Development of an Ozone (O3) Predictive Emissions Model Using the XGBoost Machine Learning Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Dataset

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Preprocessing Phase

2.3.2. Dataset Phase

- Experiment 1. The first method assesses the model’s ability to extrapolate to unseen regimes. The dataset was divided into seasonal segments: records for autumn, winter, and spring were used for the training set (approximately 75% of the data), while summer records were reserved exclusively for the testing set.

- Experiment 2. To evaluate robustness across all climatic conditions, the second method applies a chronological stratified sampling strategy. For each season, the first 80% of consecutive records are assigned to training, with the remaining 20% set aside for testing. This approach ensures that temporal continuity is preserved while capturing the dynamics of all seasons in both stages.

2.3.3. Training Phase

2.3.4. Testing Phase

- Self-Prediction: Evaluating the performance of the predictive model using test data from the source monitoring station.

- Spatial Generalization: Applying the predictive model to test datasets from the other five monitoring stations to assess transferability.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1

Model Interpretability and Physical Drivers

- The AQMS-NL06 model identified historical ozone statistics as the main features. The 6-h rolling mean (O3_mean_6h) and maximum (O3_max_6h) are the most important, followed closely by the autoregressive lags. This indicates a highly stable atmospheric regime where short-term persistence is a reliable predictor across seasons.

- In sharp contrast to the industrial station (AQMS-NL03), where precursor gases played a visible role, in AQMS-NL06, the chemical variables (NOx, ) rank below the top 12. This confirms that Santa Catarina (AQMS-NL06) behaves as a stable urban background site, where ozone accumulation is driven by regional transport and atmospheric stability rather than immediate local emission spikes (titration).

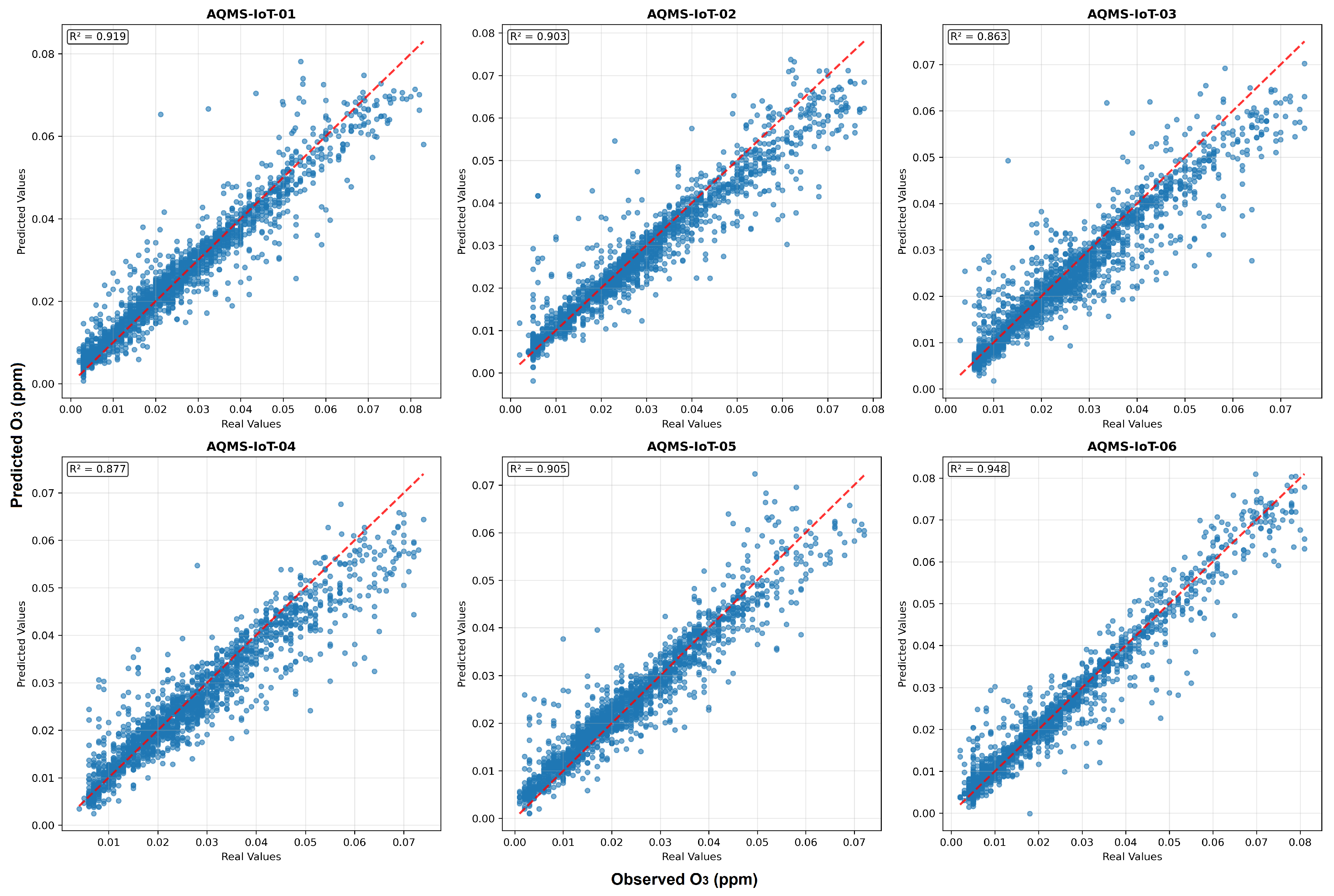

3.2. Experiment 2

3.3. Residual Diagnostics and Calibration Analysis

- The mean residual is approximately zero (−0.0014 ppm), indicating that the model predictions are centered on the observed values without systematic over- or under-estimation bias (the zero-line runs through the middle of the distribution).

- For most of the operational range (0.01 to 0.05 ppm), the residuals show a consistent dispersion density, appearing as a uniform band rather than a diverging funnel. This indicates that the model maintains stable precision across typical ozone concentrations.

- When predicted values exceed 0.06 ppm, an increase in residual variance is observed, with scattered points reaching beyond the ppm range. This pattern is consistent with the stochastic nature of extreme pollution events. Nevertheless, the vast majority of residuals remain bounded within the interval (standard deviation = 0.0039 ppm), confirming that the model’s error distribution is statistically stable for operational forecasting.

4. Discussion

4.1. Robustness and Error Diagnostics

4.2. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.3. Benchmarking with Global Ozone Forecasting Studies

4.4. Physical Interpretation and Operational Applicability

- Highly applicable in urban backgrounds and commercial zones, acting as a reliable “virtual sensor” for gap-filling and public health alerts.

- Limited in industrial corridors (e.g., AQMS-NL03), where pollutant behavior is dominated by stochastic, high-intensity point-source emissions (e.g., sudden NOx plumes causing titration). Since these events are neither strictly periodic nor purely inertial, the model, without real-time precursor data, reaches its validity limit. Therefore, for industrial applications, we recommend combining this inertial model with real-time emissions monitoring to more effectively detect nonstationary spikes.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| O3 | Ozone |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NO2 | Nitrogen Dioxide |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| CH4 | Methane |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| O2 | Molecular Oxygen |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| RFE | Recursive Feature Elimination |

| BO | Bayesian Optimization |

| AQMS | Air Quality Monitoring Station |

| T | Temperature |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| BP | Barometric Pressure |

| WS | Wind Speed |

| WD | Wind Direction |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MSE | Mean squared error |

Appendix A

| Station ID | O3 | NO | NO2 | NOx | TMP | RH | BP | WS | WD | Total Imputed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL01 | 4.52 | 2.59 | 2.72 | 2.68 | 1.42 | 1.74 | 1.46 | 1.43 | 1.46 | 2.22 |

| NL02 | 4.57 | 3.58 | 3.60 | 3.62 | 1.29 | 2.04 | 1.39 | 1.31 | 1.44 | 2.54 |

| NL03 | 3.61 | 4.28 | 3.48 | 4.45 | 2.09 | 1.42 | 1.21 | 1.68 | 1.91 | 2.68 |

| NL04 | 4.98 | 3.88 | 3.88 | 3.89 | 1.59 | 1.96 | 1.67 | 1.27 | 2.16 | 2.81 |

| NL05 | 4.75 | 4.61 | 4.71 | 4.60 | 1.16 | 1.31 | 1.45 | 1.16 | 1.22 | 2.78 |

| NL06 | 4.38 | 4.42 | 3.96 | 4.43 | 1.45 | 1.60 | 2.03 | 1.52 | 1.51 | 2.81 |

| Average | 4.47 | 3.89 | 3.73 | 3.95 | 1.50 | 1.68 | 1.54 | 1.40 | 1.62 | 2.64 |

| Variable | Unit | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Ozone | ppm | |

| Nitric Oxide | ppm | NO |

| Nitrogen Dioxide | ppm | |

| Nitrogen Oxides | ppm | NOx |

| Temperature | °C | T |

| Relative humidity | % | RH |

| Barometric pressure | mmHg | BP |

| Wind speed | m/s | WS |

| Wind direction | °A | WD |

References

- Zhang, J.J.; Wei, Y.; Fang, Z. Ozone Pollution: A Major Health Hazard Worldwide. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, G.; Siciliano, B.; da Silva, C.M.; Arbilla, G. A reactivity analysis of volatile organic compounds in a Rio de Janeiro urban area impacted by vehicular and industrial emissions. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Tan, X.; Fang, C. Analysis of NOx Pollution Characteristics in the Atmospheric Environment in Changchun City. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Rondón, A.; Ducati, J.; Haag, R. Satellite-based estimation of NO2 concentrations using a machine-learning model: A case study on Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Atmósfera 2022, 37, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa Echeverría, R.; Alarcón Jiménez, A.L.; del Carmen Torres Barrera, M.; Sánchez Alvarez, P.; Granados Hernandez, E.; Vega, E.; Jaimes Palomera, M.; Retama, A.; Gay, D.A. Nitrogen and sulfur compounds in ambient air and in wet atmospheric deposition at Mexico city metropolitan area. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 292, 119411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, S.; Barbuta-Misu, N.; Paraschiv, S.L. Influence of NO2, NO and meteorological conditions on the tropospheric O3 concentration at an industrial station. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zheng, B.; Li, K.; Liu, Y.; Lin, J.; Fu, T.M.; Zhang, Q. Exploring 2016–2017 surface ozone pollution over China: Source contributions and meteorological influences. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 8339–8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, H. Correlation between surface PM2.5 and O3 in eastern China during 2015–2019: Spatiotemporal variations and meteorological impacts. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 294, 119520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Lin, C.; Vu, C.T.; Cheruiyot, N.K.; Nguyen, M.K.; Le, T.H.; Lukkhasorn, W.; Vo, T.D.H.; Bui, X.T. Tropospheric ozone and NOx: A review of worldwide variation and meteorological influences. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 13–17 August 2016; KDD ’16, pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazkar, M.; Menapace, A.; Brentan, B.; Piraei, R.; Jimenez, D.; Dhawan, P.; Righetti, M. Applications of XGBoost in water resources engineering: A systematic literature review (Dec 2018–May 2023). Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 174, 105971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, W. A Comparative Performance Assessment of Ensemble Learning for Credit Scoring. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Sun, Y. A Survey of Ensemble Learning: Concepts, Algorithms, Applications, and Prospects. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 99129–99149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; An, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Yu, H.; Zhou, X.; Geng, Y.A. Application of XGBoost algorithm in the optimization of pollutant concentration. Atmos. Res. 2022, 276, 106238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, R.V.; Andenna, C. Exploring the Influencing Factors of Surface Ozone Variability by Explainable Machine Learning: A Case Study in the Basilicata Region (Southern Italy). Atmosphere 2025, 16, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Bi, J. Spatiotemporal distributions of surface ozone levels in China from 2005 to 2017: A machine learning approach. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, Q.; Li, M.; Xie, M.; Li, S.; Zhuang, B.; Kalsoom, U. Unveiling Spatiotemporal Differences and Responsive Mechanisms of Seamless Hourly Ozone in China Using Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Yuan, J.; Cao, Z.; Cao, T.; Liu, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X. Comparison of machine learning methods for predicting ground-level ozone pollution in Beijing. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1561794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Huang, G.; Wang, J.; Zeng, H. VAR-tree model based spatio-temporal characterization and prediction of O3 concentration in China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 257, 114960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Xue, W.; Zhou, L.; Che, Y.; Han, T. Estimation of the Near-Surface Ozone Concentration with Full Spatiotemporal Coverage across the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region Based on Extreme Gradient Boosting Combined with a WRF-Chem Model. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X. Feature selection for global tropospheric ozone prediction based on the BO-XGBoost-RFE algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; He, J.; Lei, R.; Fan, M.; Huang, H. Accurate and efficient prediction of atmospheric PM1, PM2.5, PM10, and O3 concentrations using a customized software package based on a machine-learning algorithm. Chemosphere 2024, 368, 143752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez, E.K.; Petersen, M.R. A Comparison of Machine Learning Methods to Forecast Tropospheric Ozone Levels in Delhi. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Cui, L.; Hongbo, F.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J. Satellite-based estimation of full-coverage ozone (O3) concentration and health effect assessment across Hainan Island. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Lu, P.; Chen, Z.; Liu, R. Ozone Concentration Estimation and Meteorological Impact Quantification in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region Based on Machine Learning Models. Earth Space Sci. 2024, 11, 003346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de México. Metrópolis de México 2020, 2024. Secretaría de Desarrollo Agrario, Territorial y Urbano. Ciudad de México. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/sedatu/MM2020_06022024.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- INEGI. Aspectos Geográficos de Nuevo León; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, México, 2023; Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/areasgeograficas/resumen/resumen_19.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, México, 2020; Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/#datos_abiertos (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Mancilla, Y.; Paniagua, I.H.; Mendoza, A. Spatial differences in ambient coarse and fine particles in the Monterrey metropolitan area, Mexico: Implications for source contribution. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2019, 69, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economy. Nuevo León: Economy, Employment, Equity, Quality of Life, Education, Health, and Public Safety; Ministry of Economy: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/nuevo-leon-nl (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- INEGI. Vehículos de Motor Registrados en Circulación (VMRC); Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, México, 2023; Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/vehiculosmotor/#datos_abierto (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- SEMARNAT. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-156-SEMARNAT-2012, Establecimiento y Operación de Sistemas de Monitoreo de la Calidad del Aire, 2016. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/profepa/documentos/norma-oficial-mexicana-nom-156-semarnat-2012 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- SSA Salud ambiental. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-020-SSA1-2021, Criterio Para Evaluar la Calidad del Aire Ambiente, con Respecto al Ozono O3. 2021. Secretaría de Salud. Available online: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5633956&fecha=28/10/2021#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Chang, W.; Chen, X.; He, Z.; Zhou, S. A Prediction Hybrid Framework for Air Quality Integrated with W-BiLSTM(PSO)-GRU and XGBoost Methods. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Zhao, C.; Hu, Y.; Tian, Y. Predicting the Concentration Levels of PM2.5 and O3 for Highly Urbanized Areas Based on Machine Learning Models. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.V.; Kling, H.; Yilmaz, K.K.; Martinez, G.F. Decomposition of the mean squared error and NSE performance criteria: Implications for improving hydrological modelling. J. Hydrol. 2009, 377, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station ID | Location (City) | Coordinates (Lat, Lon) |

|---|---|---|

| AQMS-NL01 | Guadalupe | 25.6643, −100.2450 |

| AQMS-NL02 | San Nicolás | 25.7450, −100.2530 |

| AQMS-NL03 | Apodaca | 25.7773, −100.1882 |

| AQMS-NL04 | Juárez | 25.6460, −100.0957 |

| AQMS-NL05 | Cadereyta | 25.6008, −99.9958 |

| AQMS-NL06 | Santa Catarina | 25.6756, −100.4654 |

| Quantity | Type | Variable |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | Air pollution | (target), NOx, NO, |

| 4 | Meteorological | T, RH, BP, WS |

| 8 | Cyclic time | hour_sin, hour_cos, day_sin, day_cos, dow_sin, dow_cos, month_sin, month_cos |

| 2 | Cyclic wind | WD_sin, WD_cos |

| 1 | Weekend indicator | is_weekend (binary) |

| 12 | Rolling window | mean_6h, mean_12h, mean_24h, sd_6h, sd_12h, sd_24h, min_6h, min_12h, min_24h, max_6h, max_12h, max_24h |

| 7 | Lagged variable | O3_lag_1h, O3_lag_2h, O3_lag_3h, O3_lag_4h, O3_lag_5h, O3_lag_6h, O3_lag_7h |

| Stations | R2 | MSE (ppm2) | RMSE (ppm) | MAE (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.93 | 0.000017 | 0.0041 | 0.0029 |

| AQMS-NL02 | 0.93 | 0.000015 | 0.0039 | 0.0027 |

| AQMS-NL03 | 0.83 | 0.000042 | 0.0065 | 0.0044 |

| AQMS-NL04 | 0.91 | 0.000016 | 0.0039 | 0.0030 |

| AQMS-NL05 | 0.90 | 0.000017 | 0.0042 | 0.0027 |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.96 | 0.000011 | 0.0034 | 0.0023 |

| Station Model | Station Test Dataset | R2 | MSE (ppm2) | RMSE (ppm) | MAE (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.94 | 0.000016 | 0.0040 | 0.0028 | |

| AQMS-NL03 | 0.89 | 0.000028 | 0.0053 | 0.0035 | |

| AQMS-NL02 | AQMS-NL04 | 0.93 | 0.000013 | 0.0037 | 0.0027 |

| AQMS-NL05 | 0.89 | 0.000019 | 0.0044 | 0.0030 | |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.95 | 0.000012 | 0.0035 | 0.0025 | |

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.91 | 0.000023 | 0.0048 | 0.0030 | |

| AQMS-NL02 | 0.88 | 0.000026 | 0.0051 | 0.0034 | |

| AQMS-NL05 | AQMS-NL03 | 0.81 | 0.000046 | 0.0068 | 0.0049 |

| AQMS-NL04 | 0.92 | 0.000015 | 0.0039 | 0.0025 | |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.94 | 0.000015 | 0.0038 | 0.0026 |

| Method | Stations | R2 | RMSE (ppm) | MAE (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.77 | 0.0076 | 0.0061 | |

| AQMS-NL02 | 0.77 | 0.0071 | 0.0054 | |

| LR Ridge | AQMS-NL03 | 0.77 | 0.0085 | 0.0059 |

| AQMS-NL04 | 0.74 | 0.0069 | 0.0055 | |

| AQMS-NL05 | 0.70 | 0.0074 | 0.0058 | |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.79 | 0.0073 | 0.0059 | |

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.81 | 0.0068 | 0.0049 | |

| AQMS-NL02 | 0.80 | 0.0066 | 0.0046 | |

| LR Lasso | AQMS-NL03 | 0.70 | 0.0098 | 0.0068 |

| AQMS-NL04 | 0.79 | 0.0062 | 0.0044 | |

| AQMS-NL05 | 0.76 | 0.0065 | 0.0044 | |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.82 | 0.0068 | 0.0053 | |

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.88 | 0.0054 | 0.0037 | |

| AQMS-NL02 | 0.85 | 0.0058 | 0.0039 | |

| Random Forest | AQMS-NL03 | 0.67 | 0.0102 | 0.0066 |

| AQMS-NL04 | 0.82 | 0.0058 | 0.0042 | |

| AQMS-NL05 | 0.79 | 0.0061 | 0.0038 | |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.88 | 0.0054 | 0.0037 |

| Stations | R2 | MSE (ppm2) | RMSE (ppm) | MAE (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.89 | 0.000031 | 0.0056 | 0.0030 |

| AQMS-NL02 | 0.92 | 0.000024 | 0.0049 | 0.0029 |

| AQMS-NL03 | 0.90 | 0.000023 | 0.0048 | 0.0029 |

| AQMS-NL04 | 0.88 | 0.000028 | 0.0053 | 0.0031 |

| AQMS-NL05 | 0.94 | 0.000014 | 0.0037 | 0.0024 |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.95 | 0.000017 | 0.0041 | 0.0025 |

| Stations | R2 | MSE (ppm2) | RMSE (ppm) | MAE (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.86 | 0.000039 | 0.0063 | 0.0041 |

| AQMS-NL02 | 0.80 | 0.000043 | 0.0066 | 0.0041 |

| AQMS-NL03 | 0.71 | 0.000053 | 0.0073 | 0.0045 |

| AQMS-NL04 | 0.82 | 0.000036 | 0.0060 | 0.0039 |

| AQMS-NL05 | 0.79 | 0.000038 | 0.0062 | 0.0039 |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.83 | 0.000039 | 0.0063 | 0.0041 |

| Method | Stations | R2 | RMSE (ppm) | MAE (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.79 | 0.0072 | 0.0051 | |

| AQMS-NL02 | 0.77 | 0.0071 | 0.0048 | |

| LR Ridge | AQMS-NL03 | 0.67 | 0.0076 | 0.0050 |

| AQMS-NL04 | 0.77 | 0.0066 | 0.0047 | |

| AQMS-NL05 | 0.72 | 0.0070 | 0.0049 | |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.76 | 0.0074 | 0.0052 | |

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.79 | 0.0073 | 0.0049 | |

| AQMS-NL02 | 0.76 | 0.0072 | 0.0048 | |

| LR Lasso | AQMS-NL03 | 0.66 | 0.0078 | 0.0052 |

| AQMS-NL04 | 0.77 | 0.0067 | 0.0045 | |

| AQMS-NL05 | 0.72 | 0.0070 | 0.0046 | |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.76 | 0.0074 | 0.0050 | |

| AQMS-NL01 | 0.84 | 0.0062 | 0.0040 | |

| AQMS-NL02 | 0.79 | 0.0065 | 0.0040 | |

| Random Forest | AQMS-NL03 | 0.70 | 0.0074 | 0.0045 |

| AQMS-NL04 | 0.80 | 0.0061 | 0.0039 | |

| AQMS-NL05 | 0.76 | 0.0064 | 0.0039 | |

| AQMS-NL06 | 0.80 | 0.0065 | 0.0040 |

| Approach | Method | R2 | Air Pollutants | Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang et al. [34] | W-BiLSTM(PSO)-GRU + XGBoost | 0.94 | PM2.5, PM10, CO, SO2, O3 | 2013–2017 |

| Liu et al. [18] | XGBoost | 0.87 | PM2.5, PM10, CO, SO2, O3, NOx | 2023 |

| Jaurez et al. [23] | XGBoost | 0.61 | PM2.5, PM10, CO, SO2, O3, NOx, NO, NO2, NH3, Benzene, Toluene, Xylene | 2015–2020 |

| Dai et al. [19] | VAR-XGBoost | 0.95 | PM2.5, PM10, CO, SO2, O3, NO2 | 2016–2021 |

| Wei et al. [35] | XGBoost | 0.87 | PM2.5, PM10, CO, SO2, O3, NO2 | 2019–2023 |

| Experiment 1 | XGBoost | 0.83–0.96 | O3, NOx, NO, NO2 | 2022–2023 |

| Experiment 2 | XGBoost | 0.88–0.95 | O3, NOx, NO, NO2 | 2022–2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hernandez-Santiago, E.; Tello-Leal, E.; Jaramillo-Perez, J.M.; Macías-Hernández, B.A. Development of an Ozone (O3) Predictive Emissions Model Using the XGBoost Machine Learning Algorithm. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2026, 10, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010015

Hernandez-Santiago E, Tello-Leal E, Jaramillo-Perez JM, Macías-Hernández BA. Development of an Ozone (O3) Predictive Emissions Model Using the XGBoost Machine Learning Algorithm. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2026; 10(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernandez-Santiago, Esteban, Edgar Tello-Leal, Jailene Marlen Jaramillo-Perez, and Bárbara A. Macías-Hernández. 2026. "Development of an Ozone (O3) Predictive Emissions Model Using the XGBoost Machine Learning Algorithm" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 10, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010015

APA StyleHernandez-Santiago, E., Tello-Leal, E., Jaramillo-Perez, J. M., & Macías-Hernández, B. A. (2026). Development of an Ozone (O3) Predictive Emissions Model Using the XGBoost Machine Learning Algorithm. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 10(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010015