Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is included in the ten most urgent global public health threats. Global evidence suggests that antibiotics were over prescribed during the early waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Inappropriate use of antibiotics drives the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance. This study aimed to examine the impact of COVID-19 on Ni-Vanuatu health worker knowledge, beliefs, and practices (KBP) regarding antibiotic prescribing and awareness of antibacterial AMR. A mixed methods study was conducted using questionnaires and in-depth interviews in 2018 and 2022. A total of 49 respondents completed both baseline (2018) and follow-up (2022) questionnaires. Knowledge scores about prescribing improved between surveys, although health workers were less confident about some prescribing activities. Respondents identified barriers to optimal hand hygiene performance. More than three-quarters of respondents reported that COVID-19 influenced their prescribing practice and heightened their awareness of ABR: “more careful”, “more aware”, “stricter”, and “need more community awareness”. Recommendations include providing ongoing continuing professional development to improve knowledge, enhance skills, and maintain prescribing competency; formalising antibiotic stewardship and infection, prevention, and control (IPC) programmes to optimise prescribing and IPC practices; and raising community awareness about ABR to support more effective use of medications.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1], was first detected in Wuhan, China and declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the World Health Organization (WHO) in early 2020 [2]. During the initial stages of the infection, the symptoms, signs, and radiographic changes of COVID-19 overlap those of many other respiratory tract infections, making it challenging to distinguish from illness caused by other pathogens, secondary bacterial infections, or co-infections [3].

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was highlighted as a global public health threat in 2014 at the World Health Assembly (WHA) [4]. Research predicts that by 2050, AMR will be responsible for some 10 million deaths annually and cost upwards of USD 100 trillion [3]. Infection prevention and control (IPC) and antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) were identified as key strategies to address AMR in healthcare settings in objectives three and four of WHA’s Global Action Plan (GAP) to contain AMR [4]. All members of the WHA agreed to develop and implement a national action plan (NAP) based on the GAP’s five objectives. Given the constraints they face and the added burden of the pandemic, many low- and middle-income-countries (LMICs), like Vanuatu and other Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICTs), have been slower to achieve this [5].

Evidence indicates that antibiotics were over and unnecessarily prescribed during the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic [6,7,8,9]. Although this was found to be greater in some LMICs [10,11,12,13], studies on the impact of COVID-19 in LMICs are scarce. Research globally suggests that the prescribing of antibiotics may have been far higher than the prevalence of secondary bacterial infections and co-infections may have been necessitated [11,14,15,16,17]. Increased and inappropriate use of antibiotics are important drivers for the emergence and spread of AMR, including antibacterial resistance (ABR) [3,18]. Some over-prescribing may have been unavoidable during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic [19] because of substantial uncertainties about optimal clinical management, lack of treatment protocols, shortages of trained staff, supply line disruptions, and an overwhelming number of patients presenting for treatment [3]. It is likely that LMICs may have been impacted by COVID-19–associated ABR to a greater extent than HICs. In LMICs, awareness about ABR is generally lower, microbiology capacity often limited, and health systems already stretched, so the need and urgency to implement strategies to manage and contain the pandemic may have resulted in further stress to the system [3].

In 2018, development of a national antibiotic guideline commenced and was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Engaging Ni-Vanuatu health workers in guideline development is pivotal to ensuring uptake and adherence to the guideline. Gaining an understanding of the knowledge, beliefs, and practices (KBP) of Ni-Vanuatu health workers regarding antibiotic-prescribing and awareness of ABR is appropriate and timely and may provide valuable information to inform these efforts. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine health worker KBP regarding antibiotic prescribing and awareness of ABR and to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health worker KBP with respect to antibiotic prescribing and ABR.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design: Mixed Methods Sequential Explanatory Design

This study used a mixed methods design. Data collection included two components: (i) a quantitative KBP questionnaire which included both closed and open-ended questions, and (ii) face-to-face and telephone interviews. The rationale for using a mixed methods design was to provide participants with the opportunity to add clarification and explanation to the quantitative questionnaire responses [20,21].

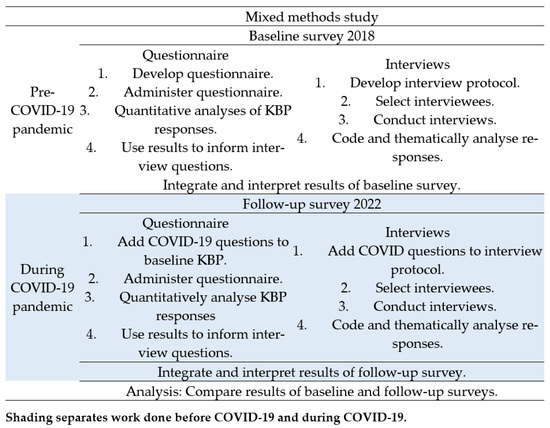

Our mixed methods approach prioritised quantitative over qualitative methodology in a sequential explanatory design [20]. We considered the research question, which method should take precedence, the order that the data collection and analysis should occur, and when the data would be combined [20,22]. More information can be found in Figure 1, which provides a visual model of the mixed methods sequential explanatory design procedures [20].

Figure 1.

Visual model of mixed methods study into the impact of COVID-19 on knowledge, beliefs, and practices (KBP) regarding antibiotic prescribing and awareness of antibiotic resistance in Vanuatu.

2.2. Study Setting

The Republic of Vanuatu is a PICT with a population of 319,000 [23]. The country is divided into two Health Directorates: (Southern and Northern), each served by a referral hospital, Vila Central Hospital (VCH) and the smaller Northern Provincial Hospital (NPH), respectively. Vanuatu’s main referral hospital, VCH, has 230 beds catering for patients in the paediatrics, medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology, mind care, tuberculosis, and surgery wards. The following outpatient services are provided: emergency; adult; paediatric; surgery; oral health; eye care; maternity and family planning; ear, nose, and throat care; and physiotherapy. There is also a medical laboratory and a radiology unit.

2.3. Quantitative Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices (KBP) Survey

Two validated questionnaires were used to develop the survey instrument: a knowledge, attitudes, and practices survey from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) [24] and the WHO infection prevention and control assessment framework [25]. After permissions were obtained to use the UNSW survey, several questions were selected and adapted for use in our survey. The remaining questions and clinical scenarios were based on the Vanuatu Health Workers Manual (VHWM) [26], the Vanuatu COVID-19 Protocol [27], and the Fiji Antibiotic Treatment Guideline [28]. The baseline KBP questionnaire consisted of 39 questions and five clinical scenarios. The tool covered four areas, including participant demographics, knowledge, and beliefs about antibiotic prescribing, ABR, and prescribing practices. Antibiotic prescribing knowledge was assessed using five clinical scenarios. Each clinical scenario included nine antibiotics and other treatment choices. In order to assess confidence in prescribing skills, health workers were presented with a list of eight statements about activities associated with prescribing antibiotics and asked to indicate their level of confidence with each. Likert scale questions were used to measure knowledge, beliefs, and awareness about ABR. Health worker’s KBPs regarding IPC were evaluated using WHO’s five hand hygiene moments and other questions and statements about IPC practice [25]. Health workers were also asked about the information sources they use to inform their prescribing decisions as well as the possible reasons why patients request antibiotics when they may not be required. The follow-up questionnaire included seven additional questions and four additional clinical scenarios relating to prescribing during the COVID-19 pandemic. The baseline questionnaire was available in print form only, whilst the follow-up questionnaire was also available online.

2.4. Validation Process

A group of health professionals, both Ni-Vanuatu and Australian, provided feedback on the questionnaire’s face-validity, and a senior Ni-Vanuatu clinician and an Australian infectious disease physician assessed the content validity. A pilot study was conducted on five Ni-Vanuatu health workers who were given both the participant information sheet (PIS) and questionnaire and invited to provide feedback. The KBP questionnaire was revised based on the feedback. The internal consistency reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha [29].

2.5. Study Participants

In 2018, healthcare workers registered with the Vanuatu Drugs and Therapeutics Committee to prescribe antibiotics and employed at Vila Central Hospital were invited to participate (an estimate of 75). Participants were able to choose how they completed the questionnaire: by face-to-face interview with a researcher, self-completion of a hard copy questionnaire, or self-completion of an online questionnaire (at follow-up only). A total of 65 healthcare workers responded to the baseline survey in 2018 and 67 to the follow-up in 2022.

All participants were invited to participate in face-to-face interviews following completion of the baseline questionnaire. Seven of the interviewees who agreed to participate in the follow-up questionnaire were invited to be re-interviewed after completing the questionnaire. These interviewees were selected by two of the authors (NDF, AM) based on their professional group representativeness and clinical experience.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Quantitative Data

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the numeric data. The paired t-test was used to compare means when the data were interval and normally distributed and the non-parametric test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test (WSRT), was used to compare ordinal data. The McNemar test for paired data was used to analyse relationships between categorical variables. The alpha level was set as 0.05 and a p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant [30]. The analysis was conducted using Stata version 15 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

2.6.2. Qualitative Data

The constant comparative method (a qualitative research technique) was employed to analyse the responses from the open-ended questions and interviews [20]. Since the purpose of the qualitative component was to expand upon the quantitative results, principal themes were identified a priori and based on the subject content of the questionnaire. Within these themes, information with similar content was grouped, reviewed, re-grouped, and refined into higher levels of sub-themes (similarity and contrast principles) using a coding scheme [20]. Selected results were presented in table form and/or integrated with the text where they supported or provided insight into the quantitative results.

2.6.3. Ethics

The study was approved by the Vanuatu Cultural Council and the Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol 2017/056). Those who elected to participate were given the participant information sheet providing details about the study, survey instruments, requirements of being a participant, confidentiality, and use of the data. Written consent was obtained from those who agreed to participate.

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire Validation

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.8566 for the KBP questions relating to health worker confidence and was 0.8739 for those relating to beliefs, suggesting both sets of questions have a high internal consistency.

3.2. Demographic and Professional Profile

Results are reported for the 49 participants (49 pairs) who completed both surveys. They comprised 22 nurses and midwives, 21 doctors and a small mixed group of two managers, two dentists, and two pharmacists. To ensure participants remained anonymous, the nurse manager was assigned to the nurses’ and midwives’ group, totalling 23, and the medical manager, dentists, and pharmacists to the doctors’ group, totalling 26. Likewise, since a few doctors were trained in China as opposed to Cuba and the number of respondents in both groups was small, the respondents were grouped together to ensure anonymity. Overall, 47% (23) of participants were female. Of the nurses’ group, 61% (14) were female and aged 45 years and older. In contrast, 65% (17) of the doctors’ group were male, and 46% (12) were aged 35 years and younger. Table 1 provides additional demographic details of the study participants who completed both baseline and follow-up surveys.

Table 1.

Demographic details at follow-up (2022) of participants who completed both baseline and follow-up surveys about the influence of COVID-19 on Ni-Vanuatu health worker’s knowledge, beliefs, and practices regarding antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance.

3.3. Knowledge about Antibiotic Prescribing and Antimicrobial Resistance

3.3.1. Clinical Scenarios

Table 2 provides the number and proportion of respondents who selected correct treatments for each of the five clinical scenarios listed on the KBP questionnaire. Table S1 (supplementary file) provides the four clinical scenarios added to the follow-up KAP questionnaire.

Table 2.

Number and proportion of respondents * who selected the correct antibiotic or other treatment for each of the five clinical scenarios included in the knowledge, beliefs, and practices (KBP) questionnaire about Ni-Vanuatu health worker’s antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The differences in mean scores between baseline (2018) and follow-up (2022) are provided.

Health workers’ clinical prescribing knowledge was examined. The number of correctly selected antibiotics for each clinical scenario by the professional group were recorded and overall, the baseline compared with follow-up can be found in Table 3. Both professional groups showed a significant improvement in surveys. The difference between total baseline and follow-up mean knowledge scores for all health workers was 1.14 p < 0.001 (95% CI 0.65; 1.62).

Table 3.

Number of correct antibiotics selected by number of respondents according to professional group for the clinical scenarios listed on the knowledge, beliefs, and practices questionnaire about Ni-Vanuatu health workers’ antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The differences in mean knowledge scores between baseline (2018) and follow-up (2022) results are provided.

3.3.2. Pathology Services

Participant’s KBP about microbiology laboratory services were examined in questions and statements about the services offered, selecting specimens for testing, and training attended. Table 4 shows the proportion of respondents who provided positive and/or correct responses to the questions and statements. The differences between the baseline and follow-up questionnaire results are provided.

Table 4.

Number and proportion of respondents * who gave positive and/or correct answers to questions about pathology services included on the knowledge, beliefs, and practices questionnaire about Ni-Vanuatu health workers’ antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The differences between baseline (2018) and follow-up (2022) results are provided.

3.3.3. Interview Responses for Pathology Questions

The face-to-face interview responses revealed health worker concerns about laboratory testing. A doctor reported in a baseline interview, “I think some of the cultures we sent were contaminants, like most of the results we got back. We go backwards. It takes you back to the table”. Timeliness was also a concern amongst some interviewees. Another interviewee reported also at baseline, “sometimes the result takes a week” and another respondent added, “upgrade the lab to be timelier”. A participant requested in a follow-up interview that the antibiogram be updated: “updated antibiogram would help”.

3.4. Beliefs about Prescribing Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance

3.4.1. Confidence in Prescribing Antibiotics

Health worker confidence in prescribing antibiotics was also examined. Table 5. Shows the number of affirmative responses indicating confidence in undertaking the prescribing activities (8) included on the KBP questionnaire. A comparison of the differences between mean scores achieved baseline and follow-up are provided. Table S2 (supplementary file) provides the eight statements listed on the KAP questionnaire used to assess health worker’s antibiotic prescribing confidence.

Table 5.

Number of responses indicating confidence in carrying out the prescribing activities included on the knowledge, beliefs, and practices questionnaire about Ni-Vanuatu health worker’s antibiotic prescribing, antibiotic resistance awareness, and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The difference in mean confidence scores between the baseline (2018) and follow-up (2022) results are provided.

When comparing the baseline and follow-up confidence scores for all respondents across the eight statements, the findings indicated that health workers were significantly less confident in performing the prescribing activities during the pandemic. The difference between baseline and follow-up mean scores for all health workers was −3.77 p < 0.001 (95% CI −1.97; −5.57). There was no correlation in the linear relationship between knowledge and confidence scores r(47) = −0.13, p 0.34 [28].

3.4.2. Knowledge, Beliefs, and Awareness of Antibiotic Resistance

Table 6 shows the questions that examined health worker awareness of ABR listed on the KBP questionnaire. The number and proportion of respondents and their level of agreement are presented at baseline and follow-up and compared.

Table 6.

Number and proportion of respondents and their level of agreement with statements about antibiotic resistance (ABR) included on the knowledge, beliefs, and practices (KBP) questionnaire about Ni-Vanuatu health worker’s antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The differences between the baseline (2018) and follow-up (2022) questionnaire results are provided.

3.5. Practices Regarding Hand Hygiene, Prescribing Antibiotics, and Awareness of Antibiotic Resistance

3.5.1. Infection, Prevention, and Control and Hand Hygiene

Questions and statements about IPC and hand hygiene were included on the KBP questionnaire and Table 6 and Table 8 (below in Section 3.5.2) provide the results of the responses to them.

Participants were also asked in an open-ended question if there were factors which may prevent hand hygiene being performed when hand hygiene was required. There were 25 (51%) and 27 (55%) respondents in the baseline and follow-up questionnaires, respectively, who reported in the affirmative. The results were classified into two groups: lack of supplies and equipment and workload pressures. Table 7 provides the factors reported by the respondents on the baseline and follow-up KBP questionnaires.

Table 7.

A comparison of participant responses to the open-ended question about factors that may prevent hand hygiene performance when required and are listed on the knowledge, beliefs, and practices (KBP) questionnaire about Ni-Vanuatu health workers’ KBP regarding antibiotic prescribing, antibiotic resistance, and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The differences between baseline (2018) and follow-up (2022) questionnaire results are provided.

3.5.2. Antibiotic Prescribing Practices

Table 8 shows the questions and statements listed on the KAP questionnaire about activities related to prescribing, hand hygiene, and the information sources that are used to inform decision-making by the proportion of respondents and their level of agreement. Table S3 (supplementary file) lists reasons why patients may ask for antibiotics when an antibiotic may not be required and the proportion of respondents who selected the reason. Table S4 (supplementary file) shows a list of statements/questions about prescribing, ABR, and training during COVID-19 and the proportion of respondents by professional group who selected the reason.

Table 8.

Number and proportion of respondents and their level of agreement to statements and questions about prescribing practices included on the knowledge, beliefs, and practices (KBP) questionnaire about Ni-Vanuatu health workers’ KBP regarding antibiotic prescribing, antibiotic resistance, and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The differences between baseline (2018) and follow-up (2022) questionnaire results are provided.

At the follow-up, respondents selected the following reasons why they believe patients request antibiotics when an antibiotic is not needed: “perceives antibiotics will make them better when sick” (42; 82%); “travel to hospital is a hardship, so patient asks, just in case” (38; 78%); “unaware of the risk” (32; 76%). Thirteen (13; 26%) respondents selected “patient anxiety due to COVID-19” and 27 (55%), “patient needs reassurance when an antibiotic is unnecessary”. The following participant interview responses supported and clarified these selections:

“Antibiotics most used treatment medicine in all health facilities. People may think antibiotics will heal them when they take it, no matter the problem.”

“If the patient comes from far away then she asks for it just in case she is sick again and it is difficult for her to come back to the hospital for medicine. She lives far and does not have the bus fare.”

“Patients have little knowledge about antibiotics but psychologically they said taking antibiotics makes them feel better.”

“Patients are unaware of antibiotic resistance; they do not have proper consultations with the doctor, and they want to take antibiotics home to store at home for future illness and for family.”

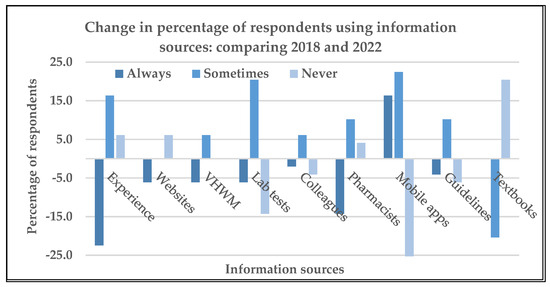

3.5.3. Information Sources

Although usage of information sources to assist with prescribing decisions varied across health workers and between the two questionnaires, the usage of apps on a mobile device was the only tool that obtained significantly higher scores at follow-up compared with the baseline (z = −2.97 p < 0.002). Figure 2 shows the change in percentage of respondents using the various information sources in 2018 compared with those in 2022 listed on the baseline KBP questionnaire. Other sources reported included: “Frank Shann’s Drug Doses”, “information on flow chart algorithms”, “discussions for better antibiotic treatment with clinicians”, and “Allergies and beliefs of the patients”.

Figure 2.

Change in percentage of respondents using the information sources included on the knowledge, beliefs, and practices (KBP) questionnaire about Ni-Vanuatu health workers’ KBP regarding antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance, and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic: 2018 compared with 2022.

3.5.4. Influence of COVID-19 Pandemic on Antibiotic Prescribing and ABR

Thirty-seven (37; 72%) health workers correctly answered the four additional COVID-19–related clinical scenarios. Further information can be found in Tables S1 and S4 (supplementary file), which provide the proportions of health workers who selected the correct antibiotic options for the additional clinical scenarios and agreed with the additional statements/questions listed on the follow-up KBP questionnaire, respectively.

The follow-up questionnaire included an open-ended question that asked health workers whether they thought the COVID-19 pandemic had changed their antibiotic prescribing practice and awareness of ABR and if so, in what way. Sixteen nurses (70%) and 22 (85%) doctors responded in the affirmative. Table 9 provides a representative sample of responses with interpretation.

Table 9.

A representative selection of participant responses to the open-ended question, “Has the COVID-19 pandemic changed your antibiotic prescribing or awareness of antibiotic resistance (ABR) and in what way?” with interpretation.

The following responses were provided by two interviewees when asked whether the pandemic had influenced his antibiotic prescribing and/or awareness of ABR:

A senior doctor reported,

“definitely, and this is because of COVID. COVID has made us really more active when it comes to hand hygiene, hygiene, physical distancing and stuff. AMR is just so much more important. … staff at the hospital are right now more into awareness of antibiotic stewardship. Yes. We are a bit more careful with our choice of antibiotics. … There is a noticeable change in our first line antibiotics….”.

A senior nurse reported,

“Yes. Two years ago, we have hygiene and infection control in the clinic, but it is not good, but now after COVID we have to maintain infection control, we wear masks every day, we wash our hands every now and then when we come in contact with a patient, or between ourselves and colleagues. Also, our surfaces are cleaned enough after each patient compared with two years ago.”

4. Discussion

The results of this study suggest the COVID-19 pandemic influenced antibiotic prescribing and heightened awareness of ABR amongst Ni-Vanuatu health workers.

Knowledge about antibiotic prescribing improved across both professional groups. There are several possible explanations for this improvement: time between the surveys will have enabled health workers to gain more experience and increase their prescribing competency, and discussion amongst colleagues about different treatment regimens has been shown to improve prescribing practice [31]; and pandemic preparedness included “inhouse” training about treatment planning for viral and bacterial infections [32]. Further, responses from interviewees and open-ended questions support the hypothesis that prescribers believed the pandemic may have improved their antibiotic prescribing practices, “changed our prescribing”, “stricter”, “more careful”, ‘’over-emphasising counselling for viral infections now as they do not need to be treated with antibiotics”.

Health workers’ confidence in performing antibiotic prescribing activities during COVID-19 was shown to be less than before the pandemic.

This uncertainty may be less about actual antibiotic prescribing and more a reflection of how health workers were feeling about the impact of the pandemic. Even though Vanuatu had just seven reported cases of COVID-19 until the borders re-opened in mid-2022 [33], health workers may have been feeling stressed and apprehensive at the effect the global pandemic was having on their already stretched health system, limited staff and equipment, and the impending re-opening of the country’s borders. Health workers may also have been concerned about the challenges of managing sick COVID-19 patients given their situation.

Three-quarters of respondents at follow-up reported using bacterial culture results, either always or sometimes when prescribing antibiotics. Although this is a good result, specimen collection and handling, ordering the correct test, and interpreting the result cannot be assumed to be optimal in all cases. A recent study from Ethiopia (2021) stressed the need to use standardised clinical specimen collection procedures for microbiology and accurate diagnosis and treatment [34]. The same study reported that many LMICs lack standardised procedures [34]. Our study suggests that selecting the correct specimens for testing based on clinical presentation may be challenging for some health workers, suggesting that a better understanding of the microbiology is needed to ensure optimal use of the laboratory. Ferguson et al. report proper specimen selection and collection are often challenging in PICTs [35], providing an explanation for the earlier reference to contamination of pre-analytical samples. The findings of an earlier study support this interviewee’s response [36]. Given the results mentioned above, an ASP educational strategy targeting these skills and including interpretation of culture and antibiotic susceptibility results and cumulative antibiograms would enhance prescriber competencies in these areas and ensure appropriate diagnosis and optimal treatment [37].

Although health workers were aware that ABR was a global issue in 2018, their knowledge about ABR in the PICTs and in Vanuatu was limited and did not change during the survey. Prior to 2018, ABR in Vanuatu had not been investigated, though ABR was present in several PICTs [38,39,40]. By the time COVID-19 had emerged, there was evidence of ABR in Vanuatu, although more work needs to be conducted to build a more “complete picture” [36]. The existence of ABR in PICTs is concerning for Vanuatu. Vanuatu’s rate of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is just 3% (13/502) [36], whilst in other PICTs, rates range from between >20% and 60% [35,39,41]. Since tourism is a major source of income for Vanuatu and travel between PICTs is popular, the likelihood of resistant bacteria being introduced by travellers, including other Pacific islanders, presents a very real threat for Vanuatu [42].

Despite findings indicating that health workers have a good knowledge of ABR, this does do not necessarily translate into reducing antibiotic prescribing [43,44]. There are factors which, if not addressed, will hinder progress toward achieving optimal prescribing and containment of ABR, including: lack of ongoing CPD for health workers, absence of or nonadherence to antibiotic guidelines, poor IPC in healthcare settings, and lack of community awareness of ABR [3].

A desire to attend “talkings”, “refresher courses”, and “workshops to inform” was indicated by a high proportion of respondents, suggesting an unmet need for professional education experiences. Health worker engagement in continuous professional development (CPD) is crucial to improving and extending knowledge, enhancing skills, and maintaining prescribing competency [45,46]. The importance of CPD in LMICs where trained staff are in short supply cannot be underestimated [47].

Infection prevention and control is one of the five objectives making up the WHA’s GAP to contain AMR [4]. In the early 2000s, the WHO recognised hand hygiene within IPC as the most effective strategy to prevent and control HCAIs [25]. Studies have shown that optimal performance of hand hygiene can achieve a reduction in HCAIs of between 15% and 30% [48,49]. The value of hand hygiene was highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic [50].

Although there was an improvement in health worker knowledge about IPC, this did not reflect actual hand hygiene practice. The qualitative findings identified obstacles to optimal performance at both baseline and follow-up, including a lack of accessible washing stations, gaps in supplies of soap and hand sanitiser, and lack of time. To ensure adherence to hand hygiene recommendations, the necessary equipment and supplies need to be consistently available at the point-of-care [51]. This may be beyond the capacity of many health systems in LMICs with already stretched budgets. Like many LMIC, Vanuatu is frequently impacted by natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic will have been an added burden on the country’s financial resources.

More than a third of patients requested antibiotics when they may not have been needed. A study from Jordan found a similar result (41%) [52]. A study from Nepal reported that nearly half of patients were given antibiotics when not required. Respondents (medical practitioners) attributed this to patient pressure [53]. Study clinicians spoke of “giving in” to patient expectations knowing the condition was unlikely to be bacterial [53]. An Egyptian study confirmed these findings, citing the only factor significantly associated with the receipt of an antibiotic was the patient or caregiver’s preference that one be prescribed (95.2% (59/82 patients) (p < 0.05) and 88.6% (109/143 caregivers) (p < 0.01)) [54].

Just half of the respondents believed patients who ask for antibiotics need reassurance when an antibiotic is not required. Research into prescriber’s perceptions of a patient’s reasons for requesting antibiotics and the patient’s reasons for doing so is scarce but may clarify misunderstandings [55]. Providing opportunities for health workers to develop communication skills to build relationships and trust with patients has been shown to improve medication adherence and reduce prescribing probability (−6.5% (95% CI −10.7%; −2.3%)) [56]. Further, research has demonstrated that simply explaining why antibiotics are not needed and providing positive treatment advice with an alternate plan for the illness results in reducing unnecessary antibiotic prescribing [57].

In the absence of a national antibiotic guideline, health workers used a wide variety of tools to help them with their treatment decision-making; some may not have been relevant or current. However, in December 2022, Vanuatu’s National Antibiotic Guideline—2022 was released on the Therapeutic Guidelines’ [58] Guideline Host, an online platform which hosts locally developed and endorsed guidelines and protocols for low-resource settings [59]. Ni-Vanuatu prescribers can access the guideline on a mobile device either online or offline when internet access is unreliable. Studies indicate that guidelines that are easy to access have a greater likelihood of being taken up and adhered to [60]. Amongst the respondents, access to mobile devices and the use of online applications was shown to increase significantly between surveys. However, having a guideline available does not guarantee it will be adopted or the recommendations adhered to. An ASP strategy to actively implement, disseminate, monitor, and evaluate the guideline is critical. Engaging stakeholders in each of these processes will engender support and strengthen uptake and compliance [61,62,63].

These authors were unable to identify any studies that investigated the influence of COVID-19 on health workers’ KBP regarding prescribing and awareness of AMR.

The responses to open-ended and interview questions re-affirmed the quantitative results by demonstrating that the majority of participants believe the pandemic influenced their prescribing practices for the better and heightened their awareness of ABR. However, it needs to be noted that the time between surveys (3 years) and other factors may have also contributed to the observed differences between the baseline and follow-up results.

One of the major strengths of this study was the mixed methods design. Employing both quantitative and qualitative research techniques in a study can strengthen the quantitative results [19]. By combining these two techniques, a deeper comprehension of the influence of COVID-19 on Ni-Vanuatu health worker’s KBP regarding antibiotic prescribing and awareness of ABR was gained than by using quantitative techniques alone. The authors believe that this is the first study of its kind to be conducted in Vanuatu and in the PICTs to date.

Even though the study was conducted in the main referral hospital, VCH, the Ni-Vanuatu clinicians move between hospitals when required to cover staff shortages. Although the results cannot be generalised beyond this healthcare setting in Vanuatu, the study may have relevance to similar settings in other PICTs.

Surveys are subject to social bias (acceptable/preferable answers), recall bias on the part of the participants, and interviewer bias from the way questions are asked or responses are received in interviews, and these cannot be ruled out in our study. The open-ended and interview questions did not cover the full range of areas that made up the questionnaire. Therefore, not all the quantitative results had the benefit of added insight from the qualitative research.

5. Future Directions

The study found that knowledge about antibiotic prescribing and ABR improved between surveys and some of their beliefs about prescribing and ABR also changed. Together, these may have influenced their practices. The study highlights some of the challenges that may compromise the performance of prescribers in LMICs.

The following recommendations in support of healthcare workers are suggested: providing ongoing CPD activities to improve knowledge, enhance skills, and maintain competency in antibiotic prescribing; formalising antibiotic stewardship and IPC programmes to optimise prescribing and IPC practices; strengthening relationships between prescribers and patients through communication skills training; and raising community awareness about ABR to support more effective use of medications. These are all age-old guidelines for healthcare workers. Moreover, antibiotic stewardship and IPC strategies are integrated into national hospital accreditation standards for hospitals in high-income countries and are being adopted in many middle-income countries [64]. The National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers for hospitals in India is an example [65].

Finally, the implementation and dissemination of a new national antibiotic guideline calls attention to the importance of monitoring and assessing its use, and ensuring the guideline maintains currency. These will encourage uptake and adherence to the recommendations and inform ASP strategies to promote the best practice in prescribing.

It is hoped that the results of this study can be translatable to other PICTs and can be used to inform ASP strategies across the region.

Supplementary Materials

The following Supplementary Materials can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/tropicalmed8100477/s1, Table S1. Number and proportion of respondents at follow-up who selected the correct treatment options for the five additional clinical scenarios about antibiotic prescribing during COVID-19; Table S2. Statements used to assess the respondent’s level of confidence in performing the prescribing activities. Table S3. Number and proportion of respondents at follow-up who selected one or more of the reasons why patients ask for antibiotics when an antibiotic is not needed. Table S4. Number and proportion of respondents at follow-up who agreed with statements and questions about prescribing, antibiotic resistance, and training during the COVID pandemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.D.F. and L.M.; formal analysis, N.D.F.; investigation, N.D.F., S.A.T. and A.M.; methodology, N.D.F., N.T. and L.M.; supervision, C.L.L.; validation, N.D.F., A.M. and N.T.; visualization, N.D.F. and C.L.L.; writing—original draft, N.D.F.; writing—review and editing, N.D.F., S.A.T., N.T. and C.L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

N.D.F. was supported in this research by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. C.L.L. was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Council Fellowship (grant number: APP1193826). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The questionnaire can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Vanuatu Drugs and Therapeutics Committee, the Vanuatu Ministry of Health for their support throughout this project. We thank Alice Richardson of the ANU Statistical Support Unit for her statistics support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mian, M.; Teoh, L.; Hopcraft, M. Trends in Dental Medication Prescribing in Australia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2021, 6, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-atthe-media-briefing-on-Covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Lucien, M.A.B.; Canarie, M.F.; Kilgore, P.E.; Jean-Denis, G.; Fénélon, N.; Pierre, M.; Cerpa, M.; Joseph, G.A.; Maki, G.; Zervos, M.J.; et al. Antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in the COVID-19 era: Perspective from resource-limited settings. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: http://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509763 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance. Antimicrobial Resistance: National Action Plans. Available online: www.who.int/docs/default-source/antimicrobial-resistance/amr-gcp-tjs/iacg-amr-national-action-plans-110618.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Rossolini, G.M.; Schultsz, C.; Tacconelli, E.; Murthy, S.; Ohmagari, N.; Holmes, A.; Bachmann, T.; Goossens, H.; Canton, R.; et al. Key considerations on the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on antimicrobial resistance research and surveillance. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 115, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawson, T.M.; Ming, D.; Ahmad, R.; Moore, L.S.P.; Holmes, A.H. Antimicrobial use, drug-resistant infections and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, L.; Tolaj, I.; Baftiu, N.; Fejza, H. Use of antibiotics in COVID-19 ICU patients. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 15, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beović, B.; Doušak, M.; Ferreira-Coimbra, J.; Nadrah, K.; Rubulotta, F.; Belliato, M.; Berger-Estilita, J.; Ayoade, F.; Rello, J.; Erdem, H. Antibiotic use in patients with COVID-19: A ‘snapshot’ Infectious Diseases International Research Initiative (ID-IRI) survey. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3386–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Soucy, J.R.; Westwood, D.; Daneman, N.; MacFadden, D.R. Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: Rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, S.; Taylor, A.; Brown, A.; de Kraker, M.E.A.; El-Saed, A.; Alshamrani, M.; Hendriksen, R.S.; Jacob, M.; Löfmark, S.; Perovic, O.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the surveillance, prevention and control of antimicrobial resistance: A global survey. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 3045–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Haque, M.; Shetty, A.; Choudhary, S.; Bhatt, R.; Sinha, V.; Manohar, B.; Chowdhury, K.; Nusrat, N.; Jahan, N.; et al. Characteristics and Management of Children With Suspected COVID-19 Admitted to Hospitals in India: Implications for Future Care. Cureus 2022, 14, e27230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satria, Y.A.A.; Utami, M.S.; Prasudi, A. Prevalence of antibiotics prescription amongst patients with and without COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathog. Glob. Health 2023, 117, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheikh, F.; Goodman, B.; Sindi, O.; Seaton, R.; Kurdi, A. Prevalence of bacterial coinfection and patterns of antibiotics prescribing in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Mustafa, Z.; Salman, M.; Aldeyab, M.; Kow, C.S.; Hasan, S.S. Antimicrobial consumption among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Pakistan. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2021, 3, 1691–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, D.; Graber, C.J. Antimicrobial Stewardship in a Pandemic: Picking Up the Pieces. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, e542–e544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Y.; Chang, P.H.; Chen, K.Y.; Lin, I.F.; Hsih, W.H.; Tsai, W.L.; Chen, J.A.; Lee, S.S. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) associated bacterial coinfection: Incidence, diagnosis and treatment. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2022, 55, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collignon, P. Antibiotic resistance: Are we all doomed? Intern. Med. J. 2015, 45, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.M.; Glover, R.E.; McQuaid, C.F.; Olaru, I.D.; Gallandat, K.; Leclerc, Q.J.; Fuller, N.M.; Willcocks, S.J.; Hasan, R.; van Kleef, E.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance and COVID-19: Intersections and implications. Elife 2021, 10, e64139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social Sciences; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ivankova, N.; Creswell, J.; Stick, S. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Bank Data: Vanuatu. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/vanuatu?view=chart (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Om, C.; Vlieghe, E.; McLaughlin, J.C.; Daily, F.; McLaws, M.L. Antibiotic prescribing practices: A national survey of Cambodian physicians. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 1144–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Patient Safety. Hand Hygiene Technical Reference Manual to Be Used by Healthcare Workers, Trainers and Observers of Hand Hygiene Practices. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44196 (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Vanuatu Ministry of Health. Health Worker’s Manual: Standard Treatment Guidelines, 3rd ed.; Government of Vanuatu: Port Vila, Vanuatu, 2013.

- Vanuatu Ministry of Health. Vanuatu COVID-19 Protocols: April. 2022; Government of Vanuatu: Port Vila, Vanuatu, 2022.

- Fiji Ministry of Health and Medical Services. Fiji Antibiotic Guideline; Government of Fiji: Melbourne, Australia, 2015.

- Marx, R.; Menezes, A.; Horovitz, L. A comparison of two-time intervals for test-retest reliability of health status instruments. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2003, 56, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevalin, D.; Robson, K. The Stata Survival Manual; McGraw-Hill Education: Maidenhead, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kamarudin, G.; Penm, J.; Charr, B.; Moles, R. Educational interventions to improve competency: Systematic review. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxlee, N.; Lui, A.; Mathias, A.; Townell, N.; Lau, C. Antibiotic consumption in Vanuatu before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2018-2021: An interrupted time series analysis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanuatu Ministry of Health. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vanuatu Situation Report: 59. Available online: http://covid-19gov.vu/index.php/situation-reports (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Kue, J.; Bersani, A.; Stevenson, K.; Yimer, G.; Wang, S.; Gebreyes, W.; Hazim, C.; Westercamp, M.; Omondi, M.; Amare, B.; et al. Standardizing clinical culture specimen collection in Ethiopia: A training-of-trainers. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.; Joseph, J.; Kangapu, S.; Zoleveke, H.; Townell, N.; Duke, T.; Manning, L.; Lavu, E. Quality microbiological diagnostics and antmicrobial susceptibility testing, an essential component of antimicrobial resistance surveillance and control efforts in Pacific Island nations. West. Pac. Surveill. Response 2020, 11, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxlee, N.; Townell, N.; Tosul, M.; McIver, L.; Lau, C. Bacteriology and antimicrobial resistance in Vanuatu: January 2017 to December 2019. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J.; Hardy, L.; Semret, M.; Lunguya, O.; Phe, T.; Affolabi, D.; Yansouni, C.; Vandenberg, O. Diagnostic bacteriology in district hospitals in Sub-Saharan Africa: At the forefront of the containment of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colot, J.; Fouquet, C.; Ducrocq, F.; Chevalier, S.; Le Provost, C.; Cazorla, C.; Cheval, C.; Fijalkowski, C.; Gourinat, A.C.; Biron, A.; et al. Prevention and control of highly antibiotic-resistant bacteria in a Pacific territory: Feedback from New Caledonia between 2004 and 2020. Infect. Dis. Now 2022, 52, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foxlee, N.; Townell, N.; McIver, L.; Lau, C. Antibiotic resistance in Pacific Island Countries and Territories: A systematic scoping review. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, M.J.; Young-Sharma, T.; Wati, S.; Badoordeen, G.Z.; Blakeway, L.V.; Byers, S.M.H.; Cheng, A.C.; Jenney, A.W.J.; Naidu, R.; Prasad, A.; et al. Epidemiology, antimicrobial resistance and outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in a tertiary hospital in Fiji: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2022, 22, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesana-Slater, J.; Ritchie, S.R.; Heffernan, H.; Camp, T.; Richardson, A.; Herbison, P.; Norris, P. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Samoa, 2007–2008. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacific Private Sector Development Initiative; Asian Development Bank. Vanuatu: Pacific Tourism Sector Snapshot: November 2021. Available online: Pacificpsdi.org/assets/Uploads/PSDI-TourismSnapshot-VAN2.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Pearson, M.; Chandler, C. Knowing antimicrobial resistance in practice: A multicountry qualitative study with human and animal healthcare professionals. Glob. Health Action 2019, 12, 1599560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, E.E.; Oladele, D.A.; Enwuru, C.A.; Gogwan, P.L.; Abuh, D.; Audu, R.A.; Ogunsola, F.T. Antimicrobial resistance awareness and antibiotic prescribing behavior among healthcare workers in Nigeria: A national survey. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlambo, M.; Silen, C.; McGrath, C. Lifelong learning and nurses’ continuing professional development, a metasynthesis of the literature. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, s12912–s12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, M. The competent prescriber: 12 core competencies for safe prescribing. Aust. Prescr. 2013, 36, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Byungura, J.; Nyiringango, G.; Fors, U.; Forsberg, E.; Tumusiime, D. Online learning for continuous professional development of healthcare workers: An exploratory study on perceptions of healthcare managers in Rwanda. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuckin, M.; Waterman, R.; Govednik, J. Hand hygiene compliance rates in the United States—A one-year multicenter collaboration using product/volume usage measurement and feedback. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2009, 3, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malliarou, M.; Sarafis, P.; Zyga, S.; Constantinidis, T. The importance of nurse’s hand hygiene. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 6, 327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Gammon, J.; Hunt, J. COVID-19 and hand hygiene: The vital importance of hand drying. Br. J. Nurs. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, M.J.; Curtis, S.J.; Naidu, R.; Cheng, A.C.; Jenney, A.W.J.; Mitchell, B.G.; Russo, P.L.; Rafai, E.; Peleg, A.Y.; Stewardson, A.J. Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use among inpatients in a tertiary hospital in Fiji: A point prevalence survey. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2020, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muflih, S.; Al-Azzam, S.; Karasneh, R.; Conway, B.R.; Aldeyab, M. Public health literacy, knowledge, and awareness regarding antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, A.; Hendrie, D.; Selvey, L.A.; Robinson, S. Factors influencing the inappropriate use of antibiotics in the Rupandehi district of Nepal. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2021, 36, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeel, A.; El Shoubary, W.; Hicks, L.; Talaat, M. Patient attitudes and beliefs and provider practices regarding antibiotic use for acute respiratory tract infections in Minya, Egypt. Antibiotics 2014, 3, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, A.; Shano, S.; Khan, M.; Islam, A.; Warren, N.; Hassan, M.; Davis, M. Understanding the social drivers of antibiotic use during COVID-19 in Bangladesh: Implications for reduction of antimicrobial resistance. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strumann, C.; Steinhaeuser, J.; Emcke, T.; Sonnichsen, A.; Goetz, K. Communication training and the prescribing pattern of antibiotic prescription in primary health care. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming-Dutra, K.; Mangion-Smith, R.; Hicks, L. How to Prescribe Fewer Unnecessary Antibiotics: Talking Points that Work with Patients and Their Families. Available online: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2016/0801/p200.html (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Therapeutic Guidelines. The Organisation. Available online: http//www.tg.org.au/the-organisation (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Therapeutic Guidelines. Partnership Program. Available online: http://www.tg.org.au/partnership-program (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Chan, W.; Pearson, T.; Bennett, G.; Cushman, W.; Gaziano, T.; Gorman, P.; Handler, J.; Krumholz, H.; Kushner, R.; Mackenzie, T.; et al. Clinical practice guideline implementation strategies: A summary of systematic reviews by the NHLBI Implementation Science Work Group. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 1076–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.; Silva, S.; Carvalho, V.; Zanghelini, F.; Barreto, J. Strategies for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines in public health: An overview of systematic reviews. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2022, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Guidelines for Guidelines Handbook. Available online: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Franke, A.; Smit, M.; de Veer, A.; Mistiaen, P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: A systematic meta-review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2008, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Integrated Health Services Quality of Care. Health Care Accreditation and Quality of Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240055230 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers. Quality Connect. Available online: http://nbh.co/#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).