Prior to examining the distinct outcomes for all 27 urban areas, it is important to acknowledge the disparities observed in the assessment of SDG 11.3.1 for the four urban areas of Marrakech, Agadir, Laayoune, and Tangier as they differ significantly in the three studies in which they were included [

8,

9,

10]. In the first study [

8], it was found that all four urban areas deviated from sustainability, with Marrakech scoring 1.13, Tangier 1.61, Laayoune 2.21, and Agadir 2.32 for the SDG 11.3.1 indicator. However, it was found in [

9] that the urban area of Tangier scored 0.98, while Laayoune’s SDG 11.3.1 was 0.76; on the other hand, ref. [

10] found that Agadir urban area scored 0.75 and Marrakech 0.44 for the same indicator, suggesting that all four urban areas remained within the bounds of sustainability. The differences observed can be partially attributed to the use of different spatial resolutions for defining the urban area surfaces, highlighting the importance of utilizing high-resolution satellite imagery. Furthermore, this difference can also be partially attributed to the fact that the measurement of land consumption for urban purposes differed in the distinction between pixels classified as urban lands versus those labeled as rural and excluded from the calculation. In ref. [

8], the land appropriated for urban use was represented by the 1 km × 1 km grid cell with an ISA greater than 5%, which overestimated it and resulted in higher SDG 11.3.1 values. This method also introduced a compensating effect by considering the population of the rural areas included in the census but not accounting for its footprint on land. However, although compensating for each other, these two biases resulted in higher SDG 11.3.1 values, primarily due to an overestimation of the urban land consumption component. Nevertheless, while utilizing a larger land area in LCR calculations may introduce a certain level of bias, it is important to note that this bias is consistently applied at both the starting and ending points of the computation. Consequently, this bias tends to cancel out to some extent when calculating the final SDG 11.3.1 score. Therefore, the impact of this bias on the final score is less significant.

3.1. SDG Indicator 11.3.1 and Morocco’s Administrative Regions

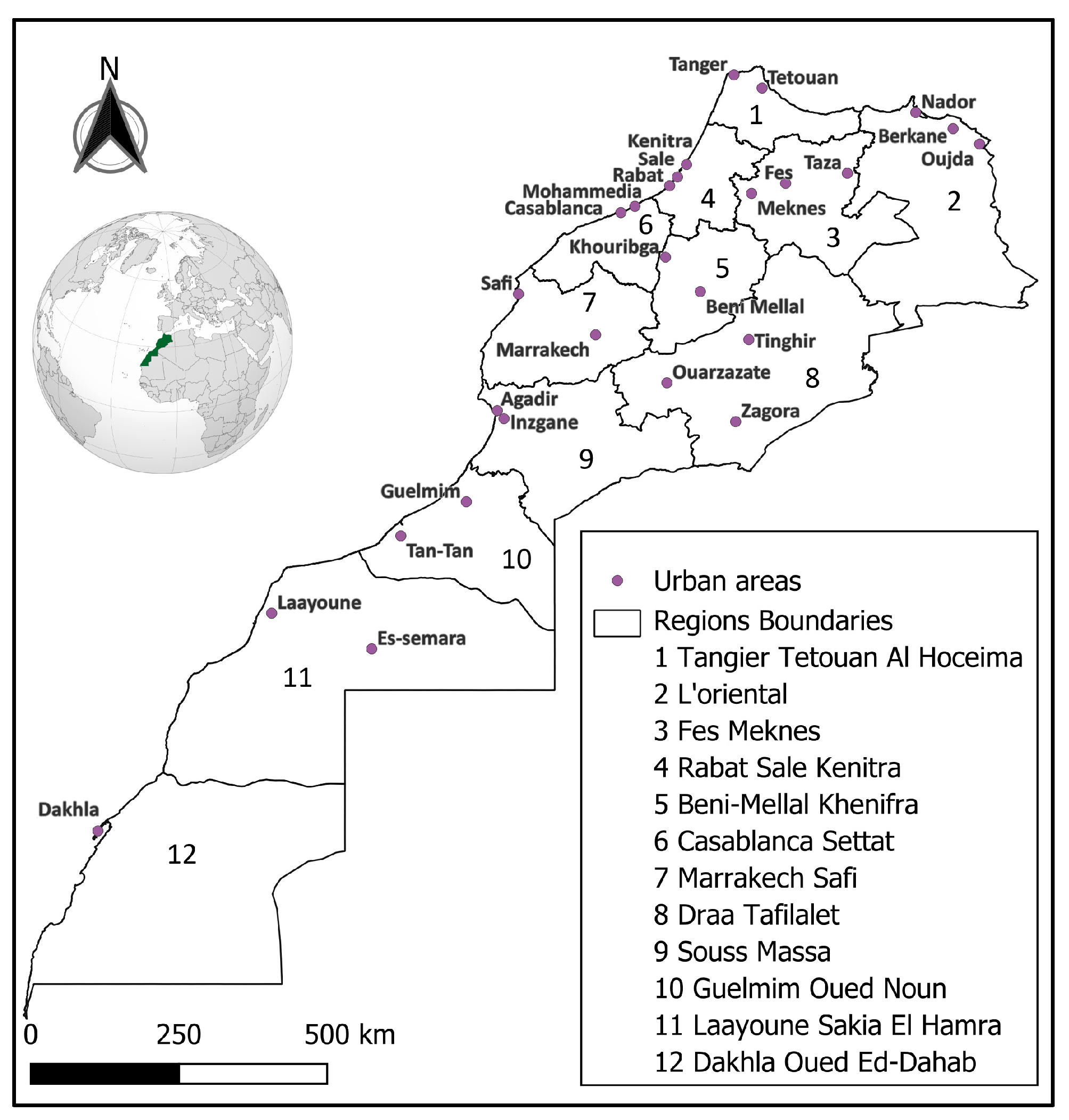

This review encompassed urban areas from all twelve Moroccan administrative regions (

Figure 1). The forthcoming section will examine the urban sustainability status of urban areas within each region. We will begin with regions where all of the urban areas included in this review demonstrated sustainable urban development per SDG 11.3.1 and conclude with the administrative regions in which no urban area has managed to avoid a decline from the initial state of urban sustainability.

Table 2 presents an overview of these statistics.

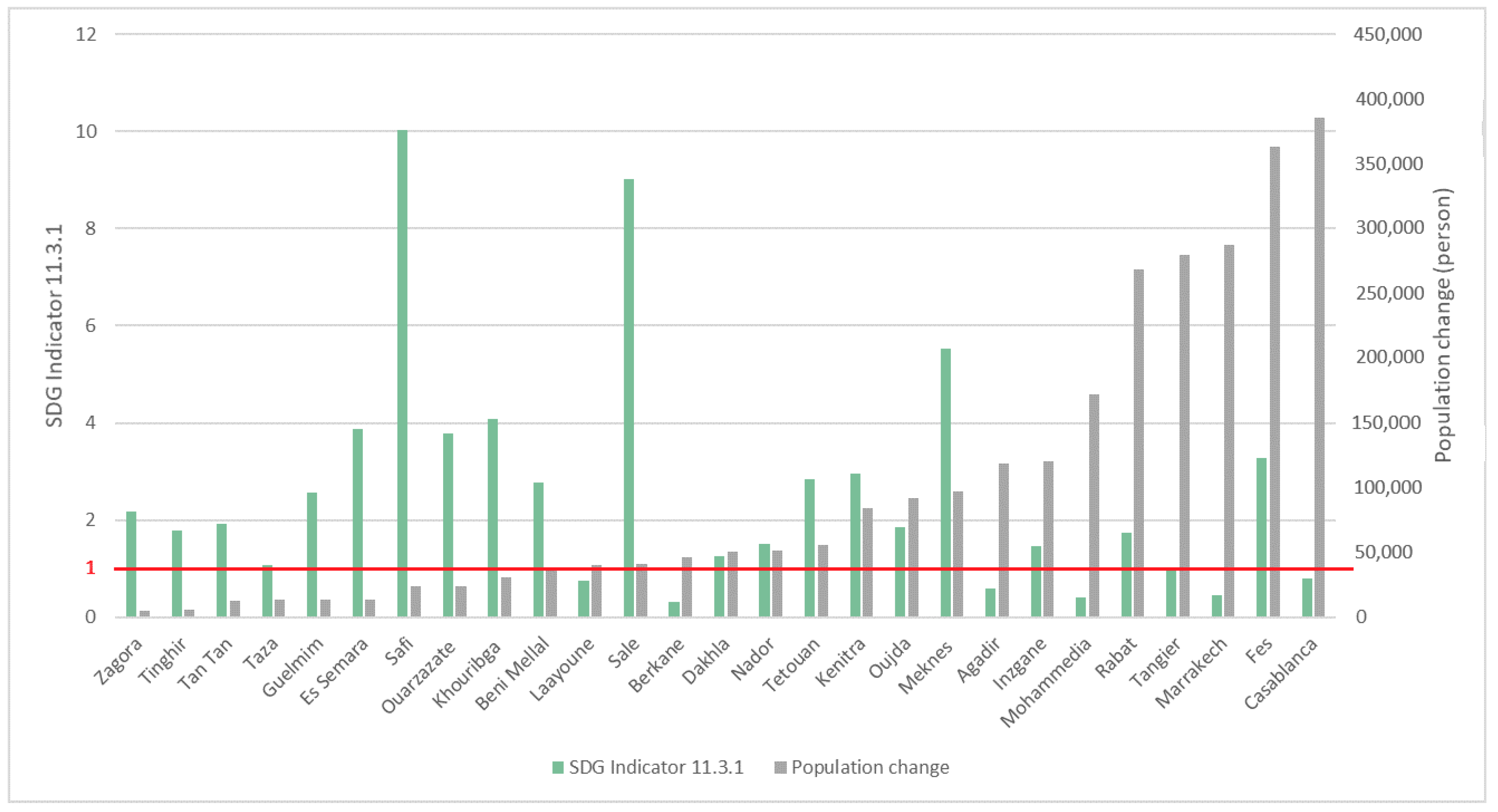

The Casablanca-Settat region was represented by two urban areas: the economic capital of the Kingdom, Casablanca, and its neighbor to the north, Mohammedia, with both scoring an SDG Indicator 11.3.1 lower than the neutral value of one, implying their trends towards urban land consumption sustainability. Located on the Atlantic coast of western Morocco, Casablanca has a population of about 3.71 million (ca. 2014) in the urban area and over 4.27 million in Greater Casablanca and is expanding more horizontally than vertically. Casablanca is a large financial center in Africa where the leading Moroccan companies and many foreign corporations doing business in the country have established their headquarters and main industrial facilities. Therefore, real estate is expensive and a large part of the working population overflows to the neighboring Mohammadia to the north. However, this inter-urban migration has slowed due to an increase in housing commodity prices in Mohammadia following the surge in demand. As expected, Casablanca and Mohammadia are amongst the urban areas with the smallest SDG indicators with a land consumption rate much lower than population growth rate and hence a sustainable urban development.

The regions of Tangier-Tetouan-Hoceima, Souss-Massa, Marrakech-Safi, and Laayoune-Es Semara were represented by two urban areas each. Within these regions, a notable divergence in sustainability trends was observed between the two urban areas, with one exhibiting a positive trajectory towards sustainability per SDG 11.3.1, while the other exhibited a contrasting trend away from sustainability.

In the context of urban areas in northern Morocco, specifically Tangier and Tetouan, both situated along the Mediterranean coast, we observed disparities in the results of SDG 11.3.1. According to the first study [

8], Tangier received a score of 1.61, which exceeds the neutral value of one. In the second study [

9], Tangier received a score of 0.98, barely below unity. When comparing the urban sustainability in Tangier and Tetouan and seeking to comprehend the dynamics of these neighboring urban areas, it is evident that both scores for Tangier are notably lower than that of Tetouan. Tetouan’s score stands at 2.85, indicating a significant departure from urban sustainability. These discrepancies can be attributed to specific factors. Tangier has undergone significant urban development, positioning itself as the second-strongest industrialized urban agglomeration in the country after Casablanca. This transformation is marked by the presence of robust industrial and economic assets, aligning with the objectives envisioned in the region’s urban development master plan. Prominent among these assets are the Tangier-Med port, the automotive manufacturing hub, exemplified by the Renault-Nissan Tangier Med plant, and various energy, infrastructure, and textile industries. The industrial growth in Tangier was followed by a surge in population migration to the city and notable increases in land prices with a discernable trend towards vertical urbanization. As a result, an increasing number of individuals have sought residence in adjacent urban areas within commuting distance to Tangier, particularly Tetouan due to its comparatively attractive land prices and opportunities, thus affecting the SDG 11.3.1 scores for the two urban areas.

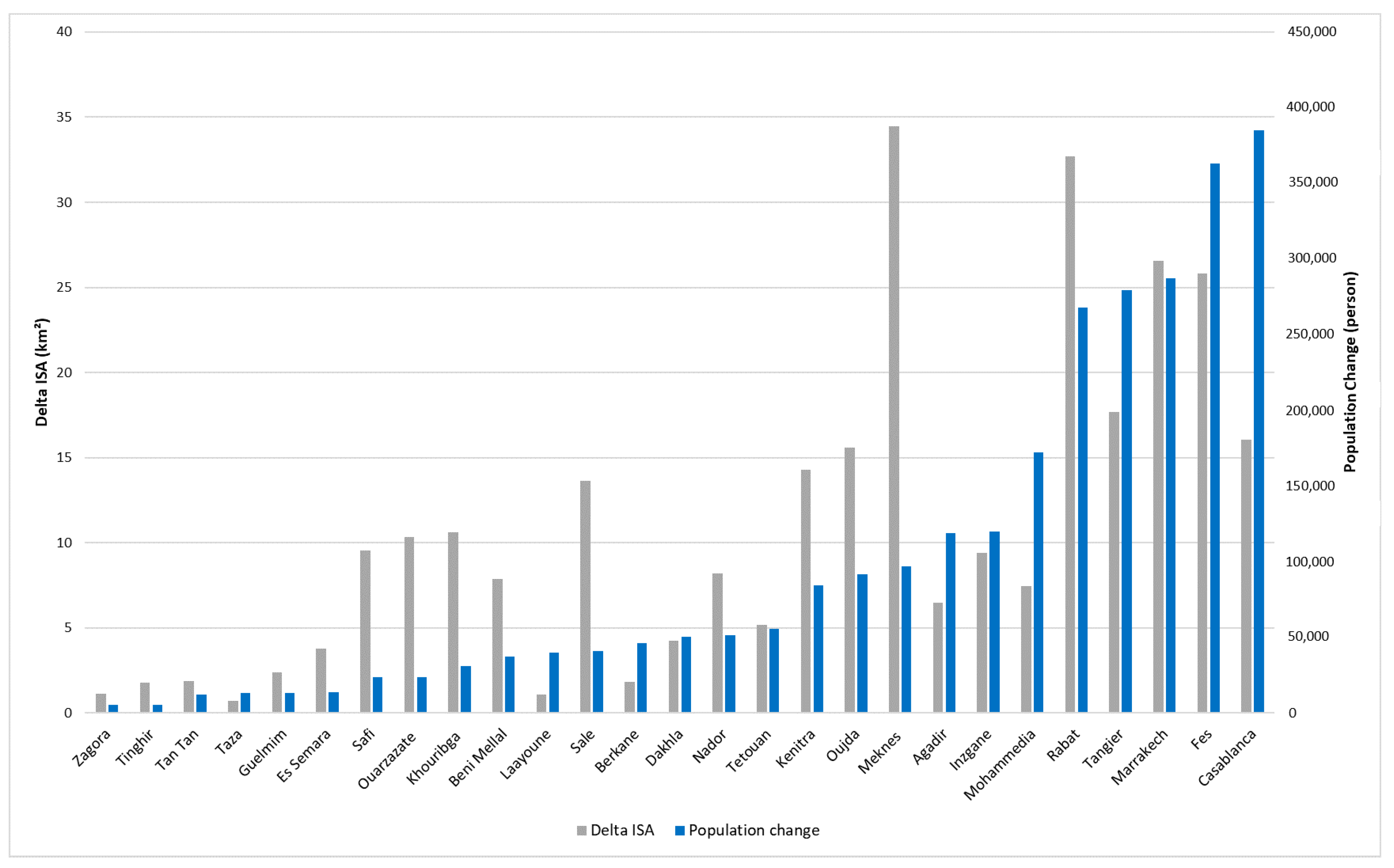

Regarding the Marrakech-Safi region, represented by its two prominent urban areas, Marrakech and Safi, a striking disparity in urban development outcomes is apparent. Marrakech, which experienced an expansion of its urban land area by approximately 26.55 km2 for a population increase of 287,523 people, achieved an SDG 11.3.1 score of 0.44. This score indicates a notable shift toward enhanced urban sustainability and expresses an urban land consumption of about 92 square meter per capita (m2/capita). The increase in urban land use is not only to accommodate the growth in population but rather to account for a substantial physical growth during this period, marked by the construction of new residential neighborhoods, housing complexes, and commercial zones on the urban area’s outskirts. In the inner city, the expansion is clearly evidenced by the construction of modern housing and infrastructure, several hotels, leisure buildings, and roads, all driven by the imperative of accommodating the growing population, but, most importantly, capitalizing on the flourishing tourism industry.

Conversely, Safi, over the same timeframe, expanded its urban land area by approximately 9.55 km2, accommodating a comparatively modest population increase of 23,758 people or about 402 m2/capita. This expansion resulted in Safi attaining an SDG 11.3.1 score of 10.02, signifying an extreme departure from urban sustainability among all the urban areas under this review. The remarkable increase in Safi’s score can be attributed to several factors, including, for a large part, the pronounced growth of the phosphate and chemical industries, cement and textile manufacturing, substantial infrastructure enhancements at the Safi port, and a noteworthy residential expansion. These dynamics collectively led to more than doubling of the city’s urban footprint during the period, surging from 7.66 to 17.21 km2 for a relatively small increase in population count. This is a clear indication that SDG 11.3.1 does not really inform about the relationship between urban land consumption rate and population growth rate alone, and other socio-economic factors need to be taken into consideration in the assessment of sustainability in the urban development.

As far as the L’Oriental region is concerned, its three most populous urban areas during the period of analysis were Berkane, Oujda, and Nador. Among the three, it was found that only Berkane had a sustainable trend with an indicator of 0.31, while the urban areas of Nador and Oujda scored an indicator of 1.50 and 1.85, respectively, reflecting a slight drift from urban development sustainability.

During the considered timeframe, the urban area of Berkane underwent an interesting urbanization and industrial growth. The agricultural sector, particularly the cultivation of citrus fruits, remained a cornerstone of Berkane’s economy, leading to modernization efforts, such as expanded orchards and advanced irrigation systems. The agro-industrial sector flourished with the establishment of processing facilities and infrastructure improvements, including residential infrastructure and road enhancements and transportation network expansions (e.g., Voie Express N6), that were implemented to further support urbanization.

Similarly, Oujda’s urban area experienced a substantial influx of residents, leading to the construction of new residential areas and infrastructure development, highlighted by the expansion of highways and the Oujda-Angad Airport. Oujda’s industrial sector saw growth with the establishment of the “Oujda’s industrial zone”, attracting industries like food processing and textiles to meet rising consumer demands. Educational and healthcare infrastructure expanded as well, such as the extension of the “University of Mohammed I” and other medical establishments. Despite the considerable urbanization Berkane’s urban area underwent, it only expanded by an extra 1.84 km2, accommodating a relatively modest population increase of 46,262 people, an increase corresponding to about 40 m2/capita, and allowed an SDG 11.3.1 score of 0.31, showing a positive trend towards sustainability. In contrast, Oujda experienced much more significant urban growth during the same period, with its urban area expanding by 15.59 km2 and a population increase of 92,129, or an increase of about 169 m2/capita. This resulted in a higher SDG 11.3.1 score of 1.84, indicating a departure from its initial sustainability state.

The Dakhla-Oued Eddahab region, situated in the extreme southern part of Morocco, was represented by a single urban area, Dakhla. Dakhla is notable for its thriving fishing industry and aquaculture activities that experienced expansions and modernization during the study period. Additionally, the Dakhla port underwent upgrades and expansion to accommodate increased shipping traffic and facilitate seafood product exports. In tandem with these industrial developments, Dakhla’s strategic coastal location along the Atlantic Ocean and its natural scenic beauty attracted both tourists and investors. The city witnessed tourism infrastructure, including hotels, resorts, and recreational amenities. Notably, Dakhla’s urban area achieved an SDG 11.3.1 score of 1.26 slightly exceeding unity, indicating a modest deviation from the region’s initial urban development sustainability level, following its urban revival.

The Guelmim-Oued Noun and Beni Mellal-Khenifra regions were each represented by two urban areas, namely Guelmim and Tan Tan, and Beni Mellal and Khenifra, respectively. In both cases, the SDG 11.3.1 scores for these urban areas exceeded unity, denoting a drift away from their initial level of urban sustainability.

Among the twelve administrative regions included in this review, the remaining three—Fes-Meknes, Rabat-Sale-Kenitra, and Draa Tafilalet—had ranked last in in terms of urban development sustainability as defined per SDG 11.3.1. They were each represented by three different urban areas, however, none of the urban areas within these regions achieved a score lower than the neutral value of one (

Figure 5).

As we contemplate the major events that have marked the present landscape of Rabat’s metropolitan area, a detailed examination of the trajectory chosen among other possibilities becomes imperative. Rabat, as the capital of the Kingdom, received a special attention with regard to infrastructure development and economic optimization. This advancement brought along ongoing projects which had affected the housing market prices that consequently became over the reach of even well-off social classes [

23]. Under such circumstances, people were forced to look for more affordable housing alternatives elsewhere; thus, new settlements started to rise in the vicinity of the capital. Such settlements included those located in the communes of Ain El Aouda, Sabbah, and Sidi Yahya Zair, census units 3, 13, 14, respectively, in

Figure 1, all three belonging to the administrative province of Skhirate-Temara. The geographical distribution of these new emerging urban settlements took place on a vast area of land, which raises the question on whether there was a possibility for a better urban planning with the aim of lessening the commuting distance, of these now-dispersed urban settings, to the capital Rabat, and carry along other advantages in terms of resources allocation, and infrastructure optimization.

The computation of SDG Indicator 11.3.1, omitting the three aforementioned census units (3, 13, and 14) from the UZI of Rabat, resulted in the reduction in the SDG Indicator 11.3.1 score from the original 1.74 to 1.61, showcasing how, the new impervious surface area introduced in these communes (between 2004 and 2014) negatively impacted the indicator’s result, as land was consumed at a higher rate than population growth. Currently standing scattered, these three urban settlements face many challenges such as smaller-scale economies and limited opportunities for growth, due to the coupling of infrastructure development costs and resource allocation. Adding to that, the higher commuting-related environmental impact and potential fragmentation of local ecosystems raises ecological sustainability concerns.

Exploring the possibility of having one continuous urban settlement, combining the aforementioned three settlements and any planned urban expansions taking place in the Skhirate-Temara province, with a commuting purpose, should have been a possible alternative pathway that could have some benefits. This approach allows for efficient land use, streamlined infrastructure development, and economies of scale, fostering a central economic hub for the entire Skhirate-Temara province and possibly the entire Rabat metropolitan area. It facilitates cost-effective provision of centralized services, promoting equitable access to shared resources and enhancing social integration. A continuous urban settlement solution could have taken place in the northern part of the Sidi Yahya Zair (commune 14) where the project of the new city “Tamesna” was already launched in 2004 aiming to free some of the housing pressure on Rabat and solve the informal housing problems. However, this project still faces a number of challenges, such as the refusal of many households to participate in the resettlement process [

24], and several private developers exiting the project prematurely [

25]. Examining the shortcomings encountered during the implementation of the latter project and considering the various aspects highlighted in the modeling scenario for a continuous settlement sheds light on a more comprehensive understanding of the complex issue of sustainable urban development.

The urban areas of Tinghir, Zagora, and Ouarzazate, all located in the administrative region of Draa-Tafilalet, underwent noticeable urban land consumption. Tinghir, known for its stunning Todgha Gorges—a natural oasis created by the river Todgha carving its way through limestone with over 400 m in height canyon-walls on the eastern part of the Atlas Mountain—saw an expansion of residential areas and improved infrastructure, including the construction of new housing complexes. Zagora, a gateway to the Sahara Desert, experienced growth in tourism-related infrastructure, such as hotels and desert excursion services. Ouarzazate, often referred to as the “Hollywood of Morocco” due to its role in the film industry, witnessed an expansion of its film-related infrastructure. The entire Draa-Tafilalet region saw infrastructure improvements, including new roads extension and renewable energy projects, contributing to its economic and urban development. However, this development occurred at a rate much higher than the population growth in the three urban areas, leading to an SDG 11.3.1 score exceeding the neutral value of one, especially in Ouarzazate.

3.2. SDG Indicator 11.3.1 and Urban Land Value

The 27 urban areas included in this review were categorized into three distinct groups based on their land value. The first category comprised six urban areas, including Casablanca, Rabat, Fes, Tangier, Marrakech, and Agadir, which are considered the most important urban agglomerations in their respective administrative regions. Among these urban areas, Casablanca, Rabat, and Fes each had a population exceeding 2 million, while Tangier, Marrakech, and Agadir had populations surpassing 500,000 people circa 2014 [

22]. These areas hosted high levels of tourist attraction and significant socio-economic development in addition to high level of public services such education, transportation, and health care, with all of them being considered among the most important metropolitan areas in the country. Consequently, land value in these urban areas is the highest in Morocco. Out of the six urban areas included in this class, Agadir, Casablanca, Marrakech, and Tangier showed a positive trend towards sustainability according to SDG indicator 11.3.1.

In the context of densely urbanized areas, characterized by high levels of prior development—such as those in this category—horizontal expansion manifests as the outward extension of urban boundaries, meaning the consumption of additional land horizontally. This pattern of expansion frequently encounters physical constraints, ranging from natural geographical features such as the Atlantic Ocean limiting the expansion to the west of the capital Rabat, Casablanca and Agadir, and the Mediterranean Sea, limiting that to the northern side of the urban area of Tangier. Consequently, land within the urban area limits becomes increasingly scarce and costly. In response to these challenges, verticalization emerges as a natural response to mitigate the limitations and cost associated with horizontal expansion. However, while verticalization offers the potential for increased housing capacity, it often comes at the expense of quality of life due to densification and overcrowding. This can lead to various problems such as increased traffic congestion, reduced green spaces, and decreased privacy, challenging the overall livability of these metropolitan urban settings. Simultaneously, it encourages people to explore commuter urban areas for more affordable housing options. The SDG 11.3.1 scores obtained for Casablanca, Tangier, Marrakech, and Agadir may be significantly influenced by the dynamic interplay of these factors.

In this context, the focus of SDG 11.3.1 on urban land consumption and population growth fails to adequately address the critical issue of overcrowding within growing urban areas, thereby overlooking a significant aspect of sustainable urban development.

When evaluating urban sustainability in Rabat, the capital city, we observe significant disparities compared to the previous four urban areas. These variations are remarkable, even though the capital shares common attributes of being densely populated and highly developed. These characteristics lead to an upward trend in land costs, which, in turn, indirectly influences the promotion of more vertical urbanization. Rabat achieved an SDG 11.3.1 score of 1.74, surpassing the neutral value of one. This outcome can be partially attributed to the decision regarding the definition of its UZI. To mitigate the peculiar effects of negative population growth, the UZI encompassed not only Rabat but also the census units from the commuter urban areas of Sale and Skhirate-Temara (

Figure 3). Additionally, the presence of numerous governmental buildings in the capital including the parliament, ministerial headquarters, embassies, and consulates, introduces a bias into the indicator, because the relationship between population growth and urban land consumption becomes disjointed, as individuals employed in these institutions or benefiting from their services may often be censed elsewhere. Expanding on this concern, it is worth noting that a substantial portion of academic buildings in Rabat faces a similar situation. Many of these facilities are not solely used by residents of Rabat but also by scholars commuting from Sale and Skhirate-Temara. Sale, for instance, has only one public university, specializing in law, economics, and social sciences. In contrast, Skhirate-Temara lacks any public universities, forcing a large number of students pursuing various scientific disciplines to commute to institutions located in Rabat. These factors collectively contribute to the complexity of assessing urban sustainability and underscore the importance of carefully defining the metrics that inform such evaluations.

The urban area of Fes stands out in this category, exhibiting a relatively high SDG 11.3.1 indicator score of 3.28, which indicates a departure from its initial sustainability. Several factors contributed to this shift in Fes’s development. Notably, rapid population growth drives increased housing demand, land consumption, and infrastructure pressures within the urban area. Additionally, limited appealing commuter options, mainly Meknes and Sefrou, influenced residents to settle within Fes itself. Confronted with challenges like the swift urbanization, the expensiveness of access to affordable formal housing, and economic constraints, residents and migrants from neighboring rural areas resorted to informal housing solutions. This led to the proliferation of a number of slums, including Ain Smen and Dhar El Mehraz, which were later on taken down and projected to be subject for replacement by formal urban development infrastructure.

Overall, it can be inferred that land tenure in these urban areas, which are considered capitals in their respective administrative regions, made vertical urban expansion choice more preferrable because it provides affordable housing, leading indirectly to patterns of urban sustainability as defined by SDG 11.3.1.

The second category comprises eight urban areas: Meknes, Oujda, Kenitra, Sale, Tetouan, Nador, Safi, and Mohammedia. These urban areas had relatively lower land costs compared to those within the first category and were characterized by limited tourism and a relatively modest level of economic activity. Except for Oujda and Safi, most of the urban areas in this category primarily functioned as commuter towns, offering affordable housing within reasonable distances of metropolitan centers. Interestingly, seven out of the eight urban areas in this category displayed a concerning trend toward unsustainability with only Mohammedia’s urban area managing an SDG 11.3.1 score lower than unity. Notably, Sale and Safi stood out with exceptionally high SDG 11.3.1 scores, recording values of 9.01 and 10.02, respectively, indicating a significant departure from initial sustainability levels. The previous section delved into the factors underlying the remarkable score of the urban area of Safi.

In parallel, the urban area of Sale, while already shouldering the responsibility of serving as the primary commuter city for the Moroccan capital, Rabat, boasts a diverse array of thriving manufacturing sectors. These encompass pharmaceuticals, textiles, food processing, chemicals, construction materials, and the preservation of traditional handicrafts. The ever-growing weight of the population influx attracted by the latter elements has contributed to the city’s extreme SDG 11.3.1.

Mohammedia, however, stood as an exception in this second category with an SDG indicator of 0.41. This is most likely due to the economic opportunities present in Casablanca and the rise in its land value. The relatively affordable housing in Mohammedia and its proximity to Casablanca led to fast occupation of its available land, which is expected to increase in the near future. This will lead to a horizontal urban expansion, expressed by an increasing indicator value. At some point, the land will reach an unaffordable value and vertical urban expansion becomes preferable. New other urban agglomerations may form if the original drivers of urban expansion continue to prevail.

The final category comprised the remaining 13 urban areas: Guelmim, Berkane, Tinghir, Tantan, Khouribga, Es Semara, Dakhla, Laayoune, Beni Mellal, Ouarzazate, Zagora, Taza, and Inezgane. In this category, land value has lower price tags compared to the previous two categories, and their industrial sectors are not robust. The population of these urban areas did not exceed 250,000 people ca 2014, with only one exception of Inezgane, which had a population of 514,630 [

22]. Out of these 13 urban areas, 11 showed a trend of moving away from sustainability. Only Berkane and Laayoune had a SDG 11.3.1 score below neutrality. The pattern of drifting away from urban sustainability in this final category can be attributed to the combined effect of affordable land value and the cultural preference of residents from smaller towns to live on relatively larger single-family houses and farm-like dwellings rather than in multi-family residential buildings that are prevailing in metropolitan areas.

3.3. SDG Indicator 11.3.1 and Climate

Morocco’s favorable geographical location in North-West Africa grants it a diverse range of climates, spanning from the humid Mediterranean climate in the north to the arid Saharan climate in the south. This diversity highlights how Morocco’s urban areas experience a spectrum of climate patterns.

The arid Saharan climate prevails in six urban areas—Dakhla, Zagora, Laayoune, Es Semara, Ouarzazate, and Tinghir—where the winter nights are cold, but the days are hot, and with summer daily average temperatures around 35 °C. Five out of the six urban areas had an SDG Indicator 11.3.1 higher than unity, at the only exception of Layounne, scoring lower than one. This describes the somewhat general tendency of the urban population in the arid south to use more land per capita than in the north and is intrinsically linked to their lifestyle and culture. The economy in these areas is based mainly on agriculture, livestock and fisheries, but is currently moving towards tourism infrastructure investments and small to medium industries. These recent developments have also created a situation where urban development seems to trend away from sustainability. This observation was further substantiated by a separate study that evaluated the same sustainability indicator in Algeria, the neighboring country to the east of Morocco. The study focused on five major wilayas in Algeria, which included the urban area of Ghardaia, located in the northern region of the arid Sahara Desert. The findings of their research indicated that out of the twelve communes comprising the Wilaya of Ghardaia, seven showed a discernible departure from sustainability [

26].

The semi-arid climate is predominant in twelve urban areas, including Agadir, Marrakech, and Berkane, having an SDG 11.3.1 score lower than unity, whereas the two urban areas of Inezgane and TanTan did not drift far away from sustainability as their indicators rose relatively slightly over the value of one, scoring 1.46 and 1.91, respectively. On the other hand, the urban areas of Guelmim, Beni Mellal, Fes, Khouribga, and Meknes had an SDG 11.3.1 score well above the value of one. The urban area of Safi had the highest indicator 11.3.1, score of all the urban areas.

Finally, the last category falls under a sub-humid to humid climate and had relatively lower SDG 11.3.1 scores when compared to other urban areas under different types of climate. Out of the eight urban areas in this category, the three urban areas of Casablanca, Mohammedia, and Tangier had SDG 11.3.1 scores lower than one. Moreover, the urban areas of Taza, Rabat, and Nador had scores ranging between one and two, implying a slight departure from sustainability. The urban area of Tetouan and Kenitra have an urban development that is deemed unsustainable with indicator values of 2.85 and 2.96, respectively. Sale’s urban area appeared to have the most unsustainable development of this category with an SDG indicator of 9.01. This value is partly due to the fact that Sale is a commuter to the Kingdom’s capital Rabat, and where during the studied decade a large fraction of the people working in Rabat have moved to live in Sale. As noted in [

26], the formulation of SDG 11.3.1 does not capture land consumption in capital cities which host government and diplomatic’ buildings, which do not occupy a large fraction, but whose population is not censed in the capital. This study extends this concept to urban areas considered as commuters to a capital city and assesses the sustainable development indicator over an urban zone of interest, as defined in

Section 2.2.

3.5. SDG 11.3.1 Limitations

The definition of SDG Indicator 11.3.1 appears to be based on the concept of urban land consumption being primarily driven by population growth, with a suggestion that sustainability in urban development is closely tied to vertical urban expansion, as overcrowding is not considered. In simpler terms, if a city’s growth occurs more upwards than outwards, the indicator implies a positive trend towards sustainability.

However, this perspective neglects a critical factor—overcrowding—which can substantially diminish the quality of life in vertically expanding urban areas, if not associated with social, environmental, and economic development. Furthermore, overcrowding can exacerbate population density, leading to soaring real estate prices in central urban zones, which creates population hotspots that place intense pressure on public services and green spaces, significantly affecting the three pillars—social, environmental, and economic—of sustainability. Therefore, SDG Indicator 11.3.1 falls short in representing these critical aspects of sustainability.

The SDG 11.3.1 also raises questions about what level of sustainability is achieved, particularly when the initial sustainability status of the urban area is not known. Moreover, the indicator assumes a value of one as a neutral point, signifying that development remains sustainable. However, this assumption is not substantiated, as a score of one merely indicates that sustainability has remained constant from an initial state. This is problematic because the initial condition may have been highly unsustainable to begin with.

The indicator also faces several technical limitations. It is undefined when population remains constant over a study period and uninterpretable when there is a decrease in either population or urban land consumption. Moreover, the indicator registers zero if land consumption remains constant during the measurement period, rendering the result uninterpretable.

Furthermore, the bias issue that emerges in the application of SDG 11.3.1 assessments for capital cities, as previously elaborated, underscores a broader challenge in the indicator’s implementation. This capital city bias is not unique to Rabat or Algiers, and it can be extended to many other capital cities worldwide. Capital cities often exhibit unique characteristics, which underscores the need for a more nuanced and context-aware approach when evaluating their urban development sustainability.

In assessing urban sustainability, it is crucial to consider the distinction between relative and absolute measures. Relative indicators, such as those commonly used in assessing urban sustainability, compare environmental impacts across different entities or time periods relative to a baseline or reference point [

27]. While these indicators offer insights into trends and comparisons, they may obscure the true level of sustainability in its intrinsic form. Conversely, absolute indicators provide a direct assessment of sustainability without reference to external benchmarks, offering a clearer understanding of the actual environmental impacts [

27]. SDG 11.3.1 relies on relative measures, comparing the rate of land consumption to population growth. Adopting an absolute indicator for urban sustainability would enable a more precise evaluation of environmental impacts and better inform decision making to address sustainability challenges effectively.

Considering these limitations, it is imperative to advocate for a new and improved indicator that offers a more comprehensive and inclusive evaluation of urban development sustainability. This new indicator should encompass a broader range of factors that SDG 11.3.1 overlooked. While the current indicator solely considers land consumption and population growth, the proposed metric should include additional dimensions, such as the economic one overlooked by SDG 11.3.1, and include more social and environmental factors, while simultaneously encompassing culture and local identities of cities as they stand firm as integral components of the remedy to the challenges of urbanization [

28]. Additionally, it should adhere to internationally defined standards for urban development sustainability. Such a holistic approach is essential for providing policy leaders and decision makers with a more accurate and insightful assessment of urban development plans and their effectiveness.

Attempts were made to capture the multidimensional nature in assessing sustainability. For instance, in a study investigating the sustainability of 31 Chinese provincial-level administrative regions, a composite sustainability indicator (CSI) was employed, aggregating thirty indicators spanning economic, social, and environmental dimensions [

29]. Another contribution proposed a set of composite indices that cover various dimensions of sustainable development (environment and natural resources, energy transition, sustainable mobility, economic dynamism, social cohesion and solidarity, and governance and citizenship) [

30]. While it provided an evaluation framework for empirically comparing the sustainability performance of 96 metropolitan French departments, the study acknowledged several limitations. For instance, the complexity involved in designing and implementing composite indices means that careful interpretation of the results must be carried out. Additionally, while the indices met the primary requirements of a well-defined composite index, it was explained how the inherent choices in the methodology implemented (variables selection, aggregation methods, and normalization) significantly influence the outcomes [

30].