an interdisciplinary research group, coordinated by Matilde Callari Galli, on play in some 0-6 preschools. The qualitative part of the research aimed to analyse the methods by which groups of children interacted with unusual play materials compared to what they usually had to play with in the class. Both during the research and after it was published, I was in charge of the video and photographic observation which was to provide the empirical material used to construct the analysis and verify the hypotheses. At that time I reflected on the role of photography in the observation and representation of childhood [

15]. The method of observation in the education field is one of the key features of modern pedagogy, which we find in Rousseau’s

Émile and which was fully and scientifically developed by Montessori. The first text fully describing educational experiments using the method of observation is

Il ragazzo selvaggio, by Jean Itard, published in two parts between 1801 and 1807 [

16], not by chance widely cited by Montessori. The fact that both Itard and Montessori were physicians leads us to consider the application of the observational method in the pedagogical field as a tool linked to clinical and diagnostic aspects which, with all the due differences, concern both medical and psycho-pedagogic practice. Concerning Itard’s work, we must also refer to Francois Truffaut’s film

The Wild Child (

L’enfant sauvage, France, 1968): an exemplary work demonstrating the extraordinary potential of fiction films in the field of visual pedagogy.

The application of visual and audio-visual technologies for the observation of children’s behaviour in educational institutions marks a leap in quality in terms of research and its repercussions on the processes of communication and innovation in the pedagogical culture, comparable to what photography and ethnographic cinema have represented for visual anthropology. To be able to talk of visual pedagogy we cannot limit ourselves to the act of observation, but we must also make the step from observation to documentation. The two terms are not synonyms, and their etymology unveils their respective meanings: observe (servare) means to take into consideration, observe to conserve, it is therefore an essentially subjective act placing the person in relation to what is observed, whether a landscape or a playing child. Observation includes, perhaps requires, listening which is an attitude which apparently contradicts the traditional role of educational communication, where it is the child, the pupil, who listens to the teacher, not the reverse. This is a change in perspective that profoundly affects the very structure of the educational relationship, by its asymmetrical nature.

Documenting refers to

doceo docēre and therefore to an object of communication:

the document is a testimonial of something, it possesses a language that makes it readable and interpretable. The work involved in the passage from observation to documentation offers the most scientifically significant contribution to visual pedagogy. Carlina Rinaldi defines documentation as “visible listening”, as “It ensures listening and being listened to by others. This means producing traces—such as notes, slides and video—to make visible the ways the individuals and the group are learning” [

17] (p. 237–238). The reference to the pedagogy of Loris Malaguzzi and the ensuing work of Reggio Children are an essential, internationally recognised point of reference in the construction of a practice and theory of documentation as an essential part of the pedagogic profession and the quality of the educational experience.

The change in step was made by considering documentation not the collection and assembly of visual materials at the end of a path, to be framed as a kind of “souvenir” of an experience carried out in a given timeframe, but rather a methodical and intentional work accompanying the experience itself and contributing to its scientism. Photographs and audio-visual traces which are the result of the systematic work of observation of a specific educational action or situation, as observation is necessarily selective, become part of a path of reading and interpretation, they are “interrogated” by the persons following that experience. Selected and accompanied by captions, they produce a documentation which is the

accountability of the experience: “By making the pedagogical work both visible and subject to a democratic and open debate, documentation […] assumes that we must take responsibility for our actions and practice” [

18] (p. 226–227).

The volume

Rendere visibile l’apprendimento, produced by Project Zero at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and by Reggio Children [

19] is the most scientifically complete work of visual pedagogy we have available in the field of the documentation of children’s learning processes. The title itself (“making learning visible”) explains this project aiming to bring teaching to a level of representation and narration able to trigger an interpretative dynamism of change. The photographic sequences on the children’s activities, the accompanying captions and the methodological analyses demonstrate a research-action work showing how images are a complex and rich pedagogical research tool. It is not the quantity of images which ensures the quality of the documentation, but rather the selective significance of constructing the steps of the actions carried out by the child as he learns: it is the sense of the Latin proverb attributed to Quintilian “Non multa, sed multum” (“not many things but much”) (

Figure 2).

The use of photography as a tool and language of analysis of the educational experience by the teacher, in a preschool educational context, taking as a point of reference the work of Reggio Children, is the topic of research carried out by Moran and Degano [

20]. They state that “Photography is a dynamic representational system that uses signs to produce and communicate meaning—just as we do when we use words to speak. […] Just as speakers search for the right word, teachers who use photography as a language of inquiry search for the right angle or how closely the camera comes to the children or scene being photographed in order to convey a particular message”.

Though without mentioning visual pedagogy, Moran and Degano make explicit reference to visual anthropology and sociology which had the merit of legitimising photography as a research method: “Through the creation of thick descriptions or the layering of interpretations, photography has emerged as an integral part of the study of signs and symbols that constitute research data and advances our understanding of events, behaviours, and scenes in context. For example, when does a specific gesture mean something, or in what ways do particular classroom routines that emerge within a group of children have meaning in that space? The creation of a thick description then is an attempt by the anthropologist, sociologist, or teacher to move beyond surface-level descriptions toward interpretations, informed by more than one way of seeing or illuminating a phenomenon. This can be accomplished through the creation of a series of photographs and/or the coupling of photographs with artefacts, transcriptions, and explanatory text to reveal an in-depth, full-bodied, and contextualized interpretation”.

The volume by Manuela Cecotti [

21] on photography in educational contexts is until now the most complete attempt of a theoretical and practical development of this topic. The author places the accent on the non-neutrality of the photographic documentation, as an educational experience cannot have any claims to “neutrality”. In making learning contexts and processes visible, photography also holds an idea of childhood and educational establishments linked to the view of the educators, which is inevitably selective and interpretative. This does not set a limit for visual pedagogy, but rather a value, as it makes visible not only the learning experience, but also the intentionality of those who set up the experience and who do not intend for it to be hidden.

In visual pedagogy, in terms of both research and training, we can find the application of that method which in visual sociology is defined as

Photo-elicitation, obviously with different characteristics from the typical features of social research [

22,

23]. It is a question of bringing to the attention of a group of persons (in our case educators, teachers, parents, …) the images of an educational documentation and stimulating their reading and interpretation, thus gathering data and information both on the communicative strength of those images and the “experiences” emerging in the people reading them. It is interesting to note how, in the pedagogical context, the process of elicitation can also involve the children who, when faced with the images of their actions, with the narrative mediation of the teacher discover that “what they do has value, it “makes sense”. And so “they discover that they “exist”, they can leave the anonymity and invisibility and what they say and do has value, is heard and appreciated: it is value” [

24].

4. The Visual Pedagogy of Alberto Manzi

It is almost a pedagogical oxymoron to state that education, the most culturally significant phenomenon in which our society invests for its future, is also the most hidden, while children are the most photographed subject in the world. Excluding some areas of preschool education, which has been the focus of particular psycho-pedagogical attention in the past forty years, and which not by chance has expressed the highest level of experimentation of educational models, the various levels of school remain substantially closed to the external eye. In fact, visual pedagogy would have plenty of material available, as education has an extraordinary evocative and icastic capacity; the school setting is indeed dramatic and “theatrical”, teaching can be also read as a great “pretence” [

25,

26], but it is not revealed to indiscreet onlookers and its “actors” are at the same time merely the spectators of the event.

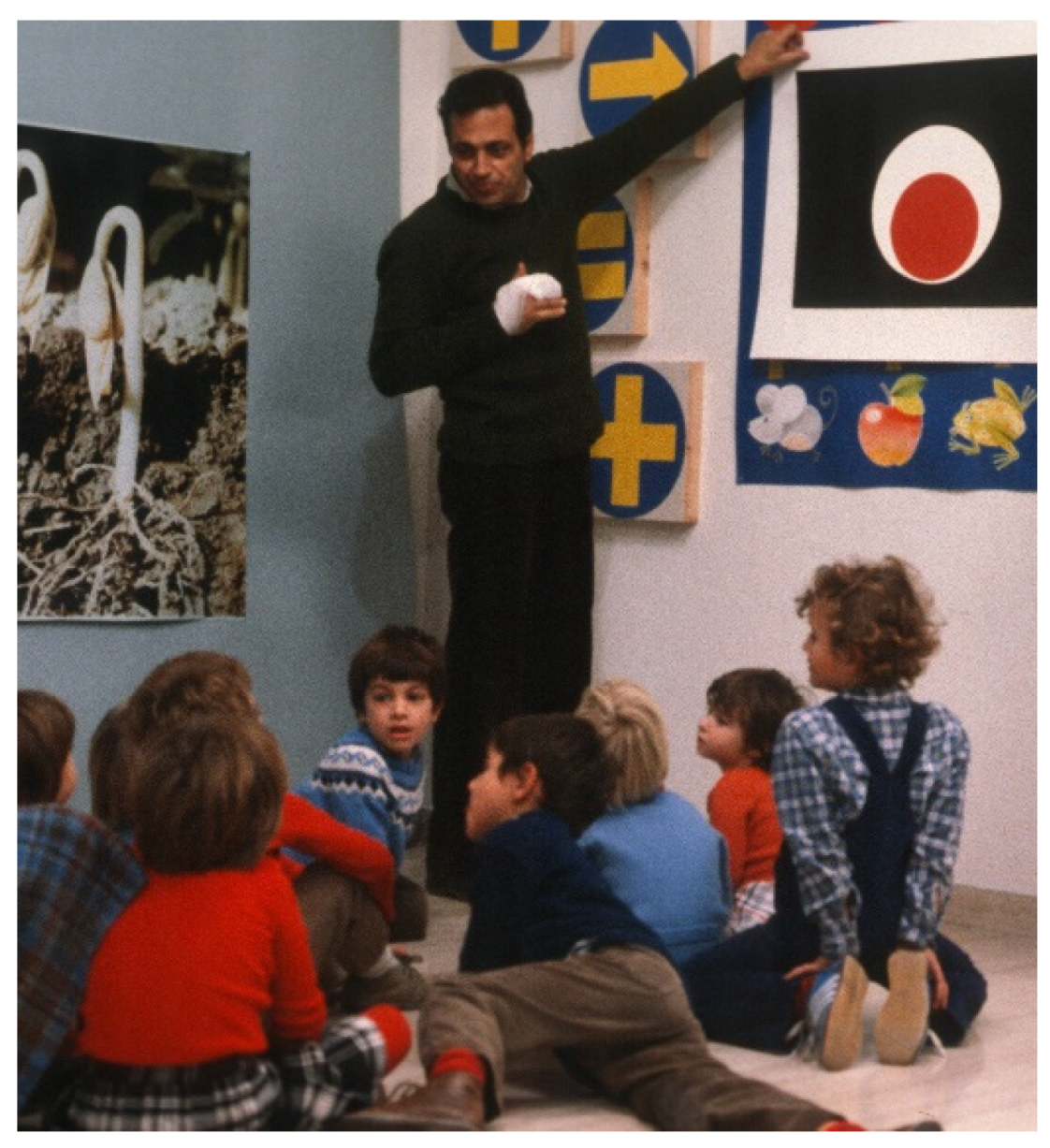

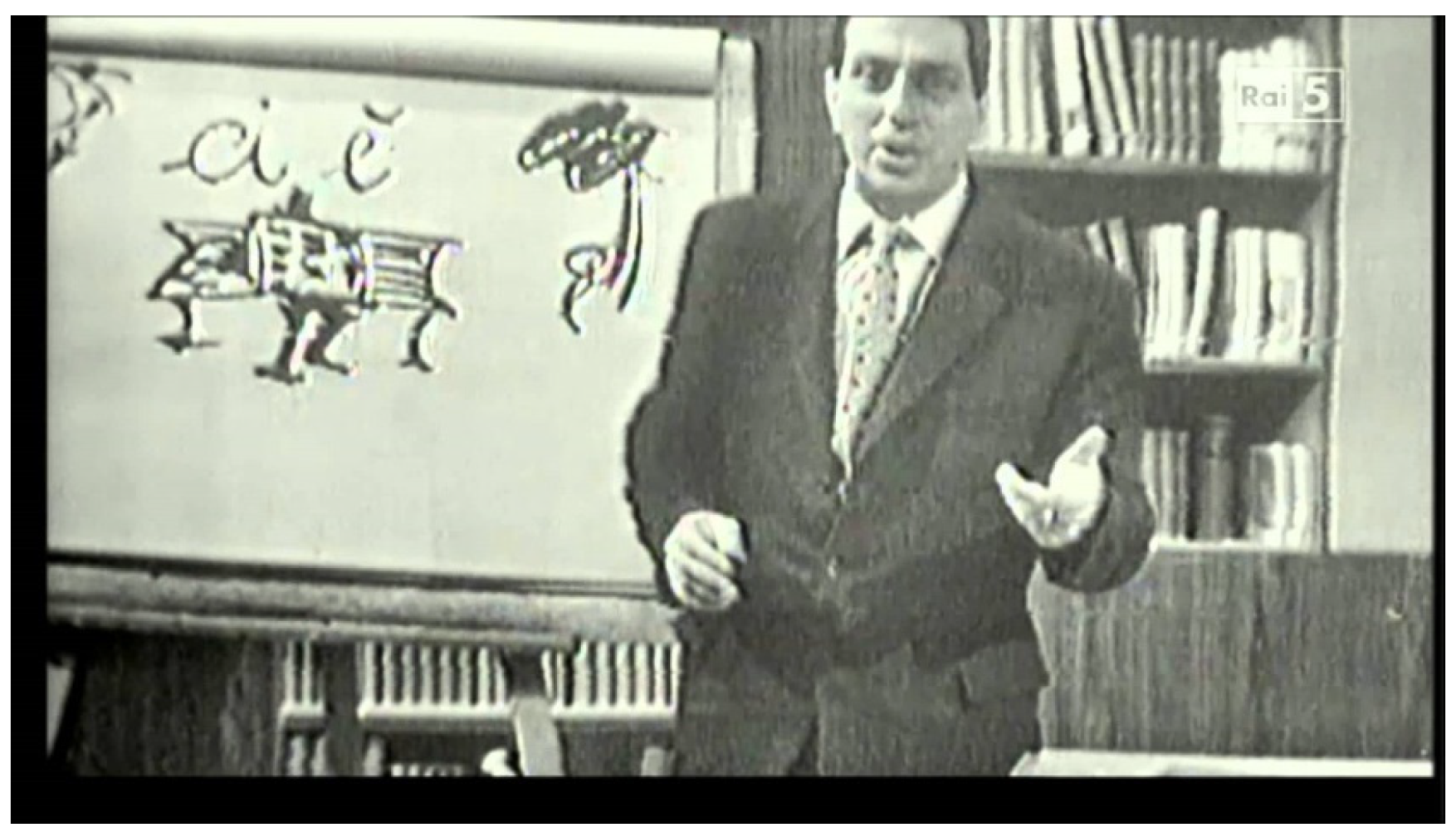

Alberto Manzi (1924–1997) deserves praise for having offered one of the most important contributions to visual pedagogy in terms of both quality and quantity, above all in primary schools. While for nine years from 1960 to 1968

Non è mai troppo tardi (

It is never too late) he gave both form and image to educational communication on TV for illiterate adults. The huge success of the programme went way beyond its target audience: “Popular education course for illiterate adults”, the caption stated. On several occasions, Manzi recalled the testimonials of adults who said that they had started to learn to read and write when they were children, before they went to school, by watching his programme on TV. Subsequently, with the series produced in the Seventies and Eighties (

Impariamo a imparare;

Fare e disfare;

Educare a pensare) he brought his way of working in schools with children to the TV [

27,

28]. Primary school teacher for thirty years, Manzi was also an important novelist and author of children’s stories and other books on cultural diffusion, author and conductor of radio and television programmes on educational topics. In 2014 Rai Uno dedicated a two-part television fiction to him:

Non è mai troppo tardi directed by Giacomo Campiotti. The Department of Educational Science of the University of Bologna and the Emilia-Romagna Region established the “Alberto Manzi Centre” which houses the archives of his works, promotes research, cultural and educational initiatives based on his works (

www.centromanzi.it). (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Alberto Manzi’s visual pedagogy is based on clear explanations and exemplary methodological rigour, without neglecting the prerogative of the means: keeping the audience’s attention. He found a fair balance between the need for synthesis imposed by the television and the timing of the teaching action which, at school, is necessarily slower. The setting is that of a group of primary school children and the teacher, Manzi in person, initially seated or standing in a semi-circle. The teacher begins by asking a question, for example: what is the difference between absorb and assimilate, why does a given object float, what is inside our body, what is force … and the children freely offer their answer to the question which constitutes the topic of the episode. In the sequence of dialoguing statements that follow, confirming and contradicting each other, where the children’s answers (but also their doubts and silences) express a communicative, intellectual liveliness, fantasy and reality are mixed together in a string of thoughts and words which are often surprising, and not without the occasional gag.

This phase is followed by an active, empirical phase where the children try out their hypotheses and exchange ideas. The materials are mostly common objects, those used by the children to create their experiences and, mostly unconsciously, form their own concepts. The children try out what they had previously thought and said, and as they do so they are stimulated by Manzi to speak, say what is happening, in a situation in which curiosity blended with the pleasure of doing and discovering animates their interactions, arousing in the spectator the same interest that can be seen in the group of children.

Contrary to notionist, abstract teaching methods, Manzi shows the educational feasibility of an epistemological change in school teaching, regarding the way of thinking and establishing the children’s relationship with the learning experience. Not by chance, Manzi focuses above all on scientific education, as in this field more than others traditional teaching based on the spoken transmission of concepts and notions by the teacher or the text book shows all its educational inconsistency.

Alberto Manzi’s visual pedagogy is developed around a dual register: the first is that of the action of the teacher with the children, where the images show what they say and do on the basis of the topic being dealt with. The second is that of a kind of “estrangement”: the teacher leaves the educational action for a moment and talks directly to the television audience, inviting them to understand a certain passage, read what they are looking at from a specific point of view. Thus teaching reveals all its artifices and intentionality.

Manzi’s communicative skill and educational creativity give us the idea of a way of “doing school” that the television representation allows us to understand in all its suggestions and cognitive provocations. Although he widely and magnificently used writing as a means of expression and communication, Manzi never wanted to write any work describing his teaching methods in an organic, systematic manner; he was aware of having left a work of visual pedagogy in which it was possible to directly understand his thought-in-action; this is a unique case in Italian pedagogical culture (

Figure 3).

5. Docu-Fiction

The possibility to analyse the educational phenomenon through specific visual repertories is rare. Photographic and film documentations on school and extra-scholastic educational experiences over a century, from the early 1900s to today, which offer significant materials, should be the subject of research, in the sense that it should be sought out. Affirming the role of visual pedagogy in all its past and present forms in which the representation of the “educational deed” can be visually documented and reconstructed, is now an essential demand in the field of educational research.

The most modern film and video recording equipment is lightweight, complex equipment is not required, and it is now possible to create docu-fiction works based on the most interesting materials in order to create the body and identity of visual pedagogy. It is a form of cinema which seeks to represent a given reality by using—with low impact—some devices of fiction (scripts, reconstruction, staging, actors, post-production) to ensure a better documentary basis of the film, and its being a “cinema of truth”. A significant part of the visual anthropology repertory was formed on this genre of cinema productions, particularly the works of Robert Flahery (1884–1951) and Jean Rouch (1917–2004). In practice this involves creating the conditions that allow reality to be manifested for what it actual is, via the film. Cinema takes on a non-directive, discreet, uninvasive attitude: in a word: unobtrusivly.

The most important work of this kind made in Italy was

Diario di un maestro, in 1973, produced by RAI and directed by Vittorio De Seta. Freely adapted from the book

Un anno a Pietralata written by teacher Albino Bernardini, published in 1968, the film shows the work of a fifth year primary school teacher in the outer suburbs of Roma, his pedagogical and institutional struggle to cope with school abandonment as the result of the failings of the school itself. From the words of De Seta we can understand the meaning of visual pedagogy in this work: “The fundamental choice was that we did not make a film: in fact we made a school and we filmed it. My position was one of absolute modesty. […] Making a film about a school that must not be notionist, which must not be “taught”, automatically becomes a film that cannot be “interpreted”. As you abolish textbooks, you must equally abolish the script” [

29] (

Figure 5).

A number of works belong to the visual pedagogy of docu-films, here I limit the references to two recent and particularly significant ones which, in my opinion, are comparable for a number of traits: the French Essere e avere, from 2002, directed by Nicolas Philibert, and the Italian Sotto il Celio azzurro, by Edoardo Winspeare, from 2009. In both cases the films show a school year in a school with very special connotations: in the first film the school is in a small town of around 300 inhabitants in the French region of the Massif Centrale. The school is attended by 13 children aged between 4 and 13 in a single class, overseen by the patient professionalism of a teacher whose house is in the school building. The second film tells of a preschool in Celio, Rome, attended by 45 children from over 30 different nationalities and in which the work of the educators is that of “taking care” not only of the children’s education but also the school, like a common house. The structure of the two films is based on the classic dramatic framework, although adapted to the represented situation; it respects the three units of time, place and action: the time is the ordinary time of a school year, marked by the passing seasons, the place is the school and what is nearby but which is in any case part of the children’s educational setting, the action is that of the life of the school, made of teaching activities and relations.

The “rhetoric” of the docu-film is not that of an action film or a fictional story, but lies rather in its ability to “unveil” reality, “make it speak”, through the filmic artifice. To paraphrase Dziga Verov, the great Russian documentarist and his theory of the “life caught unawares”, where the cinema becomes a sort of “lie detector” able to show reality without any pretence, indeed exalting it, in the field of visual pedagogy we could talk of “education caught unawares”.

The docu-film is to all extents and purposes cinema, it shows the audience an everyday reality like school, a certain school where it captures the spectacularity of the intrinsic, specific pedagogical drama. It does not provoke the audience using mechanisms to identify with the lead roles or to emotionally agree with the pathos of the actions, but it offers the audience a chance to enter, unseen, an environment it does not know, and to see what is happening there. If the film works, there will be many suggestions and reflections. Here we could open the fiction cinema topic to the field of visual pedagogy. There are plenty and indeed some excellent cinematographic productions representing and telling of educational situated through the typical devices of dramaturgy and film rhetoric, at times inspired also by real facts and persons. The pedagogy that has dealt with this so far has done so with mainly training purposes, i.e., taking the filmic text as an assimilable deictic device, for certain aspects, as a “case history”, functional to developing meanings by the learners (students and education professionals). In this regard it is worth mentioning the contributions of Emanuela Mancino [

30] and Alberto Agosti [

31].

6. The Power of Not Being Seen

As I said at the start, one plausible reason for the inconsistency/non-existence of visual pedagogy is that educational phenomena are systematically hidden from the public eye, even when they take place in public contexts such as schools and educational establishments. When the teacher enters the class and closes the door behind him, he creates a kind of pedagogical “apartheid”.

In the past few years, cases of physical and mental abuse by nursery, infant and primary school teachers and educators have come to light and been widely reported in the media. These cases were visually revealed by video recordings from micro-cameras hidden in the schools, installed by order of the legal authorities following reports and complaints. Pieces of these films are shown on TV and can be seen on the Internet alongside the news articles. “If they could see us doing this they would arrest us”, one of the two educators in a nursery school in Piacenza arrested for abusing children said. The Carabinieri intercepted them and video-recorded them for over a month (“Piacenza. Teachers arrested for abuse, tapping”, La Gazzetta di Parma online, 26 May 2017). In a primary school in the province of Messina, the teacher gave the children in a class the following order: “Let it be clear, what happens in the class must never be told at home, what happens at school must stay at school”. Demolishing the wall of invisibility and silence of three teachers, one banned from teaching and another two suspended, were the audio and video tapping showing their “pedagogy” (Alessandra Ziniti, “Messina, the school of horror in the Nebrodi district: three teachers arrested”, R.it Palermo online, 25 May 2016). In the same way, bullying in schools and reprehensible behaviour by teachers in the exercise of their role have been made visually public by live recordings done more or less surreptitiously by the pupils themselves using their phone cameras and published on-line.

From this worrying repertory emerge the shards of that “poisonous pedagogy” described in detail by Alice Miller [

32]. The victims of these events have been not only children, above all in the 0-6 age group, but also the elderly and disabled in “protected facilities” (a definition which, in the light of certain facts, sounds incredibly equivocal…) and the events have led to a draft law, currently being examined in Parliament, on “Measures to prevent and fight crimes against minors in nursery and infant schools and against persons hosted in health and social-health facilities for the elderly and the disabled”. Once passed, the law provides for the installation of closed circuit cameras in these institutions. The many short films that can be seen streamed on the Internet are the selection of many hours of recordings required to capture the evidence of any offences ascribable according to the criminal code (art.571), to abuse of means of correction and discipline. The films are like long takes: they show educational settings seen from above, recorded with wide-angle lenses where aggressive language and physical actions take place, at times clearly violent scenes where children are punished for a certain behaviour, mentally mortified, forced to obey using hard, constrictive methods. These images are then isolated and enlarged to be analysed in detail (

Figure 6).

The characteristic of these materials is that they are based on the dissociation of the relationship between the observer and the observed reality, between seeing and being seen; those who are observed have no idea that their actions and words are being recorded; they are made the object of observation that they are not an aware part of. And it could be no other way, as here it has nothing to do with motivations linked to pedagogic documentation or research, but rather with investigations and the monitoring of persons who could commit offences. If the person knew they were being recorded, in all probability they would modify their behaviour. Therefore, in this case the end justifies the means.

The videos in question are in no way comparable to those done using the candid-camera method, except for the dissociation of the seeing/being seen relationship. In the field of anthropology and sociology the opportunity of the candid-camera method, i.e., of the value for research purposes of photographic and cinematographic images recorded with the total unawareness of the persons being recorded, has been discussed. Chiozzi [

1] (pp. 95–97) highlights that “scientific observation as a process of objective knowledge of the reality as it really is, and the belief that it is necessary, in order to achieve this, to avoid all distortion produced by the presence of the observer, as well as any risk that he becomes involved in any form of “participation” in the observed event” constitutes a myth or an ideology of scientific research. This method is deemed extraneous to visual anthropology, while it is used in the field of ethology and behavioural psychology. When we talk of visual pedagogy we refer to a work where the observer is a part of the observed setting, the recordings are the result of an intentionality which leads him to direct his gaze, select what he deems significant and subsequently interpret it, or incite the interpretation of the interested parties. He relates to the educational situation and the persons involved according to different degrees of participatory methods. So the question we ask is: can we consider the videos representing teaching situations and actions where children suffer violence and the educational relationship is seriously degraded as a repertory of visual pedagogy?

My answer is yes, because, whatever the reasons for which they were produced, and which are not linked to pedagogy, the fact that they show us the dark side of education which exists, which has always existed, even though all too often we have sought to make it invisible. Prefiguring an “Apollonian” education may be gratifying and consolatory, but it risks reducing pedagogy to a feel-good story. Riccardo Massa was right when he wrote that “Education is a sad, dirty matter, but if we don’t do it others will” [

33]. And so it should be the task of pedagogy, its professionals, to make visible the “sad, dirty matters” of education, asking why they exist, how to deal with them and how to prevent them. Otherwise, as is happening, and as Riccardo Massa said, others will do it, and they will tell pedagogy to keep its nose out of it, as it closed its eyes rather than opening them.