A Map on the World of Professional Identity. Visual Narration for Education and Care Workers †

Abstract

:1. Introduction (Emanuela Guarcello)

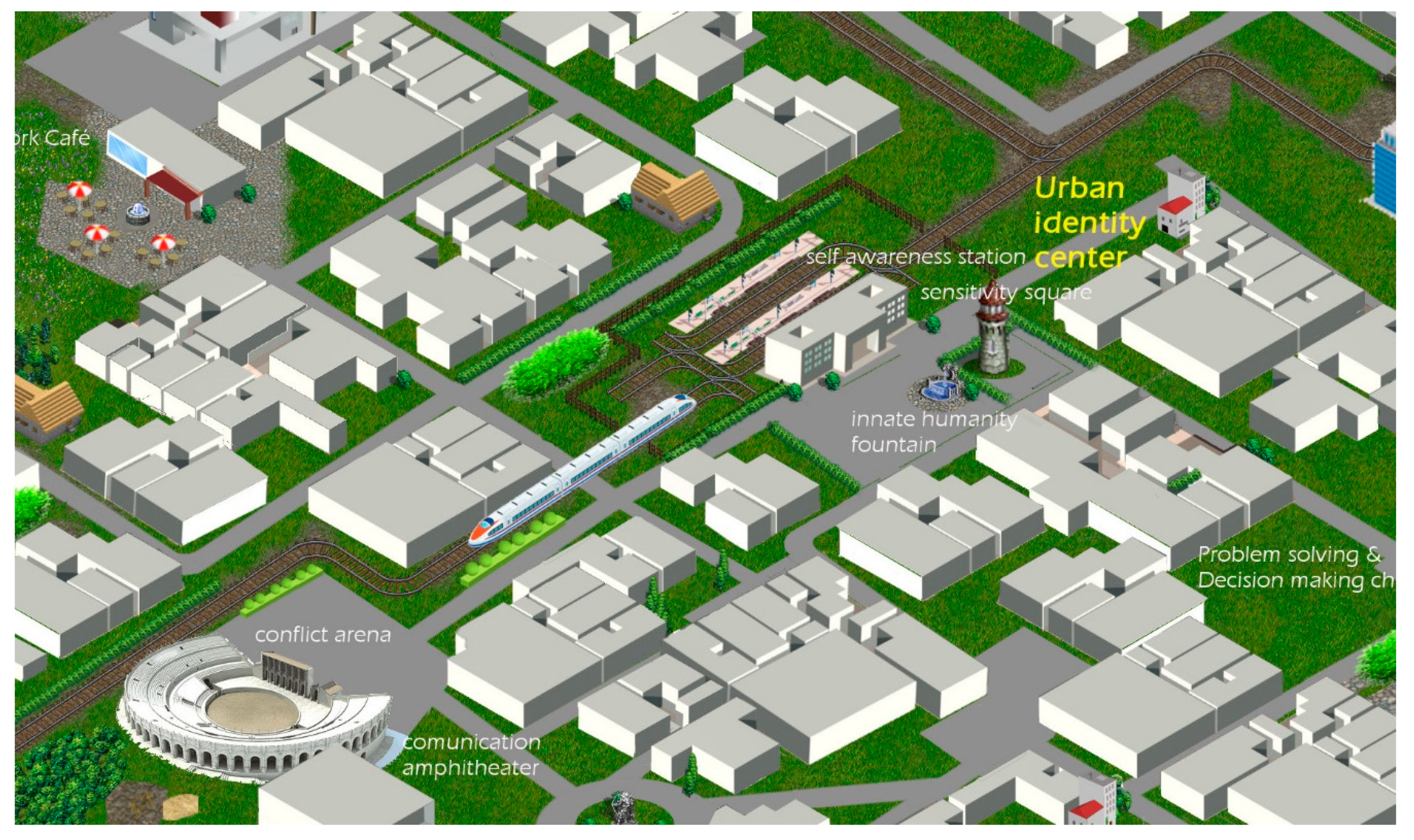

2. Cartography on Professions: Motivation and Objectives of the Study (Paola Zonca)

3. Materials and Methods. The Art of Mapping: ‘Telling’ Outer and Inner Space (Paola Zonca)

- creation of non-linear, personalised paths which represent the vision that the operator has of himself, and of his complex and systematic transformation;

- recent reflections suggest integration of the art of mapping with visual opportunities which, as well as expanding the complexity of the vision, can provide an opportunity to work not only on a “classic” level (map on paper), but also in IT format, thanks to the use of elaboration and post-production technologies on the material mapped using online programs [31];

- the mapping of imaginary places allows the analysis of self-knowledge and own identity: “the impact of maps on personal identity is even more pronounced in emotional cartography, of which the Carte de Tendre is the summary: using narrative forms, cartography has redesigned the very space of the subject” [12] (p. 212).

4. Results and Discussion: Hypotheses of Intervention and Methods of Application (Emanuela Guarcello)

- Tecnical or procedural and instrumental skills: knowledge (theoretical and practical) aimed at the organisation and management of the educational and care intervention;

- Self-awareness: critical thinking and reflexivity, management of emotions, learning how to learn, management of uncertainty and complexity, sensitivity, innate humanity, previous experiences, motivation to professional choice;

- Interpersonal relations with the tram and people: management of the setting, interdependence and team working, networking between services, tolerance of frustration, ambivalence and ambiguity, effective communication, conflict management and management of diversity, transparency, congruence, authenticity (exemplarity), listening and attention, welcoming, understanding people’s needs, empathy, reciprocity and transfert, silence, active liabilities, authority, respect and non-interference, promotion of independence;

- Intentionality: planning, problem solving, decision making, creativity, openness to change in a particular direction (aim), orientation towards the future and pedagogical hope, observation/investigation/research in relation to the present, analysis of past experiences, risk taking and management of unexpected events.

5. Conclusions: Narrability of Cartographic Images (Emanuela Guarcello)

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Formenti, L. Formazione e Trasformazione. Un Modello Complesso, 1st ed.; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italy, 2017; ISBN 9788860309198. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M. Quando L’Adulto Impara. Andragogia e Sviluppo Della Persona, 9th ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2010; ISBN 9788846491794. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. La Teoria Dell’Apprendimento Trasformativo. Imparare a Pensare Come un aDulto, 1st ed.; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italy, 2016; ISBN 9788860308320. [Google Scholar]

- Garrino, L. La Medicina Narrativa Nei Luoghi di Formazione e di Cura, 1st ed.; Ermes: Milano, Italy, 2010; ISBN 8876405009. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz, G.M.; Albury, W.R. The Medico-Artistic Phenomenon and its Implications for Medical Education. Med. Hypotheses 2010, 74, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alastra, V.; Bruschi, B. Immagini Nella Cura e Nella Formazione. Cinema, Fotografia e Digital Story Telling, 1st ed.; Pensa Multimedia: Lecce, Italy, 2017; ISBN 9788867604470. [Google Scholar]

- Strepparava, M.G. L’arte, la musica e la letteratura come strumenti per educare l’attenzione, la sensibilità e la capacità di entrare in empatia con i pazienti. In La Medicina Narrativa Nei Luoghi di Formazione e di Cura, 1st ed.; Garrino, L., Ed.; Ermes: Milano, Italy, 2010; pp. 91–120. ISBN 8876405009. [Google Scholar]

- Nosari, S. La creatività e le sue storie. In Immagini nella cura e nella formazione. Cinema, fotografia e digital story telling, 1st ed.; Alastra, V., Bruschi, B., Eds.; Pensa Multimedia: Lecce, Italy, 2017; pp. 233–241. ISBN 9788867604470. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Democrazia ed Educazione, 1st ed.; La Nuova Italia: Firenze, Italy, 1992; ISBN 8822111540. [Google Scholar]

- Bignante, E. Geografia e Ricerca Visuale. Strumenti e Metodi, 1st ed.; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2011; ISBN 8842096641. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzoeff, N. Introduzione Alla Cultura Visuale, 1st ed.; Meltemi: Roma, Italy, 2002; ISBN 8883534546. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, G. Atlante delle emozioni. In Viaggio Tra Arte, Architettura e Cinema, 1st ed.; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 2015; ISBN 8860101581. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, J. Questione di Sguardi. Sette Inviti al Vedere fra Storia Dell'Arte e Quotidianità, 1st ed.; Il Saggiatore: Milano, Italy, 2015; ISBN 8842821047. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Voglia di Comunità, 2nd ed.; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2003; ISBN 8842063541. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Vita Liquida, 1st ed.; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2006; ISBN 8842076996. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. L’arte Della Vita, 1st ed.; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2009; ISBN 8842088919. [Google Scholar]

- Calvino, I. Collezione di Sabbia, 2nd ed.; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 1994; ISBN 8804382570. [Google Scholar]

- Gennari, M. Pedagogia Degli Ambienti Educativi, 1st ed.; Armando: Roma, Italy, 1998; ISBN 8871447239. [Google Scholar]

- Palomba, E. La Persona e i Suoi Artefatti. Realtà, Virtualità e Immagine di sé, 1st ed.; Armando: Roma, Italy, 2006; ISBN 9788860810892. [Google Scholar]

- Van Swaaij, L.; Klare, J. Atlante Del Mondo Interiore, 1st ed.; Pendragon: Bologna, Italy, 2001; ISBN 8883420659. [Google Scholar]

- Iori, V. Il Sapere dei Sentimenti: Fenomenologia e Senso Dell'Esperienza, 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2009; ISBN 8856805197. [Google Scholar]

- Iori, V. Quaderno Della Vita Emotiva. Strumenti per Il Lavoro di Cura, 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2009; ISBN 9788856811841. [Google Scholar]

- Musi, E. Invisibili Sapienze: Pratiche di Cura al Nido, 1st ed.; Junior: Bergamo, Italy, 2011; ISBN 9788884346886. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, L.; Melacarne, C. Apprendere a Scuola. Metodologie Attive di Sviluppo e Dispositivi Riflessivi, 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2015; ISBN 8891723819. [Google Scholar]

- Brotton, J. Le Grandi Mappe. Oltre 60 Capolavori Raccontano L’Evoluzione Dell'Uomo, La Sua Storia e La Sua Cultura, 1st ed.; Gribaudo: Milano, Italy, 2014; ISBN 8858014308. [Google Scholar]

- Faccioli, P. Altre Parole. Idee per Una Sociologia Visuale, 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2001; ISBN 9788846432087. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.R. The World on Paper. The Conceptual and Cognitive Implications of Writing and Reading, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; ISBN 0521575583. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Comunità di Pratica. Apprendimento, Significato e Identità, 1st ed.; Cortina: Milano, Italy, 2006; ISBN 8860300657. [Google Scholar]

- Schon, D. Il Professionista Riflessivo. Per Una Nuova Epistemologia Della Pratica Professionale, 2nd ed.; Dedalo: Bari, Italy, 1983; ISBN 8822061527. [Google Scholar]

- Schon, D. Formare Il Professionista Riflessivo. Per Una Nuova Prospettiva Della Formazione e Dell’Apprendimento Nelle Professioni, 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2006; ISBN 9788846477033. [Google Scholar]

- Caquard, S.; Cartwright, W. Narrative Cartography: From Mapping Stories to the Narrative of Maps and Mapping. Cartogr. J. 2014, 51, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. Emotional geographies of teaching. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2001, 103, 1056–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.-H. Emotional Geographies of Teacher-Parent Relations: Three Teachers’ Perceptions in Taiwan. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2011, 12, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, D.R.; Betters-Reed, B.L. The personal map. J. Manag. Educ. 2005, 29, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M. Le Nuove Frontiere Della Giustizia, 1st ed.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2007; ISBN 97888452120427. [Google Scholar]

- Nosari, S. Capire L’Educazione. Lessico, Contesti, Scenari, 1st ed.; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 2013; ISBN 9788861842670. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Lo Sviluppo è Libertà. Perchè Non c’è Crescita Senza Democrazia, 1st ed.; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 2000; ISBN 9788852049439. [Google Scholar]

- Capo, M.; Un percorso di promozione all’occupabilità sostenibile: non troppo dietro le quinte … il potenziale interno di occupabilità, le soft skills, il network, e le récit de soi. Metis 2017, VII. Available online: http://www.metisjournal.it/metis/anno-vii-numero-1-062017-lavoro-liquido/203-buone-prassi/998-2017-07-14-15-57-19.html (accessed on 6 November 2017).

- Grimaldi, A. Dall’Autovalutazione Dell’Occupabilità al Progetto Professionale—La Pratica Isfol di Orientamento Specialistico, 1st ed.; Isfol: Roma, Italy, 2016; ISBN 9788854301085. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, L. Competenza Pedagogica e Progettualità Educativa, 1st ed.; La Scuola: Brescia, Italy, 2000; ISBN 9788835098980. [Google Scholar]

- Quaglino, G.P. Gruppo di Lavoro Lavoro di Gruppo, 1st ed.; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italy, 1992; ISBN 9788870782325. [Google Scholar]

- Guarcello, E.; Colombini, S.; Paolasso, I. Formare alla complessità attraverso l’uso dell’immagine. In Un’ipotesi formativa basata sulla geografia emozionale. In Proceedings of the National Conference Assimss “Governare la complessità”, Roma, Italy, 3 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zonca, P.; Esplorare la professionalità dell’educatore di nido: L’ipotesi di una mappa geografica per rappresentarla. Metis 2016, VI. Available online: http://www.metisjournal.it/metis/anno-vi-numero-2-122016-cornici-dai-bordi-taglienti/192-saggi/905-esplorare-la-professionalita-delleducatore-di-nido-lipotesi-di-una-mappa-geografica-per-rappresentarla.html (accessed on 6 November 2017).

- Bruner, J. Verso Una Teoria Dell’Istruzione, 1st ed.; Armando: Roma, Italy, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotskij, L. Pensiero e Linguaggio, 1st ed.; white"> Giunti: Firenze, Italy, 1966; ISBN 8809200632. [Google Scholar]

- Trinchero, R. Manuale di Ricerca Educativa, 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2002; ISBN 8846441583. [Google Scholar]

- Sclavi, M. Arte di Ascoltare e Mondi Possibili. Come si Esce Dalle Cornici di Cui Siamo Parte, 1st ed.; Bruno Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 2003; ISBN 8842490210. [Google Scholar]

- Mortari, L. La Pratica Dell’Aver Cura, 1st ed.; Bruno Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 2006; ISBN 8842498823. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Division of Mental Health. In Life Skills Education for Children and Adolescents in Schools, 2nd ed.; Document No. WHO/MNH/PSF/93.7A.Rev.2.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zonca, P.; Guarcello, E. A Map on the World of Professional Identity. Visual Narration for Education and Care Workers. Proceedings 2017, 1, 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090869

Zonca P, Guarcello E. A Map on the World of Professional Identity. Visual Narration for Education and Care Workers. Proceedings. 2017; 1(9):869. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090869

Chicago/Turabian StyleZonca, Paola, and Emanuela Guarcello. 2017. "A Map on the World of Professional Identity. Visual Narration for Education and Care Workers" Proceedings 1, no. 9: 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090869

APA StyleZonca, P., & Guarcello, E. (2017). A Map on the World of Professional Identity. Visual Narration for Education and Care Workers. Proceedings, 1(9), 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090869