A Recent Advance in the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Vaccine Development for Human Schistosomiasis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Schistosome Life Cycle

3. Signs, Symptoms, and Pathophysiology of Schistosomiasis

3.1. Signs and Symptoms of Schistosomiasis

3.2. Pathophysiology of Schistosomiasis

4. Distribution of Schistosoma Species and Schistosomiasis

| Schistosoma Species | Geographical Distribution | References |

|---|---|---|

| S. haematobium | Middle Eastern Africa | [9] |

| S. japonicum | Southeast Asia, Eastern Asia | [47] |

| S. mansoni | Southern America, Caribbean islands, Africa | [48] |

| Schistosoma margrebowiei, S. guineensis, S. intercalatum | Middle East, Africa | [49] |

| S. mekongi | Southeast Asia, Asia | [50] |

5. Morbidities and Co-Morbidities of Schistosomiasis

6. Recent Outbreaks of Schistosomiasis

7. Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis

7.1. Conventional Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis

7.2. Serological Methods

7.3. Advancement in the Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis

7.4. Proteins as Diagnostic Markers for Schistosomiasis

7.5. Nucleic Acid Test-Based Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis

7.6. PCR and Multiplex PCR

7.6.1. PCR-ELISA

7.6.2. Polymerase Chain Reaction in Real Time

7.6.3. PCR Recombinase Amplification

7.7. Antigen Test-Based Schistosomal Diagnosis

7.8. CRISPR/Cas13a-Based Assay for Detection of Schistosomiasis

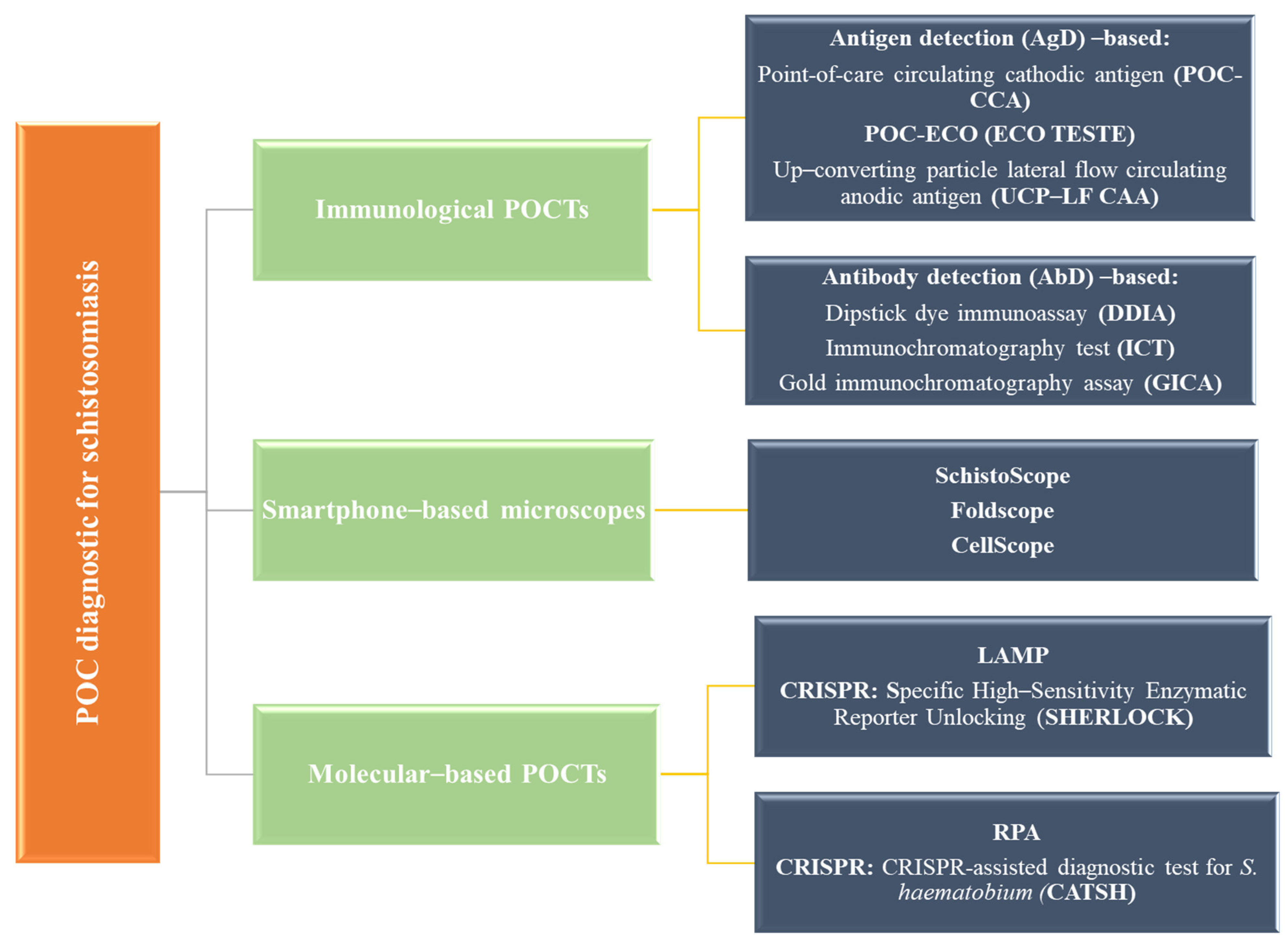

7.9. Point of Care (POC) and Other Emerging Methods

8. Prevention and Control of Schistosomiasis

9. Treatment of Schistosomiasis

10. Vaccine Development for Schistosomiasis with Possible Targets and Clinical Trials

10.1. S. haematobium 28 kDa Glutathione S-Transferases (Sh28GST)

10.2. S. mansoni Tetraspanin (Sm-TSP-2)

10.3. Schistosoma mansoni Calpain (Sm-p80)

10.4. S. mansoni 14 kDa Fatty Acid-Binding Protein [FABP] (Sm14)

| Techniques Used for the Identification of Vaccine Targets | Examples of Methods Applied | References |

|---|---|---|

| Gene editing | CRISPR/Cas-9 | [171] |

| Transcriptomics and DNA microarray profiling | RNA sequencing, next-generation sequencing | [172] |

| Proteomics | Reverse vaccinology approach, proteasomal cleavage and TAP transport prediction, epitope prediction, 3D structure prediction and refinement | [173] |

| Exosomics | - | [136,168] |

| Immunomics | ELISPOT, immunomic microarray, mapping tools for the epitopes of T and B cells | [174] |

| Immunoinformatics | Multi-epitope peptide-based, transmembrane proteins as a target | [173] |

| Gene suppression | iRNA, vector-based silencing, lentiviral transduction | [175] |

| Techniques used in vaccine delivery | Antibody and chromatography-based techniques | |

| DNA-based vaccines | SjCPTI, Smp80 | [175] |

| Irradiated cercarial vaccine | Culturing of cercariae, followed by irradiation | [176] |

| Synthetic multiple epitope peptides | Sm14 | [177] |

| Epitope based vaccine | Transmembrane proteins, codon optimization for E. coli to ensure heterologous expression and antigen purification, alongside stability and solubility prediction | [173] |

| Recombinant protein vaccines or bivalent vaccines | Smp80, Sm97, Sm14 (paramyosin), Sm-TSP-2, Sm14/Sm29, Sm14/Sm-TSP2/Sm29/Smp80 | [178] |

| New adjuvants | R848, TLR7/8 agonist, CpG-ODN, QuilA, GLA-SE, alum, poly (I: C) | [175] |

11. Vaccine Candidate in Experimental Trials

11.1. Surface Membrane Candidate Vaccines (Sm23)

11.2. Glucose Transporter Proteins (GTPs)

12. Challenges in Treatment and Vaccine Development for Schistosomiasis

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abs | Antibodies |

| AbD | Antibody detection |

| Ag | Antigen |

| AgD | Antigen detection |

| CATSH | CRISPR-assisted diagnostic test for S. haematobium |

| CAA | Circulating anodic antigen |

| CCA | Circulating cathodic antigen |

| DDIA | Dipstick dye immunoassay |

| FABP | Fatty acid-binding protein |

| GICA | Gold immunochromatography assay |

| FGS | Female genital schistosomiasis |

| GLA-SE | Glucopyranosyl lipid A in squalene emulsion |

| GTPs | Glucose transporter proteins |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| ICT | Immunochromatography test |

| ItS | Intestinal schistosomiasis |

| KKT | Kato–Katz technique |

| LAI | Long-acting injectable |

| LAMP | Loop-mediated isothermal amplification |

| LGIM | Lower gastrointestinal mucosa (LGIM) |

| MHT | Miracidium hatching test |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PCT | Preventive chemotherapy |

| POC | Point of care |

| POCT | Point-of-care test |

| PZQ | Praziquantel |

| RDTs | Rapid diagnostic tests |

| RPA | Recombinase polymerase amplification |

| SAC | School-aged children |

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Sh28GST | S. haematobium 28 kDa Glutathione S-Transferases |

| SHERLOCK | Specific high-sensitivity enzymatic reporter unlocking |

| Sm23 | Surface membrane 23 kDa |

| Smp80 | Schistosoma mansoni calpain |

| SmTSPs | Schistosoma mansoni tetraspanin |

| UGS | Urogenital schistosomiasis |

| UCP-LF CAA | Up-converting particle lateral flow circulating anodic antigen |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Lu, X.-T.; Gu, Q.-Y.; Limpanont, Y.; Song, L.-G.; Wu, Z.-D.; Okanurak, K.; Lv, Z.-Y. Snail-Borne Parasitic Diseases: An Update on Global Epidemiological Distribution, Transmission Interruption and Control Methods. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2018, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yang, K. The Global Status and Control of Human Schistosomiasis: An Overview. In Sino-African Cooperation for Schistosomiasis Control in Zanzibar: A Blueprint for Combating other Parasitic Diseases; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chala, B. Advances in Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis: Focus on Challenges and Future Approaches. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deol, A.K.; Fleming, F.M.; Calvo-Urbano, B.; Walker, M.; Bucumi, V.; Gnandou, I.; Tukahebwa, E.M.; Jemu, S.; Mwingira, U.J.; Alkohlani, A.; et al. Schistosomiasis—Assessing Progress toward the 2020 and 2025 Global Goals. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2519–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawa, P.A.; Kincaid-Smith, J.; Tukahebwa, E.M.; Webster, J.P.; Wilson, S. Schistosomiasis Morbidity Hotspots: Roles of the Human Host, the Parasite and Their Interface in the Development of Severe Morbidity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 635869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Launches New Guideline for the Control and Elimination of Human Schistosomiasis; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, C.; Rodríguez-Alonso, B.; López-Bernús, A.; Almeida, H.; Galindo-Pérez, I.; Velasco-Tirado, V.; Marcos, M.; Pardo-Lledías, J.; Belhassen-García, M. Clinical Spectrum of Schistosomiasis: An Update. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.G.; Vickers, D.; Olds, G.R.; Shah, S.M.; McManus, D.P. Katayama Syndrome. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007, 7, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cando, L.F.T.; Perias, G.A.S.; Tantengco, O.A.G.; Dispo, M.D.; Ceriales, J.A.; Girasol, M.J.G.; Leonardo, L.R.; Tabios, I.K.B. The Global Prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni, S. japonicum, and S. haematobium in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Lang, J.; Wang, B.; Liu, X.; Lu, Q.; He, J.; Gao, W.; Bing, P.; Tian, G.; Yang, J. TOOme: A Novel Computational Framework to Infer Cancer Tissue-of-Origin by Integrating Both Gene Mutation and Expression. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.; Pantelias, A.; Williamson, M.; Kjetland, E.F.; Krentel, A.; Gyapong, M.; Mbabazi, P.S.; Djirmay, A.G. Addressing a Silent and Neglected Scourge in Sexual and Reproductive Health in Sub-Saharan Africa by Development of Training Competencies to Improve Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Female Genital Schistosomiasis (FGS) for Health Workers. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, D.; Hotez, P.J.; Ducker, C.; Gyapong, M.; Bustinduy, A.L.; Secor, W.E.; Harrison, W.; Theobald, S.; Thomson, R.; Gamba, V.; et al. Integration of Prevention and Control Measures for Female Genital Schistosomiasis, HIV and Cervical Cancer. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M.; Bao, M.; He, B.; Zhou, X. LncRNA FAS-AS1 Upregulated by Its Genetic Variation Rs6586163 Promotes Cell Apoptosis in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma through Regulating Mitochondria Function and Fas Splicing. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; He, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, S.; Qi, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Ni, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, G.; et al. The Roles and Mechanism of M6A RNA Methylation Regulators in Cancer Immunity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruninger, S.K.; Rasamoelina, T.; Rakotoarivelo, R.A.; Razafindrakoto, A.R.; Rasolojaona, Z.T.; Rakotozafy, R.M.; Soloniaina, P.R.; Rakotozandrindrainy, N.; Rausche, P.; Doumbia, C.O.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Distribution of Schistosomiasis among Adults in Madagascar: A Cross-Sectional Study. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.-T. Review of Recent Prevalence of Urogenital Schistosomiasis in Sub-Saharan Africa and Diagnostic Challenges in the Field Setting. Life 2023, 13, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanyi, E.; Afolabi, A.S.; Onyango, N.O. Mathematical Modeling and Analysis of Transmission Dynamics and Control of Schistosomiasis. J. Appl. Math. 2021, 2021, 6653796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Jones, M.K.; Whitworth, D.J.; McManus, D.P. Innovations and Advances in Schistosome Stem Cell Research. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 599014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlder, E.L.; Costain, A.H.; Cook, P.C.; MacDonald, A.S. Schistosomes in the Lung: Immunobiology and Opportunity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 635513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Jin, Y. Single-Sex Schistosomiasis: A Mini Review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1158805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; McManus, D.P.; Hou, N.; Cai, P. Schistosome Infection and Schistosome-Derived Products as Modulators for the Prevention and Alleviation of Immunological Disorders. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 619776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Clec’h, W.; Chevalier, F.D.; McDew-White, M.; Menon, V.; Arya, G.-A.; Anderson, T.J.C. Genetic Architecture of Transmission Stage Production and Virulence in Schistosome Parasites. Virulence 2021, 12, 1508–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghani, E.; Zerpa, R.; Iliescu, G.; Escalante, C.P. Schistosomiasis and Liver Disease: Learning from the Past to Understand the Present. Clin. Case Rep. 2020, 8, 1522–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, D.P.; Bergquist, R.; Cai, P.; Ranasinghe, S.; Tebeje, B.M.; You, H. Schistosomiasis—From Immunopathology to Vaccines. Semin. Immunopathol. 2020, 42, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aula, O.P.; McManus, D.P.; Jones, M.K.; Gordon, C.A. Schistosomiasis with a Focus on Africa. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, J.D.; Kleppa, E.; Holmen, S.; Ndhlovu, P.D.; Mtshali, A.; Sebitloane, M.; Vennervald, B.J.; Gundersen, S.G.; Taylor, M.; Kjetland, E.F. The Association Between Female Genital Schistosomiasis and Other Infections of the Lower Genital Tract in Adolescent Girls and Young Women: A Cross-Sectional Study in South Africa. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2023, 27, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturt, A.; Webb, E.; Francis, S.; Hayes, R.; Bustinduy, A. Beyond the Barrier: Female Genital Schistosomiasis as a Potential Risk Factor for HIV-1 Acquisition. Acta Trop. 2020, 209, 105524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Seyler, B.C.; Chen, T.; Jian, W.; Fu, H.; Di, B.; Yip, W.; Pan, J. Disparity in Healthcare Seeking Behaviors between Impoverished and Non-Impoverished Populations with Implications for Healthcare Resource Optimization. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjetland, E.F.; Leutscher, P.D.C.; Ndhlovu, P.D. A Review of Female Genital Schistosomiasis. Trends Parasitol. 2012, 28, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, P.M.; Randrianasolo, B.S.; Feldmeier, H.; Chitsulo, L.; Ravoniarimbinina, P.; Roald, B.; Kjetland, E.F. Pathologic Mucosal Blood Vessels in Active Female Genital Schistosomiasis: New Aspects of a Neglected Tropical Disease. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2013, 32, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.L.; Fu, C.-L.; Pennington, L.F.; Honeycutt, J.D.; Odegaard, J.L.; Hsieh, Y.-J.; Hammam, O.; Conti, S.L.; Hsieh, M.H. A New Mouse Model for Female Genital Schistosomiasis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orish, V.N.; Morhe, E.K.S.; Azanu, W.; Alhassan, R.K.; Gyapong, M. The Parasitology of Female Genital Schistosomiasis. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector-Borne Dis. 2022, 2, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngassa, N.; Zacharia, A.; Lupenza, E.T.; Mushi, V.; Ngasala, B. Urogenital Schistosomiasis: Prevalence, Knowledge and Practices among Women of Reproductive Age in Northern Tanzania. IJID Reg. 2023, 6, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leutscher, P.D.C.; Høst, E.; Reimert, C.M. Semen Quality in Schistosoma haematobium Infected Men in Madagascar. Acta Trop. 2009, 109, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leutscher, P.; Ramarokoto, C.-E.; Reimert, C.; Feldmeier, H.; Esterre, P.; Vennervald, B.J. Community-Based Study of Genital Schistosomiasis in Men from Madagascar. Lancet 2000, 355, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Rana, M.; Choubey, P.; Kumar, S. Schistosoma japonicum Associated Colorectal Cancer and Its Management. Acta Parasitol. 2023, 68, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.L.; Santos, J.; Gouveia, M.J.; Bernardo, C.; Lopes, C.; Rinaldi, G.; Brindley, P.J.; da Costa, J.M.C. Review Urogenital Schistosomiasis—History, Pathogenesis, and Bladder Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, N.; Costa, J.M.; Brindley, P.J.; Santos, J.; Chaves, J.; Araujo, H. Comparison of Findings Using Ultrasonography and Cystoscopy in Urogenital Schistosomiasis in a Public Health Centre in Rural Angola: Research. S. Afr. Med. J. 2015, 105, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, S.D.; Norman, D.P.G.; Verdine, G.L. Structural Basis for Recognition and Repair of the Endogenous Mutagen 8-Oxoguanine in DNA. Nature 2000, 403, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, M.J.; Santos, J.; Brindley, P.J.; Rinaldi, G.; Lopes, C.; Santos, L.L.; da Costa, J.M.C.; Vale, N. Estrogen-like Metabolites and DNA-Adducts in Urogenital Schistosomiasis-Associated Bladder Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015, 359, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Figueiredo, J.C.; Basáñez, M.-G.; Khamis, I.S.; Garba, A.; Rollinson, D.; Stothard, J.R. Measuring Morbidity Associated with Urinary Schistosomiasis: Assessing Levels of Excreted Urine Albumin and Urinary Tract Pathologies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, H.; Bauerfeind, I. High Tissue Egg Burden Mechanically Impairing the Tubal Motility in Genital Schistosomiasis of the Female. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2003, 82, 970–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.M.; Mutapi, F.; Savill, N.J.; Woolhouse, M.E.J. Explaining Observed Infection and Antibody Age-Profiles in Populations with Urogenital Schistosomiasis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, C.; Cunha, M.C.; Santos, J.H.; da Costa, J.M.C.; Brindley, P.J.; Lopes, C.; Amado, F.; Ferreira, R.; Vitorino, R.; Santos, L.L. Insight into the Molecular Basis of Schistosoma haematobium-Induced Bladder Cancer through Urine Proteomics. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 11279–11287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołodziej, P.; Szostakowska, B.; Lass, A.; Sulima, M.; Sikorska, K.; Kocki, J.; Krupski, W.; Starownik, D.; Bojar, P.; Szumiło, J.; et al. Chronic Intestinal Schistosomiasis Caused by Co-Infection with Schistosoma Intercalatum and Schistosoma mansoni. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e196–e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumi, A.; Vogler, R.E.; Beltramino, A.A. The South-American Distribution and Southernmost Record of Biomphalaria Peregrina —A Potential Intermediate Host of Schistosomiasis. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Hou, L.; Qin, F.; Ren, Y.; Dong, B.; Zhu, D.; Li, H.; Lu, K.; Fu, Z.; Liu, J.; et al. Molecular and Functional Characterization of Schistosoma japonicum Annexin A13. Vet. Res. 2023, 54, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R.; Willingham, A. Status of Schistosomiasis Elimination in the Caribbean Region. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Schistosomiasis and Soil-Transmitted Helminthiases: Progress. Report, 2021; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Limpanont, Y.; Phuphisut, O.; Reamtong, O.; Adisakwattana, P. Recent Advances in Schistosoma Mekongi Ecology, Transcriptomics and Proteomics of Relevance to Snail Control. Acta Trop. 2020, 202, 105244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryseels, B.; Polman, K.; Clerinx, J.; Kestens, L. Human Schistosomiasis. Lancet 2006, 368, 1106–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, D.G.; Bustinduy, A.L.; Secor, W.E.; King, C.H. Human Schistosomiasis. Lancet 2014, 383, 2253–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.S.; Biedermann, P.; Ekpo, U.F.; Garba, A.; Mathieu, E.; Midzi, N.; Mwinzi, P.; N’Goran, E.K.; Raso, G.; Assaré, R.K.; et al. Spatial Distribution of Schistosomiasis and Treatment Needs in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Geostatistical Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Tuttle, M.S.; Powelson, J.; Vaughn, M.B.; Donovan, A.; Ward, D.M.; Ganz, T.; Kaplan, J. Hepcidin Regulates Cellular Iron Efflux by Binding to Ferroportin and Inducing Its Internalization. Science 2004, 306, 2090–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ye, Y.; Liao, Y. Functional Probes for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases. Aggregate 2024, e620, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molehin, A.J. Current Understanding of Immunity Against Schistosomiasis: Impact on Vaccine and Drug Development. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 2020, 11, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, V.J.; Samson, A.; Matungwa, D.J.; Kosia, A.L.; Ndubani, R.; Hussein, M.; Kalua, K.; Bustinduy, A.; Webster, B.; Bond, V.A.; et al. Female Genital Schistosomiasis Is a Women’s Issue, but Men Should Not Be Left out: Involving Men in Promoting Care for Female Genital Schistosomiasis in Mainland Tanzania. Front. Trop. Dis. 2024, 5, 1333862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaiah, P.M.; Palmeirim, M.S.; Steinmann, P. Epidemiology of Pediatric Schistosomiasis in Hard-to-Reach Areas and Populations: A Scoping Review Protocol. F1000Res 2022, 11, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayuni, S.A.; O’Ferrall, A.M.; Baxter, H.; Hesketh, J.; Mainga, B.; Lally, D.; Al-Harbi, M.H.; Lacourse, E.J.; Juziwelo, L.; Musaya, J.; et al. An Outbreak of Intestinal Schistosomiasis, alongside Increasing Urogenital Schistosomiasis Prevalence, in Primary School Children on the Shoreline of Lake Malawi, Mangochi District, Malawi. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumusiime, J.; Kagoro-Rugunda, G.; Tolo, C.U.; Namirembe, D.; Schols, R.; Hammoud, C.; Albrecht, C.; Huyse, T. An Accident Waiting to Happen? Exposing the Potential of Urogenital Schistosomiasis Transmission in the Lake Albert Region, Uganda. Parasit. Vectors 2023, 16, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidu, U.; Ibrahim, M.A.; de Koning, H.P.; McKerrow, J.H.; Caffrey, C.R.; Balogun, E.O. Human Schistosomiasis in Nigeria: Present Status, Diagnosis, Chemotherapy, and Herbal Medicines. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 2751–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-D.; Chen, H.-G.; Guo, J.-G.; Zeng, X.-J.; Hong, X.-L.; Xiong, J.-J.; Wu, X.-H.; Wang, X.-H.; Wang, L.-Y.; Xia, G.; et al. A Strategy to Control Transmission of Schistosoma japonicum in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Ponpetch, K.; Zhou, Y.-B.; Guo, J.; Erko, B.; Stothard, J.R.; Murad, M.H.; Zhou, X.-N.; Satrija, F.; Webster, J.P.; et al. Diagnosis of Schistosoma Infection in Non-Human Animal Hosts: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabello, A.L.T. Parasitological Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis Mansoni: Fecal Examination and Rectal Biopsy. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1992, 87, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noya, O.; Alarcón de Noya, B.; Losada, S.; Colmenares, C.; Guzmán, C.; Lorenzo, M.; Bermúdez, H. Laboratory Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis in Areas of Low Transmission: A Review of a Line of Research. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2002, 97, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberg, B. Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1985, 253, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barsoum, I.S.; Kamal, K.A.; Bassily, S.; Deelder, A.M.; Colley, D.G. Diagnosis of Human Schistosomiasis by Detection of Circulating Cathodic Antigen with a Monoclonal Antibody. J. Infect. Dis. 1991, 164, 1010–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olveda, R.M. Utility of Diagnostic Imaging in the Diagnosis and Management of Schistosomiasis. Clin. Microbiol. Open Access 2014, 3, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutapi, F. Improving Diagnosis of Urogenital Schistosome Infection. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2011, 9, 863–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Werf, M.J.; De Vlas, S.J. Diagnosis of Urinary Schistosomiasis: A Novel Approach to Compare Bladder Pathology Measured by Ultrasound and Three Methods for Hematuria Detection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004, 71, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Yin, X.; Hua, W.; Hou, M.; Ji, M.; Yu, C.; Wu, G. Application of DNA-Based Diagnostics in Detection of Schistosomal DNA in Early Infection and after Drug Treatment. Parasit. Vectors 2011, 4, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Fu, Z.; Li, C.; Han, Y.; Cao, X.; Han, H.; Liu, Y.; Lu, K.; Hong, Y.; Lin, J. Screening Diagnostic Candidates for Schistosomiasis from Tegument Proteins of Adult Schistosoma japonicum Using an Immunoproteomic Approach. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, B.R.; Barratt, J.; Lane, M.; Talundzic, E.; Bradbury, R.S. Sensitive Universal Detection of Blood Parasites by Selective Pathogen-DNA Enrichment and Deep Amplicon Sequencing. Microbiome 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, M.; Senghor, B.; Boissier, J.; Mulero, S.; Rey, O.; Portela, J. Development of Environmental Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (ELAMP) Diagnostic Tool for Bulinus Truncatus Field Detection. Parasit. Vectors 2023, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, S.G.; Gadd, G.; Coelho, F.S.; Cieplinski, A.; Emery, A.; Lugli, E.B.; Simões, T.C.; Fonseca, C.T.; Caldeira, R.L.; Webster, B. Laboratory and Field Validation of the Recombinase Polymerase Amplification Assay Targeting the Schistosoma mansoni Mitochondrial Minisatellite Region (SmMIT-RPA) for Snail Xenomonitoring for Schistosomiasis. Int. J. Parasitol. 2024, 54, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casacuberta-Partal, M.; Beenakker, M.; de Dood, C.J.; Hoekstra, P.T.; Kroon, L.; Kornelis, D.; Corstjens, P.; Hokke, C.H.; van Dam, G.J.; Roestenberg, M.; et al. Specificity of the Point-of-Care Urine Strip Test for Schistosoma Circulating Cathodic Antigen (POC-CCA) Tested in Non-Endemic Pregnant Women and Young Children. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 1412–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.O.; Sassa, M.; Parvin, N.; Islam, M.R.; Yajima, A.; Ota, E. Diagnostic Test Accuracy for Detecting Schistosoma japonicum and S. mekongi in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.L.; Eckhardt, M.; Krogan, N.J. Mass Spectrometry-based Protein–Protein Interaction Networks for the Study of Human Diseases. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2021, 17, e8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchuem Tchuenté, L.-A.; Rollinson, D.; Stothard, J.R.; Molyneux, D. Moving from Control to Elimination of Schistosomiasis in Sub-Saharan Africa: Time to Change and Adapt Strategies. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2017, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Song, L.; Xie, H.; Liang, J.; Yuan, D.; Wu, Z.; Lv, Z. Nucleic Acid Detection in the Diagnosis and Prevention of Schistosomiasis. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2016, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driscolla, A.J.; Kyle, J.L.; Remais, J. Development of a Novel PCR Assay Capable of Detecting a Single Schistosoma japonicum Cercaria Recovered from Oncomelania Hupensis. Parasitology 2005, 131, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Qadeer, A.; Rashid, M.; Rashid, M.I.; Cheng, G. Recent Advances in Nucleic Acid-Based Methods for Detection of Helminth Infections and the Perspective of Biosensors for Future Development. Parasitology 2020, 147, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.E.; Garcia Beltran, W.F.; Bard, A.Z.; Gogakos, T.; Anahtar, M.N.; Astudillo, M.G.; Yang, D.; Thierauf, J.; Fisch, A.S.; Mahowald, G.K.; et al. Clinical Sensitivity and Interpretation of PCR and Serological COVID-19 Diagnostics for Patients Presenting to the Hospital. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 13877–13884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guegan, H.; Fillaux, J.; Charpentier, E.; Robert-Gangneux, F.; Chauvin, P.; Guemas, E.; Boissier, J.; Valentin, A.; Cassaing, S.; Gangneux, J.-P.; et al. Real-Time PCR for Diagnosis of Imported Schistosomiasis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caliendo, A.M. Multiplex PCR and Emerging Technologies for the Detection of Respiratory Pathogens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, S326–S330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanlop, A.; Dang-Trinh, M.-A.; Kirinoki, M.; Suguta, S.; Shinozaki, K.; Kawazu, S. A Simple and Efficient Miracidium Hatching Technique for Preparing a Single-Genome DNA Sample of Schistosoma japonicum. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 84, 21–0536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, S.R.M.; Dias, I.H.L.; Fonseca, Á.L.S.; Contente, B.R.; Nogueira, J.F.C.; da Costa Oliveira, T.N.; Geiger, S.M.; Enk, M.J. Concordance of the Point-of-Care Circulating Cathodic Antigen Test for the Diagnosis of Intestinal Schistosomiasis in a Low Endemicity Area. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2019, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.-M.; Rong, R.; Lu, Z.-X.; Shi, C.-J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H.-Q.; Gong, W.; Luo, W. Schistosoma japonicum: A PCR Assay for the Early Detection and Evaluation of Treatment in a Rabbit Model. Exp. Parasitol. 2009, 121, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Guan, Z.-X.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.-Q.; Zhu, X.-Q.; He, Y.-K.; Xia, C.-M. DNA Detection of Schistosoma japonicum: Diagnostic Validity of a LAMP Assay for Low-Intensity Infection and Effects of Chemotherapy in Humans. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Gordon, C.A.; Williams, G.M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Gray, D.J.; Ross, A.G.; Harn, D.; McManus, D.P. Real-Time PCR Diagnosis of Schistosoma japonicum in Low Transmission Areas of China. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2018, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhou, K.; Li, Y.; Tong, L.; Yue, Y.; Zhou, K.; Liu, J.; Fu, Z.; Lin, J.; et al. Evaluation of a Real-Time PCR Assay for Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis Japonica in the Domestic Goat. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, C.-C.; Liu, J.-M.; Li, H.; Lu, K.; Fu, Z.-Q.; Zhu, C.-G.; Liu, Y.-P.; Tong, L.-B.; Zhou, D.; et al. Nested-PCR Assay for Detection of Schistosoma japonicum Infection in Domestic Animals. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2017, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.-J.; Zheng, H.-J.; Xu, J.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Wang, S.-Y.; Xia, C.-M. Sensitive and Specific Target Sequences Selected from Retrotransposons of Schistosoma japonicum for the Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.H.; Li, J.; Mo, X.H.; Li, X.Y.; Lin, R.Q.; Zou, F.C.; Weng, Y.B.; Song, H.Q.; Zhu, X.Q. The Second Transcribed Spacer RDNA Sequence: An Effective Genetic Marker for Inter-Species Phylogenetic Analysis of Trematodes in the Order Strigeata. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 111, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Wang, T.-P.; Furushima-Shimogawara, R.; Wen, L.; Kumagai, T.; Ohta, N.; Chen, R.; Ohmae, H. Detection of Early and Single Infections of Schistosoma japonicum in the Intermediate Host Snail, Oncomelania Hupensis, by PCR and Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Assay. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 83, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnops, L.; Tannich, E.; Polman, K.; Clerinx, J.; Van Esbroeck, M. Schistosoma Real-time PCR as Diagnostic Tool for International Travellers and Migrants. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2012, 17, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, N.; Baba, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Murakami, S. Global Analysis of Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit 1 (Cox1) Gene Variation in Dibothriocephalus Nihonkaiensis (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae). Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector-Borne Dis. 2021, 1, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Li, J.; Sugiyama, H.; Zhou, D.-H.; Song, H.-Q.; Zhao, G.-H.; Zhu, X.-Q. Genetic Variability among Schistosoma japonicum Isolates from the Philippines, Japan and China Revealed by Sequence Analysis of Three Mitochondrial Genes. Mitochondrial DNA 2015, 26, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobert, G.N.; Chai, M.; Duke, M.; McManus, D.P. Copro-PCR Based Detection of Schistosoma Eggs Using Mitochondrial DNA Markers. Mol. Cell Probes 2005, 19, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halili, S.; Grant, J.R.; Pilotte, N.; Gordon, C.A.; Williams, S.A. Development of a Novel Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for the Sensitive Detection of Schistosoma japonicum in Human Stool. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.-T.; Gu, M.-M.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Yu, Q.-F.; Lamberton, P.H.L.; Lu, D.-B. Meta-Analysis of Variable-Temperature PCR Technique Performance for Diagnosising Schistosoma japonicum Infections in Humans in Endemic Areas. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaenkham, U.; Waheed Abdullah, S.; Li, K.; Ullah, H.; Miu, K. Circulatory MicroRNAs in Helminthiases: Potent as Diagnostics Biomarker, Its Potential Role and Limitations. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1018872. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Y.; Cai, P.; Olveda, R.M.; Ross, A.G.; Olveda, D.U.; McManus, D.P. Parasite-Derived Circulating MicroRNAs as Biomarkers for the Detection of Human Schistosoma japonicum Infection. Parasitology 2020, 147, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lier, T.; GS, S.; Haaheim, H.; SO, H.; BJ, V.; MV, J. Novel Real Time PCR for Detection of Schistosoma japonicum in Stool. Southeast. Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2006, 37, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Tang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, R.; Lu, X.; Gong, L.; Wang, Y. A Highly Sensitive TaqMan Real-Time PCR Assay for Early Detection of Schistosoma Species. Acta Trop. 2011, 120, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, D.; Rothen, J.; Dangy, J.P.; Saner, C.; Daubenberger, C.; Allan, F.; Ame, S.M.; Ali, S.M.; Kabole, F.; Hattendorf, J.; et al. Performance of a Real-Time PCR Approach for Diagnosing Schistosoma haematobium Infections of Different Intensity in Urine Samples from Zanzibar. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mungai, P.L.; Muchiri, E.M.; King, C.H.; Abbasi, I.; Hamburger, J.; Kariuki, C. Differentiating Schistosoma haematobium from Related Animal Schistosomes by PCR Amplifying Inter-Repeat Sequences Flanking Newly Selected Repeated Sequences. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 87, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Arbab, S.; Li, K.; Khan, M.I.U.; Qadeer, A.; Muhammad, N. Schistosomiasis Related Circulating Cell-Free DNA: A Useful Biomarker in Diagnostics. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2022, 251, 111495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sady, H.; Al-Mekhlafi, H.; Ngui, R.; Atroosh, W.; Al-Delaimy, A.; Nasr, N.; Dawaki, S.; Abdulsalam, A.; Ithoi, I.; Lim, Y.; et al. Detection of Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma haematobium by Real-Time PCR with High Resolution Melting Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 16085–16103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.W.; Javed, B.; Khan, L. Analysis of Internal Transcribed Spacer1 (ITS1) Region of RDNA for Genetic Characterization of Paramphistomum sp. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5617–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwale, O.; Chia-Kwung, F.; Ezeh, C.; Gyang, P.; Haimo, S.; Hock, T.; Zheng, Q. Differentiating Schistosoma haematobium from Schistosoma Magrebowiei and Other Closely Related Schistosomes by Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification of a Species Specific Mitochondrial Gene. Trop. Parasitol. 2014, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, E.; Pérez, F.; Bello, I.; Bolívar, A.; Lares, M.; Osorio, A.; León, L.; Amarista, M.; Incani, R.N. Polymerase Chain Reaction for the Amplification of the 121-Bp Repetitive Sequence of Schistosoma mansoni: A Highly Sensitive Potential Diagnostic Tool for Areas of Low Endemicity. J. Helminthol. 2015, 89, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzo, E.; Midiri, A.; Manno, A.; Pastorello, M.; Biondo, C.; Mancuso, G. Insights into the Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Differential Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2024, 14, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, A.; Mazigo, H.D.; Mueller, A. Evaluation of Serum-Based Real-Time PCR to Detect Schistosoma mansoni Infection before and after Treatment. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuss, A.; Mazigo, H.D.; Mueller, A. Detection of Schistosoma mansoni DNA Using Polymerase Chain Reaction from Serum and Dried Blood Spot Card Samples of an Adult Population in North-Western Tanzania. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval, N.; Siles-Lucas, M.; Aban, J.L.; Pérez-Arellano, J.L.; Gárate, T.; Muro, A. Schistosoma mansoni: A Diagnostic Approach to Detect Acute Schistosomiasis Infection in a Murine Model by PCR. Exp. Parasitol. 2006, 114, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Juma, S.; Berquist, R.; Zhang, J.; Yang, K. Development and Performance of Recombinase-Aided Amplification (RAA) Assay for Detecting Schistosoma haematobium DNA in Urine Samples. Heliyon 2023, 9, e23031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanelt, B.; Adema, C.M.; Mansour, M.H.; Loker, E.S. Detection of Schistosoma mansoni in Biomphalaria Using Nested PCR. J. Parasitol. 1997, 83, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, N.; Siles-Lucas, M.; Perez-Arellano, J.L.; Carranza, C.; Puente, S.; Lopez-Aban, J.; Muro, A. A New PCR-Based Approach for the Specific Amplification of DNA from Different Schistosoma Species Applicable to Human Urine Samples. Parasitology 2006, 133, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, D.J.; Crellen, T.; Lamberton, P.H.L.; Allan, F.; Tracey, A.; Noonan, J.D.; Kabatereine, N.B.; Tukahebwa, E.M.; Adriko, M.; Holroyd, N.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Schistosoma mansoni Reveals Extensive Diversity with Limited Selection despite Mass Drug Administration. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, S.R.; McManus, D.P.; Sivakumaran, H.; Egwang, T.G.; Adriko, M.; Cai, P.; Gordon, C.A.; Duke, M.G.; French, J.D.; Collinson, N.; et al. Development of CRISPR/Cas13a-Based Assays for the Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis. EBioMedicine 2023, 94, 104730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Pan, H.; Feng, W. Ultrasensitive Photoelectric Immunoassay Platform Utilizing Biofunctional 2D Vertical SnS2/Ag2S Heterojunction. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 6005–6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, M.; Selvan Christyraj, J.R.S.; Venkatachalam, S.; Yesudhason, B.V.; Chelladurai, K.S.; Mohan, M.; Kalimuthu, K.; Narkhede, Y.B.; Christyraj, J.D.S. Foldscope Microscope, an Inexpensive Alternative Tool to Conventional Microscopy—Applications in Research and Education: A Review. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2022, 85, 3484–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Mu, Y.; Weerakoon, K.G.; Olveda, R.M.; Ross, A.G.; McManus, D.P. Performance of the Point-of-Care Circulating Cathodic Antigen Test in the Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis Japonica in a Human Cohort from Northern Samar, the Philippines. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Z.; Lv, S.; Tian, L.; Wang, W.; Jia, T. The Efficiency of Commercial Immunodiagnostic Assays for the Field Detection of Schistosoma japonicum Human Infections: A Meta-Analysis. Pathogens 2022, 11, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzón-García, M.P.; Cabeza-Barrera, M.I.; Lozano-Serrano, A.B.; Soriano-Pérez, M.J.; Castillo-Fernández, N.; Vázquez-Villegas, J.; Borrego-Jiménez, J.; Salas-Coronas, J. Accuracy of Three Serological Techniques for the Diagnosis of Imported Schistosomiasis in Real Clinical Practice: Not All in the Same Boat. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieri, O.S.; Bezerra, F.S.M.; Coelho, P.M.Z.; Enk, M.J.; Favre, T.C.; Graeff-Teixeira, C.; Oliveira, R.R.; Reis, M.G.d.; Andrade, L.S.d.A.; Beck, L.C.N.H.; et al. Accuracy of the Urine Point-of-Care Circulating Cathodic Antigen Assay for Diagnosing Schistosomiasis Mansoni Infection in Brazil: A Multicenter Study. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2023, 56, e0238-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodpai, R.; Sadaow, L.; Boonroumkaew, P.; Phupiewkham, W.; Thanchomnang, T.; Limpanont, Y.; Chusongsang, P.; Sanpool, O.; Ohmae, H.; Yamasaki, H.; et al. Comparison of Point-of-Care Test and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for Detection of Immunoglobulin G Antibodies in the Diagnosis of Human Schistosomiasis Japonica. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 107, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.S.; van Dam, G.J.; Pinheiro, M.C.C.; de Dood, C.J.; Peralta, J.M.; Peralta, R.H.S.; Daher, E.d.F.; Corstjens, P.L.A.M.; Bezerra, F.S.M. Performance of an Ultra-Sensitive Assay Targeting the Circulating Anodic Antigen (CAA) for Detection of Schistosoma mansoni Infection in a Low Endemic Area in Brazil. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodpai, R.; Sadaow, L.; Sanpool, O.; Boonroumkaew, P.; Thanchomnang, T.; Laymanivong, S.; Janwan, P.; Limpanont, Y.; Chusongsang, P.; Ohmae, H.; et al. Development and Accuracy Evaluation of Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Rapid Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis Mekongi in Humans. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2022, 22, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.-L.; Ding, J.-Z.; Wen, L.-Y.; Lou, D.; Yan, X.-L.; Lin, L.-J.; Lu, S.-H.; Lin, D.-D.; Zhou, X.-N. Development of a Rapid Dipstick with Latex Immunochromatographic Assay (DLIA) for Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis Japonica. Parasit. Vectors 2011, 4, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou-Fu, J.; Mu, S.; Xiao-Ping, Z.; Li, B.-L.; Yan-Yan, H.; Jing, L.; Tang, Y.-H.; Li, C. Evaluation of Partially Purified Soluble Egg Antigens in Colloidal Gold Immunochromatography Assay Card for Rapid Detection of Anti-Schistosoma japonicum Antibodies. Southeast. Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2014, 568, 568–575. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, M.S.; Tedla, B.A.; Mekonnen, G.G.; Proietti, C.; Becker, L.; Nakajima, R.; Jasinskas, A.; Doolan, D.L.; Amoah, A.S.; Knopp, S.; et al. Immunomics-Guided Discovery of Serum and Urine Antibodies for Diagnosing Urogenital Schistosomiasis: A Biomarker Identification Study. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e617–e626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunamoorthi, K.; Almalki, M.; Ghailan, K. Schistosomiasis: A Neglected Tropical Disease of Poverty: A Call for Intersectoral Mitigation Strategies for Better Health. J. Health Res. Rev. 2018, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokaliaris, C.; Garba, A.; Matuska, M.; Bronzan, R.N.; Colley, D.G.; Dorkenoo, A.M.; Ekpo, U.F.; Fleming, F.M.; French, M.D.; Kabore, A.; et al. Effect of Preventive Chemotherapy with Praziquantel on Schistosomiasis among School-Aged Children in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Spatiotemporal Modelling Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, M.; Liang, H.; Long, X.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Chen, Q. Understanding the Pathophysiology of Exosomes in Schistosomiasis: A New Direction for Disease Control and Prevention. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 634138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, N.; Gouveia, M.J.; Rinaldi, G.; Brindley, P.J.; Gärtner, F.; Correia da Costa, J.M. Praziquantel for Schistosomiasis: Single-Drug Metabolism Revisited, Mode of Action, and Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montresor, A.; Engels, D.; Chitsulo, L.; Bundy, D.A.P.; Brooker, S.; Savioli, L. Development and Validation of a ‘Tablet Pole’ for the Administration of Praziquantel in Sub-Saharan Africa. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2001, 95, 542–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushige, M.; Chase-Topping, M.; Woolhouse, M.E.J.; Mutapi, F. Efficacy of Praziquantel Has Been Maintained over Four Decades (from 1977 to 2018): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Factors Influence Its Efficacy. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnkugwe, R.H.; Minzi, O.; Kinung’hi, S.; Kamuhabwa, A.; Aklillu, E. Effect of Pharmacogenetics Variations on Praziquantel Plasma Concentrations and Schistosomiasis Treatment Outcomes Among Infected School-Aged Children in Tanzania. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 712084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muok, E.M.O.; Were, V.O.; Obonyo, C.O. Efficacy of a Single Oral Dose of Artesunate plus Sulfalene-Pyrimethamineversus Praziquantel in the Treatment of Schistosoma mansoni in Kenyan Children: An Open-Label, Randomized, Exploratory Trial. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2024, 110, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obonyo, C.O.; Were, V.O.; Wamae, P.; Muok, E.M.O. SCHISTOACT: A Protocol for an Open-Label, Five-Arm, Non-Inferiority, Individually Randomized Controlled Trial of the Efficacy and Safety of Praziquantel plus Artemisinin-Based Combinations in the Treatment of Schistosoma mansoni Infection. Trials 2023, 24, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minzi, O.M.; Mnkugwe, R.H.; Ngaimisi, E.; Kinung’hi, S.; Hansson, A.; Pohanka, A.; Kamuhabwa, A.; Aklillu, E. Effect of Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine on the Pharmacokinetics of Praziquantel for Treatment of Schistosoma mansoni Infection. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Deng, L.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, W.; Fan, X. Molluscicides against the Snail-Intermediate Host of Schistosoma: A Review. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 3355–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, K.; Mtalitinya, G.S.; Aristide, C.; Airewele, E.A.; Nyakaru, D.K.; McMahon, P.; Mulaki, G.M.; Corstjens, P.L.A.M.; de Dood, C.J.; van Dam, G.J.; et al. Effects of Schistosoma mansoni and Praziquantel Treatment on the Lower Gastrointestinal Mucosa: A Cohort Study in Tanzania. Acta Trop. 2023, 238, 106752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godman, B.; McCabe, H.; D Leong, T.; Mueller, D.; Martin, A.P.; Hoxha, I.; Mwita, J.C.; Rwegerera, G.M.; Massele, A.; Costa, J.d.O.; et al. Fixed Dose Drug Combinations—Are They Pharmacoeconomically Sound? Findings and Implications Especially for Lower- and Middle-Income Countries. Expert. Rev. Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020, 20, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrmann, S.; Szlezák, N.; Faucher, J.; Matsiegui, P.; Neubauer, R.; Binder, R.K.; Lell, B.; Kremsner, P.G. Artesunate and Praziquantel for the Treatment of Schistosoma haematobium Infections: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. J. Infect. Dis. 2001, 184, 1363–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, J.; N’Guessan, N.A.; Adoubryn, K.D.; Silué, K.D.; Vounatsou, P.; Hatz, C.; Utzinger, J.; N’Goran, E.K. Efficacy and Safety of Mefloquine, Artesunate, Mefloquine-Artesunate, and Praziquantel against Schistosoma haematobium: Randomized, Exploratory Open-Label Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-J.; Zhou, X.-N. A New Formulation of Praziquantel to Achieve Schistosomiasis Elimination. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 774–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K.; Patel, M.M.; Mehta, P.J. Long-Acting Injectables: Current Perspectives and Future Promise. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2019, 36, 137–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Cheng, L.; Hou, J.; Guo, S.; Zhu, C.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, J. Prevention of Schistosoma japonicum Infection in Mice with Long-Acting Praziquantel Implants. Exp. Parasitol. 2012, 131, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, E.L.; Edielu, A.; Wu, H.W.; Kabatereine, N.B.; Tukahebwa, E.M.; Mubangizi, A.; Adriko, M.; Elliott, A.M.; Hope, W.W.; Mawa, P.A.; et al. The Praziquantel in Preschoolers (PIP) Trial: Study Protocol for a Phase II PK/PD-Driven Randomised Controlled Trial of Praziquantel in Children under 4 Years of Age. Trials 2021, 22, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, N.C.; Bezerra, F.S.M.; Colley, D.G.; Fleming, F.M.; Homeida, M.; Kabatereine, N.; Kabole, F.M.; King, C.H.; Mafe, M.A.; Midzi, N.; et al. Review of 2022 WHO Guidelines on the Control and Elimination of Schistosomiasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22, e327–e335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekiya, T.A.; Kumar, P.; Kondiah, P.P.D.; Pillay, V.; Choonara, Y.E. Synthesis and Therapeutic Delivery Approaches for Praziquantel: A Patent Review (2010-Present). Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 31, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obonyo, C.O.; Muok, E.M.; Were, V. Biannual Praziquantel Treatment for Schistosomiasis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD013412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molehin, A.J. Schistosomiasis Vaccine Development: Update on Human Clinical Trials. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulanger, D.; Warter, A.; Sellin, B.; Lindner, V.; Pierce, R.J.; Chippaux, J.-P.; Capron, A. Vaccine Potential of a Recombinant Glutathione S-Transferase Cloned from Schistosoma haematobium in Primates Experimentally Infected with an Homologous Challenge. Vaccine 1999, 17, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, A.X.; Agosti, J.M.; Walson, J.L.; Hall, B.F.; Gordon, L. Schistosomiasis Elimination Strategies and Potential Role of a Vaccine in Achieving Global Health Goals. Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 90, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveau, G.; Schacht, A.-M.; Dompnier, J.-P.; Deplanque, D.; Seck, M.; Waucquier, N.; Senghor, S.; Delcroix-Genete, D.; Hermann, E.; Idris-Khodja, N.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the RSh28GST Urinary Schistosomiasis Vaccine: A Phase 3 Randomized, Controlled Trial in Senegalese Children. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.H.; Pearson, M.S.; Bethony, J.M.; Smyth, D.J.; Jones, M.K.; Duke, M.; Don, T.A.; McManus, D.P.; Correa-Oliveira, R.; Loukas, A. Tetraspanins on the Surface of Schistosoma mansoni Are Protective Antigens against Schistosomiasis. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, C.S.; Ribeiro, A.P.D.; Cardoso, F.C.; Martins, V.P.; Figueiredo, B.C.P.; Assis, N.R.G.; Morais, S.B.; Caliari, M.V.; Loukas, A.; Oliveira, S.C. A Multivalent Chimeric Vaccine Composed of Schistosoma mansoni SmTSP2 and Sm29 Was Able to Induce Protection against Infection in Mice. Parasite Immunol. 2014, 36, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemert, D.J.; Correa-Oliveira, R.; Fraga, C.G.; Talles, F.; Silva, M.R.; Patel, S.M.; Galbiati, S.; Kennedy, J.K.; Lundeen, J.S.; Gazzinelli, M.F.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Phase 1b Trial of the Sm-TSP-2 Vaccine for Intestinal Schistosomiasis in Healthy Brazilian Adults Living in an Endemic Area. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, J.U.; Melkus, M.W.; Kottapalli, K.R.; Okiya, O.E.; Sudduth, J.; Zhang, W.; Molehin, A.J.; Carter, D.; Siddiqui, A.A. Sm-P80-Based Schistosomiasis Vaccine Mediated Epistatic Interactions Identified Potential Immune Signatures for Vaccine Efficacy in Mice and Baboons. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Molehin, A.J.; Rojo, J.U.; Sudduth, J.; Ganapathy, P.K.; Kim, E.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Freeborn, J.; Sennoune, S.R.; May, J.; et al. Sm-p80-based Schistosomiasis Vaccine: Double-blind Preclinical Trial in Baboons Demonstrates Comprehensive Prophylactic and Parasite Transmission-blocking Efficacy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1425, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tendler, M.; Brito, C.A.; Vilar, M.M.; Serra-Freire, N.; Diogo, C.M.; Almeida, M.S.; Delbem, A.C.; Da Silva, J.F.; Savino, W.; Garratt, R.C.; et al. A Schistosoma mansoni Fatty Acid-Binding Protein, Sm14, Is the Potential Basis of a Dual-Purpose Anti-Helminth Vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini-Oliveira, M.; Machado Pinto, P.; Santos, T.d.; Vilar, M.M.; Grinsztejn, B.; Veloso, V.; Paes-de-Almeida, E.C.; Amaral, M.A.Z.; Ramos, C.R.; Marroquin-Quelopana, M.; et al. Development of the Sm14/GLA-SE Schistosomiasis Vaccine Candidate: An Open, Non-Placebo-Controlled, Standardized-Dose Immunization Phase Ib Clinical Trial Targeting Healthy Young Women. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perocheau, D.; Touramanidou, L.; Gurung, S.; Gissen, P.; Baruteau, J. Clinical Applications for Exosomes: Are We There Yet? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 2375–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.; Almeida, F. Exosome-Based Vaccines: History, Current State, and Clinical Trials. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 711565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Qian, N.P.M.; Yannarelli, G. Advances in Innovative Exosome-Technology for Real Time Monitoring of Viable Drugs in Clinical Translation, Prognosis and Treatment Response. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučuk, N.; Primožič, M.; Knez, Ž.; Leitgeb, M. Exosomes Engineering and Their Roles as Therapy Delivery Tools, Therapeutic Targets, and Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigal, S.; Chappell, P.; Palumbo, D.; Lubaczewski, S.; Ramaker, S.; Abbas, R. Diagnosis and Treatment Options for Preschoolers with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 30, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahum, L.A.; Mourão, M.M.; Oliveira, G. New Frontiers in Schistosoma Genomics and Transcriptomics. J. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 2012, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, R.C.O.; Tiwari, S.; Ferreira, L.C.G.; Oliveira, F.M.; Lopes, M.D.; Passos, M.J.F.; Maia, E.H.B.; Taranto, A.G.; Kato, R.; Azevedo, V.A.C.; et al. Immunoinformatics Design of Multi-Epitope Peptide-Based Vaccine Against Schistosoma mansoni Using Transmembrane Proteins as a Target. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 621706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, L.P.; Vance, G.M.; Coulson, P.S.; Vitoriano-Souza, J.; Neto, A.P.d.S.; Wangwiwatsin, A.; Neves, L.X.; Castro-Borges, W.; McNicholas, S.; Wilson, K.S.; et al. Epitope Mapping of Exposed Tegument and Alimentary Tract Proteins Identifies Putative Antigenic Targets of the Attenuated Schistosome Vaccine. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 624613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molehin, A.J.; McManus, D.P.; You, H. Vaccines for Human Schistosomiasis: Recent Progress, New Developments and Future Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, D.J.; Ndao, M. Promising Technologies in the Field of Helminth Vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 711650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, A.A.M.; Ribeiro, A.J.; Resende, C.A.A.; Couto, C.A.P.; Gandra, I.B.; dos Santos Barcelos, I.C.; da Silva, J.O.; Machado, J.M.; Silva, K.A.; Silva, L.S.; et al. Recombinant Multiepitope Proteins Expressed in Escherichia Coli Cells and Their Potential for Immunodiagnosis. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, A.; Baee, M.; Rostamtabar, M.; Karkhah, A.; Alizadeh, S.; Tourani, M.; Nouri, H.R. Development of a Conserved Chimeric Vaccine Based on Helper T-Cell and CTL Epitopes for Induction of Strong Immune Response against Schistosoma mansoni Using Immunoinformatics Approaches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 141, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Osses, I.; Reichembach, L.H.; Ramirez, M.I. Exosomes or Microvesicles? Two Kinds of Extracellular Vesicles with Different Routes to Modify Protozoan-Host Cell Interaction. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 3567–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naseri, A.; Al-Absi, S.; El Ridi, R.; Mahana, N. A Comprehensive and Critical Overview of Schistosomiasis Vaccine Candidates. J. Parasit. Dis. 2021, 45, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyayu, T.; Zeleke, A.J.; Worku, L. Current Status and Future Prospects of Protein Vaccine Candidates against Schistosoma mansoni Infection. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2020, 11, e00176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrifield, M.; Hotez, P.J.; Beaumier, C.M.; Gillespie, P.; Strych, U.; Hayward, T.; Bottazzi, M.E. Advancing a Vaccine to Prevent Human Schistosomiasis. Vaccine 2016, 34, 2988–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onile, O.S.; Fadare, S.O.; Omitogun, G.O. Selection of T Cell Epitopes from S. mansoni Sm23 Protein as a Vaccine Construct, Using Immunoinformatics Approach. J. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. Res. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woellner-Santos, D.; Tahira, A.C.; Malvezzi, J.V.M.; Mesel, V.; Morales-Vicente, D.A.; Trentini, M.M.; Marques-Neto, L.M.; Matos, I.A.; Kanno, A.I.; Pereira, A.S.A.; et al. Schistosoma mansoni Vaccine Candidates Identified by Unbiased Phage Display Screening in Self-Cured Rhesus Macaques. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, B.C.-P.; Ricci, N.D.; de Assis, N.R.G.; de Morais, S.B.; Fonseca, C.T.; Oliveira, S.C. Kicking in the Guts: Schistosoma mansoni Digestive Tract Proteins Are Potential Candidates for Vaccine Development. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, S.B.; Figueiredo, B.C.; Assis, N.R.G.; Homan, J.; Mambelli, F.S.; Bicalho, R.M.; Souza, C.; Martins, V.P.; Pinheiro, C.S.; Oliveira, S.C. Schistosoma mansoni SmKI-1 or Its C-Terminal Fragment Induces Partial Protection against S. mansoni Infection in Mice. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Molehin, A.; Patel, P.; Kim, E.; Peña, A.; Siddiqui, A.A. Testing of Schistosoma mansoni Vaccine Targets. In Schistosoma mansoni: Methods and Protocols; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 229–262. [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar, S.; Zhang, W.; Ahmad, G.; Torben, W.; Alam, M.U.; Le, L.; Damian, R.T.; Wolf, R.F.; White, G.L.; Carey, D.W.; et al. Cross-Species Protection: Schistosoma mansoni Sm-P80 Vaccine Confers Protection against Schistosoma haematobium in Hamsters and Baboons. Vaccine 2014, 32, 1296–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosnier, C.; Brandt, C.; Rinaldi, G.; McCarthy, C.; Barker, C.; Clare, S.; Berriman, M.; Wright, G.J. Systematic Screening of 96 Schistosoma mansoni Cell-Surface and Secreted Antigens Does Not Identify Any Strongly Protective Vaccine Candidates in a Mouse Model of Infection. Wellcome Open Res. 2019, 4, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Conventional Techniques | Mode of Action | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stool and urine examination | Detection of parasite eggs in stool or urine samples using microscopy | Direct evidence of infection Low operational cost and feasible in low-resource settings | Low sensitivity in low-intensity infections Requires multiple samples for increased accuracy | [64,65] |

| Rectal biopsy | Microscopic examination of rectal tissue for parasite eggs | Higher sensitivity than stool examination in low-intensity infections | Invasive procedure Not practical for large-scale screening | [64,66] |

| Serological diagnosis: immunoenzymatic assays (ELISA) | Detection of antibodies or antigens in blood samples | High sensitivity and specificity, especially with modified ELISA techniques; useful in low-transmission areas | Cannot distinguish between past and current infections; potential for false positives due to cross-reactivity | [65] |

| Serological diagnosis: CCA test | Detection of CCA in serum using monoclonal antibodies | High specificity and sensitivity for active infections; useful for monitoring treatment efficacy | Limited availability and higher cost | [67] |

| Imaging techniques: ultrasound | Imaging of affected organs to assess schistosomiasis-related pathology | Non-invasive and provides real-time results; portable and cost-effective compared to other imaging methods | Requires trained personnel; less effective in detecting early-stage infections | [68,69] |

| Imaging techniques: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | Detailed imaging of internal organs to detect schistosomiasis complications | High accuracy in detecting ectopic forms of the disease; better tissue differentiation with MRI | High cost and limited accessibility; requires specialized equipment and personnel | [68] |

| Hematuria detection (reagent strips and visual examination) | Detection of blood in urine as an indicator of S. haematobium infection | Simple and cost-effective for field use; it can be performed with minimal training | Less specific, as hematuria can result from other conditions; lower sensitivity compared to imaging | [70] |

| Technique | Principle | Type of Sample Analyzed | Advantages | Disadvantages | Field or Laboratory Use | Sensitivity | Specificity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopic (conventional) | Direct observation of parasite eggs | Stool (S), urine (U) | Inexpensive, requires minimal equipment | Time-consuming, low sensitivity for early/minute infections | Laboratory (Lab) | Low (L) (especially in early stages) | High (H) (when parasite eggs are present) | [71] |

| PCR | Amplifies and detects parasite DNA | Blood (B), U, S, | Highly sensitive, can detect low levels of parasite DNA | Expensive, requires technical expertise | Lab | H | H | [73] |

| LAMP | Amplifies parasite DNA using isothermal conditions | B, U, S | Rapid, does not require a thermal cycler | Requires trained personnel, potential false positives | Both | H | H | [74] |

| RPA | Amplifies parasite DNA | B, U, S | Fast, field-deployable, does not require complex instruments | Moderate cost, less validation in field conditions | Both | H | H | [75] |

| Rapid diagnostic test | Detects antibodies or antigens using immunochromatography | B, U | Simple, rapid, field-deployable | Limited sensitivity and specificity in early infection stages | Field | M | M | |

| Lateral flow assay | Detects antigens using antibody-labeled particles | B, U | Simple, rapid, portable, field-friendly | Limited sensitivity and specificity | Field | M | M | [76] |

| Smartphone-based devices | Uses smartphone technology to analyze results from lateral flow assays | B, U | Portable, easy to use, field-deployable | Limited validation and availability | Field | M to H (depends on device) | M | [76] |

| ELISA | Detects host immune response proteins (antibodies, cytokines, etc.) | B | Can assess host immune response, widely used | Requires laboratory setup, moderate sensitivity | Lab | M | M | [77] |

| Mass spectroscopy | Detects specific proteins or biomarkers | B, tissue (T) | Highly sensitive, can identify proteins | Expensive, requires complex instruments | Lab | H | H | [78] |

| Proteomic techniques | Detects schistosome proteins (e.g., SjTs4, MF3, SjPGM, SjRAD23) | B, U | Can differentiate between current and past infections | Expensive, requires high technical expertise | Lab | H | H | [3] |

| MicroRNA detection | Detects schistosomes-specific microRNAs | B, U, S | High sensitivity | Expensive, requires field validation | Lab | H | H | [72] |

| Schistosoma Type | Genetic Target Amplified (DNA/RNA) | Amplification Method | Nature of Sample Utilized for Evaluation | Sensitivity/Specificity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. japonicum | Retrotransposon SjR2 | Conventional PCR (C-PCR) | Stool Sera/stool | [88] | |

| Nested-PCR (N-PCR) | Sera | ||||

| Retrotransposon SjR2 | LAMP | Sera | Sensitivity: 95.5% | [89] | |

| RTPCR | Feces | [90] | |||

| RT-PCR | Goat’s Plasma/serum | Sensitivity: 98.74–100% | [91] | ||

| 231-bp DNA of retrotransposon SjR2 | N-PCR | Animals (goat, buffaloes) sera and dry blood filter paper | Sensitivity: 92–100% Specificity: 97.60% | [92] | |

| Retrotransposons SjCHGCS 19 gene | N-PCR | Serum | [93] | ||

| 28S rDNA | C-PCR | Urine | [94] | ||

| 28S rDNA | LAMP | Snail (DNA) | 100 fg | [95] | |

| 28S rDNA | Feces/Urine | [96] | |||

| Cytochrome oxidase (Cox1) gene | C-PCR | Sera/urine/saliva | [97] | ||

| Cox2 | RT-PCR | Stool | [91] | ||

| Specific regions between NADH dehydrogenase (nad6) and cox2 | Multiplex real-time PCR | Stool | [98] | ||

| Specific regions between nad1 and nad2 | M-PCR | Stool | [99] | ||

| Nad1 | C-PCR RT-PCR | Feces | [100] | ||

| Nad6 | RT-PCR | Feces | [101] | ||

| miR-3479, miR-3096, miR-001, miR-277, Bantam | RT-PCR | Plasma/sera | [102] | ||

| miR223 | RT-PCR | Serum | [103] | ||

| NADH I (mitochondrial DNA) | RT-PCR | Feces | 1 EPG | [104] | |

| 18S rDNA | RT-PCR | Mouse feces and serum | 10 fg | [105] | |

| S. haematobium | Dra 1 repeats | RT- PCR | Urine | Sensitivity: ~80% | [106] |

| Dra I (DQ157698) | PCR | 1 ng | [107] | ||

| Cox1 | C-PCR | Sera/urine/saliva/semen | [108] | ||

| RT-PCR | Lavage fluid of the vagina | [108] | |||

| M-PCR | Stool | [109] | |||

| Internal transcribed spacer rDNA ITS | C-PCR | Urine | [110] | ||

| ITS2 rDNA region | RT-PCR | Urine | [84] | ||

| NADH-3 (mitochondrial DNA) | PCR | Urine | 1 pg | [111] | |

| S. mansoni | 121-bp tandem repeat sequence | C-PCR | Sera | [108] | |

| Stool | [112] | ||||

| Urine | [112] | ||||

| Touch down PCR | Serum | [113] | |||

| RT-PCR | Serum | [114] | |||

| Cerebrospinal fluid | [115] | ||||

| 28S rDNA | PCR-ELISA | Feces | [108] | ||

| 28S rDNA | Multiplex PCR | Mice urine | Sensitive: 94.4% Specificity: 99.9% | [116] | |

| C-PCR | Urine | 10 copies/μL of S. haematobium | [117] | ||

| 18S rDNA | Nested PCR | (Snail’s DNA) | 10 fg | [118] | |

| 18S rDNA | PCR | 40 pg/μL Sensitivity: 94.4% Specificity: 99.9% | [119] | ||

| Cox1 | M-PCR | Feces | [109] | ||

| Nad1 | RT-PCR | Feces | [108] | ||

| NADH dehydrogenase (nad5) | M-PCR | Feces | [108] | ||

| Specific regions between nad6 and cox2 | M-PCR | Stool | [120] | ||

| Mitochondrial minisatellite DNA sequence (620 bp) | LAMP | Feces | [84] |

| Antigen/Antibody Detection-Based Test | Test Used | Target and Species | Sensitivity | Specificity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AgD | POC-CCA | CCAs S. mansoni S. haematobium S. japonicum | 29–99% for different species | 35–95% | [124] |

| AbD soluble egg antigen (SEA) | DDIA | Anti-SEA Abs S. japonicum | 90.4–95.3 | 45.9–62% | [125] |

| AbD (purified extracts) | Schistosoma ICT IgG–IgM | Abs against partially purified Ag isolated from crude lysates of S. mansoni S. haematobium S. mekongi S. intercalatum/guineensis | 94–100 | 62–63.9 | [126] |

| AgD | Urine CCA (Schisto) Eco Teste® (POC-ECO) | CCAs S. mansoni | 90.8 | 87.9 | [127] |

| AbD (crude extracts) | Sj-ICT | Anti-AWSE Abs S. japonicum | 90.8 | 87.9 | [128] |

| AgD | UCP-LF-CAA | CAA S. haematobium S. mansoni | 80–97% | 90–100 | [129] |

| AbD (crude extracts) | Smk-ICT | Anti-AWSE Abs S. mekongi | 78.6 | 97.6 | [130] |

| AbD (SjSAP4 recombinant protein) | GICA | Abs against SjSAP4 S. japonicum | 83.3–95 | 100 | [131] |

| AbD (SEA) | Dipstick with Latex Immunochromatographic Assay (DLIA) | Anti-SEA Abs S. japonicum | 95.1 | 94.91 | [131] |

| AbD (purified extracts) | GICA | Abs against partially purified SEA (>10 kDa fragments) S. japonicum | 93.7 | 97.6 | [132] |

| AbD (recombinant proteins) | POC-ICTs | Abs against Sh-TSP-2 and MS3_01370 S. haematobium | 75–89 | 100 | [133] |

| Treatment | Category | Species Targeted | Efficacy/Details | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PZQ | Standard drug | Most Schistosoma spp. | High efficacy with 40 mg/kg, CR: 57–88%, egg reduction rates: 95% | [138] |

| PZQ (60 mg/kg) | Standard drug | S. japonicum, S. mekongi | Higher dosages for these species | [138] |

| PZQ + antimalarial artemisinin | Drug Combination | Immature larval forms of schistosomes | Higher efficacy and cure rates than PZQ alone | [141,155] |

| PZQ + Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine (DHP) | Drug Combination | Not specified | Superior effectiveness, higher systemic PZQ exposure | [141,143,155] |

| Linalool or Cinnamomum camphora extracts | Snail management (Preventive) | Snail hosts for schistosomes (S. japonicum) | Disintegration of snail gills and cell degradation, used for S. japonicum | [144] |

| PZQ + Moxidectin | Drug combination | S. mansoni and S. haematobium | CR: 92.9% (S. mansoni), 100% (S. haematobium), >99% egg reduction. PZQ damages the worm’s tegument; moxidectin affects the nervous system | [135] |

| Artesunate-PZQ | Drug combination | S. mansoni | Promising results | [147] |

| Artesunate-Mefloquine | Drug combination | S. haematobium | Effective treatment | [148] |

| PZQ (intradermal administration) | Alternative delivery | Not specified | Good tolerability, potential for improved adherence | [149] |

| LAI PZQ formulations | Alternative delivery | Not specified | Potential to simplify treatment regimens, improve adherence | [149] |

| LAI (PZQ implants) | Alternative delivery | S. japonicum | Stable plasma concentrations maintained for up to 70 days, preventing infection in mice | [151] |

| Single vs. multiple doses of PZQ | Optimized existing regimen | Different Schistosoma species | Enhanced outcomes, especially in preschool-aged children | [152] |

| Next-generation PZQ derivatives | PZQ derivatives | Various Schistosoma spp. | Improved efficacy and longer-lasting effects | [154] |

| Water Sanitation and Hygiene Programs (WASH) | Integrated with Drug Treatment | General schistosomiasis prevention | Timing and integration with sanitation efforts being explored | [153] |

| PZQ in Cohort Study | Evaluated Effect on LGIM | S. mansoni | Partial improvement in LGIM abnormalities 6 months after treatment | [145] |

| Health education programs | Complementary strategy | Essential for promoting early diagnosis, treatment adherence, and understanding of drug combinations, sanitation, and hygiene |

| Vaccine Candidate | Species Targeted | Target Antigen | Clinical Trial Phase | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r Sm-14/GLA-SE (r = recombinant) | S. mansoni | Glutathione S-transferase (GST) from S. mansoni | Phases I and IIa are complete. Phase IIb started. | [156] |

| rSh28GST/Alhydrogel® (Bilharvax) | S. haematobium | Glutathione S-transferase (GST) from S. haematobium | Phases I, II, and III ended. | [159] |

| r Sm-p80/GLA-SE | S. mansoni | Sm-p80 antigen (large subunit of calpain) | Phase I started. Evaluation for safety and immunogenicity. | [156] |

| rSm-TSP-2/Alhydrogel® | S. mansoni | Sm-TSP-2 antigen | Phase Ia finished. Phase Ib started. Safety and efficacy in human subjects are evaluated. | [162] |

| Multi-epitope peptide-based vaccine | S. mansoni | Transmembrane proteins of S. mansoni | Preclinical. | [173] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatterji, T.; Khanna, N.; Alghamdi, S.; Bhagat, T.; Gupta, N.; Alkurbi, M.O.; Sen, M.; Alghamdi, S.M.; Bamagous, G.A.; Sahoo, D.K.; et al. A Recent Advance in the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Vaccine Development for Human Schistosomiasis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9100243

Chatterji T, Khanna N, Alghamdi S, Bhagat T, Gupta N, Alkurbi MO, Sen M, Alghamdi SM, Bamagous GA, Sahoo DK, et al. A Recent Advance in the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Vaccine Development for Human Schistosomiasis. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2024; 9(10):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9100243

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatterji, Tanushri, Namrata Khanna, Saad Alghamdi, Tanya Bhagat, Nishant Gupta, Mohammad Othman Alkurbi, Manodeep Sen, Saeed Mardy Alghamdi, Ghazi A. Bamagous, Dipak Kumar Sahoo, and et al. 2024. "A Recent Advance in the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Vaccine Development for Human Schistosomiasis" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 9, no. 10: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9100243

APA StyleChatterji, T., Khanna, N., Alghamdi, S., Bhagat, T., Gupta, N., Alkurbi, M. O., Sen, M., Alghamdi, S. M., Bamagous, G. A., Sahoo, D. K., Patel, A., Kumar, P., & Yadav, V. K. (2024). A Recent Advance in the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Vaccine Development for Human Schistosomiasis. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 9(10), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9100243