Abstract

Monitoring social discourse about COVID-19 vaccines is key to understanding how large populations perceive vaccination campaigns. This work reconstructs how popular and trending posts framed semantically and emotionally COVID-19 vaccines on Twitter. We achieve this by merging natural language processing, cognitive network science and AI-based image analysis. We focus on 4765 unique popular tweets in English or Italian about COVID-19 vaccines between December 2020 and March 2021. One popular English tweet contained in our data set was liked around 495,000 times, highlighting how popular tweets could cognitively affect large parts of the population. We investigate both text and multimedia content in tweets and build a cognitive network of syntactic/semantic associations in messages, including emotional cues and pictures. This network representation indicates how online users linked ideas in social discourse and framed vaccines along specific semantic/emotional content. The English semantic frame of “vaccine” was highly polarised between trust/anticipation (towards the vaccine as a scientific asset saving lives) and anger/sadness (mentioning critical issues with dose administering). Semantic associations with “vaccine,” “hoax” and conspiratorial jargon indicated the persistence of conspiracy theories and vaccines in extremely popular English posts. Interestingly, these were absent in Italian messages. Popular tweets with images of people wearing face masks used language that lacked the trust and joy found in tweets showing people with no masks. This difference indicates a negative effect attributed to face-covering in social discourse. Behavioural analysis revealed a tendency for users to share content eliciting joy, sadness and disgust and to like sad messages less. Both patterns indicate an interplay between emotions and content diffusion beyond sentiment. After its suspension in mid-March 2021, “AstraZeneca” was associated with trustful language driven by experts. After the deaths of a small number of vaccinated people in mid-March, popular Italian tweets framed “vaccine” by crucially replacing earlier levels of trust with deep sadness. Our results stress how cognitive networks and innovative multimedia processing open new ways for reconstructing online perceptions about vaccines and trust.

1. Introduction

Social media has given voice to millions of individuals, who daily create [1,2,3], manipulate [4,5] and promote [6,7,8] specific perceptions about the online and real-world [9,10]. The present work quantitatively examines how social media framed the announcements of COVID-19 vaccines. Focus is given to the specific semantic frames [11,12] and emotional portrayals [11] made popular by social discourse on Twitter at the end of 2020. Given that a single popular tweet was liked by up to 495,000 users (i.e., the population of a medium-sized city in the USA), we assess online perceptions that reached massive audiences. Taking inspiration from other works using social media for monitoring perceptions and attitudes to COVID-19 [13,14,15,16], we adopt the recent framework of cognitive network science [17,18] to reconstruct the conceptual and emotional associations addressing COVID-19 vaccines in posts.

Through machine learning, network science and psycholinguistics, we give structure to vaccine-focused stances by representing them as interconnected sets of ideas, i.e., cognitive networks [9,17] of linguistic associations that mirror how words/concepts/ideas were syntactically, semantically and emotionally assembled in tweets. Contrary to black-box natural language processing, cognitive networks enable an immediate, transparent visualisation of how ideas were linked, framed and perceived through language [1,12,15,18]. This is crucial to understanding how debating COVID-19 vaccines can relate to distress signals [19,20], e.g., social users denouncing issues with vaccine distribution. Analogously, access to specific semantic/emotional frames can highlight negative attitudes of closure [10,21,22,23], e.g., conspiracy jargon that might critically hamper vaccination campaigns and public health.

We outline our methodology and quantitative results, including evidence for losses of trust, Trump’s administration and conspiratorial jargon, in view of relevant past approaches for COVID-19 infoveillance.

1.1. Reconstructing Perceptions with Artificial Intelligence and Complex Networks

The identification of people’s views on something is known as stance detection in computer science and psycholinguistics [24,25]. This task is key for understanding how conversations portray specific topics. For instance, are individuals in favour or against a given prescription about the current pandemic? Studying stances through language has been historically performed through human intervention, which involves a person reading text, reconstructing syntactic and semantic associations between words in the text and then classifying the result. Human intervention is clearly not sustainable when dealing with thousands of interconnected stances, as expressed in thousands and thousands of online social posts [16]. The advent of social media content gave voice to millions of internet users, a voice that reports stances of relevance for understanding how real-world events are debated online [8]. Towards this direction, computer and data science recently developed numerous approaches to stance detection, mainly powered by machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) [11,25,26]. Machine learning is usually highly accurate in detecting whether a stance is positive or negative [5,22,26]. However, it provides little information about the underlying interpretable structure of the stance. AI-based approaches are not able to interpret how conceptual elements are entwined in a given stance. Consequently, the experimenter cannot establish a link between how stances were perceived/connected and the classification result, resulting in black-box approaches [10,25].

The present work achieves stance interpretability by merging machine learning with cognitive networks [9,17,27,28], which are representations of how knowledge is connected and processed within the human mind [9]. Cognitive networks represent knowledge as associations between different concepts. These conceptual associations create networks of interconnected concepts that are far from being uniform. Let us focus on the example of syntactic associations, which generally specify the meaning of concepts, e.g., in the sentence “the pen is red”, the auxiliary verb “is” syntactically depends on “pen” and “red”, and it specifies a semantic feature of the concept “pen”. Extracting syntactic dependencies from text means harnessing the structure of knowledge specifying concepts within the text itself, and it can be performed automatically through universal syntactic parsing relying on artificial intelligence. Previous research showed that syntactic links between concepts extracted in this way can capture the most prominent concepts of a text, i.e., the keywords characterising the general topic of the text itself. In this way, extracting cognitive networks of syntactic relationships out of texts can provide crucial data for interpreting how individuals draw connections to associate and express different ideas. This mechanism provides interpretability to our analysis, which reconstructs how different stances are structured and interconnected in a set of documents (e.g., online posts) and thus gives associative structure to knowledge.

1.2. Innovative Contributions of This Work: Cognitive Networks Operationalise Semantic Frame Theory in COVID-19 Social Discourse with Text and Pictures

The main contribution of this work is introducing a multimedia approach, combining cognitive networks and machine vision to explore online perceptions of COVID-19 debates. Our approach thus strongly relates with stance detection but from a cognitive perspective, which operationalises semantic frame theory [12] and mindset reconstruction from content mapping [29,30,31,32]. Let us briefly discuss these related approaches. If cognitive networks capture the structure of conceptual associations between ideas, then how can such structure be quantitatively harnessed to perform stance detection? In cognitive science, semantic frame theory [12] indicates that meaning is attributed to individual concepts in language by means of syntactic/semantic relationships with other words. In this way, the meaning attributed to one concept can be reconstructed by checking which words are associated with it in the text. This list of associates is also known as a semantic frame [12], and it provides crucial information for understanding how concepts were described or mapped in specific texts. In other words, the connotation of “vaccine” denoted by an author might be reconstructed by checking which words were associated with it, e.g., “safe”, “useful”, “hopeful”.

Syntactic dependencies and semantic links thus provide key information for reconstructing the stance surrounding a given idea in terms of a network neighbourhood of concepts associated wtih a given word/idea coming from a mental lexicon [9,30]. In our approach, semantic frames are thus to be identified with network neighbourhoods [18]. Hence, the task of reconstructing meaning when reading texts can be operationalised by checking the content of specific network neighbourhoods of concepts linked to a target one. The creation of this map was originally introduced by Carley [31] as a technique known as “content mapping” and performed according to human coding, i.e., a human reader associating ideas in texts. This approach was evidently limited in processing small volumes of texts, but it was successfully applied to detecting different semantic frames about teamwork in engineering teams [32].

Our approach is a “hybrid” because it substitutes human coding in the act of generating maps of conceptual associations with artificial intelligence, leaving human intervention to the understanding of network neighbourhoods/semantic frames. For this automation, we adopt the framework of textual forma mentis networks (TFMN) [8,29], which use neural networks and WordNet to perform syntactic parsing and semantic enrichment, respectively. Textual forma mentis networks operationalise semantic frame theory by identifying how concepts/words are associated with each other in sentences. For example, one text may frame the “gender gap” as a challenge that can be tackled by celebrating women’s success in science, whereas another text may describe the “gender gap” in more pessimistic tones ([29]). Forma mentis networks have successfully highlighted how students and researchers perceived STEM subjects [18], how trainees changed their own mindset after a period of formal training [30] and have also identified key concepts in short texts [29].

We enrich TFMNs with emotional data, coming from validated psychological mega-studies and indicating which emotions are elicited by individual words (cf. the NRC Emotion Lexicon [8]). Through this data, we quantify which emotions populate a specific semantic frame and interpret emotional patterns/profiles in view of the semantic content of the frame itself, further innovating stance detection from an emotional analysis perspective.

Inspired by recent applications of machine vision for mental health [33] and COVID-19 monitoring [34,35], we use TFMNs to build different semantic frames in social media posts also containing pictures. This multimedia combination of text and images is further boosted by adopting machine vision algorithms that identify entities in pictures, namely people and face masks (cf. the facemask-detection Python package, available at https://github.com/ternaus/facemask_detection, accessed on 16 March 2022). We combine text and pictures within the same quantitative framework and perform comparisons between different categories of online content, e.g., do posts displaying people wearing face masks contain different emotional content compared to other posts?

We channel the above approaches towards understanding the crucial topic of COVID-19 vaccination campaigns. As outlined by several previous approaches [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], social media discussions can provide crucial insights into real-world phenomena. For instance, topic detection in time-evolving social discourse about COVID-19 displays significant correlations with environmental and health changes affecting massive audiences. Fluctuations of topics in social discourse can anticipate fluctuations in prominence levels of COVID-19 for up to 4 days, indicating how online discussions can integrate effective health monitoring (in agreement with other independent studies, cf. [35,38]). Investigating conceptual knowledge embedded in texts read by massive audiences is also insightful for understanding how humans emotionally react to text [39] and self-regulate their behaviour [40,41]. Massive outbreaks of news can distort the perception of a global pandemic, such as the COVID-19 one [37], and also influence vaccine hesitancy in individuals [36,40]. In particular, Steinert and colleagues [40] found via machine learning that reading messages conforming to users’ medical beliefs or hedonistic expectations boosted willingness to undergo COVID-19 vaccination. This link further underlines how understanding popular, i.e., highly read messages, is crucial to predicting or understanding health-related behavioural patterns during a pandemic. Importantly, [36] found correlations only in some European countries, underlining the importance of adopting language-specific frameworks. We follow this road by investigating popular tweets (see Section 2.1) either in English or in Italian.

It must be underlined that although the above works adopted a cognitive framework [36,39,40], none of them investigated cognitive networks of associative knowledge, e.g., how were words in the same topic linked with each other? We explore this research direction and extract insights from social discourse mapping vaccination campaigns along four main perspectives: Anticipation, logistics, conspiracy and loss of trust.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Twitter Dataset and Data Ethics

This work relied on a collection of 1962 unique popular tweets in English and 2413 unique popular tweets in Italian, gathered by the first author through Complex Science Consulting’s Twitter-authorised account (@ConsultComplex). Tweets were collected through ServiceConnect in Mathematica 11.3 (https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/ServiceConnect.html, accessed on 1 April 2022). Only tweets including the word “vaccine” or the hashtag #vaccine were considered. The flag “Popular” in ServiceConnect gave access to trending tweets as identified by the Twitter platform (https://help.twitter.com/en/using-twitter/top-search-results-faqs, accessed on 1 April 2022). As reported in the documentation, please notice that “Popular” works on identifying tweets with more views than median values over specific time windows. In this way, even tweets relatively poorly liked or re-shared but viewed in time windows many times can be considered “Popular” by the platform. Tweets were gathered between 12 October 2020 and 17 January 2021 and between 15 and 19 March 2021; time windows covering early announcements of vaccine availability and temporary suspension. English popular tweets were liked on average 19,800 times and with a median of 4210 times. This difference indicates a distribution of liked content critically skewed towards large values, \including tweets being liked between 20 and 495,120 times. English popular tweets were retweeted on average 3300 times and with a median of 897 times. A single popular tweet was shared between 13 and 57,821 times. Italian tweets registered lower values of liked content (920 mean, 215 median, 6 minimum and 12,359 maximum) and sharing (150 mean, 48 median, 2 minimum and 2043 maximum). Twitter IDs and additional information such as web links to pictures were also gathered and processed. After the temporary suspension of the AstraZeneca vaccine in several EU countries, including Italy, between 15 and 19 March 2021, we gathered an additional set of 228 popular tweets in English and 180 popular tweets in Italian focusing on the keyword “astrazeneca”.

Notice that the data adopted in this manuscript was not generated nor created by the authors but rather gathered from Twitter through the Academic Research Programme Track, which provided ethics approval for gathering tweets for mining online perceptions for the account @ComplexConsulting, through which we performed data mining. For more information on the ethics of Twitter’s Academic Research Programme Track, please see: https://developer.twitter.com/en/products/twitter-api/academic-research (accessed on 1 April 2022). Notice also that in our analysis we adhered to the tightest standard of the Declaration of Helsinki, producing visualisations and results protecting the anonymity and confidentiality of individual users. For the same purpose and in line with Twitter’s ethics policies, we only released the Twitter IDs of messages used here (see https://osf.io/ke6yz/, accessed on 20 January 2022), which supports the scientific reproducibility of our findings.

Notice that the geographic location of tweets was not available in Mathematica 11.3, making it impossible to distinguish tweets based on their country of origin (e.g., USA vs. UK). For each Tweet, statistics such as the number of retweets and the number of likes (at the time of the query) were registered.

2.2. Language Processing and Network Construction

The text was extracted from each tweet in the dataset with the aim of building a knowledge graph of syntactic, semantic and emotional associations between words, i.e., a textual forma mentis network (TFMN) [29]. Emojis in tweets were translated into words by using Emojipedia, which characterises individual emojis in terms of plain words. Hashtags were translated by using a simple overlap between the content of the hashtag without the # symbol and English/Italian words (e.g., #pandemic became “pandemic”). The resulting lists of words were then stemmed in order to get rid of word declination (e.g., “loving” and “love” represent the same stem “love”).

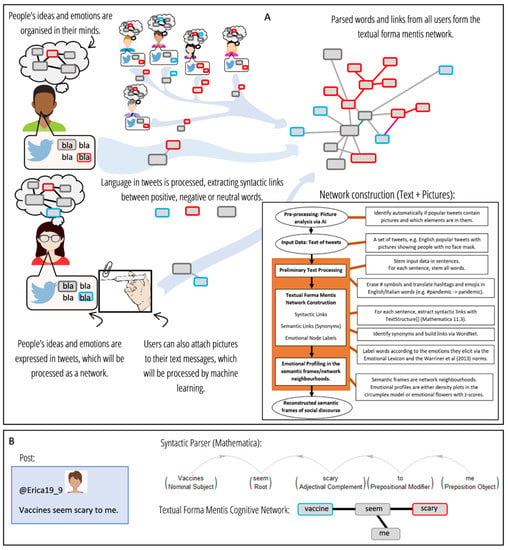

TFMNs combine cognitive information about how individuals associate concepts eliciting different sentiments, excitement and emotions in texts. Figure 1A (right) contains a flowchart explaining the different steps of network construction, as also reported in [29].

Figure 1.

(A) Infographics about how textual forma mentis networks can give structure to the pictures and language posted by online users on social media. Semantic frames around specific ideas/concepts are reconstructed as network neighbourhoods. Word valence and emotional data make it possible to check how concepts were framed by users in posts mentioning (or not) pictures showing specific elements (e.g., people wearing a face mask). A flowchart with the different steps of network construction is outlined too. (B) Example tweet being processed.

Word stemming was performed by using WordStem in Mathematica 11.3 (https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/WordStem.html, accessed on 16 August 2021) for English and SnowballC as implemented in R 3.4.4 for Italian. Stemming is particularly important for Italian, where nouns can be declined differently according to their gender (e.g., “dottoressa” and “dottore” both indicate the concept of a doctor). Stemming is important also in relation to the cognitive interpretation of a forma mentis network and knowledge representation in the human mind [9,42]. In fact, overwhelming evidence from psycholinguistics shows that different declinations of the same word do not alter the core meanings and emotions attributed to their stem [42]. For instance, “loving” and “loved” both activate the same conceptual construct related to love in language processing by individuals. Hence, these words should be represented with the same lexical unit in a cognitive network representing human knowledge as derived from text.

Knowledge representation was achieved through the building of a textual forma mentis network, whose main idea is to use machine learning to unearth the complex network of syntactic relationships between words in sentences [8]. This network is not explicitly observed in the text (i.e., we do not see links between words when reading this or other texts) but is mentally reconstructed to associate the nouns, verbs, objects and specifiers in a sentence in order to figure out the meaning of a certain message. Textual forma mentis networks (TFMNs) are knowledge graphs enriched with cognitive perceptions about how massive populations associate and perceive individual words. Connections between lexical units/concepts are multiplex and indicate: (1) syntactic dependencies (e.g., in “Love is for the weak” the meaning of “love” is linked to the meaning of “weak” by the specifier “is for”) or (2) synonyms (e.g., “weak” and “frail” overlapping in meaning in certain linguistic contexts).

Syntactic dependencies were extracted from each sentence in tweets via TextStructure[] in Mathematica 11.3 (https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/TextStructure.html, accessed on 16 August 2021), which relies on the Stanford NLP universal parser.

TFMNs were built starting from the text. After splitting the text into sentences, syntactic dependencies were detected in each sentence. For instance, “love is for the weak” gets decomposed in the following syntactic links: “love”—“is”, “is”—“for”, “for”—“weak” and “the”—“weak”. Those dependencies going through auxiliary verbs, prepositions and other stopwords were aggregated together into novel syntactic links between non-stopwords, e.g., “love”—“weak”. Meaning negators such as “not”, “no” and “n’t” were retained and added to the network of syntactic links between non-stopwords. This syntactic structure was semantically enriched with synonyms. Synonyms were identified by using WordNet 3.0 and its Italian translation [43]. The resulting syntactic/semantic network was enriched with emotional features attributed to individual words/nodes. Figure 1B contains an example tweet being processed. The sentence “Vaccines seem scary to me” is processed through the syntactic parser, the text is also regularised and words are endowed with valence/sentiment connotations (positive, negative or neutral). Notice that only words at a network distance shorter than T = 4 were linked. T was selected to preserve local but non-adjacent syntactic relationships in the text. Notice also how the stopword “to” was not preserved in the TFMN construction.

The main English TFMN included 2190 words and 19,534 links, whereas the Italian TFMN contained 1752 words and 24,654 links. The networks built in the aftermath of AstraZeneca’s vaccine temporary suspension included 410 words and 5953 links for English tweets and 233 words and 2390 links for Italian tweets, respectively. “Vaccine” had a network degree [17] of over 800 in the main English and Italian networks and of over 200 in networks based on popular tweets from the aftermath of vaccine suspension. Meaning modifiers such as negation words (e.g., “not” or “no”) were included in the network in order to keep track of meaning negation in emotional profiling. Words linked to negations were changed to their antonyms as extracted from WordNet 3.0 [43] and added to the semantic frame when computing emotional profiles. Valence, arousal and the emotions elicited by a given concept were attributed to individual words according to cognitive datasets.

2.3. Cognitive Datasets and Emotional Profiling

This study examined two datasets to reconstruct the emotional profile of language in texts: valence and arousal as coming from the psycholinguistic task implemented by Warriner and colleagues [44] and the Emotion Lexicon by Mohammad and Turney [11]. Both datasets summarise how large populations of individuals perceive individual words, either by rating of pleasantness (valence) or excitement (arousal) or by listing which emotions are elicited by such words (e.g., “disease” elicits the emotion of fear).

We used the valence and arousal data of English words in order to build 2D density histograms identifying emotional trends in a given portion of language. Valence and arousal act as coordinates in a 2D space, mapping several human emotions. This mapping between language and emotions is known as the circumplex model [45], and it has been successfully used in several psycholinguistic investigations [15]. The emotional states reconstructed through the Emotional Lexicon were: Joy, Sadness, Fear, Disgust, Anger, Surprise, Anticipation and Trust. Although the first six emotional states are self-explanatory, the last two identify emotional perceptions of either projecting one’s experience into the future (anticipation) or accepting norms and following behavioural codes imposed by others because of personal relationships or logical reasoning (trust) [46].

As a linguistic baseline for emotional neutrality, we adopted the interquartile range as computed from 13,900 English words in the Warriner et al. dataset [44]. Clusters of words falling outside of the neutrality range indicate the presence of an emotional trend in language [15]. We used the Emotional Lexicon in order to count how many words nE(w) elicited a given emotion E in a given semantic frame/network neighbourhood surrounding a concept w. We then compared each count against the expectation of a random null model drawing words at random from the overall emotional dataset. In each randomisation, we drew uniformly at random as many words as those eliciting for any emotion present in the network neighbourhood. After repeating 500 random samplings, we computed a z-score for each emotion E, namely:

where is the average random count of words eliciting a given emotion as expected in the underlying dataset (which features more words eliciting for some specific emotions and less concepts inspiring other emotions). is the standard deviation of the random counts. Z-scores higher than 1.96 (significance level of 0.05) indicate an excess of words eliciting a given emotion and surrounding the concept w in the structure of social discourse. We plot the emotional profiles as emotional flowers, where z-scores are petals distributed along 8 emotional dimensions. Petals falling outside of a semi-transparent circle indicate a concentration of emotional jargon stronger than expected from word-to-emotion mapping in common language (z > 1.96). This mapping is coded in the sampled dataset and preserved by uniform random sampling. Although we selected a 0.05 significance level and performed two-tailed statistical testing in our analyses, we focused on highlighting only emotional signals being stronger than random expectations in the current visualisations represented by emotional flowers. Emotional flowers are reported in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5. The valence-arousal dataset was translated from English into Italian through a consensus translation using Google Translate, DeepL and Microsoft Bing. For the Emotion Lexicon, the authors used the automatic translations provided by Mohammad and Turney in Italian [11].

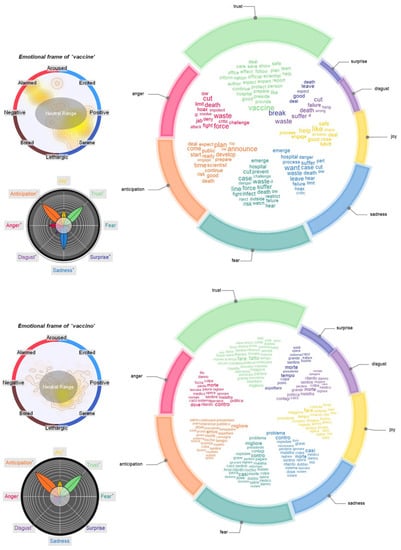

Figure 2.

Multi-language analysis of the emotional profiles of highly/less retweeted (left) or liked (right) tweets in English (top) and in Italian (low). Petals indicate z-scores and are higher than 1.96 when falling outside of the semi-transparent circle. Asterisks highlight emotions z > 1.96.

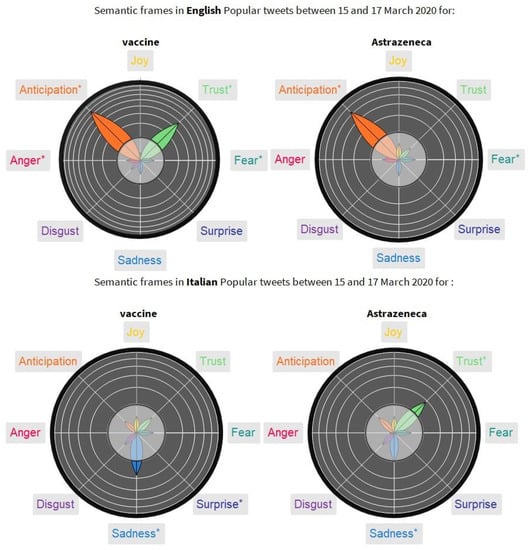

Figure 3.

Emotional analysis and word clouds of concepts in the semantic frame of “vaccine” (in English) and “vaccino” (in Italian). The circumplex model indicates how the neighbours of vaccine/vaccino populate a 2D arousal/valence space. The emotion flower indicates an excess of emotions detected in the semantic frame compared to random expectation. The sector chart reports the raw fraction of words eliciting a certain emotion. The word cloud reports the top 10% concepts with the highest degree of centrality which are associated with vaccine. The words are distributed according to the emotions they elicit. Asterisks highlight emotions z > 1.96.

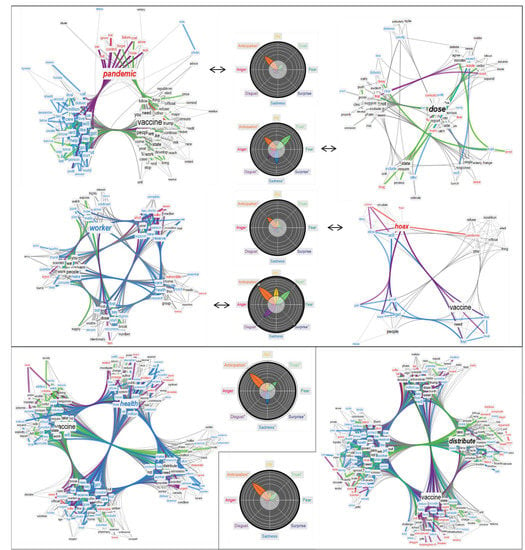

Figure 4.

TFMNs capturing conceptual associations in social discourse around “pandemic”, “dose”, “worker” and “hoax” (top) and around “health” and “distribute” (bottom). Positive (negative) concepts are cyan (red). Neutral concepts are in blue. Associations between positive (negative) concepts are highlighted in cyan. Purple links connect concepts of opposite valence. Green links indicate overlap in meaning. The emotional flowers indicate how rich the reported neighbourhoods are in terms of emotional jargon. Petals falling outside of the inner circle indicate a richness that differs from random expectation at α = 0.05. Each ring outside of the circle corresponds to one unit of z-score. Asterisks highlight emotions z > 1.96.

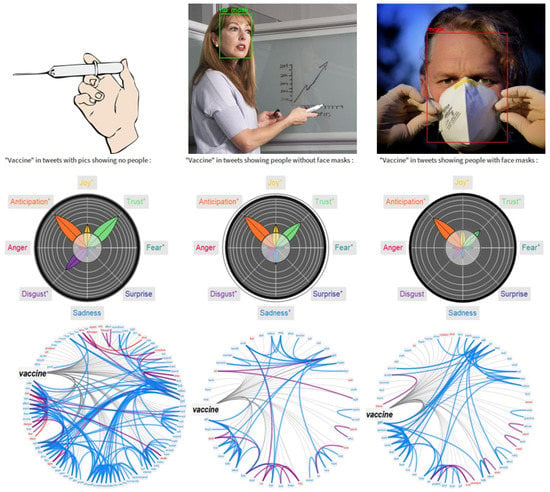

Figure 5.

Emotional flowers and valenced semantic frames for “vaccine” in those tweets, including pictures with: (1) no people (left), (2) people wearing no face masks and (3) people wearing face masks. On the top part of the panel, there are example pictures that were taken from Pixabay to demonstrate how the implemented Python library works. Bottom: Semantic frames reporting only negative and neutral words associated with “vaccine”. Asterisks highlight emotions z > 1.96.

2.4. Enriching Text Analysis with Multimedia Features of Tweets

Tweets can often include images that are associated with the text. These can be used to support the emotional content shared in the tweet and provide a visual medium that is complementary to the text. Here, we analysed the image data from tweets by means of: (1) additional text extraction from pictures via Google’s Tesseract library, (2) face and facemask detection through the RetinaFace AI package and (3) dominant colour analysis via picture processing. We used these additional machine vision routines to integrate or filter textual information from the above cognitive networks, providing a deeper understanding of the emotional content shared on Twitter.

We downloaded all images associated with English tweets, and we processed them using Google’s Tesseract-OCR Engine via the Python-tesseract wrapper (available at https://github.com/madmaze/pytesseract, accessed on 16 March 2022). This uses a neural network-based OCR engine to extract text from images. The resulting text from each processed image is then analysed using the language processing methods described above. It is important to highlight that not all images contain text, and in those cases, the output of the OCR engine returns an empty string. Manual verification of a sample of the text extracted from the images has shown a good accuracy of the algorithm (above 95%).

Face masks have been one of the trademarks of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the majority of countries worldwide introducing rules and recommendations on when and where face masks should be worn. Face masks have also often been a controversial topic, with polarised views from the general public on their perception in relation to personal freedom. As such, it is to be expected that a range of images associated with our tweets contain people wearing face coverings. This is of relevance to our analysis since the public perception and polarisation about face masks will undoubtedly influence one’s emotions about COVID-19 and vaccines.

However, the appearance and widespread use of face masks across the globe is mostly a recent phenomenon. Whilst face detection is a challenge that has been widely studied in the image processing community, detection of face masks has not been so prominent until recently. Detecting face coverings can be broken down into two different, sequential tasks: first, the algorithm has to detect the presence (and location) of faces within an image; then, for each detected face, the algorithm has to identify whether it is wearing a face mask.

To analyse the images in our data set, we used a recently developed face mask detection algorithm made available via the facemask-detection Python package (available at https://github.com/ternaus/facemask_detection, accessed on 16 March 2022). This offers a pre-trained algorithm that carries out both the face detection step and then assigns a probability to each detected face corresponding to the probability of there being a face-covering. The face detection step uses a recently developed face detector, known as RetinaFace [47,48]. This algorithm uses state of the art deep learning techniques to output the location, in terms of a bounding box, of each face detected in an image. A key strength of RetinaFace is its ability to detect faces at various scales, where faces can be present both at the front as well as in the background of an image. On top of the RetinaFace layer, the face mask detection step uses a pre-trained set of deep neural networks to output a probability value for each face detected by the RetinaFace step. Consistent with the recommendations in [47], probability values larger than 0.5 correspond to faces that the algorithm detected as wearing a face mask because the binary classifier assigned a probability of there being a face mask that is higher than the probability of there not being a face mask.

In our analysis, we process all images, and, for each image, we collect the number of detected faces by the RetinaFace layer, as well as how many of those faces have been assigned a probability larger than 0.5 of having a face mask. Note that we include in this analysis all images, regardless of whether they contain any text or not. This is because we have observed that some images contain text overlayed on top of a normal image, which in some cases contains faces and masks. Therefore, the face mask detection step is applied to all images in the data set of English tweets.

Finally, it is worth highlighting that, whilst manual inspection of the results of the face and mask detection step show very good accuracy, there are undoubtedly some cases in which this method fails to identify all faces or masks correctly. Whilst to be expected, such a limitation must be kept in mind when drawing conclusions from the results of our analysis.

3. Results

This section outlines the results of the analysis of popular tweets in terms of: (i) prominent concepts in social discourse captured by the frequency of occurrence and network centrality, (ii) focus on the emotional-semantic frames of “vaccine” and “vaccino” in social discourse, (iii) other semantic and emotional frames of prominent concepts in social discourse, (iv) behavioural comparisons of tweet sharing and liking depending on the emotional profile of posts and (v) picture-enriched analysis of online language.

3.1. Prominent Concepts Captured by Frequency and Network Centrality

This part of the study focused on identifying the key ideas reported in social discourse about the COVID-19 vaccine. Table 1 provides the 20 top-ranked concepts identified through word frequency and degree in the TFMN. Word frequency identifies how many times a single word was repeated across popular tweets and was potentially read by users. Degree counts how many different syntactic/semantic associations were attributed to a given concept and captures in the textual forma mentis network semantic richness, i.e., the number of connotations and semantic associates attributed to a single word [15,17].

Table 1.

Top-20 key concepts in the English (left) and Italian (right) corpora. Words are ranked according to their degree in textual forma mentis networks and their frequency in the original tweets. Italian words were translated into English for easier visualisation.

As highlighted in Table 1 (left), English popular tweets featured mostly jargon relative to the idea of “people receiving their first dose of vaccine”. This pattern was consistent between the ranks based on word frequency and semantic richness/network degree, respectively. These prominent words and additional key jargon related to the semantic sphere of time (such as “week”, “now” and “when”) together indicate a social discourse dominated by a projection for the future, relative to the logistics of vaccine distribution. Network degree also identified Trump as a key actor of popular tweets. Differently from word frequency, semantic richness highlighted how “workers” and “work” were prominently featured in popular tweets.

The Italian social discourse also featured key words related to people receiving their first dose of the vaccine. Key actors of social discourse in the Italian twittersphere were Pfizer and Moderna. Italian users mentioned medical jargon (e.g., “doctor”, “virus”, “effects”) more prominently than English speakers, in terms of both semantic richness and frequency. As in English, Italian discourse was also strongly dominated by words related to the semantic sphere of time, including prominent words like “time”, “hour” and “day”.

The above rankings indicate how social discourse in popular tweets about the COVID-19 vaccine were prominently projected toward future plans for dose distribution. According to the above simple semantic analysis, it can be postulated that the specific semantic frame of “vaccine” (and “vaccino” in Italian) also should be populated by emotions such as anticipation of the future.

3.2. Semantic Frames for “Vaccine”: Logistics, Content Sharing, Trump and Hoaxes

Social discourse in popular tweets about COVID-19 vaccines was strongly projected toward future plans for dose distribution. Both English and Italian tweets were dominated by jargon mixing “time”, “people” and “doses” (see Table 1).

To test how users reacted to emotional content in popular tweets, we studied the emotional profiles of highly/less-retweeted and liked messages based on medians. As reported in Figure 2, in English, highly retweeted or liked tweets contained language with an emotional content drastically different to the one embedded in less shared or liked content. An excess of sadness, joy and disgust characterised highly retweeted text messages, emotions absent in popular yet less frequently retweeted content. These results indicate an emotional interplay between content sharing and the tendency for users to retweet content.

What can be said about the specific semantic frames connecting these concepts to “vaccine”? Figure 3 focuses on the semantic frame surrounding “vaccine” in both English (top) and Italian (bottom) popular tweets. Both the circumplex model and the emotional flower (relying on different datasets, see Section 2.3) agree in indicating a polarised emotional profile of “vaccine” in popular tweets, concentrating on both positive/calm and negative/alerted emotional states. Anticipation of the future was the strongest emotional state populating the semantic frame of “vaccine”. However, the petals/z-scores falling outside the rejection region (white circle) also indicate a concentration of words eliciting trust and joy, but also anger, disgust and sadness. This indicates an emotionally polarised social discourse, as also evident from the word cloud in Figure 3 (top).

We delved more into the analysis of prominent concepts linked with “vaccine”, such as “health” and “distribute” (see Figure 4). Semantic frames are identified as network neighbourhoods and organised in communities of tightly connected words by the Louvain algorithm [17,49]. Discourse surrounding “health” was mostly dominated by syntactic/semantic associations with other positive jargon, featuring both: (i) actors of the health system (e.g., doctors, hospitals, volunteers) and (ii) aspects of vaccine delivery and administration. Popular tweets importantly linked vaccine distribution with vulnerable groups and mentioned the urgency of suitable plans for administering the vaccine despite the current crisis. These tweets also drew conceptual associations between “health” and “racism”, underlining the necessity of fair measures of health provision. The overall emotional profile of all the above aspects was dominated by anticipation, but also sadness (related to the difficulties of the current crisis) and trust towards the health system, its actors and its supporters, such as countries, nations and science.

Popular tweets were less positive when framing the specific concept of “distribute”, whose semantic frame was mostly populated by anticipation of the future. Institutions, administrations and nations (e.g., “president”, “Trump”, “administrate”) were tightly connected with concepts related to the semantic spheres of speed and time (e.g., “week”, “month”, “speed”, “warp”). This represents additional evidence that popular tweets about the COVID-19 vaccine underlined the need for a quick administering of vaccine doses.

A shift into the future is seen in other semantic frames, see Figure 4 (top). Whereas previous investigations reported semantic frames for “pandemic” filled with negative emotions [15], when discussing “vaccines”, “pandemic” underwent a valence shift and was framed along overwhelmingly positive jargon, featuring concepts such as “care”, “create”, “live” and “shield”. Other noticeable emotional/semantic patterns are:

- The associations attributed to “dose” identified aspects such as “delay”, “trial”, “waste”, “fear” and “conspiracy”, highlighting concern about the validity of a dose of vaccine.

- Sadness around “workers” had as semantic associations “vulnerable”, “expose”, “funeral”, “essential”, “suffer” and “severe”, indicating how popular tweets highlighted the importance for exposed workers to receive a vaccine.

- The above trend co-existed with positive emotions originating from celebratory jargon (“thanks”, “celebrate”), identifying the importance of workers during the pandemic.

Whereas Italian popular tweets did not feature jargon related to conspiracy theories, English popular tweets provided a rather highly clustered network neighbourhood for “hoax”, devoid of negations of meaning and featuring mostly jargon related to the future. Associations of “hoax” with ideas such as “censor”, “pandemic” and “vaccine” indicate a concerning portrayal of conspiracy theories within the considered sample of popular tweets. This represents quantitative evidence that conspiracy theories revolving around the COVID-19 vaccine were capable of reaching large audiences online through highly shared and liked (i.e., popular) tweets.

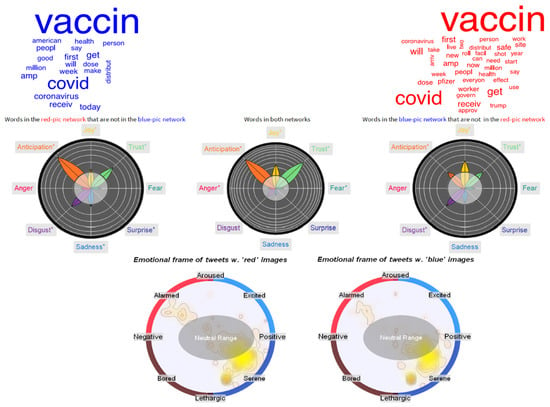

3.3. Extracting the Emotional Profiles of Face Masks with Machine Learning

In addition to text processing, we enriched our analysis with an investigation of the multimedia content promoted in popular tweets. After a dominant colour analysis (see Appendix A), we investigated the language of tweets containing images of people wearing a facemask. We built three TFMNs, each based on one of the following corpora of tweets: (1) posts including pictures of no people, (2) posts including pictures of people wearing no face masks and (3) posts including pictures of people wearing face masks.

The emotional profiles of “vaccine” contained in these three categories of multimedia are reported in Figure 5. Different emotions are found to populate the semantic frame of “vaccine” across these three categories. The language of popular tweets, including pictures with no people, is strongly polarised between trust/joy and disgust, emotions that are absent in popular tweets portraying people.

Tweets showing people wearing face masks corresponded to an emotional profile for “vaccine” different from the one of tweets showing people without masks. Pictures showing the full face of a person were accompanied with more trustful and slightly more joyous language—when associated with the idea of the vaccine—in comparison to the messages accompanying tweets with people wearing face masks. No difference was found in terms of anticipation, which permeates all the considered semantic frames of “vaccines” in Figure 5. The combination of anticipation, trust and joy in popular tweets with people wearing no face masks is a marker for hopeful emotional states, projected with positive affect into the future. This pattern is confirmed by the association between “vaccine” and “hope” in the respective semantic frame (see Figure 5 bottom). This hopeful framing vanished in the language of messages reporting people wearing face masks.

3.4. Aftermath of AstraZeneca’s Suspension: Loss of Trust in the Italian Twittersphere

On 15 March 2021, several European countries, including Italy, temporarily suspended the use of the COVID-19 vaccine developed by AstraZeneca, following sparse reports of serious side effects.

Figure 6 reports the emotional profiles of “vaccine” and “astrazeneca” in popular tweets gathered in the next few days after the suspension. In comparison with the popular perceptions observed in December 2020 and in January 2021, as summarised in Figure 3, the temporary suspension of the AstraZeneca vaccine had drastic effects on social discourse in the Italian twittersphere but not in the English one.

Figure 6.

Emotional flowers for “vaccine” and “astrazeneca” in popular tweets gathered after the suspension of the AstraZeneca vaccine in several EU countries in mid-March 2021. These results should be compared with the emotional profiles reported in Figure 2 and relative to the months before the suspension. Asterisks highlight emotions z > 1.96.

Popular English tweets still framed the idea of the vaccine along strong signals of anticipation for the future and trust. Trust was found in the semantic frame of “vaccine” but not with regards to the syntactic/semantic associates of “astrazeneca”, indicating a potential shift in trust between the abstract concept of a COVID-19 vaccine and the concrete one by AstraZeneca as described in popular tweets.

A more drastic shift in the emotions toward vaccines was found in the Italian twittersphere. By comparing Figure 3 (bottom) and Figure 5 (bottom) one notices how trust, joy and anticipation expressed by Italian users when mentioning “vaccine” in December and January vanished completely in the aftermath of the AstraZeneca temporary suspension in mid-March 2021. Positive emotions disappeared from the semantic frame of “vaccine” and were replaced with a weak signal of sadness, indicating concern as expressed by Italian users in popular messages.

4. Discussion

This work investigated social media language around COVID-19 vaccines. Popular tweets were found to portray mainly logistic aspects of vaccine distribution, polarised between trust/hope and sadness/anger. Frequent and semantically rich [9] concepts of social discourse were relative to the necessity for people to receive their first dose of vaccine as soon as possible despite the issues of administering massive amounts of vaccine. The hopefulness surrounding “astrazeneca” vanished completely after that vaccine was suspended temporarily in mid-March 2021, with repercussions of vaccine hesitancy [22,50]. These patterns underline strong interplays between the emotional content of popular tweets, their portrayals of vaccination campaigns and their overall diffusion among massive populations. Let us briefly discuss these results together with past relevant approaches.

Almost no emotional polarisation [51] was found in the semantic frame of “vaccine” in Italian, where an excess of positive emotions like joy and trust were found, in addition to anticipation. According to Ekman’s atlas of emotions [46], these basic emotions in language can give rise to nuances such as positive expectations for the future, i.e., hope.

A key innovation of our approach is combining cognitive networks of linguistic associations [17,29] together with pictures and AI-based methods of image analysis [47,48]. It must be noted that previous works have already combined machine vision and text analysis in mental health assessments (cf. [33]). However, to the best of our knowledge, these studies did not combine cognitive networks and picture analysis within the context of COVID-19. This synergetic combination is a key point of innovation in our approach. Popular English tweets showing no pictures of people were found to frame the idea of “vaccine” along with contrasting emotions of trust and disgust, debating side effects and ways to mitigate the impact of COVID-19.

Language accompanying tweets with people wearing a face mask exhibited almost no signal of trust or joy in the semantic frame of “vaccine”, differently from messages including pictures with people wearing no face mask. Although co-occurrence does not imply causation, it must be noted that the adoption of face masks in public places has been met with mixed results (for a review, see [52]) by most Western countries. Masks hinder expressiveness and can create discomfort if worn for long times, but there are also additional psychological elements. Recent studies showed how face masks became strongly associated with negative concepts, such as sickness and disease, in the cognitive perception of the COVID-19 pandemics [23]. By merging pictures and social discourse, our results indicate that the overall perception of people wearing face masks is biased, i.e., poorer in terms of trust and joy when compared to common portrayals of people wearing no face protection.

We also identified a behavioural tendency for English users to share more emotionally extreme content. Our findings indicate that also negative, inhibiting emotions such as disgust can amplify content sharing while sadness inhibits endorsement of online posts.

Our approach identified concerning links between vaccines and conspiratorial jargon. Conceptual associations between hoaxes and vaccines have been observed in many other studies [22]. However, in this case, these associations were found in popular messages and not in borderline peripheral content, such as the content produced by malignant social bots [1,6]. A negative framing of vaccines in terms of hoaxes driven by popular messages to large populations could self-evidently have negative consequences for the vaccination campaign. A recent study from cognitive neuroscience found that conspiracy-like misinformation can decrease pro-vaccination attitudes by exploiting the emotion of anger [53] (an emotion detected here) rather than through fear (which was not detected here). Anger can activate and amplify reactions such as feeling frustrated or fooled by the establishment, which can then lead to behavioural changes [46]. In this way, both the conspiratorial semantic associations and emotional signals of anger in the semantic frame of “vaccine” in popular English tweets should serve as early warning signals of misinformation hampering the vaccination campaign.

Limitations

Our analysis is subject to some limitations. TFMNs can adapt their structure but not their valence/emotional labels to the text being analysed. This is because affect data comes from predetermined large populations, and it is representative of the way common language portrays concepts [26,29,44]. Because of contextual shifts, it might be that the affective connotation of specific concepts in a given discourse could be different [30]. For instance, “vaccine” by itself was rated as mostly neutral in the dataset by Warriner and colleagues [44], but it was associated with mostly positive jargon in social discourse (see Figure 2, bottom). This limitation underlines the importance of considering words as connected with each other and not in isolation. This is because TFMNs enable the reconstruction of contextual shifts in affect by considering how words were associated with each other in language. Our machine vision and face mask routines, whilst accurate, may occasionally misclassify some images, introducing small levels of noise, which can be improved with larger training sets. In terms of the importance of context, another limitation of the current study is about the picture analysis of face masks neglects potential contextual elements. Another limitation of the current approach is that the multi-language support stems mainly from automatic translation. Hopefully, in the future, more cognitive datasets will be built by considering data from native speakers. A future research direction could merge the current semantic-emotional analysis together with content credibility dynamics, as recently quantified in social discourse about immigration [54] or about the vaccine in news media [55] by Vilella and colleagues or by Pierri and colleagues [16]. This direction would be relevant for better understanding and countering outbreaks of misinformation related to global pandemics [37], which pose a concrete threat to global health. Another limitation of this study is its exploratory nature. We did not use cognitive networks to measure, infer or predict other patterns, such as contagion curves. As such, we cannot condense the performance of our measure with an accuracy score or goodness-of-fit metric. We consider the inclusion of the TFMN feature an exciting research direction, potentially enhancing other powerful AI approaches predicting contagion curves from social media topics [34,35], vaccine hesitancy from natural language processing [36,39,40] and the impact of lockdown and other health measures [42,52].

5. Conclusions

Our work provides a methodological framework for reconstructing trending perceptions in social media via language, network and picture analyses. Warning signals of conspiratorial content and a dramatic loss of trust toward the vaccination campaign were unearthed by our investigation. Our results stress the possibilities opened by innovative and quantitative analyses of semantic frames and emotional profiles for understanding how large populations of individuals perceive and discuss events as extreme as the global pandemic and ways out of it, such as vaccines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation and methodology, M.S. and F.B.; validation, M.S., M.S.V. and F.B.; formal analysis, M.S. and F.B.; investigation M.S., M.S.V. and F.B.; data curation, M.S.; visualisation, M.S.; project administration M.S.; writing, M.S., M.S.V. and F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the data being provided within the Academic Twitter Track, a programme approved by Twitter and preserving best practice-standards of ethical data provision, i.e. anonymity and confidentiality, in accordance with the best-practice of the Declaration of Helsinki (see for reference: https://developer.twitter.com/en/products/twitter-api/academic-research/application-info, accessed on 4 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

In compliance with the Twitter Academic Track, tweet IDs for study reproducibility can be found on this Open Science Foundation repository: https://osf.io/ke6yz/ (accessed on 4 May 2022).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Riccardo Di Clemente for insightful discussion. The authors acknowledge the University of Exeter for support in publishing this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

We used images as a selection criterion for identifying specific sets of tweets, e.g., tweets containing pictures with people wearing a facemask. For each set of tweets, we performed emotional profiling based on their text.

An analysis reading the text of pictures included in popular tweets (see Section 2) identified portions of language sharing the very same emotional content as the shorter text of tweets themselves. This finding indicates an overall consistency of language between the header of a tweet and the content of the picture attached to it.

With no difference detected in the text reported in pictures, we focused our attention on pictures portraying negligible, e.g., a single word, or no text at all. An analysis of the hue values identified mainly two predominant colours in these pictures, as contained in popular tweets: (i) hue values in the red region of the spectrum and (ii) hue values in the blue region.

Within this specific set of tweets with pictures, the circumplex model identified a polarisation of emotions between calmness to alarm in their texts. Emotional profiling through the Emotional Lexicon identified a lower level of anticipation in the future in the language describing specifically pictures with a predominantly blue colour. Human coding of pictures revealed that blue was the main colour for the backgrounds and foregrounds in pictures displaying people being vaccinated. Hence the observed decrease in anticipation indicates that when describing the specific event of vaccination, language becomes less projected into the future.

In order to better investigate how language and pictures are entwined, we performed a specific content analysis based on machine vision and focused on the portrayal of people and pandemic-related objects. Since the detection of syringes or vaccine vials would be problematic, we focus on objects more tightly connected to people, such as face masks.

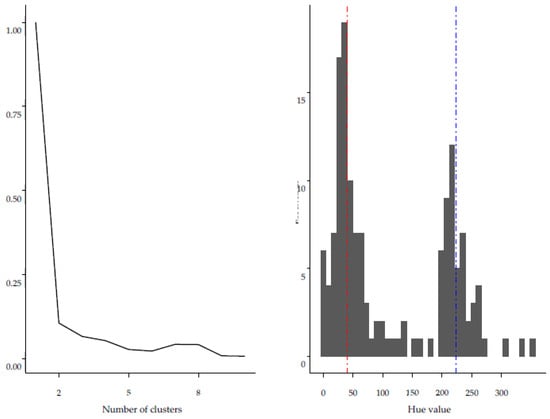

Another key component of the visual aspect of images associated the tweets is that associated with colours. Colour analysis of images posted to Instagram has revealed a link between Hue, Saturation and Value (HSV) and individuals with depression [37]. This suggests that images may, to an extent, reflect the emotional and well-being status of individuals who choose to share those images online. Here, we extract the dominant colour values in terms of the hue value. The hue value represents the colour on the light spectrum, with low values representing red and large values representing blue and purple. To extract a single hue value from each image, we perform a two-step analysis on each image that does not contain textual data. First, we run the k-means clustering algorithm on the HSV values of each pixel for each image. We then extract the centroid of the largest cluster found and consider the corresponding HSV values as the dominant values of the image. Note that this is only an approximation of the dominant colour, and we use k = 5 in each image. After this initial step, each image is represented by its dominant HSV values. Visual inspection of the resulting dominant HSV values across all images analysed indicates the presence of two strong clusters in the hue component, with one cluster centred on low values of hue (in the red spectrum) and a second cluster centred on large values of hue (in the blue spectrum). Based on this finding, we perform a second clustering step, using the k-means clustering algorithm with k = 2 to group the images into two clusters: one with dominant hue values in the red area; and one with dominant hue values in the blue area. More details about this are provided in Figure A1 and Figure A2.

Figure A1.

(Left): Elbow plot showing how the within cluster sum of squares varies as the number of clusters increase, when clustering the images based on their dominant hue values. As the plot indicates, two clusters seem to be the optimal choice. (Right): Histogram of the dominant hue values detected in the images (note: only those not containing any text were analysed in this scenario). As the visual inspection suggests, we observe two clusters centred on the red and blue tones of hue.

Figure A2.

(Top): Word cloud of the most frequent words in tweets with pictures with predominant blue or red. (Bottom): Emotional flowers and circumplex model for the emotions of the language used in tweets with pics of different predominant colours. Asterisks highlight emotions z > 1.96.

References

- Stella, M.; Ferrara, E.; De Domenico, M. Bots increase exposure to negative and inflammatory content in online social systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 12435–12440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mehler, A.; Gleim, R.; Gaitsch, R.; Hemati, W.; Uslu, T. From topic networks to distributed cog-nitive maps: Zipfian topic universes in the area of volunteered geographic information. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.01454. [Google Scholar]

- Bovet, A.; Morone, F.; Makse, H.A. Validation of Twitter opinion trends with national polling aggregates: Hillary Clinton vs. Donald Trump. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessi, A.; Ferrara, E. Social bots distort the 2016 U.S. Presidential election online discussion. First Monday 2016, 21, 7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E.; Yang, Z. Quantifying the effect of sentiment on information diffusion in social media. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2015, 1, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Bailón, S.; De Domenico, M. Bots are less central than verified accounts during contentious political events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2013443118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onur, V.; Ismail, U. Journalists on Twitter: Self-branding, audiences, and involvement of bots. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Stella, M. Cognitive Network Science for Understanding Online Social Cognitions: A Brief Review. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2021, 14, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitevitch, M. Can network science connect mind, brain, and behavior. Netw. Sci. Cogn. Psychol. 2019, 26, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, T.T. The Dark Side of Information Proliferation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, M.M.; Turney, P.D. Emotions evoked by common words and phrases: Using mechanical turk to create an emotion lexicon. In Proceedings of the NAACL HLT 2010 Workshop on Computational Approaches to Analysis and Generation of Emotion in Text, 26–34, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 10 June 2010; Association for Computational Linguistics: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore, C.J. Frame semantics. Cogn. Linguist. Basic Read 2006, 34, 373–400. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.; Kolic, B. Public risk perception and emotion on Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2020, 5, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Jiang, J.; Pal, A.; Yu, K.; Chen, F.; Yu, S. Analysis and Insights for Myths Circulating on Twitter During the COVID-19 Pandemic. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2020, 1, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M.; Restocchi, V.; De Deyne, S. #lockdown: Network-Enhanced Emotional Profiling in the Time of COVID-19. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2020, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierri, F.; Tocchetti, A.; Corti, L.; di Giovanni, M.; Pavanetto, S.; Brambilla, M.; Ceri, S. Vaccinitaly: Monitoring Italian conversations around vaccines on Twitter and Facebook. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.03757. [Google Scholar]

- Siew, C.S.Q.; Wulff, D.U.; Beckage, N.M.; Kenett, Y.N.; Meštrović, A. Cognitive Network Science: A Review of Research on Cognition through the Lens of Network Representations, Processes, and Dynamics. Complexity 2019, 2019, 2108423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M.; De Nigris, S.; Aloric, A.; Siew, C.S.Q. Forma mentis networks quantify crucial differences in STEM perception between students and experts. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiorillo, A.; Sampogna, G.; Giallonardo, V.; Del Vecchio, V.; Luciano, M.; Albert, U.; Carmassi, C.; Carrà, G.; Cirulli, F.; Dell’Osso, B.; et al. Effects of the lockdown on the mental health of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: Results from the COMET collaborative network. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, E87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, L.M.; Quercia, D.; Zhou, K.; Constantinides, M.; Šćepanović, S.; Joglekar, S. How epidemic psychology works on Twitter: Evolution of responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagiello, R.D.; Hills, T.T. Bad News Has Wings: Dread Risk Mediates Social Amplification in Risk Communication. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 2193–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimeri, K.; Beiró, M.G.; Urbinati, A.; Bonanomi, A.; Rosina, A.; Cattuto, C. Human Values and Attitudes towards Vaccination in Social Media. In Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazzuca, C.; Falcinelli, I.; Michalland, A.H.; Tummolini, L.; Borghi, A.M. Differences and similarities in the conceptualization of COVID-19 and other diseases in the first Italian lockdown. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montefinese, M.; Ambrosini, E.; Angrilli, A. Online search trends and word-related emotional response during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: A cross-sectional online study. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilek, K.; Fazli, C. Stance detection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2020, 53, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Saif, M.M. Sentiment analysis: Detecting valence, emotions, and other affectual states from text. In Emotion Measurement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 201–237. [Google Scholar]

- de Arruda, H.F.; Marinho, V.Q.; Costa, L.D.F.; Amancio, D.R. Paragraph-based representation of texts: A complex networks approach. Inf. Process. Manag. 2019, 56, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amancio, D.R. Probing the Topological Properties of Complex Networks Modeling Short Written Texts. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M. Text-mining forma mentis networks reconstruct public perception of the STEM gender gap in social media. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2020, 6, e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M.; Zaytseva, A. Forma mentis networks map how nursing and engineering students enhance their mindsets about innovation and health during professional growth. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2020, 6, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carley, K.M. Coding Choices for Textual Analysis: A Comparison of Content Analysis and Map Analysis. Sociol. Methodol. 1993, 23, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, K.M. Extracting team mental models through textual analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 1997, 18, 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdavar, A.H.; Mahdavinejad, M.S.; Bajaj, G.; Romine, W.; Monadjemi, A.; Thirunarayan, K.; Sheth, A.; Pathak, J. Fusing visual, textual and connectivity clues for studying mental health. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.06843. [Google Scholar]

- Comito, C. How COVID-19 information spread in US The Role of Twitter as Early Indicator of Epidemics. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comito, C.; Pizzuti, C. Artificial intelligence for forecasting and diagnosing COVID-19 pandemic: A focused review. Artif. Intell. Med. 2022, 128, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinert, J.I.; Sternberg, H.; Prince, H.; Fasolo, B.; Galizzi, M.M.; Büthe, T.; Veltri, G.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in eight Eu-ropean countries: Prevalence, determinants, and heterogeneity. Sci Adv. 2022, 29, eabm9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briand, S.C.; Cinelli, M.; Nguyen, T.; Lewis, R.; Prybylski, D.; Valensise, C.M.; Colizza, V.; Tozzi, A.E.; Perra, N.; Baronchelli, A.; et al. Infodemics: A new challenge for public health. Cell 2021, 184, 6010–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulhaq, A.; Born, J.; Khan, A.; Gomes, D.P.S.; Chakraborty, S.; Paul, M. COVID-19 control by computer vision approaches: A. survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 179437–179456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.L.; Peruzzi, A.; Scala, A.; Cinelli, M.; Pomerantsev, P.; Applebaum, A.; Gaston, S.; Fusi, N.; Peterson, Z.; Severgnini, G.; et al. Measuring social response to different journalistic techniques on Facebook. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, M.; Veltri, G.A. Do cognitive styles affect vaccine hesitancy? A dual-process cognitive framework for vaccine hesitancy and the role of risk perceptions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 289, 114403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, G.; Milli, L.; Citraro, S.; Morini, V. UTLDR: An agent-based framework for modeling infectious diseases and public interventions. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2021, 57, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóczi, B. An Overview of Conceptual Models and Theories of Lexical Representation in the Mental Lexicon. In The Routledge Handbook of Vocabulary Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A. WordNet: An Electronic Lexical Database; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Warriner, A.B.; Kuperman, K.; Brysbaert, M. Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 english lemmas. Behav. Res. Methods 2013, 45, 1191–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Posner, J.; Russell, J.A.; Peterson, B.S. The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2005, 17, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.E.; Davidson, R.J. The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Guo, J.; Ververas, E.; Kotsia, I.; Zafeiriou, S. Retinaface: Single-stage dense face localisation in the wild. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.00641. [Google Scholar]

- Reece, A.G.; Danforth, C.M. Instagram photos reveal predictive markers of depression. EPJ Data Sci. 2017, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blondel, V.D.; Guillaume, J.L.; Lambiotte, R.; Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008, 2018, P10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, J.; Vallières, F.; Bentall, R.P.; Shevlin, M.; McBride, O.; Hartman, T.K.; McKay, R.; Bennett, K.; Mason, L.; Gibson-Miller, J.; et al. Psychological characteristics associated with covid-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United kingdom. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radicioni, T.; Squartini, T.; Pavan, E.; Saracco, F. Networked partisanship and framing: A socio-semantic network analysis of the Italian debate on migration. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.04653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perra, N. Non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review. Phys. Rep. 2021, 913, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, J.D.; Zhang, J. Feeling angry: The effects of vaccine misinformation and refutational messages on negative emotions and vaccination attitude. J. Health Commun. 2020, 25, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilella, S.; Semeraro, A.; Paolotti, D.; Ruffo, G. The Impact of Disinformation on a Controversial Debate on Social Media. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.15968. [Google Scholar]

- Semeraro, A.; Vilella, S.; Ruffo, G.; Stella, M. Writing about COVID-19 vaccines: Emotional profiling unravels how mainstream and alternative press framed AstraZeneca, Pfizer and vaccination campaigns. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.07538. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).