The Effect of Layout and Colour Temperature on the Perception of Tourism Websites for Mobile Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. TAM Constructs

2.2. Colour Temperature

2.3. Layout of Information

2.4. Gaps in the Existing Literature

3. Method

3.1. Research Objective

- Is layout more associated with utilitarian or hedonic attributes?

- Is colour temperature more associated with utilitarian or hedonic attributes?

- Which of layout and colour temperature is more associated with intention to use?

- Do layout and colour temperature interact to influence any of the TAM constructs?

- Are the relationships between the design elements (layout and colour temperature) and the TAM constructs moderated by gender?

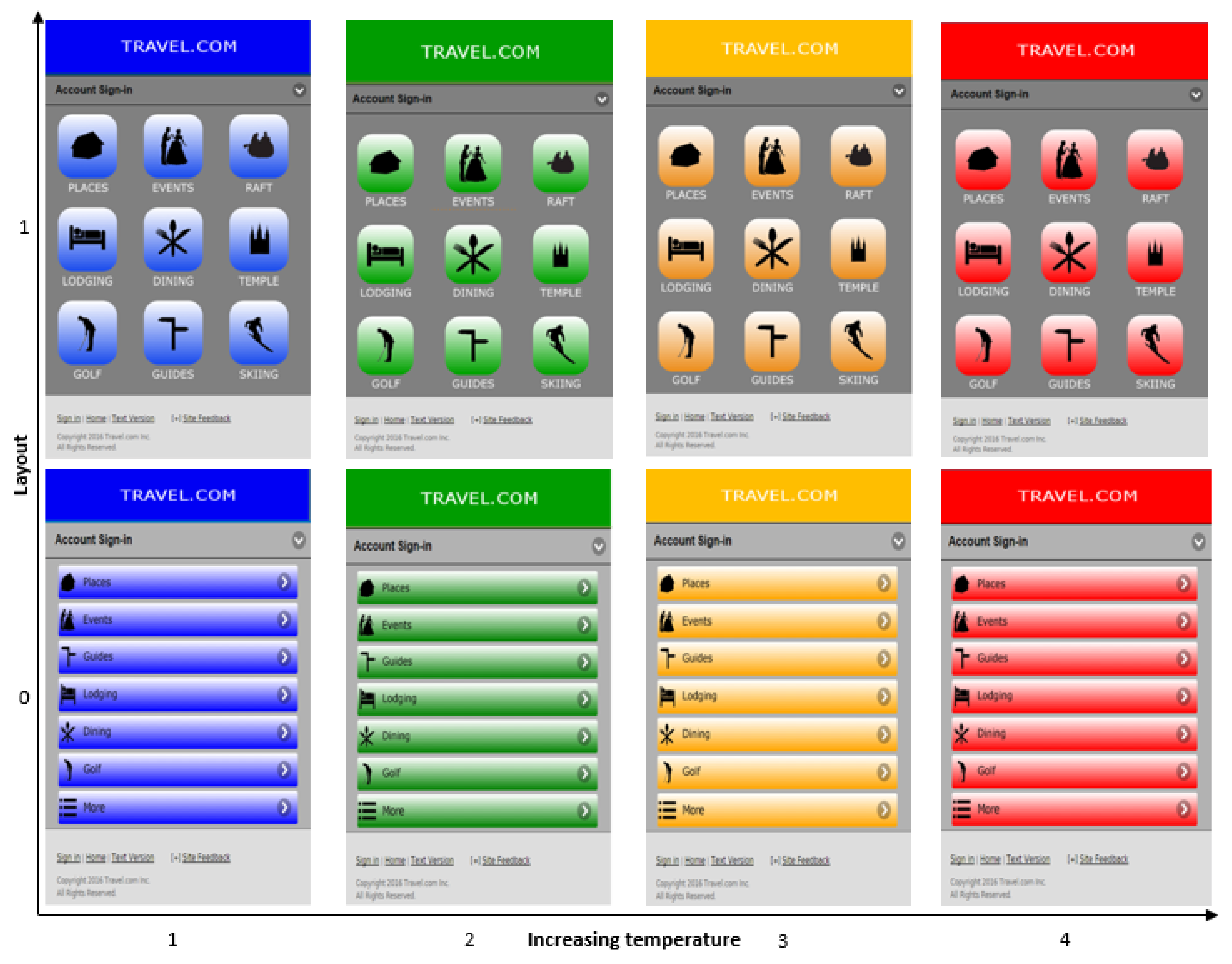

3.2. Rationale for Website Designs, Layouts and Colour Schemes

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Measurement Instruments

3.5. Participants

4. Result

4.1. Measurement Models

4.1.1. Indicator Reliability

4.1.2. Internal Consistency Reliability

4.1.3. Convergent Validity

4.1.4. Discriminant Validity

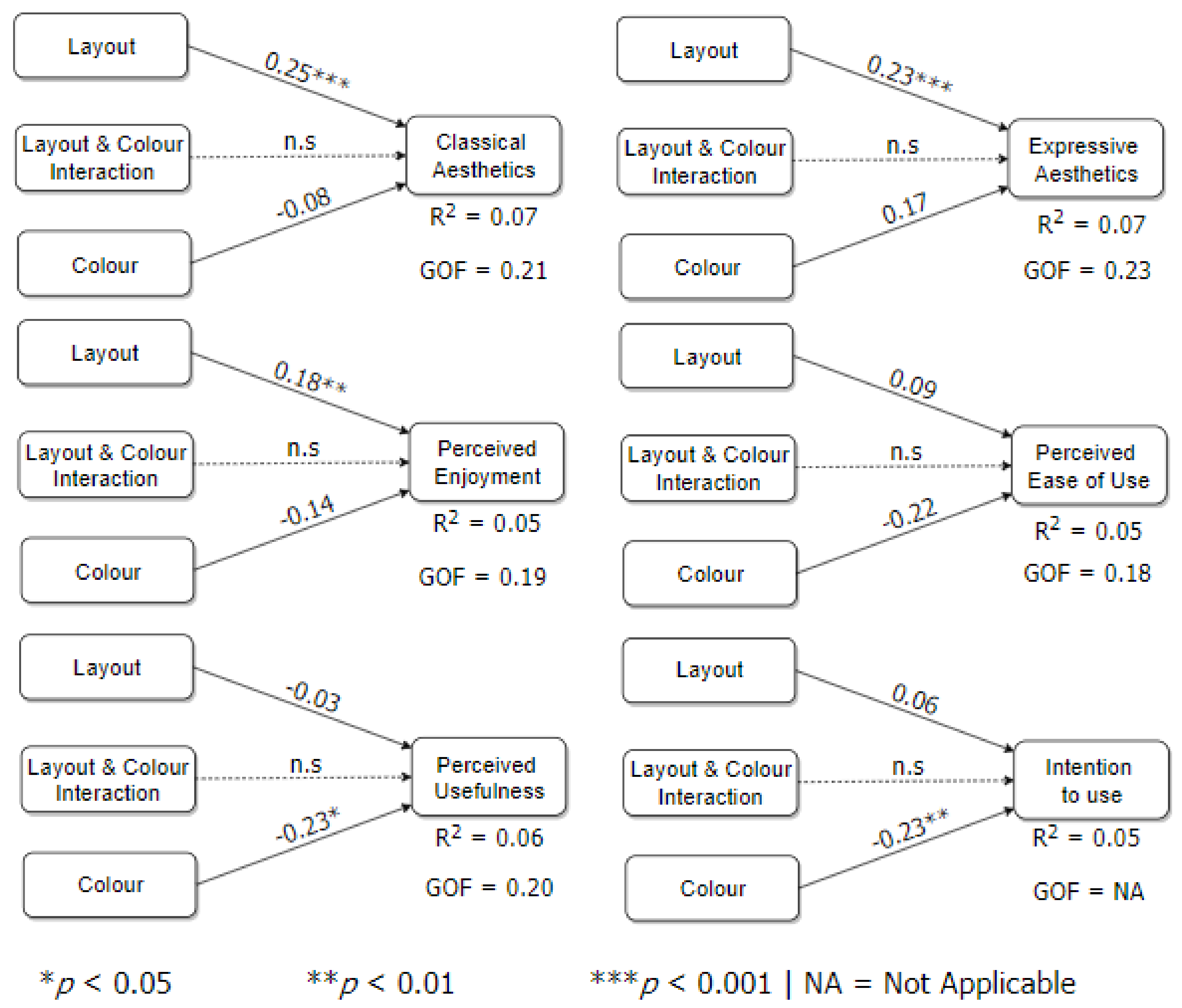

4.2. Structural Models

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Work

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, J. Mobile eCommerce Stats in 2018 and the Future Trends of mCommerce. Available online: https://www.outerboxdesign.com/web-design-articles/mobile-ecommerce-statistics (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- Fogg, B.J.; Soohoo, C.; Danielson, D.; Marable, L.; Stanford, J.; Tauber, E.R. How Do People Evaluate a Web Site ’ s Credibility ? Results from a Large Study; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lavie, T.; Tractinsky, N. Assessing dimensions of perceived visual aesthetics of web sites. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2004, 60, 269–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastin, L. The Basics of Philosophy. 2018. Available online: http://www.philosophybasics.com/branch_aesthetics.html (accessed on 23 September 2017).

- Wigelius, H.; Väätäjä, H. Dimensions of Context Affecting User Experience in Mobile Work. In Advances in Visual Computing; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 5727, pp. 604–617. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Heijden, H. User Acceptance of Hedonic Information Systems. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schaik, P.; Ling, J. The role of context in perceptions of the aesthetics of web pages over time. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2009, 67, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heijden, H. Factors influencing the usage of websites: The case of a generic portal in The Netherlands. Inf. Manag. 2003, 40, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyibo, K.; Adaji, I.; Orji, R.; Vassileva, J. What Drives the Perceived Credibility of Mobile Websites: Classical or Expressive? In In Proceedings of the International Conference of Human-Computer Interaction, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 576–594. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, L.P.; Ahmad, Z.A. Perceived Enjoyment and Malaysian Consumers’ Intention to Use a Single Platform E-Payment. SHS Web Conf. 2015, 18, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guohua, Z. Analysis of Graphic Design and Color Application in Tourism Advertising. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Social Science and Technology Education, Sanya, China, 11–12 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnardel, N.; Piolat, A.; Le Bigot, L. The impact of colour on Website appeal and users’ cognitive processes. Displays 2011, 32, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coursaris, C.K.; Swierenga, S.J.; Watrall, E. An empirical investigation of color temperature and gender effects on web aesthetics. J. Usability Stud. 2008, 3, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Soldat, A.S.; Sinclair, R.C.; Mark, M.M. Color as an Environmental Processing Cue: External Affective Cues Can Directly Affect Processing Strategy Without Affecting Mood. Soc. Cogn. 1997, 15, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratova, I.; Goldfarb, I. Color Your Website: Use of Colors on the Web. In Proceedings of the Advances in Visual Computing; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 4560, pp. 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kondratova, I.; Goldfarb, I. Cultural Interface Design: Global Colors Study. In Computer Vision; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 4277, pp. 926–934. [Google Scholar]

- Oyibo, K.; Ali, Y.S.; Vassileva, J. An Empirical Analysis of the Perception of Mobile Websites and the Influence of Culture. In In Proceedings of the Personalization in Persuasive Technology Workshop, Salzburg, Austia, 5 April 2016; pp. 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Oyibo, K.; Adaji, I.; Vassileva, J. The Effect of Age and Information Design on the Perception of Visual Aesthetics. In Proceedings of the 32nd International BCS Human Computer Interaction Conference, Belfast, UK, 4–6 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bart, Y.; Shankar, V.; Sultan, F.; Urban, G.L. Are the Drivers and Role of Online Trust the Same for All Web Sites and Consumers? A Large-Scale Exploratory Empirical Study. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-Y.; Lee, C.-L.; Fu, C.-S.; Wang, H.-C. How can online store layout design and atmosphere influence consumer shopping intention on a website? Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2013, 42, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyibo, K.; Hamada, M. A Framework for Instantiating Native Mobile Multimedia Learning Applications on Android Platform. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing & Multimedia—MoMM ’13, Association for Computing Machinery (ACM). Vienna, Austria, 2–4 December 2013; pp. 589–593. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk, M.M. Design, Layout and Review Factors that Influence Consumer Trust in Online Stores and Best Practices for Optimization; University of Oregon: Eugene, OR, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oyibo, K.; Orji, R.; Vassileva, J. The Influence of Personality on Mobile Web Credibility. In Proceedings of the Adjunct Publication of the 25th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization—UMAP ’17; Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), Bratislava, Slovakia, 9–12 July 2017; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Oyibo, K.; Adaji, I.; Vassileva, J. Mobile Web Design: The Effect of Education on the Influence of Classical and Expressive Aesthetics on Perceived Credibility. In Advances in Visual Computing; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester, M.D.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S.D. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, W.; Suri, S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods 2011, 44, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, P. Causal Relationships between Perceived Enjoyment and Perceived Ease of Use: An Alternative Approach. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2006, 7, 618–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, G. PLS Path Modeling with R. In Berkley: Trowchez Editions; Berkley University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–222. [Google Scholar]

- Oyibo, K.; Ali, Y.S.; Vassileva, J. Gender Difference in the Credibility Perception of Mobile Websites. In Proceedings of the 2016 conference on 3rd ACM Conference on Information-Centric Networking—ACM-ICN ’16, Association for Computing Machinery (ACM). Kyoto, Japan, 26–28 September 2016; pp. 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Oyibo, K.; Adaji, I.; Vassileva, J. The Influence of Internet Experience on the Judgment of Mobile Web Design. In Proceedings of the 32nd Human-Computer Interaction Conference, Belfast, UK, 2–6 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Definition of Construct |

|---|---|

| Classical Aesthetics | It entails the traditional notion of beauty, which is described by terms such as “well-organized,” “symmetrical,” “clean,” “clear,” etc. [3,9]. |

| Expressive Aesthetics | It entails the creativity and originality of the designer, including his/her ability to go beyond design conventions. It is described by terms such as “sophisticated,” “fascinating,” “creative,” etc. [3,9]. |

| Perceived Ease of use | The degree to which a user believes that using a website will be free of effort [10]. |

| Perceived Usefulness | The degree to which a user believes a website will help him/her perform his/her intended task [10]. |

| Perceived Enjoyment | The degree to which using a system is perceived to be enjoyable regardless of the actual performance of the system [11]. |

| Intention to Use | A measure of the users’ intention to use a website if deployed in a real-life context. |

| Construct | Example Items in Scale |

|---|---|

| Classical Aesthetics [7] | 1. The website is visual 2. The website is clean 3. The website is pleasant |

| Expressive Aesthetics [7] | 1. The website is creative 2. The website is fascinating 3. The website is sophisticated |

| Perceived Ease of Use [10] | 1. I would find the website easy to use 2. I would find the website to be flexible to interact with |

| Perceived Usefulness [10] | 1. Using website in my job would enable me to accomplish 2. Using website in my job would increase my productivity |

| Perceived Enjoyment [6] | 1. Using the website to do my job would be [Dull (1) … Exciting (7)] 2. Using the website to do my job would be [Pleasant (1) … Unpleasant (7)] |

| Intention to Use [29] | Assuming the website would be available on my job, I predict that I will use it. |

| Criterion | Breakdown |

|---|---|

| Gender | Male (52.3%); Female (47.4%); Undisclosed (0.3%) |

| Age | 18–24 (17.3%); 25–34 (44.6%); > 34 (38.1%) |

| Education | Technical/Trade School (18.9%); High School (19.2%); Bachelor’s degree (44.9%); Postgraduate Degree (14.9%); Others (2.1%) |

| Continent | North America (84.2%); Africa (4.0%); Asia (5.9%); Others (2.8%) |

| Construct | Layout | Colour | Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Aesthetics | 0.25*** | −0.08 | No |

| Expressive Aesthetics | 0.23*** | 0.17 | No |

| Perceived Enjoyment | 0.18** | −0.14 | No |

| Perceived Ease of Use | 0.09 | −0.22 | No |

| Perceived Usefulness | −0.03 | −0.23* | No |

| Intention to Use | 0.06 | −0.23** | No |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oyibo, K.; Vassileva, J. The Effect of Layout and Colour Temperature on the Perception of Tourism Websites for Mobile Devices. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4010008

Oyibo K, Vassileva J. The Effect of Layout and Colour Temperature on the Perception of Tourism Websites for Mobile Devices. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2020; 4(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleOyibo, Kiemute, and Julita Vassileva. 2020. "The Effect of Layout and Colour Temperature on the Perception of Tourism Websites for Mobile Devices" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 4, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4010008

APA StyleOyibo, K., & Vassileva, J. (2020). The Effect of Layout and Colour Temperature on the Perception of Tourism Websites for Mobile Devices. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 4(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4010008