Abstract

Architecture communication tools have been implemented in recent history by strategies and narrative artifices imported from cinema, comic, photo-journalism and infographic. The architect has integrated the traditional encoded drawing with more extensive narrative artifacts to expand the basin of its interlocutors and to describe underestimated aspects of architecture and design process. Through the illustration of recent significant experiences, this paper intends to highlight the great variety of images that can be attributed today to architecture and the lack of proper attention on this production by Visual Studies.

Keywords:

architecture; storytelling; media; communication; representation; visualization; visual studies; images; video; illustration 1. Introduction

The need to make architectural material accessible to a wider audience than the specialised circles of field professionals has made it so that architecture, in revising the ways it communicates and expresses concepts, is increasingly treated in keeping with the communication devices used in other languages and manifestations of Science and Art, with a particular emphasis on the new languages of the electronic era.

For some time now, architecture has ceased to involve three single entities—the designer, the client and the construction site—and has become of keen interest to those who perceive it, use it and live it in a wide variety of ways.

‘It is no longer a case, as it has been up until even just recently, of understanding architecture and communicating its value; rather it is a new, expanded way of perceiving it, where architecture becomes, in itself, part of communication, a tool of and for communication.’[1]

Nevertheless, the codified representation of architecture reveals all its limitations when it has to explain a process, an adaptation, interactions and content that cannot be measured in geometric or metric terms.

After all, architecture is the product of a complex process that we cannot claim to be entirely represented by its technical sketches or traditional views, much less by the profile and presence of completed design projects.

Increasingly, there is a need to illustrate the process that led to a design idea in modern-day architecture, a process that is always attempting to balance formal instinct and technical expertise, and has always been sensitive to the conditions that arise from the dialectic relationship with commissioning clients.

With the myriad different solutions that many established professional firms propose, the process of defining design strategies leads to the identification of its individual creators, rather than its belonging to a well-defined style. Hence the need to find forms of conceptual—as well as academic—representation that can explain that process to an audience made up of both specialists and the common man so as to bring an industry like architecture, considered to be elitist, closer to a wider public.

In constructing architecture, both on the level of a single building and on an urban scale, various different players and influences are involved. These single out the political, social and economic conditions that affect a design. The patient dialogue that an architect conducts with local authorities, commissioning clients or even the entire resident population is typical of this, when citizens are asked to participate in choices of collective interest, expressing their opinions on the processes that transform their city and their district.

Such external circumstances, which concern players and interested parties—where the possibility of turning a design into reality often depends on their persuasive powers—are joined by a more internal influence. Here the genesis of project choices and their evolution are particularly involved. The sketches, diagrams, models as well as the miscellaneous visual and photographic collections that have always been put together by designers in order to help them convey ideas and suggestions, as well as quote references that can back up their decisions, are traces of this.

Once completed, a design cannot merely be validated on the basis of the functional solutions it offers. Architecture feeds off images and ‘produces images’. In marking and changing cities and territories, architecture is also perceived thanks to the images that its mere presence creates, whether it is as important as a new, incisive landmark or whether it manages to blend in with its surroundings. What we are talking about are images that will remain the heritage of a much wider audience than its immediate beneficiaries for some time. Buildings that have been turned into icons by thousands of photographic images—the media’s true sounding board—have also often become sought-after venues for communicating advertising messages or symbols used to identify not only geographic and economic circumstances, but political leanings as well.

In order to communicate and visualise these, as well as other aspects of architectural design projects, the representational tools that architects have at their disposal have been forced to borrow strategies and narrative devices imported from the cinema, cartoons, photojournalism and infographics, even hybridising these different genres. Architects have therefore had to apply—with the help of film directors, photographers and graphic designers—their limited, traditional methods of communication, fine-tuned over the centuries in order to communicate in an almost exclusive manner with their commissioning clients and the construction site.

Architects such as Gropius, Le Corbusier, Charles and Ray Eames and Yona Friedman all turned to the cinema, to name a few. The utopian visions of Archigram, Superstudio and Lebbeus Woods turned to the language of cartoons, as well as concrete proposals such as those of Rem Koolhaas, Herzog & de Meuron and Jan Neutelings. The masters of Functionalism, not to mention post-modernists and neo-avantgardists, resorted to photo collage, to the point where a visual strategy that came about as a Dadaist challenge has been raised to the dignity of a truly sophisticated compositional strategy in architecture. Infographics have taken over in the attempt to highlight data or parameters upon which the rationale behind a design is based, while photographic narratives punctuated by cartoon bubbles, like graphic novels, are increasingly used in the printed pages of books and magazines when discussing the opinions and daily work of star architects.

This ‘transmedial’ use of images can also be noted in international design competitions where architects are increasingly asked to narrate the logic behind their proposals on video, rather than producing detailed drawings illustrating the technical and construction solutions chosen. This has led to the evolution of the role of draughtsman into the specialised figure of ‘visual artist’, who is asked to dramatise the story behind a design, handling its narration and highlighting its visual characteristics, working digitally with filmmaking, editing and post-production software.

Modern studies of visual culture seem to have remained indifferent towards this mishmash of images created for architecture and generated by architecture itself, or at best seem unable to place or interpret them in any precise fashion. What we are dealing with are images that are hard to pigeonhole in the more usual branches of visual studies, despite the fact that such studies are based on the assumption of not being limited to artistic production alone, but rather ‘on the ability of analysing any type of image that could be considered culturally significant’ [2] (p. 38).

2. World Images

In 1995, a ‘massive book’ was published by the Dutch firm OMA (the Office for Metropolitan Architecture). It covered 20 years of designs arranged in order of size, hence the title S,M,L,XL [3]. Compared to traditional architectural monographs that usually aim to arrange the results of the research carried out by a firm or an individual designer in chronological order, S,M,L,XL aims to show how the process of designing and creating architecture is a ‘chaotic adventure’ due to the ‘interference’ of a constant arbitrary element introduced by the unknown factors contributed by commissioning clients, individuals and institutions. Its description of architecture and its conceptualisation makes room for a journalistic narrative with a ‘social’ intent, if you will.

‘To restore a kind of honesty and clarity to the relationship between architect and public, S,M,L,XL is an amalgam that makes disclosures about the conditions under which architecture is now produced […] On the basis of contemporary givens, it tries to find a new realism about what architecture is and what it can do.’[3] (p. xix)

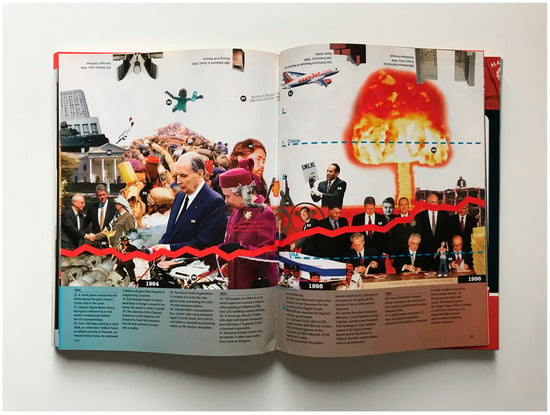

In the over 1300 pages that make up the book, text and, above all, images have been expertly laid out by the Canadian graphic designer Bruce Mau, giving the impression of a TV channel surfing experiment that stimulates free associations of meaning. There is no set page layout. Each page is arranged like a freestanding episode. The text uses different fonts of different sizes, creating columns, occupying entire pages, running from one page to another and overlapping the images like titles appearing across a television screen. Design projects are narrated using a cinematic dimension, obtained with the sequencing, juxtaposition and assembly of different kinds of materials borrowed from different media and sources, thus highlighting the complexity of these processes. Sketches, photographs of finished objects, photo collages, images of studio models, pictures taken from newspaper articles and advertising, cartoons, diagrams and rendering, i.e., ‘world images’, all contribute to documenting the successes and failures of a design studio that wishes to prove that it is at the mercy of the market economy and globalisation. ‘Form is content’ in S,M,L,XL—as Bruce Mau says, paraphrasing Marshall McLuhan.

Figure 1.

Pages from the book S,M,L,XL edited by OMA Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau (The Monacelli Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995).

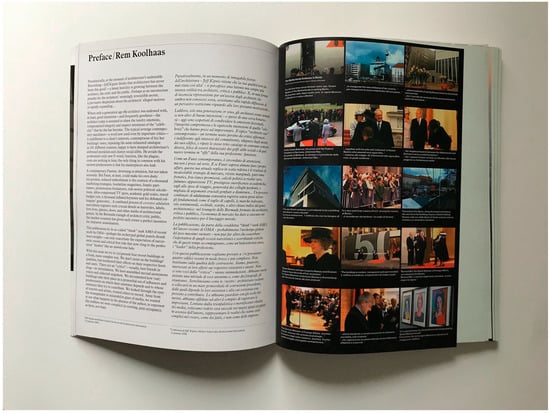

In the wake of the media and commercial success obtained by S,M,L,XL, Rem Koolhaas—OMA’s deus ex machina—returned to this formula once again in 2004 with the publication of Content [4]. The ‘tale’ of his most recent designs and completed projects is once again entrusted to a thick, dense sequence of images and text where, together with the work done by the OMA firm, the book also presents the work carried out by the mirror image AMO think tank—established to provide strategic input expanding the remit of architecture into the realm of the virtual including media, fashion, communication and information – set up by Koolhaas to introduce communication strategy and image development as true passe-partouts that can make the role of architects in society more accessible and understandable to a wider audience. Content editorially presents itself as halfway between a book and a magazine, where photographers, illustrators, cartoonists, journalists and columnists contribute even critical opinions. The design strategies that OMA has fine-tuned are presented in the form of patents in order to stress their universality; infographics illustrate the different social contexts that architecture is called upon to interpret; photo collages are used to compare modern-day architecture with news reports, political figures, works of art and icons of sport and pop and rock music. In Content, the brainstorming that architects subject themselves to in the age of globalisation is dramatised in the form of a dense ‘diorama’ of images that explain the political, economic, social and cultural context that shapes modern-day architecture.

We also find this use of ‘world images’ in a third book published by AMO/Rem Koolhaas. In Post-Occupancy [5], Lev Manovich’s observations regarding the prevailing languages of the new media seem to be wholeheartedly espoused and applied.

‘After the novel, and subsequently cinema, privileged narrative as the key form of cultural expression of the modern age, the computer age introduces its correlate—the database. Many new media objects do not tell stories; they do not have a beginning or end; in fact, they do not have any development, thematically, formally or otherwise that would organize their elements into a sequence. Instead, they are collections of individual items, with every item possessing the same significance as any other.’[6] (p. 27)

Figure 2.

Pages with a photo collage from the book Content edited by AMOMA/Rem Koolhaas (Taschen: Köln, Germany, 2004).

In Post-Occupancy, four buildings recently produced by the OMA firm are presented in a new form, i.e., using collections of images and comments that record the effects of these buildings on their visitors and users.

‘There are no “critics” […] We have assembled myriad anonymous voices and collected snapshots. […] We looked through the eyes of tourists and artists, trusted others to record. Away from the triumphalist or miserabilist glare of media, we wanted to see what happens in the absence of the author, to represent the realities we were complicit in creating, post-occupancy, as facts, not feats.’[5] (Preface, s.p.)

Collecting images from the Internet’s database, the book combines stills from television reports and documentaries on these buildings; professional photographs placed alongside amateur snapshots taken by tourists and visitors, which can be sourced from the main photographic databases found online. Technical drawings such as floor plans and sections are presented in several overlapping layers merely to illustrate the ‘anatomy’ and complexity of the designs—perhaps taking it for granted that such forms of representation will only be understood by a handful of people. Newspaper cuttings recording the official inauguration of the new buildings are placed alongside cartoons that mock OMA’s forms of architecture. Interviews that ask users of these buildings what they think are placed alongside anamorphic devices that provide 360° photographic views of interiors and exteriors. What we have here is a modern form of computational narrative where each reader is invited to put together different kinds of material in order to create their own personal meaning.

Figure 3.

Pages from the publication Post-occupancy edited by AMO/Rem Koolhaas (Domus d’autore, 2006, 1).

This way of working on images, involving an uninhibited layout ‘exploited for its heuristic and hermeneutic impact’ so as to generate ‘friction’ [7] (p. 27) with unusual pairings, is now an integral part of modern-day visual storytelling, perhaps a descendant of the 16th and 17th-century Wünderkammer.

The journal Domus, in the years when it was directed by Stefano Boeri, also attempted to experiment with the universal language of images as if it were a new Esperanto. In issue No. 902 (April 2007), the content was solely presented in the form of images. Architecture and design projects, together with ‘essays’ on urban space, art and landscape were only presented using photographic images, pictographs, infographs and drawings. Even the titles of the articles and names of the authors were translated into images alone. References to the familiar digital search pages of Google Images and analogical versions in the Storia Visiva dell’Architettura Italiana (M. Savorra, editor. Mondadori Electa: Milan, Italy 2006–2007) contributed to formulating the question that gave rise to that issue of the journal: ‘Can we solely use images to construct sentences, arguments and thoughts, stealing the monopoly on knowledge from words?’

3. Photo Stories e Comic Books

In 2012, the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Cinisello Balsamo funded a project that focused on the popular narrative form of the graphic novel. This initiative resulted in two exhibitions and a conference on the subject, but there was also the opportunity to experiment with a different use for graphic novels. Marco Signorini’s pictures and Giulio Mozzi’s text were applied to the graphic novel narrative form to tell the story and raise awareness of the conditions in the towns of Sesto San Giovanni and Cinisello Balsamo, with their abandoned factories and stock of run-down areas waiting for a new identity. The graphic novel was distributed free of charge in public offices and cultural venues in the north of Milan, in the libraries and newspaper stands of the towns where the story takes place. Hence, a popular storytelling form like the graphic novel, which emerged in the post-war period to ‘tell love stories using stills’, was used to create a more immediate relationship between the media, the public and our understanding of the territory.

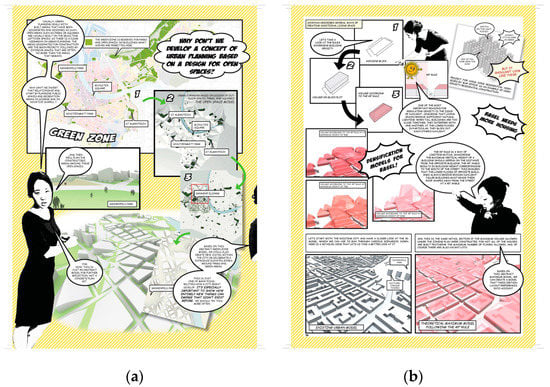

A similar media strategy had already been adopted as far back as 2009—using the comic book form—by the ETH Studio Basel research group—an urban research institute founded at ETH Zurich by the architects Roger Diener, Jacques Herzog, Marcel Meili and Pierre de Meuron to conduct urban research in the Region of Metrobasel. In this case, the complex transnational territory of Basel and its future potential was illustrated using a story portraying the adventures in the daily life of two main characters, Patricia and Michel. The results of research conducted on a scientific basis by the ETH Zurich urban research institute did not merely focus on the interpretation of the data that emerged from an analysis of the territory and the fine-tuning of design research. Their awareness of the importance of actively involving local people in an operation on an urban scale like that which was being planned, persuaded the research team to design an unusual form of communication—which we could define as ‘bottom up’—addressing residents as well.

Instead of the usual abstract technical visuals used in town planning (maps, histograms, infographs, etc.), the impressions gained and the proposals put forward by the research group are illustrated in the MetroBasel [8] comic book using a form of visual storytelling that draws on various different kinds of media: photography, illustrations, cartoons, photo stories and even technical drawings. During their one-week stay in Basel, the two main characters—Patricia and Michel—guide the reader using the distinctive features of this metropolitan region, illustrating the lifestyle of its inhabitants, the homes they live in, the various different economic industries that have contributed to shaping the city, information about transport and travel, the role of commercial spaces, schools and research institutes, as well as spaces set aside for leisure and entertainment. The potential that emerges from the interpretation of the city of Basel and its Swiss, French and German surroundings ends up outlining the future development that could affect MetroBasel and fosters the expectations of the resident-readers themselves who are asked to unravel the narrative.

Figure 4.

(a,b) Extract pages from the publication MetroBasel. A Model of a European Metropolitan Region edited by ETH Studio Basel (ETH-Bibliothek: Zurich, Switzerland, 2009).

For this Swiss research group, the comic book format was the perfect medium for presenting urban research because it allowed them to integrate the descriptive narrative with detailed background information in an accessible way.

‘While the abstract nature of urban research often finds little reception in the public realm, we serve to mitigate this perceived aloofness by mediating interest through an engaging comic-book narrative. Our intended goal is to attract as wide a readership as possible […]’[9]

This tendency to use ‘photo-stories’ to make issues raised by territorial design more accessible has also become a narrative device used in a journalistic way in trade journals, in order to guide the reader through modern-day buildings that sometimes seem, deep down, to belong to the world of cartoons rather than that of everyday experience. Guided tours of the Munich stadium designed by Herzog & de Meuron, of the BMW factory in Leipzig designed by Zaha Hadid and of the Dutch embassy in Berlin designed by OMA/Rem Koolhaas were presented in the form of photo-stories, with cartoon bubbles containing the opinions of journalists and designers, published in the journal Domus (‘Football Cloud: Una visita guidata al nuovo stadio di calcio di Monaco’, in Domus 881, May 2005; ‘Domus breaks the rules and (almost) shows a preview of BMW Plants by Zaha Hadid in Leipzig’ in Domus 880, April 2005; ‘Dutch Splash in Berlin: A tour of the new Dutch Embassy’, in Domus 866, January 2004). It is a narrative formula that has become so popular that it has been adopted as a true promotional tool by some of the leading figures in modern-day architecture to present themselves and their work in the same way a monograph would have done.

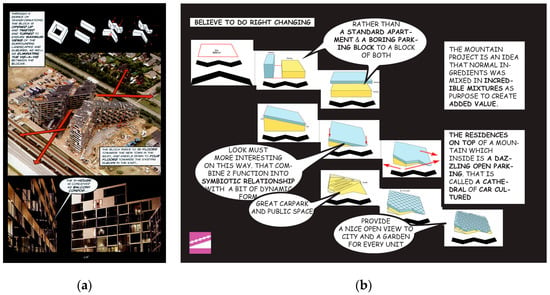

The publication Yes is More [10], which explores the work of the Danish architect Bjarke Ingels and his BIG studio, is a veritable manifesto of this genre. Bjarke Ingels has become one of the most popular architects of the younger generation thanks to his masterful, capillary use of media, which is matched by the increasing number of design competitions he has won. In Yes is More, the formal genesis of BIG’s design projects—whose visual impact seems to hark back to the world of cartoons and science fiction—is presented by Bjarke Ingels himself, portrayed as the main character in a comic book that guides the reader through the development of his ideas and forms, from the initial concepts up to analogue and digital views of his phantasmagorical buildings. In actual fact, a narrative of this kind ends up being more persuasive and convincing than the buildings themselves.

Figure 5.

(a,b) Illustrations from the book Yes is More: An archicomic on architectural evolution edited by BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group (Evergreen: Köln, Germany, 2009).

4. Video

The tendency to increasingly resort to forms of storytelling derived from cinema in the field of communication demonstrates how what Manovich called ‘a cinematic approach to the world’ is gaining ground. It is an approach that impacts on ways ‘of structuring time, of narrating a story, of linking one experience to the next’. The cinematic approach to the world has become ‘the basic means by which computer users access and interact with all cultural data’ [6] (p. 108).

The influence of cinematic language on the way architecture is communicated and on architects themselves is well-documented in history, with experiences conducted with documentary intent or propagandising aims. Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Charles and Ray Eames, as well as Italian architects such as Piero Portaluppi, Piero Bottoni and Ludovico Quaroni—to name a few—immediately found exciting connections between cinematic experience and design practice – as widely treated by Vincenzo Trione in his book Il Cinema degli Architetti (Milan: Johan & Levi Editore, 2014). Above all, the film camera was seen as the ideal instrument for appreciating built spaces, offering spectators the impression of entering and moving around an architectural structure.

The practice of using video to demonstrate the way buildings are used is even closer to cinematic storytelling, once an architect stands aside and leaves the job of ‘interpreting’ buildings to their users. Even as far back as 1954, Giancarlo De Carlo’s short film Una Lezione di Urbanistica (written with the aid of Elio Vittorini) depicted all the discomfort experienced by people living in Functionalist houses, designed on Existenzminimum subsistence dwelling principles.

More recently, the film directors Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine have used the medium of cinema to test new narrative forms as regards modern-day architecture, its use and the way it is received by the public and its users. The series of films entitled Living Architectures is a collection of feature-length films where, instead of conveying the opinions of architects or critics, as is usual, the experience of normal people living or interacting with cold, sterile building design and iconic spaces of our time is given a voice.

‘“Living Architectures” is a series of films that seeks to develop a way of looking at architecture which turns away from the current trend of idealizing the representation of our architectural heritage.’(I. Beka and L. Lemoine)

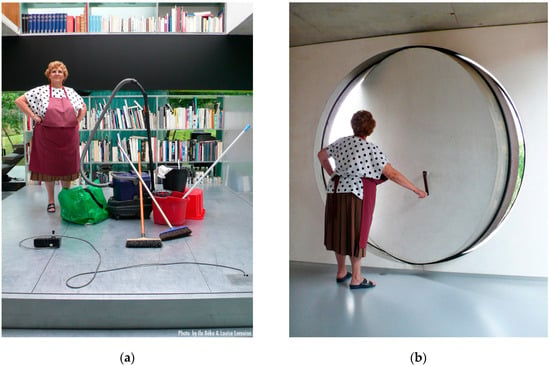

Figure 6.

(a,b) Photos by Ila Bêka e Louise Lemoine from their movie Koolhaas Housewife (2013).

This is Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine’s point of view as they lead us on a tour of OMA/Rem Koolhaas’s detached houses in Floriac by following the daily life of housekeeper Guadalupe Acedo (Koolhaas Houselife, 2013); they guide us as we explore Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum, designed by Frank Gehry, offering the unusual point of view of its maintenance workers who, wearing harnesses, are forced to climb the museum’s titanium exteriors that would otherwise be inaccessible (Gehry’s Vertigo, 2013); they present Richard Meier’s Tor Tre Teste church in Rome as seen by the inhabitants of the suburb next to it and that of its parish priest (Xmas Meier, 2013); they document the refectory at the Jean-Pierre Moueix winery in Pomerol, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, through the involvement of workers filmed during their lunch break (Pomerol Herzog & de Meuron, 2013); they spend 21 days recording the daily life of the inhabitants of Copenhagen’s ‘8 House’ grand residential complex, designed by BIG, offering us a video diary that presents an ironic and surprising glimpse of what it means to live with contemporary iconic architecture (The Infinite Happiness, 2015).

Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine’s films seem to have taken onboard the lessons of Jacques Tati when, with Mon Oncle (1958) and Playtime (1967), using the point of view of the common man—represented by the character Monsieur Hulot—he was able to capture our difficult relationship with the stylistic features of modernity imposed by architecture and design in the 1950s, better than any critical essay could have done. In the Living Architectures series, the cinematic screenplay is less important, as the narrative is entrusted to a collection of images and impressions, some of which are quite striking, edited with a documentary slant. Although Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine avoid the device of true paradox, they share Tati’s humorous and sometimes surreal vein, which sheds new light on architecture and its creators.

5. Cartoons

There is now a well-documented movement to resort to cartoons as a medium for communicating even serious content, such as design proposals, even in examples that can be found mentioned in books on the history of architecture. From the representatives of radical movements of the 1960s and 70s to exponents of contemporary architecture, cartoons have become a true communication tool that sometimes supplements codified architectural representations – as shown by the extensive repertoire in M. van der Hoorn’s book Bricks & Balloons: Architecture in Comic-Strip Form (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2012). After all, the very fact that cartoons are a low-definition medium makes them a form of ‘highly participatory’ expression and therefore strategically used due to their ability to reach a wide audience.

Nevertheless, the work of cartoonists and illustrators can also describe a factor that is always missing from an architect’s drawings: time.

Having been created and fine-tuned over time in order to describe a building through its geometric features and size values, or in order to simulate its ‘retinal imprint’ through views constructed from one single, stationary point of view, architectural draughtsmanship does not contemplate any graphic/narrative form. The dynamic perception of spaces as they are explored, the temporary nature of interiors and their furnishings, the life of those who live in buildings and leave a trace of memory that is sometimes more incisive than the buildings themselves, are all aspects that demand a time factor. Apart from cinema, only cartoonists and illustrators have the necessary visual storytelling instruments to tell what architecture and cities are really required to interpret: human dwelling.

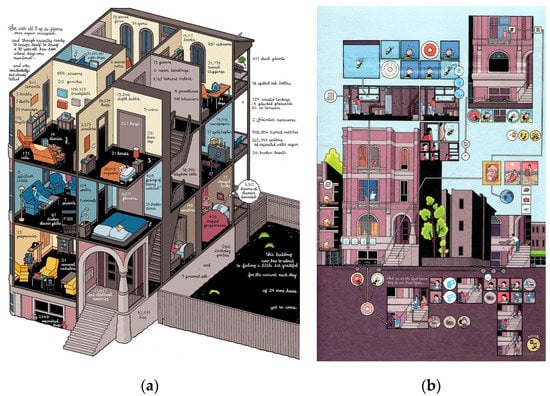

In Building Stories [11], the American cartoonist Chris Ware tells the story of those living in an old building in Chicago through fragments of memories. Shifting between the past, present and future and frequently resorting to the use of narrative windows borrowed from diagram infographs, Ware turns the building into the narrative’s main character.

Figure 7.

(a,b) Illustrations by Chris Ware from the graphic novel Building Stories (Jonathan Cape: London, UK, 2012).

The life of the people living in its spaces, the various plots that develop simultaneously in the apartments that interact with the building, all of this comes to life in illustrations built up in orthogonal and axonometric projections, almost as if the idea were to ‘scientifically’ represent the relationship between the physical interior of the spaces and the psychological interior of their inhabitants. Cataloguing the number of light bulbs used over time in each of the building’s three floors, the noisy radiators, the broken plates, drops of water, televisions used, books collected as well as the screams, births, broken hearts, lies told and parties that these rooms have witnessed, Chris Ware attempts to show how people remember spaces and not how spaces look to us.

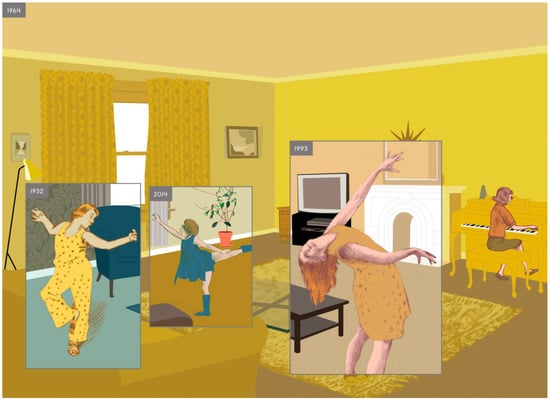

Another American illustrator, Richard McGuire, pursues a similar aim in his graphic novel Here [12] where he depicts his childhood living room over time, populated with images, memories and projections. McGuire shows us the same living room, from the same point of view, from 1907, the year of its construction, to 2313, with time windows that also reveal a glimpse of its immediate surroundings—starting in prehistoric times—and the building in which the living room is located. Apart from the constant presence of a fireplace and a window, the changing furniture in the room provides clues of time as it passes. While the three dimensions of the space remain unchanged, the fourth dimension, time, transports the reader forwards and backwards in time using parallel time windows that are connected to each other. Using an analogy with the desktop interface of a computer screen, where many windows can be opened and placed on top of each other, McGuire provides us with an example of ‘indirect meta-communicational narrative’, unhinging linear narration. As with Peter Greenaway’s experimentation with computational cinema, Richard McGuire challenges classic diachronic narrative, making it totally combinatorial. Thus the reader becomes an active participant, asked to construct the narrative by connecting the various different temporal planes.

Figure 8.

Illustration by Richard McGuire from the graphic novel Here (Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014).

These examples of communication using visual images, which could seem to have nothing to do with architecture, suggest instead that by resorting to a number of means, one can combine ‘the scientific’ description of traditional technical drawings—grouped as they are into ‘geometric types’ in individual representations—with a complex figurative text, shifting from a ‘descriptive portrayal’ to a ‘narrative sequence’ [13]. Cartoonists, illustrators, photographers, draughtsmen and film directors have all contributed to encouraging the creation of images of buildings, cities and human dwelling that has gradually shifted attention from the object to its perception, from the static and abstract nature of form to the variability of concrete and perceptible qualities that can be measured in their temporal aspects.

Author Contributions

A short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bradaschia, M. ‘Comunicare l’architettura’, Enciclopedia Treccani. Available online: http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/comunicare-l-architettura_%28XXI-Secolo%29/ (accessed on 21 May 2017).

- Pinotti, A.A. Somaini. Cultura Visuale. Immagini Sguardi Media Dispositivi; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 2016; ISBN 978-88-06-16099-9. [Google Scholar]

- OMA; Koolhaas, R.; Mau, B. S,M,L,XL; The Monacelli Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- AMOMA; Koolhaas, R. Content; Taschen: Köln, Germany, 2004; ISBN 3-8228-3070-4. [Google Scholar]

- AMO; Koolhaas, R. Post-Occupancy; Domus d’autore, Editoriale Domus: Rozzano, Italy, 2006; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Manovich, L. Il Linguaggio dei Nuovi Media; Edizioni Olivares: Milano, Italia, 2002; orig. tit. The Language of New Media, The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2001; ISBN 88-85982-61-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pinotti, A.; Somaini, A. (Eds.) Teorie dell’immagine. Il dibattito contemporaneo; Raffaello Cortina Editore: Milano, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-88-6030-214-4. [Google Scholar]

- ETH Studio Basel. MetroBasel. A Model of a European Metropolitan Region; ETH-Bibliothek: Zurich, Switzerland, 2009; ISBN 978-3-909386-90-1. [Google Scholar]

- www.manuelherz.com. Available online: http://www.manuelherz.com/metrobasel-comic (accessed on 1 June 2017).

- BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group). Yes Is More: An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution; Evergreen: Köln, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-83652-010-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, C. Building Stories; Jonathan Cape: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0224078122. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, R. Here; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0375406508. [Google Scholar]

- Anceschi, G. L’oggetto Della Raffigurazione; Etaslibri: Milano, Italy, 1992; p. 197. ISBN 88-453-0514-7. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).