Respiratory Illness and Diarrheal Disease Surveillance in U.S. Military Personnel Deployed to Southeast Asia for Military Exercises from 2023–2025

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Molecular Testing

2.3. Viral Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS)

2.4. Culture Isolation and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

2.5. Data Analysis and Reporting

3. Results

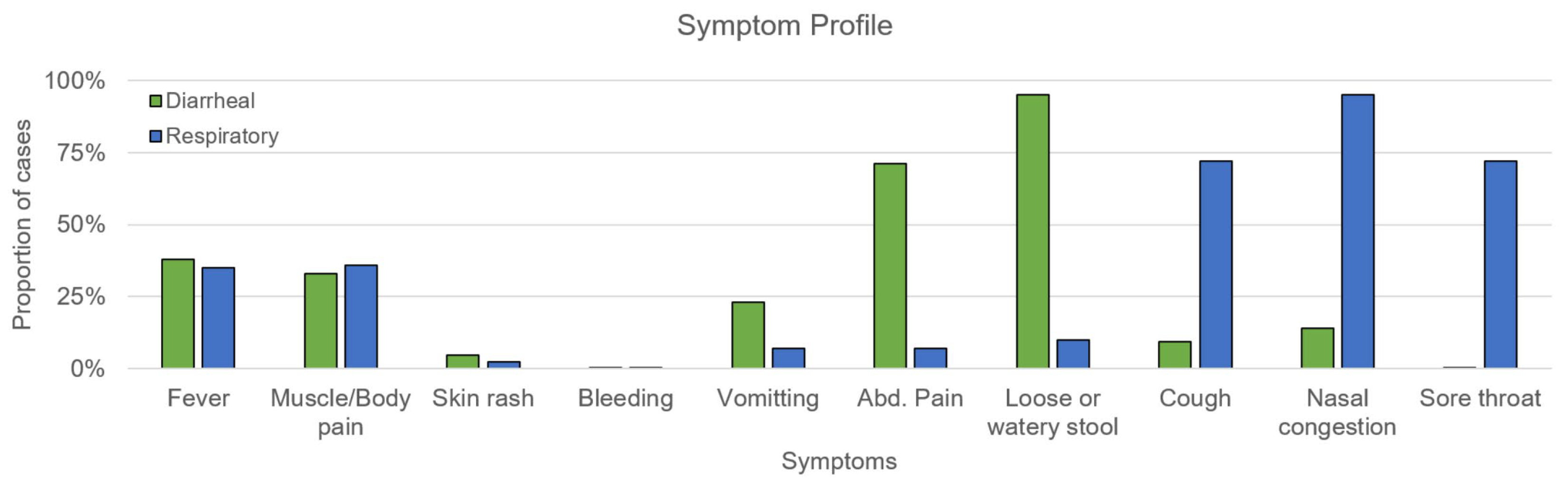

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Findings

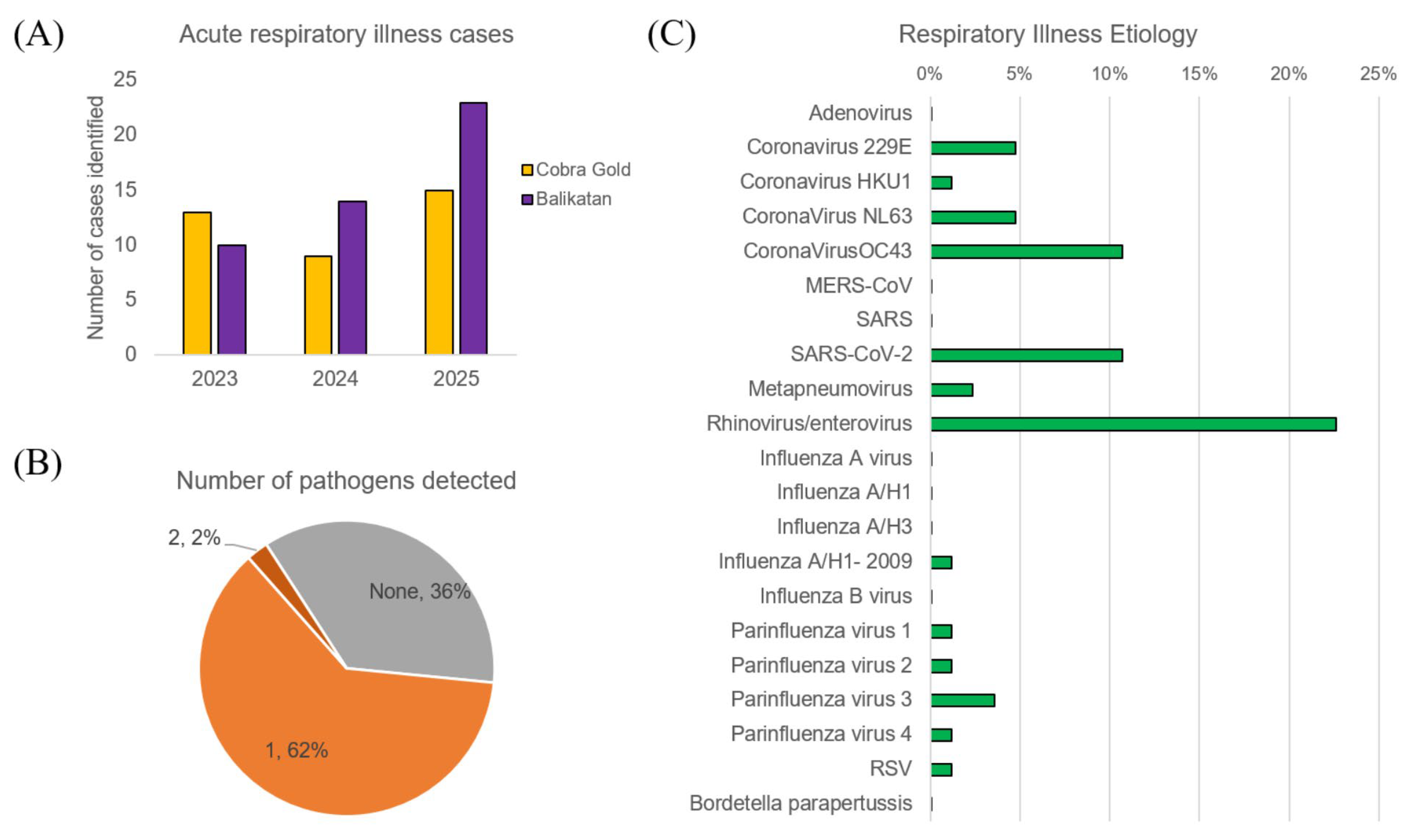

3.2. Respiratory Illness Etiology

3.3. Diarrheal Disease Etiology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| HCP | Healthcare Provider |

| EPEC | Enteropathogenic E. col |

| EIEC | Enteroinvasive E. coli |

| EAEC | Enteroaggregative E. coli |

| ETEC | Enterotoxigenic E. coli |

| STEC | Shiga toxin-producing E. coli |

| AMP | ampicillin |

| AXM | azithromycin |

| CIP | ciprofloxacin |

| NAL | nalidixic acid |

| SXT | trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| CAZ | ceftazidime |

| CRO | ceftriaxone |

| CTX | cefotaxime |

| TE | tetracycline |

| IMP | imipenem |

| MEM | meropenem |

| ERY | erythromycin |

| RSV | respiratory syncytial viral |

| NPA | nasopharyngeal |

| AST | Antimicrobial susceptibility testing |

| CG | Cobra Gold |

| BK | Balikatan |

| WRAIR | Walter Reed Army Institute of Research |

| WRAIR-AFRIMS | Walter Reed Army Institute of Research—Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences |

References

- Newman, E.N.; Johnstone, P.; Bridge, H.; Wright, D.; Jameson, L.; Bosworth, A.; Hatch, R.; Hayward-Karlsson, J.; Osborne, J.; Bailey, M.S.; et al. Seroconversion for infectious pathogens among UK military personnel deployed to Afghanistan, 2008–2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 2015–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virchow, R. War typhus and dysentery. Chic. Med. Exam. 1871, 12, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coox, A.D. Valmy. Mil. Aff. 1948, 12, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R.V.; Streitz, M.; Babina, T.; Fried, J.R. Dengue and US military operations from the Spanish-American War through today. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byerly, C.R. Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic in the U.S. Army During World War I; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Beadle, C.; Hoffman, S.L. History of malaria in the United States Naval Forces at war: World War I through the Vietnam conflict. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1993, 16, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, J.A. Acute rheumatism in military history. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1946, 39, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanks, G.D. How World War 1 changed global attitudes to war and infectious diseases. Lancet 2014, 384, 1699–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, M.S.; Tribble, D.R.; Putnam, S.D.; Mostafa, M.; Brown, T.R.; Letizia, A.; Armstrong, A.W.; Sanders, J.W. Past trends and current status of self-reported incidence and impact of disease and nonbattle injury in military operations in Southwest Asia and the Middle East. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 2199–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.W.; Bhoomiboonchoo, P.; Simasathien, S.; Salje, H.; Huang, A.; Rangsin, R.; Jarman, R.G.; Fernandez, S.; Klungthong, C.; Hussem, K.; et al. Elevated transmission of upper respiratory illness among new recruits in military barracks in Thailand. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2015, 9, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.S.; Lustik, M.B.; Reichert-Scrivner, S.A.; Woodbury, R.L.; Jones, M.U.; Horseman, T.S. Respiratory Viral Pathogens Among U.S. Military Personnel at a Medical Treatment Facility in Hawaii From 2014 to 2019. Mil. Med. 2022, 187, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakonieczna, A.; Kwiatek, M.; Abramowicz, K.; Zawadzka, M.; Bany, I.; Glowacka, P.; Skuza, K.; Lepionka, T.; Szymanski, P. Assessment of the prevalence of respiratory pathogens and the level of immunity to respiratory viruses in soldiers and civilian military employees in Poland. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, R.N.; Cantrell, J.A.; Mallak, C.T.; Gaydos, J.C. Adenovirus-associated deaths in US military during postvaccination period, 1999–2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, J.M.; Hawksworth, A.W.; Blair, P.J.; Faix, D.J.; Raman, R.; Russell, K.L.; Gray, G.C. Dramatic decline of respiratory illness among US military recruits after the renewed use of adenovirus vaccines. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, K.L.; Hawksworth, A.W.; Ryan, M.A.; Strickler, J.; Irvine, M.; Hansen, C.J.; Gray, G.C.; Gaydos, J.C. Vaccine-preventable adenoviral respiratory illness in US military recruits, 1999–2004. Vaccine 2006, 24, 2835–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, S.; Erra, E.; Lundell, R.; Nyqvist, A.; Hepo-Oja, P.; Mannonen, L.; Jarva, H.; Loginov, R.; Lindh, E.; Lakoma, L.; et al. Adenovirus type 7d outbreak associated with severe clinical presentation, Finland, February to June 2024. Eurosurveillance 2025, 30, 2500061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizewski, R.A.; Sealfon, R.S.G.; Park, S.W.; Smith, G.R.; Porter, C.K.; Gonzalez-Reiche, A.S.; Ge, Y.; Miller, C.M.; Goforth, C.W.; Pincas, H.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak Dynamics in an Isolated US Military Recruit Training Center With Rigorous Prevention Measures. Epidemiology 2022, 33, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, M.R.; Geibe, J.R.; Sears, C.L.; Riegodedios, A.J.; Luse, T.; Von Thun, A.M.; McGinnis, M.B.; Olson, N.; Houskamp, D.; Fenequito, R.; et al. An Outbreak of Covid-19 on an Aircraft Carrier. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2417–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalani, T.; Maguire, J.D.; Grant, E.M.; Fraser, J.; Ganesan, A.; Johnson, M.D.; Deiss, R.G.; Riddle, M.S.; Burgess, T.; Tribble, D.R.; et al. Epidemiology and self-treatment of travelers’ diarrhea in a large, prospective cohort of department of defense beneficiaries. J. Travel Med. 2015, 22, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhidatta, L.; McDaniel, P.; Sornsakrin, S.; Srijan, A.; Serichantalergs, O.; Mason, C.J. Case-control study of diarrheal disease etiology in a remote rural area in Western Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 83, 1106–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kietsiri, P.; Sornsakrin, S.; Nou, S.; Oransathid, W.; Peerapongpaisarn, D.; Oransathid, W.; Nobthai, P.; Wassanarungroj, P.; Gonwong, S.; Sakpaisal, P.; et al. Understanding the etiology of diarrheal illness in Cambodia in a case-control study from 2020 to 2023. Gut Pathog. 2025, 17, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodhidatta, L.; Anuras, S.; Sornsakrin, S.; Suksawad, U.; Serichantalergs, O.; Srijan, A.; Sethabutr, O.; Mason, C.J. Epidemiology and etiology of Traveler’s diarrhea in Bangkok, Thailand, a case-control study. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2019, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lertsethtakarn, P.; Silapong, S.; Sakpaisal, P.; Serichantalergs, O.; Ruamsap, N.; Lurchachaiwong, W.; Anuras, S.; Platts-Mills, J.A.; Liu, J.; Houpt, E.R.; et al. Travelers’ Diarrhea in Thailand: A Quantitative Analysis Using TaqMan(R) Array Card. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, O.; Rapp, C.; Biale, L.; Imbert, I.; Lechevalier, D.; Banal, F. An uncommon triad. J. Travel Med. 2017, 24, tax047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, J.A.; Riddle, M.S.; Gormley, R.P.; Tribble, D.R.; Porter, C.K. The epidemiology of infectious gastroenteritis related reactive arthritis in U.S. military personnel: A case-control study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsuwanon, P.; Krairojananan, P.; Rodkvamtook, W.; Leepitakrat, S.; Davidson, S.; Wanja, E. Surveillance for Scrub Typhus, Rickettsial Diseases, and Leptospirosis in US and Multinational Military Training Exercise Cobra Gold Sites in Thailand. US Army Med. Dep. J. 2018, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mason, C.J.; Sornsakrin, S.; Seidman, J.C.; Srijan, A.; Serichantalergs, O.; Thongsen, N.; Ellis, M.W.; Ngauy, V.; Swierczewski, B.E.; Bodhidatta, L. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter and other diarrheal pathogens isolated from US military personnel deployed to Thailand in 2002–2004: A case-control study. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2017, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, J.; Hanley, K.; Schultz, R.; Lewis, M.; Freed, N.E.; Ellis, M.; Ngauy, V.; Stoebner, R.; Ryan, M.; Russell, K. Surveillance for febrile respiratory infections during Cobra Gold 2003. Mil. Med. 2006, 171, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krairojananan, P.; Wasuworawong, K.; Leepitakrat, S.; Monkanna, T.; Wanja, E.W.; Davidson, S.A.; Poole-Smith, B.K.; McCardle, P.W.; Mann, A.; Lindroth, E.J. Leptospirosis Risk Assessment in Rodent Populations and Environmental Reservoirs in Humanitarian Aid Settings in Thailand. Microorganisms 2024, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertsethtakarn, P.; Nakjarung, K.; Silapong, S.; Neesanant, P.; Sakpaisal, P.; Bodhidatta, L.; Liu, J.; Houpt, E.; Velasco, J.M.; Macareo, L.R.; et al. Detection of Diarrhea Etiology Among U.S. Military Personnel During Exercise Balikatan 2014, Philippines, Using TaqMan Array Cards. Mil. Med. 2016, 181, e1669–e1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, J.M.; Valderamat, M.T.; Nogrado, K.; Wongstitwilairoong, T.; Swierczewski, B.; Bodhidatta, L.; Lertsethtakarn, P.; Klungthong, C.; Fernandez, S.; Mason, C.; et al. Diarrheal and Respiratory Illness Surveillance During US-RP Balikatan 2014. MSMR 2015, 22, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, J.M.; Yoon, I.K.; Mason, C.J.; Jarman, R.G.; Bodhidatta, L.; Klungthong, C.; Silapong, S.; Valderama, M.T.; Wongstitwilairoong, T.; Torres, A.G.; et al. Applications of PCR (real-time and MassTag) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in diagnosis of respiratory infections and diarrheal illness among deployed U.S. military personnel during exercise Balikatan 2009, Philippines. Mil. Med. 2011, 176, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, G.J.; Zhen, W.; Smith, E.; Manji, R.; Silbert, S.; Lima, A.; Harington, A.; McKinley, K.; Kensinger, B.; Neff, C.; et al. Multicenter Evaluation of the BioFire Respiratory Panel 2.1 (RP2.1) for Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Nasopharyngeal Swab Samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e0006622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buss, S.N.; Leber, A.; Chapin, K.; Fey, P.D.; Bankowski, M.J.; Jones, M.K.; Rogatcheva, M.; Kanack, K.J.; Bourzac, K.M. Multicenter evaluation of the BioFire FilmArray gastrointestinal panel for etiologic diagnosis of infectious gastroenteritis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leber, A.L.; Everhart, K.; Daly, J.A.; Hopper, A.; Harrington, A.; Schreckenberger, P.; McKinley, K.; Jones, M.; Holmberg, K.; Kensinger, B. Multicenter Evaluation of BioFire FilmArray Respiratory Panel 2 for Detection of Viruses and Bacteria in Nasopharyngeal Swab Samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e01945-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, F.; Schmutz, S.; Gosert, R.; Huder, J.B.; Redli, P.M.; Capaul, R.; Hirsch, H.H.; Boni, J.; Zbinden, A. Usefulness of the GenMark ePlex RPP assay for the detection of respiratory viruses compared to the FTD21 multiplex RT-PCR. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 101, 115424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gratz, J.; Amour, C.; Kibiki, G.; Becker, S.; Janaki, L.; Verweij, J.J.; Taniuchi, M.; Sobuz, S.U.; Haque, R.; et al. A laboratory-developed TaqMan Array Card for simultaneous detection of 19 enteropathogens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, B. BBDuk: Adapter, Quality Trimming and Filtering. Available online: https://github.com/BioInfoTools/BBMap/blob/master/sh/bbduk.sh (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubaugh, N.D.; Gangavarapu, K.; Quick, J.; Matteson, N.L.; De Jesus, J.G.; Main, B.J.; Tan, A.L.; Paul, L.M.; Brackney, D.E.; Grewal, S.; et al. An amplicon-based sequencing framework for accurately measuring intrahost virus diversity using PrimalSeq and iVar. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brister, J.R.; Ako-Adjei, D.; Bao, Y.; Blinkova, O. NCBI viral genomes resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D571–D577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houpt, E.; Gratz, J.; Kosek, M.; Zaidi, A.K.; Qureshi, S.; Kang, G.; Babji, S.; Mason, C.; Bodhidatta, L.; Samie, A.; et al. Microbiologic methods utilized in the MAL-ED cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59 (Suppl. S4), S225–S232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- NARMS. NARMS Integrated Report. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/national-antimicrobial-resistance-monitoring-system/2015-narms-integrated-report (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Rammaert, B.; Goyet, S.; Tarantola, A.; Hem, S.; Rith, S.; Cheng, S.; Te, V.; Try, P.L.; Guillard, B.; Vong, S.; et al. Acute lower respiratory infections on lung sequelae in Cambodia, a neglected disease in highly tuberculosis-endemic country. Respir. Med. 2013, 107, 1625–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanlapakorn, N.; Thongpan, I.; Sarawanangkoor, N.; Vichaiwattana, P.; Auphimai, C.; Srimuan, D.; Thatsanathorn, T.; Kongkiattikul, L.; Kerr, S.J.; Poovorawan, Y. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of severe acute respiratory infections among hospitalized children under 5 years of age in a tertiary care center in Bangkok, Thailand, 2019–2020. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubaugh, N.D.; Ladner, J.T.; Lemey, P.; Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E.C.; Andersen, K.G. Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchard, M.A.; Lemey, P.; Baele, G.; Ayres, D.L.; Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. Bayesian phylogenetic and phylodynamic data integration using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, vey016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, A.; Martiny, D.; van Waterschoot, N.; Hallin, M.; Maniewski, U.; Bottieau, E.; Van Esbroeck, M.; Vlieghe, E.; Ombelet, S.; Vandenberg, O.; et al. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles among Campylobacter isolates obtained from international travelers between 2007 and 2014. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2101–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, J.N.; Eghnatios, E.; El Roz, A.; Fardoun, T.; Ghssein, G. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance and risk factors for campylobacteriosis in Lebanon. J. Infect. Dev. Countries 2019, 13, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribble, D.R. Antibiotic Therapy for Acute Watery Diarrhea and Dysentery. Mil. Med. 2017, 182, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S.T.; Gallagher, K.I.; Mullish, B.H.; Serrano-Contreras, J.I.; Alexander, J.L.; Miguens Blanco, J.; Danckert, N.P.; Valdivia-Garcia, M.; Hopkins, B.J.; Ghai, A.; et al. Rectal swabs as a viable alternative to faecal sampling for the analysis of gut microbiota functionality and composition. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Meydan, C.; Afshin, E.E.; Lili, L.N.; D’Adamo, C.R.; Rickard, N.; Dudley, J.T.; Price, N.D.; Zhang, B.; Mason, C.E. A Wipe-Based Stool Collection and Preservation Kit for Microbiome Community Profiling. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 889702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cobra Gold 2023–2025 | Balikatan 2023–2025 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Cases | 54 | 91 |

| Respiratory Illness Cases | 37 (69%) | 48 (53%) |

| Diarrheal Disease Cases | 17 (31%) | 43 (47%) |

| <30 years old | 37 (69%) | 60 (66%) |

| 30 to 39 years old | 11 (20%) | 22 (24%) |

| 40 to 49 years old | 5 (9%) | 2 (2%) |

| ≥50 years old | 1 (2%) | 6 (7%) |

| Male | 40 (93%) | 82 (90%) |

| Female | 5 (7%) | 9 (10%) |

| Pathogen | N | Geographic Origin of Nearest Reference Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Rhinoviruses | 1 | North America (1) |

| Enteroviruses | 0 | |

| Coronavirus 229E | 1 | North America (1) |

| Coronavirus HKU1 | 0 | North America (1) |

| Coronavirus NL63 | 0 | |

| Coronavirus OC43 | 4 | North America (4) |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 1 | North America (1) |

| Influenza A/pdm H1N1 | 1 | North America (1) |

| Parainfluenza 1 | 1 | Asia (1) |

| Parainfluenza 2 | 1 | Asia (1) |

| Parainfluenza 3 | 2 | North America (2) |

| Parainfluenza 4 | 0 | |

| No pathogen detected | 12 |

| Pathogen | N | AMP | AZM | CIP | NAL | ERY | SXT | CAZ | CRO | CTX | TE | IMP | MEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter coli | 2 | 50% | 100% | 100% | 50% | ||||||||

| Campylobacter jejuni | 3 | 33% | 100% | 100% | 0% | ||||||||

| EPEC | 7 | 71% | 14% | 0% | 0% | 29% | 0% | 14% | 14% | 71% | 14% | 0% | |

| ETEC | 3 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| EAEC | 6 | 67% | 17% | 17% | 17% | 17% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 83% | 0% | 0% | |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | 3 | 33% | 33% | 33% | 67% | 67% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Salmonella spp. | 10 | 60% | 0% | 10% | 20% | 20% | 10% | 10% | 10% | 60% | 0% | 0% | |

| Vibrio cholera (non O1/O139) | 1 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chaudhury, S.; Lertsethtakarn, P.; Chinnawirotpisan, P.; Ruamsap, N.; Kuntawunginn, W.; Thongpiam, C.; Pidtana, K.; Phontham, K.; Wongarunkochakorn, S.; Arsanok, M.; et al. Respiratory Illness and Diarrheal Disease Surveillance in U.S. Military Personnel Deployed to Southeast Asia for Military Exercises from 2023–2025. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10120353

Chaudhury S, Lertsethtakarn P, Chinnawirotpisan P, Ruamsap N, Kuntawunginn W, Thongpiam C, Pidtana K, Phontham K, Wongarunkochakorn S, Arsanok M, et al. Respiratory Illness and Diarrheal Disease Surveillance in U.S. Military Personnel Deployed to Southeast Asia for Military Exercises from 2023–2025. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(12):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10120353

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaudhury, Sidhartha, Paphavee Lertsethtakarn, Piyawan Chinnawirotpisan, Nattaya Ruamsap, Worachet Kuntawunginn, Chadin Thongpiam, Kingkan Pidtana, Kittijarankon Phontham, Saowaluk Wongarunkochakorn, Montri Arsanok, and et al. 2025. "Respiratory Illness and Diarrheal Disease Surveillance in U.S. Military Personnel Deployed to Southeast Asia for Military Exercises from 2023–2025" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 12: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10120353

APA StyleChaudhury, S., Lertsethtakarn, P., Chinnawirotpisan, P., Ruamsap, N., Kuntawunginn, W., Thongpiam, C., Pidtana, K., Phontham, K., Wongarunkochakorn, S., Arsanok, M., Poramathikul, K., Boonyarangka, P., Kietsiri, P., Oransathit, W., Gonwong, S., Wassanarungroj, P., Nobthai, P., Khemnu, N., Phonpakobsin, T., ... Boudreaux, D. M. (2025). Respiratory Illness and Diarrheal Disease Surveillance in U.S. Military Personnel Deployed to Southeast Asia for Military Exercises from 2023–2025. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(12), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10120353