1. Introduction

Human–AI interaction is increasingly used to support complex skill acquisition by providing timely, interpretable feedback while keeping the learner in control of decision-making. In second-language pronunciation training, this interaction is especially valuable because learners often need actionable cues about where their speech deviates from target pronunciations—feedback that traditional computer-assisted instruction and word-level ASR correctness checks frequently fail to provide. In this work, we use “human–AI interaction” to refer to an iterative feedback loop in which learners produce speech, inspect machine-generated phoneme-level indications of mismatch, and adjust their pronunciation in subsequent attempts. This definition is consistent with established design guidance and user-centered perspectives in Human–AI interaction research, which emphasize transparent feedback, iterative refinement, and maintaining user agency in decision-making [

1,

2].

Mobile-assisted language learning (MALL) applications have become increasingly popular due to their accessibility, scalability, and integration with modern digital ecosystems. However, analyses of leading platforms (e.g., Duolingo, HelloChinese, Babbel) reveal a critical technological gap: pronunciation assessment in these systems relies predominantly on automated speech recognition (ASR). As demonstrated in recent research, ASR-based assessment is primarily designed to determine what a learner said rather than how it was pronounced, providing low-granularity evaluations that fail to detect phonetic deviations such as consonant substitutions, vowel omissions, and prosodic errors [

3]. Consequently, these systems often offer only word-level correctness judgments without detailed diagnostic feedback that could guide learners toward meaningful improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Architecture

The system follows a client–server architecture. The client is a WeChat Mini Program v8.0.60, selected due to its cross-platform runtime and native access to device audio APIs. It captures speech using the built-in recording interface, packages the audio together with exercise metadata, and transmits it to the server via a persistent WebSocket channel to support low-latency interaction.

The server, implemented in Python 3.7.3, consists of three functional layers: a communication layer that manages WebSocket sessions and message serialization; a speech-processing layer that performs silence trimming, phoneme recognition using a Wav2Vec-based phoneme model, and normalization of the resulting symbolic phoneme sequence; and an analysis layer that aligns the learner’s and reference phoneme sequences using the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm. After alignment, a lightweight post-processing step labels each aligned position as a match, substitution, insertion, or deletion and produces a structured representation of deviations for visualization.

The data flow is as follows: the client records speech, sends audio to the server, the server extracts phonemes and retrieves the reference sequence, alignment and error analysis are performed, the server returns a compact JSON structure describing the phoneme-level comparison for visualization on the client. This division keeps the client lightweight while centralizing all computationally intensive processing on the server.

2.2. Speech Assessment Algorithm

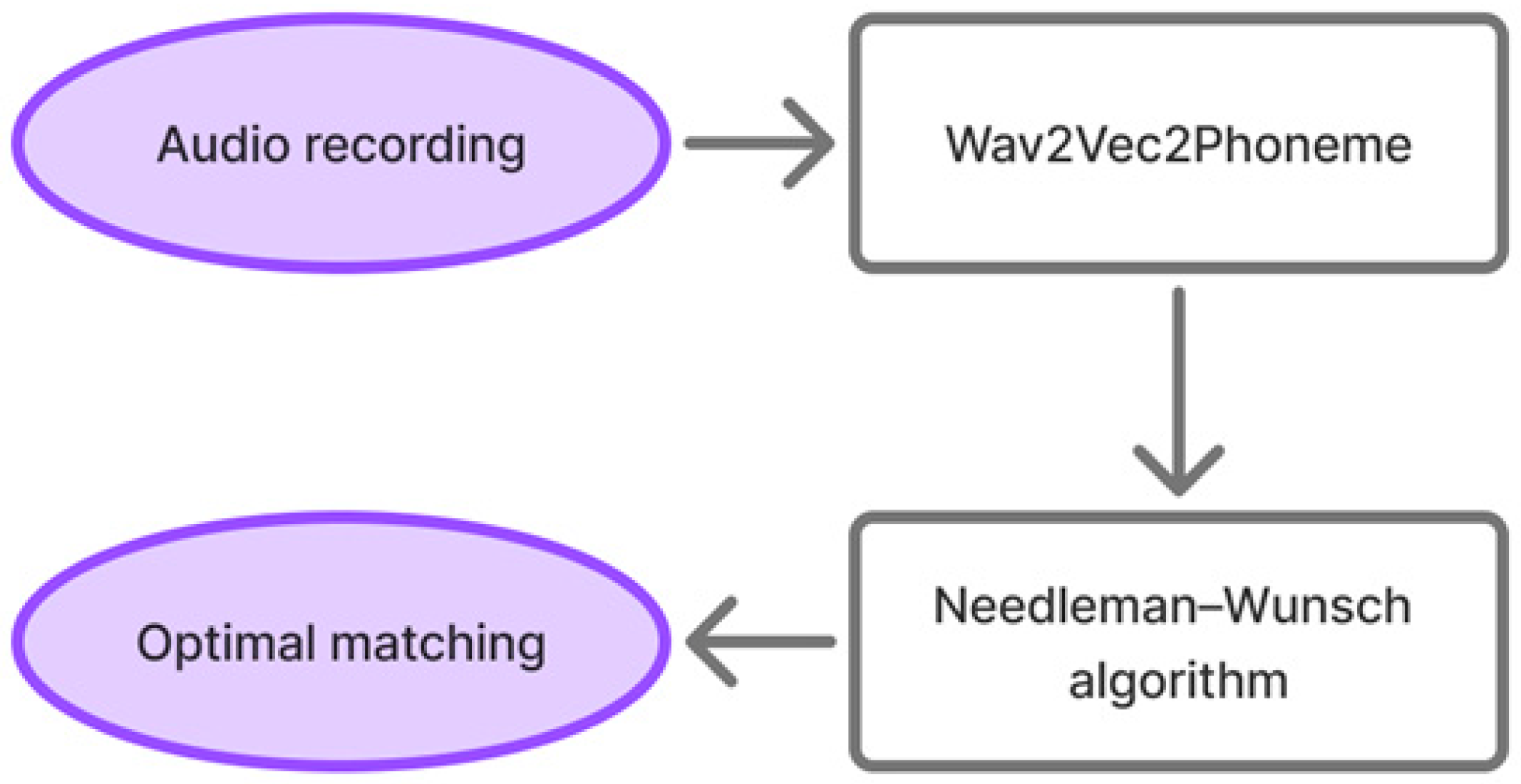

The assessment pipeline consists of two main stages, as shown in

Figure 1.

2.2.1. Phoneme Recognition

The first stage involves converting raw audio into a sequence of phonemes. We employ the Wav2Vec2Phoneme model [

8], a method for zero-shot cross-lingual phoneme recognition based on the multilingual wav2vec 2.0 XLSR-53 architecture pre-trained on speech from 53 languages. The model generates a sequence of phonetic symbols in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), supporting a language-general phoneme-level representation that does not require hand-labeled Russian phoneme datasets for initialization. However, recognition accuracy and downstream error localization may vary across languages and learner populations, so cross-language deployment should be validated empirically.

The Wav2Vec2Phoneme (multilingual) model derives from the approach described by Xu, Baevski & Auli [

9], which achieves strong zero-shot cross-lingual phoneme recognition performance. Although their original work does not provide explicit phoneme-level accuracy metrics for Russian, their results demonstrate strong zero-shot transfer across many languages with similar phonological inventories. Recent multilingual benchmarks further confirm that wav2vec-based phoneme recognizers achieve competitive performance on Slavic languages in zero-shot settings.

Several external studies provide reliable estimates of phoneme-level performance for wav2vec-based models applied to Russian. Xu, Baevski and Auli demonstrated that the multilingual Wav2Vec 2.0 (XLSR-53) architecture achieves strong zero-shot cross-lingual phoneme recognition across a wide range of languages, including Russian, due to its robust multilingual pre-training, even though explicit Russian phoneme supervision is not used [

8]. Complementary evidence is provided by the CommonPhone corpus introduced by Klumpp, where a Wav2Vec2 model fine-tuned on multilingual phoneme-labeled data achieved a phoneme error rate (PER) of 18.1% on the full phoneme inventory with only minor differences between languages, Russian among them [

10]. While this result motivates our choice of a multilingual phoneme front-end, performance in our deployment (learner speech and task-specific prompts) remains an empirical question. Additional multilingual evaluations further confirm that self-supervised wav2vec-based models yield competitive PER values for Slavic languages under both low-resource and zero-shot conditions [

11,

12]. Taken together, these external results indicate that modern wav2vec-derived architectures provide sufficiently high phoneme-level accuracy to support downstream alignment and pronunciation assessment in Russian.

Overall, the zero-shot Wav2Vec2Phoneme approach offers a reliable foundation for downstream alignment and pronunciation assessment while avoiding the need for large-scale Russian phoneme-labeled datasets.

Although the present study focuses on Russian, the underlying Wav2Vec2Phoneme model is multilingual, and the downstream alignment procedure is not tied to a specific language. However, extending the system to additional languages is not “plug-and-play”: it requires language-specific resources, including an appropriate phoneme inventory (and mapping conventions), task prompts, and native-speaker reference recordings. In addition, typologically distant languages may exhibit different phonotactic patterns and error distributions, which can affect recognition accuracy and may motivate adjustment of preprocessing and/or alignment settings. Therefore, multilingual transfer is a feasible direction but remains an empirical question for future work.

2.2.2. Phoneme Sequence Alignment

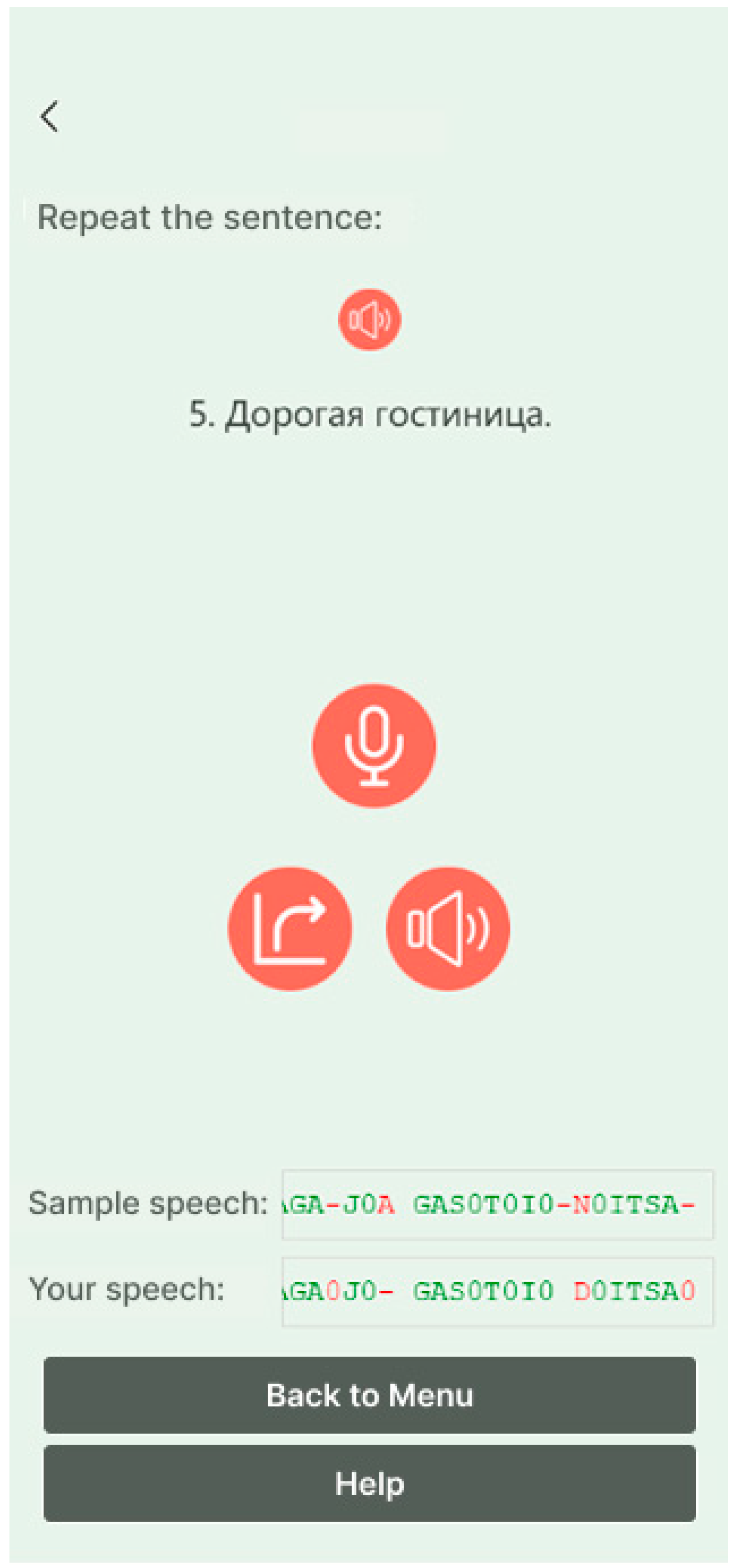

The user’s phoneme sequence is aligned with the native speaker reference sequence using the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm. This dynamic programming method computes an optimal global alignment between two sequences. The alignment is used to generate localized, interpretable feedback: the system does not present an overall pronunciation score; instead, it displays the reference and user phoneme strings with phoneme-level highlighting, where aligned matches are shown in green and mismatches are shown in red (

Figure 2).

The interface (

Figure 2) displays the reference audio (“Sample speech”) and the learner recording (“Your speech”), alongside IPA-based phoneme transcriptions. Phonemes aligned as matches are highlighted in green, while mismatches inferred from sequence alignment are highlighted in red. The system does not provide an aggregate pronunciation score; feedback is localized to phoneme positions.

We use the following Needleman–Wunsch scoring parameters:

Match: +1 (for a correct phoneme).

Mismatch: −1 (for a substituted phoneme).

Gap Penalty: −1 (for an inserted or deleted phoneme).

We use a symmetric scoring scheme as a transparent baseline for learner utterances, where the primary goal is stable error localization rather than optimizing an aggregate score. Treating substitutions and insertions/deletions with equal penalty yields consistent alignments under an easily reproducible setting. The parameters were selected a priori (i.e., not tuned on an evaluation set) to avoid overfitting to a particular prompt list or learner group.

The output is two aligned sequences of equal length, where gaps (“” in the alignment output; optionally rendered as blank space in the UI) indicate insertions or deletions. For example, the alignment between the reference sequence (R) and the user sequence (U) may be:

R: GAS0T0I0-N0ITSA-.

U: GAS0T0I0 D0ITSA0.

Here, the blank space in the user sequence indicates an alignment gap (i.e., “no produced phoneme” at that position); the alignment algorithm represents such gaps explicitly, while the user-facing transcription renders them as whitespace for readability.

From each aligned pair , we label events as follows: a correct phoneme if (highlighted green), a deletion if , an insertion if , and a substitution otherwise. In all non-match cases, the corresponding non-gap phoneme(s) in the rendered reference/user strings are highlighted red, yielding the binary red/green transcription shown to the learner. Optionally, for analysis and interpretation, substitutions can be grouped by broad phonetic classes, but this grouping does not affect the alignment.

2.3. Mobile Application Implementation and Data Handling

The pronunciation training application is implemented as a WeChat Mini Program, with client-side interface and logic developed using WXML (markup), WXSS (styling), and JavaScript (interaction logic). Speech processing is performed server-side: the backend receives audio from the client, runs phoneme recognition, aligns the user and reference phoneme sequences, and returns data required to render phoneme-level feedback.

The Mini Program records speech using the built-in recorder manager and stores the recording locally as a temporary WAV file. When the user requests analysis, the client reads the audio file and transmits it as a base64-encoded payload over WebSocket.

The client maintains a persistent WebSocket connection to support lightweight request/response interaction. At the start of a task, the client first sends a task identifier. The server uses this identifier to retrieve the corresponding reference recording and returns the reference WAV bytes to the client (for playback). The client then sends the learner’s recorded audio (base64) for analysis. The server responds with a structured JSON payload containing the aligned reference and user phoneme sequences, which the client uses to render red/green highlighting.

The backend is implemented in Python using an asynchronous WebSocket server (asyncio). Phoneme recognition is performed using a Wav2Vec2-based speech recognition model loaded via the HuggingSound interface. For each request, the server transcribes both the reference recording and the learner recording into phoneme sequences, then applies the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm (

Section 2.2.2) to compute an optimal global alignment. The server returns the aligned sequences (including gap markers) to the client for visualization.

The Mini Program renders the aligned sequences as a “reference transcription” and a “user transcription.” For each aligned position, the client applies a deterministic highlighting rule: if the characters match at that aligned index, the symbol is highlighted green; otherwise, it is highlighted red. Gap markers produced by alignment are treated as insertion/deletion indicators and can be displayed as explicit placeholders or suppressed in the UI depending on layout constraints.

The client includes basic handling for dropped connections, timeouts, and invalid server responses. If analysis fails, the interface prompts the user to retry rather than displaying potentially misleading feedback. These choices support safe use under variable network conditions typical for mobile settings.

In the current implementation, recordings are transmitted for processing and are not intended to be retained permanently on the client. Server-side retention (if enabled for debugging or evaluation) can be limited and disabled in deployment configurations to minimize storage of sensitive speech data.

3. Results

3.1. Algorithm Implementation

The server-side algorithm was successfully implemented using the HuggingSound library for phoneme recognition and NumPy for the Needleman-Wunsch alignment. The WebSocket server reliably handles client requests, sending either reference audio or analysis results.

The processing pipeline is largely reusable across languages, but the overall system is not fully language-independent. Deploying it in a new language requires language-specific resources (phoneme inventory and symbol conventions, task texts, and native-speaker reference recordings) and may require adjusting preprocessing and/or alignment settings to reflect the target language’s phonotactics and typical learner error patterns. Accordingly, cross-language deployment is a supported design goal, but it is not validated in the present study beyond Russian.

3.2. Application Interface

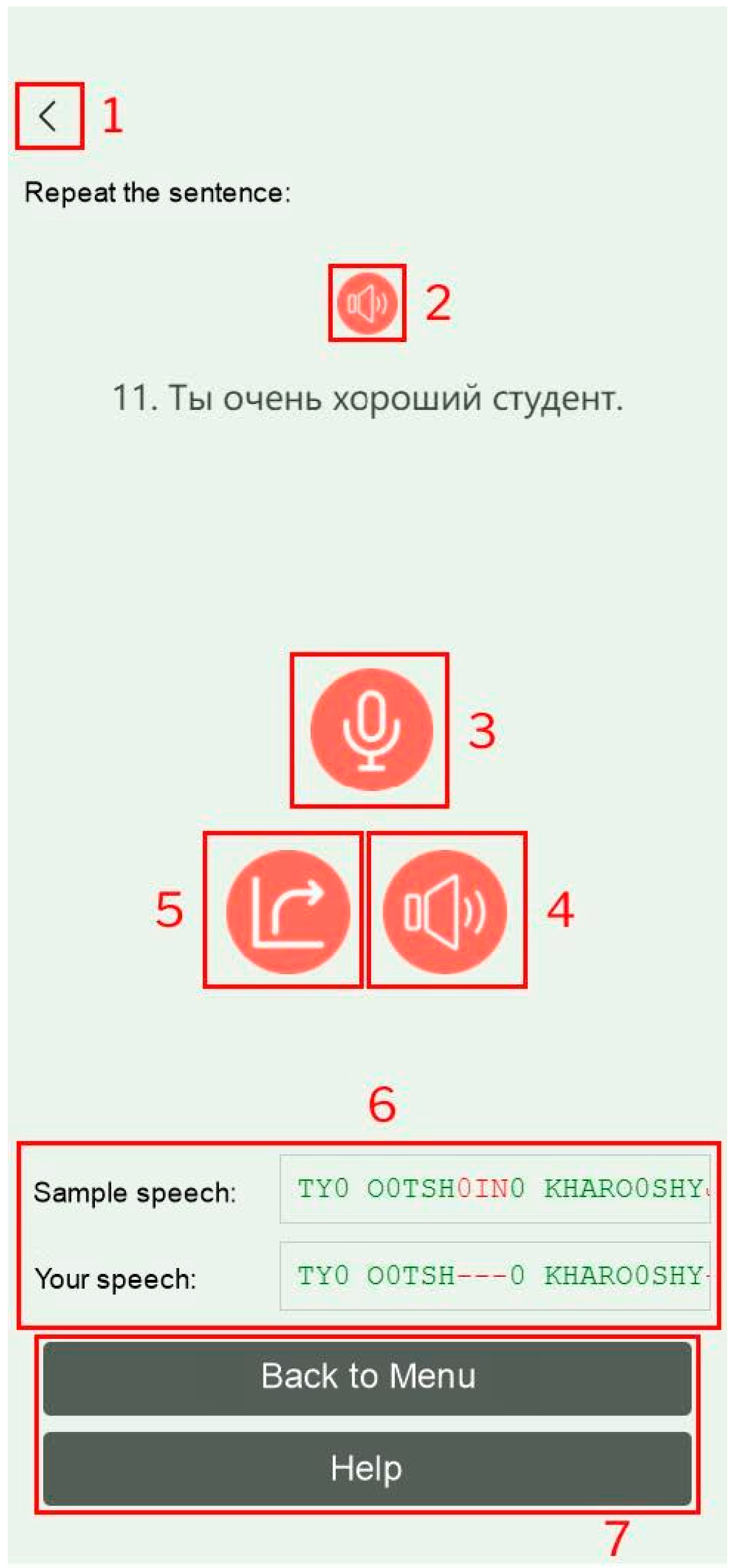

The mobile application provides a clean, intuitive user interface (

Figure 3).

Where the numbered items in

Figure 3 indicate:

The button for returning to the previous page;

The button for playing the native speaker’s audio recording corresponding to the task text shown in the line below;

The button for recording the user’s voice;

The button for playing back the user’s voice;

The button for sending the recording to the server for pronunciation assessment;

The block for displaying the phonemic representations of the native speaker’s and the user’s recordings;

The standard buttons for returning to the menu and navigating to the instruction page.

The color scheme was designed for prolonged use, and all interactive elements are clearly distinguishable. The core functionality—recording, playback, and submission—functions seamlessly.

Because IPA phoneme sequences may exceed the available screen width, block 6 displays them in a horizontally scrollable, monospaced text area. This layout allows users to view the complete sequences and compare the native-speaker and learner transcriptions character by character.

3.3. Comparative Analysis

A feature-level comparison was performed against three widely used language-learning applications (

Table 1). The comparison focuses on observable differences in the granularity and interpretability of pronunciation feedback rather than comparative accuracy.

Table 1 highlights that Duolingo, HelloChinese, and Babbel typically provide pronunciation feedback at the word or phrase level, often indicating whether an utterance is accepted by the ASR component, but without explicitly localizing errors at the phoneme level or providing phoneme-segment diagnostics. HelloChinese additionally presents Pinyin with tone markers for reference content, which can support learner self-monitoring in Chinese, but it does not provide an IPA-based aligned comparison of learner and reference pronunciations.

In contrast, the proposed application is designed to provide phoneme-level feedback by converting both reference and learner speech into phoneme sequences and aligning them using Needleman–Wunsch (

Section 2.2.2). The learner-facing interface visualizes this alignment using deterministic red/green highlighting, enabling users to identify where deviations occur (e.g., mismatched segments and gaps corresponding to insertion/deletion events). This comparison is intended to characterize feedback granularity and interpretability; controlled evaluation is required to compare recognition accuracy or learning effectiveness across systems.

4. Discussion

The implementation demonstrates the feasibility of combining modern speech-to-phoneme models with robust sequence alignment algorithms for pronunciation assessment. The primary advantage of this method is its ability to move beyond binary “correct/incorrect” feedback and provide learners with specific, actionable insights. By visualizing the alignment, a learner can see precisely which sound was mispronounced, omitted, or added.

The choice of WeChat Mini Programs as a platform proved advantageous, offering a balance between native functionality and cross-platform development efficiency. However, a limitation is the application’s dependence on a stable internet connection for server communication.

Although the current version of the system has been validated only for Russian, this limitation mainly reflects the availability of curated prompts and pedagogical materials. The alignment procedure itself is not tied to a specific language, and the overall pipeline is reusable in principle; however, adaptation to additional languages requires language-specific resources (phoneme inventories and symbol conventions, task prompts, and native-speaker reference recordings). Moreover, recognition accuracy and typical learner error patterns may differ across languages—especially for typologically distant languages—which can affect downstream error localization and may motivate adjustment of preprocessing and/or alignment settings. For these reasons, multilingual extension is a promising direction but should be treated as future work requiring dedicated evaluation.

At the current stage, the system does not explicitly model dialectal variation or alternative acceptable pronunciations, which may lead to false substitution flags for legitimate variants.

First, phoneme-level feedback inherits errors from the phoneme recognizer: misrecognized segments can propagate into the alignment and lead to incorrect red/green highlighting, particularly for short utterances, noisy recordings, and non-native pronunciations that fall outside the model’s training distribution. Second, the current system relies on fixed reference prompts and does not explicitly model acceptable pronunciation variants (e.g., dialectal variation or alternative realizations), which may cause the system to flag legitimate variants as errors. Third, the current feedback is primarily segmental (phoneme-level) and does not assess suprasegmental aspects such as stress, rhythm, and intonation, which can be critical for intelligibility and perceived accent. Finally, the interface does not yet communicate model uncertainty; without confidence-aware feedback, low-confidence diagnoses may be presented with the same visual salience as high-confidence ones. These limitations motivate future work on calibration using learner data, multi-variant references, prosody-aware feedback, and confidence-conditioned highlighting policies.

The current system primarily focuses on segmental pronunciation accuracy. Future work will focus on empirical validation, confidence-aware and prosody-sensitive feedback, and usability-driven refinement of the interface (including progress tracking).

An alternative approach based on Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC) and Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) could be implemented for future research. This method involves converting audio into MFCC feature vectors and using DTW to align these numerical time series [

13,

14,

15,

16]. While DTW handles temporal variations effectively, initial experiments showed that the raw amplitude subtraction and DTW alignment do not always produce satisfactory results, as they do not account for the linguistic content of the sounds. The phoneme-based approach in current research was selected for its superior interpretability and direct focus on phonetic accuracy.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents development of a mobile application for assessing and improving pronunciation in Russian as a foreign language. The core innovation is an adaptive algorithm that provides phoneme-level feedback by aligning user and reference phonetic sequences using the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm. This approach provides phoneme-level, alignment-based feedback with localized red/green highlighting, contrasting with the more common word-level pronunciation checks in many commercial applications.

Future work will prioritize empirical validation and learner-facing utility. Specifically, we plan to:

Evaluate phoneme recognition performance on representative Russian learner speech, reporting error rates and common confusions, and quantify how recognition errors propagate into alignment-based highlighting.

Validate alignment-based error localization (substitution/insertion/deletion) against a small expert-annotated reference set to estimate reliability of the red/green feedback.

Measure end-to-end latency of the WebSocket pipeline under typical mobile network conditions to substantiate real-time usability claims.

Conduct user studies (e.g., SUS, perceived feedback clarity/usefulness, and qualitative interviews) to assess usability and to inform interface refinement, including progress tracking features.

Extend the system toward confidence-aware feedback, multi-variant reference pronunciations (to reduce false error flags for acceptable variants), and prosody-sensitive analysis (stress/intonation), which are not assessed in the current version.

Complete and evaluate the MFCC/DTW baseline as a complementary comparison method, focusing on interpretability and alignment robustness rather than claiming accuracy advantages without controlled experiments.

This research contributes to computer-assisted language learning (CALL) by demonstrating a pronunciation-training application that provides interpretable, phoneme-level feedback via phoneme recognition and sequence alignment. While the core alignment-based feedback mechanism is broadly reusable, extension to additional languages requires language-specific resources (phoneme inventory and conventions, prompts, and reference recordings) and should be validated empirically for each target language. Future work will therefore prioritize multilingual evaluation (e.g., Chinese, English, Spanish) alongside interface improvements and broader user studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.; Methodology, A.D.; Software, G.V.; Validation, A.D.; Formal analysis, A.D.; Resources, D.C.; Data curation, G.V.; Writing—original draft, G.V.; Writing—review & editing, A.D.; Visualization, G.V.; Supervision, A.D. and D.C.; Project administration, A.D.; Funding acquisition, D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 12350410359.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Amershi, S.; Weld, D.; Vorvoreanu, M.; Fourney, A.; Nushi, B.; Collisson, P.; Suh, J.; Iqbal, S.; Bennett, P.N.; Inkpen, K.; et al. Guidelines for Human-AI Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T.; Sun, Z.; Fu, S.; Lv, Y. Human–AI Interaction Research Agenda: A User-Centered Perspective. Data Inf. Manag. 2024, 8, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Tang, Z.; Wang, D.; Zheng, T.F. ASR-Free Pronunciation Assessment. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2020, Shanghai, China, 25–29 October 2020; pp. 3047–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, S.M.; Young, S.J. Phone-level pronunciation scoring and assessment for interactive language learning. Speech Commun. 2000, 30, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.-C.; Fang, H.; Luo, X.; Xu, X.-S. Gradformer: A Framework for Multi-Aspect Multi-Granularity Pronunciation Assessment. IEEE ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2024, 32, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Fan, Z.; Svendsen, T.; Salvi, G. A Framework for Phoneme-Level Pronunciation Assessment Using CTC. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2024, Kos, Greece, 1–5 September 2024; pp. 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Nickolai, D.; Jones, L. Traditional Versus ASR-Based Pronunciation Instruction. CALICO J. 2020, 37, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strik, H.; Truong, K.; de Wet, F.; Cucchiarini, C. Comparing classifiers for pronunciation error detection. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2007, Antwerp, Belgium, 27–31 August 2007; pp. 1837–1840. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Baevski, A.; Auli, M. Simple and effective zero-shot cross-lingual phoneme recognition. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.11680. [Google Scholar]

- Klumpp, P. Common Phone: A Multilingual Dataset for Robust Acoustic Modelling. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2022), Marseille, France, 20–25 June 2022; pp. 763–768. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Low-Resource Speech Recognition for Thousands of Languages. Ph.D. Thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S.A.; Ali, M.; Stuker, S.; Waibel, A. Multilingual Self-Supervised Features for ASR and Quality Estimation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, V. MFCC and its applications in speaker recognition. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 1, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Jaafar, J.; Ahmad, W.F.W.; Bansal, A. Feature extraction using MFCC. Signal Image Process. Int. J. SIPIJ 2013, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittichaichareon, C.; Suksri, S.; Yingthawornsuk, T. Speech Recognition using MFCC. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Graphics, Simulation and Modeling, Pattaya, Thailand, 28–29 July 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Muda, L.; Begam, M.; Elamvazuthi, I. Voice Recognition Algorithms using Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficient (MFCC) and Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) Techniques. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1003.4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |