Design of Digital Interaction for Complex Museum Collections

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Digital Technologies for Museum Exhibits

1.2. Design Strategies for Digital Museums

- ARCO (Augmented Representation of Cultural Objects) for the first time provided a complete solution for the digitization, management and the presentation of virtual museum exhibitions, addressing visualization in interactive VR and AR interfaces by adopting a component-based approach and supporting the mixing and matching of individual components through the use of the Extensible Markup Language (XML) for interoperability purposes [26];

- CHESS (Cultural Heritage Experiences through Socio-personal interactions and Storytelling) researched, implemented and evaluated an innovative conceptual and technological framework to integrate interdisciplinary research in personalization and adaptivity, digital storytelling, interaction methodologies, and narrative-oriented mobile and mixed-reality technologies [27]. The current interactive visit at the Athens acropolis, for example, is based on this system;

- EMOTIVE was the evolution of CHESS, based on the premise that cultural sites are highly emotional places. In the framework of this project, the consortium has researched, designed, developed and evaluated methods and tools that can support cultural and creative industries in creating narratives and experiences focused on the emotional storytelling of cultural objects [28];

- MESCH (Material EncounterS with digital Cultural Heritage) investigated the design and use of tangible smart replicas to interact with digital content within a museum exhibition. These smart replicas are used to access additional layers of content that complement the traditional information provided about objects in a museum [29].

2. Methodology

2.1. Complex Museum Collections

- Low—the group is formed by entirely unrelated objects, whose grouping is justified by the mere function or symbolism that they represent rather than each object’s mutual relationship with the others. An example of this kind is the collection of the “Museum der Dinge” (Museum of Things) in Berlin (https://www.museumderdinge.org). The readability of the collection is implicit in the objects themselves;

- Medium—the grouped selection of objects follows the general criteria, such as belonging to the same civilization, historical period, artistic or cultural movement, that makes it somehow homogeneous. In this case, a moderate number of semantic interconnections among the members could be present (e.g., paintings created by the same artist, different sculptural representations of the same divinity, etc.). Some complementary explanations should help the readability of this level of complexity;

- High—the group is made of objects strictly interlinked by many semantic connections associated to ICH components that are possibly non-explicit, such as being associated with the same person for specific activities or being used for rituals that connect each one to the others.

2.2. Digital Interaction with CMCs

- Domain experts—these include museum curators and experts in museum content and topics (archaeologists, historians, art history experts, etc.). They provide knowledge about the available assets and possible interpretative keys useful to define the application content;

- Exhibition designers—they are responsible for the set-up of the museum exhibitions, including both the physical cultural heritage assets and also the devices running the digital applications;

- Content designers—they provide the connection framework of the material and immaterial cultural heritage assets; they define the possible paths of the interaction and create the textual contents;

- Digital asset designers—they oversee the digital asset creation and the combination of such assets into interactive activities.

- Tools that need ad hoc space for projections or the recording of user movements (e.g., virtual reality caves, boxes equipped with VR headsets, tracking sensor, etc.);

- Sound and audio effects that could be disturbing the rest of the exhibition;

- Use of the virtual application by individuals or small groups, for a limited time, for not creating gatherings that disturb the flow of other visitors.

3. Case Study

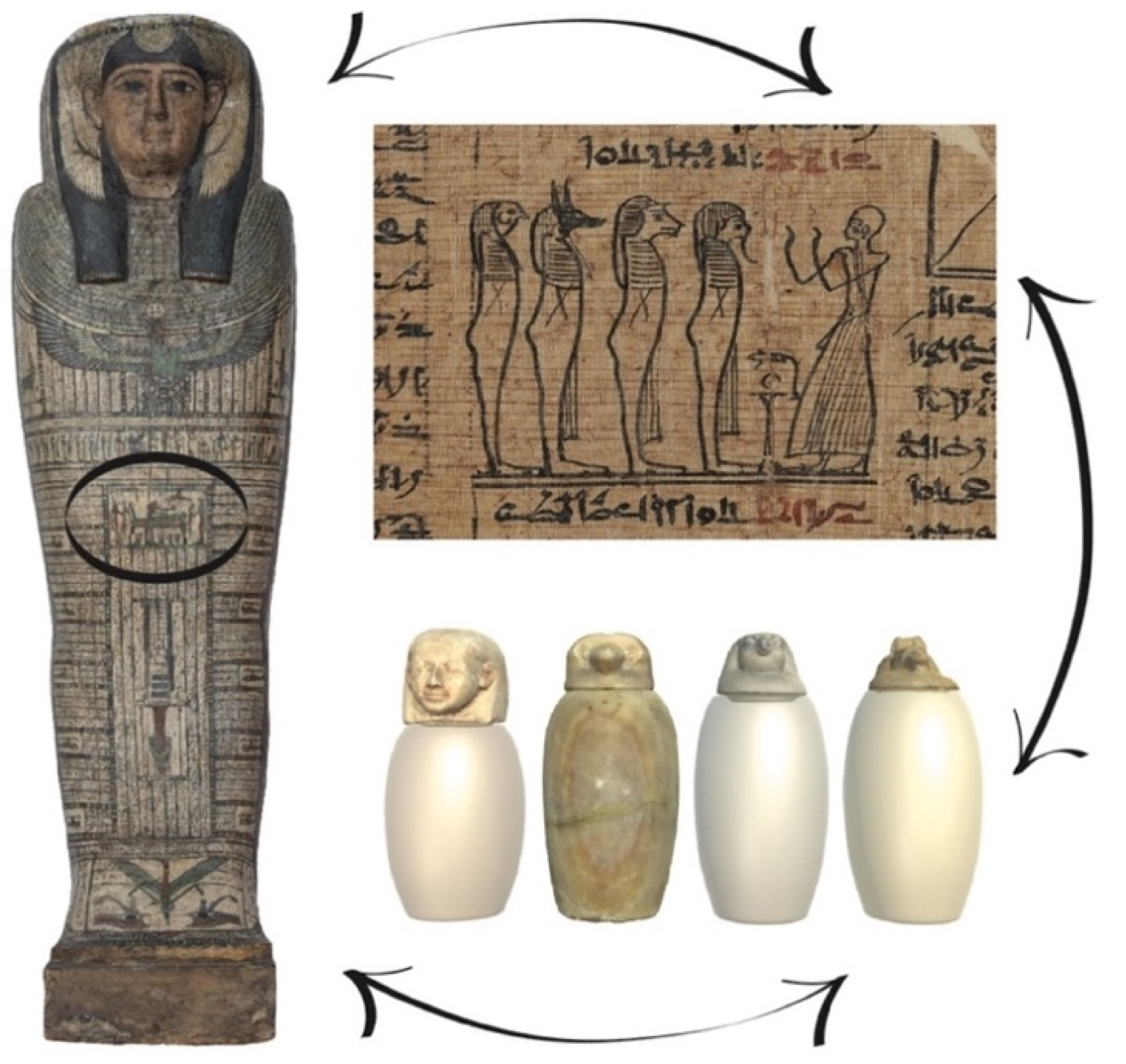

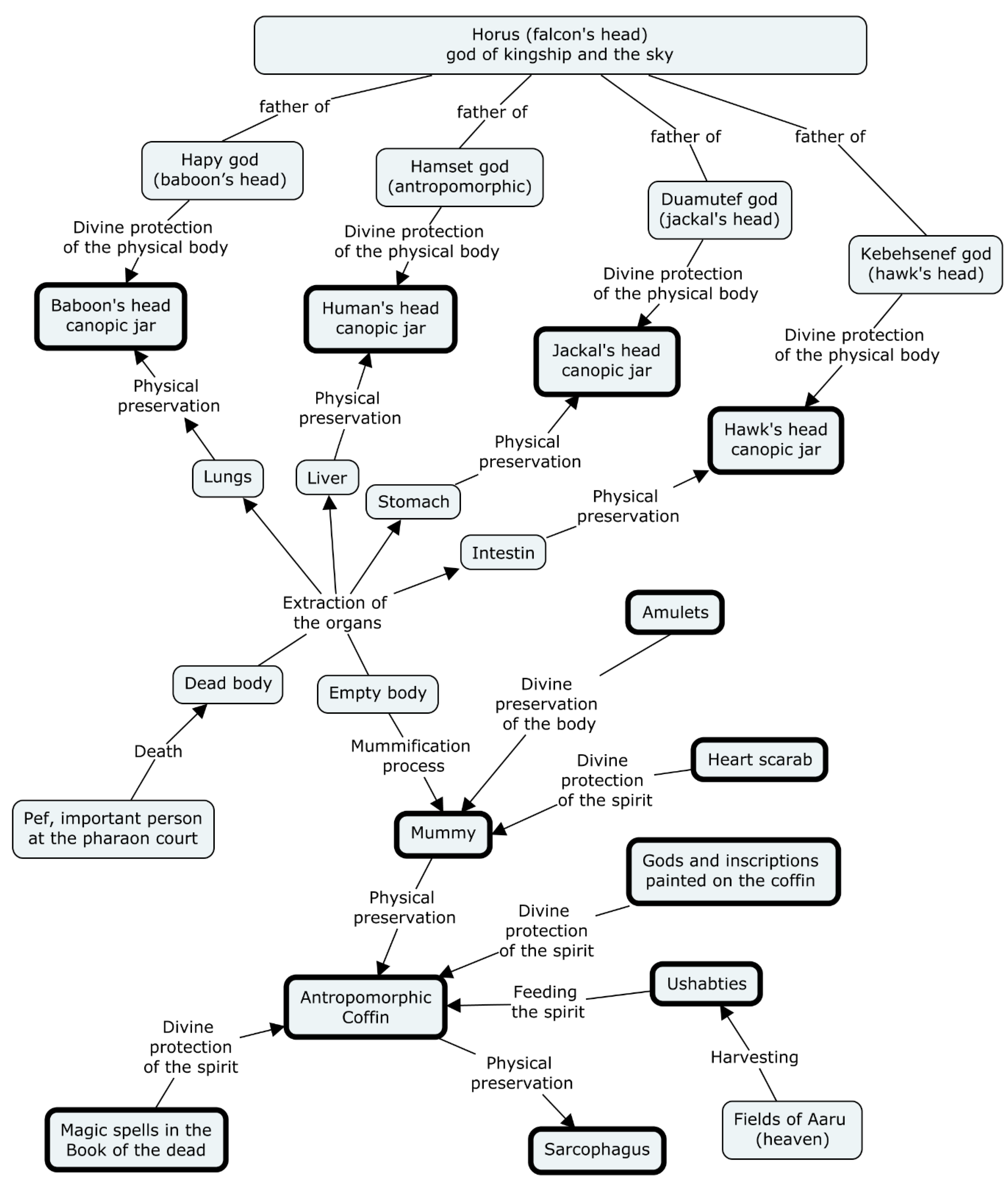

3.1. The Specific CMC

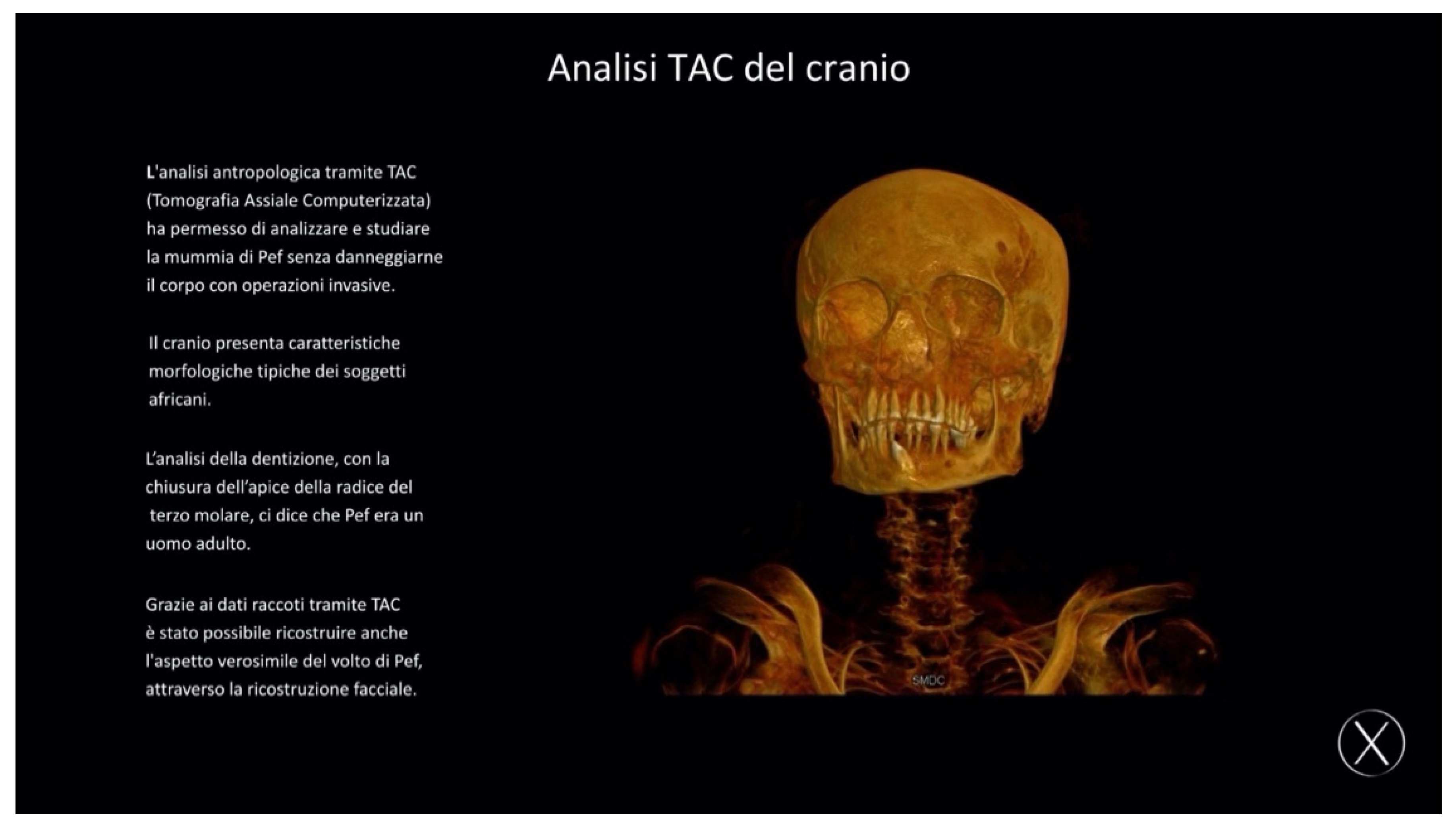

- The mummy of Peftjauauiaset (hereafter “Pef” for short), his painted anthropoid bivalve coffin and the painted sarcophagus used for containing it (7th century BC). Pef was a scribe from Thebes, i.e., a person educated in the arts of writing, that was one of the most prominent figures in the royal court [44];

- The painted anthropoid bivalve coffin of Tesbastetperet (hereafter “Tes” for short), and the related wooden sarcophagus (7th–6th century BC). She was a wealthy woman part of the court: the coffin inscriptions describe Tes as “the lady of the house”;

- Four canopic jars, used for storing the different internal organs of the deceased;

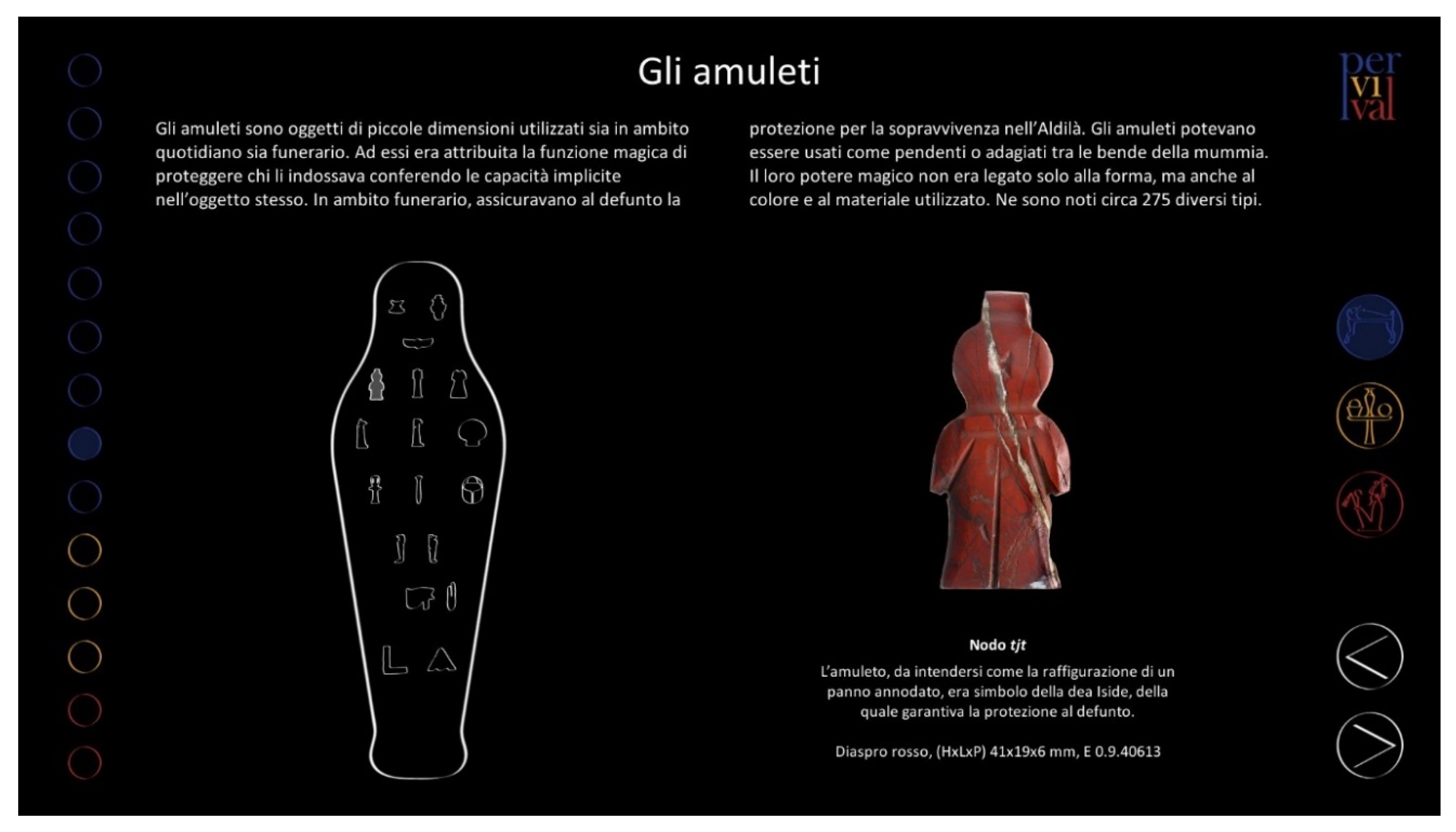

- Eighteen amulets of different types, including the important “hearth scarab,” inscribed with microscopic spells, very difficult to be read under the naked eye when the object is in a showcase;

- A couple of ushabti, representing the hundreds that it is possible to find related to a deceased, and a painted box to store them;

- A false door stele, representing the passage from the Life to Afterlife world;

- A papyrus representing the “book of the dead”, a collection of magic spells intended to assist the deceased during their journey to the Duat. This exemplar belonged to Hornefer, a priest and scribe lived in the Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BC).

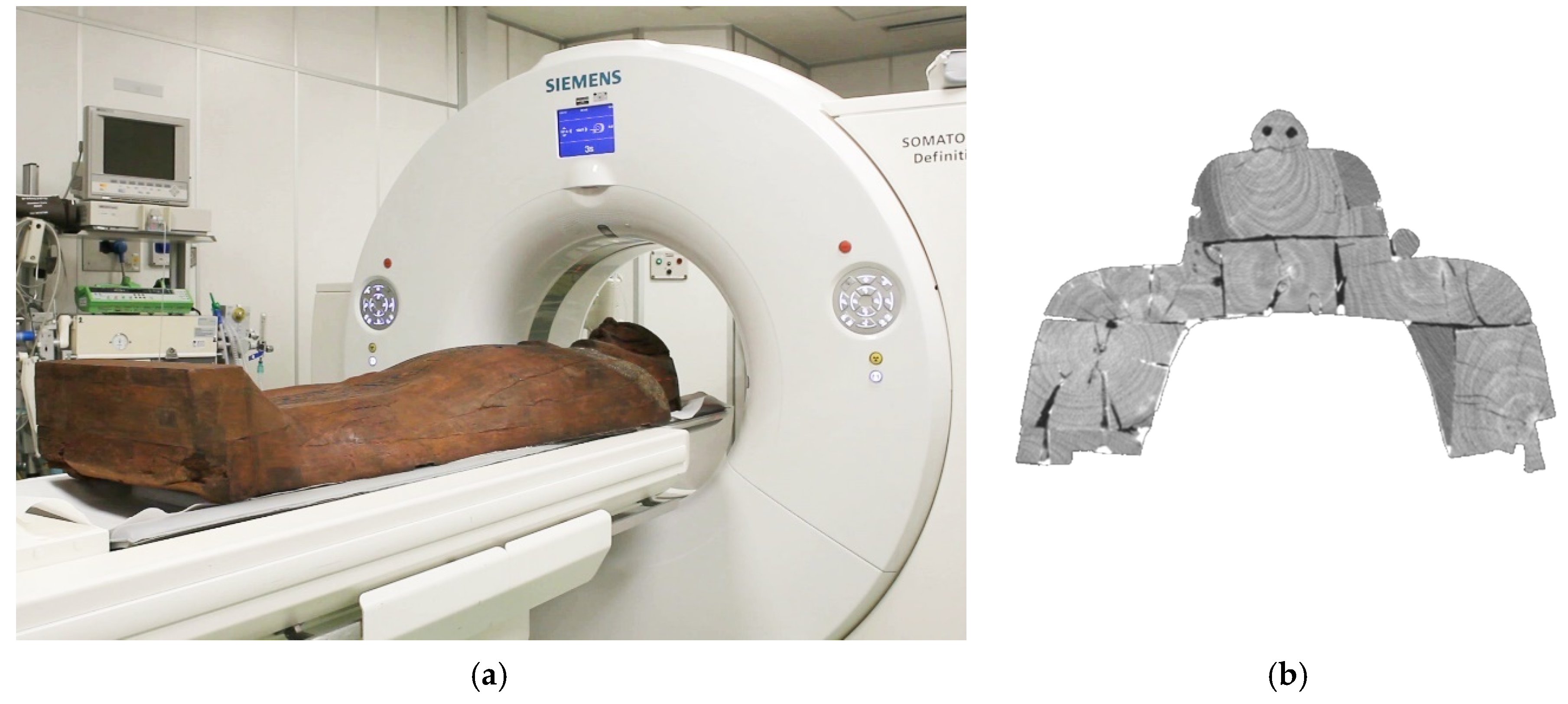

3.2. Digitization

- An APS-C mirrorless camera Sony Alpha 6000 coupled with a Zeiss 24 mm f/1.8 lens;

- A full-frame Canon 5D Mark II digital reflex with two lenses: Canon EF 20mm f/2.8 USM and Canon EF 50 mm f/1.8.

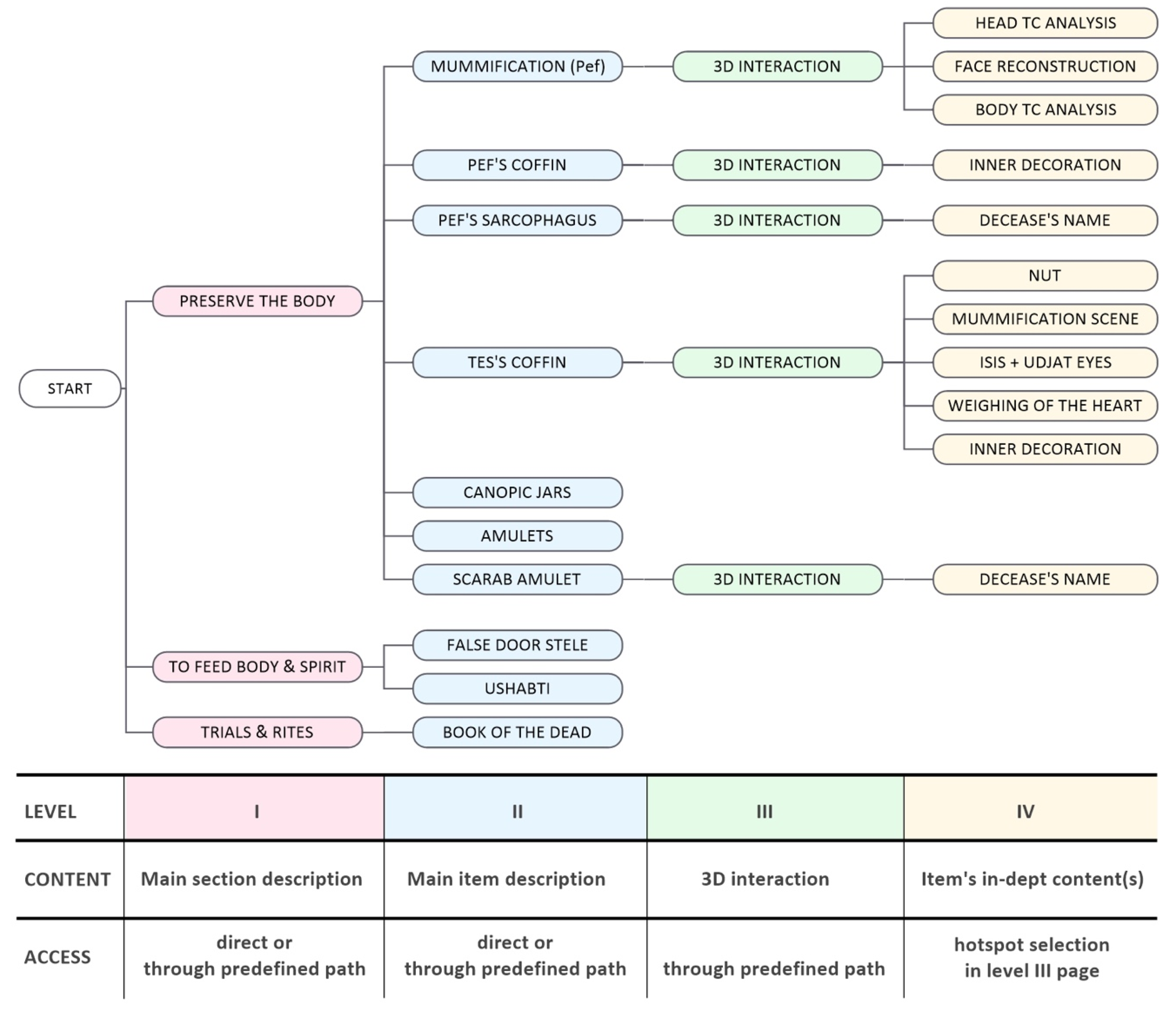

3.3. Interactive Application

- Preserve the intact body through mummification, coffin, sarcophagus, and an appropriate tomb;

- Feed the defunct with real or represented food;

- Face ordeals with the help of rituals, amulets and coffin decorations as described in the papyrus of the “Book of the Dead” that was part of the burial goods.

- Hotspots to allow the user to enable in-depth pages (Level IV) associated to their location on the 3D model. The visualization of these hotspots can be switched through a button;

- A slider to navigate all the perspectives of the introductory animation;

- A magnifying glass to appreciate the details of the 3D model.

- Three minutes for a synthetic overview of the whole material (Level I);

- Twenty to twenty-five minutes for a complete navigation.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Museum Associations. Museums of the World 2019; De Gruyter Saur: Berlin, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-11-063555-3. [Google Scholar]

- ICOM Museum Definition. Available online: https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition/ (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-8147-4281-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, L. Storytelling: The Real Work of Museums. CURA Curator Mus. J. 2001, 44, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R. Museums in a Digital Age; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 0-415-40261-1. [Google Scholar]

- Geismar, H. (Ed.) Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age; UCL Press: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78735-281-0. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, P.; Takemura, H.; Utsumi, A.; Kishino, F. Augmented reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum. SPIE 1995, 2351, 282–292. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele, M.K.; Champion, E. A comparison of immersive realities and interaction methods: Cultural learning in virtual heritage. Front. Robot. AI 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, D. Making virtual reconstructions part of the visit: An exploratory study. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2019, 15, e00123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiourt, C.; Koutsoudis, A.; Pavlidis, G. DynaMus: A fully dynamic 3D virtual museum framework. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 22, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornecker, E.; Ciolfi, L. Human-Computer Interactions in Museums: Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics; Morgan & Claypool: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-68173-513-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, M.; Law, C.; Psihogios, J.; Vanderheiden, G.; Ziebarth, B. Development of accessible kiosk user interface solutions for the public sector: A panel summary. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 8–12 October 2001; pp. 230–234. [Google Scholar]

- Burmistrov, I. Touchscreen Kiosks in Museums. Available online: https://doi.org/10.13140/rg.2.1.4521.0087 (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Carrozzino, M.; Bergamasco, M. Beyond virtual museums: Experiencing immersive virtual reality in real museums. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Morales, J.; Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; De-Juan-Ripoll, C.; Llinares, C.; Guixeres, J.; Iñarra, S.; Alcañiz, M. Navigation comparison between a real and a virtual museum: Time-dependent differences using a head mounted display. Interact. Comput. 2019, 31, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nack, F.; Waern, A. Mobile digital interactive storytelling—A winding path. New Rev. Hypermedia Multimed. 2012, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serravalle, F.; Ferraris, A.; Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A.; Christofi, M. Augmented reality in the tourism industry: A multi-stakeholder analysis of museums. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Ullah, S.; Yan, D.; Rabbi, I.; Richard, P.; Hoang, T.; Billinghurst, M.; Zhang, X. Robust tracking through the design of high quality fiducial markers: An optimization tool for artoolkit. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 22421–22433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vGIS Team 2020 iPad Pro: Does the LiDAR Sensor Improve Spatial Tracking? Available online: https://www.vgis.io/2020/04/23/2020-ipad-pro-does-the-lidar-sensor-improve-spatial-tracking/ (accessed on 30 May 2020).

- Sullivan, M. The Next iPhone will Get a ‘World Facing’ 3D Camera. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/90474966/the-next-iphone-will-get-a-world-facing-3d-camera (accessed on 30 May 2020).

- Kenderdine, S.; Chan, L.K.Y.; Shaw, J. Pure Land: Futures for embodied museography. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2014, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsichritzis, D.; Gibbs, S. Virtual museums and virtual realities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Hypermedia and Interactivity in Museums, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 14–16 October 1991; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Roussou, M. High-End Interactive Media in the Museum. In ACM SIGGRAPH 99 Conference Abstracts and Applications, Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH99: 26th International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 8–13 August 1999; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, A. A Virtual Environment Task-Analysis Tool for the Creation of Virtual Art Exhibits. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1999, 8, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Network of European Museum Organization (NEMO) EU funding and Museums. Available online: https://www.ne-mo.org/fileadmin/Dateien/public/NEMO_documents/NEMO_EU_funding_and_Museums_report.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- White, M.; Chmielewski, J.; Stawniak, M.; Wiza, W.; Patel, M.; Stevenson, J.; Manley, J.; Giorgini, F.; Sayd, P.; Gaspard, F.; et al. ARCO—An architecture for digitization, management and presentation of virtual exhibitions. In Proceedings Computer Graphics International; IEEE: Crete, Greece, 2004; pp. 622–625. [Google Scholar]

- Katifori, A.; Karvounis, M.; Kourtis, V.; Kyriakidi, M.; Roussou, M.; Tsangaris, M.; Vayanou, M.; Ioannidis, Y.; Balet, O.; Prados, T.; et al. CHESS: Personalized Storytelling Experiences in Museums. In Interactive Storytelling; Mitchell, A., Fernández-Vara, C., Thue, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 232–235. [Google Scholar]

- Roussou, M.; Katifori, A. Flow, Staging, Wayfinding, Personalization: Evaluating User Experience with Mobile Museum Narratives. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2018, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M.T.; Dulake, N.; Ciolfi, L.; Duranti, D.; Kockelkorn, H.; Petrelli, D. Using Tangible Smart Replicas as Controls for an Interactive Museum Exhibition. In TEI ’16: Tenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, N.; de Luca, L. Towards a conceptual foundation for documenting tangible and intangible elements of a cultural object. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2016, 3, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. The Order of Things; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-315-66030-1. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, S. Collecting practices. In A Companion to Museum Studies; Macdonald, S., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4051-0839-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, T. Pasts Beyond Memory: Evolution, Museums, Colonialism; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 0-415-24746-2. [Google Scholar]

- Knell, S.J. Museums and the Future of Collecting; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-351-91643-1. [Google Scholar]

- Katifori, A.; Karvounis, M.; Kourtis, V.; Perry, S.; Roussou, M.; Ioanidis, Y. Applying Interactive Storytelling in Cultural Heritage: Opportunities, Challenges and Lessons Learned. In Interactive Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 603–612. [Google Scholar]

- Redford, D.B. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; ISBN 0-19-513821-X. [Google Scholar]

- Foy, S.; Lowry, K.B. Book of the Dead: Becoming God in Ancient Egypt; Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-61491-038-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pinch, G. Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; ISBN 0-19-517024-5. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, C. Amulets of Ancient Egypt; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1994; ISBN 0-292-70464-X. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, H.M. Egyptian Shabtis; Shire: Lexington, MA, USA, 1997; ISBN 0-7478-0301-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lise, G. Museo Archeologico: Raccolta Egizia; Electa: Milan, Italy, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Miatello, L. Examining Texts and Decoration of Peftjauauiaset’s Coffins in Milan. Égypte Nil. Médit. ENIM 2018, 11, 41–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cignoni, P.; Callieri, M.; Corsini, M.; Dellepiane, M.; Ganovelli, F.; Ranzuglia, G. MeshLab: An open-source mesh processing tool. In Proceedings of the 6th Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference, Salerno, Italy, 2–4 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Guidi, G.; Gonizzi Barsanti, S.; Micoli, L.L.; Russo, M. Massive 3D Digitization of Museum Contents. In Built Heritage: Monitoring Conservation Management; Toniolo, L., Boriani, M., Guidi, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 335–346. ISBN 978-3-319-08533-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lucarelli, R. Images of Eternity in 3D. The visualization of ancient Egyptian coffins through photogrammetry. In Altertumswissenschaften in A Digital Age: Egyptology, Papyrology and beyond; Berti, M., Naether, F., Eds.; University of Leipzig: Leipzig, Germany, 2015; pp. 24.1–24.3. [Google Scholar]

- Jackowski, C.; Bolliger, S.; Thali, M.J. Scenes from the past—Common and unexpected findings in mummies from ancient Egypt and South America as revealed by CT. Radiographics 2008, 28, 1477–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonizzi Barsanti, S.; Caruso, G.; Guidi, G. Virtual navigation in the ancient Egyptian funerary rituals. In Proceedings of the 2016 22nd International Conference on Virtual System Multimedia (VSMM), Otranto, Italy, 17 October 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Roussou, M. The Interplay between Form, Story, and History: The Use of Narrative in Cultural and Educational Virtual Reality. In International Conference on Virtual Storytelling: Using Virtual Reality Technologies for Storytelling; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001; pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M. Prototyping practices supporting interdisciplinary collaboration in digital media design for museums. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2015, 30, 394–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, J.A.G. In Hindsight: Complexity, Contingency, and Narrative Mapping. In Narrative Complexity: Cognition, Embodiment, Evolution; Grishakova, M., Poulaki, M., Eds.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2019; pp. 414–436. ISBN 978-0-8032-9686-2. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, N. The Partecipatory Museum; Museum 2.0: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-615-34650-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, B.C.; Cavallaro, F.; Cl, L.; Gottlieb, H. A Cultural Experience Room: An Interdisciplinary and Inclusive Approach to Visualising Intangible Heritage. In Engaging Spaces: Interpretation, Design and Digital Strategies; Muzeum of King Jan III’s Palace at Wilanow: Poznan, Poland, 2014; pp. 306–319. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, A.; Martí, A. New Storytelling for Archaeological Museums Based on Augmented Reality Glasses. In Communicating the Past in the Digital Age; Hageneuer, S., Ed.; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 85–100. ISBN 978-1-911529-84-2. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, M.C.R.; Tatzgern, M.; Langer, T.; Wenzel, J.W. Augmented Reality Brings the Real World into Natural History Dioramas with Data Visualizations and Bioacoustics at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Curator Mus. J. 2019, 62, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falvo, P.G.; Manera, G.V.; Zoss, J. Conversation with Daniel Goleman about the relationship between the person viewing art and the art itself. Stud. Digit. Herit. 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Micoli, L.L.; Caruso, G.; Guidi, G. Design of Digital Interaction for Complex Museum Collections. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4020031

Micoli LL, Caruso G, Guidi G. Design of Digital Interaction for Complex Museum Collections. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2020; 4(2):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4020031

Chicago/Turabian StyleMicoli, Laura Loredana, Giandomenico Caruso, and Gabriele Guidi. 2020. "Design of Digital Interaction for Complex Museum Collections" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 4, no. 2: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4020031

APA StyleMicoli, L. L., Caruso, G., & Guidi, G. (2020). Design of Digital Interaction for Complex Museum Collections. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 4(2), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4020031