Abstract

Educational innovation is a reality that is present in learning spaces. The use of emerging methodologies such as gamification and flipped learning has shown great potential in improving the teaching and learning process. This study aims to analyze the effectiveness of innovative mixed practices, combining gamification and flipped learning in the subject of Spanish Language and Literature against the isolated use of flipped learning. For this, a quasi-experimental design of descriptive and correlational type, based on a quantitative methodology has been carried out. For its development, two study groups (control-experimental) have been set up. The selected sample is of an intentional nature and was composed of 60 students of the fourth year of Secondary Education of an educational center in Southern Spain. The data has been collected through a validated questionnaire. The results determine that the complement of gamification in flipped learning has led to improvements in various academic indicators. It is concluded that the development of gamified actions in the face-to-face phase of flipped learning improves the motivation, interaction with teachers, and interactions of students.

1. Introduction

At present, changes occur at an extreme speed, something unusual in the history of mankind. This occurs at many levels, affecting most of them throughout society. Among these advances, the irruption of information and communication technologies (ICT), which have become part of the daily evolution of society, is worth mentioning [1].

Education, as a fundamental value of human development, is also affected by the progress and inclusion of these tools in it, both for teaching [2] and for the learning of 21st century students [3]. These actions are carried out to update the didactic processes and, turning them into innovators, to adapt them to the usual life of the students [4].

Schools, in recent years, have been developing a transformation in teaching, led by the use of technology that is available to all members of the school community [5]. Because of this, there has been an improvement in the quality of teaching actions, resulting in an increase in values such as motivation and, in addition, making available to all a wide range of technological resources at the service of teaching action [6,7]. Students also see their interest in educational action increased as long as information and communication technologies (ICT) are available, and their use is provoked [8], leading to better access of these to training and content [9].

Therefore, it can be said that ICTs are fundamental in educational development at this time [10], specifically in the teaching and learning processes that want to adapt to the changes of today’s society [11]. In addition, not only do the processes change, but also the spaces dedicated to learning [12], which causes new experiences around learning [13]. The goal of all these changes, as it cannot be otherwise, has quality as the fundamental axis, understood as adaptation of education to the digital era [14]. In addition, the application of these technologies gives rise to the emergence of new methodologies in relation to education.

In relation to the emergence of new methods and techniques for teaching, there are endless names that fit what society demands at the moment and the concerns of students. Proving this and to promote autonomy in access to content and the investment of spaces and times in learning, flipped learning arose [15]. This approach consists of making the contents available to students in an audiovisual way, so that they can access them and personalize their learning in other spaces outside of the school environment and before the face-to-face session where the contents will be worked from a more practical perspective [16]. Flipped learning has acquired, in a very short time, a wide popularity, being carried out at all educational levels due to its effectiveness and its practicality in the teaching and learning processes [17,18,19].

The key to the increasing implementation of flipped learning as an instructional method is based on the use of free time for students to provoke their interaction with the contents [20]. For this, the relevant digital platforms and tools are established by the teacher [21,22,23]. This investment referred to in this methodology lies in making use of the student’s teaching schedule to develop didactic actions based on the previous experience of the student, who has already interacted with the contents autonomously on the platforms established for this purpose [24,25,26]. This causes a growing motivation in the students as well as a greater interaction by all the actors in the educational process [27,28].

Consequently, we can consider that flipped learning is an effective educational method, increasing values such as commitment by students [29], expanding their participation fees [30], and motivating them above average values [31]. It improves self-control and regulates the individual learning of the subjects who receive the teaching [32]. It turns the student into their own learning rhythm regulator [33]. All this, in addition, causes relations to be more fluid, and socialization between peers and between students and teachers is increased [34,35,36], which in turn causes better predisposition to solving problems posed in the learning process [37].

These values that are increased, directly intercede with the learning outcomes [38], causing better student ratings [39], better acquisition of the skills and objectives of learning [40,41,42], and a mostly positive reaction in relation to the formative process [43]. Therefore, flipped learning can be understood as a highly effective techno-pedagogical approach to traditional teaching [44,45,46].

During the last years, the modifications carried out in the traditional methodologies have been based on considering games as a fundamental axis of the student’s development. Taking its mechanisms, learning can be adapted and facilitated to the interests of students, thus achieving a better understanding of the contents to be assimilated [47]. The development of this strategy arises from the need of humans to play, trying to promote free and voluntary participation in a world of codes and norms [48].

Gamification is a term that arises from the business world, with the idea of customer loyalty [49] and that bases its main function on the application of game-inspired mechanics, in the formal context of teaching [50,51].

The implementation of gamification in educational practice leads to the increase of multiple benefits related to education, since it presents the activities as an attractive challenge to students [52,53,54,55], helps them solve problems [56], increases the level of commitment to the task [57,58], and increases the interest in learning [59]. With this, in addition, there is an increase in interest that leads to the promotion of the acquisition of skills [60], as well as an improvement in social skills [61] and the behavior of students [62,63].

Undoubtedly, the application of gamification as a didactic strategy causes an increase in the positive values of student development, taking into account the change of rewards for the typical qualifications [64], giving students freedom in the training process, eliminating their fears of making mistakes, and making them the protagonists of the follow-up of their training [65].

On the other hand, the flipped learning methodology and the gamified approach have been used more frequently in recent years for the promotion of linguistic competence in the language and literature classroom.

Many investigations have found that the flipped learning methodology contributes specifically to linguistic competence compared to other traditional teaching models [66]. The promotion of linguistic competence with the flipped learning methodology is especially enhanced if its application is produced through a three-stage design to plan, apply, and reproduce the approach transversely [67]. The main skills that are enhanced in the language and literature classroom with the flipped learning methodology are those related to motivation, self-regulation, autonomy, critical thinking, creativity, decision making, interaction (with students and teachers), individualization, use of classroom time, and achievement of learning objectives [68].

Likewise, the gamified approach has also been analyzed in several studies that have stated its positive aspects for the practice of linguistic competence. One of the most attractive aspects of gamification in the language classroom is the motivation and participation of students [69,70]. In addition, gamification favors attitudinal aspects in the language classroom, such as student commitment and self-efficacy [71], and other, more specific skills, such as grammar, vocabulary, and oral and written language and competence performance [70].

Justification, Objective, and Research Questions

Given the importance and projection of educational innovation in learning spaces, promoted by the inclusion of ICT and the various emerging training methodologies (gamification and flipped learning), as well as the potential offered to the teaching and learning process, this study was carried out with the purpose of inquiring about the benefits of using the active and innovative instructive approaches mentioned. In addition, this research aims to continue with the path already initiated by other researchers who revealed the advantages of these active methodologies in the formative action along with various incident factors [16,17,18,19,45,46,68,72,73,74].

The research took place in the fourth year of Secondary Education with the intention of reducing the possible bias of an inadequate familiarization with digital resources and tools, because at these levels the students present an adequate digital competence, encouraged by the incidence of technology in society [75].

The general objective formulated in this research focuses on analyzing the effectiveness of innovative mixed practices, combining gamification and flipped learning in the subject of Spanish Language and Literature against the isolated use of flipped learning. From this objective, the following research questions (RQ) are posed:

- RQ1: Does the incorporation of gamified tasks influence the face-to-face part of flipped learning in student motivation?

- RQ2: Does it influence the interaction between the student and the teacher?

- RQ3: Does it influence the interaction between students?

- RQ4: Does it influence the interaction between the student and the contents?

- RQ5: Does it influence the student collaboration?

- RQ6: Does it influence the deepening of didactic contents?

- RQ7: Does it influence problem solving by students?

- RQ8: Does it influence class time?

- RQ9: Does it influence the ratings achieved by students?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Data Analysis

The study was carried out through a quasi-experimental design of a descriptive and correlational type, based on a quantitative methodology of data processing. For its effective development, the guidelines established by experts in this type of research were followed [76,77]. In addition, the structure of previous studies of the same investigative nature, reported from impact journals indexed in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR), was followed as a validated model [68,78,79,80].

The experiment was carried out with two study groups (1-Control and 1-Experimental), establishing the training methodology as an independent variable and the effectiveness obtained in the different academic aspects to be evaluated as a dependent variable.

The data collected was analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v25 program (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistics such as mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were used, and other, more specific tests such as skewness (Skew) and kurtosis (Kurt) were carried out to obtain the distribution trend. The t-Student test was performed to compare the means between the control and the experimental group. Cohen’s d and biserial correlation (r) were applied to reveal the size of the effect caused. We worked with a level of significance of p < 0.05 in the statistical analysis.

2.2. Participants

In the experiment, 60 students of the fourth year of Secondary Education of a Spanish educational center participated. The study subjects were selected in a non-probabilistic manner with intentional sampling, given the ease of access to said sample. Experts reveal that the sample size in this type of studies does not condition its performance [81,82].

These participants, socio-demographically, make up a sample with 31.6% of men and 68.3% of women, with an average age of 16 years (SD = 1.14). These students have been divided into two analysis groups (Control and Experimental). Specifically, a treatment (methodological combination = gamification and flipped learning) was applied randomly in one group, taking a single measurement in both (Table 1).

Table 1.

Group composition.

2.3. Instrument

A questionnaire was the instrument selected for data collection (Table S1). This instrument was designed taking other questionnaires reported from the literature as a reference [16,68,79,83,84,85].

The questionnaire used is articulated in various dimensions (Socio-educational, Motivation, Cooperation, Autonomy, Problem solving, Interaction teacher, Interaction classmates, Interaction contents, Class time, Linguistic competence, and Ratings) with a total of 42 items on a Likert scale (from 1 = None to 4 = Completely).

The instrument used underwent a validation process, first by Delphi method composed of eight experts who revealed a favorable, relevant, and concordant opinion of the tool (M = 4.27; SD = 0.56; min = 1; max = 6; Fleiss’ Kappa = 0.81; Kendall’s W = 0.84). In addition, these specialists offered feedback focused on the reduction of items and modification of the lexicon to improve the data collection process and reduce possible biases. Moreover, the questionnaire went through an exploratory factor analysis by the principal components method. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity resulted in dependence between the variables (2582.31; p < 0.001), and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test revealed a correct sample adequacy (KMO = 0.85).

Various statistical tests were performed to achieve the reliability of the instrument. Specifically, Cronbach’s alpha (α) (0.87), compound reliability (0.83), and mean variance extracted (0.82) were calculated, determining a relevant internal consistency of the tool.

2.4. Procedure

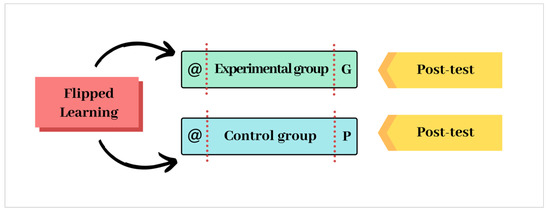

The deployment of this study was carried out in several processes. First, the educational center and the corresponding level of the students were selected. Second, a didactic unit of eight sessions was held in the subject of Spanish Language and Literature, the contents of which are the following: (a) simple sentence syntactic functions; (b) syntactic analysis for compound sentences; (c) analysis of the particularities of sentences. Methodologically, the teaching unit was taught in two different ways according to the group of students. The assignment of the group typology was assigned randomly, without any contingency, since the educational center has two groups per level. Specifically, the methodology used in each group was based on flipped learning. The difference was found in the experimental group, whose face-to-face learning phase was energized by gamified activities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological procedure. Note. @ = Digital learning phase; P = Face-to-face learning phase; G = Gamified activities.

The gamification implemented was a gamification of content (superficial type) because this approach was applied exclusively for the didactic unit treated. The free tool PeerWise (https://peerwise.cs.auckland.ac.nz/) was used for the implementation of the gamified approach. The teacher requested the creation of an account to use the resource, which allowed creating the course and managing student access. This digital tool gave the student self-management capacity, who autonomously organized their learning process. The learning was carried out from the creation of questions by the students, promoting cooperative learning and collaboration, since the tool allows continuous interaction with peers, the possibility of commenting on the questions and offering answers. This training context was complemented by the creation of learning levels, scoring systems, badge boards, and player reputation rankings. Finally, the teacher’s feedback was carried out throughout the learning process.

Once the didactic unit was taught, the students filled out a questionnaire to extract the information related to the different dimensions proposed. Finally, the data collected were treated at a statistical level in order to effectively answer the various research questions and, consequently, achieve the objective of the research.

3. Results

The following paragraphs analyze in detail the results obtained in the parametric analysis of the results reported by the control group and by the experimental group. The values of the mean and the totalization of each dimension are assessed, and the analysis of the value of intergroup independence is established.

Regarding the parametric analysis of the study groups (Table 2), the results reflect relatively similar scores. The use of the flipped learning methodology allowed to overcome the central score (M ≥ 2.5) in practically all the analyzed dimensions, independently of the study group. Despite this, students who received a flipped learning methodology supplemented with gamification (experimental group) obtained slightly higher scores than students who followed a traditional flipped learning methodology (control group). The dimension related to motivation has been the dimension that has reached higher values in both study groups. Likewise, the highest values obtained in the traditional flipped learning methodology are those related to the ability to interact with the learning contents. On the other hand, the highest values obtained in the flipped learning methodology complemented with gamification are those related to the interaction with classmates.

Table 2.

Parametric analysis of the results reported in both groups (control and experimental).

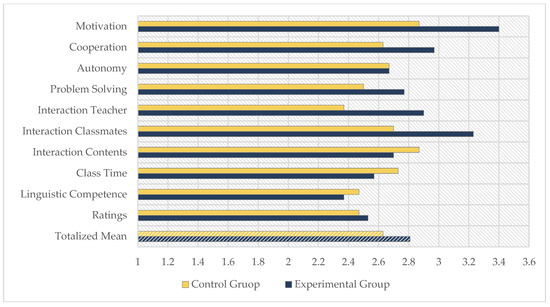

Furthermore, Figure 2 shows the average scores obtained in each dimension by both groups. The most significant differences are observed in the dimensions related to motivation and socialization interactions (teacher and classmates). In all other dimensions, intergroup differences are minimal. The control group records slightly higher scores than the experimental group in the dimensions related to access and interaction to learning contents, with the use of class time and with the contribution of the methodology to linguistic competence. In summary, the value of the totalized average shows that the flipped learning methodology complemented with gamification (Me = 2.81) obtains average values higher than the traditional flipped learning (Me = 2.63).

Figure 2.

Comparative intergroup analysis between the means obtained by both groups.

Finally, the Student’s t-test was carried out to analyze the value of intergroup independence between the results obtained by using a traditional flipped learning methodology and by using the flipped learning approach complemented with gamification (Table 3). The standardized value of p < 0.05 as a statistically significant difference was established. Regarding the comparative evaluation of the results, this analysis establishes three levels of correlation regarding the strength of association (d) and the corrective value (r): low (d < −0.3; r < −0.2), medium (d = [−0.3, −0.8]; r = [−0.2, −0.5]), and high (d > −0.8; r > −0.5).

Table 3.

Intergroup independence value analysis (control and experimental).

Although the values obtained by the flipped learning methodology complemented with gamification are higher—in almost all dimensions—than those obtained by the traditional flipped learning methodology, only values of significance in three dimensions were obtained. Therefore, the analysis reflects significance values with a medium strength of association in the dimensions related to student motivation during the teaching and learning process (d = −0.54; r = 0.26), the interaction with the teacher in the development of gamified learning (d = −0.56; r = −0.28), and socializing interaction with classmates (d = −0.58; r = −0.28).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Innovative practices such as flipped learning and gamification, used independently, have revealed in the scientific literature various potentialities that have a positive impact on the teaching and learning processes. This study focuses on analyzing the effectiveness of innovative mixed practices, combining gamification and flipped learning in the subject of Spanish Language and Literature against the isolated use of flipped learning.

The results obtained in the study determine that aspects such as student–teacher interaction and student–partner interaction were improved through the combined approach. These results are in line with other reported studies that verify how gamification and inverted learning contribute to the benefit of the interrelationships between the agents that participate in the teaching and learning process [20,27,28,31,52]. The use of technological means and digital platforms favor the approach between the student and the teacher [34,35,36] in addition to allowing an increase in relationships between classmates within cooperative and collaborative learning [27,34].

Another element of learning that was very positive was the motivation of the students. Increased motivation during the use of gamification and flipped learning in the teaching and learning process has been a common subject of study in recent years, with highly positive results being found in most of the relevant studies. These studies are related to the role of the student in the training process [27,28], active participation [69,70], and the use of interactive and recreational platforms [24,25,26].

Other dimensions evaluated such as cooperation and problem solving were favored during the combined application of gamification and flipped learning, although no statistical significance was found. These findings are in analogy with previous studies on the status of the issue where values in these dimensions were increased [16,68,72,75,78]. Cooperation and problem solving are two areas of the teaching and learning process that are favored when carried out together. Cooperative learning enables learners to gain new perspectives on tackling issues from different points of view. Based on the benefits presented, it is pertinent that the results obtained by the students analyzed were very positive regarding the ratings. In a similar way to other studies in the scientific literature, it was found that the combined use of flipped learning and gamification allows obtaining better ratings for students [38,39]. The cause of this improvement in grades is mainly related to the optimization in the acquisition of skills and the achievement of learning objectives [40,41,42].

Based on the analysis of the scientific literature, it has been found that the inverted learning methodology and the gamified approach have been used more frequently in recent years for the promotion of linguistic competence in the language and literature classroom. The results obtained in this study coincide with those found in other studies in relation to the potential of both methodological tools for the improvement of motivation, participation, and language skills in the competence practice of the language and literature classroom [66,67,68,69,70,71]. The use of technological tools and innovative approaches allow students to understand abstract concepts that are often abundant in the study of linguistics. In line with what was stated by other authors, when the contents are presented in a motivating and dynamic way [20,28,31], the assimilation of the contents related to the literature is carried out more effectively.

Although the results obtained in the combination of the flipped learning methodology and gamification were positive, there are two specific dimensions in which the results were lower than the rest. The results obtained in the study regarding the possibilities offered by gamification in flipped learning for interaction with the learning content were slightly negative compared to traditional teaching methodology. These results are contrary to those stipulated by the scientific literature, which affirm that this type of methodological action allows the students a greater assimilation of the contents [47], since they are presented as an attractive challenge for the students [52,53,54,55]. On the other hand, the combination of gamification with flipped learning methodology is not particularly positive for the use of class time. Despite the fact that the scientific literature has highlighted that the investment of learning moments and the management of free time favors the use of time [15,20], the results obtained in this study reflect that there is no relevant difference with respect to the traditional teaching methodology. Among other factors, this fact may be related to the lack of attention that excessive use of technological devices can generate in students and to the fact that self-management and autonomy in some students could be difficult.

The application of the flipped learning methodology is especially favorable for student motivation, the promotion of cooperation, the ability to solve problems, and to autonomously deal with interactions with the agents involved in the classroom (teacher and classmates), access to and the interaction with the contents, the use of time in the classroom, the promotion of entrepreneurial competence, and the improvement of qualifications. The use of gamification as a complementary approach during the application of flipped learning allows to maintain optimum levels in the aforementioned areas, in addition to profusely enhancing student motivation, interaction with the teacher, and socializing interaction with classmates. Therefore, gamification is a methodological factor that positively affects the application of the flipped learning approach during the teaching and learning process. For all of the above, this study confirmed that flipped learning is positioned as a highly favorable methodology in the teaching and learning process, especially when combined with a dynamic approach such as gamification.

Regarding the limitations of the research, this study is an exploratory analysis, which makes it impossible for the results to be generalized. It is intended to initiate a field of research that presents a significant deficit of scientific literature, since the number of investigations that analyze the incidence of gamification in the flipped learning approach is very low. Although the sample size limits the possibility of generalizing the results, this study can serve as a starting point for further research on the application of flipped learning in a combined or complemented manner. Moreover, since it is an exploratory study, it has been very difficult to compare the results obtained in this analysis with the results of other studies that deal with this topic and specifically analyze gamification as a complement to inverted learning.

To continue the research line initiated in the present study, it is proposed to perform a SWOT analysis that assesses strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. The realization of the SWOT matrix will allow to optimize the complementation of the flipped learning methodology through gamification, and the results obtained in a sample of similar characteristics to those of this study can be evaluated again. Likewise, it is proposed to check the effects of other complementary approaches to flipped learning methodology, such as project-based learning (PBL), design thinking (DT), cooperative learning (CL), or thinking-based learning (TBL).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2414-4088/4/2/12/s1, Table S1: QUESTIONNARIE CONEXP019FLGM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.B., A.F.C. and J.A.L.N.; methodology, J.L.B. and S.P.S.; software, S.P.S.; validation, S.P.S. and J.A.L.N.; formal analysis, J.L.B. and J.A.L.N.; investigation, J.L.B., A.F.C., J.A.L.N. and S.P.S.; data curation, S.P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.B. and A.F.C.; writing—review and editing, J.L.B. and S.P.S.; visualization, A.F.C.; supervision, J.A.L.N. and A.F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the researchers of the research group AREA (HUM-672), which belongs to the Ministry of Education and Science of the Junta de Andalucía and registered in the Department of Didactics and School Organization of the Faculty of Education Sciences of the University of Granada.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maldonado, G.A.; García, J.; Sampedro-Requena, B. The effect of ICT and social networks on university students. RIED 2019, 22, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Sukhbaatar, J.; Takada, J. The Influence of Teachers’ Professional Development Activities on the Factors Promoting ICT Integration in Primary Schools in Mongolia. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrote, D.; Arenas, J.A.; Jiménez-Fernández, S. ICT as tools for the development of intercultural competence. EDMETIC 2018, 7, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Area, M.; Hernández, V.; Sosa, J.J. Modelos de integración didáctica de las TIC en el aula. Comunicar 2016, 24, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Fillol, J.; Moura, P. El aprendizaje de los jóvenes con medios digitales fuera de la escuela: De lo informal a lo formal. Comunicar 2019, 1, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Rodríguez, M.D.; Bellido-Márquez, M.D.; Atencia-Barrero, P. Teaching though ICT in Obligatory Secundary Education. Analysis of online teaching tools. RED 2019, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khine, M.S.; Ali, N.; Afari, E. Exploring relationships among TPACK constructs and ICT achievement among trainee teachers. Educ. Infor. Technol. 2017, 22, 1605–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Quintero, J.L.; Pontes-Pedrajas, A.; Varo-Martínez, M. The role of ICT in Hispanic American scientific and technological education: A review of literature. Dig. Educ. Rev. 2019, 1, 229–243. [Google Scholar]

- Mat, N.S.; Abdul, A.; Mat, M.; Abdul, S.Z.; Nun, N.F.; Hamdan, A. An evaluation of content creation for personalised learning using digital ICT literacy module among aboriginal students (MLICT-OA). TOJDE 2019, 20, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulou, K.; Akriotou, D.; Gialamas, V. Early Reading Skills in English as a Foreign Language Via ICT in Greece: Early Childhood Student Teachers’ Perceptions. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, J.C.; Sánchez, P.A. Limitaciones conceptuales para la evaluación de la competencia digital. Espacios 2018, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira, F.; Shigueo, E.; Abdala, H. Collaborative Teaching and Learning Strategies for Communication Networks. Int. J. Engi. Educ. 2018, 34, 527–536. [Google Scholar]

- Cabero, J.; Barroso, J. Los escenarios tecnológicos en Realidad Aumentada (RA): Posibilidades educativas en estudios universitarios. Aula Abierta 2018, 47, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, R.E.; Feliciano, A.; Alarcón, A.; Catalán, A.; Alonso, G.A. The integration of ICT tools to the profile of the Computer Engineer of the Autonomous University of Guerrero, Mexico. Virtualidad Educ. Cienc. 2019, 10, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, J.; Sams, A. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day, 1st ed.; ISTE: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- López, J.; Pozo, S.; Fuentes, A.; López, J.A. Creación de contenidos y flipped learning: Un binomio necesario para la educación del nuevo milenio. REP 2019, 77, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Holton, A.; Farkas, G.; Warschauer, M. The effects of flipped instruction on out-of-class study time, exam performance, and student perceptions. Learn. Instr. 2016, 45, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Pozo, S.; del Pino, M.J. Projection of the Flipped Learning Methodology in the Teaching Staff of Cross-Border Contexts. NAER 2019, 8, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Habiburrahim, H.; Muluk, S.; Keumala, C.M. How do students become self-directed learners in the EFL flipped-class pedagogy? A study in higher education. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengual, S.; López, J.; Fuentes, A.; Pozo, S. Modelo estructural de factores extrínsecos influyentes en el flipped learning. Educ XX1 2020. Available online: http://revistas.uned.es/index.php/educacionXX1/article/view/23840/20031 (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Abeysekera, L.; Dawson, P. Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom: Definition, rationale and a call for research. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 2015, 34, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; Cummins, J.; Waugh, M. Use of the flipped classroom instructional model in higher education: instructors’ perspectives. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2017, 29, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.M.; Ralph, D.L. The Flipped Classroom: A Twist on Teaching. Contemp. Issues Educ. Res. 2016, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Miedany, Y. Flipped learning. In The Flipped Classroom: Practice and Practices in Higher Education, 1st ed.; Reidsema, C., Kavanagh, L., Hadgraft, R., Smith, N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadri, H.O. Flipped learning as a new educational paradigm: An analytical critical study. Eur. Sci. J. 2016, 12, 417–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Halili, S.H. Flipped classroom research and trends from different fields of study. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2016, 17, 313–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, A.; Sánchez, C.; Calderero, J.F. Nuevos modelos tecnopedagógicos. Competencia digital de los alumnos universitarios. REDIE 2017, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.J.; Lai, C.L.; Wang, S.Y. Seamless flipped learning: A mobile technology-enhanced flipped classroom with effective learning strategies. J. Comput. Educ. 2015, 2, 449–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Foon, K.; Kwan, C. Investigating the effects of gamification-enhanced flipped learning on undergraduate students’ behavioral and cognitive engagement. Inter. Learn. Environ. 2018, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyr, W.L.; Shen, P.D.; Chiang, Y.C.; Lin, J.B.; Tsia, C.W. Exploring the effects of online academic help-seeking and flipped learning on improving students’ learning. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2017, 20, 11–23. Available online: https://bit.ly/35RTgeS (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Tse, W.S.; Choi, L.Y.; Tang, W.S. Effects of video-based flipped class instruction on subject reading motivation. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo, R.; Bernardo, A.; Esteban, M.; Sánchez, M.; Tuero, E. Programas para la promoción de la autorregulación en educación superior: Un estudio de la satisfacción diferencial entre metodología presencial y virtual. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 30–36. Available online: https://bit.ly/2HLYrDa (accessed on 20 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Tourón, J.; Santiago, R. El modelo Flipped learning y el desarrollo del talento en la escuela. Rev. Educ. 2015, 1, 196–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez, C.I.; Clunie, C.E. Una mirada a la Educación Ubicua. RIED 2019, 22, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.E.; Woo, H.R. The Impact of Flipped learning on Cooperative and Competitive Mindsets. Sustainability 2017, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; Logan, J.; Waugh, M. Students’ perceptions of the value of using videos as a pre-class learning experience in the flipped classroom. TechTrends 2016, 60, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognar, B.; Sablić, M.; Škugor, A. Flipped learning and Online Discussion in Higher Education Teaching. In The Flipped Classroom: Practice and Practices in Higher Education, 1st ed.; Reidsema, C., Kavanagh, L., Hadgraft, R., Smith, N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, A.; Jaramillo, N.; Hassall, L. Flipping to engage students: Instructor perspectives on flipping large enrolment courses. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 34, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Ross, B.; LaFerriere, R.; Maritz, A. Flipped learning, flipped satisfaction, getting the balance right. Teach. Learn. Inq. 2017, 5, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awidi, I.T.; Paynter, M. The impact of a flipped classroom approach on student learning experience. Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nortvig, A.M.; Petersen, A.K.; Hattesen, S. A Literature Review of the Factors Influencing E-Learning and Blended Learning in Relation to Learning Outcome, Student Satisfaction and Engagement. Electro. J. E-Learn. 2018, 16, 46–55. Available online: https://bit.ly/2W4iMHL (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Yoshida, H. Perceived usefulness of “flipped learning” on instructional design for elementary and secondary education: With focus on pre-service teacher education. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2016, 6, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, T.; Davis, R.O. What affects learner engagement in flipped learning and what predicts its outcomes? British J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, C. A Study on Digital Media Technology Courses Teaching Based on Flipped Classroom. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, T.; Aznar, I.; Romero, J.M.; Rodríguez, A.M. Eficacia del método flipped classroom en la universidad: Meta-análisis de la producción científica de impacto. REICE 2019, 17, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, N.T.; De Wever, B.; Valcke, M. The impact of a flipped classroom design on learning performance in higher education: Looking for the best “blend” of lectures and guiding questions with feedback. Comput. Educ. 2017, 107, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, H.A. La gamificación como estrategia metodológica en el contexto educativo universitario. Real. Reflexión 2017, 44, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovna, I. Four Pillars of Gamification. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 13, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasó i Rius, J. Pere Vergés: Escuela y gamificación a comienzos del s. XX. Apunts 2018, 1, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attali, Y.; Arieli-Attali, M. Gamification in assessment: Do points affect test performance? Comput. Educ. 2015, 83, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, S. Gamification: Making work fun, or making fun of work? Bus. Inf. Rev. 2014, 31, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Hammer, J. Gamification in Education: What, How, Why Bother? Acad.Exch. Q. 2011, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mora-González, J.; Pérez-López, I.J.; Esteban-Cornejo, I.; Delgado-Fernández, M. A Gamification-Based Intervention Program that Encourages Physical Activity Improves Cardiorespiratory Fitness of College Students: The Matrix rEFvolution Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisabarro Marrón, A.M.; Vivaracho, C.E. Gamificación en el aula: Gincana de programación. ReVisión 2018, 11, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Rigby, C.S.; Przybylski, A. The Motivational Pull of Video Games: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. Motiv. Emot. 2006, 30, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K.M. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 12–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.-C.; Hung, C.-M. Effects of the Digital Game-Development Approach on Elementary School Students’ Learning Motivation, Problem Solving, and Learning Achievement. Int. J. Distance Educ. Technol. 2015, 13, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does Gamification Work? A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. In Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 3025–3034. [Google Scholar]

- Groening, C.; Binnewies, C. “Achievement unlocked!”-The impact of digital achievements as a gamification element on motivation and performance. Comput. Human Behavior 2019, 97, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Area Moreira, M.; González González, C.S. De la enseñanza con libros de texto al aprendizaje en espacios online gamificados. Educatio 2015, 33, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotta, C.; Featherstone, G.; Aston, H.; Houghton, E. Game-Based Learning: Latest Evidence and Future Directions, 1st ed.; National Foundation for Educational Research: Slough, UK, 2013; pp. 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Manzano, A.; Almela-Baeza, J. Gamification and transmedia for scientific promotion and for encouraging scientific careers in adolescents. Media Educ. Res. J. 2018, 26, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Ceyhan, P.; Jordan-Cooley, W.; Sung, W. GREENIFY: A Real-World Action Game for Climate Change Education. Simul. Gaming 2013, 44, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Colón, A.-M.; Jordán, J.; Agreda, M. Gamificación en educación: Una panorámica sobre el estado de la cuestión. Educ. Pesqui. 2018, 44, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekler, E.D.; Bruhlmann, F.; Tuch, A.N.; Opwis, K. Towards understanding the effects of individual gamification elements on intrinsic motivation and performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.; Peragón, C.E.; Vara, A.; Jiménez, A.; Muñiz, M.J.; López, M.C.; Leva, B. Flipped “learning”: Aplicación del enfoque Flipped Learning a la enseñanza de la lengua y literatura españolas. Rev. Innovación Buenas Prácticas Docentes 2017, 2, 1–23. Available online: https://www.universidaddecordoba.eu/ucopress/ojs/index.php/ripadoc/article/download/9614/9085 (accessed on 21 February 2020). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jiménez, A.; Domínguez, J. Análisis de la eficacia del enfoque Flipped Learning en la enseñanza de la lengua española en Educación Primaria. Didacticae: Rev. Investig. Didácticas Específicas 2018, 4, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, S.; López, J.; Moreno, A.J.; López, J.A. Impact of Educational Stage in the Application of Flipped Learning: A Contrasting Analysis with Traditional Teaching. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.W.; Fowler, T.A. Gamification of Formative Feedback in Language Arts and Mathematics Classrooms: Application of the Learning Error and Formative Feedback (LEAFF) Model. Int. J. Game-Based Learn. 2020, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotob, M.M.; Ibrahim, A. Gamification: The Effect on Students’ Motivation and Achievement in Language Learning. J. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Res. 2019, 6, 177–198. Available online: http://jallr.com/~jallrir/index.php/JALLR/article/download/951/pdf951 (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Rachels, J.R.; Rockinson-Szapkiw, A.J. The effects of a mobile gamification app on elementary students’ Spanish achievement and self-efficacy. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2018, 31, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A.; Parra, M.E.; López, J.; Segura, A. Educational Potentials of Flipped Learning in Intercultural Education as a Transversal Resource in Adolescents. Religions 2020, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojo, F.J.; Aznar, I.; Romero, J.M.; Marín, J.A. Influencia del aula invertida en el rendimiento académico. Una revisión sistemática. Campus Virtuales 2019, 8, 9–18. Available online: https://bit.ly/2MP6Arz (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Parra-González, M.E.; López, J.; Segura-Robles, A.; Fuentes, A. Active and Emerging Methodologies for Ubiquitous Education: Potentials of Flipped Learning and Gamification. Sustainability 2020, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A. Uso de smartphones y redes sociales en alumnos/as de educación primaria. Prism. Soc. 2018, 1, 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, M.P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; McGraw Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2014; pp. 129–168. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, N. Diseños experimentales en educación. REP 2011, 32, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hinojo, F.J.; López, J.; Fuentes, A.; Trujillo, J.M.; Pozo, S. Academic Effects of the Use of Flipped Learning in Physical Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Fuentes, A.; López, J.A.; Pozo, S. Formative Transcendence of Flipped Learning in Mathematics Students of Secondary Education. Mathematics 2019, 7, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.J.; Romero, J.M.; López, J.; Alonso, S. Flipped learning approach as educational innovation in water literacy. Water 2020, 12, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, P.N.; Feng, S.T. Using a Tablet Computer Application to Advance High School Students’ Laboratory Learning Experiences: A Focus on Electrical Engineering Education. Sustainability 2019, 11, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, A.; Soyer, F. Effect of Physical Education and Play Applications on School Social Behaviors of Mild-Level Intellectually Disabled Children. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, T. Flipped Learning and Democratic Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, D.; Sáenz, M.; Santiago, R.; Chocarro, E. Diseño de un instrumento para evaluación diagnóstica de la competencia digital docente: Formación flipped classroom. DIM 2016, 1, 1–15. Available online: https://bit.ly/2BlOqby (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Santiago, R.; Bergmann, J. Aprender al Revés, 1st ed.; Paidós Educación: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; pp. 133–142. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).