Understanding Patient Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Study on Barriers and Facilitators to TB Care-Seeking in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

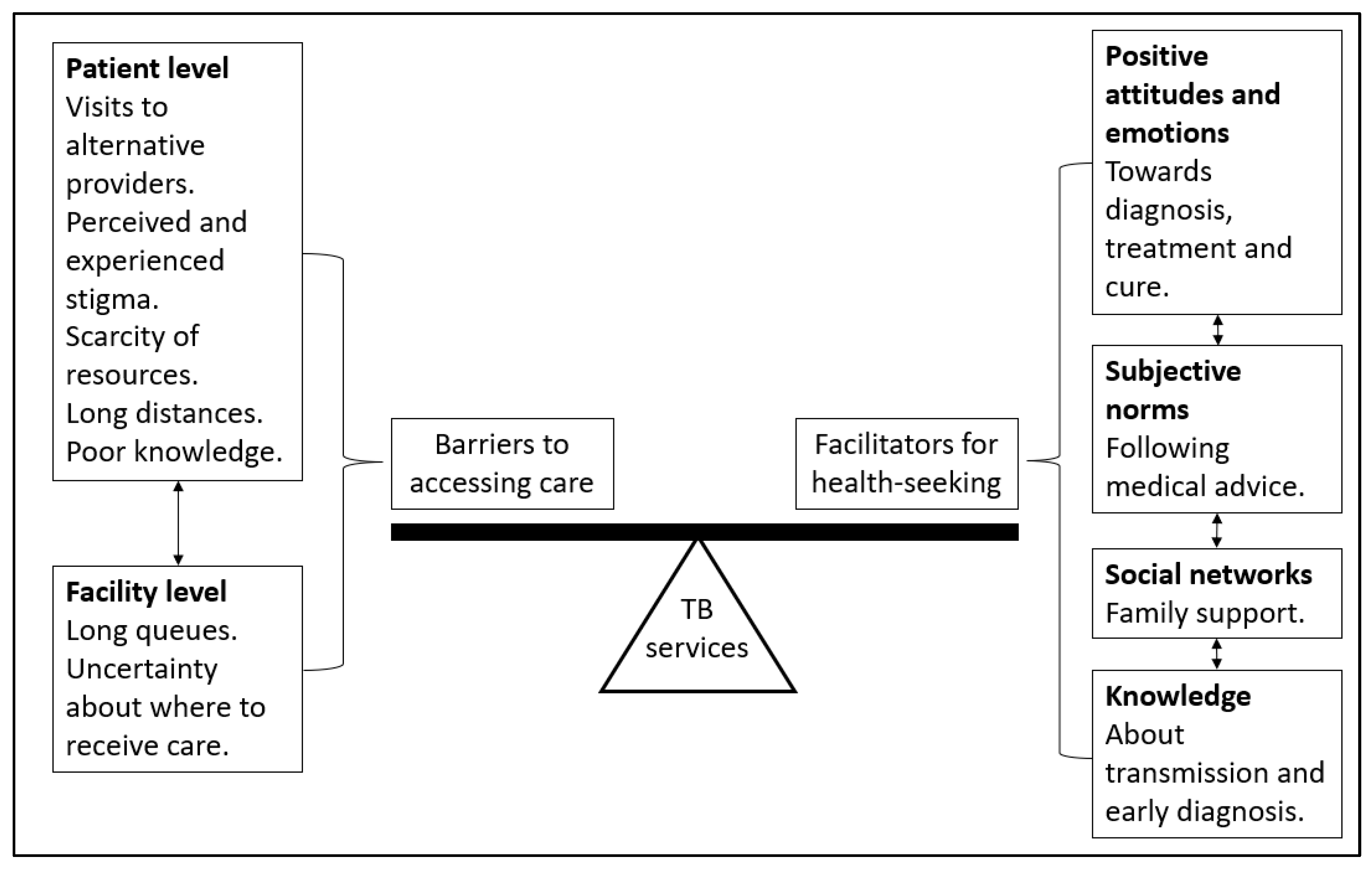

3.1. Theme 1: Barriers to Accessing TB Care

3.1.1. Pre-TB Diagnosis

“I did not start at the clinic because you know as black people we sometimes believe in witches.”(Male, 40 years, stigma score = 63)

“Then I went to see a guy who is a traditional healer, I went to see him and he gave me something for steaming and bathing.”(Male, 38 years, stigma score = 77)

“After coming from the doctor, I found out that I didn’t have the money to buy the things that he had prescribed.”(Male, 71 years, stigma score = 53)

“The first place I went to was {} the chemist, the chemist at the corner next to the garage. I went to the chemist, {} I do not like going to the clinic {} because I do not have money to go to the doctor, {so} I went to the chemist to tell them that it’s just flu.”(Male, 38 years, stigma score = 81)

“Ah I thought it was flu, something minor that will go away, I was busy taking grandpa, saying that it will go away.”(Female, 47 years, stigma score = 74)

“Sometimes {I} ask my brother to accompany me, we walk and take shortcuts.”(Female, 47 years, stigma score = 74)

“The distance is too long. Because your feet become painful when you’ve got TB, they have a stabbing sensation at the bottom.”(Male, 51 years, stigma score = 60)

“We struggle with transport this side.”(Female, 23 years, stigma score = 61)

“Is not too far but I wouldn’t prefer to go to my nearest clinic because there’s people that know me, so when they know that I am going there for this and that, they might look at me in another way, so I prefer going to the clinic that’s far from my community.”(Male, 23 years, stigma score = 37)

“They should not be afraid of me or avoid me because I have TB, like some not wanting to sit with me like we used to before, finding myself alone.”(Male, 37 years, stigma score = 46)

“I know people will say a lot about TB because mostly people they always say because you have TB it means you are HIV positive.”(Male, 23 years, stigma score = not available)

“My only experience was with the neighbour, who was like, oh he’ s got TB, he will pass it to us and I have {seen}{} other people, others even end up staying alone, no one wants to be close to them, when they walk on the street, they move and change directions.”(Male, 23 years, stigma score = 37)

3.1.2. Post-TB Diagnosis

“For me, the people I stay with, how can I protect them, that is what I want to understand.”(Female, 39 years, stigma score = 46)

“You can get it, when you eat from where they were eating, you can also get it.”(Male, 51 years, stigma score = 60)

“[Sighs], here the clinic, personally, to the tell you the truth I do not like coming to the clinic because you come, like my first time when I came. You do not know where you have to stand and it is packed {}, you see people who come every day, I think {they} are the ones that know where to go and sometimes the staff {are}{} not friendly. Like they will push you around. Asking you why you are seated here, things like that you see.”(Male, 38 years, stigma score = 81)

“If they can fast track the line {because}{} we are staying too long when we are here to collect or fetch our medication.”(Male, 32 years, stigma score = not available)

“It is getting food before you can get those pills because some of us are no longer working.”(Male, 51 years, stigma score = 60)

3.2. Theme 2: Facilitators for Health-Seeking

3.2.1. Pre-TB Diagnosis

“But when you start paying attention you then realize that it has been two {}{months} since I have been taking the medicine but nothing has changed.”(Male, 40 years, stigma score = 63)

“Yes, because I also got it like that, I got it from the person I was staying with and after some time it got into me.”(Male, 40 years, stigma score = 63)

“Me being in contact with a person who has TB and then like I saw all the symptoms in me as well, {}{yes} that’s why I decided to come to the clinic and get tested and see if I have, so, they have actually just told me that yes indeed I have TB.”(Male, 23 years, stigma score = not available)

“You know my reason for coming here was that I was bringing my grandchild here he was coughing and when I got here. I travelled to the clinic for a week and on the second week I was sent for X-ray, I was later contacted to be told that the results are out and they indicate that I have TB.”(Male, 70 years, stigma score = 74)

3.2.2. Post-TB Diagnosis

“What I can say is that they were reminding me not to skip taking my pills, they always prepared food for me, they did not let me stay alone, they were always with me.”(Male, 40 years, stigma score = 63)

“I also started coughing a lot like my uncle and he suggested that maybe I should also go to the clinic to get tested and then I went.”(Male, 38 years, stigma score = 81)

“So, he makes sure that there is food so that I can take pills, you see things like that.”(Female, 36 years, stigma score = 45)

“I did not have enough money to come here and I did not ask my son in-law, normally when I tell him, he brings me here.”(Female, 58 years, stigma score = 61)

“My mom was always there, whenever I need to talk she is there for me.”(Female, 23 years, stigma score = 61)

“I just need medication and to be reminded to eat my food, that is what I need.”(Male, 67 years, stigma score = 53)

“If you get it [TB] on time, if you find out early that you have TB, I mean its treatable, so, I just want people to you know, educate themselves about TB and once you see the symptoms you should rush to the clinic you know and get help before it’s too late.”(Male, 23 years, stigma score = not available)

“I just want to tell people that whenever you see anything or experience coughing and chest pains and everything, please rush to the clinic, if you go there, trust me they won’t even chase you, they won’t even shout at you, you will actually get the help that you need.”(Male, 23 years, stigma score = not available)

“Like the way I see it is that they are trying to stop it from infecting more people, so you have to start an early treatment so that you don’t affect a large number of people outside.”(Male, 25 years, stigma score = 48)

“TB is curable and if, if you take your medicine or your treatment right.”(Male, 32 years, stigma score = not available)

“So far it is good, I get the treatment, I get the support and there is follow up.”(Male, 48 years, stigma score = 46)

“I was so scared first, but I am glad that {} I know what is going on with my {} life now.”(Female, 55 years, stigma score = 44)

“You become scared {}, that it means that you can die, so I was feeling {} what if I die?”(Male, 38 years, stigma score = 81)

“I was thankful that at least I know and I will get help, I was thankful for that.”(Female, 47 years, stigma score = 74)

“Because they said that TB can be cured, {} it didn’t affect me bad.”(Male, 40 years, stigma score = 63)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2023 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Lienhardt, C.; Rowley, J.; Manneh, K.; Lahai, G.; Needham, D.; Milligan, P.; McAdam, K.P. Factors affecting time delay to treatment in a tuberculosis control programme in a sub-Saharan African country: The experience of The Gambia. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2001, 5, 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Sathar, F.; Charalambous, S.; Velen, K.; Fielding, K.; Rachow, A.; Ivanova, O.; Rassool, M.S.; Lalashowi, J.; Owolabi, O.; Nhassengo, P.; et al. Health-seeking behaviour and patient-related factors associated with the time to TB treatment initiation in four African countries: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Public Health 2024, 2, e001002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ereso, B.M.; Yimer, S.A.; Gradmann, C.; Sagbakken, M. Barriers for tuberculosis case finding in Southwest Ethiopia: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schacht, C.; Mutaquiha, C.; Faria, F.; Castro, G.; Manaca, N.; Manhiça, I.; Cowan, J. Barriers to access and adherence to tuberculosis services, as perceived by patients: A qualitative study in Mozambique. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemahagn, M.A.; Alene, G.D.; Yimer, S.A. A qualitative insight into barriers to tuberculosis case detection in east gojjam zone, Ethiopia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abimbola, S.; Ukwaja, K.N.; Onyedum, C.C.; Negin, J.; Jan, S.; Martiniuk, A.L.C. Transaction costs of access to health care: Implications of the care-seeking pathways of tuberculosis patients for health system governance in Nigeria. Glob. Public Health 2015, 10, 1060–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwakwa, L.; Sheu, M.L.; Chiang, C.Y.; Lin, S.L.; Chang, P.W. Patient and health system delays in the diagnosis and treatment of new and retreatment pulmonary tuberculosis cases in Malawi. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 132. Available online: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/14/132 (accessed on 29 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mbuthia, G.W.; Olungah, C.O.; Ondicho, T.G. Health-seeking pathway and factors leading to delays in tuberculosis diagnosis in West Pokot County, Kenya: A grounded theory study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhalu, G.; Weiss, M.G.; Hella, J.; Mhimbira, F.; Mahongo, E.; Schindler, C.; Reither, K.; Fenner, L.; Zemp, E.; Merten, S. Explaining patient delay in healthcare seeking and loss to diagnostic follow-up among patients with presumptive tuberculosis in Tanzania: A mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, D.M.; Foster, S.D.; Tomlinson, G.; Godfrey-Faussett, P. Socio-economic, gender and health services factors affecting diagnostic delay for tuberculosis patients in urban Zambia. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2001, 6, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordis-Worrall, J.; Hanson, K.; Mills, A. Confusion, Caring and Tuberculosis Diagnostic Delay in Cape Town, South Africa; International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease: Paris, France, 2010; Volume 14, Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/41027480_Confusion_caring_and_tuberculosis_diagnostic_delay_in_Cape_Town_South_Africa (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Makgopa, S.; Madiba, S. Tuberculosis Knowledge and Delayed Health Care Seeking Among New Diagnosed Tuberculosis Patients in Primary Health Facilities in an Urban District, South Africa. Health Serv. Insights 2021, 14, 11786329211054035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuge, T.G.; Bawore, S.G.; Solomon, D.W.; Hegana, T.Y. Patient delay in seeking tuberculosis diagnosis and associated factors in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datiko, D.G.; Jerene, D.; Suarez, P. Patient and health system delay among TB patients in Ethiopia: Nationwide mixed method cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, I.; Biewer, A.; Vanqa, N.; Makanda, G.; Tisile, P.; Hayward, S.E.; Wademan, D.T.; Anthony, M.G.; Mbuyamba, R.; Galloway, M.; et al. “This is an illness. No one is supposed to be treated badly”: Community-based stigma assessments in South Africa to inform tuberculosis stigma intervention design. BMC Glob. Public Health 2024, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaychoowong, K.; Watson, R.; Barrett, D.I. Perceptions of stigma among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Thailand, and the links to delays in accessing healthcare. J. Infect. Prev. 2023, 24, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaba, C.; Musoke, D.; Wafula, S.T.; Konde-Lule, J. Stigma among tuberculosis patients and associated factors in urban slum populations in Uganda. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ia, A.; Mo, O.; Alakija, W. Socio-Demographic Determinants of Stigma among Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2011, 11, S100–S104. [Google Scholar]

- National Department of Health; South African Medical Research Council; Human Sciences Research Council; National Institute for Communicable Diseases; World Health Organization. The First National TB Prevalence Survey (South Africa). 2018. Available online: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/elibrary/first-national-tb-prevalence-survey-south-africa-2018 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Moyo, S.; Ismail, F.; Mkhondo, N.; van der Walt, M.; Dlamini, S.S.; Mthiyane, T.; Naidoo, I.; Zuma, K.; Tadolini, M.; Law, I.; et al. Healthcare seeking patterns for TB symptoms: Findings from the first national TB prevalence survey of South Africa, 2017–2019. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rie, A.; Sengupta, S.; Pungrassami, P.; Balthip, Q.; Choonuan, S.; Kasetjaroen, Y.; Strauss, R.P.; Chongsuvivatwong, V. Measuring stigma associated with tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS in southern Thailand: Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of two new scales. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2008, 13, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyasulu, P.; Sikwese, S.; Chirwa, T.; Makanjee, C.; Mmanga, M.; Babalola, J.O.; Mpunga, J.; Banda, H.T.; Muula, A.S.; Munthali, A.C. Knowledge, beliefs, and perceptions of tuberculosis among community members in Ntcheu district, Malawi. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2018, 11, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edginton, M.E.; Sekatane, C.S.; Goldstein, S. Patients’ beliefs: Do they affect tuberculosis control? A study in a rural district of South Africa. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2002, 6, 1075–1082. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10935082 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Oga-Omenka, C.; Tseja-Akinrin, A.; Boffa, J.; Heitkamp, P.; Pai, M.; Zarowsky, C. Commentary: Lessons from the COVID-19 global health response to inform TB case finding. Healthcare 2021, 9, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.A.; Lewis, L.K.; Ferrar, K.; Marshall, S.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Vandelanotte, C. Are health behavior change interventions that use online social networks effective? A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, A.; Hunter, R.F.; Ajao, O.; Jurek, A.; McKeown, G.; Hong, J.; Barrett, E.; Ferguson, M.; McElwee, G.; McCarthy, M.; et al. Tweet for behavior change: Using social media for the dissemination of public health messages. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017, 3, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, T.; Booysen, F.; Mbonigaba, J. Socio-economic inequalities in the multiple dimensions of access to healthcare: The case of South Africa. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuady, A.; Anindhita, M.; Hanifah, M.; Putri, A.M.N.; Karnasih, A.; Agiananda, F.; Yani, F.F.; Haya, M.A.N.; Pakasi, T.A.; Wingfield, T. Codeveloping a community-based, peer-led psychosocial support intervention to reduce stigma and depression among people with tuberculosis and their households in Indonesia: A mixed-methods participatory action study. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2025, 35, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

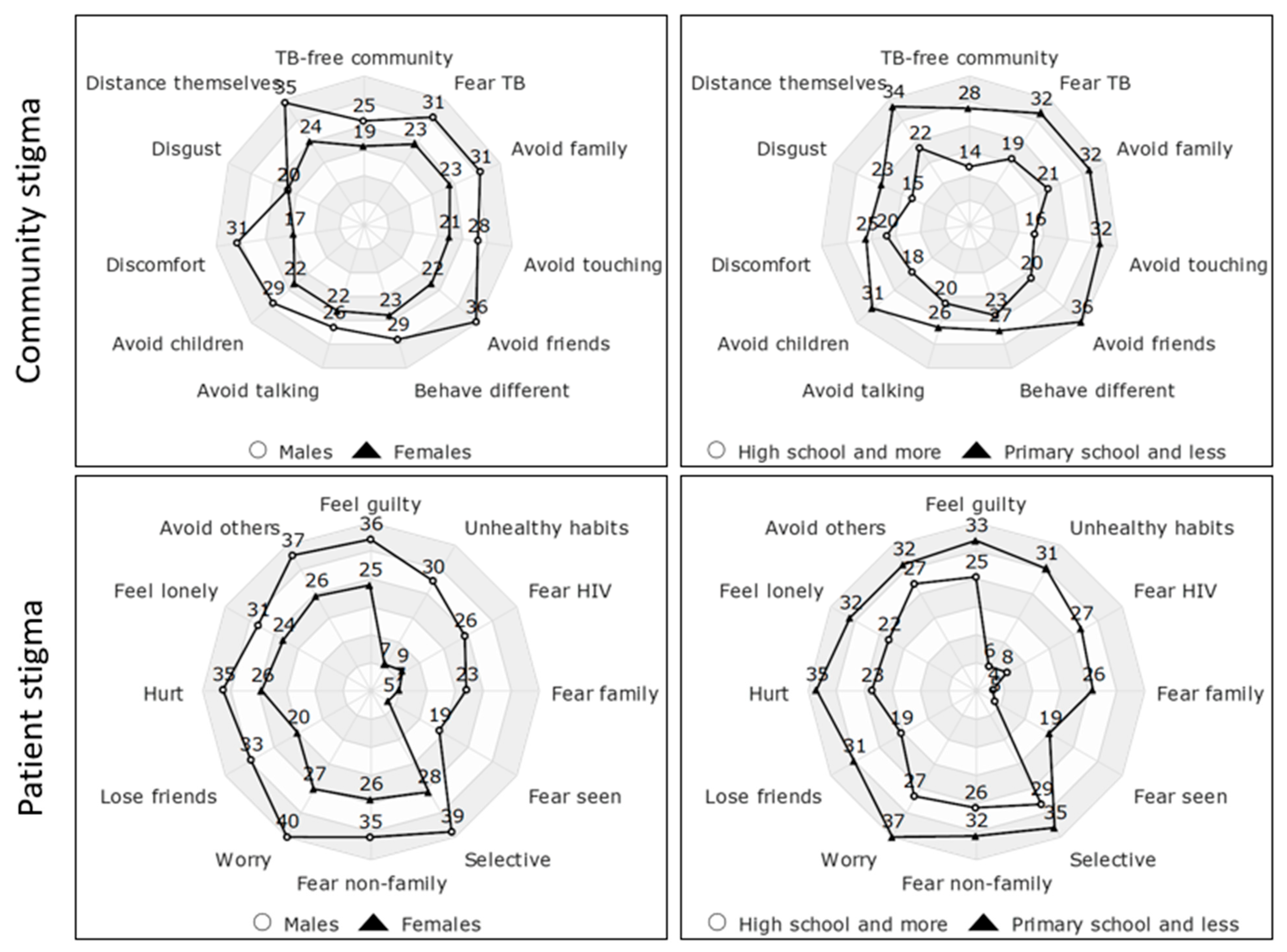

| Demographics | N (%) | Community Stigma Score | p Value | Patient Stigma Score | p Value | Total Stigma Score | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||||||

| Overall score | 21 | 25 (22–30) | 31 (21–36) | 53 (46–63) | ||||

| Sex | Male Female | 14 (61) 9 (39) | 27 (22–32) 24 (23–27) | 0.943 | 34 (24–37) 23 (19–34) | 0.126 | 57 (47–71) 46 (44–61) | 0.188 |

| Marital status | Cohabitation Married Single Widowed | 4 (17) 4 (17) 11 (48) 1 (4) | 34 (26–37) 22 (21–30) 25 (22–30) 38 (38–38) | 0.136 | 34 (17–43) 31 (25–33) 34 (21–37) 36 (36–36) | 0.879 | 60 (54–77) 53 (46–63) 53 (45–67) 74 (74–74) | 0.495 |

| Education | No formal schooling Primary school High school Vocational training | 5 (22) 6 (26) 7 (30) 4 (17) | 34 (30–34) 29 (22–35) 23 (20–26) 24 (23–25) | 0.160 | 33 (17–43) 36 (34–37) 23 (21–25) 28 (19–36) | 0.164 | 63 (54–77) 64 (53–74) 46 (44–48) 52 (42–61) | 0.063 |

| Employment | Yes No | 8 (35) 15 (65) | 27 (22–30) 25 (22–34) | 0.876 | 28 (18–37) 31 (21–36) | 0.755 | 55 (39–67) 53 (46–61) | 0.815 |

| First provider visited | Pharmacy Public clinic Public hospital Traditional healer | 3 (15) 12 (60) 2 (10) 3 (15) | 25 (19–27) 25 (22–34) 27 (17–37) 30 (30–34) | 0.531 | 34 (18–36) 28 (21–36) 27 (17–36) 37 (33–43) | 0.499 | 61 (37–61) 51 (44–74) 54 (53–54) 67 (63–77) | 0.331 |

| Pre-TB Diagnosis | Post-TB Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Barriers | |

| Lack of resources | Long waiting times |

| Lack of TB suspicion | Staff attitudes |

| Long distances to the clinic | Stigma |

| Stigma | |

| Facilitators | |

| Symptoms not improving | Being cured with treatment |

| Lack of resources | Staff attitudes |

| Suspicion of TB | Family support |

| Family support | Fear of dying |

| Fear of dying | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sathar, F.; du Toit, C.; Chihota, V.; Charalambous, S.; Evans, D.; Chetty-Makkan, C. Understanding Patient Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Study on Barriers and Facilitators to TB Care-Seeking in South Africa. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10100283

Sathar F, du Toit C, Chihota V, Charalambous S, Evans D, Chetty-Makkan C. Understanding Patient Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Study on Barriers and Facilitators to TB Care-Seeking in South Africa. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(10):283. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10100283

Chicago/Turabian StyleSathar, Farzana, Claire du Toit, Violet Chihota, Salome Charalambous, Denise Evans, and Candice Chetty-Makkan. 2025. "Understanding Patient Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Study on Barriers and Facilitators to TB Care-Seeking in South Africa" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 10: 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10100283

APA StyleSathar, F., du Toit, C., Chihota, V., Charalambous, S., Evans, D., & Chetty-Makkan, C. (2025). Understanding Patient Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Study on Barriers and Facilitators to TB Care-Seeking in South Africa. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(10), 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10100283