1. Introduction

“Data is the new gold”, Neelie Kroes, former Vice President of the European Commission and head of the Digital Agenda, titled her conference on open data strategy held in Brussels, highlighting the importance of this data in supporting a new model of digital economy [

1].

This statement was based on various studies. The first of these was Vickery (2011) [

2], “Open data, a driver for innovation, growth, and transparent governance”, which quantifies the value of open data at

$40 billion per year directly, increasing to

$140 billion per year if the indirect impact is also considered. The second, a report entitled “Creating value throw open data” [

3], estimates the value creation by open data at more than 1% of GDP. Finally, the report entitled “The impact of open data: opportunities for creation in Europe” [

4] indicates, in its conservative forecast, that the turnover of open data in the EU 27+ environment by 2025 would be between 199 and 344.2 billion, generating between 1.12 and 1.97 million jobs.

Therefore, it is not surprising that the interest in open data, a central element of government policies or open government [

5], for its ability to generate value, favors the solution of various public problems [

6,

7] and the development of smart cities [

8,

9].

In today’s digital society [

10], public administrations are the organizations that produce and manage the greatest amount of data. They offer open data without technical or legal restrictions and without requirements for use or permissions [

11] but with certain characteristics that make it valuable for free reuse [

12].

It is worth noting that although many countries have robust data protection legislations in place to preserve individual privacy and respect intellectual property, this does not necessarily conflict with open data initiatives. As mentioned in the first of the eight principles of open data [

13], called “complete”, all public data that is available and not subject to valid limitations should be made available, thus excluding data that could compromise privacy or security or data subject to legal or commercial restrictions.

For this reason, it is firmly believed that the open data movement is unstoppable. These open data are easily found through online platforms [

14] called open data portals.

Thus, given that open data contributes to innovation, it is logical that academic interest has increased [

15], despite the fact that its understanding in certain aspects is still scarce [

16]. This aspect, together with the undeniable interest in housing for citizens, businesses, and public administrations, has guided this work’s one main research question: What is the supply of open data in the housing category being disseminated by Spanish autonomous communities?

Two additional supplementary questions have been added. The first is motivated by the vague definition of housing content contained in the technical standard for interoperability, which invites a typological classification of the results found, differentiated according to their nature: subsidies and grants, prices (rental or sale/purchase), building data, mortgages, statistics, etc. Thus, the question to be answered is: Is there a uniform interpretation by Spanish autonomous communities regarding the content of information to be disclosed?

The second is in line with the obligation contained in Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and reuse of public sector information (amending Directive 2013/37/EU of 26 June 2013) [

17,

18], which mentions that public sector information must be provided in machine-readable open formats. This aspect raises the following research question: Are the formats used really of high quality? To this end, the formats in which the information is being disseminated have been reviewed (considering both their breadth and their reusability), which, incidentally, allows for the creation of an autonomous community ranking that equally values the number of datasets provided and the formats offered.

To achieve these three tasks, this research has been divided into five sections, with this introduction being the first of them. The second section then deals with the methodology and the justification of the object and approach of the study; the third section shows the main results obtained, which are analyzed and discussed in the fourth section, together with the main conclusions reached and the perspective. The paper concludes with the bibliographical references used in the preparation of the study.

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

Before reviewing academic studies, it is interesting to examine how open data initiatives are organized in Spain. Spain is a leader in open data portals with 279 operational initiatives, although not all of them are identified or classified as efficient initiatives due to the difficulty in terms of professional use [

19]. In this country, information is categorized according to the technical standard for interoperability [

20], which proposes a classification of the data provided in 22 categories (see

Figure 1).

The technical standard includes a proposal for a common taxonomy made up of the 22 categories mentioned above, indicating, succinctly, the content of each category (for example, it states that “Housing” should include information on the real estate market and housing construction).

There is no doubt that open data related to housing is of unquestionable interest to various actors (urban planners, construction companies, researchers, citizens, or governments), as it allows them to obtain different information such as prices or valuations (rents, purchases), volumes of supply and demand, number of dwellings (free, social or subsidized), and characteristics of the properties (surface area, number of rooms, age, etc.) that will favor informed decision making. Likewise, open housing data is a valuable resource for anticipating price trends; identifying geographic areas with potential growth or in the field of marketing (adapting products to the needs of consumers, creating content, carrying out geolocalized or better-segmented campaigns, useful for optimizing distribution channels, analyzing the competition, etc.); and finally, for creating public policies to promote affordable housing for vulnerable sectors such as young people and low-income families, among others.

Various initiatives featured on the datos.gob.es portal show how to identify and validate key data for the economic and commercial development of the real estate sector. Portals such as “Housing in data” from Barcelona City Council and the data visualization portal from Madrid City Council offer open, up-to-date, high-quality datasets such as consumer and housing price indices, land registry data, information for builders and companies for housing development, and data on energy demand in buildings [

21]. Likewise, private platforms such as Idealista and Fotocasa, together with companies specializing in data reuse such as La Gistería, Inspide, and Sociedad de Tasación, integrate cadastral, registry, and statistical data to generate interactive maps and automated valuations [

22]. These examples demonstrate that essential data—prices, volumes, building stock attributes, mortgages, and energy information—can be obtained through open portals that guarantee accessibility (csv, xml, json, and jscon formats), interoperability, and open licenses, facilitating their use in market analysis, commercial segmentation, and public policy formulation. All of this improves the functioning of the housing market and, therefore, greater efficiency, generating value.

Housing has become a constant demand worldwide, and as part of government openness, portals have been promoted with the aim of providing information that encourages decision making and joint interinstitutional collaboration [

23]. In Spain, housing is a sector of great relevance due to its contribution to GDP, and although the effects of recent interest rate increases are being felt [

24], housing sales and purchases have been at levels not seen since the real estate boom of the early 20th century in 2021 [

25].

Consequently, one would expect a wealth of research on open data related to housing in Spain. However, a consultation of a bibliographic database shows that this is far from the case. The database chosen was Scopus because it is considered suitable for demonstrating this aspect, both in terms of quantity and quality of articles: choosing WoS would have selected articles of generally higher quality but would have returned fewer results, while relying on Google Scholar would have reversed the parameters (a greater number of publications, but not all of a scientific/academic nature).

After justifying the choice of database, the search performed is shown below: open data OR open data AND Spain OR Spain, which located 112 works, a figure considered insufficient for a topic as crosscutting as open data.

The narrative review of the aforementioned articles shows that many of them focused their efforts on analyzing a specific topic such as health [

26,

27,

28], forestry data [

29,

30], education [

31], oceanography [

32], research [

33,

34], legal information [

35], libraries [

36], archaeology [

37], urban planning [

38], energy consumption [

39], attention to information science [

40], or transparency [

41,

42].

Only one of those studies, by Barrientos Matute and Ruvalcaba-Gómez, dealt with housing and concluded that non-governmental portals offer information of greater value than governmental ones. However, curiously, it did not refer to Spain but to Guadalajara in Mexico [

23].

After highlighting the lack of open data studies related to the housing sector in Spain, a brief review of the literature was conducted, analyzing a series of studies that present different approaches to studying open data in this country. Given that most of them aimed to assess whether initiatives are well or poorly designed by issuing a verdict on the matter, this paper outlines how they were approached, allowing for a comparison of the results with those of this study in the discussion section.

One of the pioneering studies is that of Garriga Portolá (2013) [

43], who begins by pointing out that, at the time of publication of the study, Spain was the only country in the European Union with more than one million inhabitants that did not have a law regulating the fundamental right of access to public information. The author notes that, despite this, Spain remains a benchmark in data openness and has made significant progress, although there are still notable gaps.

He then refers to a relevant group of researchers, led by Alberto Abella, who are engaged in analyzing open data in that country, conducting a series of periodic studies entitled “The reuse of open data in Spain”, whose conclusions are based on sample analyses.

The first of these [

44] points out that open data is an opportunity for Spain in three ways: increasing trust in public management, improving efficiency through easier use of public resources, and creating computer applications that take advantage of this data and generate economic value. However, over the years, there has been a noticeable shift in the researchers’ opinions, with a more critical tone. In the latest study [

45], it is noted that the increase in information provided is mostly statistical rather than primary.

Similarly, reference should be made to the research by Curto-Rodríguez, all of which is autonomous community in scope. The author incorporates the role of open data in generating value into his main line of research, which analyzes the role of open data in promoting transparency. The multidimensional study of the portals [

46] assesses the existence of information, existing computer applications, the possibilities for interaction with the portal, and its functionalities, highlighting the different performances of each autonomous community in each of the dimensions analyzed. Other works carried out by other authors focus on analyzing the population or demographic data provided [

47] or the role of accounting information in open data for accountability [

48].

After conducting a brief review of the literature, which revealed an interesting knowledge gap, this research focused on open data relating to housing in Spain, a largely decentralized country [

49] that is undoubtedly among the most decentralized in Western Europe [

50]. In Spain, the Spanish public sector is divided into three levels: the state, autonomous communities (comprising 17 autonomous communities, see

Figure 2), and local governments (comprising 50 provinces and 8112 municipalities), with a relationship among these governments based on competencies rather than hierarchy [

51]. The framework chosen was that of the autonomous communities, which have a great deal of autonomy and important handling of competencies, managing a high volume of public resources [

52].

4. Results

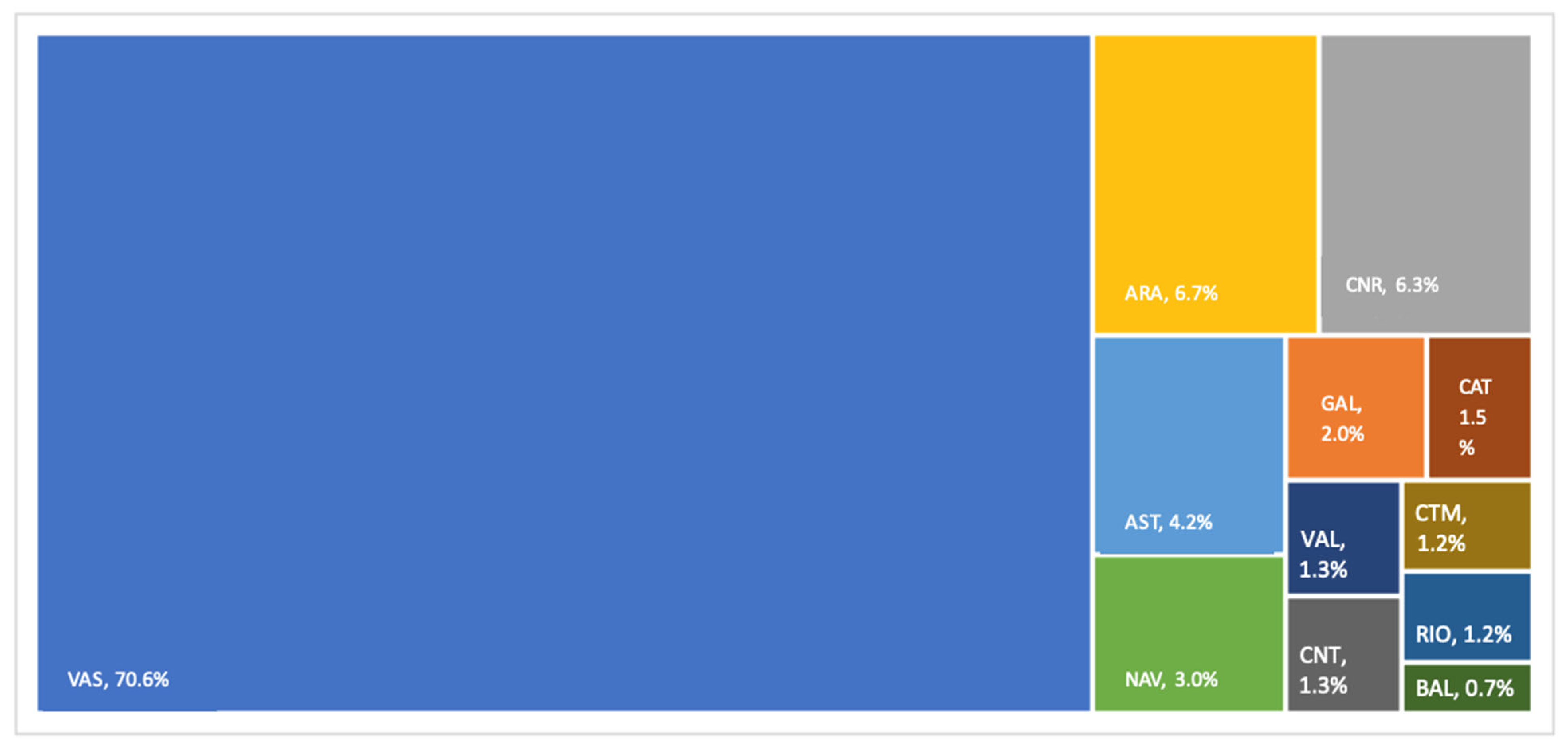

Fieldwork began with counting the datasets that each autonomous community disclosed (

Table 1).

Table 1 shows the autonomous communities ranked according to the total number of datasets.

This initial collection of information shows that the total autonomous community offering is quite significant, as it is close to 40,000 datasets. In the analysis of

Table 1, the uneven content offered by each respective autonomous community stands out. The Canary Islands stand out positively with 20,856 datasets and the Basque Country with 12,493, contributing 44.26% and 26.51%, respectively (which together means that these two autonomous communities comfortably supply more than two-thirds of the national total). At the opposite end of the spectrum is Extremadura, whose 13 datasets account for less than one-thousandth of the total.

The distribution is particularly uneven, as the expected average of 2772 datasets per autonomous community is only exceeded by three autonomous communities (the Canary Islands, the Basque Country, and Aragon), while fourteen are below the average. Obviously, this has an impact on the dispersion measures of the sample, whose standard deviation is 5482 (approximately double the value of the mean).

However, given that the focus of this research is on the datasets related to housing,

Table 2 shows the autonomous community summary by category.

Table 2 only includes thirteen of Spain’s seventeen autonomous communities. The reason for this is that four of them—Extremadura, Madrid, Murcia, and Castile and Leon—did not have datasets labeled in the housing category, so they were obviously not included in the rest of the study, which focused on analyzing this category of information.

On the other hand,

Table 2 reveals an interesting observation about the labeling of datasets, namely the heterogeneity in the interpretation of the standard by authorities of the autonomous communities when categorizing datasets for digital portals. In this sense, some autonomous communities applied multiple labels to their datasets (for example, the total offer of the Basque Country is 12,493 datasets, while the sum of the content of each category exceeds 20,000), such as the Valencian Community that performs it in a unique way (the total coincides with the sum of the categories) and others that have uncategorized datasets (such as Cantabria whose total offer is 291, while the sum of categories is 171).

Having made this comment, the content provided by the autonomous communities that offer datasets labeled under the category of housing is detailed below, in order of the total number of datasets labeled as housing (

Table 2). Although this review is lengthy and tedious (and could well have been placed in an appendix to the research), it is considered particularly important in order to illustrate the reality and peculiarities of the offer from the autonomous communities.

4.1. Basque Country

Its autonomous portal contains 568 datasets within the housing category, making it the autonomous community with the most data available, almost quadrupling the labeled data of the second-ranked autonomous community, Galicia. However, many of these datasets do not contain information at the autonomous community level, such as the 114 datasets of the cadastral parcel at the municipality level or the urban planning approach (all offered by the Provincial Council of Vizcaya); others containing information on buildings (seven from the city council of Bilbao and one from Alava); and finally, a small group of datasets unrelated to housing such as “Basque society facing the future” and “GED: Demographic Survey Manager.”

Once this information was excluded, the remaining 423 datasets were provided by two data suppliers, EUSTAT (the Department of Statistics) and the Basque government, with no apparent difference in the content of each provider. In both cases, recurrent information, i.e., that which is updated every year or quarter in a new dataset, was therefore considered appropriate to proceed with the review by content blocks.

The first block collects the characteristics of both persons living in rental households (xls and csv), and needy dwellings (a dataset for 2005 offered in xls and another for 2006 offered in pdf) or non-mainstream dwellings (xls and csv).

A second block is related to housing. Specifically, a dataset is offered on the quantification of the need for access to housing in the autonomous community (xls and csv), together with seven other varied datasets that measure the demand for housing at different periods (1, 2, and 4 years) for the years 2005, 2006, and 2007, formulated in xls or pdf. Also related to buildings, “Building, residential and housing” is available in ods, and nine others relating to the buildings of the autonomous community by territorial areas that segment the information (by the state of the building, by its destination, by year of construction, etc.) are available in csv and xls. The following refers to “emancipation and housing” available in a wide range of formats (xml, xls, json, jsonp, and csv) and to “distribution of municipally owned housing in the autonomous community of Euskadi by historical territory and use”. Finally, there are twenty-five datasets that begin with the word housing: three on used housing for sale (years 2005–2007); two on planned housing; ten on family housing; three on free rentals; and six that offer information by territorial areas, neighborhoods, or municipalities.

Surveys occupy the third place with thirty datasets. The first dataset concerned rental households (xls), five others on housing needs (period 2008–2013), and twenty-four on real estate supply offered by quarters within the period of 2008–2013.

The fourth grouping, the most numerous, is made up of statistics. Sixteen datasets, mostly available in CSV and XLS, are related to building or housing, offering the information by quarters within the period of 2011–2015. Thirty-seven others concern housing starts and completions (one dataset per quarter for 2016–2024), accompanied by two summaries: “housing starts and completions statistics 1990–1999” and “housing starts and completions statistics 2000–2009”. Finally, twelve datasets on real estate registration statistics are provided (one dataset per year within the period of 2012–2024), mostly in csv and xml. One hundred and eighteen statistical tables are also found, such as twenty-four on building and housing (quarters in csv and xls or years up to 2022 in xls), six on housing needs and demand survey, another six on housing use (one dataset biannually in the 2015–2023 series), and twenty-four on the real estate supply survey (csv and xls) with quarterly or annual information for the period 2013–2021.

In fifth place, eighteen datasets called evolution deal with both housing supply and price, with information relating to the years 2005, 2006, and 2007.

The sixth block is also very numerous as it is made up of 102 datasets relating to financing: housing and land protection actions (one dataset per quarter for the period 2014–2024 available mostly in csv and xls); the loans approved in this regard; the loans formalized; and the subsidies recognized (all three offer a dataset on a quarterly basis for the period 2007–2011 in pdf).

Seventh, twelve datasets stand out as municipal sustainability indicators: average age of family homes, comfort index, etc. (lod, api rest, xls, pdf, and csv); the technical inspection of buildings (same formats); two licenses for major works (xls and csv) houses need or reasons for such need (years 2005–2006); three of renters (xls and csv); three of average housing price; and three on the average monthly rent. There is also a registry of public housing and the monitoring of housing policies (both in zip).

The review of the Basque Country ends by pointing out four datasets on households, all in XLS and CSV, and three on renting (socioeconomic characteristics, useful area, and monthly rent), accompanied by households by year according to the type of housing need. It ends with “Hollows in normal buildings”, which offers information on the census of buildings and their number of floors and hollows; Bizilagun Appointment, an entity that advises on the rights and duties of owners, landlords, or neighbors (zip); and “comparative of loans formalized by financial institutions” (pdf, xls, and csv).

4.2. Galicia

This autonomous community groups information about territory, housing, and transport into a single category, but it is curious that some information is not related to any of the three categories, such as “Galician blue flag beaches” (offering data from several years), “deaths”, etc.

It was necessary, therefore, to conduct a manual review of the 153 datasets to extract those with content regarding dwellings. The review begins with two datasets of statistical information (which have not been recently updated): “Survey of household living conditions: housing register”, which in txt format offers one dataset per year within the series 2007–2012, and “Structural household survey. General module”, which offers a dataset for the 2014–2021 series in xls format.

Referring to expenditure, the following are available—“Average monthly household expenditure on rent of main dwelling” and “Average monthly household expenditure on mortgage of main dwelling”—accompanied by four lists: “Households that have expenditure on mortgage of main dwelling”, “Households that have expenditure on rent of main dwelling”, “Households according to monthly income interval” and “Households according to household typology broken down” (all six offered in csv and xls). With the same purpose, there is “Number and surface area of buildings and dwellings by type of construction” or “Construction statistics of buildings or dwellings that have certain”, both available in csv and xls.

Finally, and with the aim of providing information on housing, two sets of data are offered: “News of the Galician Institute of Housing and Health” (rss) and “Permanent advertising of second transmission housing” (html and pdf).

4.3. Canary Islands

This island is an autonomous community that offers the largest number of datasets at the national level; however, for the subset of data on housing, it is in third place after the Basque Country and Galicia.

Of the 145 datasets labeled in this category, a large number of datasets were found that did not seem to fit there, highlighting the 69 datasets relating to active social security registrations, four on registered employment, and other more general ones such as consumer price indices or a certain economic macro-magnitude. Despite the above, there is abundant information on housing, all offered in json, xml, tsv, csv, and xls formats, which are summarized below.

There are four sets of data relating to buildings: “Characteristics of buildings with partial demolition works by Canary Islands provinces and years”, “Characteristics of buildings with total demolition works by Canary Islands provinces and years”, “Characteristics of residential buildings to be constructed by Canary Islands provinces and years”, and “Characteristics of non-residential buildings to be constructed by Canary Islands provinces and years.”

This information is provided together with nine other datasets that quantify buildings or dwellings. As for the buildings, the following are indicated: “Number of non-residential buildings and surface area to be constructed according to destinations by provinces of the Canary Islands and years”, “Number of buildings according to types of work by municipalities of the Canary Islands and years”, “Number of buildings according to types of work and destinations by islands of the Canary Islands and years”, “Number of buildings according to types of work and destinations by provinces of the Canary Islands and years”, and “Number of buildings according to types of work and destinations-Spain and autonomous communities by periods”. Regarding housing, the following were found: “Number of dwellings of new construction, extension or refurbishment -Spain and autonomous communities by periods”, “Number of dwellings by type of construction by Canary Islands and years”, “Number of dwellings by type of construction by municipalities of the Canary Islands and years”, “Number of dwellings by type of construction and destination by provinces of the Canary Islands and years”, and “Number of dwellings by type of construction -Spain and autonomous communities by periods.” Finally, a dataset containing both terms was found: “Number of buildings and dwellings according to types of developer, -Spain and autonomous communities by periods”.

Next, four other datasets regarding operational concepts of statistics are highlighted: of appraised value of housing, of construction of buildings, of official bidding in construction, and of construction management visas and housing price index.

As for licenses, these datasets were “Number of municipal licenses for major construction work granted according to types of work by Canary Islands and years”, “Number of municipal licenses for major construction work granted according to types of work by Canary Islands municipalities and years”, and “Number of municipal licenses for major construction work granted according to Canary Islands provinces and years”, together with another five sets of data on tenders: “official tender in construction according to contracting agents and extended classification of work typologies in the Canary Islands by years”, “Official tender in construction according to contracting agents and work typologies in the provinces of the Canary Islands by years”, “Official tender in construction according to contracting agents and work typologies-Spain and autonomous communities by periods”, “Official tender in construction according to forms of contracting in the Canary Islands by years”, and “Official tender in construction according to work typologies and extended classification of contracting agents in the Canary Islands by year”.

Next, there are four others with information about mortgages: “Mortgages canceled according to the nature of the property and the lender—autonomous communities and provinces by period”; “Mortgages cancelled according to the nature of the property—autonomous communities and provinces by period”; “Mortgages modified according to the nature of the property—autonomous communities and provinces by period”; and finally, “Mortgages modified according to the type of change in mortgage conditions—autonomous communities and provinces by period”. The following information should be added to this: “New mortgages constituted according to the nature of the property and the lender—autonomous communities and provinces by period” and “New mortgages constituted according to the nature of the property—autonomous communities and provinces by period.”

Subsequently, there is another block related to surface area consisting of six datasets: “Surface area to be extended or rebuilt according to type of work by provinces of the Canary Islands and years”, “Surface area to be built according to destination by Canary Islands and years”, “Surface area to be built according to destination by municipalities of the Canary Islands and years”, “Surface area to be built according to destination by provinces of the Canary Islands and years”, “Surface area to be built according to destination—Spain and autonomous communities by period”, and “Average surface area per dwelling of new construction or extension—Spain and autonomous communities by period.”

Finally, various information is mentioned, such as two sets of data called “Average appraised value of free housing by age of the dwelling—Spain, autonomous communities and provinces by quarters” and “Average appraised value of subsidized housing—Spain, autonomous communities and provinces by quarters”, together with “News from the Department of Public Works, Transport and Housing of the Canary Islands”, “Free and subsidized housing starts and completions—Spain, autonomous communities and provinces by quarters”, “Periods and free and subsidized housing starts and completions—Spain, autonomous communities and provinces by periods”, and “Number of certificates and settlement value -Spain and autonomous communities by periods.”

4.4. Aragon

It has 40 datasets related to housing, which will be discussed below. First, there is a series of datasets on the age of buildings, on real estate according to use, on rural land, on urban land, on the value of real estate, and on cadastral surfaces, which offer information differentiated at the level of municipalities, counties, provinces, or at the autonomous community level (all in csv format).

Secondly, there are datasets called “Buildings, surface area, and housing”, “Municipal building licenses”, and “Building management permits”, all in xls format, which are offered in a segmented manner, either by municipalities, by counties, or by provinces (this last formulation also includes the autonomous community level as a whole).

To conclude the analysis of this autonomous community, various information is reviewed, such as that relating to mortgages: “Distribution of the volume of new mortgage credit and its average duration”, “Average mortgage and average interest rate of new mortgage loans”, and “Average amount of mortgage credit per housing transaction” (all in csv and px formats). Finally, it mentions “Number of housing transactions” and “Average surface area of transferred housing” (csv and px), accompanied by “Housing rental bonds deposited with the government of Aragon” (zip).

4.5. Principality of Asturias

This autonomous community has its own open data repository with an inadequate design, both in terms of the container (portal design) and content (number of datasets), which seem to be the reason for syndicating its datasets directly to the national portal. Therefore, the national portal was accessed at data.gob, and the Principality of Asturias was searched for in order to access the 26 datasets of the housing category, identifying two predominant blocks.

On the one hand, there are six datasets called population and housing censuses in Asturias. The first one offers detailed information at the council level (html), while the remaining five, available in xls, ods, json, and csv and which only contain information up to 2011, mention their characteristics: number of floors, parking spaces, etc.

On the other hand, there is information about the real estate market, with fifteen datasets offered in html (which redirects to a search engine that allows for downloading the information in xls). Four of them contain valuations: the average value (and total value) of free housing transactions, the appraised value of dwellings, and the value of free housing in municipalities with more than 25,000 inhabitants. There are another seven on transfers of properties, land (according to the size of the municipality or according to the nature of the purchaser), and dwellings (according to the nationality of the purchaser, according to the type of dwelling, or according to regime and state), completing the information in the dataset “Real estate market in Asturias: properties and dwellings transferred according to nature and title of acquisition”. Two others deal with prices (average price of urban land according to the size of the municipality) and the housing price index (according to type), completing this block on the stock of unsold new housing and the evolution of the average area of the transferred dwellings.

The remaining datasets to complete the 26 datasets offered in the housing category are those relating to energy efficiency certificates of buildings and housing (xls), indicators of the sustainable development objectives of the Principality of Asturias (xls and zip), and municipal building permits in Asturias with monthly data on new buildings (html) and by type of developer (format not specified).

4.6. Autonomous Community of Navarre

The Autonomous Community of Navarre offers twenty-two datasets within the housing category, although three of them present general information such as companies with economic activity in the Autonomous Community of Navarre and two directories (of companies and establishments) that carry out their activities there (csv, json, ods, tsv, xls, and xml).

More relevant to the topic are, first, two datasets containing a census of housing applicants (by characteristics and by place of census registration) available in xml, while the rest refer to housing itself.

Of the latter, the first block to be highlighted (downloadable in csv, json, ods, tsv, xls, and xml) is composed of the total number of housing starts and the total number of housing completions in the Autonomous Community of Navarre. In addition to these two datasets showing the total by years, housing—both started and completed—is offered for the period 1994–2012 (which does not seem to add any usefulness to the previous ones), and two other datasets offer that information broken down by locality accompanied by information on developments (kml).

In terms of subsidized housing, there are datasets on subsidies for subsidized housing (csv, json, ods, tsv, xls, and xml) and on surface area and visas for such housing (both in ods and xls). In addition, there are four datasets related to subsidized housing rehabilitation: started, started by locality, finished, and finished by locality (csv, json, ods, tsv, xls, and xml).

Finally, there is the general building assessment register for the Autonomous Community of Navarre (curiously, there are two sets of data with the same content), one in kmz format and the other in csv, json, ods, tsv, xls, and xml, and the evaluation reports carried out (xls).

4.7. Valencian Community

This autonomous community offers fourteen datasets. Five of them are called “viewers of the Valencian Community”, with information on sensitive urban spaces, and there are three datasets on housing rental prices (price table 2018, average price for 2018 and period 2016–2018) and on accessibility in buildings and organized public spaces. Only the first of the five datasets specifies format (wms, wfs, and pdf) since the rest redirect to a map with the information but does not allow for downloading the results.

There are also two other datasets that do not indicate format: “Integrated sustainable urban development strategy” and “Urban renewal and regeneration areas of the Autonomous Community “ The datasets that complete the offer are “Housing of the public patrimony of the Catalonia: offered and awarded” (csv), “Buildings with more than 50 years old and residential use” (wms and wfs), and “Evaluation report of the building of the housing of the Valencian Community” (wms and wfs). Information on rehabilitation areas is also available (pdf) and programmed rehabilitation residential environments (wms and wfs) as well as the study of universal accessibility in public buildings (wms, wfs, and pdf) and a detailed study of such accessibility conditions (wfs and pdf).

4.8. Catalonia

Catalonia has nine datasets hosted in its portal within the housing category, all of them, except “Census of buildings”, offered in html and offered in a wide formative offer (geojson, kml, kmz, rdf, rss, shapefile, and xml).

Three datasets show historical information on housing: “Housing starts and completions, annual historical series 1990-present”, “Quarterly historical series 2000-present”, and “Official protection annual historical series from 2002-present”. Two datasets are on the average rental price of housing (by the municipality and by supra-municipal area), and the remaining datasets are “Certificates of habitability”, “Actions of the neighborhood program 2004–2010”, and “Areas and zones of reference in terms of housing policy in Catalonia”.

4.9. Cantabria

It offers eight datasets with the label housing, all of them with a rather brief and generic title, which are available for download in html, rdf, xls, pc-axis, sdmx, and json.

The datasets are “Urban land prices”, “Estimated housing stock”, “Real estate transactions”, “Subsidized housing statistics”, “Free housing statistics”, “Housing price index”, “Appraised value of housing”, and “Real estate registry statistics.”

4.10. Castilla-La Mancha

It has a total of eight datasets related to housing. The first two contain information on mortgages: “Mortgage intermediation offices” (ods, csv, json, and pdf) and “Assistance, advice and mortgage intermediation in Castilla-La Mancha” (xls and csv). The following three could favor access to housing: “Housing aid and subsidies” (ods, csv, and json), “Aid for urban and rural regeneration and renovation in Castilla-La Mancha” (ods and csv) and “Supply of subsidized housing” (html).

There are also two other related datasets: “Entities for quality control” (xls and csv) and “List of testing laboratories for building quality control declared in Castilla-La Mancha” (ods and csv). Finally, there is the “Statistics Service Database” of general content as it is labeled in the 22 categories included in the technical standard for interoperability.

4.11. La Rioja

The seven datasets assigned to La Rioja within the housing category are available for download in four different formats: csv, json, xls, and xml.

Firstly, reference is made to the datasets “Certifications of completion-Number of dwellings by developer” and “Certifications of completion-Number of buildings by developer”, which show the evolution of construction activity and the building stock based on the information provided by the building permits and certificates of completion.

Another block of information is related to permits, such as “Visas and new construction management-Number of dwellings by type of work” and “Visas and new construction management-Number of buildings by main destination” or “Municipal licenses-Number of dwellings by type of work” and “Municipal licenses-Number of buildings by type of work.” The last dataset available in this category contains information on housing prices under the heading “New and second-hand housing price index.”

4.12. Andalusia

The main page of the open data portal of this autonomous community only shows twenty direct access icons, corresponding to each of the categories included in the technical standard, with only two missing (energy and housing). However, upon accessing the portal, it was discovered that they do exist as sectors of activity and that they offer a total of five datasets each.

Thanks to this, information on housing can be found, such as “Spatial data (they are cartographic bases) of reference of Andalusia” (wms, wfs, html, shp, and gpkg), “Statistical Yearbook of Andalusia”, “System of indicators for the monitoring and evaluation of the agenda for employment” (csv), “Multi-territorial information system of Andalusia” (csv), and “System of indicators of sustainable development of Andalusia for the 2030 agenda” (csv, html, and json). Unfortunately, it should be noted that none of them have a close relationship with housing.

4.13. Balearic Islands

Although the repository allowed us to consult the general content of the portal in Catalan or Spanish, the detailed information of the datasets is only available in Catalan, so it had to be translated.

The Balearic Islands contains four sets tagged in the housing category: “Residential vacant land 2015”, “Current habitability certificates of Menorca”, Tourist accommodations of Menorca” and ‘Stays and tourist holiday homes of Menorca’, all of them exportable in csv, geojson, kml, kmz, rdf, rss, tsv, and xml.

With the Baleric Islands, the review of tagged information is complete in the category for the thirteen Spanish autonomous communities that have information available. The following section proceeds to analyze the results.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Article 47 of the Spanish Constitution, a central element of the country’s legal system, establishes the right to enjoy decent and adequate housing, attributing to the public authorities the obligation to promote the necessary conditions to make this right effective [

54] and facilitating access to affordable housing through public housing policies. In Spain, where the weight of real estate activities in the GDP has not fallen below 10% in the last fifteen years, it can be seen that housing accounts for an increasing proportion of the disposable income of families, which causes unease and even gives rise to citizen demonstrations.

All of the above is proof of the interest in housing for companies, citizens, and public administrations alike. Therefore, in order to favor efficient decision making in this sector, quality data should be available that can be transformed into information and subsequently into knowledge [

55,

56]. This quality data would favor a commercial boost in infrastructure and the supply of affordable housing, especially for vulnerable sectors such as young people and low-income families, among others.

However, it seems that the problem of open data, which has advanced to be established as the second most advanced pillar of Spanish autonomous open government initiatives [

57], is not with its quantity, since its supply has grown exponentially, but its quality [

58]. This is partly due to the fact that many of the open data portals have not been designed for professional use [

59]. This team of researchers has been developing reports measuring data disclosure in Spain for years, from the first work [

45] to its fourth edition [

44]. In the reports, they identify problems such as a lack of maintenance or updating of data, formats not suitable for reuse, and lack of standardization, which makes it difficult to consolidate data common to different sources.

This research also identifies certain gaps. Firstly, there is deficient attention given to the category “housing” given that only thirteen of the autonomous communities have some dataset labeled in this category of information, which is reduced to twelve after the filtering since the datasets labeled by Andalusia do not contain information in this regard. This statement is aggravated when, of the approximately 1009 datasets identified, a first review and debugging of non-downloadable and poorly labeled datasets, erroneous content, duplicate information, etc., reduced this to 599, leaving the housing category as one of the worst of the twenty-two proposed by the technical standard, with only 1% of the total data offered by the autonomous communities.

Secondly, there is a lack of relevant information on both general issues (such as prices, supply and demand volumes, etc.) and specific issues (such as the dissemination by all the Spanish autonomous communities of the energy certificates for buildings). In this sense, and in line with goal number 11 of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, which aims to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable, it is vital since, although cities barely occupy 3% of the earth’s surface, they account for 75% of carbon emissions and between 60% and 80% of energy consumption [

60]. Smart cities require portals with a large amount of data that can be used by public and private entities to create new services and/or enable the improvement of internal processes [

61]. The push for open data, combined with strategic planning, will drive public and, by extension, corporate policies that incorporate social justice objectives [

62] through initiatives such as affordable housing.

Thirdly, the small number of “common” or identically formulated datasets will complicate the aggregation or combination of information from different suppliers, making automated data processing difficult. Therefore, it is necessary to reduce heterogeneity in the publication of open data [

63]. This “Frankenstein” of Spanish open data initiatives [

43], also highlighted by Curto-Rodríguez in his multidimensional analysis, is also evident here by not being able to identify many datasets with the same content [

46]. On the other hand, the dissemination of housing datasets could be qualified as deficient since only one leading autonomy with good performance is identified (the Basque Country, with a score of 77 out of 100), and three other autonomous communities are around 50%. The difference between autonomous communities is, in general, very high since the average score of 38.65 points is accompanied by high dispersion values: range, 60.04; standard deviation, 17.22; and coefficient of variation, 28.69%.

These findings are in line with other studies [

47,

48], which point out a limited attention and interest in demographic information for marketing (given the high heterogeneity observed) and an unequal attention to transparency through open data, with scores ranging from 0 points in Madrid and Extremadura to 53 in Catalonia [

64].

Based on the conclusions reached in this research, which have been limited to being issued (due to the high heterogeneity observed) as a comparative approximation, similar to the work of Criado et al., (2023) [

65] on the maturity of open public data portals in the public sector, a series of recommendations are made.

Firstly, there is a need for the unification of the criteria for the interpretation of what is indicated by the technical standard of interoperability for the reuse of information resources regarding the fact that each dataset must be classified into ONE of the proposed categories (it cannot be that some autonomous communities label univocally and others multiple or, what is worse, that some do not label their datasets, which makes it difficult to locate the desired information through the built-in search engines). Secondly, there is a lack of standardization in the content, which hinders its aggregation, giving as an example the roadmap developed by local governments (provinces and local entities) for the opening of their data, which shows a minimum set of 80 datasets to be disclosed along with a series of recommendations [

66]. Thirdly and finally, there should be a requirement for an adequate range of formats to meet the requirements of different types of re-users as well as a sufficient formative quality typical of open data initiatives (a file offered in html or pdf should not be considered open data).

The paper concludes by mentioning that there is still a wide margin for improvement. Despite the fact that many hackathons and competitions with interesting prizes are being held for the development of open data if the raw material is not of high quality, this poses an additional challenge in terms of reuse by the various stakeholders involved [

67]. It is essential to recall that these datasets serve as inputs for the development of artificial intelligence tools that can enhance strategic decisions in an increasingly complex business environment [

68] and revolutionize the public sector [

69]. The more information you have and the more data you have, the easier it will be to develop appropriate housing policies.

As future lines of research, the extensive and detailed database generated can be utilized to explore different approaches to the autonomous community reality of open data on housing. It can also focus efforts on one of the subcategories of information proposed in this work. It would also be interesting to develop this exploratory study longitudinally, which would show the evolution experienced. In any case, it is hoped that these studies will show that this is not a missed opportunity, or at least not one that has been sufficiently exploited.