Abstract

Multimodal interaction refers to situations where users are provided with multiple modes for interacting with systems. Researchers are working on multimodality solutions in several domains. The focus of this paper is within the domain of navigation systems for supporting users with visual impairments. Although several literature reviews have covered this domain, none have gone through the research synthesis of multimodal navigation systems. This paper provides a review and analysis of multimodal navigation solutions aimed at people with visual impairments. This review also puts forward recommendations for effective multimodal navigation systems. Moreover, this review also presents the challenges faced during the design, implementation and use of multimodal navigation systems. We call for more research to better understand the users’ evolving modality preferences during navigation.

1. Introduction

Navigation is an essential activity in human life. Montello [1] describes navigation as “coordinated and goal-directed movement through the environment by a living entity or intelligent machines.” Navigation requires both planning and execution of movements. Several works [2,3,4,5], divide navigation into two components: orientation and mobility. Orientation refers to the process of keeping track of position and wayfinding, while mobility refers to obstacle detection and avoidance. Hence, effective navigation involves both mobility and orientation skills.

Several studies have documented that people with visual impairments often find navigation challenging [6,7,8]. These challenges may include issues with cognitive mapping, lack of access, spatial inference and updating [3,5,6], to mention a few. More complex spatial behaviors, such as integrating local information into a global understanding of layout configuration (e.g., a cognitive map); determining detours or shortcuts; and re-orienting if lost, can be performed only by a person with good mobility and orientation skills. These skills are critical for accurate wayfinding, which involves planning and determining routes through an environment. People with visual impairments may lack those skills and consequently may struggle to navigate successfully [5]. Obstacles can be avoided effectively using conventional navigation aids, such as a white cane or a guide dog [9]. However, these aids do not provide vital information about the surrounding environment. Giudice [6] describes that it is difficult to gain access to environmental information without vision, yet it is essential for effective decision making, environmental learning, spatial updating and cognitive map development. Moreover, visual experiences play a critical role in accurate spatial learning, for the development of spatial representations and for guiding spatial behaviors [3]. Giudice [6] claims that spatial knowledge acquisition is slower and less accurate without visual experience.

The studies conducted by Al-Ammar et al. [10] show that to improve the navigation accessibility of users with visual impairment, one needs to enable navigation as an independent and safe activity. Conventional navigation aids such as white canes and guide dogs have a long history [11,12]. Studies have also shown that there are limitations associated with such conventional tools [11]. To improve upon conventional navigation aids, several navigation systems have been proposed that use different technologies [13,14,15]. They are designed to work indoors, outdoors or both [15] and rely on certain technologies [2,16]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines such tools collectively as “assistive technology” [17]. WHO further points out that assistive technology products maintain or improve an individual’s functioning and independence by nurturing their well-being. Hersh and Johnson [11] elaborated that assistive navigation tools for users with visual impairments have the potential to describe the environment such that obstacles can be avoided. Different devices and systems have been proposed for navigation support to users with visual impairments. These devices and techniques can be divided into three categories [9]: electronic travel aids (ETAs), electronic orientation aids (EOAs) and position locator devices (PLDs) [18]. ETAs are general devices to help people with visual impairments avoid obstacles. ETAs may have sensing inputs such as depth cameras, general cameras, radio frequency identification (RFID), ultrasonic sensors and infrared sensors. EOAs help visually impaired people navigate in unknown environments. These systems provide guiding directions and obstacle warnings. PLDs help determine the precise position of a device, and use technologies such as the Global Positioning System (GPS) and geographic information systems (GISs). Lin et al. [18] gives a detailed explanation of these categories. In this paper, the term “navigation system” is used to denote any tool, aid or device that provide navigation support to users with visual impairments. In addition, we use the term “users” or “target users” to denote the term “users with visual impairments”.

Researchers have been exploring the navigation support applications of emerging technologies for several decades [19]. Advancements in computer vision, wearable technology, multisensory research and medicine have led to the design and development of various assistive technology solutions, particularly in the domain of navigation systems for supporting users with visual impairments [14,20]. Ton et al. [21] observed that the research had explored a wide range of technology-mediated sensory-substitution to compensate for vision loss. The developments in artificial intelligence (AI)—in object detection using machine learning algorithms, location identification using sensors, etc.—can be exploited to understand the environment during navigation. The developments in smartphone technologies have also opened up new possibilities in navigation system design [22,23,24]. One key challenge is how to communicate the information in a simple and understandable form to the user, especially as other senses (touch, hearing, smell and taste) have lower bandwidths than vision [13]. Therefore, effective communication of relevant information to the users is a major requirement for such navigation systems.

Bernsen and Dybkjr [25] defines the term modality in the human–computer interaction (HCI) domain as a way of representing or communicating information in some medium. The term “multimodality” refers to the use of different modalities together to perform a task or a function [26,27]. Modalities are typically visual, aural or haptic [28]. Navigation systems that use different modes to communicate with the user are called multimodal navigation systems [29]. Several multimodal systems were proposed to assist users for navigation [30,31,32]. Many prototypes have been reported without much practical evaluation involving target users [30]. It is therefore uncertain whether these proposals offer any actual benefits to users. A few studies have also been published with convincing validation involving the users [33,34].

Several surveys have addressed navigation systems designed for users with visual impairments [13,14,15,35]. Some focused on the types of devices or technology, while others on the environments of use. To the best of our knowledge, no systematic surveys have addressed multimodal navigation systems. This paper, therefore, provides an overview of the major advances in multimodal navigation systems for supporting users with visual impairments.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the general theory of multimodality. Section 3 gives a brief overview of the application of multimodality in the navigation system and also describes the methodology we used for this review. Section 4 discusses the multimodal navigation systems and their affiliated studies. Section 5 summarizes the challenges and presents a set of recommendations for the design of a multimodal navigation system for people with visual impairments. The paper concludes in Section 6.

2. Multimodality in Human–Computer Interaction

In the context of HCI, a modality can be considered as a single sensory channel of input and output between a computer and a human [28,36]. A unimodal system uses one modality, whereas a multimodal system relies on several modalities [36]. Studies have shown that multimodal systems can provide more flexibility and reliability compared to unimodal systems [37,38]. Oviatt et al. [39] elaborates on the possible advantages of a multimodal interaction system, such as freedom to use a combination of modalities or to switch to a more-suited modality. Designers and developers working with HCI have also tried to utilize different modalities to provide complementary solutions to a task that may be redundant in function but convey information more robustly to the user [40,41]. Based on the perception of information, modalities can be generally defined in two forms: human–computer (input) and computer–human (output) [27]. During the interaction, the available input modalities are utilized by the user to communicate with the system, and the system uses several output modalities to communicate back to the user [42].

Computers utilize multiple modalities to communicate and send information to users [43]. Vision is the most frequently used modality, followed by audio and haptic. Haptic communication occurs through vibrations or other tactile sensations. Examples of touch-based (haptic) modality channels include smartphone vibrations. The other modalities such as smell, taste and heat are less used in interactive systems [44]. Audio offers the benefits of rich interaction experiences depending on the context of use and helps provide more robust systems when used in combination with other modalities [45]. Such redundancies are used when a user wants to communicate with a system via voice while driving a car without taking the hands off the steering wheel.

Epstein [46] and Grifoni et al. [47] have shown that with the increasing use of smartphones and other mobile devices, users are becoming more comfortable in experimenting with different new modalities. After the introduction of voice assistants such as Siri, Alexa, Cortana and Google Home, some users began to use voice assistants as an alternative way to communicate with computers and other digital devices [48,49]. This epitomizes how certain modalities with contrasting strengths are useful in various situations [50]. Some other modalities such as computer vision can be utilized to capture three-dimensional gesticulations using depth cameras, such as Microsoft Kinect [44].

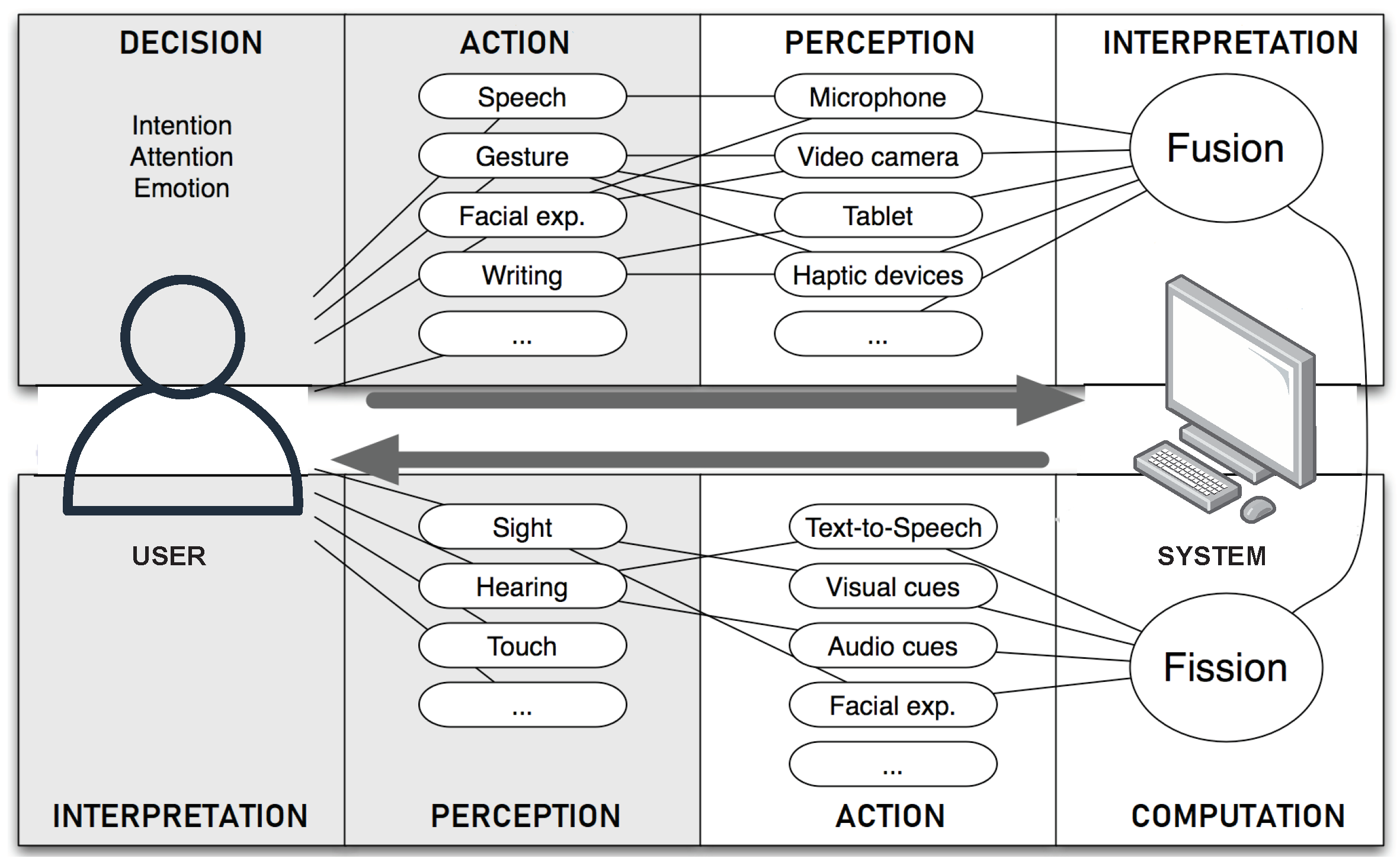

Multimodal systems have the potential to increase accessibility to users by relying on different modalities. Due to the benefits of using multimodal inputs and outputs, multimodal fusion is also used in various applications to support user needs [51]. The process of integrating information from multiple input modalities and combining them into a specific format for further processing is termed multimodal fusion [52,53]. To allow their interpretation, a multimodal system must recognize different input modalities and combine them according to temporal and contextual constraints [47,54,55]. An example of a multimodal human–computer interaction system is illustrated in Figure 1. This two-level flow of modalities (action and perception) explains how a user and a system interact with each other and also the different steps involving in the process [56].

Figure 1.

Multimodal human–computer interaction (adapted from [56]).

4. Discussion

Behavioral and cognitive neuroscience studies conducted by Ho et al. [90], Stanney et al. [91] and Calvert et al. [92] show that systems with multiple modalities can maximize user information processing. Moreover, systems designed with multimodal preferences can provide various combinations of signals from different sensory modalities and subsequently have beneficial effects on user performance with a particular system. Lee and Spence [93] argued that the presentation of multimodal feedback outputs to users was found to have enhanced performance and more pronounced benefits over unimodal systems. However, other studies [94,95,96] claim that multimodal feedback modes can confuse users. Confusion may occur when the user has several multimodal options for one function with a similar purpose but can enter into a dilemma on what to choose and which one is better. In terms of design considerations of a multimodal navigation system, it is important to consider how effectively and easily each of the multimodal feedback methods can be utilized by the users.

Common modalities used in almost all multimodal navigation systems are aural and tactile (see Table 1). Some systems enhance the audio with spatial or 3D audio. Many systems tested their prototypes with the target users, while some reported tests with blindfolded users. Some authors did not document any user evaluation of their systems.

The multimodal interfaces discussed in this review mostly utilized mobile systems such as tablets and smartphones (see Table 2). Different modalities such as aural (in the form of messages and non-speech alerts) and vibration cues were used in the systems for interaction. The multimodal maps mainly used the aural and tactile modalities (see Table 3). In cases in which systems have not been evaluated with users, it is impossible to conclude whether the intentions of the systems were met.

The different hardware components in the virtual-navigation laboratory environment can simulate different modalities in the real-time environments (see Table 4). The common modalities—such as audio, and haptic and its variants, such as vibration and force feedback—could be simulated in a virtual environment setup. These virtual training platforms claimed to help the users to experience the multimodal navigation systems before proceeding to the navigation in real environments.

It is interesting to note that almost all multimodal systems reviewed here employed the aural modality. Some user-interaction studies validate this perspective by pointing out that speech cues can be useful in providing mobility feedback for users [97,98]. This may be because audio modality can be a suitable choice when the users want to hear information about the environment during navigation. Moreover, empirical results show that users are uncomfortable when using audio feedback in public environments [99]. In noisy environments such as public places, it can be challenging to hear audio feedback. Additionally, users might have a social stigma when they think that auditory feedback is audible to the public as well. There are also privacy and security concerns in using audio feedback in public environments.

The advantage of haptic feedback is that the users can use it anywhere, anytime, without interrupting others. At the same time, vibrations are often more similar to each other, and not easy to distinguish compared to auditory feedback, which might create confusion among users [99].

6. Conclusions

Multimodal technology can be considered as a promising option that can be utilized in the design of effective and accessible navigation systems for users with visual impairments. Multimodal navigation solutions proposed for people with visual impairments were reviewed. The primary modalities that are utilized in almost every multimodal navigation system discussed in this review are aural and tactile. Even though many multimodal navigation solutions have been proposed, there is little evidence of what degree the target users continued to use these technologies in practice. Studies concerning the extent to which multimodal systems are helpful for people with visual impairments in real-life navigation contexts are an important avenue to consider. Challenges are associated with designing, implementing and using multimodal navigation systems. Exploring the effectiveness of recent advancements in artificial intelligence and related technologies to help with tackling the different challenges in multimodality is an important area of future research. Moreover, we argue that more studies are needed to better understand the evolving preferences in modalities among users with visual impairments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K.; methodology, B.K.; investigation, B.K.; writing–original draft preparation, B.K.; writing–review and editing, R.S. and F.E.S.; visualization, B.K.; supervision, R.S. and F.E.S.; project administration, R.S.; funding acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments throughout the manuscript revision process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Montello, D.R. Navigation. In The Cambridge Handbook of Visuospatial Thinking; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 257–294. [Google Scholar]

- Giudice, N.A.; Legge, G.E. Blind navigation and the role of technology. In The Engineering Handbook of Smart Technology for Aging, Disability, Additionally, Independence; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 8, pp. 479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Schinazi, V.R.; Thrash, T.; Chebat, D.R. Spatial navigation by congenitally blind individuals. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 2016, 7, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thinus-Blanc, C.; Gaunet, F. Representation of space in blind persons: Vision as a spatial sense? Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, R.G.; Hill, E. Establishing and maintaining orientation for mobility. In Foundations of Orientation and Mobility; American Foundation for the Blind: Arlington County, VA, USA, 1997; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Giudice, N.A. Navigating without vision: Principles of blind spatial cognition. In Handbook of Behavioral and Cognitive Geography; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Riazi, A.; Riazi, F.; Yoosfi, R.; Bahmeei, F. Outdoor difficulties experienced by a group of visually impaired Iranian people. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2016, 28, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manduchi, R.; Kurniawan, S. Mobility-related accidents experienced by people with visual impairment. AER J. Res. Pract. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2011, 4, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, A.D.P.; Medola, F.O.; Cinelli, M.J.; Ramirez, A.R.G.; Sandnes, F.E. Are electronic white canes better than traditional canes? A comparative study with blind and blindfolded participants. In Universal Access in the Information Society; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ammar, M.A.; Al-Khalifa, H.S.; Al-Salman, A.S. A proposed indoor navigation system for blind individuals. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Information Integration and Web-based Applications and Services, Ho Chi Minh City, Vitenam, 5–7 December 2011; pp. 527–530. [Google Scholar]

- Hersh, M.; Johnson, M.A. Assistive Technology for Visually Impaired and Blind People; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, O. Assistive Technology: Principles and Applications For Communication Disorders and Special Education; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chanana, P.; Paul, R.; Balakrishnan, M.; Rao, P. Assistive technology solutions for aiding travel of pedestrians with visual impairment. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, A.; Hazarika, S.M. An insight into assistive technology for the visually impaired and blind people: State-of-the-art and future trends. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2017, 11, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, S.; Araujo, A. Navigation Systems for the Blind and Visually Impaired: Past Work, Challenges, and Open Problems. Sensors 2019, 19, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersh, M. The design and evaluation of assistive technology products and devices Part 1: Design. In International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation; Blouin, M., Stone, J., Eds.; Center for International Rehabilitation Research Information and Exchange (CIRRIE), University at Buffalo: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Available online: http://sphhp.buffalo.edu/rehabilitation-science/research-and-facilities/funded-research-archive/center-for-international-rehab-research-info-exchange.html (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Assistive Technology. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/assistive-technology (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Lin, B.S.; Lee, C.C.; Chiang, P.Y. Simple smartphone-based guiding system for visually impaired people. Sensors 2017, 17, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Khusro, S.; Ullah, I. Technology-assisted white cane: Evaluation and future directions. PeerJ 2018, 6, e6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manduchi, R.; Coughlan, J. (Computer) vision without sight. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton, C.; Omar, A.; Szedenko, V.; Tran, V.H.; Aftab, A.; Perla, F.; Bernstein, M.J.; Yang, Y. LIDAR Assist spatial sensing for the visually impaired and performance analysis. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 1727–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croce, D.; Giarré, L.; Pascucci, F.; Tinnirello, I.; Galioto, G.E.; Garlisi, D.; Valvo, A.L. An indoor and outdoor navigation system for visually impaired people. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 170406–170418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galioto, G.; Tinnirello, I.; Croce, D.; Inderst, F.; Pascucci, F.; Giarré, L. Sensor fusion localization and navigation for visually impaired people. In Proceedings of the 2018 European Control Conference (ECC), Limassol, Cyprus, 12–15 June 2018; pp. 3191–3196. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, B.; Shrestha, R.; Sandnes, F.E. Smartphone Navigation Support for Blind and Visually Impaired People-A Comprehensive Analysis of Potentials and Opportunities. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 568–583. [Google Scholar]

- Bernsen, N.O.; Dybkjær, L. Modalities and Devices; Springer: London, UK, 2010; pp. 67–111. [Google Scholar]

- What Is Multimodality. 2013. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/new-telerehabilitation-services-elderly/19644 (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Mittal, S.; Mittal, A. Versatile question answering systems: Seeing in synthesis. Int. J. Intell. Inf. Database Syst. 2011, 5, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaimes, A.; Sebe, N. Multimodal human–computer interaction: A survey. Comput. Vis. Image Understand. 2007, 108, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguet, M.L. Designing and Prototyping Multimodal Commands; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 3, pp. 717–720. [Google Scholar]

- Bourbakis, N.; Keefer, R.; Dakopoulos, D.; Esposito, A. A multimodal interaction scheme between a blind user and the tyflos assistive prototype. In Proceedings of the 2008 20th IEEE International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence, Dayton, OH, USA, 3–5 November 2008; Volume 2, pp. 487–494. [Google Scholar]

- Basori, A.H. HapAR: Handy Intelligent Multimodal Haptic and Audio-Based Mobile AR Navigation for the Visually Impaired. In Technological Trends in Improved Mobility of the Visually Impaired; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 319–334. [Google Scholar]

- Fusiello, A.; Panuccio, A.; Murino, V.; Fontana, F.; Rocchesso, D. A multimodal electronic travel aid device. In Proceedings of the Fourth IEEE International Conference on Multimodal Interfaces, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 16 October 2002; pp. 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, V.; Budhai, M.; Olmschenk, G.; Seiple, W.H.; Zhu, Z. ASSIST: Personalized indoor navigation via multimodal sensors and high-level semantic information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 128–143. [Google Scholar]

- Caraiman, S.; Morar, A.; Owczarek, M.; Burlacu, A.; Rzeszotarski, D.; Botezatu, N.; Herghelegiu, P.; Moldoveanu, F.; Strumillo, P.; Moldoveanu, A. Computer vision for the visually impaired: The sound of vision system. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1480–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, B.; Shrestha, R.; Sandnes, F.E. Tools and Technologies for Blind and Visually Impaired Navigation Support: A Review. IETE Tech. Rev. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karray, F.; Alemzadeh, M.; Saleh, J.A.; Arab, M.N. Human-computer interaction: Overview on state of the art. Int. J. Smart Sens. Intell. Syst. 2008, 1, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, S.; Lunsford, R.; Coulston, R. Individual differences in multimodal integration patterns: What are they and why do they exist? In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Portland, OR, USA, 2–7 April 2005; pp. 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bohus, D.; Horvitz, E. Facilitating multiparty dialog with gaze, gesture, and speech. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Multimodal Interfaces and the Workshop on Machine Learning for Multimodal Interaction, Beijing, China, 2–12 November 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Oviatt, S.; Cohen, P.; Wu, L.; Duncan, L.; Suhm, B.; Bers, J.; Holzman, T.; Winograd, T.; Landay, J.; Larson, J.; et al. Designing the user interface for multimodal speech and pen-based gesture applications: State-of-the-art systems and future research directions. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2000, 15, 263–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.S.; Jo, K.H.; Figueroa-García, J.C. Intelligent Computing Theories and Application. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference, ICIC 2017, Liverpool, UK, 7–10 August 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 10362. [Google Scholar]

- Palanque, P.; Graham, T.C.N. Interactive Systems. Design, Specification, and Verification. In Proceedings of the 7th International Workshop, DSV-IS 2000, Limerick, Ireland, 5–6 June 2000; Revised Papers, Number 1946. Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bernsen, N.O. Multimodality theory. In Multimodal User Interfaces; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jacko, J.A. Human Computer Interaction Handbook: Fundamentals, Evolving Technologies, and Emerging Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kurosu, M. Human-Computer Interaction: Interaction Modalities and Techniques. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference, HCI International 2013, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–26 July 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 8007. [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge, W.S. Berkshire Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction; Berkshire Publishing Group LLC: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Z. Siri Said to Be Driving Force behind Huge iPhone 4S Sales. 2011. Available online: https://bgr.com/2011/11/02/siri-said-to-be-driving-force-behind-huge-iphone-4s-sales/ (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Grifoni, P.; Ferri, F.; Caschera, M.C.; D’Ulizia, A.; Mazzei, M. MIS: Multimodal Interaction Services in a cloud perspective. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1704.00972. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy, M.B. Alexa, Siri, Cortana, and more: An introduction to voice assistants. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2018, 37, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepuska, V.; Bohouta, G. Next-generation of virtual personal assistants (microsoft cortana, apple siri, amazon alexa and google home). In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 8th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 8–10 January 2018; pp. 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kurkovsky, S. Multimodality in Mobile Computing and Mobile Devices: Methods for Adaptable Usability; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Djaid, N.T.; Saadia, N.; Ramdane-Cherif, A. Multimodal Fusion Engine for an Intelligent Assistance Robot Using Ontology. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 52, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, A.; Mehta, M.; Bernsen, N.O.; Martin, J.; Abrilian, S. Multimodal input fusion in human-computer interaction. NATO Sci. Ser. Sub Ser. III Comput. Syst. Sci. 2005, 198, 223. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ulizia, A. Exploring multimodal input fusion strategies. In Multimodal Human Computer Interaction and Pervasive Services; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 34–57. [Google Scholar]

- Caschera, M.C.; Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P. Multimodal interaction systems: Information and time features. Int. J. Web Grid Serv. 2007, 3, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, P. Multimodal Human Computer Interaction and Pervasive Services; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, B.; Lalanne, D.; Oviatt, S. Multimodal interfaces: A survey of principles, models and frameworks. In Human Machine Interaction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vainio, T. Exploring cues and rhythm for designing multimodal tools to support mobile users in wayfinding. In CHI’09 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 3715–3720. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, A.M.; Truillet, P.; Oriola, B.; Picard, D.; Jouffrais, C. Interactivity improves usability of geographic maps for visually impaired people. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2015, 30, 156–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternó, F. Interactive Systems: Design, Specification, and Verification. In Proceedings of the 1st Eurographics Workshop, Bocca Di Magra, Italy, 8–10 June 1994; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, A.; Jacko, J.A. Human-Computer Interaction: Designing for Diverse Users and Domains; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Bie, J.; Ben Allouch, S.; Jaschinski, C. Communicating Multimodal Wayfinding Messages For Visually Impaired People Via Wearables. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Taipei Taiwan, 1–4 October 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M. Benefits of Bone Conduction and Bone Conduction Headphones. 2019. Available online: https://www.soundguys.com/bone-conduction-headphones-20580/ (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Gallo, S.; Chapuis, D.; Santos-Carreras, L.; Kim, Y.; Retornaz, P.; Bleuler, H.; Gassert, R. Augmented white cane with multimodal haptic feedback. In Proceedings of the 2010 3rd IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics, Tokyo, Japan, 26–29 September 2010; pp. 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Weber, G.; Simros, M.; Conradie, P.; Saldien, J.; Ravyse, I.; van Erp, J.; Mioch, T. Range-IT: Detection and multimodal presentation of indoor objects for visually impaired people. In Proceedings of the MobileHCI ’17: 19th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Vienna, Austria, 4–7 September 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.M.F.; Riener, A.; Bose, R.; Jeon, M. “Listen2dRoom”: Helping Visually Impaired People Navigate Indoor Environments Using an Ultrasonic Sensor-Based Orientation Aid; Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmetovic, D.; Gleason, C.; Ruan, C.; Kitani, K.; Takagi, H.; Asakawa, C. NavCog: A navigational cognitive assistant for the blind. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Florence, Italy, 6–9 September 2016; pp. 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Chen, J.; Franklin, T.; Zhang, L.; Ruci, A.; Tang, H.; Zhu, Z. Multimodal Information Integration for Indoor Navigation Using a Smartphone. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 21st International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IRI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–13 August 2020; pp. 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Loomis, J.M.; Golledge, R.G.; Klatzky, R.L. Navigation system for the blind: Auditory display modes and guidance. Presence 1998, 7, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.M.; Marston, J.R.; Golledge, R.G.; Klatzky, R.L. Personal guidance system for people with visual impairment: A comparison of spatial displays for route guidance. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2005, 99, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.C.; Katzschmann, R.K.; Teng, S.; Araki, B.; Giarré, L.; Rus, D. Enabling independent navigation for visually impaired people through a wearable vision-based feedback system. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 6533–6540. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, C.; Payandeh, S. Multimodal Sensing Interface for Haptic Interaction. J. Sens. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, J.C.; Cielniak, G.; Bellotto, N. A Portable Navigation System with an Adaptive Multimodal Interface for the Blind; 2017 AAAI Spring Symposium Series; Stanford, CA, USA, 27–29 March 2017; AAAI: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bellotto, N. A multimodal smartphone interface for active perception by visually impaired. In IEEE SMC International Workshop on Human-Machine Systems, Cyborgs and Enhancing Devices (HUMASCEND); IEEE: Manchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Turunen, M.; Hakulinen, J.; Kainulainen, A.; Melto, A.; Hurtig, T. Design of a rich multimodal interface for mobile spoken route guidance. In Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, Antwerp, Belgium, 27–31 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ducasse, J.; Brock, A.M.; Jouffrais, C. Accessible interactive maps for visually impaired users. In Mobility of Visually Impaired People; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 537–584. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, A.; Truillet, P.; Oriola, B.; Picard, D.; Jouffrais, C. Design and user satisfaction of interactive maps for visually impaired people. In International Conference on Computers for Handicapped Persons; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 544–551. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, B.; Hedgpeth, T.; Haven, T. Instant tactile-audio map: Enabling access to digital maps for people with visual impairment. In Proceedings of the 11th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Pittsbuirgh, PA, USA, 25–28 October 2009; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Miele, J.A.; Landau, S.; Gilden, D. Talking TMAP: Automated generation of audio-tactile maps using Smith-Kettlewell’s TMAP software. Br. J. Vis. Impair. 2006, 24, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, N.A.; Guenther, B.A.; Jensen, N.A.; Haase, K.N. Cognitive mapping without vision: Comparing wayfinding performance after learning from digital touchscreen-based multimodal maps vs. embossed tactile overlays. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppinga, B.; Magnusson, C.; Pielot, M.; Rassmus-Gröhn, K. TouchOver map: Audio-tactile exploration of interactive maps. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Stockholm, Sweden, 30 August–2 September 2011; pp. 545–550. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Weber, G. Exploration of location-aware you-are-here maps on a pin-matrix display. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2015, 46, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahram, S. Multimodal eyes-free exploration of maps: TIKISI for maps. ACM SIGACCESS Access. Comput. 2013, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatani, K.; Banovic, N.; Truong, K. SpaceSense: Representing geographical information to visually impaired people using spatial tactile feedback. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012; pp. 415–424. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, A.; Miesenberger, K.; Zeng, L.; Weber, G. Virtual navigation environment for blind and low vision people. In International Conference on Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lécuyer, A.; Mobuchon, P.; Mégard, C.; Perret, J.; Andriot, C.; Colinot, J.P. HOMERE: A multimodal system for visually impaired people to explore virtual environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 22–26 March 2003; pp. 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Rivière, M.A.; Gay, S.; Romeo, K.; Pissaloux, E.; Bujacz, M.; Skulimowski, P.; Strumillo, P. NAV-VIR: An audio-tactile virtual environment to assist visually impaired people. In Proceedings of the 2019 9th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–23 March 2019; pp. 1038–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, W.L.; Seidel, E.L.; Zhu, Z. Designing a virtual environment to evaluate multimodal sensors for assisting the visually impaired. In International Conference on Computers for Handicapped Persons; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 573–580. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Bennett, C.L.; Benko, H.; Cutrell, E.; Holz, C.; Morris, M.R.; Sinclair, M. Enabling people with visual impairments to navigate virtual reality with a haptic and auditory cane simulation. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lahav, O.; Schloerb, D.; Kumar, S.; Srinivasan, M. A virtual environment for people who are blind–a usability study. J. Assist. Technol. 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.; Reed, N.; Spence, C. Multisensory in-car warning signals for collision avoidance. Hum. Factors 2007, 49, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanney, K.; Samman, S.; Reeves, L.; Hale, K.; Buff, W.; Bowers, C.; Goldiez, B.; Nicholson, D.; Lackey, S. A paradigm shift in interactive computing: Deriving multimodal design principles from behavioral and neurological foundations. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2004, 17, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, G.; Spence, C.; Stein, B.E. The Handbook of Multisensory Processes; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Spence, C. Assessing the benefits of multimodal feedback on dual-task performance under demanding conditions. In Proceedings of the 22nd British HCI Group Annual Conference on People and Computers: Culture, Creativity, Interaction (HCI), Liverpool, UK, 1–5 September 2008; pp. 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Oviatt, S.; Schuller, B.; Cohen, P.; Sonntag, D.; Potamianos, G. The Handbook of Multimodal-Multisensor Interfaces, Volume 1: Foundations, User Modeling, and Common Modality Combinations; Morgan & Claypool: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, J.; Cardoso, P.; Monteiro, J.; Figueiredo, M. Handbook of Research on Human-Computer Interfaces, Developments, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Common Sense Suggestions for Developing Multimodal User Interfaces. 2016. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/mmi-suggestions/ (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Havik, E.M.; Kooijman, A.C.; Steyvers, F.J. The effectiveness of verbal information provided by electronic travel aids for visually impaired persons. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2011, 105, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebiyi, A.; Sorrentino, P.; Bohlool, S.; Zhang, C.; Arditti, M.; Goodrich, G.; Weiland, J.D. Assessment of feedback modalities for wearable visual aids in blind mobility. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, S.V.; MacKenzie, I.S. Comparison of Feedback Modes for the Visually Impaired: Vibration vs. Audio. In International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 420–432. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel, J.; Velleman, E.; van der Geest, T. Developing accessibility design guidelines for wearables: Accessibility standards for multimodal wearable devices. In International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Hufschmidt, M. Human factors (hf): Multimodal interaction, communication and navigation guidelines. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Human Factors in Telecommunication, Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1–4 December 2003; European Telecommunications Standards Institute: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2003; Volume 1, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lahat, D.; Adali, T.; Jutten, C. Multimodal data fusion: An overview of methods, challenges, and prospects. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 1449–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjoreski, H.; Ciliberto, M.; Wang, L.; Ordonez Morales, F.J.; Mekki, S.; Valentin, S.; Roggen, D. The University of Sussex-Huawei Locomotion and Transportation Dataset for Multimodal Analytics With Mobile Devices. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 42592–42604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouat, S.B.S.C.J. CREATE: Multimodal Dataset for Unsupervised Learning and Generative Modeling of Sensory Data from a Mobile Robot. IEEE Dataport 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Wang, K.; Bai, J.; Xu, Z. OpenMPR: Recognize places using multimodal data for people with visual impairments. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2019, 30, 124004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspo, A.; Wersényi, G.; Jeon, M. A survey on hardware and software solutions for multimodal wearable assistive devices targeting the visually impaired. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2016, 13, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Liljedahl, M.; Lindberg, S.; Delsing, K.; Polojärvi, M.; Saloranta, T.; Alakärppä, I. Testing two tools for multimodal navigation. Adv. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallacher, S.; Papadopoulou, E.; Taylor, N.K.; Williams, M.H. Learning user preferences for adaptive pervasive environments: An incremental and temporal approach. ACM Trans. Auton. Adapt. Syst. TAAS 2013, 8, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Han, S. A model of machine learning based on user preference of attributes. In International Conference on Rough Sets and Current Trends in Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 587–596. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, B.; Zhao, H. Predictors of assistive technology abandonment. Assist. Technol. 1993, 5, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).