18-Fluorine-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Computer Tomography Imaging in Melioidosis: Valuable but Not Essential

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

- 1.

- Two 18-F FDG PET/CT scans performed for pyrexia of unknown origin (9.5%);

- 2.

- Twelve 18-F FDG PET/CT scans for ascertaining the extent of dissemination of melioidosis (57.1%);

- 3.

- Five 18-F FDG PET/CT scans for monitoring the response to treatment of known foci (23.8%);

- 4.

- Five 18-F FDG PET/CT scans for suspected or known malignancy (23.8%).

- 1.

- Pyrexia of unknown origin 2/2 (100%);

- 2.

- The extent of dissemination of melioidosis 3/12 (25%);

- 3.

- The monitoring response to the treatment of known foci 5/5 (100%);

- 4.

- Suspected or known malignancy 3/5 (60%).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| FDG | Fluorodeoxyglucose |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| US | Ultrasound |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| TEVAR | Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair |

Appendix A

| Demographics and Comorbidities | Clinical Scenario | Indication Category | 18-F FDG PET/CT Result | Change in Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 69F T2DM, CKD, IHD, asthma | Previous pulmonary melioidosis, represented with concurrent breast cancer and B. pseudomallei breast abscess | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination AND suspected/known malignancy | 1st PET: Study identified breast lesion with no disseminated or metastatic disease | 1st PET: Did not change management of melioidosis 1st PET: Guided oncological management approach |

| 2. 56F T2DM | Disseminated melioidosis with pulmonary, splenic, liver, peripancreatic and widespread upper and lower limb osteomyelitis with multiple septic joints | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination 2nd PET: Monitoring response to treatment | 1st PET: Identified extent of infection but did not add to previous MRI results 2nd PET: Performed 9 months later; showed resolution of PET avidity | 1st PET: Did not change management over clinical examination and MRI findings 2nd PET: Gave treating clinicians confidence to cease treatment despite ongoing pain thought to be due to mechanical arthritis |

| 3. 81M Myelodysplastic syndrome, CKD, IHD | Initially thought to be B. pseudomallei bacteraemia with no focus as it had unremarkable CT CAP results | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination | 1st PET: Multiple FDG avid nodules in lung, mediastinum and duodenum | 1st PET: Identified pulmonary involvement not seen on CT 2 weeks earlier, altering duration of IV intensive phase of therapy |

| 4. 73F T2DM, asthma/COPD, cognitive impairment | Presented 1 month prior to diagnosis of melioidosis with pneumonia and lung lesion, improved and discharged home, PET ordered for malignancy investigation given persistent lung lesion; represented following PET with respiratory sepsis | 1st PET: Suspected/known malignancy | 1st PET: Partially cystic lung lesion thought unlikely to be malignant; no metastatic or disseminated disease | 1st PET: Did not change management compared to conventional imaging |

| 5. 42M Asthma Fibula ORIF | Disseminated melioidosis with pulmonary splenic and prostatic and cutaneous abscesses Clinical concern for infected metalware at ORIF site | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination | 1st PET: PET performed 2 months after diagnosis; showed active prostate infection, no other foci of infection | 1st PET: Did not change management compared to conventional imaging and clinical impression. |

| 6. 31F T2DM, RHD | Disseminated melioidosis with preceding pyrexia of unknown origin; presented with back pain and rising melioidosis serology titre; subcarinal lymphadenopathy identified on CT | 1st PET: Pyrexia of unknown origin | 1st PET: Identified multiple nodal, splenic and small bowel foci | 1st PET: Prompted lymph node biopsy; identified small bowel and splenic FDG avid lesions that were not identified on CT or abdominal ultrasound; guided duration of IV intensive therapy |

| 7. 29F Hazardous alcohol use | Disseminated melioidosis with bacteraemia, scalp and extradural abscess | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination | 1st PET: Large left temporal melioidosis site and few subcutaneous and cervical nodularities; no distant foci | 1st PET: Did not change management of conventional imaging with CT and MRI |

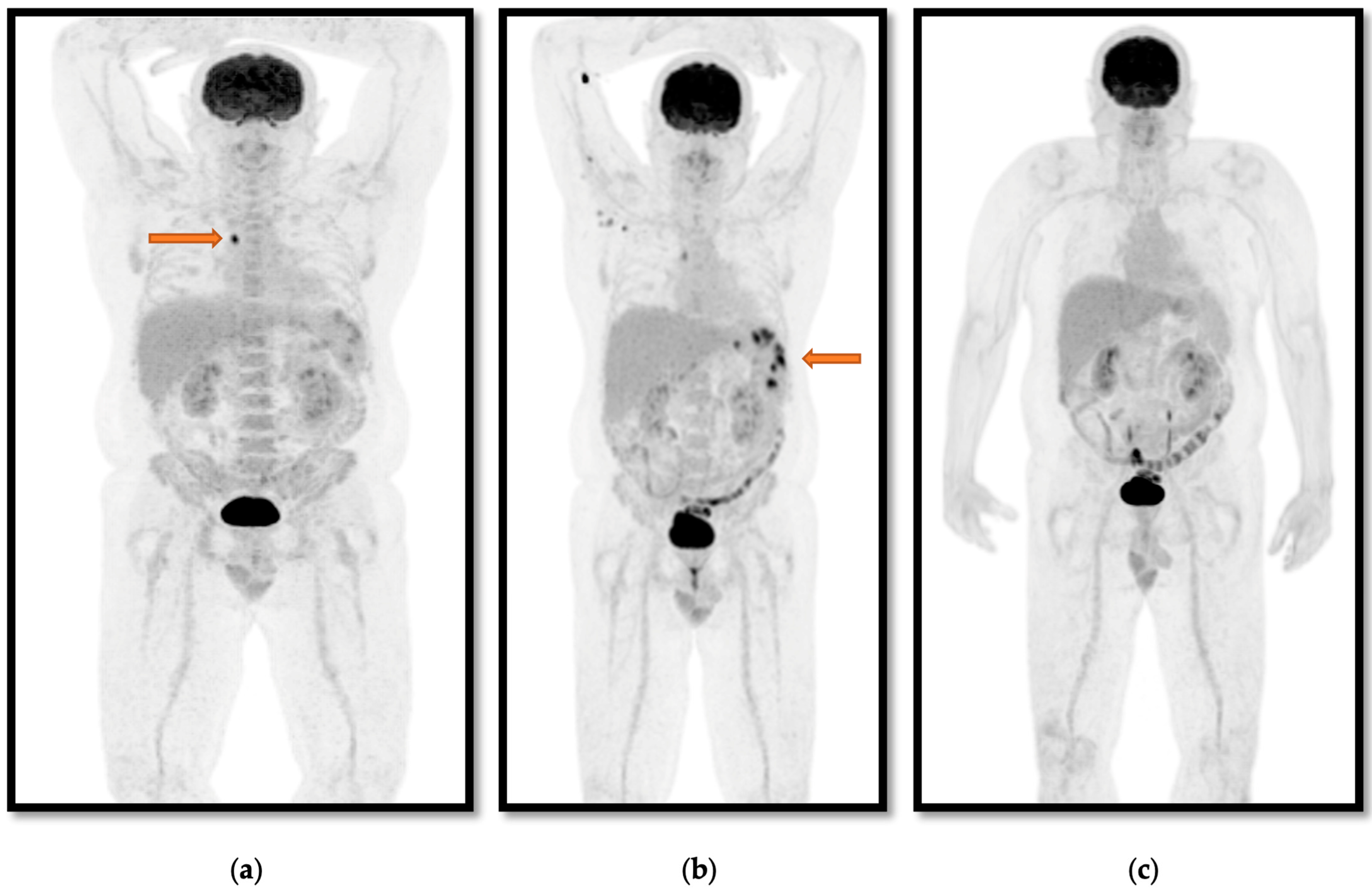

| 8. 50M T2DM, hazardous alcohol use | Disseminated melioidosis with splenic hepatic and nodal foci; presented with pyrexia of unknown origin, arthralgia and abdominal pain; CT findings of disseminated lesions concerning for metastatic malignancy | 1st PET: Pyrexia of unknown origin AND suspected/confirmed malignancy 2nd PET: Monitoring response to treatment 3rd PET: Monitoring response to treatment | 1st PET: FDG avid paratracheal lymphadenopathy and splenic foci 2nd PET: New axillary FDG avid axillary lymph nodes and increased avidity of known splenic foci 3rd PET: No positive foci of infection identified | 1st PET: Identified new foci which guided biopsy, leading to diagnosis of melioidosis 2nd PET: Prompted extension of IV intensive phase from 4 weeks to total of 12 weeks due to increasing SUVmax of splenic foci at 3.5 weeks of IV therapy; CT performed prior to PET showed that these lesions were volumetrically unchanged 3rd PET: Gave clinicians confidence to cease antibiotics at planned duration despite ongoing non-specific symptoms |

| 9. 68M T2DM | Concurrent melioidosis and tuberculosis diagnosed after positive PET and lymph node biopsy performed during investigation for hoarse voice initially presumed to be due to cancer | 1st PET: Suspected/confirmed malignancy | 1st PET: Low-grade mediastinal and cervical lymphadenopathy | 1st PET: Identified foci were limited to lymphadenitis in mediastinum and cervical lymph nodes guiding duration of therapy |

| 10. 49M CKD3b, urethral stricture, COPD, latent TB, chronic hepatitis B, right AKA due to previous necrotising fasciitis, anal SCC in remission | Disseminated melioidosis with osteomyelitis, prostatic and cutaneous foci; relapsed 18 months later with prostatic, splenic and hepatic abscesses | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination | 1st PET: Identified prostatic, ischial, stomach and colonic foci | 1st PET: Identified bony FDG avidity suggestive of osteomyelitis not previously identified on other imaging, which guided planned duration, but duration extended beyond this due to persistently positive urine cultures |

| 11. 65F T1DM, HFrEF, pulmonary HTN | Pulmonary melioidosis with incomplete eradication phase; relapse representation 4 months later with 1st PET performed at that time and 2nd performed 6 weeks later | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination 2nd PET: Monitoring response to treatment | 1st PET: Bilateral pulmonary and mediastinal nodal foci; identified nonspecific uptake in small bowel 2nd PET: Near resolution of pulmonary and mediastinal foci; resolution of small bowel focus | 1st PET: Did not change management compared to chest CT 2nd PET: Gave clinicians confidence to transition to oral eradication phase therapy given previous relapse |

| 12. 45F T2DM, asthma/COPD | Pulmonary melioidosis with pleural effusion; delay in isolating B. pseudomallei with multiple courses of ineffective antibiotics | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination | 1st PET: No hypermetabolic findings to suggest active melioidosis | 1st PET: Did not change management over CT |

| 13. 66M T2DM, CKD3a, multiple myeloma | Pulmonary melioidosis concurrent with active treatment with lenalidomide for multiple myeloma | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination AND suspected/known malignancy | 1st PET: Multiple hypermetabolic lesions in mediastinal lymph nodes and skeleton | 1st PET: Did not change management compared to CT |

| 14. 71M Hazardous alcohol use, CP-A cirrhosis | Cutaneous melioidosis with dissemination and subsequent osteomyelitis | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination | 1st PET: Active soft tissue and possible osteomyelitis | 1st PET: Did not change management compared to CT; MRI was only modality that clearly showed evidence of osteomyelitis |

| 15. 65M No comorbidities | Underwent TEVAR for penetrating thoracic aortic ulcer 10 days prior to diagnosis of bacteraemic melioidosis after representing febrile | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination 2nd PET: Monitoring response to treatment | 1st PET: Active infection with paraortic and retrocrural collections 2nd PET: Complete metabolic response to antibiotic therapy | 1st PET: Confirmed clinical suspicion of graft infection not identified on CT 2nd PET: Complete resolution of metabolic changes while on lifelong suppressive cotrimoxazole, suggesting adequate suppression |

| 16. 71F Bronchiectasis | Pulmonary melioidosis after presenting with 6-month history of productive cough | 1st PET: Extent of dissemination | 1st PET: No hypermetabolic active foci of infection | 1st PET: Did not change management of melioidosis compared to CT |

References

- Wiersinga, W.J.; Virk, H.S.; Torres, A.G.; Currie, B.J.; Peacock, S.J.; Dance, D.A.; Limmathurotsakul, D. Melioidosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 17107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, B.J.; Mayo, M.; Ward, L.M.; Kaestli, M.; Meumann, E.M.; Webb, J.R.; Woerle, C.; Baird, R.W.; Price, R.N.; Marshall, C.S.; et al. The Darwin Prospective Melioidosis Study: A 30-year prospective, observational investigation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, B.J. Melioidosis: Evolving concepts in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 36, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnie, E.; Virk, H.S.; Savelkoel, J.; Spijker, R.; Bertherat, E.; Dance, D.A.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Haagsma, J.A.; Wiersinga, W.J. Global burden of melioidosis in 2015: A systematic review and data synthesis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, G.; Lancellotti, P.; Antunes, M.J.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Casalta, J.P.; Del Zotti, F.; Dulgheru, R.; El Khoury, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3075–3128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kung, B.T.; Seraj, S.M.; Zadeh, M.Z.; Rojulpote, C.; Kothekar, E.; Ayubcha, C.; Ng, K.S.; Ng, K.K.; Au-Yong, T.K.; Werner, T.J.; et al. An update on the role of 18F-FDG-PET/CT in major infectious and inflammatory diseases. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 9, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van der Vaart, T.W.; Fowler, V.G. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: Worth the wait? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 1361–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanem-Zoubi, N.; Kagna, O.; Abu-Elhija, J.; Mustafa-Hellou, M.; Qasum, M.; Keidar, Z.; Paul, M. Integration of FDG-PET/CT in the Diagnostic Workup for Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia: A Prospective Interventional Matched-cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e3859–e3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.; Glaudemans, A.W.; Touw, D.J.; van Melle, J.P.; Willems, T.P.; Maass, A.H.; Natour, E.; Prakken, N.H.; Borra, R.J.; van Geel, P.P.; et al. Diagnostic value of imaging in infective endocarditis: A systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e1–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauri, C.; Signore, A.; Glaudemans, A.W.; Treglia, G.; Gheysens, O.; Slart, R.H.; Iezzi, R.; Prakken, N.H.; Debus, E.S.; Honig, S.; et al. Evidence-based guideline of the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) on imaging infection in vascular grafts. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 3430–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subran, B.; Ackermann, F.; Watin-Augouard, L.; Rammaert, B.; Rivoisy, C.; Vilain, D.; Canzi, A.M.; Kahn, J.E. Melioidosis in a European traveler without comorbidities: A case report and literature review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, e781–e783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, P.; Shelley, S.; Elangoven, I.M.; Jaykanth, A.; Ejaz, A.P.; Rao, N.S. 18-Fluorine-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography in the Evaluation of the Great Masquerader Melioidosis: A Case Series. Indian J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 35, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayub, I.I.; Thangaswamy, D.; Krishna, V.; Sridharan, K.S. Role for Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography in Melioidosis. Indian J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 36, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaw, K.K.; Wasgewatta, S.L.; Kwong, K.K.; Fielding, D.; Heraganahally, S.S.; Currie, B.J. Chronic Pulmonary Melioidosis Masquerading as lung malignancy diagnosed by EBUS guided sheath technique. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2019, 28, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Yap, A.; Wu, E.; Yap, J. A mimic of bronchogenic carcinoma—Pulmonary melioidosis. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 29, 101006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, R.P.; Marshall, C.S.; Anstey, N.M.; Ward, L.; Currie, B.J. 2020 Review and revision of the 2015 Darwin melioidosis treatment guideline; paradigm drift not shift. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, B.J.; Meumann, E.M.; Kaestli, M. The Expanding Global Footprint of Burkholderia pseudomallei and Melioidosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2023, 108, 1081–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bramwell, J.; Kovaleva, N.; Morigi, J.J.; Currie, B.J. 18-Fluorine-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Computer Tomography Imaging in Melioidosis: Valuable but Not Essential. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030069

Bramwell J, Kovaleva N, Morigi JJ, Currie BJ. 18-Fluorine-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Computer Tomography Imaging in Melioidosis: Valuable but Not Essential. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(3):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030069

Chicago/Turabian StyleBramwell, Joshua, Natalia Kovaleva, Joshua J. Morigi, and Bart J. Currie. 2025. "18-Fluorine-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Computer Tomography Imaging in Melioidosis: Valuable but Not Essential" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 3: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030069

APA StyleBramwell, J., Kovaleva, N., Morigi, J. J., & Currie, B. J. (2025). 18-Fluorine-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Computer Tomography Imaging in Melioidosis: Valuable but Not Essential. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(3), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030069