Development and Validation of an Integrated HIV/STI, and Pregnancy Prevention Programme: Improving Adolescent Sexual Health Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

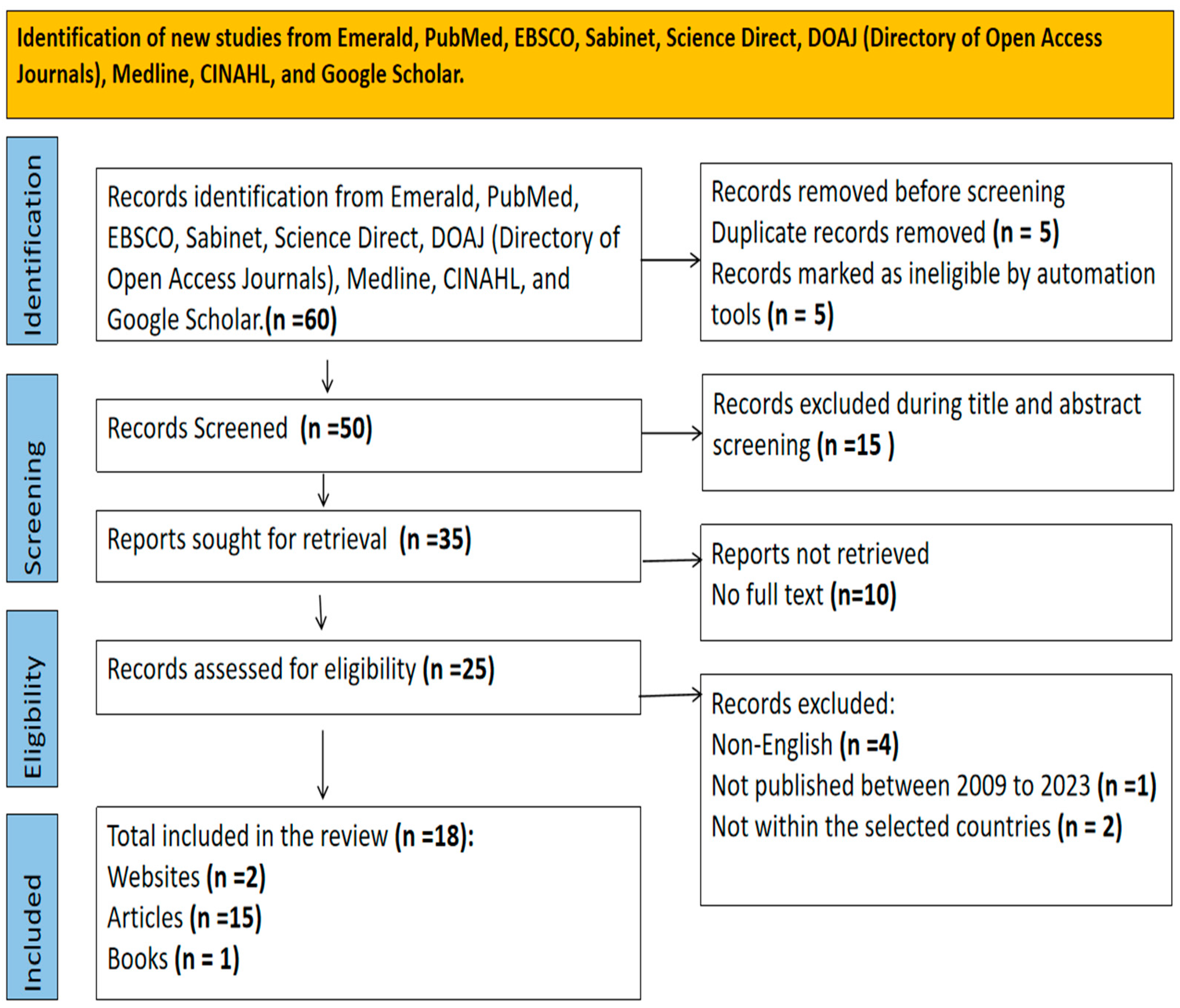

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preliminary Analysis

2.1.1. Merging Data from Four Papers

2.1.2. PEST Analysis

2.1.3. SWOT Analysis

3. Results

| First Paper Findings (Comprehensive Literature Review) | Second Paper Finding (Quantitative Cross-Sectional Study) | Third Paper Findings (Exploratory Qualitative Study) | Fourth Paper Findings (Exploratory Qualitative Study) | Merged Analysis Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Contributing factors

|

| Institutional challenges encountered.

| Barriers to integrate HIV prevention into family planning services.

| Key factors driving PrEP and FP services.

|

3.1. PEST Analysis Outcome

3.2. SWOT Analysis Outcome

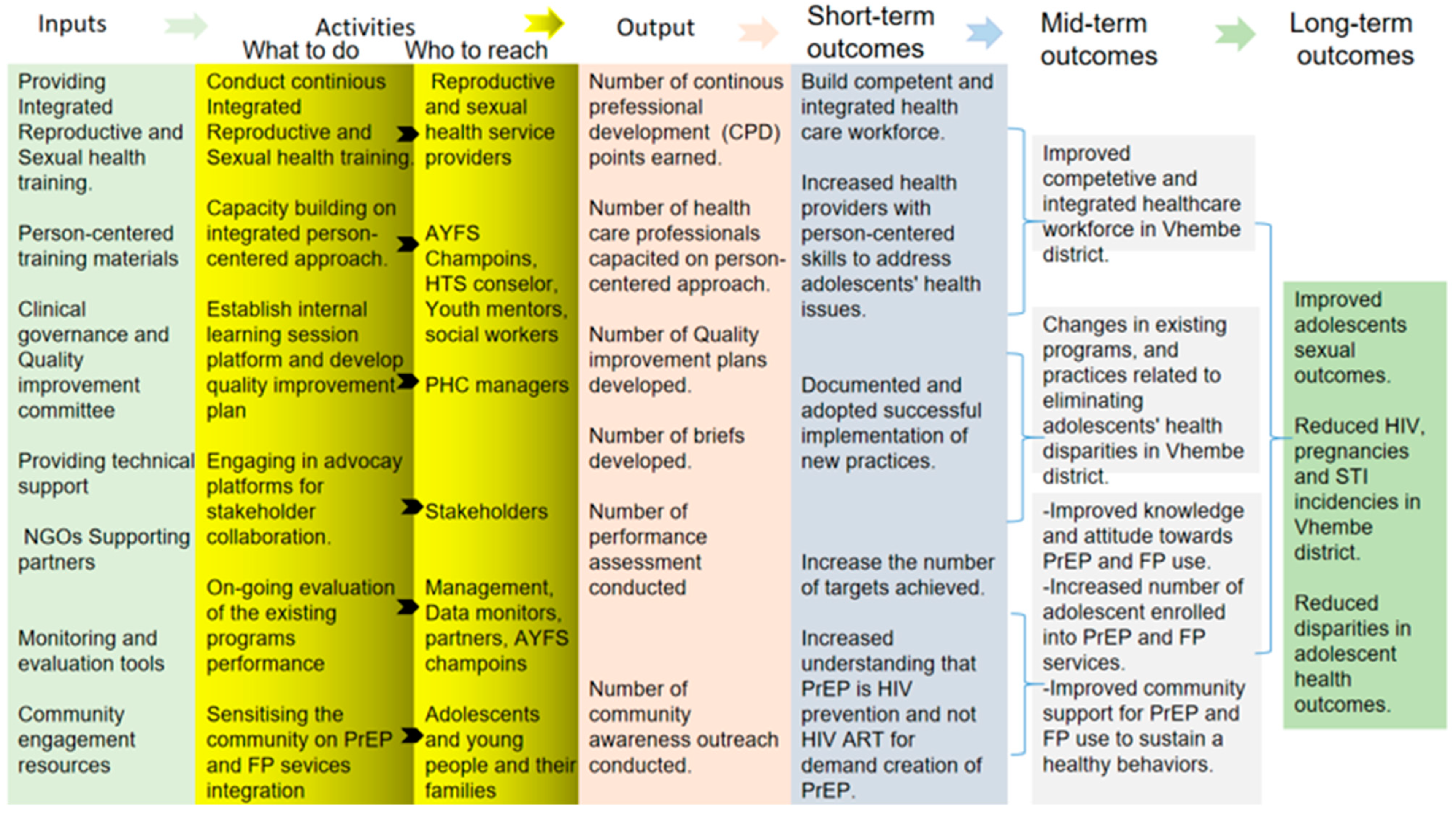

3.3. Application of the Logical Framework Analysis (LFA)

3.4. Programme Design

3.5. Programme Validation

Reducing the Risk (RTR) Coalition Outcome

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, M. South Africa’s Population. 2025. Available online: https://southafrica-info.com/people/south-africa-population/amp/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Uka, V.K.; White, H.; Smith, D.M. The sexual and reproductive health needs and preferences of youths in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-synthesis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, K.; Nyamaruze, P.; Cowden, R.G.; Pillay, Y.; Bekker, L.-G. Children and young women in eastern and southern Africa are key to meeting 2030 HIV targets: Time to accelerate action. Lancet HIV 2023, 10, e343–e350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, V.; Moodley, D.; Naidoo, M.; Connoly, C.; Ngcapu, S.; Karim, Q.A. High incidence of asymptomatic genital tract infections in pregnancy in adolescent girls and young women: Need for repeat aetiological screening. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2023, 99, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L.; Kharsany, A.B.; Humphries, H.; Maughan-Brown, B.; Beckett, S.; Govender, K.; Cawood, C.; Khanyile, D.; George, G. HIV incidence and associated risk factors in adolescent girls and young women in South Africa: A population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allana, A.; Tavares, W.; Pinto, A.D.; Kuluski, K. Designing and governing responsive local care systems–insights from a scoping review of paramedics in integrated models of care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2022, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, N. Public health and care delivery: Similar missions, separate paths. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Adolescent Pregnancy. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- UNICEF. Gender Equality: Global Annual Results Report 2022; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nyemba, D.C.; Medina-Marino, A.; Peters, R.P.; Klausner, J.D.; Ngwepe, P.; Myer, L.; Johnson, L.F.; Davey, D.J. Prevalence, incidence and associated risk factors of STIs during pregnancy in South Africa. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2021, 97, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitneni, P.; Bwana, M.B.; Muyindike, W.; Owembabazi, M.; Kalyebara, P.K.; Byamukama, A.; Mbalibulha, Y.; Smith, P.M.; Hsu, K.K.; Haberer, J.E. STI prevalence among men living with HIV engaged in safer conception care in rural, southwestern Uganda. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Global Health Sector Strategies on, Respectively, HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections for the Period 2022–2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ki-moon, B. The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030). Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/child-health/the-global-strategy-for-women-s-children-s-and-adolescents-health-2016-2030.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Mafokwane, T.M.; Samie, A. Prevalence of chlamydia among HIV positive and HIV negative patients in the Vhembe District as detected by real time PCR from urine samples. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umubyeyi, B.S. Curbing Teenage Pregnancy in South Africa’s Schools. Dhaulagiri J. Sociol. Anthropol. 2024, 18, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stats, S. Mid-Year Population Estimates 2022; Stats SA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health Republic of South Africa. Annual Report 2020/21. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202201/healthannualreport.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Twalo, T. Challenges in the Prevention and Management of Adolescent Pregnancy and School Dropout by Adolescent Mothers in South Africa. Res. Educ. Policy Manag. 2024, 6, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, O.V.; Ajayi, A.I.; Moyaki, M.G.; Goon, D.T.; Avramovic, G.; Lambert, J. High rate of unplanned pregnancy in the context of integrated family planning and HIV care services in South Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. People-Centred and Integrated Health Services: An Overview of the Evidence: Interim Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Continuity and Coordination of Care: A Practice Brief to Support Implementation of the WHO Framework on Integrated People-Centred Health Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shamu, S.; Shamu, P.; Khupakonke, S.; Farirai, T.; Chidarikire, T.; Guloba, G.; Nkhwashu, N. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) awareness, attitudes and uptake willingness among young people: Gender differences and associated factors in two South African districts. Glob. Health Action 2021, 14, 1886455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleaner, M.; Scorgie, F.; Martin, C.; Butler, V.; Muhwava, L.; Mojapele, M.; Mullick, S. Introduction and integration of PrEP and sexual and reproductive health services for young people: Health provider perspectives from South Africa. Front. Reprod. Health 2023, 4, 1086558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.; Subedar, H.; Letsoko, M.; Makua, M.; Pillay, Y. Teenage births and pregnancies in South Africa, 2017–2021–a reflection of a troubled country: Analysis of public sector data. S. Afr. Med. J. 2022, 112, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey-Faussett, P.; Frescura, L.; Abdool-Karim, Q.; Clayton, M.; Ghys, P.D. HIV prevention for the next decade: Appropriate, person-centred, prioritised, effective, combination prevention. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1004102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, P.; Mehou-Loko, C.; Maphumulo, N.; Radzey, N.; Abrahams, A.G.; Sibeko, S.; Harryparsad, R.; Manhanzva, M.; Meyer, B.; Radebe, P. Differences in HIV risk factors between South African adolescents and adult women and their association with sexually transmitted infections. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2025, 101, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammela, M.; Makhado, L. Evaluating the Implementation of Adolescent-and Youth-Friendly Services in the Selected Primary Healthcare Facilities in Vhembe District, Limpopo Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adzhienko, V.; Soboleva, S.; Shuliko, D.; Orobinskaya, V. PEST-Analysis of Factors of Medical Workers’ Professional Burnout. In Proceedings of the VIII International Scientific and Practical Conference ’Current Problems of Social and Labour Relations’ (ISPC-CPSLR 2020), Makhachkala, Russia, 17–18 December 2020; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, C.; Santos, M.; Portela, F. A SWOT Analysis of Big Data in Healthcare. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health, ICT4AWE 2020, Prague, Czech Republic, 3–5 May 2020; Volume 1, pp. 256–263, ISBN 978-989-758-420-6, ISSN 2184-4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, S.; Augusto, O.; Fernandes, Q.; Gimbel, S.; Ramiro, I.; Uetela, D.; Tembe, S.; Kimball, M.; Manaca, M.; Anderson, C.L. Primary health care management effectiveness as a driver of family planning service readiness: A cross-sectional analysis in central Mozambique. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2022, 10, e2100706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musuka, G.; Mukandavire, Z.; Murewanhema, G.; Chingombe, I.; Cuadros, D.F.; Mutenherwa, F.; Dzinamarira, T.; Eghtessadi, R.; Malunguza, N.; Mapingure, M. HIV and Contraceptive Use in Zimbabwe Amongst Sexually Active Adolescent Girls and Women: Secondary Analysis of Zimbabwe Demographic Health Survey Data. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-314068/v1 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Medley, A.; Tsiouris, F.; Pals, S.; Senyana, B.; Hanene, S.; Kayeye, S.; Casquete, R.R.; Lasry, A.; Braaten, M.; Aholou, T. An Evaluation of an Enhanced Model of Integrating Family Planning into HIV Treatment Services in Zambia, April 2018–June 2019. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2023, 92, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duma, S.E.; Ngala, L.C. Nurses’ practice of integration of HIV prevention and sexual and reproductive health services in Ntcheu District, Malawi. Curationis 2019, 42, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, J.N.; Green, M.; Weaver, M.A.; Mpangile, G.; Kohi, T.W.; Mujaya, S.N.; Lasway, C. Integrating family planning services into HIV care and treatment clinics in Tanzania: Evaluation of a facilitated referral model. Health Policy Plan. 2014, 29, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfim, E.; Mupueleque, M.A.; Dos Santos, D.M.M.; Abdirazak, A.; de Arminda Bernardo, R.; Zakus, D.; Pires, P.H.d.N.M.; Siemens, R.; Belo, C.F. Quality assessment in primary health care: Adolescent and Youth Friendly Service, a Mozambican case study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 37, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khotle, J.T. Experiences of Nurses Initiating and Managing Human Immune-Deficiency Virus Infected Patients on Antiretroviral Treatment in Tshwane Clinics; University of Pretoria: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kanyangarara, M.; Sakyi, K.; Laar, A. Availability of integrated family planning services in HIV care and support sites in sub-Saharan Africa: A secondary analysis of national health facility surveys. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milford, C.; Scorgie, F.; Rambally Greener, L.; Mabude, Z.; Beksinska, M.; Harrison, A.; Smit, J. Developing a model for integrating sexual and reproductive health services with HIV prevention and care in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachale, F.; Mahaka, I.; Mhuriro, F.; Mugambi, M.; Murungu, J.; Ncube, B.; Ncube, G.; Ndwiga, A.; Nyirenda, R.; Otindo, V. Integration of HIV prevention and sexual and reproductive health in the era of anti-retroviral-based prevention: Findings from assessments in Kenya, Malawi and Zimbabwe. Gates Open Res. 2022, 5, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heffron, R.; Palanee-Phillips, T. Integration of HIV Prevention with Sexual and Reproductive Health Services; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silumbwe, A.; Nkole, T.; Munakampe, M.N.; Milford, C.; Cordero, J.P.; Kriel, Y.; Zulu, J.M.; Steyn, P.S. Community and health systems barriers and enablers to family planning and contraceptive services provision and use in Kabwe District, Zambia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastment, M.C.; Wanje, G.; Richardson, B.A.; Nassir, F.; Mwaringa, E.; Barnabas, R.V.; Sherr, K.; Mandaliya, K.; Jaoko, W.; McClelland, R.S. Performance of family planning clinics in conducting recommended HIV counseling and testing in Mombasa County, Kenya: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, G.; Beima-Sofie, K.M.; Roche, S.D.; Rousseau, E.; Travill, D.; Omollo, V.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Bekker, L.-G.; Bukusi, E.A.; Kinuthia, J. Health care providers as agents of change: Integrating PrEP with other sexual and reproductive health services for adolescent girls and young women. Front. Reprod. Health 2021, 3, 668672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumuza, S.E.; Rujumba, J.; Nkoyooyo, A.; Byaruhanga, R.; Wanyenze, R.K. Challenges encountered in providing integrated HIV, antenatal and postnatal care services: A case study of Katakwi and Mubende districts in Uganda. Reprod. Health 2016, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obure, C.D.; Sweeney, S.; Darsamo, V.; Michaels-Igbokwe, C.; Guinness, L.; Terris-Prestholt, F.; Muketo, E.; Nhlabatsi, Z.; Initiative, I.; Warren, C.E. The costs of delivering integrated HIV and sexual reproductive health services in limited resource settings. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.J.; Manalili, K.; Jolley, R.J.; Zelinsky, S.; Quan, H.; Lu, M. How to practice person-centred care: A conceptual framework. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milio, N. A framework for prevention: Changing health-damaging to health-generating life patterns. Am. J. Public Health 1976, 66, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donabedian, A. The quality of care: How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988, 260, 1743–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandage, R.V.; Mantha, S.S.; Rane, S.B. Strategy development using TOWS matrix for international project risk management based on prioritization of risk categories. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 12, 1003–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E.K.; Bunger, A.C.; Lengnick-Hall, R.; Gerke, D.R.; Martin, J.K.; Phillips, R.J.; Swanson, J.C. Ten years of implementation outcomes research: A scoping review. Implement. Sci. 2023, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukwevho, N. Teen Pregnancy and HIV Infections Plague Vhembe. Available online: https://health-e.org.za/2018/10/19/teen-pregnancy-and-hiv-infections-plague-vhembe/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Mulaudzi, V. Utilsation of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Rural South Africa: Knowledge, Perceptions and Experiences of Youths in Mutale Village in Limpopo Province; Sol Plaatje University: Kimberley, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bintabara, D.; Nakamura, K.; Seino, K. Determinants of facility readiness for integration of family planning with HIV testing and counseling services: Evidence from the Tanzania service provision assessment survey, 2014–2015. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalepa, T.N. The role of community health nurses in promoting school learners’ reproductive health in North West province. Health SA Gesondheid 2023, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, N.J.; Rasberry, C.; Liddon, N.; Szucs, L.E.; Johns, M.; Leonard, S.; Goss, S.J.; Oglesby, H. Addressing HIV/sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy prevention through schools: An approach for strengthening education, health services, and school environments that promote adolescent sexual health and well-being. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasberry, C.N.; Liddon, N.; Adkins, S.H.; Lesesne, C.A.; Hebert, A.; Kroupa, E.; Rose, I.D.; Morris, E. The importance of school staff referrals and follow-up in connecting high school students to HIV and STD testing. J. Sch. Nurs. 2017, 33, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuningsih, D. Increased Ability of Legal Solution in the Prevention of Promiscuous Sex Outside of Marriage. JL Pol’y Glob. 2023, 128, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, M.M.; Agbla, S.C.; Joy, M.; Aneja, K.; Pillinger, M.; Case, A.; Erondu, N.A.; Erkkola, T.; Graeden, E. Law, criminalisation and HIV in the world: Have countries that criminalise achieved more or less successful pandemic response? BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breckenridge, J.; Suchting, M.; Hanna-Osborne, S.; Porteous, J. Engaging with Victims and Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse: A Practice Guide for Workers and Organisations; National Office for Child Safety: Canberra, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey, J.G.; Havey, J.; Miles, G.M.; Channtha, N.; Vanntheary, L. “I Want Justice from People Who Did Bad Things to Children”: Experiences of Justice for Sex Trafficking Survivors. Dign. A J. Anal. Exploit. Violence 2021, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadhi, B.; Mboya, B.; Temu, F.; Ngware, Z. Assessing the need and capacity for integration of Family Planning and HIV counseling and testing in Tanzania. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2012, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mutambo, C.; Hlongwana, K. Healthcare workers’ perspectives on the barriers to providing HIV services to children in sub-saharan Africa. AIDS Res. Treat. 2019, 2019, 8056382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chola, M.; Hlongwana, K.; Ginindza, T.G. Understanding adolescent girls’ experiences with accessing and using contraceptives in Zambia. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloi, P.T.; Malapela, R.G. Adolescent girls’ perceptions regarding the use of contraceptives in Ekurhuleni District, Gauteng. Health SA Gesondheid 2024, 29, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhumba, S.K.; Mhando, N.E. Ubuntu ethics as a paradigm for human development in Africa. In The Palgrave Handbook of Ubuntu, Inequality and Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mutisya, R.; Wambua, J.; Nyachae, P.; Kamau, M.; Karnad, S.R.; Kabue, M. Strengthening integration of family planning with HIV/AIDS and other services: Experience from three Kenyan cities. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Political Factors

| Economic Factors

| Implications for programme goals

|

Social Factors

| Technological Factors

| Implications for programme goals

|

Strengths

| Weakness

|

Opportunities

| Threats

|

| Proposed Interventions | Programme Goals | Planned Activities | Indicator Targets | Responsible Stakeholders | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incorporation of Ubuntu principles and values into HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention service. | Implementing HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services that address adolescents’ health disparities and improve their sexual health outcomes through mutual care and interconnectedness with the providers. | Strengthening community involvement and empathetic communication for healthcare providers can create trust and encourage young people to seek necessary care without fear of judgment. | 10% of Ubuntu trained nurses per facility. | Ubuntu trained HIV, STIs, and pregnancy prevention healthcare providers. | Reduced stigma associated with HIV PrEP, Condom and Contraceptive use. Improved health outcomes for adolescents. |

| Competent integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention workforce. | Ensure universal service delivery and access to quality sexual and reproductive healthcare services. | Provide integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention training for healthcare providers in remote and underserved areas. Increasing workforce knowledge and skills related to HIV, STIs, and pregnancy prevention through e-learning (Department of Health Knowledge Hub platform). | 10% of AYFS-certified nurses per facility 10% of PrEP-certified nurses per facility 10% of PEP-certified nurses per facility. | District sexual and reproductive health coordinators. | Improved quality of HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services. |

| Integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention community-based training and engagement. | Assisting community members and adolescents, retaining knowledge, acquiring skills, and preparing for a quality future life. | Providing comprehensive (HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention) education and outreach programs and partnerships with local organizations to empower adolescents to make informed decisions about their sexual and reproductive health. Expanding mobile health clinics to reach remote areas and underserved communities. | 4 Community-outreach campaigns conducted per month. | Health Service Providers and Vhembe District supporting partners (NGOs). | Reduced prevalence of cases of HIV, STIs and teenage pregnancy due to a sexually healthy lifestyle. |

| Integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention community-school referral systems. | To bridge the gap between community, local schools and health services, allowing for better communication and coordination. | Support and train schoolteachers and community stakeholders to identify adolescents at risk of HIV, STI and pregnancy and refer them to the linked facility. | 4 School-outreach campaigns conducted per month. | School teachers, community stakeholders and healthcare providers. | Reduced prevalence of cases of HIV, STIs and teenage pregnancy at Vhembe District schools. |

| Establishment of integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention clinical governance committee. | Ensure staff compliance with global standards and policies relating to HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services. | Developing strategies to improve access to and quality HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services. | 4 Quality improvement plans on dual-method uptake. | District sexual and reproductive health coordinators. | Improved access to quality HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services. |

| Enhanced monitoring and evaluation of integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services. | Achieve the HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention indicator targets. | Measure the impact of the interventions, identify improvement areas, and ensure sustainability accountability. | 90% PrEP/PEP initiation rate per adolescent visits headcount. | Monitoring and evaluation of trained health providers. | Improved quality of services offered. |

| Variables | Frequencies N = 35 | Percentages % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Males Females | 26 9 | 74.3 25.7 |

| Participant Group | ||

| Healthcare Providers Community Leaders School Principals Parent/Guardian Adolescents Researchers | 12 3 3 7 6 4 | 34.3 8.6 8.6 20 17.1 11.4 |

| Age Group | ||

| 15–19 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 60-above | 6 4 16 5 3 1 | 17.1 11.4 45.7 14.3 8.6 2.9 |

| Statements | Response (N = 35) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Comments | |

| Feasibility: Is the proposed programme suitable? Is there practicality toward implementation? | 33 (94.3) | 2 (5.7) | A lack of transportation in the Department of Health is preventing healthcare providers from reaching the intended population through community outreach and school health programs. Once this issue has been resolved, all will be in place to reach the intended population. |

| Accessibility: Is the programme agreeable amongst the stakeholders? | 33 (94.3) | 2 (5.7) | To ensure human rights protection for adolescents, SAPS services should be integrated into HIV, STI, and teenage pregnancy prevention programs. |

| Appropriateness: Considering the setting and target audience, is the programme relevant? | 33 (94.3) | 2 (5.7) | Due to the lack of accountability for those infecting and impregnating teenagers, the root cause is not addressed holistically. Therefore, NDoH should collaborate with SAPS to conduct a thorough investigation and ensure justice. |

| Adoption: Is there an intention to adopt the developed programme? | 32 (91.4) | 3 (8.6) | MEC of Health should regularly conduct unannounced visits to rural clinics where there is high teenage pregnancy and new HIV infections to ensure the quality of healthcare services are provided. This will help to identify any area that requires improvement, and healthcare providers will ensure accountability for their actions. |

| Coverage: Is the desired population eligible to receive and benefit from the programme? | 34 (97.1) | 1 (2.9) | The SAPS should be notified about all teenagers under 16 years who have been impregnated and infected with HIV by any person above 16 years old. A parent should open the case, and a teenager should be referred by a nurse or social worker for further investigation. |

| Fidelity: Will the intervention be delivered as intended? | 29(82.9) | 6 (17.1) | The challenge will be the severe shortage of staff where passionate nurses will find it hard to implement the proposed interventions due to the abnormal staff ratio at our clinics. |

| Sustainability: Are the programme interventions sustainable? | 31 (88.6) | 4 (11.4) | The majority of nurses in our clinic are older, which makes it difficult to implement the proposed framework for improving the nurse-patient relationship; we need more nurses who are younger, friendly and approachable by youth. |

| Proposed Interventions | Programme Goals | Planned Activities | Indicator Targets | Responsible Stakeholders | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incorporation of Ubuntu principles and values into HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention service. | Implementing HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services that address adolescents’ health disparities and improve their sexual health outcomes through mutual care and interconnectedness with the providers. | Strengthening community involvement and empathetic communication for healthcare providers can create trust and encourage young people to seek necessary care without fear of judgment. | 10% of Ubuntu trained nurses per facility. | Ubuntu trained HIV, STIs, and pregnancy prevention healthcare providers. | Reduced stigma associated with HIV PrEP, Condom and Contraceptive use. Improved sexual and reproductive health outcomes for adolescents. |

| Competent integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention workforce. | Ensure universal service delivery and access to quality sexual and reproductive healthcare services. | Provide integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention training for healthcare providers in remote and underserved areas. Increasing workforce knowledge and skills related to HIV, STIs, and pregnancy prevention through e-learning (Department of Health Knowledge Hub platform). | 10% of AYFS-certified nurses per facility 10% of PrEP-certified nurses per facility 10% of PEP-certified nurses per facility. | District sexual and reproductive health coordinators. | Improved quality of HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services across all the facilities. |

| Integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention community-based training and engagement. | Assisting community members and adolescents, retaining knowledge, acquiring skills, and preparing for a quality future life. | Adolescents can be empowered to make informed decisions about their sexual and reproductive health through comprehensive education and outreach programs, as well as the establishment of partnerships with local organizations. Furthermore, expanding mobile health clinics can help reach remote areas and underserved populations. | 4 Community-outreach campaigns conducted per month. | Health Service Providers and Vhembe District supporting partners (NGOs). | Reduced prevalence of cases of HIV, STIs and teenage pregnancy due to a sexually healthy lifestyle. |

| Integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention community-school referral systems. | To bridge the gap between community, local schools and health services, allowing for better communication and coordination. | Support and train schoolteachers and community stakeholders to identify adolescents at risk of HIV, STI and pregnancy and refer them to the linked facility. | 4 School-outreach campaigns conducted per month. | School teachers, community stakeholders and healthcare providers. | Reduced prevalence of cases of HIV, STIs and teenage pregnancy at Vhembe District schools. |

| Establishment of integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention clinical governance committee. | Ensure staff compliance with global standards and policies relating to HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services. | Developing strategies to improve access to and quality HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services. | 4 Quality improvement plans on dual-method uptake. | District sexual and reproductive health coordinators. | Improved access to quality HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services. |

| Enhanced monitoring and evaluation of integrated HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention services. | Achieve the HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention indicator targets. | Measure the impact of the interventions, identify improvement areas, and ensure sustainability accountability. | 90% PrEP/PEP initiation rate per adolescent visits headcount. | Monitoring and evaluation of trained health providers. | Improved quality of services offered. |

| Establishment of a Risk Committee in each community to address teenage pregnancy and HIV. | To identify, assess, and manage the risks of HIV and pregnancy among adolescents and build healthier and safer environments for teens. | The Risk Committee assesses the community’s risks and develops strategies to mitigate those risks. They should also create an emergency plan and ensure all stakeholders are aware of it and prepared to act if needed. | 90% adolescents referred to the clinic for HIV/STI screening and PrEP/PEP initiation per referred total headcount. | Parents, teachers, healthcare providers, community leaders, local businesses, law enforcement, and other stakeholders. | Safe environment/community that reduces HIV, STIs, and teenage pregnancy. |

| Enhanced reporting system between clinics and SAPS for children under the age of 16 infected with HIV or impregnated by an adult using form 22 (see Supplementary File). | Ensure that teenagers are protected, and they receive the care and support they need. | District program coordinators to provide support and training to healthcare providers, social workers, teachers and parents of teenagers regarding the process flow for reporting statutory rape for further investigation of any teenager impregnated or infected with HIV by an adult. | 90% of all adolescents under the age of 16 infected with HIV or impregnated by adults referred to the nearest SAPS for further investigation. | Parents, teachers, healthcare providers, community leaders, law enforcement, and other stakeholders. | Reduced prevalence of cases of HIV, STIs and teenage pregnancy at Vhembe District local communities. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rammela, M.; Makhado, L. Development and Validation of an Integrated HIV/STI, and Pregnancy Prevention Programme: Improving Adolescent Sexual Health Outcomes. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10090273

Rammela M, Makhado L. Development and Validation of an Integrated HIV/STI, and Pregnancy Prevention Programme: Improving Adolescent Sexual Health Outcomes. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(9):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10090273

Chicago/Turabian StyleRammela, Mukovhe, and Lufuno Makhado. 2025. "Development and Validation of an Integrated HIV/STI, and Pregnancy Prevention Programme: Improving Adolescent Sexual Health Outcomes" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 9: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10090273

APA StyleRammela, M., & Makhado, L. (2025). Development and Validation of an Integrated HIV/STI, and Pregnancy Prevention Programme: Improving Adolescent Sexual Health Outcomes. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(9), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10090273