Analyzing Vulnerability Through Narratives: A Prompt-Based NLP Framework for Information Extraction and Insight Generation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Domain-Specific Structuring of Vulnerability Information: Defines key information elements and their relationships within the context of gendered vulnerability, providing a structured model for socio-economic narrative analysis.

- Mapping Social Science Theoretical Constructs to NLP Techniques: Systematically maps traditional theories of narrative analysis to AI-based IE strategies.

- Adaptation of Prompt Engineering for Accessible Vulnerability Extraction: Demonstrates how prompt engineering can be adapted for extracting multidimensional vulnerability markers from real-world self-narratives, enabling usability by non-specialists.

- Human-in-the-Loop Validation Framework: The proposed analytical workflow incorporates human oversight not only at the final validation stage but also at intermediate stages, including prompt refinement, intermediate IE assessments, and quality control checks. Manual annotation and expert feedback are integrated throughout the process to ensure the correctness, interpretability, and practical applicability of the machine-extracted information.

- Graph-Based Visualization of Extracted Vulnerability Patterns: Organizes extracted information elements through unsupervised categorization and graph-based visualization, enabling structured exploration of recurring vulnerability patterns.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Aspects of Narrative Inquiry

2.2. Computational Approaches to Narrative Analysis

2.2.1. Adoption of LLMs in Social Science Studies

2.2.2. Studies in Mental Health Domain

2.3. Frameworks for Analyzing Individual Vulnerability

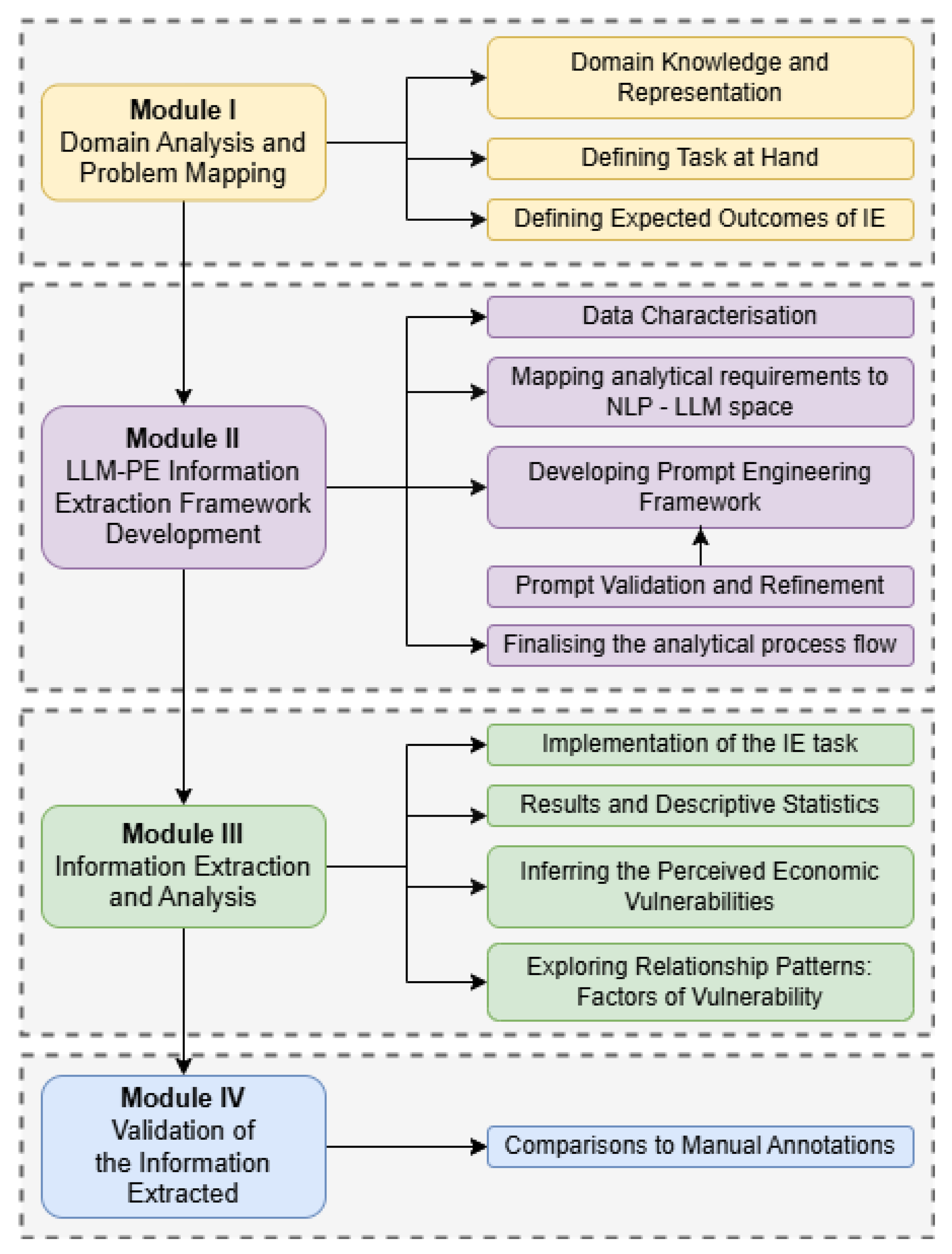

3. Methodology

3.1. Module I: Domain Analysis and Problem Mapping

3.1.1. Domain Knowledge and Representation

3.1.2. Dataset Gathered

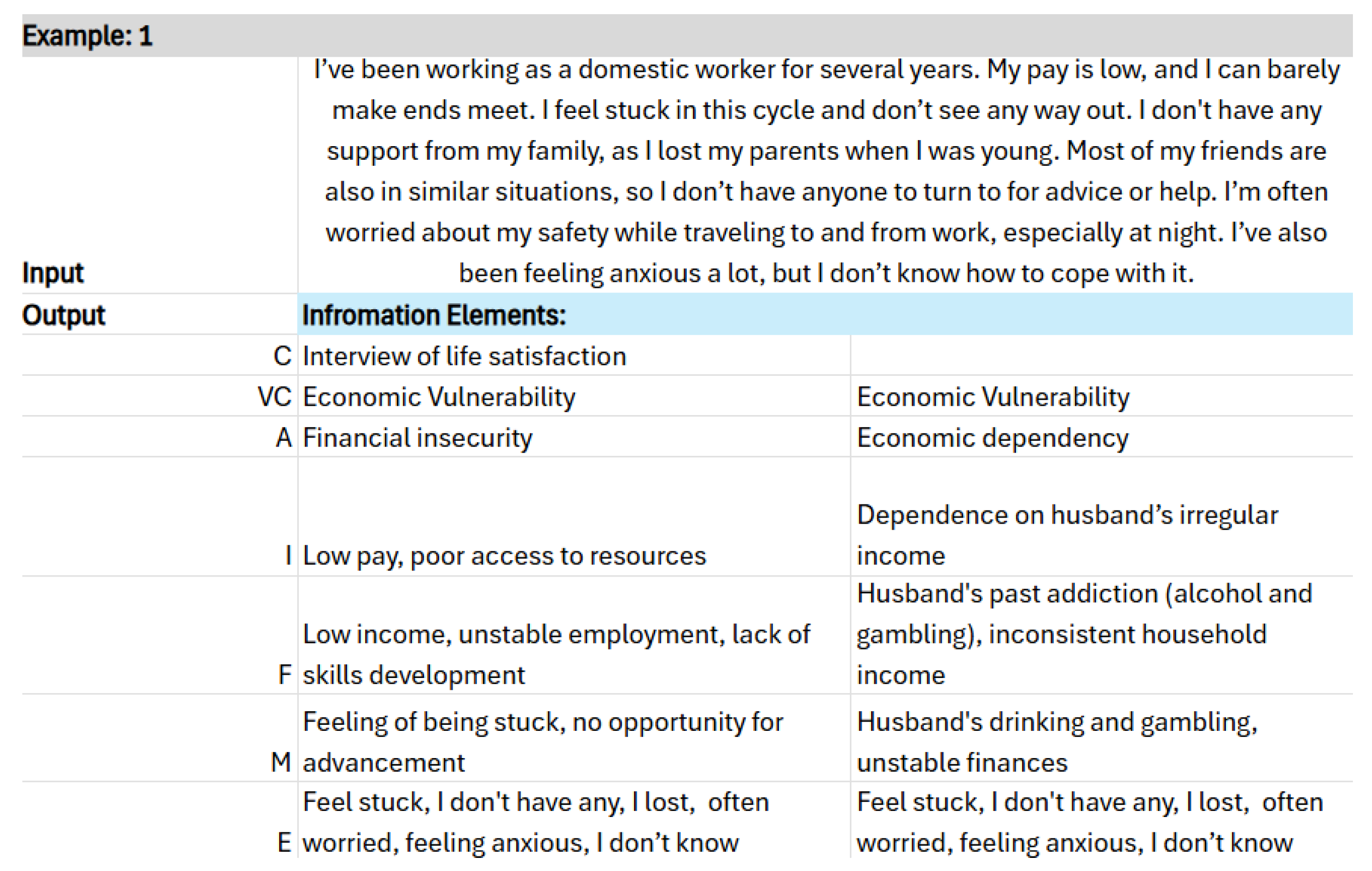

3.1.3. Annotation Guidelines and Protocol

3.2. Module II: Information Extraction (IE) Framework Development

3.2.1. Model Configuration and Context Management

- Base instructions and schema context: ∼3000–3500 tokens

- Few-shot exemplars (2–3): ∼1000–1500 tokens

- Constraints and formatting rules: ∼400–600 tokens

- Knowledge graph cues (in specific refinement iterations): ∼500–1000 tokens

- Narrative input: ∼150–350 tokens

- To maintain interpretive consistency and reduce randomness, the following model hyperparameters were applied during all runs. To maintain interpretive consistency and reduce random variation in responses, the model was operated with a temperature of 0.25 and a top-p value of 0.9, which together balanced determinism and lexical diversity. The maximum token length was set to 1500 to accommodate multi-aspect JSON outputs. The presence penalty remained at 0.0 to preserve adherence to the schema and prevent unnecessary deviations. This structured configuration was implemented to ensure that narratives were processed within a controlled, semantically coherent context, enabling reliable schema-aligned reasoning without exceeding computational limits.

3.2.2. Prompt Refinement and Context Augmentation

3.2.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Prompt Refinement Validation:

- True Positives (TP): Correctly extracted information elements that matched the reference annotations.

- False Positives (FP): Extracted elements not supported by the reference annotations.

- Novel Insights (NI): Additional relevant information not captured in the manual annotations but considered contextually valid.

- Discovery Rate (DR): The proportion of novel insights relative to all identified elements, calculated as follows:This metric provides an estimate of how effectively a prompt uncovers new, contextually meaningful insights beyond the predefined schema.

- To assess the quality and completeness of the extracted information without requiring full gold annotation of the entire corpus, we conducted a bounded evaluation using the IAA-validated subset (n = 25 narratives), which served as an expert-verified reference set. For this subset, we derived standard diagnostic indicators (precision, recall, and F1-score) to characterize extraction accuracy and completeness. These measures are reported only for the bounded subset, as the full corpus does not yet have exhaustive gold annotation.

- Information Extraction Validation:

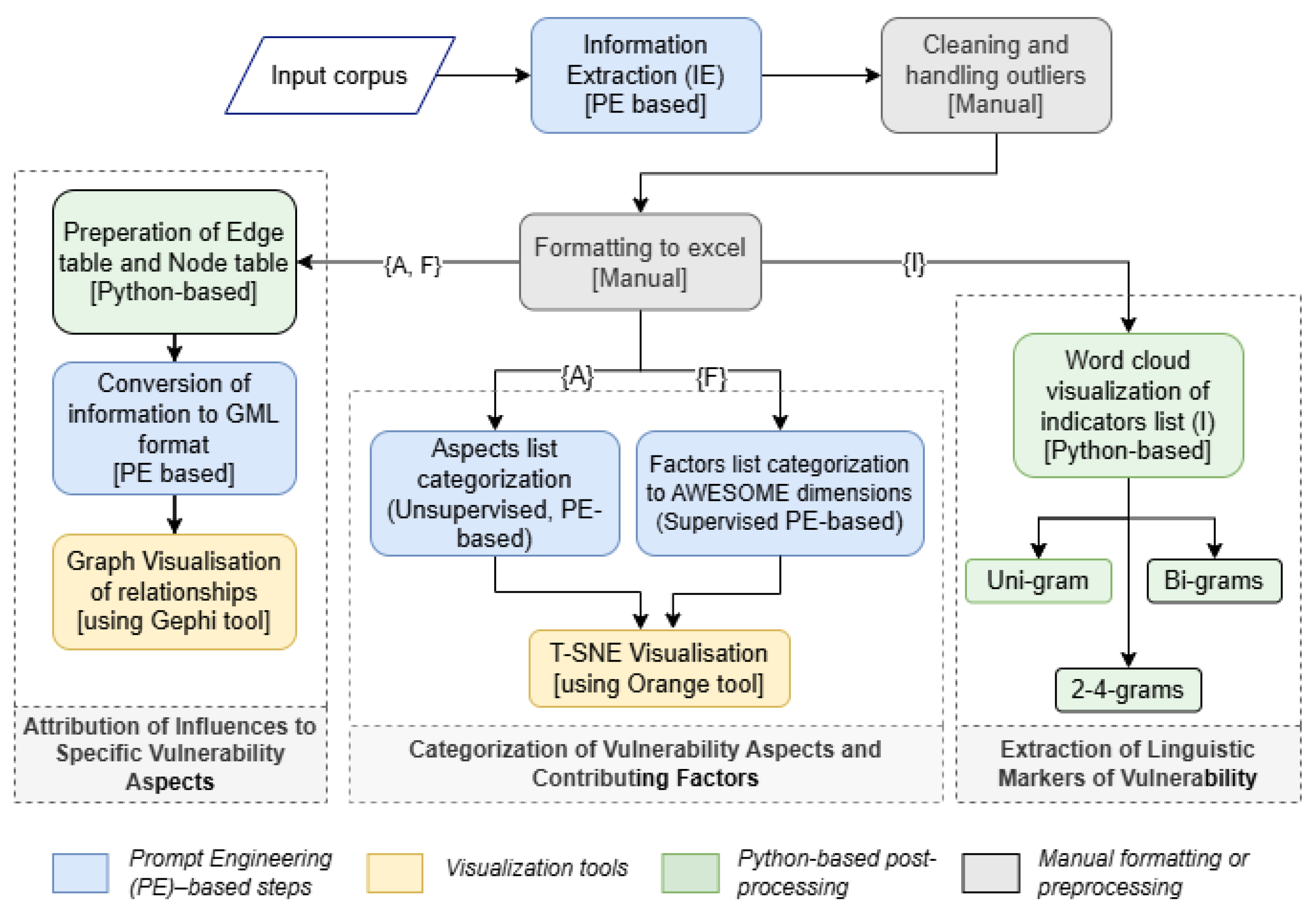

3.3. Module III: Interpretation and Insight Derivation Pipeline

3.3.1. Categorization of Vulnerability Aspects and Contributing Factors

Prompt for categorization of VA: “Given the IE results as the shared Excel sheet, from the ’aspects_list’ column, identify the semantically similar aspects and group them along with their occurrences counted as frequency.”

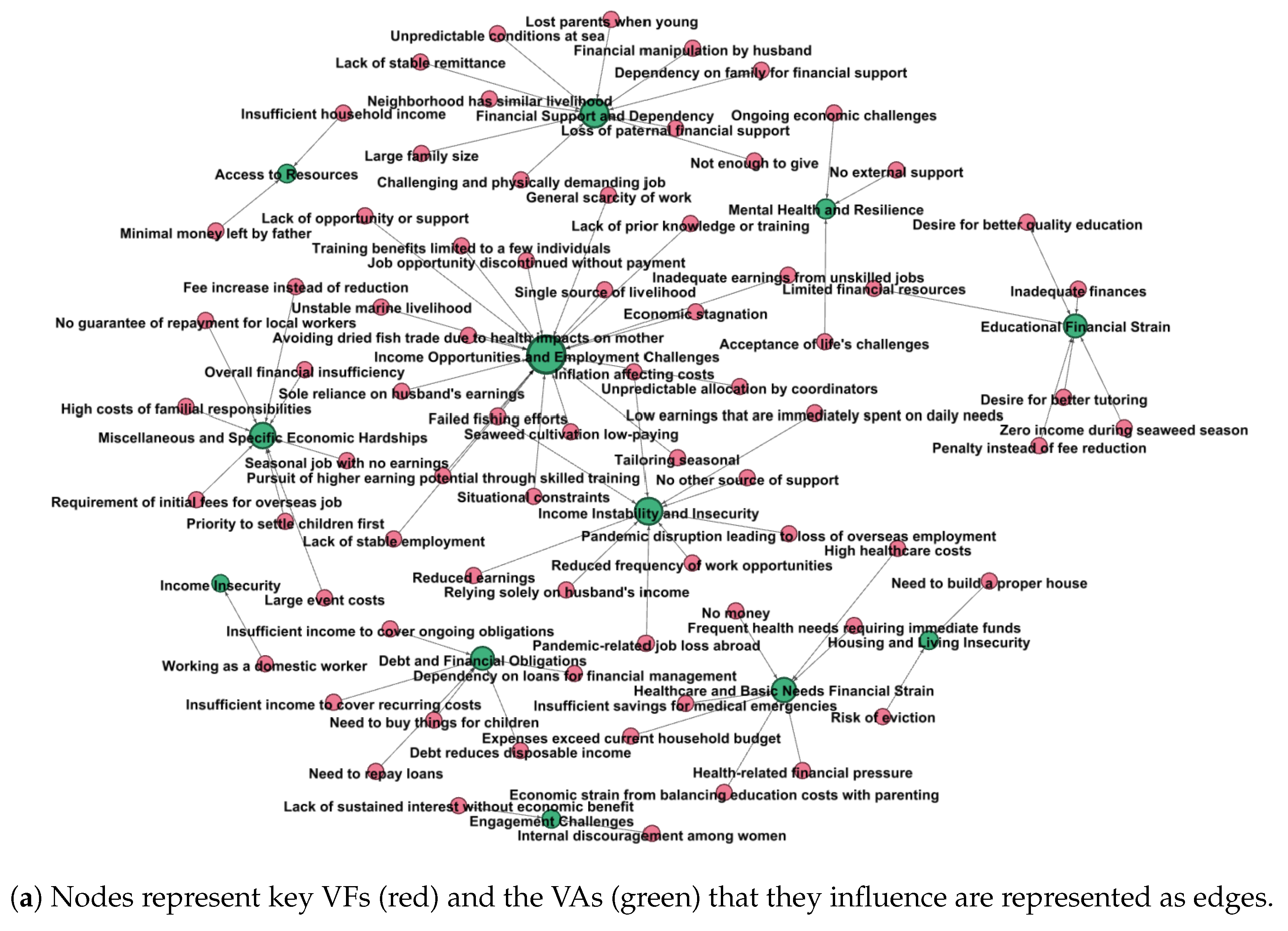

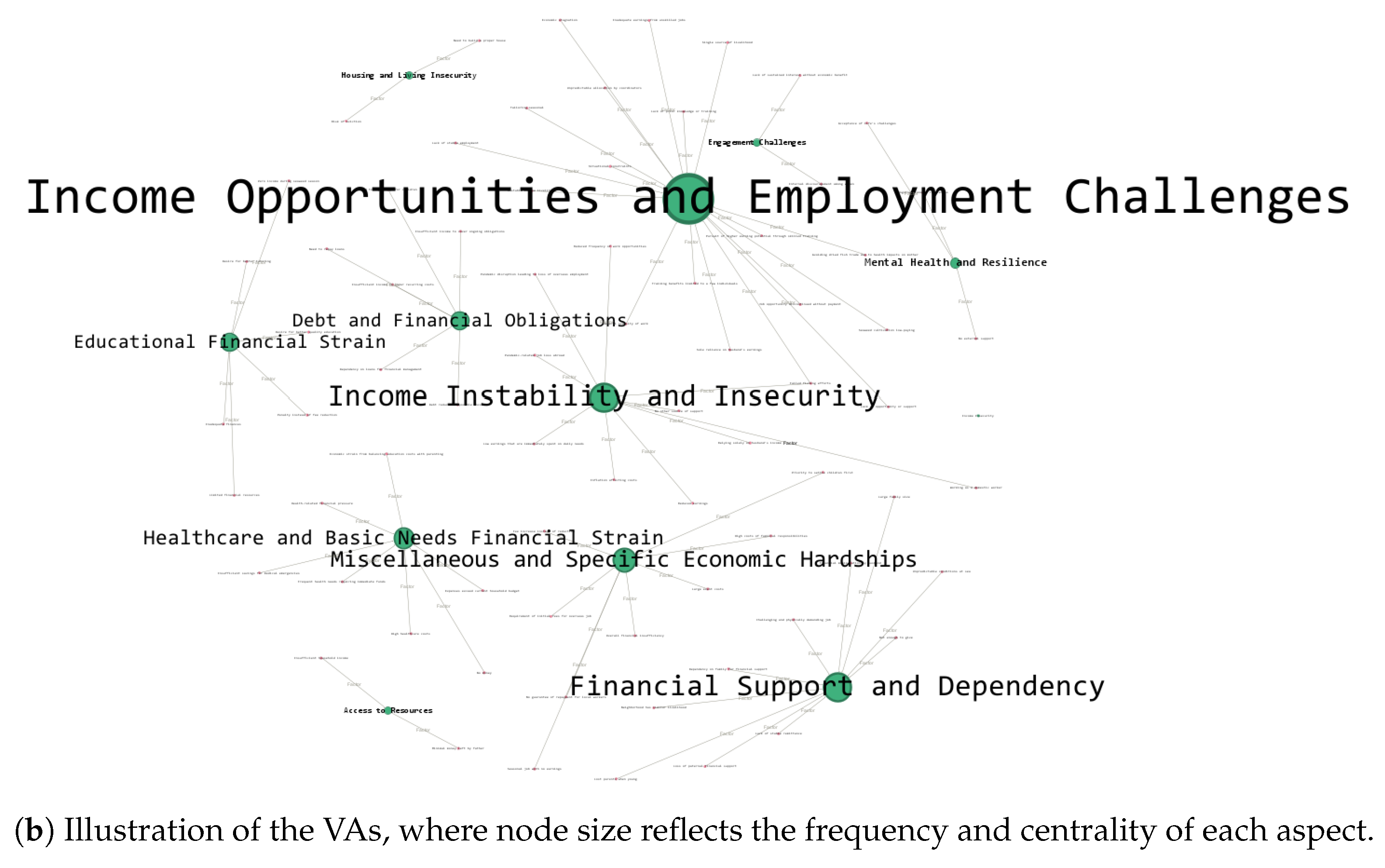

3.3.2. Attribution of Influences to Specific Vulnerability Aspects

- Preparation of Edge and Node Tables (Python-based): Structured edge and node tables were generated using Python 3.13.7 to represent relationships (edges) and entities (nodes) within the vulnerability schema. These tables formed the foundational data structure for subsequent graph construction.

- Conversion to GML Format (Prompt Engineering-Based): A prompt-engineering method was employed to transform the tabulated data into GML (Graph Modeling Language) format, enabling representation suitable for graph-based visualization and analysis.

- Graph Visualization (Gephi): The GML files were imported into Gephi to generate network visualizations of the derived relationships. This facilitated the observation and interpretation of directional influence patterns between vulnerability aspects and contributing factors.

3.3.3. Extraction of Linguistic Markers Expressing Vulnerability

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Bounded IE Quality Evaluation

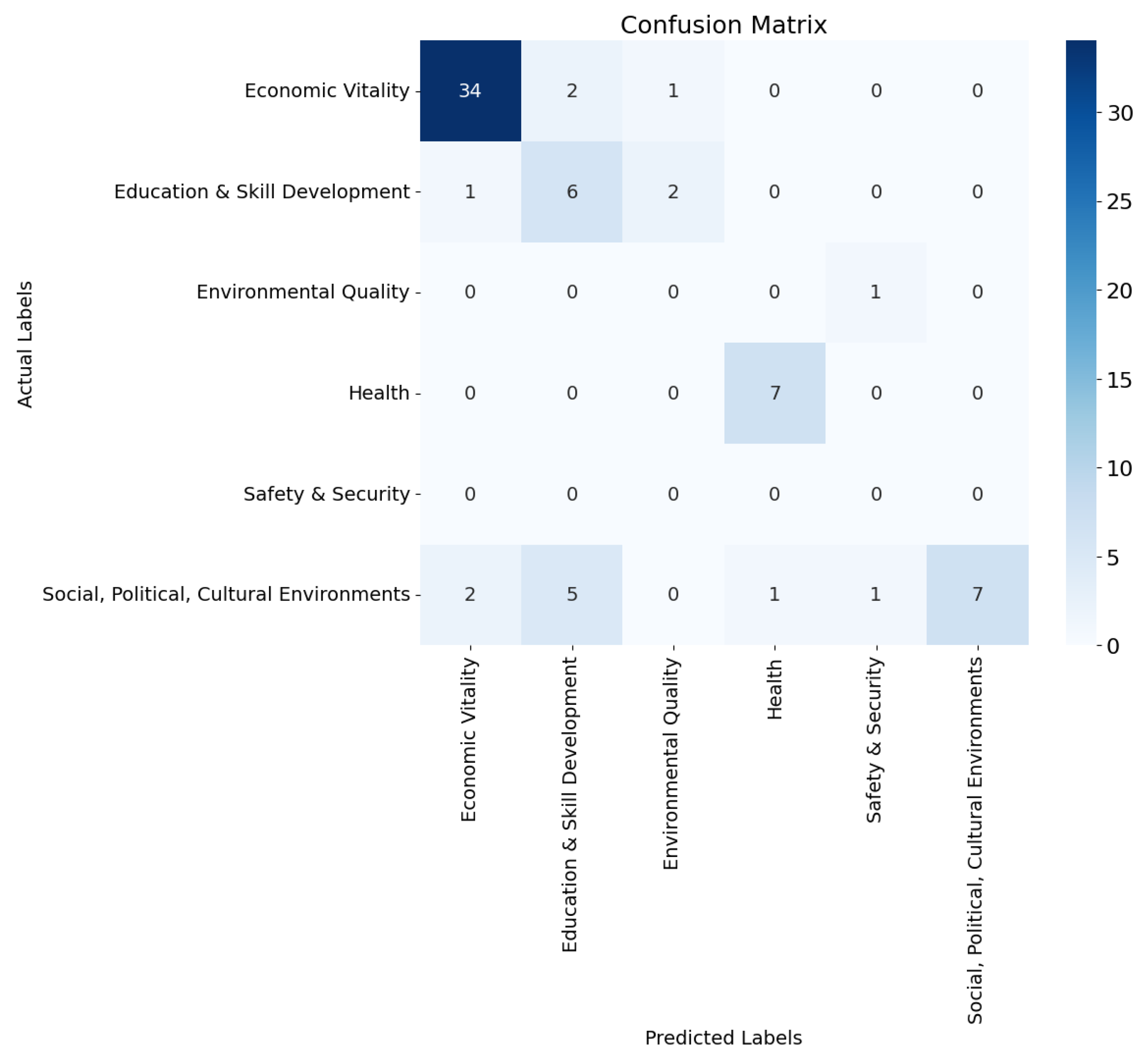

4.2. IE Models and Performance Comparison

4.3. Interpretative Results and Vulnerability Insight Discussion

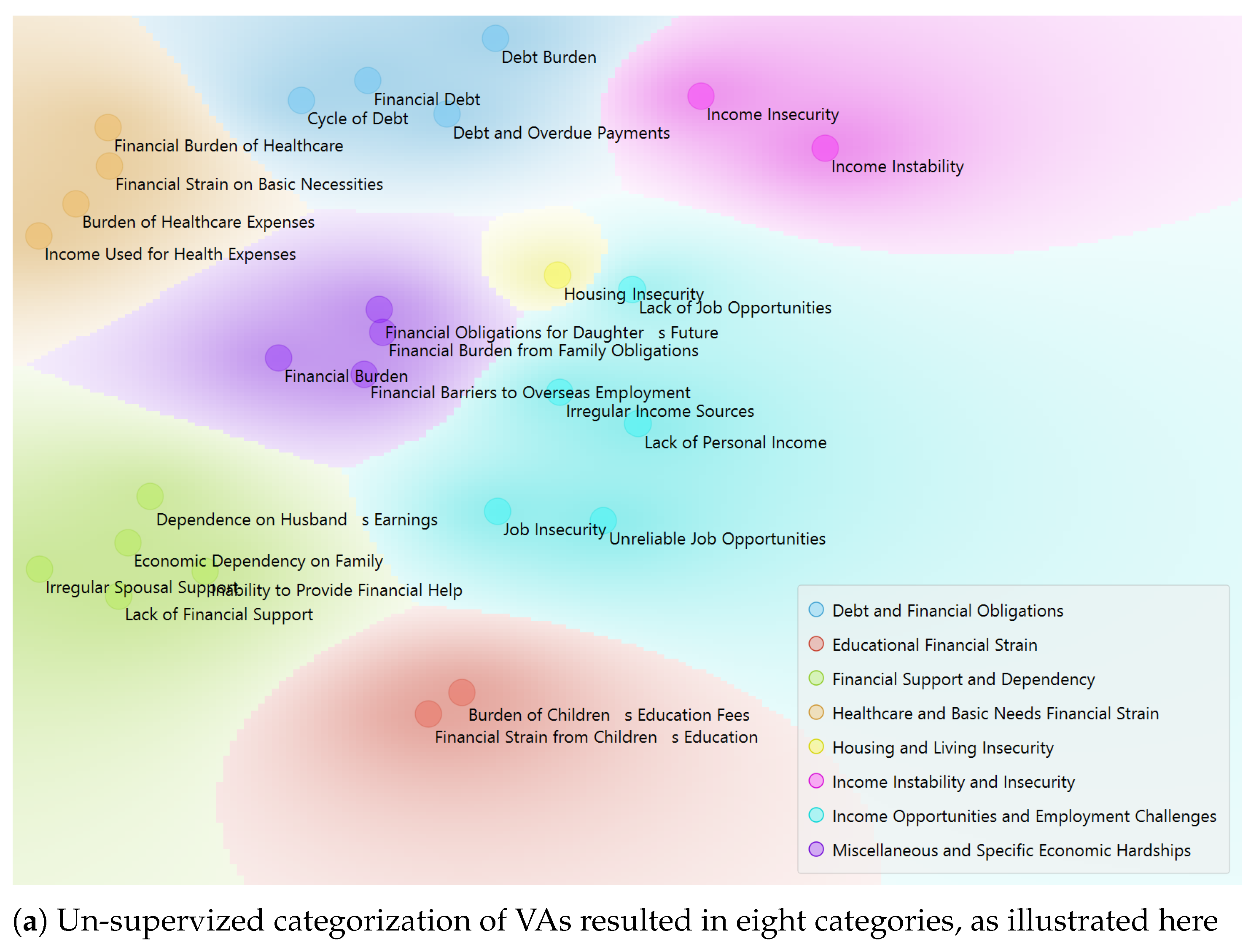

4.3.1. Identified VA and VF: Categorization Results

- VA and Categories: Unsupervised approach

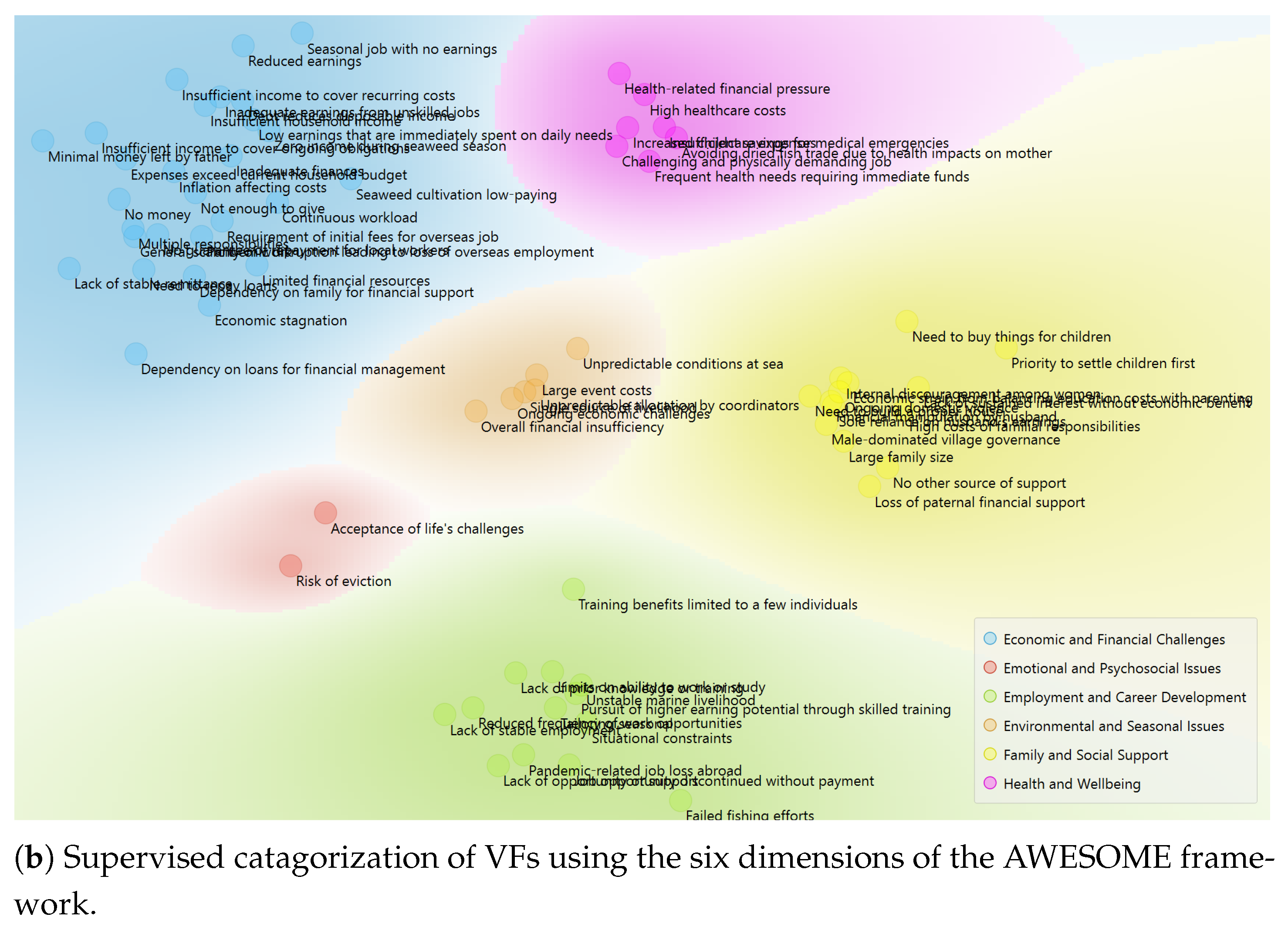

- Categories of VF: Supervised approach

4.3.2. Linguistic Markers of Economic Vulnerability

4.3.3. Perceived Influences on Vulnerability Aspects

4.4. Comparison with Manual Annotation-Based Insights

4.5. Summary of Findings

- Domain modeling using the AWESOME framework successfully structured vulnerability-related elements into four interpretable categories (Aspects, Indicators, Factors, Markers), enabling alignment between theoretical concepts and prompt design.

- Prompt engineering iterations led to improved output consistency and richness of extracted elements. Version 6 (V6), incorporating context embedding and structural cues, showed the highest consistency in reproducing multi-dimensional markers from narratives.

- Validation metrics across 70 narratives demonstrated moderate-to-high alignment with human-labeled content, with observed improvements in Discovery Rate (DR) and reduction in hallucinated outputs in later prompt versions.

- Visualization of extracted elements through t-SNE, hierarchical clustering, and knowledge graphs revealed meaningful groupings of vulnerability profiles, suggesting the framework’s potential for pattern discovery in qualitative data.

- Case-level interpretability was preserved through structured JSON outputs, maintaining contextual granularity while enabling downstream analysis.

- Overall, the pilot confirms the working hypothesis that structured prompting guided by domain theory can yield scalable, interpretable, and replicable insights from self-narratives—laying the foundation for future rigorous applications.

5. Limitations and Error Analysis

6. Conclusions and Future Works

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.; Wang, W. Knowledge domain and emerging trends of social vulnerability research: A bibliometric analysis (1991–2021). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numans, W.; Van Regenmortel, T.; Schalk, R.; Boog, J. Vulnerable persons in society: An insider’s perspective. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health-Well-Being 2021, 16, 1863598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, B. Social vulnerability as an analytical lens for welfare state research: Concepts and typologies. Policy Soc. 2017, 36, 497–515. [Google Scholar]

- Gressel, C.M.; Rashed, T.; Maciuika, L.A.; Sheshadri, S.; Coley, C.; Kongeseri, S.; Bhavani, R.R. Vulnerability mapping: A conceptual framework towards a context-based approach to women’s empowerment. World Dev. Perspect. 2020, 20, 100245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Massmann, F.; Wehrhahn, R. Qualitative social vulnerability assessments to natural hazards: Examples from coastal Thailand. J. Integr. Coast. Zone Manag. 2014, 14, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP International Center for Private Sector in Development’s (ICPSD) SDG AI Lab. Digital Social Vulnerability Index Technical Whitepaper. 2024. Available online: https://www.undp.org/publications/digital-social-vulnerability-index-technical-whitepaper (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Kim, K.; Kang, J.Y.; Hwang, C. Identifying Indicators Contributing to the Social Vulnerability Index via a Scoping Review. Land 2025, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L. The origin and diffusion of the social vulnerability index (SoVI). Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 109, 104576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenda, S.; Abercrombie, G.; Basile, V.; Pedrani, A.; Panizzon, R.; Cignarella, A.T.; Marco, C.; Bernardi, D. Perspectivist approaches to natural language processing: A survey. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2024, 59, 1719–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malgaroli, M.; Hull, T.D.; Zech, J.M.; Althoff, T. Natural language processing for mental health interventions: A systematic review and research framework. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejo-Ráez, A.; Molina-González, M.D.; Jiménez-Zafra, S.M.; García-Cumbreras, M.Á.; García-López, L.J. A survey on detecting mental disorders with natural language processing: Literature review, trends and challenges. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2024, 53, 100654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, B.; German, F.; Krokos, E.; Joseph, S.; North, C. Explainable AI Components for Narrative Map Extraction. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.16554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, F.; Keith, B.; North, C. Narrative Trails: A Method for Coherent Storyline Extraction via Maximum Capacity Path Optimization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.15681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaram, K.; Sangeeta, K. A review: Information extraction techniques from research papers. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Innovative Mechanisms for Industry Applications (ICIMIA), Chennai, India, 21–23 February 2017; pp. 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Rodriguez, J.L.; Hogan, A.; Lopez-Arevalo, I. Information extraction meets the semantic web: A survey. Semant. Web 2020, 11, 255–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Donge, W.; Bharosa, N.; Janssen, M. Data-driven government: Cross-case comparison of data stewardship in data ecosystems. Gov. Inf. Q. 2022, 39, 101642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatsal, S.; Dubey, H. A survey of prompt engineering methods in large language models for different nlp tasks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.12994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranade, P.; Dey, S.; Joshi, A.; Finin, T. Computational understanding of narratives: A survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 101575–101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, A.; So, R.J.; Bamman, D. Narrative theory for computational narrative understanding. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021; pp. 298–311. [Google Scholar]

- Nasheeda, A.; Abdullah, H.B.; Krauss, S.E.; Ahmed, N.B. Transforming transcripts into stories: A multimethod approach to narrative analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1609406919856797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolón-Dow, R.; Bailey, M.J. Insights on narrative analysis from a study of racial microaggressions and microaffirmations. Am. J. Qual. Res. 2021, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Breheny, M. Narrative analysis in health psychology: A guide for analysis. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2018, 6, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Birkbeck, G.; Nagle, T.; Sammon, D. Challenges in research data management practices: A literature analysis. J. Decis. Syst. 2022, 31, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, A. Challenges in Data Collection and Management for NGOs and How to Overcome Them. Vakilkaro. Available online: https://www.vakilkaro.com/blogs/challenges-in-data-collection-and-management-for-ngos/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Divyadarshini, S. Data-Driven Decision Making for Skilling NGOs: How MIS Can Transform Impact Measurement, EdZola. Available online: https://www.edzola.com/post/data-driven-decision-making-for-skilling-ngos-how-mis-can-transform-impact-measurement (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Santana, B.; Campos, R.; Amorim, E.; Jorge, A.; Silvano, P.; Nunes, S. A survey on narrative extraction from textual data. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 8393–8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedungadi, P.; Lathabai, H.H.; Raman, R. Large Language Models in Biomedicine and Health: A Holistic Evaluation of the Effectiveness, Reliability and Ethics using Altmetrics. J. Scientometr. Res. 2025, 14, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirova, A.; Fteropoulli, T.; Ahmed, N.; Cowie, M.R.; Leibo, J.Z. Framework-based qualitative analysis of free responses of Large Language Models: Algorithmic fidelity. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wu, S.; Diao, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Gao, J. Sayself: Teaching llms to express confidence with self-reflective rationales. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 5985–5999. [Google Scholar]

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M.S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.07258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.J.; Jensen, E.; Munro, M.H.; Zamponi, V.; Martinez, J.; O’Brien, K.; Feldhaus, B.; Smith, K.; Reinhold, A.M.; Gore, R. GPT-4 Generated Narratives of Life Events using a Structured Narrative Prompt: A Validation Study. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.05435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matus, M.; Urrutia, D.; Meneses, C.; Keith, B. ROGER: Extracting Narratives Using Large Language Models from Robert Gerstmann’s Historical Photo Archive of the Sacambaya Expedition in 1928. In Proceedings of the Text2Story@ ECIR, Glasgow, Scotland, 24 March 2024; pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, L.S.; Prabha, R.; Ramesh, M.V. Developing information extraction system for disaster impact factor retrieval from Web News Data. In Information and Communication Technology for Competitive Strategies (ICTCS 2021) Intelligent Strategies for ICT; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Elfes, J. Mapping News Narratives Using LLMs and Narrative-Structured Text Embeddings. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2409.06540. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.T.; Hsu, Y.C.; Lin, X.; Shi, X.Q.; Niu, Y.; Hsu, H.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Hsu, W. Unveiling Narrative Reasoning Limits of Large Language Models with Trope in Movie Synopses. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 14839–14854. [Google Scholar]

- Ziems, C.; Held, W.; Shaikh, O.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, D. Can large language models transform computational social science? Comput. Linguist. 2024, 50, 237–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bail, C.A. Can Generative AI improve social science? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2314021121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Schmälzle, R. Artificial intelligence for health message generation: An empirical study using a large language model (LLM) and prompt engineering. Front. Commun. 2023, 8, 1129082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yin, Z.; Tyson, G.; Haq, E.U.; Lee, L.H.; Hui, P. Apt-pipe: A prompt-tuning tool for social data annotation using chatgpt. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, Singapore, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Lin, K.; Azarnasab, E.; Ahmed, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Zeng, M.; Wang, L. Mm-react: Prompting chatgpt for multimodal reasoning and action. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.11381. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, C.; Zhao, X.; Lu, J.; Deng, C.; Zheng, C.; Wang, J.; Chowdhury, T.; Li, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Domain Specialization as the Key to Make Large Language Models Disruptive: A Comprehensive Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2305.18703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveen, J.R.; Ganesh, H.B.; Kumar, M.A.; Soman, K.P. Distributed Representation of Healthcare Text Through Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis. In Computer Aided Intervention and Diagnostics in Clinical and Medical Images; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Bartal, A.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Chan, S.J.; Babu, M.S.; Dekel, S. Identifying women with postdelivery posttraumatic stress disorder using natural language processing of personal childbirth narratives. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, N.; Reichart, R.; Dror, R. The Alternative Annotator Test for LLM-as-a-Judge: How to Statistically Justify Replacing Human Annotators with LLMs. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.10970. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Jiang, B.; Huang, L.; Beigi, A.; Zhao, C.; Tan, Z.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, C.; Wu, T.; et al. From generation to judgment: Opportunities and challenges of llm-as-a-judge. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.16594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lyu, C.; Ji, T.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, D.; Shi, S.; Tu, Z. Document-Level Machine Translation with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, ACL Anthology, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 16646–16661. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, M. Optimizing Machine Translation through Prompt Engineering: An Investigation into ChatGPT’s Customizability. In Proceedings of the Machine Translation Summit XIX, Vol. 2: Users Track, Macau, China, 4–8 September 2023; Asia-Pacific Association for Machine Translation. pp. 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Muktadir, G.M. A brief history of prompt: Leveraging language models. (through advanced prompting). arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.04438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhao, K.; Loney, J.; Li, Z.; Visentin, A. Zero-Shot Image-Based Large Language Model Approach to Road Pavement Monitoring. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.06785. [Google Scholar]

| Concept | Description | Notation |

|---|---|---|

| Women’s Empowerment | The process of increasing women’s choices and capacity to make discerning decisions towards sustainability and resilience (adopted from AWESOME framework [4]). | WE |

| Women’s Vulnerability | A state of women’s empowerment at a given point in time, determined as the net product of interactions between multiple factors, constraints, and intervention impacts shaping women’s choices and capacity to make discerning decisions across all the domains and contexts of women’s empowerment (Adopted from AWESOME framework [4]) | WV |

| Vulnerability Category | A broad grouping of vulnerabilities under a particular dimension (e.g., Economic Vulnerabilities) that is being considered at any given point in time of the qualitative analysis. | VC |

| Vulnerability Aspects | Thematic subdivisions or focus areas within a VC that capture specific types of vulnerability experiences (e.g., job insecurity, income instability, financial dependence). Or, in other words, an individual’s vulnerabilities manifest through these aspects. | VA |

| Vulnerability Indicator | A measurable sign or metric used to assess and identify the level of vulnerability an individual or group may experience. It provides direct evidence of vulnerability, making them important for identifying current or potential problems in a more factual way. | VI |

| Vulnerability Factor | The conditions or circumstances that influence an individual’s or group’s risk of harm, disadvantage, or reduced well-being. | VF |

| Vulnerability marker | Markers are specific phrases or words that give insight into the underlying emotional or psychological states, helping to better understand how vulnerability is experienced on a personal level. Often, it is less direct. | VM |

| Vulnerability Expressions | Linguistic expressions of vulnerability are how people use language to express their vulnerable emotions or states. | VE |

| Metric | Mean (μ) | Std. Dev. (σ) |

|---|---|---|

| True Positives (TP) | 88.6 | 2.70 |

| False Positives (FP) | 26.6 | 2.41 |

| False Negatives (FN) | 34.2 | 4.66 |

| Precision | 0.769 | 0.021 |

| Recall | 0.722 | 0.033 |

| F1 Score | 0.745 | 0.028 |

| Prompt Revision | TP | NI | FP | DR | Pr.order | PE Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-Basic | NA [Descriptive response] | 7 | Basic | |||

| P-Out | 152 | 92 | 118 | 35.87% | 5 | o/p structure |

| P-Out-FS | 198 | 50 | 101 | 19.9% | 6 | o/p schema, Few-shot |

| P-Out-CNST-FS | 248 | 75 | 67 | 23.9% | 2 | o/p structure, Constrained, Few-shot |

| P-COT-FS | 207 | 76 | 109 | 27.1% | 3 | o/p schema, Chain-of-thought, Few-shot |

| P-AUG-FS-CNST | 265 | 76 | 58 | 22.7% | 1 | o/p schema, Semantic n/w, Few-shot, Constrained |

| P-AUG-FS-CNST-COT | 209 | 76 | 101 | 24.8% | 4 | o/p schema, Semantic n/w, Few-shot, Constrained, Chain-of-thought |

| Grand Total/Avg. | 1279 | 445 | 554 | 25.70 | ||

| Dimension | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Vitality | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 37 |

| Education and Skill Development | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 9 |

| Environmental Quality | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1 |

| Health | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 7 |

| Safety and Security | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 |

| Social, Political, Cultural Environments | 1.00 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 16 |

| Accuracy | 0.77 (70 samples) | |||

| Macro Average | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 70 |

| Weighted Average | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 70 |

| Category | Limitation and Example | Implication/Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Annotation | IAA computed for a subset of 25 narratives extracts only. Single-annotator protocol used for rest of the dataset. | Risk of subjectivity. Mitigated by expert review of annotations; multi-annotator protocol for a larger dataset with multi-lingual data sources is currently in progress. |

| Model | Errors in interpreting relational structures (e.g., misreading line diagrams in augmented prompts) | Misclassification of relationships while using multimodal context augmentation. Could be improved by refining visual encoding in context augmentation or using different relation representations. |

| Data | Under-representation of categories such as Environmental Quality and Safety and Security | This was not a case of lower performance but rather a natural occurrence from narratives. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Padmavilochanan, A.; Gangadharan, V.; Rashed, T.; Natarajan, A. Analyzing Vulnerability Through Narratives: A Prompt-Based NLP Framework for Information Extraction and Insight Generation. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2026, 10, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010006

Padmavilochanan A, Gangadharan V, Rashed T, Natarajan A. Analyzing Vulnerability Through Narratives: A Prompt-Based NLP Framework for Information Extraction and Insight Generation. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2026; 10(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010006

Chicago/Turabian StylePadmavilochanan, Aswathi, Veena Gangadharan, Tarek Rashed, and Amritha Natarajan. 2026. "Analyzing Vulnerability Through Narratives: A Prompt-Based NLP Framework for Information Extraction and Insight Generation" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 10, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010006

APA StylePadmavilochanan, A., Gangadharan, V., Rashed, T., & Natarajan, A. (2026). Analyzing Vulnerability Through Narratives: A Prompt-Based NLP Framework for Information Extraction and Insight Generation. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 10(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010006