Alternative Non-Drug Treatment Options of the Most Neglected Parasitic Disease Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Drug | Mode of Usage | Mode of Action | Mild to Moderate Adverse Effects | Toxicities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sodium stibogluconate | Intralesional (IL) for CL, parenteral for visceral leishmaniasis (VL) | Inhibit the parasite’s glycolysis and fatty acids β-oxidation | Abdominal pain, nausea, and erythema | Hepatic, pancreatic, renal, and cardiotoxicities, thrombocytopenia, or leukopenia | [9] |

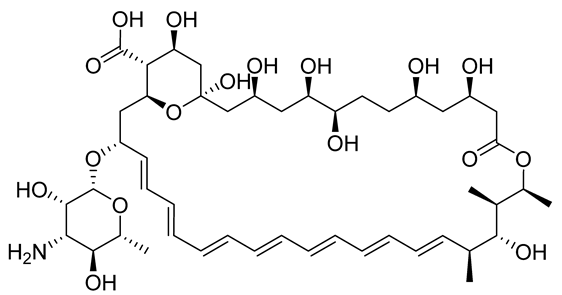

Amphotericin B | Liposomal formulations, Deoxycholate formulations | Binds the membrane sterols of the parasite and alters its permeability to K+ and Mg2+, selectively | Fever, nausea, hypokalaemia, and anorexia | Renal failure, leukopenia, cardiopathy, and hypokalaemia | [10] |

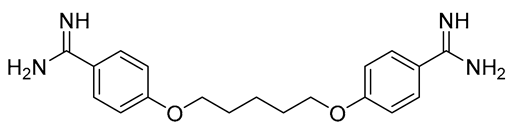

Pentamidine | Parenteral (I.M.), | Interferes with DNA synthesis and modifies the morphology of kinetoplast | Pain, headaches, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, temporary hyperglycemia, and dizziness | Hypertension, electrocardiographic alterations, tachycardia, and hypotension | [11] |

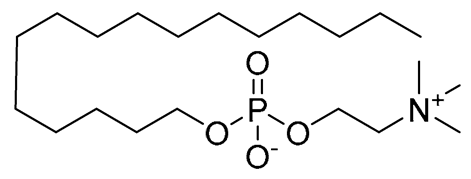

Miltefosine | Oral for VL | Associated with leishmanial alkyl-lipid metabolism and phospholipid biosynthesis | Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea | Elevated creatinine, the toxicity of the kidneys and liver, and teratogenicity | [12] |

Paromomycin | Topical for CL Parenteral for VL | Inhibits the protein biosynthesis in sensitive Leishmania parasite | Erythema, pain, and allergic contact dermatitis [13] | Liver toxicity, internal ear damage, erythema, discomfort, edema, and renal toxicity | [13] |

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Limitations

2.3. Statement of Ethics Compliance

3. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Non-Drug Treatment Options

3.1. Cryotherapy

3.2. Photodynamic Therapy

| The Parasite | The Treatment Protocol | Weeks to Achieve the Best Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. (L) major | PDT with topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid (5-ALA) and red light at 633 nm (100 joule/cm2 (J/cm2), 4 sessions). | A total of 4 weeks until achieving a complete response in 93.5% of lesions. | [31] |

| L. (L) major | PDT with topical 5-ALA and red light, (570–670 nm), (100 J/cm2, 4 sessions). | Four weeks until achieving a complete cure. | [32] |

| L. (L) major and L. (L) tropica | Solar photoprotector (SFP) and daylight-activated PDT with topical MAL. Exposure to daylight for 2.5 h (dose was not determined, <8 sessions). | Complete cure in 89%. | [33] |

| L. (L) major | PDT with 5-ALA and red light, (37 J/cm2, 24 sessions). | Twelve weeks until achieving complete healing. | [34] |

| L. (L) tropica | PDT with 5-ALA and red light, 633 nm (75 J/cm2, 3 sessions). | Eighteen weeks until achieving a complete cure. Complete resolution after the third session. | [35] |

| L. (L) tropica | PDT with topical MAL and red light, 635 nm (100 J/cm2, 3 sessions). | Six weeks until achieving a complete response. | [36] |

| L. (L) tropica | PDT with 5-ALA and red light, 630 nm (37 J/cm2, 5 sessions). | Five weeks until achieving a complete recovery. | [37] |

| L. (L.) tropica | PDT with MAL and red light, 630 nm (dose was not determined, 8 sessions). | Seven weeks until achieving a complete cure. | [38] |

3.3. Thermotherapy

3.3.1. Hot Water Baths

3.3.2. Laser Therapy

3.3.3. Ultrasound Therapy

3.3.4. Infrared and Microwave

3.3.5. Handheld Exothermic Crystallization Thermotherapy

3.3.6. Radiofrequency

3.4. Traditional Non-Drug Therapy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dujardin, J.C.; Campino, L.; Cañavate, C.; Dedet, J.P.; Gradoni, L.; Soteriadou, K.; Mazeris, A.; Ozbel, Y.; Boelaert, M. Spread of vector-borne diseases and neglect of Leishmaniasis, Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 4, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, O.P.; Hasker, E.; Boelaert, M.; Sundar, S. Elimination of visceral leishmaniasis on the Indian subcontinent. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, e304–e309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevric, I.; Cappel, M.A.; Keeling, J.H. New world and Old World Leishmania infections: A practical review. Dermatol. Clin. 2015, 33, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlagh, A.; Salehzadeh, A.; Zahirnia, A.H.; Davari, B. 10-year trends in epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Hamadan Province, West of Iran (2007–2016). Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzaro, G.; Rovaris, M.; Veraldi, S. Leishmaniasis: A disease with many names. JAMA Dermatol. 2014, 150, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, C.V.; Craft, N. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Dermatol. Ther. 2009, 22, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abpeikar, Z.; Safaei, M.; Alizadeh, A.A.; Goodarzi, A.; Hatam, G. The novel treatments based on tissue engineering, cell therapy and nanotechnology for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 633, 122615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, E.; Price, H.P.; Hoskins, C. Current and future strategies against cutaneous parasites. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, J.; Alvar, J.; Mullen, A.B.; Carter, K.C.; Rodríguez, C.; San Andrés, M.I.; San Andrés, M.D.; Baillie, A.J.; González, F. Pharmacokinetics, toxicities, and efficacies of sodium stibogluconate formulations after intravenous administration in animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2781–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamill, R.J. Amphotericin B formulations: A comparative review of efficacy and toxicity. Drugs 2013, 73, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, M.; Kron, M.A.; Brown, R.B. Pentamidine: A review. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1985, 7, 625–6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.; Arana, B.A.; Toledo, J.; Rizzo, N.; Vega, J.C.; Diaz, A.; Luz, M.; Gutierrez, P.; Arboleda, M.; Berman, J.D.; et al. Miltefosine for NW cutaneous leishmaniasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veraldi, S.; Benzecry, V.; Faraci, A.G.; Nazzaro, G. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by paromomycin. Contact Dermat. 2019, 81, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Khandpur, S. Guidelines for cryotherapy. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2009, 75, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Garza-Tovar, T.F.; Sacriste-Hernández, M.I.; Juárez-Durán, E.R.; Arenas, R. An overview of the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Fac. Rev. 2020, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Mohammad, S.; Hak, A.; Pogu, S.V.; Rengan, A.K. Radiotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and cryoablation-induced abscopal effect: Challenges and future prospects. Cancer Innov. 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosleh, I.M.; Geith, E.; Natsheh, L.; Schönian, G.; Abotteen, N.; Kharabsheh, S.A. Efficacy of a weekly cryotherapy regimen to treat Leishmania major cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008, 58, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asilian, A.; Sadeghinia, A.; Faghihi, G.; Momeni, A. Comparative study of the efficacy of combined cryotherapy and intralesional meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) vs. cryotherapy and intralesional meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) alone for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2004, 43, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.; Rojas, E.; Guzman, M.; Verduguez, A.; Nena, W.; Maldonado, M.; Cruz, M.; Gracia, L.; Villarroel, D.; Alavi, I.; et al. Intralesional antimony for single lesions of bolivian cutaneous leishmaniasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Negera, E.; Gadisa, E.; Hussein, J.; Engers, H.; Kuru, T.; Gedamu, L.; Aseffa, A. Treatment response of cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania aethiopica to cryotherapy and generic sodium stibogluconate from patients in Silti, Ethiopia. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 106, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranawaka, R.R.; Weerakoon, H.S.; Opathella, N. Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy on Leishmania donovani cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2011, 22, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, H.J.; Reedijk, S.H.; Schallig, H.D. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: Recent developments in diagnosis and management. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2015, 16, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Carvajal, L.; Cardona-Arias, J.A.; Zapata-Cardona, M.I.; Sánchez-Giraldo, V.; Vélez, I.D. Efficacy of cryotherapy for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis: Meta-analyses of clinical trials. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, S.; Schwartz, R.A.; Patil, A.; Grabbe, S.; Goldust, M. Treatment options for leishmaniasis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roatt, B.M.; de Oliveira Cardoso, J.M.; De Brito, R.C.F.; Coura-Vital, W.; de Oliveira Aguiar-Soares, R.D.; Reis, A.B. Recent advances and new strategies on leishmaniasis treatment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8965–8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Snoek, E.M.; Robinson, D.J.; Van Hellemond, J.J.; Neumann, H.A.M. A review of photodynamic therapy in cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2008, 22, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akilov, O.E.; Kosaka, S.; O’Riordan, K.; Hasan, T. Parasiticidal effect of δ-aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis is indirect and mediated through the killing of the host cells. Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 16, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzavara-Pinton, P.G.; Venturini, M.; Sala, R. Photodynamic therapy: Update 2006 Part 1: Photochemistry and photobiology. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2007, 21, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Viana, S.M.; Ng, D.K.; Kolli, B.K.; Chang, K.P.; de Oliveira, C.I. Photodynamic inactivation of Leishmania braziliensis doubly sensitized with uroporphyrin and diamino-phthalocyanine activates effector functions of macrophages in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozlem-Caliskan, S.; Ilikci-Sagkan, R.; Karakas, H.; Sever, S.; Yildirim, C.; Balikci, M.; Ertabaklar, H. Efficacy of malachite green mediated photodynamic therapy on treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: In vitro study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2022, 40, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asilian, A.; Davami, M. Comparison between the efficacy of photodynamic therapy and topical paromomycin in the treatment of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis: A placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2006, 31, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffarifar, F.; Jorjani, O.; Mirshams, M.; Miranbaygi, M.H.; Hosseini, Z.K. Photodynamic therapy as a new treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. East Mediterr Health J. 2006, 12, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Enk, C.D.; Fritsch, C.; Jonas, F.; Nasereddin, A.; Ingber, A.; Jaffe, C.L.; Ruzicka, T. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis with photodynamic therapy. Arch. Dermatol. 2003, 139, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, M.B.; Jemec, G.B.; Fabricius, S. Effective treatment with photodynamic therapy of cutaneous leishmaniasis: A case report. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, H.; Kohen, S.; Taxy, J.; Libman, M.; Cibull, T.; Billick, K. Leishmania tropica infection of the ear treated with photodynamic therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2020, 6, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohl, S.; Kauer, F.; Paasch, U.; Simon, J.C. Photodynamic treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2007, 5, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, C.; Toberer, F.; Enk, A.; Gholam, P. Effective treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica with topical photodynamic therapy. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2016, 14, 836–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slape, D.R.M.; Kim, E.N.Y.; Weller, P.; Gupta, M. Leishmania tropica successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Aust. J. Dermatol. 2019, 60, e64–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazgarnia, A.; Taheri, A.R.; Soudmand, S.; Parizi, A.J.; Rajabi, O.; Darbandi, M.S. Antiparasitic effects of gold nanoparticles with microwave radiation on promastigotes and amastigotes of Leishmania major. Int. J. Hyperthermia. 2013, 29, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasak Guner, R.; Berksoy Hayta, S.; Tosun, M.; Akyol, M.; Ozpınar, N.; Akın Polat, Z.; Egilmez, R.; Celikgün, S.; Cam, S. Combination of infra-red light with nanogold targeting macrophages in the treatment of Leishmania major infected BALB/C mice. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2022, 41, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neva, F.A.; Petersen, E.A.; Corsey, R.; Bogaert, H.; Martinez, D. Observations on local heat treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am. J. Trop Med. Hyg. 1984, 33, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnett, A.; Nguyen, T.A.; Cannavino, C.; Krakowski, A.C. Ablative fractional laser resurfacing with topical paromomycin as adjunctive treatment for a recalcitrant cutaneous leishmaniasis wound. Lasers. Surg. Med. 2015, 47, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, G.; Sannino, M.; Caterino, P.; Cannarozzo, G.; Bennardo, L.; Nisticò, S.P. Fractional CO2 laser-assisted topical rifamycin drug delivery in the treatment of pediatric cutaneous leishmaniasis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2021, 38, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilerowicz, Y.; Koren, A.; Mashiah, J.; Katz, O.; Sprecher, E.; Artzi, O. Fractional ablative carbon dioxide laser followed by topical sodium stibogluconate application: A treatment option for pediatric cutaneous leishmaniasis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2018, 35, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artzi, O.; Sprecher, E.; Koren, A.; Mehrabi, J.N.; Katz, O.; Hilerowich, Y. fractional ablative co2 laser followed by topical application of sodium stibogluconate for treatment of active cutaneous leishmaniasis: A randomized controlled trial. Acta. Derm. Venereol. 2019, 99, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffary, F.; Nilforoushzadeh, M.A.; Siadat, A.; Haftbaradaran, E.; Ansari, N.; Ahmadi, E. A comparison between the effects of glucantime, topical trichloroacetic acid 50% plus glucantime, and fractional carbon dioxide laser plus glucantime on cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2016, 2016, 6462804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radmanesh, M.; Omidian, E. The pulsed dye laser is more effective and rapidly acting than intralesional meglumine antimoniate therapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2017, 28, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaie, M.L.; Ibrahim, S.M. The effect of pulsed dye laser on cutaneous leishmaniasis and its impact on the dermatology life quality index. J. Cosmet. Laser. Ther. 2018, 20, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaoui, W.; Chiheb, S.; Benchikhi, H. Efficacy of pulsed-dye laser on residual red lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis Efficacité du laser à colorant pulsé sur les lésions résiduelles rouges de la leishmaniose cutanée. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 142, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babajev, K.B.; Babajev, O.G.; Korepanov, V.I. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis using a carbon dioxide laser. Bull World Health Organ. 1991, 69, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asilian, A.; Sharif, A.; Faghihi, G.; Enshaeieh, S.H.; Shariati, F.; Siadat, A.H. Evaluation of CO2 laser efficacy in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2004, 43, 736–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asilian, A.; Iraji, F.; Hedaiti, H.R.; Siadat, A.H.; Enshaieh, S. Carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of lupoid cutaneous leishmaniasis (LCL): A case series of 24 patients. Dermatol. Online J. 2006, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi Meymandi, S.; Zandi, S.; Aghaie, H.; Heshmatkhah, A. Efficacy of CO2 laser for treatment of anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis, compared with combination of cryotherapy and intralesional meglumine antimoniate. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2011, 25, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi Goyonlo, V.; Karrabi, M.; Kiafar, B. Efficacy of erbium glass laser in the treatment of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis: A case series. Aust. J. Dermatol. 2019, 60, e29–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, M.; Jadbabaei, M.; Omidian, E.; Omidian, Z. The effect of Nd: YAG laser therapy on cutaneous leishmaniasis compared to intralesional meglumine antimoniate. Postepy. Dermatol. Alergol. 2019, 36, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Muslet, N.A.; Khalid, A.I. Clinical evaluation of low level laser therapy in treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Our. Dermatol. Online 2012, 3, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Khan, A.U.; Ullah, A.; Khan, M.; Ahmad, I. Low-level laser therapy for the treatment of early stage cutaneous leishmaniasis: A pilot study. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxmudov, F.A.; Raxmatov, O.B.; Latipov, I.I.; Rustamov, M.K.; Sharapova, G.S. Intravenous laser blood irradiation in the complex treatment of patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Hunan Univ. Nat. Sci. 2021, 48, 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Maxmudov, F.A. The Role of Intravenous Laser Blood Irradiation in the Therapy of Patients with Skin Leishmaniasis. Cent. Asian J. Med. Nat. Sci. 2022, 3, 587–591. [Google Scholar]

- Omi, T.; Kawana, S.; Sato, S.; Takezaki, S.; Honda, M.; Igarashi, T.; Hankins, R.W.; Bjerring, P.; Thestrup-Pedersen, K. Cutaneous immunological activation elicited by a low-fluence pulsed dye laser. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005, 153, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jeboory, S.R.; Jassim, A.S.; Al-Ani, R.R. The effect of He: Ne laser on viability and growth rate of Leishmania major. Iraqi. J. Laser. 2007, 6, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sabaa, H.S.; Zghair, K.H.; Mohammed, N.R.; Musa, I.S.; Abd, R.S. The effect of Nd: YAG lasers on Leishmania donovani promastigotes. World J. Exp. Biosci. 2016, 4, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Aram, H.; Leibovici, V. Ultrasound-induced hyperthermia in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Cutis 1987, 40, 350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar, A.; Junaid, N. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis with infrared heat. Int. J. Dermatol. 1986, 25, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskandari, S.E.; Azimzadeh, A.; Bahar, M.; Naraghi, Z.S.; Javadi, A.; Khamesipour, A.; Mohamadi, A.M. Efficacy of microwave and infrared radiation in the treatment of the skin lesions caused by leishmania major in an animal model. Iran J Public Health. 2012, 41, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mashayekhi Goyonlo, V.; Hassan Abadi, H.; Zandi, H.; Jamali, J.; Nahidi, Y.; Taheri, A.R.; Kiafar, B. Efficacy of infrared thermotherapy for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis: A descriptive study of 39 cases in Mashhad, Iran. Iran. J. Dermatol. 2021, 24, e0122569. [Google Scholar]

- Sharquie, K.E.; Al-Mashhadani, S.A.; Noaimi, A.A.; Al-Zoubaidi, W.B. Microwave Thermotherapy: New treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Our Dermatol. Online 2015, 6, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.; Memon, A.A.; Baqi, S.; Witzig, R. Low-cost thermotherapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sindh, Pakistan. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2014, 64, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, B.M.; Miller, D.; Witzig, R.S.; Boggild, A.K.; Llanos-Cuentas, A. Novel low-cost thermotherapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis in Peru. PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 2013, 7, e2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.; Liyanage, A.; Deerasinghe, T.; Sumanasena, B.; Munidasa, D.; de Silva, H.; Weerasingha, S.; Fernandopulle, R.; Karunaweera, N. Therapeutic response to thermotherapy in cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment failures for sodium stibogluconate: A randomized controlled proof of principle clinical trial. Am. J. Trop Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämink, S.; Abdi, A.; Kamau, C.; Ashraf, S.; Ansari, M.A.; Qureshi, N.A.; Schallig, H.; Grobusch, M.P.; Fernhout, J.; Ritmeijer, K. Failure of an innovative low-cost, noninvasive thermotherapy device for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica in Pakistan. Am. J. Trop Med. Hyg. 2019, 101, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navin, T.R.; Arana, B.A.; Arana, F.E.; de Mérida, A.M.; Castillo, A.L.; Pozuelos, J.L. Placebo-controlled clinical trial of meglumine antimonate (glucantime) vs. localized controlled heat in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Guatemala. Am. J. Trop Med. Hyg. 1990, 42, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Castrejon, O.; Walton, B.C.; Rivas-Sanchez, B.; Garcia, M.E.; Lazaro, G.J.; Hobart, O.; Roldan, S.; Floriani-Verdugo, J.; Munguia-Saldana, A.; Berzaluce, R. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis with localized current field. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1997, 57, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siadat, A.H.; Iraji, F.; Zolfaghari, A.; Shariat, S.; Jazi, S.B. Heat therapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis: A literature review. J Res Med. Sci. 2021, 26, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghian, G.; Nilfroushzadeh, M.A.; Iraji, F. Efficacy of local heat therapy by radiofrequency in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, compared with intralesional injection of meglumine antimoniate. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 32, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumb, R.A.; Prasad, N.; Khandelwal, K.; Aara, N.; Mehta, R.D.; Ghiya, B.C.; Salotra, P.; Wei, L.; Peters, S.; Satoskar, A.R. Long-term efficacy of single-dose radiofrequency-induced heat therapy vs. intralesional antimonials for cutaneous leishmaniasis in India. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 168, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, J.C.; Sanchez, B.F.; Montero, L.M.; Montaña, R.; del Pilar Mahecha, M.; Dueñes, B.; Baron, Á.R.; Reithinger, R. The efficacy of thermotherapy to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis in Colombia: A comparative observational study in an operational setting. Trans. R Soc. Trop Med. Hyg. 2009, 103, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refai, W.F.; Madarasingha, N.P.; Sumanasena, B.; Weerasingha, S.; De Silva, A.; Fernandopulle, R.; Satoskar, A.R.; Karunaweera, N.D. Efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of thermotherapy in the treatment of Leishmania donovani–induced cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Am. J. Trop Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reithinger, R.; Mohsen, M.; Wahid, M.; Bismullah, M.; Quinnell, R.J.; Davies, C.R.; Kolaczinski, J.; David, J.R. Efficacy of thermotherapy to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica in Kabul, Afghanistan: A randomized, controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 1148–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.; Cruz, C.; Godoy, G.; Robledo, S.M.; Vélez, I.D. Thermoterapy effective and safer than miltefosine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Colombia. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop Sao. Paulo. 2013, 55, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, S.V.C.B.; Costa, C.H.N. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis with thermotherapy in Brazil: An efficacy and safety study. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2018, 93, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronson, N.E.; Wortmann, G.W.; Byrne, W.R.; Howard, R.S.; Bernstein, W.B.; Marovich, M.A.; Polhemus, M.E.; Yoon, I.K.; Hummer, K.A.; Gasser, R.A., Jr.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of local heat therapy versus intravenous sodium stibogluconate for the treatment of cutaneous Leishmania major infection. PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 2010, 4, e628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumb, R.A.; Satoskar, A.R. Radiofrequency-induced heat therapy as first-line treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2011, 9, 623–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sig, A.K.; Guney, M.; Guclu, A.U.; Ozmen, E. Medicinal leech therapy—An overall perspective. Integr. Med. Res. 2017, 6, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarshenas, M. Leech therapy in treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis: A case report. J. Integr. Med. Engl. Ed. 2017, 15, 407–410. [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi, M.M.; Zare, F.; Handjani, F.; Nimrouzi, M.; Zarshenas, M.M. Overview of herbal and traditional remedies in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis based on Traditional Persian Medicine. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, H.C.; Ahmadi, F.; Schleicher, U.; Sauerborn, R.; Bermejo, J.L.; Amirih, M.L.; Sakhayee, I.; Bogdan, C.; Stahl, K.W. A randomized controlled phase IIb wound healing trial of cutaneous leishmaniasis ulcers with 0.045% pharmaceutical chlorite (DAC N-055) with and without bipolar high frequency electro-cauterization versus intralesional antimony in Afghanistan. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebran, A.F.; Schleicher, U.; Steiner, R.; Wentker, P.; Mahfuz, F.; Stahl, H.C.; Amin, F.M.; Bogdan, C.; Stahl, K.W. Rapid healing of cutaneous leishmaniasis by high-frequency electrocauterization and hydrogel wound care with or without DAC N-055: A randomized controlled phase IIa trial in Kabul. PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 2014, 8, e2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Laser Type | Cases | Treatment Session | Achieved Outcomes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractional CO2 laser + paromomycin. | A 16-year-old female with several non-tender, non-healing CL wounds on her bilateral upper and lower extremities. | Two sessions at one-month interval. |

| [42] |

| Fractional CO2 laser, assisted by topical rifamycin. | One child. | Two sessions at one-month intervals of fractional CO2 laser, followed by topical application of rifamycin for three days. |

| [43] |

| Fractional ablative CO2 laser followed by ISSG application. | Ten children. | Patients were treated with fractional ablative carbon dioxide laser followed by immediate ISSG. |

| [44] |

| Fractional Ablative CO2 laser followed by ISSG. | A total of 20 patients/181 lesions. |

| Compared with ISSG, fractional CO2 laser treatment followed by ISSG application is less painful and produces a superior final cosmetic result. | [45] |

Comparison between the effects of:

| Ninety patients in three groups:

|

| Complete healing in:

| [46] |

| Pulsed dye laser (PDL). | A total of 17 patients with 81 lesions:

|

|

| [47] |

| A total of 25 lesions in 12 patients. |

|

| [48] | |

Three patients:

|

|

| [49] | |

| Continuous CO2 laser. |

|

|

| [50] |

| Patients were administered a local anesthetic and treated by a focused laser beam (surface power density was about 2.3–3.0 kW/cm2. Finally, the defocused laser beam is directed at the wound (laser surface power density: 200–400 W/cm2) until the entire wound surface becomes covered with a thin light-brown film. | A concentrated laser beam could vaporize individual leishmaniasis lesions. In cases of numerous lesions, the largest and most infected ulcers were removed in a single session (up to 5–6 foci), and the remaining lesions were removed as soon as the first wounds started to epithelialize. | [51] | |

| Twenty-four patients with lupoid cutaneous leishmaniasis for more than one year. |

|

| [52] | |

| CO2 laser (maximum power of 30 W and pulse duration of 0.01–1 s, and mode of a continuous wave); Cryotherapy (twice weekly) with intralesional meglumine antimoniate weekly, until complete cure or up to 12 weeks. |

| [53] | |

| Erbium glass laser. | A total of 14 patients/20 lesions. | Weekly sessions with the Palomar 1540 nm erbium glass fractional laser using a handpiece with a 10 mm spot size, four passes of 50–70 mJ/cm2 fluence, and a pulse length of 10 ms. |

| [54] |

| Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (ND/YAG) laser. | A total of 16 patients were treated simultaneously, where one lesion was treated with glucantime and another with ND/YAG laser. | Average glucantime sessions = 7.31 ± 4; Average laser therapy sessions = 2.56 ± 0. 9. | ND/YAG laser therapy for CL led to complete recovery of patients in a shorter time with fewer complications than glucantime medication. | [55] |

| Low-level laser therapy. | Thirteen patients. | A Diode laser probe with λ 820 nm was used, followed by a cluster probe. Three sessions weekly for a total of ten sessions, the dose was: I. Diode laser probe with an energy density of 48 J/cm2 30 s; II. Cluster probe with an energy density of 9.6 J/cm2 for 2 min. | A total of 92.3% of the patients who received treatment had excellent outcomes. The difficulties were minor and temporary. | [56] |

| A total of 53 patients/123 lesions. Divided into two groups:

| Four sessions at one-week intervals. |

| [57] | |

| Intravenous laser blood irradiation (ILBI). | A total of 40 patients with one or more wounds of at least 5 cm diameter and a swollen and purulent mass around the wound.

| Ten days of ILBI therapy using the Matrix-VLOK device, continuous radiation mode for 15 min, alternating VLOK radiating heads at a wavelength of 0.63 microns and radiation energies of 1.5–2.0 mV. |

| [58] |

| A total of 40 patients, each having one or more wounds that are at least 5 cm in diameter. | A total of 25 patients received intravenous laser therapy in addition to regular medical treatment for 10 days, while 15 patients received regular medical treatment alone. | It has been demonstrated that ILBI therapy is successful as a painless treatment for patients undergoing clinical and pathogenetic therapy. | [59] |

| Parasite | Patients/Groups | The RF Procedure | Results/Healing Rate | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. (V) braziliensis L. (L) mexicana |

| RF generated heat (50 °C for 30 s, 3 times at 7-day intervals). |

| [72] |

| L. (L) tropica |

| RF generated heat (50℃ surface temperature for 30 s, using a handheld RF heat generator). |

| [71] |

| L. (L) mexicana |

| Localized current field (LCF-RF) generated heat (50 °C for 30 s, one time). | A total of 90% healing rate. | [73] |

| L. (L) tropica |

| RF generated (50 °C for 30 s), using ThermoMed 1.8 RF generator). |

| [74] |

| Anthroponotic |

| RF generated heat (50° for 30 s, 4 times at 7-day interval). |

| [75] |

| Not identified |

| LCF-RF generated heat (50 °C for 30 s, one time), using a ThermoMed 1.8 LCF-RF generator. |

| [76] |

| L. (L) major |

| RF generated heat (50 °C for 30 s, one time), using ThermoMed 1.8 generator. |

| [77] |

| L. (L) tropica |

| RF generated heat (50 °C for 30 s, one time), ThermoMed 1.8 generator. |

| [76] |

| L. panamensis L. (V) braziliensis L. (L) amazonensis L. (L) mexicana L. (L) infantum |

| RF generated heat (50 °C for 30 s, one time), ThermoMed 1.8 generator. |

| [78] |

| L. (L) tropica |

| LCF-RF generated heat (50° for 30–60 s), using RF ThermoMed 1.8 generator. |

| [79] |

| L. (V) panamensis L. (V) braziliensis |

| RF generated heat (50 °C for 30 s), using ThermoMed 1.8 generator. |

| [80] |

| L. (L) donovani |

| ThermoMed Model 1·8. |

| [81] |

| Not identified |

| RF generated heat (50 °C for 30 s, one time), ThermoMed 1.8 generator. |

| [82] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orabi, M.A.A.; Lahiq, A.A.; Awadh, A.A.A.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Abdel-Wahab, B.A.; Abdel-Sattar, E.-S. Alternative Non-Drug Treatment Options of the Most Neglected Parasitic Disease Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Narrative Review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8050275

Orabi MAA, Lahiq AA, Awadh AAA, Alshahrani MM, Abdel-Wahab BA, Abdel-Sattar E-S. Alternative Non-Drug Treatment Options of the Most Neglected Parasitic Disease Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Narrative Review. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2023; 8(5):275. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8050275

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrabi, Mohamed A. A., Ahmed A. Lahiq, Ahmed Abdullah Al Awadh, Mohammed Merae Alshahrani, Basel A. Abdel-Wahab, and El-Shaymaa Abdel-Sattar. 2023. "Alternative Non-Drug Treatment Options of the Most Neglected Parasitic Disease Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Narrative Review" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 8, no. 5: 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8050275

APA StyleOrabi, M. A. A., Lahiq, A. A., Awadh, A. A. A., Alshahrani, M. M., Abdel-Wahab, B. A., & Abdel-Sattar, E.-S. (2023). Alternative Non-Drug Treatment Options of the Most Neglected Parasitic Disease Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Narrative Review. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 8(5), 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8050275