Seasonal Dynamics Versus Vertical Stratification of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in an Atlantic Forest Remnant, Brazil: A Focus on the Mansoniini Tribe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Ethics Statement

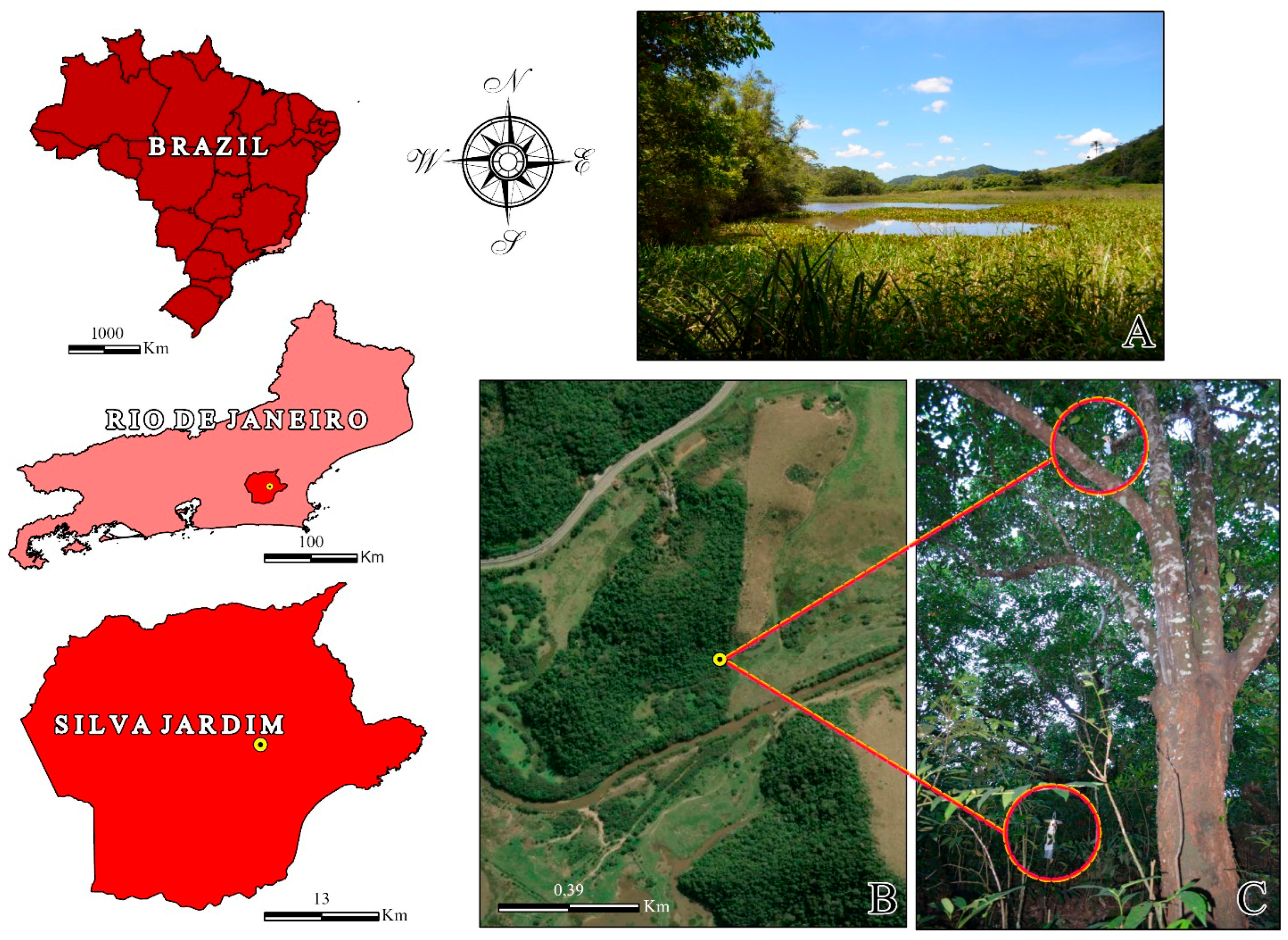

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Mosquito Sampling and Identification

2.4. Morphological Identification

2.5. Georeferencing

2.6. Statistical Analyses

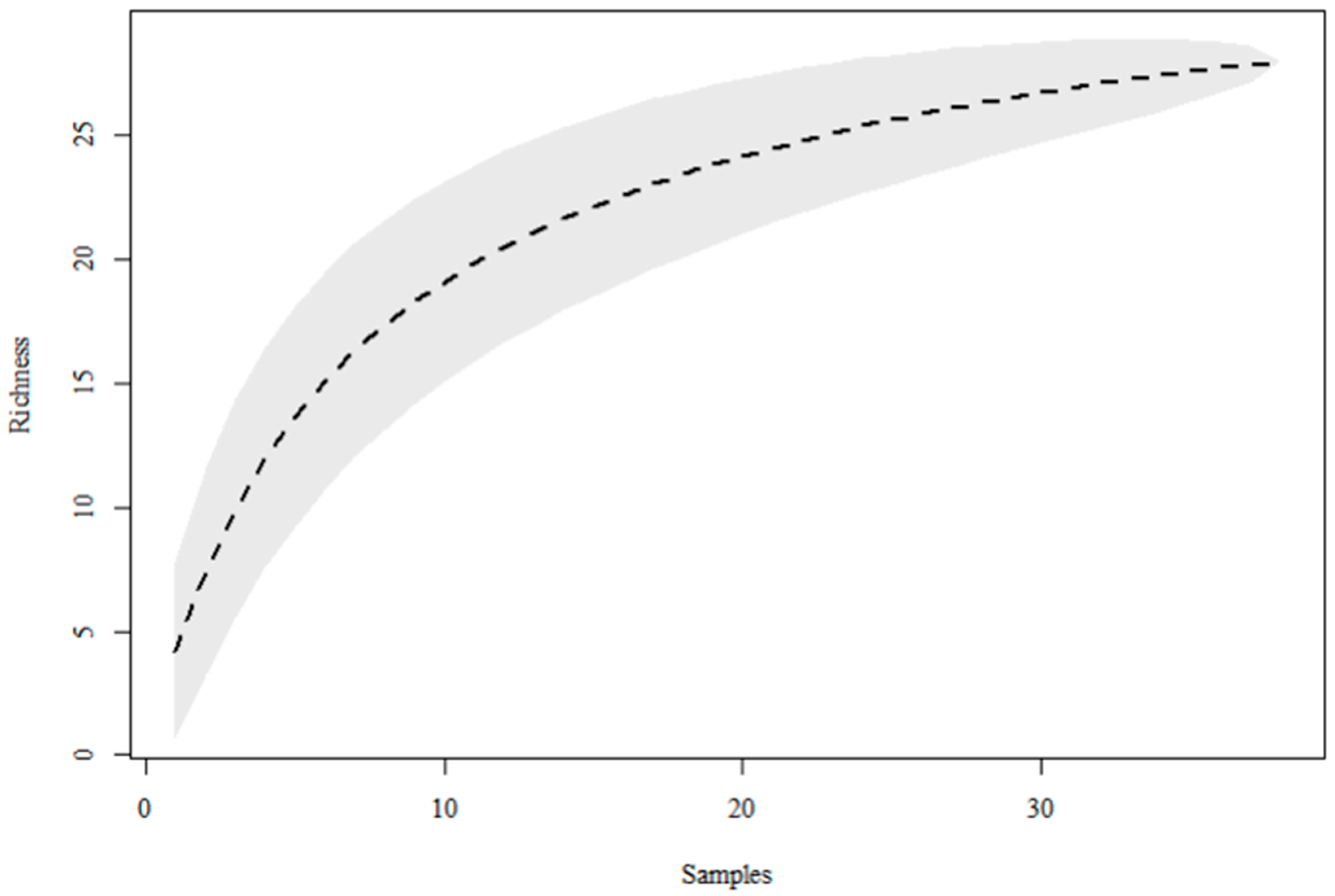

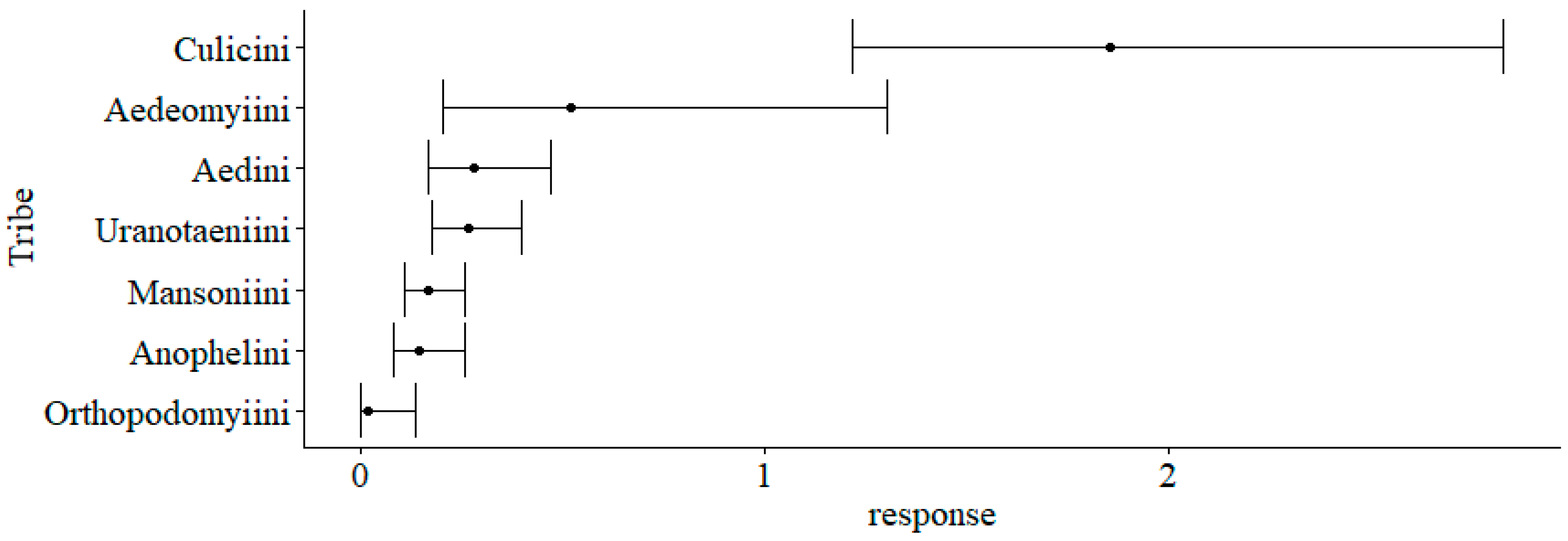

3. Results

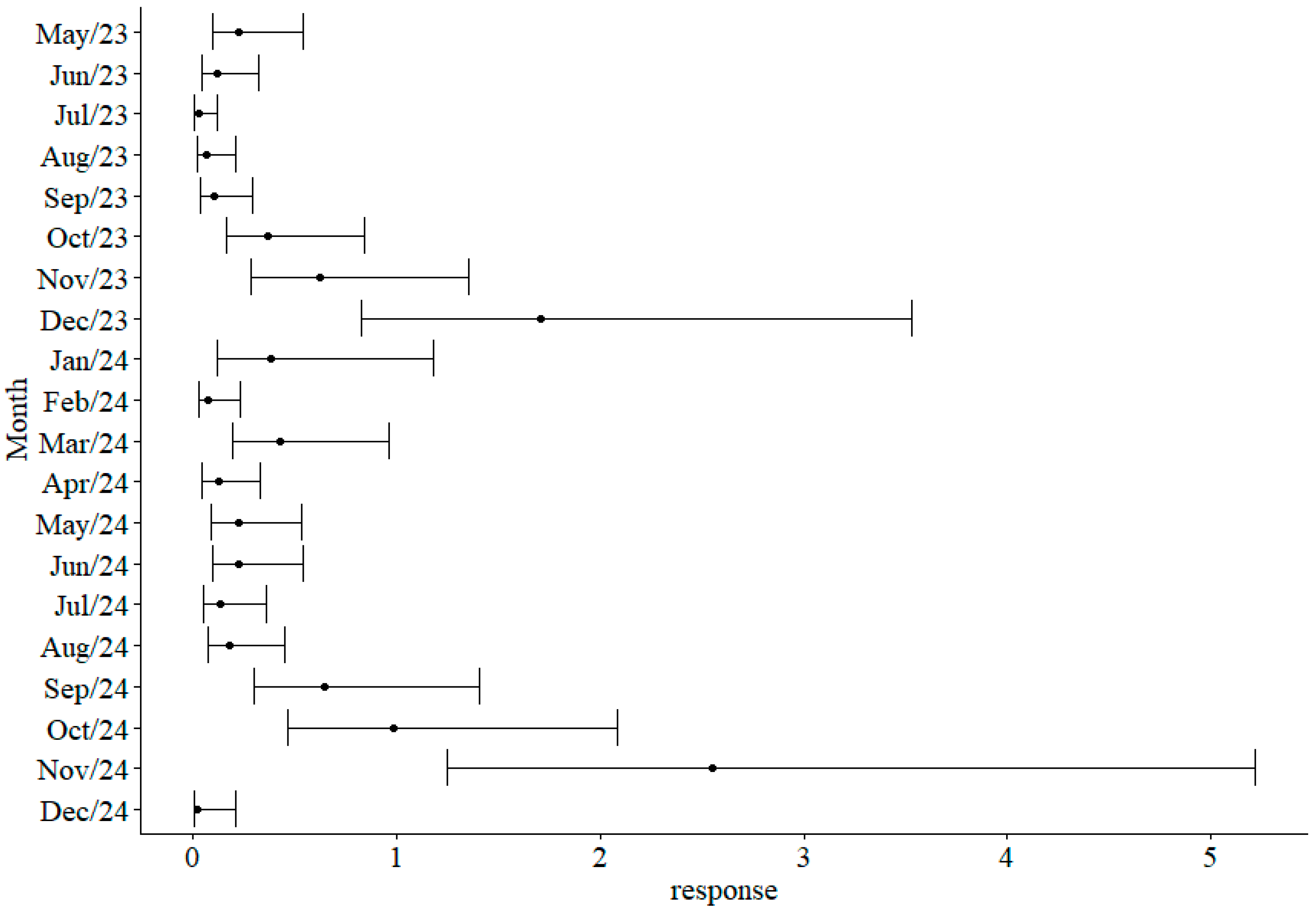

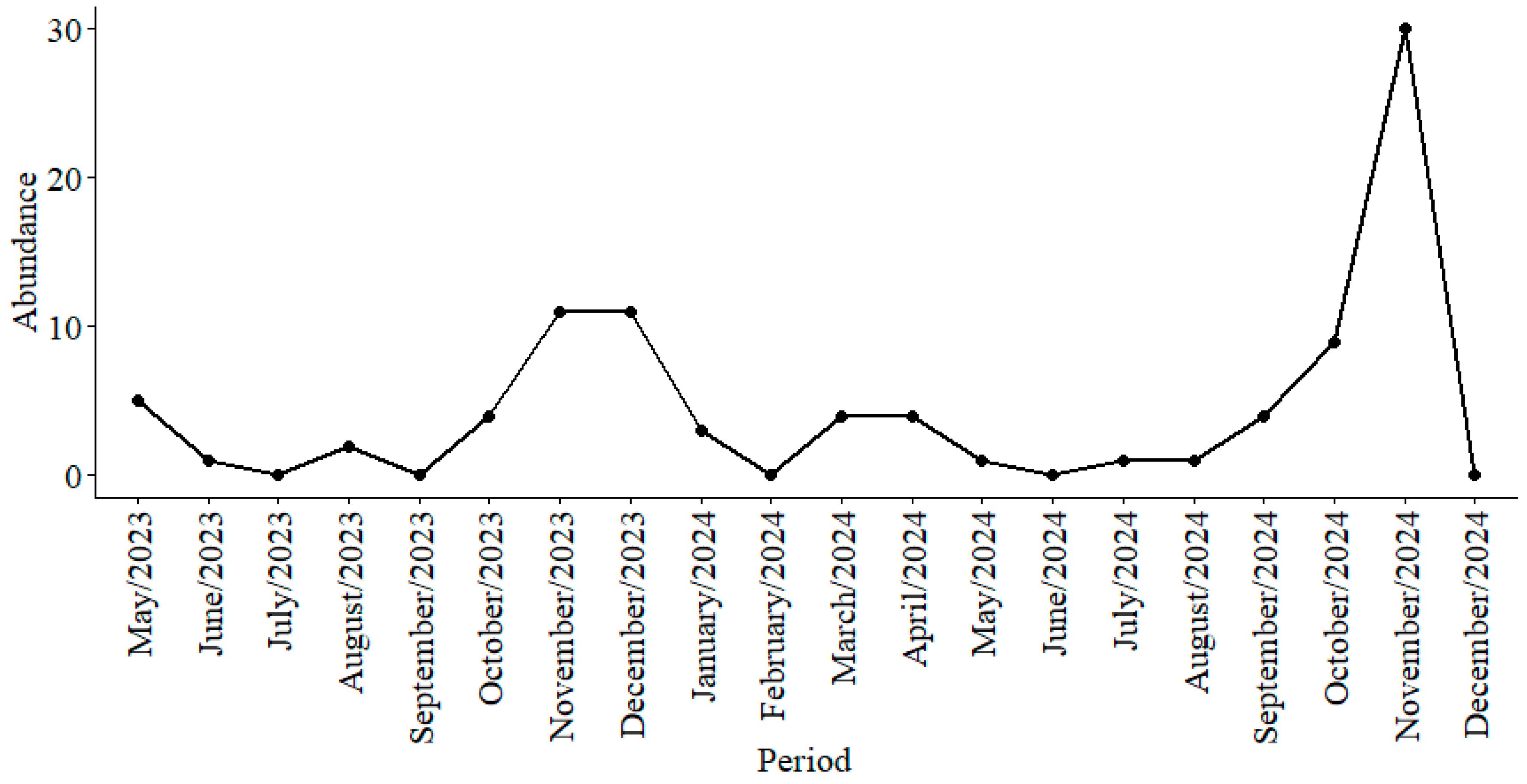

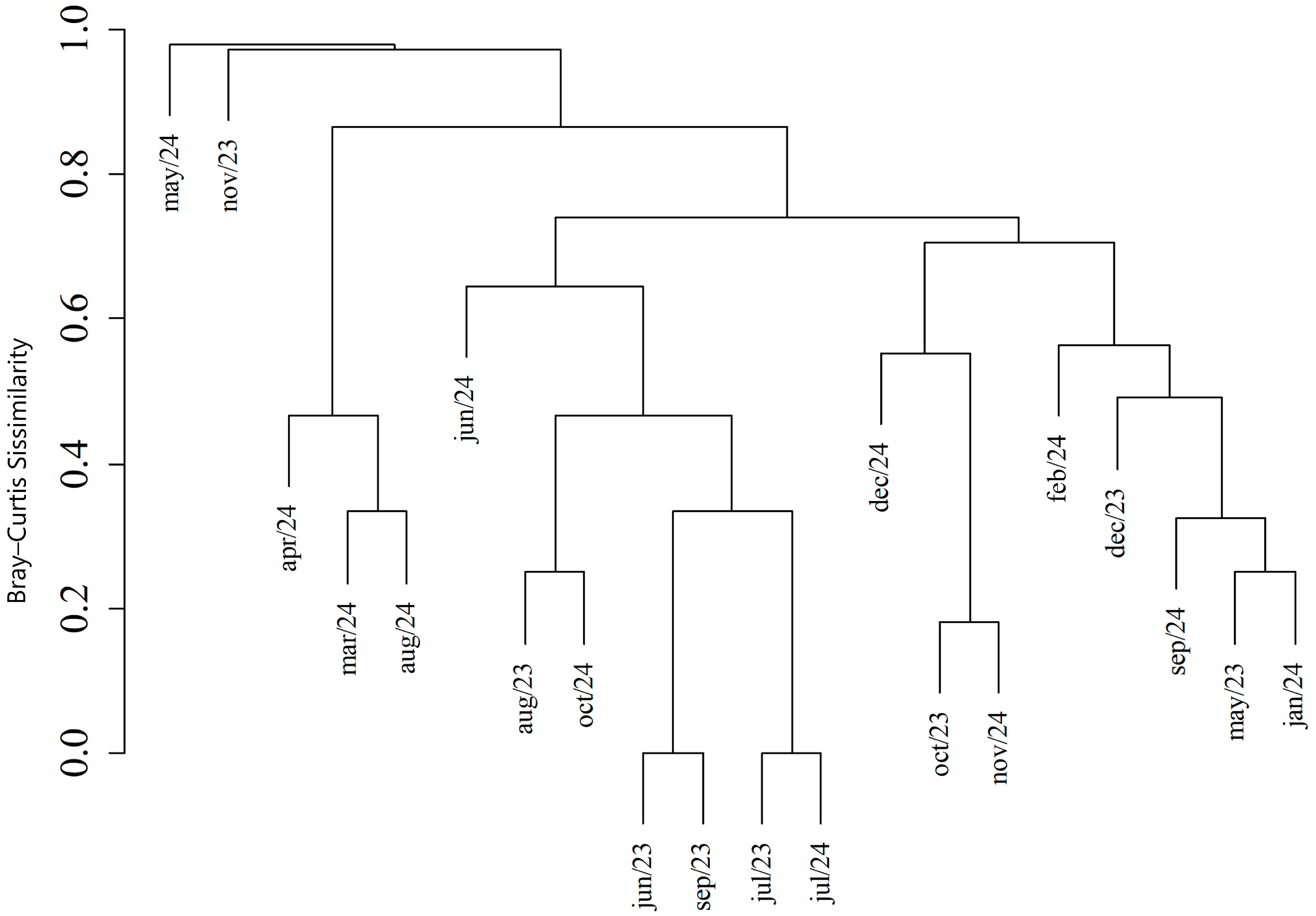

Seasonal Variation in the Mansoniini Tribe

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Service, M. Medical Entomology for Students; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Burkett-Cadena, N.D.; McClure, C.J.W.; Estep, L.K.; Eubanks, M.D. Hosts or habitats: What drives the spatial distribution of mosquitoes? Ecosphere 2013, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol, L.; Remmerswaal, L.; Groen, M.; van der Beek, J.G.; Sikkema, R.S.; Dellar, M.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Geerling, G.W.; Schrama, M. Landscape level associations between birds, mosquitoes and microclimates: Possible consequences for disease transmission? Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, C.S.; Confalonieri, U.E.C.; Mascarenhas, B.M. Ecology of Haemagogus sp. and Sabethes sp. (Diptera: Culicidae) in relation to the microclimates of the Caxiuanã National Forest, Pará, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.; de Mello, C.F.; Santos, G.S.; Carbajal-de-la-Fuente, A.L.; Alencar, J. Vertical distribution of oviposition and temporal segregation of arbovirus vector mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in a fragment of the Atlantic Forest, State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deane, L.M.; Neto, J.A.F.; Lima, M.M. The vertical dispersion of Anopheles (Kerteszia) cruzi in a forest in southern Brazil suggests that human cases of malaria of simian origin might be expected. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1984, 79, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, A.; Valério, D.; Fé, N.F.; Hernandez-Acosta, E.; Mendonça, C.; Andrade, E.; Pedrosa, I.; Costa, E.R.; Júnior, J.T.A.; Assunção, F.P.; et al. Microclimate and the vertical stratification of potential bridge vectors of mosquito-borne viruses captured by nets and ovitraps in a central Amazonian forest bordering Manaus, Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brant, H.L.; Ewers, R.M.; Vythilingam, I.; Drakeley, C.; Benedick, S.; Mumford, J.D. Vertical stratification of adult mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) within a tropical rainforest in Sabah, Malaysia. Malar. J. 2016, 15, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, L.M.; Damasceno, R.G.; Arouck, R. Distribuição vertical de mosquitos em uma floresta dos arredores de Belém, Pará. Folia Clin. Biol. 1953, 20, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Trapido, H.; Galindo, P. Mosquitoes Associated with Sylvan Yellow Fever Near Almirante, Panama. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1957, 6, 114–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forattini, O.P. Culicidologia Médica: Identificação, Biologia, Epidemiologia; EDUSP: Sâo Paulo, Brazil, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tissot, A.C.; Navarro-Silva, M.A. Preferência por hospedeiro e estratificação de Culicidae (Diptera) em área de remanescente florestal do Parque Regional do Iguaçu, Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Zool. 2004, 21, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbach, R.E. Composition and Nature of the Culicidae (Mosquitoes); CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, G.J. Method of attachment of pupae of Mansonia annulifera (Theo.) and M. uniformis (Theo.) to Pistia stratiotes. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1965, 55, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, J.F.; Barroso, J.F.D.S.; Neto, N.F.S.; Furtado, N.V.R.; Carvalho, D.P.; Ribeiro, K.A.; Lima, J.B.P.; Galardo, A.K.R. Oviposition activity of Mansonia species in areas along the Madeira River, Brazilian Amazon rainforest. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 2023, 39, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, L.H.S.; Mello, C.F.; Silva, J.D.S.; Oliveira, J.D.S.; Silva, S.O.F.; Rodríguez-Planes, L.; Da Costa, F.M.; Alencar, J. Evaluation of Mansonia spp. Infestation on Aquatic Plants in Lentic and Lotic Environments of the Madeira River Basin in Porto Velho, Rondônia, Brazil. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 2021, 37, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, F.A.D.S.; Costa, F.M.D.; Gouveia, A.S.; Roque, R.A.; Tadei, W.P.; Scarpassa, V.M. Bioecological aspects of species of the subgenus Mansonia (Mansonia) (Diptera: Culicidae) prior to the installation of hydroelectric dams on the Madeira River, Rondônia state, Brazil. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, J.; Hotez, P.J.; Junghanss, T.; Kang, G.; Lalloo, D.; White, N.J.; Garcia, P.J. Manson’s Tropical Diseases E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hendy, A.; Hernandez-Acosta, E.; Valério, D.; Mendonça, C.; Costa, E.R.; Júnior, J.T.A.; Assunção, F.P.; Scarpassa, V.M.; Gordo, M.; Fé, N.F.; et al. The vertical stratification of potential bridge vectors of mosquito-borne viruses in a central Amazonian forest bordering Manaus, Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, T.H. A Survey of Trinidadian Arthropods for Natural Virus Infections (August, 1953, to December, 1958). Mosq. News 1960, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken, T.H.G.; Downs, W.G.; Anderson, C.R.; Spence, L.; Casals, J. Mayaro virus isolated from a Trinidadian mosquito, Mansonia venezuelensis. Science 1960, 131, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, F.B.; de Curcio, J.S.; Silva, L.D.C.; da Silva, D.M.F.; Salem-Izacc, S.M.; Anunciação, C.E.; Ribeiro, B.M.; Garcia-Zapata, M.T.A.; de Paula Silveira-Lacerda, E. Report of natural Mayaro virus infection in Mansonia humeralis (Dyar & Knab, Diptera: Culicidae). Parasites Vectors 2023, 16, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, P.V.; Estrada-Franco, J.G.; Navarro-Lopez, R.; Ferro, C.; Haddow, A.D.; Weaver, S.C. Endemic Venezuelan equine encephalitis in the Americas: Hidden under the dengue umbrella. Future Virol. 2011, 6, 721–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Terán, C.; Calderón-Rangel, A.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.; Mattar, S. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus: The problem is not over for tropical America. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICMBio. Plano de Manejo Integrado do Fogo Reserva Biológica de Poço das Antas—NGI ICMBio Mico-Leão-Dourado; Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2022.

- ICMBio. Plano de Manejo da Área de Proteção Ambiental da Bacia do Rio São João/Mico-Leão-Dourado; Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2008.

- Lane, J. Neotropical Culicidae; University of São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Consoli, R.A.G.B.; Oliveira, R.L. Principais Mosquitos de Importância Sanitária no Brasil; Editora da Fundação Oswaldo Cruz: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Assumpção, I.C. Chave de Identificação Pictórica para o Subgênero Mansonia Blanchard, 1901 (Diptera, Culicidae) da Região Neotropical. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil, 2009; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, A.A. Revisão do Subgênero Mansonia Blanchard, 1901 (Diptera, Culicidae) e Estudo Filogenético de Mansoniini. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil, 2007; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, J.F. List of abbreviations for currently valid generic-level taxa in family Culicidae (Diptera). Eur. Mosq. Bull. 2009, 27, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Forattini, O.P.; Gomes, A.D.C.; Natal, D.; Kakitani, I.; Marucci, D. Preferências alimentares e domiciliação de mosquitos Culicidae no Vale do Ribeira, São Paulo, Brasil, com especial referência a Aedes scapularis e a Culex (Melanoconion). Rev. Saúde Pública 1989, 23, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Confalonieri, U.E.; Neto, C.C. Diversity of mosquito vectors (Diptera: Culicidae) in caxiuanã, pará, Brazil. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2012, 2012, 741273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mello, C.F.; Figueiró, R.; Roque, R.A.; Maia, D.A.; da Costa Ferreira, V.; Guimarães, A.É.; Alencar, J. Spatial distribution and interactions between mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) and climatic factors in the Amazon, with emphasis on the tribe Mansoniini. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.L.M.; Pereira, E.S.; Har, N.T.F.; Hamada, N. Mansonia spp. (Diptera: Culicidae) associated with two species of macrophytes in a Varzea lake, Amazonas, Brazil. Entomotropica 2003, 18, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva, J.F.; Furtado, N.V.R.; Maitra, A.; Carvalho, D.P.; Galardo, A.K.R.; Lima, J.B.P. Trends of Mansonia (Diptera, Culicidae, Mansoniini) in Porto Velho: Seasonal patterns and meteorological influences. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 10 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Aedeomyiini | ||||||

| Aedeomiya squamipennis (Lynch Arribálzaga, 1878) | 11 | 3.1 | 37 | 7.0 | 48 | 5.5 |

| Aedini | ||||||

| Aedes rhyacophilus da Costa Lima, 1933 | 16 | 4.6 | 24 | 4.5 | 40 | 4.5 |

| Aedes scapularis (Rondani, 1848) | 43 | 12.3 | 95 | 18.0 | 138 | 15.7 |

| Aedes serratus S.l (Theobald, 1901) | 1 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.6 |

| Psorophora ferox (Humboldt, 1819) | - | - | 3 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.3 |

| Anophelini | ||||||

| Anopheles evansae (Brèthes, 1926) | 3 | 0.9 | 7 | 1.3 | 10 | 1.1 |

| Anopheles kompi Edwards, 1930 | - | - | 3 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.3 |

| Anopheles triannulatus (Neiva & Pinto, 1922) | 4 | 1.1 | 16 | 3.0 | 20 | 2.3 |

| Culicini | ||||||

| Culex (Culex) sp. | 26 | 7.4 | 72 | 13.6 | 98 | 11.1 |

| Culex (Melanoconion) sp. | 150 | 42.7 | 164 | 31.0 | 314 | 35.7 |

| Culex (Microculex) davisi | 1 | 0.3 | - | - | 1 | 0.1 |

| Culex (Microculex) pleuristriatus | 1 | 0.3 | - | - | 1 | 0.1 |

| Mansoniini | ||||||

| Coquillettidia chrysonotum (Peryassú, 1922) | 7 | 2.0 | 7 | 1.3 | 14 | 1.6 |

| Coquillettidia fasciolata (Lynch Arribálzaga, 1891) | 16 | 4.6 | 17 | 3.2 | 33 | 3.8 |

| Coquillettidia venezuelensis (Theobald, 1912) (in Surcouf, 1912) | 4 | 1.1 | 4 | 0.8 | 8 | 0.9 |

| Mansonia humeralis Dyar & Knab, 1916 | 2 | 0.6 | - | - | 2 | 0.2 |

| Mansonia indubitans Dyar & Shannon, 1925 | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Mansonia pseudotitillans (Theobald, 1901) | 3 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Mansonia titillans (Walker, 1848) | 8 | 2.3 | 18 | 3.4 | 26 | 3.0 |

| Orthopodomyiini | ||||||

| Orthopodomyia albicosta (Lutz, 1904) (in Bourroul, 1904) | - | - | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Uranotaeniini | ||||||

| Uranotaenia apicalis Theobald, 1903 | 13 | 3.7 | 5 | 0.9 | 18 | 2.0 |

| Uranotaenia briseis Dyar 1925 | 2 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.6 |

| Uranotaenia geometrica Theobald, 1901 | 7 | 2.0 | 13 | 2.5 | 20 | 2.3 |

| Uranotaenia hystera Dyar & Knab, 1913 | 16 | 4.6 | 13 | 2.5 | 29 | 3.3 |

| Uranotaenia lowii Theobald, 1901 | 9 | 2.6 | 12 | 2.3 | 21 | 2.4 |

| Uranotaenia pulcherrima Lynch Arribálzaga, 1891 | 7 | 2.0 | 5 | 0.9 | 12 | 1.4 |

| Uranotaenia sp. | - | - | 2 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Total | 351 | 100 | 529 | 100 | 880 | 100 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | z-Value | Pr (>|z|) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −1.27 | 0.67 | −1.9 | 0.058 | |

| Aedini | −0.61 | 0.53 | −1.1 | 0.250 | |

| Tribe: Anophelini 1 | −1.27 | 0.55 | −2.3 | 0.021 | * |

| Tribe: Culicini 1 | 1.27 | 0.51 | 2.5 | 0.013 | * |

| Tribe: Mansoniini 1 | −1.13 | 0.51 | −2.2 | 0.027 | * |

| Tribe: Orthopodomyiini 1 | −3.37 | 1.13 | −3.0 | 0.003 | ** |

| Tribe: Uranotaeniini | −0.66 | 0.51 | −1.3 | 0.189 | |

| Period: Aug/23 | −0.62 | 0.74 | −0.8 | 0.397 | |

| Period: Aug/24 | 0.39 | 0.65 | 0.6 | 0.554 | |

| Period: Dec/23 2 | 2.63 | 0.59 | 4.5 | <0.001 | *** |

| Period: Dec/24 | −1.62 | 1.19 | −1.4 | 0.173 | |

| Period: Feb/24 | −0.48 | 0.72 | −0.7 | 0.502 | |

| Period: Jan/24 | 1.12 | 0.74 | 1.5 | 0.128 | |

| Period: Jul/23 | −1.56 | 0.89 | −1.8 | 0.080 | |

| Period: Jul/24 | 0.10 | 0.67 | 0.1 | 0.886 | |

| Period: Jun/23 | −0.04 | 0.68 | −0.1 | 0.949 | |

| Period: Jun/24 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.9 | 0.344 | |

| Period: Mar/24 2 | 1.25 | 0.61 | 2.0 | 0.041 | * |

| Period: May/23 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.9 | 0.344 | |

| Period: May/24 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.9 | 0.358 | |

| Period: Nov/23 2 | 1.62 | 0.60 | 2.7 | 0.007 | ** |

| Period: Nov/24 2 | 3.03 | 0.59 | 5.2 | <0.001 | *** |

| Period: Oct/23 | 1.10 | 0.62 | 1.8 | 0.075 | |

| Period: Oct/24 2 | 2.08 | 0.60 | 3.5 | <0.001 | *** |

| Period: Sep/23 | −0.16 | 0.69 | −0.2 | 0.811 | |

| Period: Sep/24 2 | 1.66 | 0.60 | 2.8 | 0.006 | ** |

| Height: 10 m | −0.01 | 0.20 | 0.0 | 0.974 |

| Species | Season | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry | Rainy | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Coquillettidia chrysonotum | 8 | 25.0 | 6 | 10.2 |

| Coquillettidia fasciolata | 13 | 40.6 | 20 | 33.9 |

| Coquillettidia venezuelensis | - | - | 8 | 13.6 |

| Mansonia humeralis | 2 | 6.3 | - | - |

| Mansonia indubitans | 1 | 3.1 | 3 | 5.1 |

| Mansonia pseudotitillans | - | - | 4 | 6.8 |

| Mansonia titillans | 8 | 25.0 | 18 | 30.5 |

| Taxa (S) | 5 | 6 | ||

| Abundance (N) | 32 | 59 | ||

| Shannon (H’) | 1.341 | 1.566 | ||

| Pielou (J’) | 0.833 | 0.874 | ||

| Jaccard index (Ji) | 0.429 | |||

| Estimate | Std. Error | z-Value | Pr (>|z|) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −11.205 | 0.5175 | −2.165 | 0.0304 | * |

| Species: Coquillettidia fasciolata | 0.9038 | 0.5888 | 1.535 | 0.1248 | |

| Species: Coquillettidia venezuelensis | −0.6994 | 0.6978 | −1.002 | 0.3163 | |

| Species: Mansonia humeralis 1 | −17.300 | 0.8782 | −1.970 | 0.0488 | * |

| Species: Mansonia indubitans | −12.140 | 0.7715 | −1.574 | 0.1156 | |

| Species: Mansonia pseudottillitans | −12.886 | 0.7847 | −1.642 | 0.1005 | |

| Species: Mansonia tillitans | 0.6744 | 0.5973 | 1.129 | 0.2589 | |

| Seasonal period: Rainy 2 | 12.575 | 0.6006 | 2.094 | 0.0363 | * |

| Temperature | 0.2992 | 0.2920 | 1.025 | 0.3056 | |

| Humidity | −0.1228 | 0.2674 | −0.459 | 0.6459 | |

| Rainfall | −0.1371 | 0.3186 | −0.430 | 0.6669 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mello, C.F.d.; Azevedo, W.T.d.A.; Silva, S.O.F.; Alves, S.C.; Alencar, J. Seasonal Dynamics Versus Vertical Stratification of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in an Atlantic Forest Remnant, Brazil: A Focus on the Mansoniini Tribe. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2026, 11, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11020039

Mello CFd, Azevedo WTdA, Silva SOF, Alves SC, Alencar J. Seasonal Dynamics Versus Vertical Stratification of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in an Atlantic Forest Remnant, Brazil: A Focus on the Mansoniini Tribe. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2026; 11(2):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11020039

Chicago/Turabian StyleMello, Cecília Ferreira de, Wellington Thadeu de Alcantara Azevedo, Shayenne Olsson Freitas Silva, Samara Campos Alves, and Jeronimo Alencar. 2026. "Seasonal Dynamics Versus Vertical Stratification of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in an Atlantic Forest Remnant, Brazil: A Focus on the Mansoniini Tribe" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 11, no. 2: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11020039

APA StyleMello, C. F. d., Azevedo, W. T. d. A., Silva, S. O. F., Alves, S. C., & Alencar, J. (2026). Seasonal Dynamics Versus Vertical Stratification of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in an Atlantic Forest Remnant, Brazil: A Focus on the Mansoniini Tribe. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 11(2), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11020039