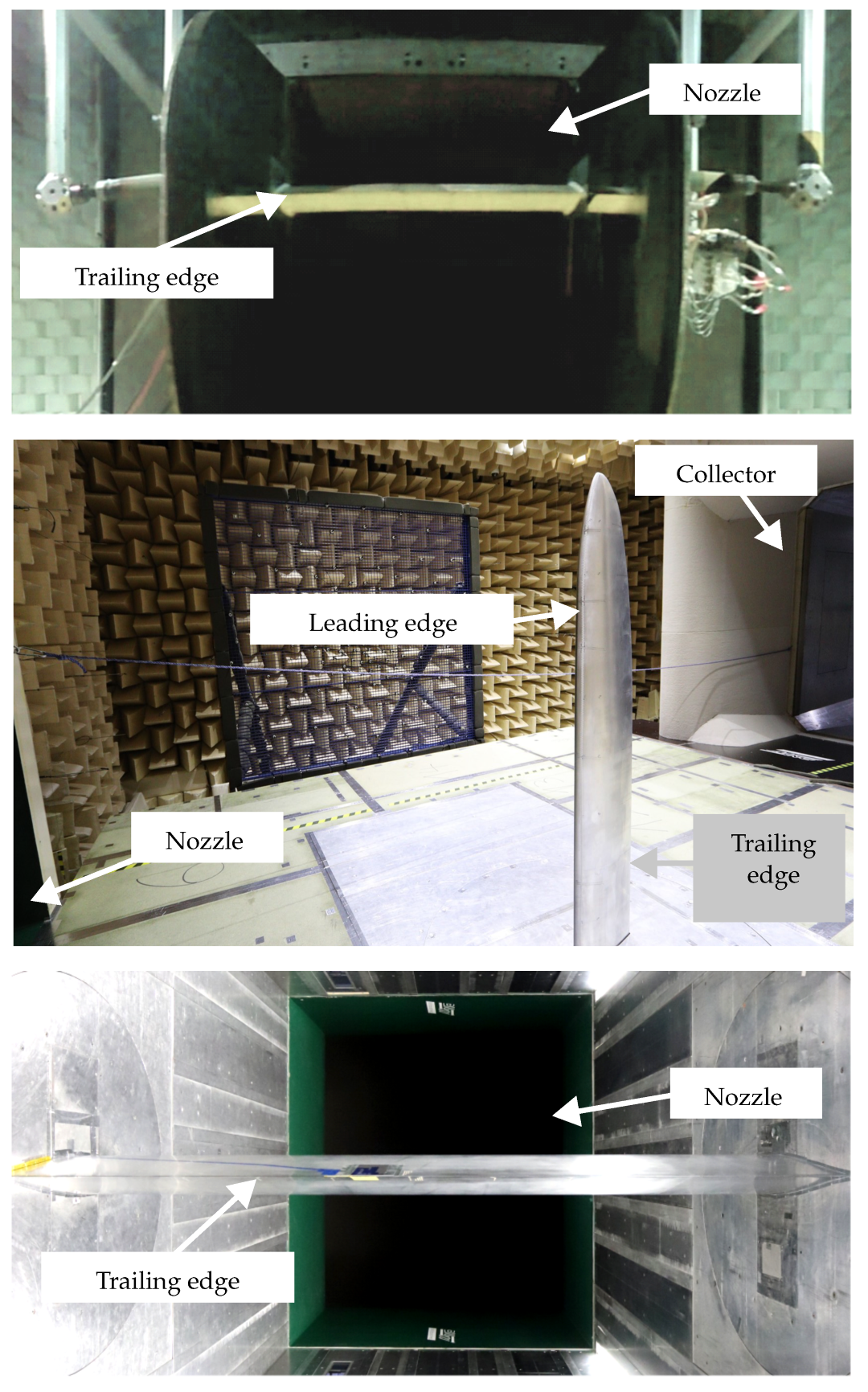

2.1. Experimental Setup and Data Collection

The data used in this study are based on previous studies by Herr and Suryadi et al. [

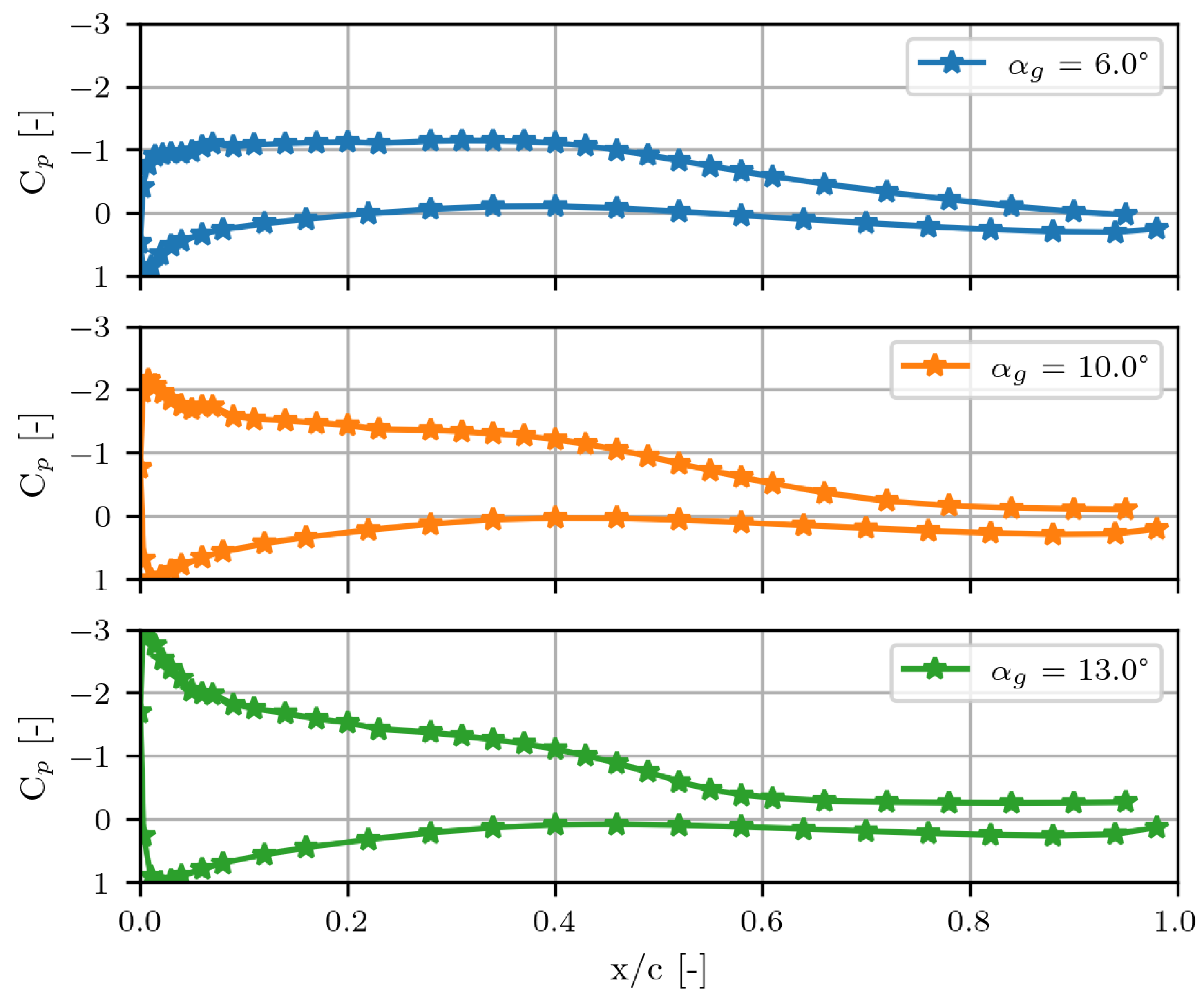

14,

15,

16]. The data were obtained experimentally in two different test facilities. These are the aeroacoustic wind tunnel (AWB) operated by DLR Institute of Aerodynamics and Flow Technology and the low-speed wind tunnel (NWB) operated by the German–Dutch Wind Tunnels Foundation. Both facilities are located at DLR Braunschweig. The AWB is an open-jet, closed-circuit aeroacoustic wind tunnel with an open test section and nozzle exit area of

. The maximum flow velocity at the nozzle exit is

. The NWB offers the options of an open, closed, or slotted test section with a test section area, or nozzle exit area in the case of an open test section, of

. For closed or slotted test sections, the maximum flow velocity reaches 90 m/s, and for the open-jet section, 80 m/s. In both facilities, the jet is treated with flow straighteners and turbulence control screens at the nozzle inlet to provide a flat velocity profile and reduce inflow turbulence. For more detailed description of the wind tunnels AWB and NWB, the readers are referred to [

17,

18].

In total, the datasets from three different wind tunnel models were utilized. These include 2.5D (no change in spanwise direction) and 3D models. The 2.5D wind tunnel models are based on the DU96-W-180 and NACA

airfoils, for which measurements were carried out in the AWB in an open test section and in the NWB in a closed test section. The 3D model is based on NACA 64-618 [

16] and was tested in the NWB using a three-quarter-open test section (with a floor from the nozzle to the collector).

Figure 1 illustrates the test setups for each airfoil.

Each of the three wind tunnel models has a different chord length

c and span length

b.

Table 1 summarizes key details of the wind tunnel models, including airfoil type, chord length

c, span length

b, and the tripping configuration (config). A clean configuration means that no manipulation was applied and the laminar–turbulent transition occurred naturally. The entry Tr-xxyy indicates that the laminar–turbulent transition was forced using a zig-zag band. Here, Tr denotes tripping, xx the position (in %) of the tripping band on the suction side, and yy the position of the tripping band on the pressure side. Information is also provided on the chord-based Reynolds numbers

, which were varied by changing the flow velocity

u∞. Furthermore, an overview of the variation in the AoA within each dataset is given. Note that in this study, AoA always refers to the geometric angle

set in the wind tunnel.

Each AoA was combined with each Reynolds number and each tripping configuration, resulting in 384 individual combinations, in which eight flush-mounted sensors captured the surface pressure fluctuations within the given chordwise range. The sensors were implemented in the wind tunnel model, mostly on the suction side, but occasionally also on the pressure side. As flow separation is expected only on the suction side, the measurements on the pressure side are not taken into account.

Table 2 provides an overview of the sensor types utilized within each measurement campaign, the number of sensors, the position in the chordwise direction, and the sampling rate.

The data from all these measurements were used for the development and evaluation of the flow prediction model. Specifically, the surface pressure fluctuations were used for this purpose for the entire acquisition time measured between

and

. In the low-frequency range, the data below 200 Hz are not reliable due to wind tunnel background noise and potential sensor installation-induced noise [

19]. In the upper frequency range, the data is limited to approximately 10,000 Hz due to the attenuating characteristics of the

-inch-diameter sensor (model GRAS 48LX-1, GRAS Sound & Vibration, Holte, Denmark) and due to the Helmholtz resonant frequency of sensor #1 (model LQ-062-0.35 BarA, Kulite Semiconductor Products, Leonia, NJ, USA) placed under a 0.5 mm diameter pinhole [

20].

2.2. Statistics of Surface Pressure Fluctuations

In wall turbulence analysis, a standard practice is to examine the probability density function (PDF) of the pressure fluctuations

, which provides insight into the occurrence, intensity, and symmetry of the fluctuations along the chord [

21]. To encompass the full dynamics of a separating turbulent boundary layer, a recent study [

3] compared a canonical flat plate and two different airfoils, including the DU96-W-180 used in the present study. As argued in [

3], non-stochastic high-amplitude events are likely caused by the formation of coherent structures present in separated flows. Typically, changes in the pressure fluctuation PDFs can be analyzed with the skewness

and kurtosis

along the chord, which represent the third and fourth moment of surface pressure fluctuations. On top of the classical spectral information, such time-domain criteria characterize the shape of the PDF of

, and certain thresholds of these high-order moments can ultimately be related to a flow map of either attached or separated flow as in [

2]. One of the long-term goals in wind energy applications is to monitor the occurrence of flow separation, which can lead to acoustically relevant events. Such detrimental flow conditions therefore require more detailed information about the flow status, ranging from a decelerated but still mean-attached boundary layer to weakly or largely separated states. Le Floc’h et al. [

3] indicated that massive flow separation is characterized by a dominant low-frequency contribution in the high-order moments. Unfortunately, such a distinction is presently impossible to achieve considering that the experimental limitations would have required resolution of frequencies lower than 100

[

3,

15].

Different types of instrumentation were also used: Kulite sensors for the DU96-W-180 case and GRAS ones for the two NACA profiles. Considering these experimental limitations, the objective is to confirm the global trends observed in [

2,

3], where the original time traces allowed the definition of thresholds for high-order moments, provided that convergence is achieved.

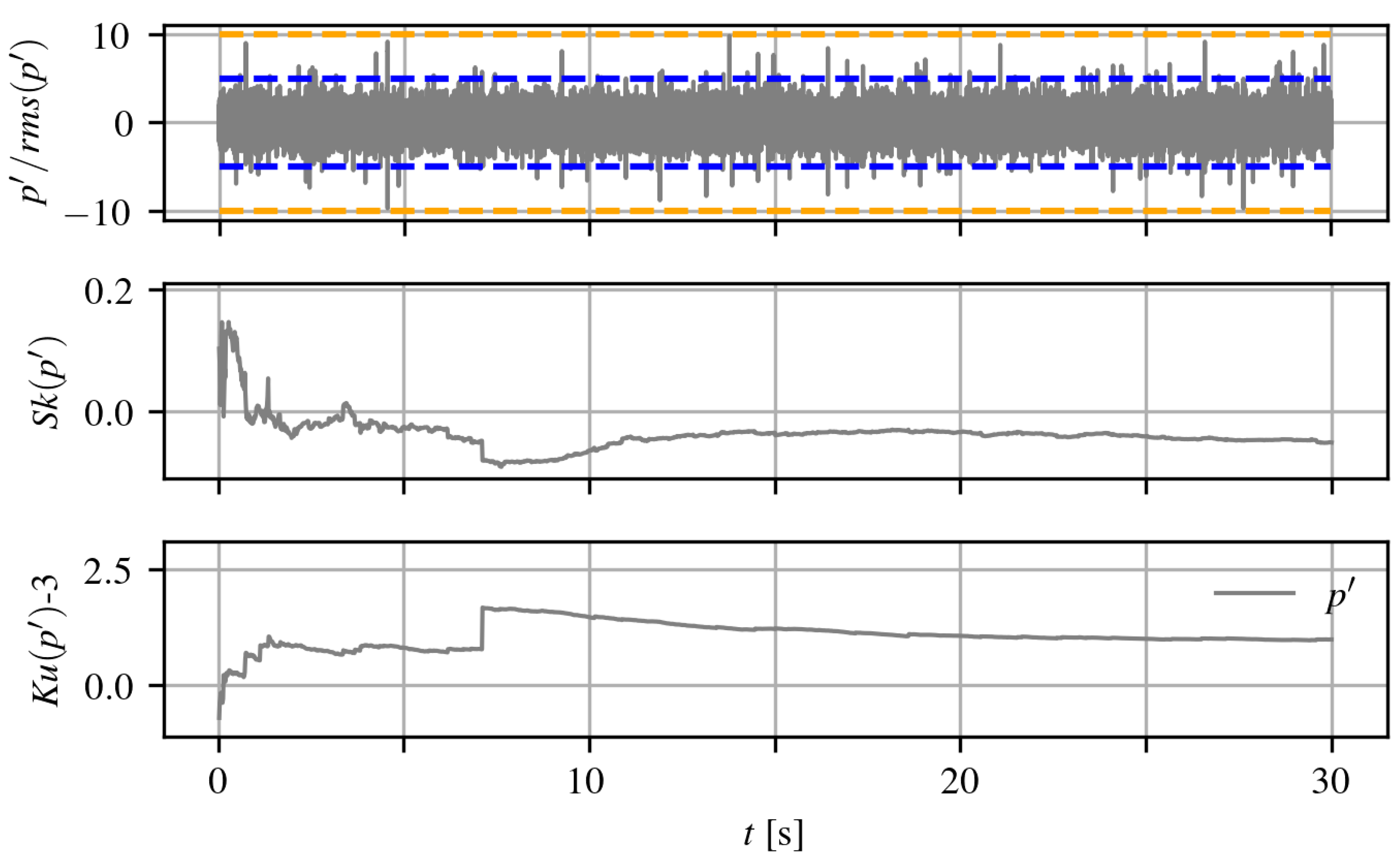

Figure 2 shows the normalized time trace

, where

denotes the root mean square of the pressure fluctuations, as well as the skewness

and kurtosis

for a case in which flow separation is present. This was measured for dataset #1 DU96-W-180 at

and

by a Kulite sensor located at

. The peaks typically observed range within

, which allows the cumulative skewness and kurtosis values to converge to an asymptotic value within a relatively narrow margin of about

and

, respectively. The high-order moments also consistently converge after approximately half the length of the time trace, i.e., after about 15

.

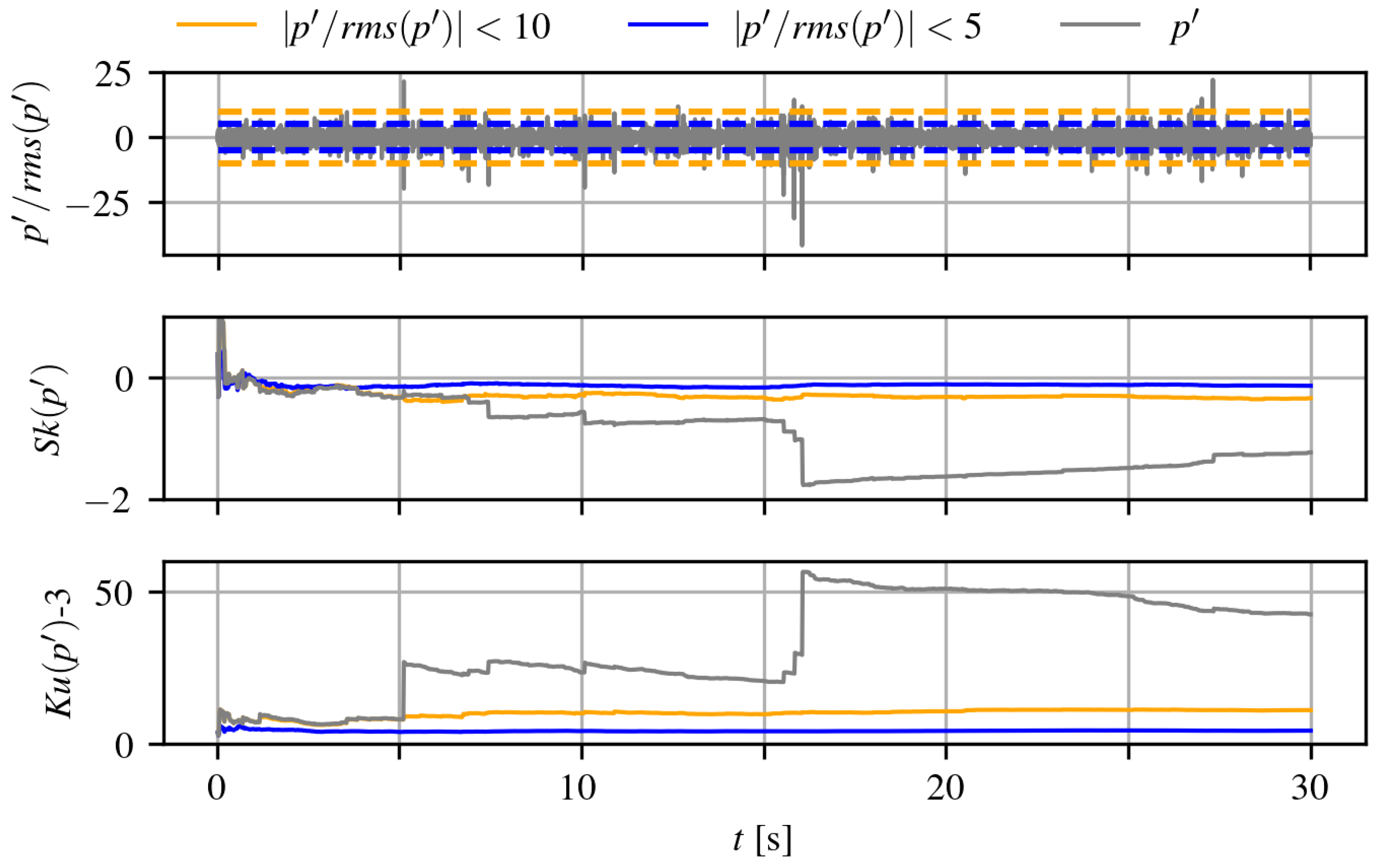

When analyzing dataset #3 with the NACA

airfoil, GRAS sensors recorded a comprehensive range of angles of attack and multiple inlet reference velocities. A typical result of these sensors at high AoA is shown in

Figure 3, where some visible differences can be noted when comparing it to

Figure 2, as the separated-flow conditions for the NACA

are observed at

. Unlike the results from the Kulite sensors, note the different scales of the y-axes. Indeed,

Figure 2 exhibits numerous instantaneous points with abnormally high-amplitude pressure peaks, which can be defined as

.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, such high values are not associated with coherent structures in the literature on separated flows and they are likely not connected to any physical motion. However, the immediate effect of such abnormal extreme values results in the poor convergence of both the cumulative skewness and kurtosis. When the events with and are excluded, a satisfactory convergence is obtained, and the upper threshold of 10 appears sufficient. Therefore, trimming these very-high-amplitude pressure peaks provides an adequate solution for amplitude correction and enables a better interpretation of results in the time domain.

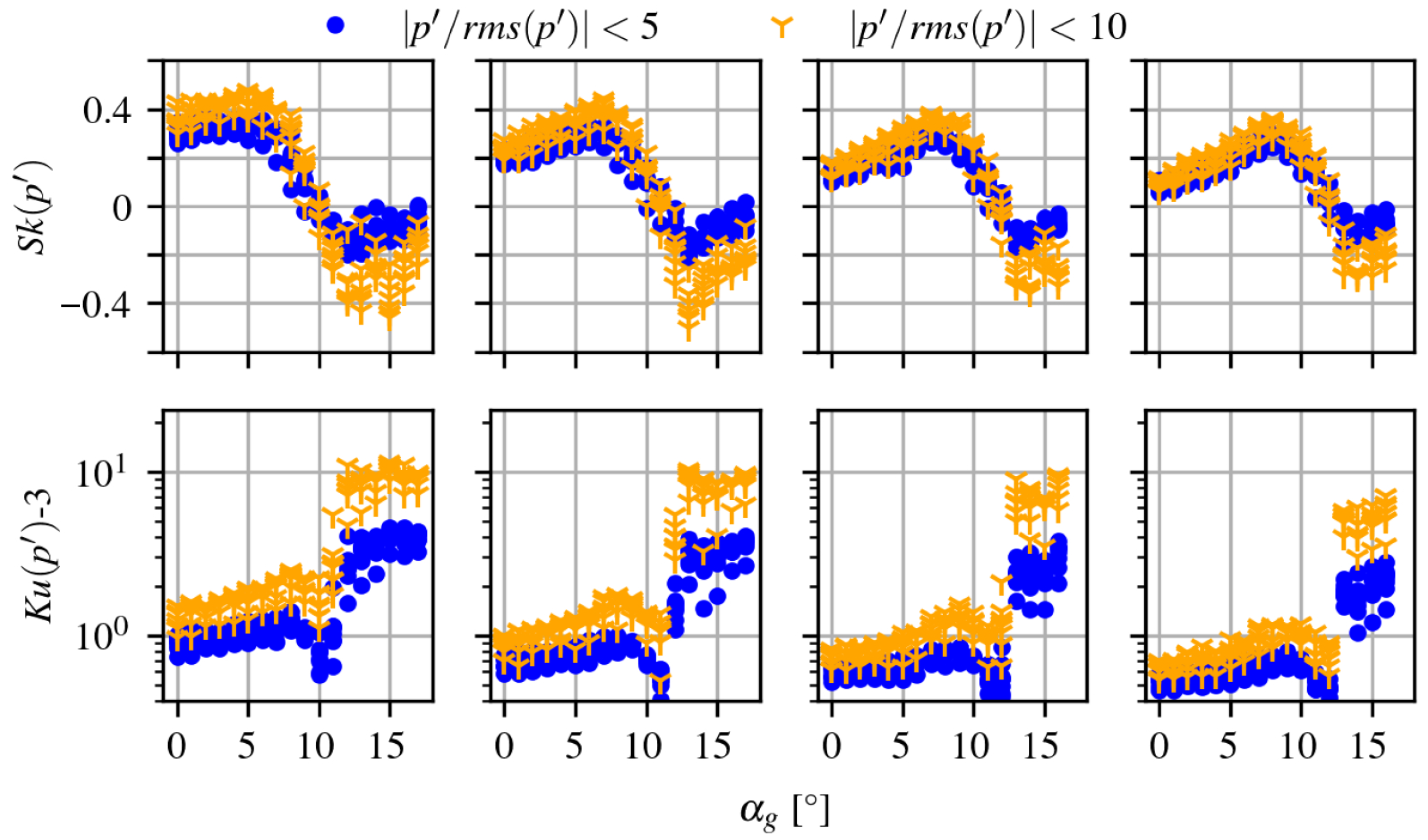

Figure 4 presents the skewness and kurtosis of the two different corrections of the time signals, where the very-high-amplitude pressure peaks were excluded using two thresholds,

and

. The wide array of measurements for the AoA allow the range

for the two Reynolds numbers

and

to be covered, as well as the range

for

. The trends are remarkably consistent with the global observations of Le Floc’h et al. [

3], where the onset of separation was characterized by positively skewed wall pressure.

In the present study, the full streamwise extent of the chord is not covered. Within each combination of measurements, eight sensors located in the last 25% of the chord simultaneously measured the surface pressure fluctuations from which skewness and kurtosis were calculated. It is worth noting here that the skewness and kurtosis values are remarkable for separated cases. With increasing AoA, a natural equivalence between a streamwise evolution toward the middle of a recirculation region and increasing values of

can be made in order to appreciate the effects of a progressively stronger flow separation. Beyond

, a switch from positive to negative skewness is observed for all cases. Consistently with [

3], the more negatively skewed values are obtained for the lowest velocities as they correspond to larger separation cases at

than at

. Regarding the kurtosis distribution, a first local peak is obtained for

, where the skewness reaches its positive maximum at the onset of separation. A second kurtosis peak occurs when the sign of the corresponding skewness abruptly switches from positive to negative as the vortex shedding unsteadiness is triggered in the recirculation region. With proximity to the trailing edge, skewness values decrease while kurtosis values increase. These features were also observed for the flat plate under massive flow separation, whereas no sign change in skewness was observed for an adverse-pressure-gradient turbulent boundary layer, still attached in a mean sense.

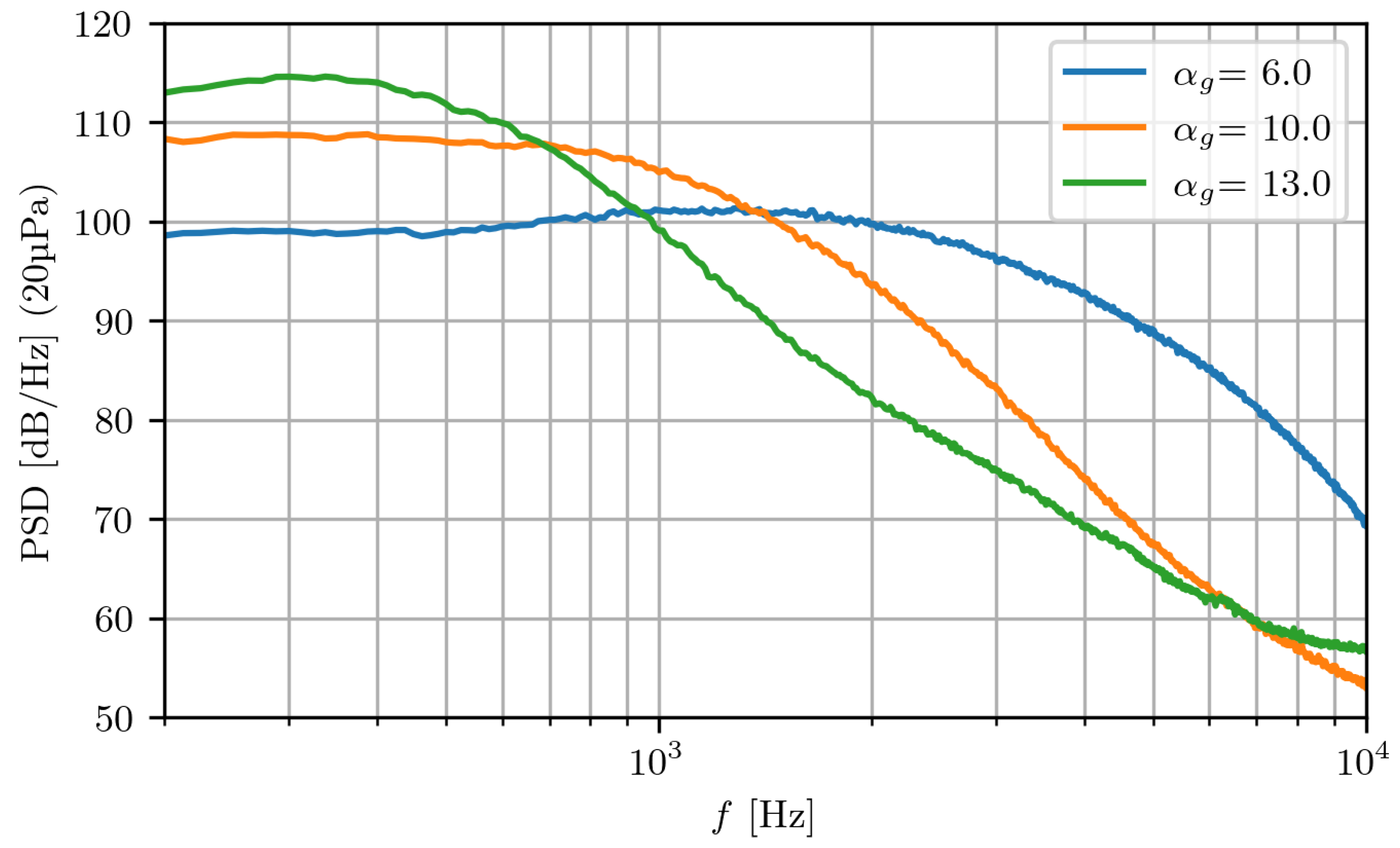

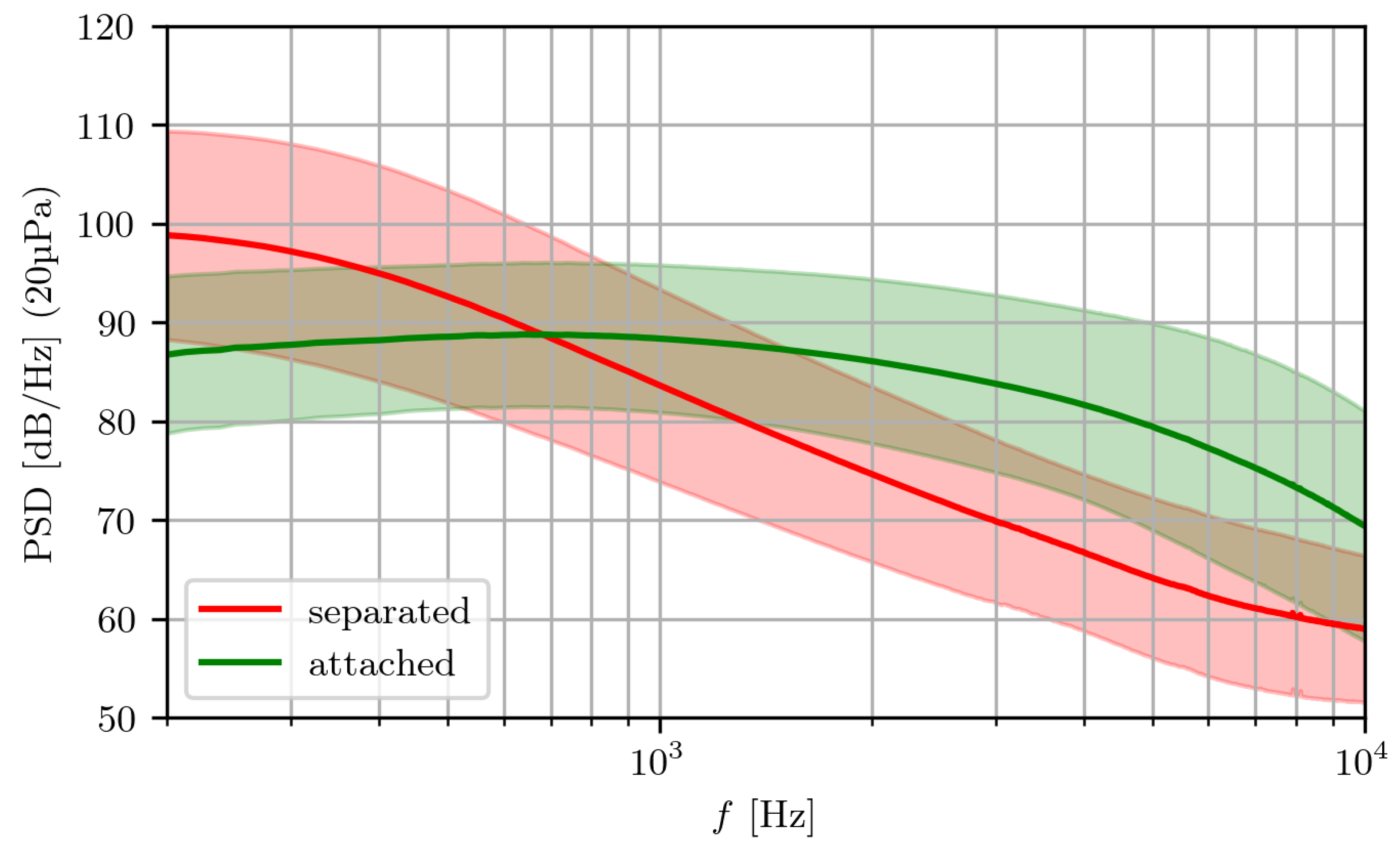

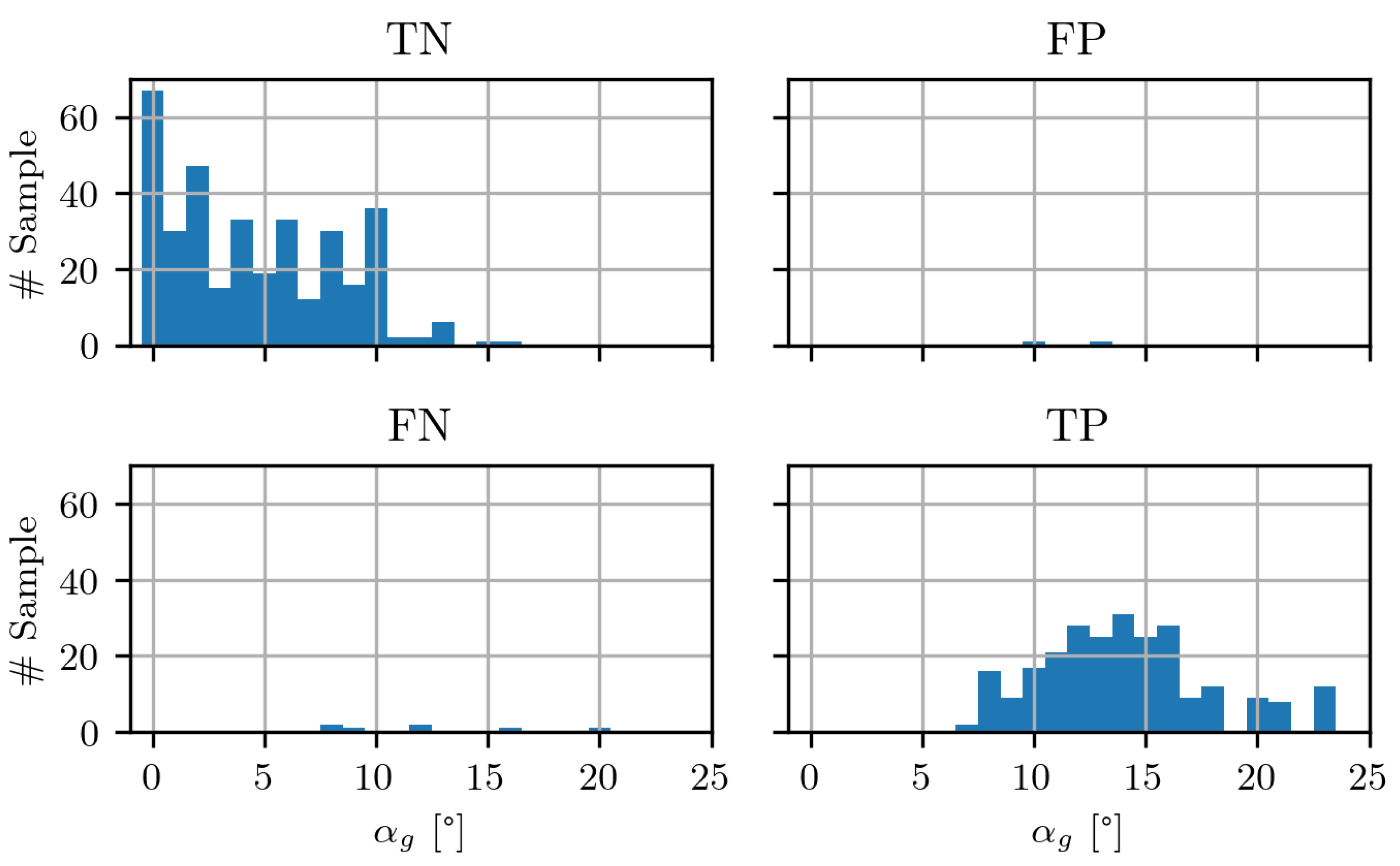

However, to obtain converged higher-order moments, a long time trace is necessary, which prohibits any separation detection in the case of real-time application. This limitation motivates a shift toward spectral features, which reduce the data volume and can be extracted on short time scales, potentially within a second, thus offering a more practical foundation for real-time prediction of separation. Beyond this immediate benefit, the use of spectral inputs also facilitates systematic comparisons across datasets and geometries, thereby strengthening both the robustness and the generalizability of machine-learning-based detection approaches.