1. Introduction

Any process of collective change will involve establishing relationships of trust and collaboration. The implementation of Nature-based Solutions (NbS), often in a wider context of urban regeneration, is no exception to this rule. NbS are at the forefront of efforts to tackle urban challenges related to climate change and the associated societal transformations, not only because of the co-benefits they provide but also because they are excellent catalysts for positive change, often being less threatening than other types of regeneration. As cities struggle with structural and morphological issues associated with high urbanization rates [

1], it is commonly argued that NbS need to be locally adapted to a spatial context in which the implementation could yield better societal results, especially when anchored to local community needs and aspirations [

2,

3,

4]. In order to improve the adequacy of NbS actions to localised challenges, it is always necessary to consider the context of the application, including issues relating to political power, as well as consider local attitudes to development and the culture of participation.

Utilising NbS as core catalysts to solving urban design, planning and management issues, especially of a social nature, is a key component of the Horizon 2020 programme [

5]. NbS in this context are an umbrella concept that can be defined as “

actions which are inspired by, supported by or copied from nature. Some involve using and enhancing existing natural solutions to challenges, while others are exploring more novel solutions, …

Nature-based solutions use the features and complex system processes of nature, such as its ability to store carbon and regulate water flow, in order to achieve desired outcomes, such as reduced disaster risk, improved human well-being and socially inclusive green growth…. These nature-based solutions ideally are energy and resource-efficient, and resilient to change, but to be successful they must be adapted to local conditions” [

6].

The applications of NbS in urban planning are diverse and multifaceted; considering their wide ability to bring a diverse range of natural features and processes into cities that deal with multiple urban sustainability challenges simultaneously [

7,

8,

9,

10]. They are considered not just solutions to fill the spaces between buildings for aesthetic value or social activities but can also be reframed as new patterns of urban morphology to maximise their environmental and social benefits [

11].

In this research article, we highlight the importance of understanding the specific contexts of local communities to include them effectively in the co-creation of NbS, associated with urban regeneration processes. Different urban contexts require distinct approaches to maximise inclusion and both deep and wide engagement. Furthermore, NbS are known to be effective catalysts that provide holistic solutions to local problems, especially those that provide co-benefits in both social and biophysical systems, specifically the ones related to the social cohesion and societal challenges [

12]. To increase people’s sense of belonging within their local communities, they are invited to take leading roles in the process of change and be prepared for participation in collaborative governance structures, and utilising NbS as the core aspect of regeneration is an effective strategy [

13]. The fundamental role that nature and NbS play in gathering local communities together to bond with each other and with local natural systems is becoming increasingly clear [

14,

15]. The critical role co-creation takes in the connecting of communities to local nature can have a central role in increasing people’s well-being.

In the realm of community engagement, projects vary in size and duration, ranging from short-term endeavours to ongoing, multi-year initiatives, and the co-creation component of these can evolve into collaborative governance structures over time [

16]. Critical to the early stages of co-creation is the meticulous analysis of context, and the assembly of stakeholders is pivotal to the success of the project. Understanding the nuances of the core communities and organisations is integral, as these entities transition from historically top-down, command-and-control methodologies to more horizontally organised models [

13,

17].

In certain contexts, participatory processes may be novel and welcome; while, in others, prior encounters with development projects and municipal services may have fostered scepticism or apathy. Such a context was encountered in South Thamesmead, and responding to it appropriately was critical to the London approach. Building trust within communities and mitigating negative perceptions require time and a strategic approach. Since 2018, the London CLEVER Cities project has been on the ground, co-creating integrated urban design and nature-based solutions in South Thamesmead. This initiative has explored diverse methods to engage stakeholders, both in terms of intensive project development and broader public consultations, see

https://earth.org/clever-cities-how-to-build-trust-in-communities-for-a-more-sustainable-future/ (accessed on 9 December 2023).

1.1. Research Question

This paper focuses on the London-specific actions that were needed to develop a successful community-led development process in the South Thamesmead region. Thus, this study will be able to report on some of the key learnings with respect to the application of certain co-creation strategies and the implications of these on co-governance and other urban management processes. More importantly, it will focus on the strategies utilised in an urban context in which disbelief, engagement fatigue, apathy and limited social structuring are key challenges to be faced. To this end, the core research question addressed is this: What are key co-creation strategies and enabling factors that can be applied in urban contexts with limited social structuring and high levels of disbelief in regeneration projects and how may these strategies inform co-governance and other urban management processes?

There are key characteristics of a neighbourhood or region that will have an impact on the approaches and actions taken with respect to stakeholders’ engagement, co-creation and the eventual governance structures. In summary, in South Thamesmead, as in many other parts of the region, there were four main aspects that had a lasting impact on the project:

The limited level of existing social structure encountered.

The significant levels of consultation fatigue, distrust and apathy with respect to top-down lead projects.

The relatively compact institutional context within the Peabody housing association as the main landholder.

A relatively recent history of experimentation with community-led development projects.

This paper focuses on items 1 and 2 and how responses to these contexts were critical for effective co-creation and for the consolidation of other aspects of urban management. In particular, it is interesting to consider how the foundations of trust and sustained relationships affect the collaborative governance structures, communications and motivational frameworks.

The CLEVER Cities Project Framework

The London South Thamesmead project takes its overall framework from the CLEVER Cities project (see

https://clevercities.eu/ (accessed on 23 November 2023)), funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 programme. The focus of the research project was on the positive changes in social dynamics and the improvements to health and well-being that are associated with co-created NbS. The CLEVER Cities project developed nine sites, with the application of a diverse range of NbS in Milan, London and Hamburg within the timeframe 2018–2023. During the life of the project, many NbS interventions were designed and implemented in extensive co-creation processes with the local communities.

The co-creation process in the CLEVER Cities Guidance (see

http://guidance.clevercities.eu/ (accessed on 9 November 2023)) described the means for involving a wide range of stakeholders in the different phases of urban regeneration including networking, visioning, ideation and detailed design, as well as during implementation and monitoring. The co-creation guidance helped cities plan and initiate engagement processes and promoted the sharing of ideas between cities [

18]. It included tools and methods that proved essential for the successful completion of the co-design phases and the development of co-governance structures. The project utilised an Urban Living Lab (ULL) approach based on developing an Urban Innovation Partnership (UIP) in each city context. The process envisaged CLEVER Action Labs as ULLs that ideally were strategic, civic and organic, and incorporated a wide spectrum of experimental platforms for governance, interventions and change [

19,

20].

Each of the different phases of co-creation that were included in the guidance had to be reviewed for applicability and were often adapted, modified or complemented with new activities. The CLEVER Cities methodology thus provided structure for this process but allowed for the development of specific regional variations. The guidance laid out the basic steps to move through the process. “

The co-creation Pathway in CLEVER Cities is a form of Open Innovation in which ideas are shared, closely connected to user-generated content and actively communicated to allow creativity and shared responsibility. Moreover, co-creation in practice is more about motivating people, inspiring participation, sharing results, continuing development and delivering results at many levels” [

16].

Involving a wide range of stakeholders in the urban regeneration process is necessary to overcome barriers and to validate the decision-making processes. It is important not only to bring forward local knowledge that grounds solutions but also to develop a sense that visions and goals are determined collectively. Having citizens collaborate in co-designing and co-developing the solutions with local authorities, like the housing association, Peabody, and the Greater London Authority (GLA), leads to more diversity of perspectives and solutions, creating a framework that directs focus on social co-benefits of NbS. Different models of decision-making processes can be explored, involving different relationships between governmental, institutional and non-governmental stakeholders. Co-governance structures can emerge and support the goals of co-creation in the long-term by consolidating participation and sharing decision-making power [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

1.2. South Thamesmead Specific Context

Clearly, NbS solve urban problems and bring environmental benefits, and these have been widely documented [

27,

28]. However, the CLEVER Cities project has turned the brunt of its attention to social co-benefits, and these are strongly dependent on the local social and cultural contexts of each ULL. To a degree, this adaptability to local context was expected and included in the guidance: “

The Guidance is intended to be flexibly adapted to different cities’ contexts, inclusive of a diversity of stakeholders, open to all and transparent whatever their scale is. Possible adaptations, hence, are widely compliant and feasible” [

16,

29].

The project started with the documentation of the limited history of community-led design experience in the area. Positively, within the relatively short timeline that Peabody has been active in Thamesmead, there has been increasing community involvement and consultation, as can be seen in the community-led process to develop the Moorings Sociable Club and the Moorings Common Plan. Peabody’s continual investment in the region and programmes like CLEVER Cities have had a further catalysing effect, and progress can already be seen in the region.

However, these recent developments could not fully make up for the past. The local issues in South Thamesmead could not be ignored and required site-specific project solutions. Therefore, the current context for engagement could still be characterised by minimal existing social structuring and limited experience in community-led design in the general population. In this case, there was the need to extend the range and time investment in earlier stages of the co-creation pathway. Specifically, there was a need for significant foundational trust building and relationship development, well before creative co-design and other decision-making activities could be undertaken.

Thamesmead also has the curious political-administrative arrangement of being a region that is divided by two boroughs, but the majority of the London CLEVER Cities interventions lie within the Borough of Bexley. Interestingly, over 60% of the land area is effectively administrated by Peabody, which owns the most critical land sections that have the potential for commercial and housing development as well as much of the blue–green infrastructure.

Thamesmead is a region with historical significance, being originally planned as a model community with the utopic blindness of the 1960s. The lofty goals in the development, like many others of the time, did not live up to the initial visions. Many of the key design solutions were never implemented and those that were implemented were based on concepts that did not capture the real complexities of social interactions.

It is an economically and socially diverse region that has had waves of immigration and significant change over the years, each of which has left its mark on the demographic characteristics of the area. With the new housing planned for the next decade, the social make-up and local demographics will continue to change.

The regeneration plan focused on making connections between the Abbey Way linear park, Southmere Estate and Lake, and Parkview Estate, creating and/or improving the network of green spaces in these areas. The homes that are connected to these open areas are mostly, but not entirely, Peabody owned. There is a mix of rental and privately owned units. The project area borders both existing settlements from the 60s and housing from later decades, as well as a section that is set to be rebuilt (See

Figure 1).

Peabody and its other CLEVER Cities partners, the GLA, Groundwork London, Muf Architecture & Art and the Young Foundation, have led the implementation of green and open-space interventions, highlighting NbS [

29]. In this context, NbS could be defined as public spaces and point interventions aimed at improving the environmental comfort as well as enhancing social factors like safety, cohesion and inclusivity [

30]. These not only aim to consolidate the community experience in those estates, but also to test, with pilot projects, a range of co-created NbS and to explore the social co-benefits of these environmental improvements over time.

The CLEVER Cities project takes an experimental position by exploring innovation in co-creative regeneration processes that are trying to document social co-benefits in NbS projects. The partners were open to determining how best to bring in community knowledge and consolidate community-led decision making. At the heart of the process are the strengthening of the local community ties and understanding how multiple benefits can be generated, including aspects of health and safety, while still improving biodiversity.

1.3. The Importance of Living Labs as Test Hubs for Co-Creation and Co-Governance

Living labs have been utilised as they allow cities to observe urban issues and test solutions in complex and real-life conditions [

18,

31]. The systematic testing and observation of the challenges and benefits of working with different strategies creates the conditions to overcome both ingrained institutional resistances and negative perceptions towards regeneration projects through effective community involvement.

In London, Urban Innovation Partnerships (UIPs) are a CLEVER Cities project version of what are generally known as Urban Living Labs (ULLs), which in the CLEVER Cities context were subdivided into smaller units of action designated as CLEVER Action Labs (CALs). These important units of action gradually established city-specific co-governance structures that brought together communities, designers, and institutional and other stakeholders to capture local knowledge and foster innovation and shared decision making [

31,

32,

33]. The formation of the UIP fulfils the need for an intermediary organisation that can help translate and guide the information found with the citizens to technicians and administrators in the design language format needed for project delivery.

Each city was called to develop its own matrix that puts its stakeholders on the pathway towards co-designing and co-implementing NbS in the context of Action Labs nested in a UIP. By using different methods, such as Rasci models (see

https://www.interfacing.com/what-is-rasci-raci (accessed on 12 December 2023)), network mapping, power-interest matrices and others, stakeholder contributions for specific plans were incorporated in each CAL, including aspects such as describing potential investment, execution timelines and risk assessments [

34,

35]. Thus, the living lab was a critical unit needed to consolidate planning, establish co-governance and provide a context for experimentation and learning.

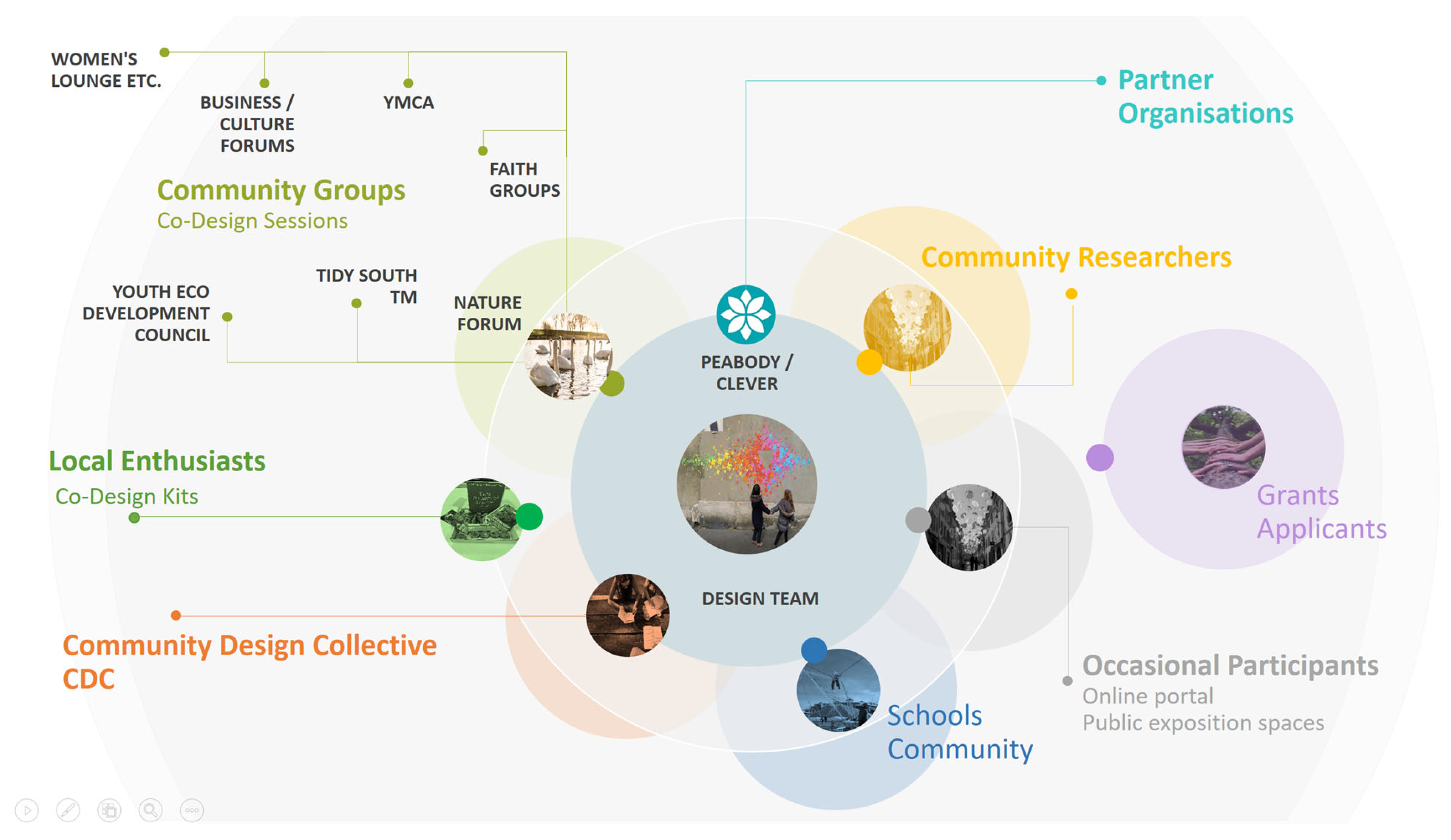

Responding to the distinct context of Thamesmead, London has developed an integrated UIP with thematic focused CALs, in a multi-stakeholder arrangement that allowed for different channels of contribution to decision making (which can be seen in

Figure 2).

Many of these co-governance structures have carried on beyond the CLEVER Cities project and are laying the foundation for significant expansion of community-led processes in Thamesmead. There is a gradual sense of ownership growing, starting with people who have been involved in the Action Labs and reaching out into the wider community, but this will take time. The CLEVER Cities development started by first spending the time and effort to try building relationships and strengthen people’s outlook towards local change. Creating the organisational and social underpinnings for both collective experimentation and active design is the foundation for developing the new governance structures needed in the future.

1.4. Co-Creation and Co-Governance: The Importance of Context

Co-creation methodologies and co-governance approaches are increasingly becoming the standard means of guiding urban regeneration processes, including in the latest European Commission-funded projects [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Effective co-creation is anchored in engaging a diversity of stakeholders in order to collect community-based knowledge and create the channels to document and utilise the information in the decision-making process [

41]. Many ongoing experimental projects are exploring the relationships between socio-political contexts, co-creation and collaborative governance. In fact, this systemic form of research and learning is critical to consolidate effective methodologies that respond to a variety of specific local contexts.

This paper describes some of the key manners in which the CLEVER Cities programme needed to adapt its co-creation methodology to the London context, specifically to South Thamesmead, and to highlight how critical building trust and sustaining relationships can be. The discussion focuses on the lessons learned from the earlier stages of co-creation and considers the impact of these foundational moments on co-governance and other critical processes in later stages. The article explores which strategies and enabling factors were critical in overcoming the challenges that originated in long-term, negative perceptions of top-down, large-scale regeneration projects in the region. The history of ineffective consultation and incomplete projects, together with perceived negative interactions with administrators, has developed into a significant barrier for new community-led processes to take hold. It has been critical to begin to understand and register the local culture of participation, as this will hold the key to overcoming the errors of the past and begin to forge new, genuine relationships of trust with the community. To this end, the principal outputs of this process are the co-creation strategies and the associated learnings of the effectiveness of these in similar contexts, and the consolidated recommendations that can be extrapolated more widely and applied to many other neighbourhoods and cities.

1.5. Building Trust in Thamesmead

The main aspects of the project were determined by the specific social, spatial and organisational contexts found in Thamesmead (see

https://www.thamesmeadnow.org.uk/ (accessed on 15 December 2023)). From a social perspective, it is important to understand that different neighbourhoods and boroughs can develop more diverse social granulation, with many social units above the immediate family (but below the district or borough units) in which people can connect and participate in a more collective, cohesive fashion. This can be achieved by fostering or even creating new social groups in a neighbourhood or district. Social structuring would, therefore, include a rich and diverse third sector with simple local organisations like book clubs or more extensive networks like residents’ associations or even fully fledged nongovernmental organisations that have a presence locally or beyond. This is not typically the case in South Thamesmead, as there was a very limited number of social groups, such as local cooperatives, clubs or neighbourhood groups. Furthermore, there are still very few shops, stores, cafes and restaurants that might help lead to the formation of stronger social ties and result in more local social networking.

Unfortunately, better social structuring across different scales in Thamesmead is, to some degree, restricted by the existing physical layout of the estates and infrastructure in the region. The social function of neighbourhoods depends on the presence of specific social dimensions, street networks, population limits, meeting places and activities that make up the necessary core for community formation. In fact, the layouts of the streets and paths in the estates tend to distribute people over a larger area rather than help bring them into contact with each other, and this is simply not conducive to building social cohesion [

19,

42]. Much of the critical urban spatial support to social life is missing, simply because it was conceived with the urban design knowledge of the 60s, and this legacy works against local social structuring to this day.

From a motivational perspective, although Thamesmead is clearly evolving in many positive ways, it can still be characterised as a region that is recovering from a long period of consultation fatigue and distrust in the authorities. This is clearly associated with the repeated coming and going of different municipal entities and housing associations over the years. As these organisations are perceived to have come and gone without much positive impact, it is still easy to find much apathy and a sense of expecting inaction as the inevitable outcome of top-down projects. Even organisations that are a staple for neighbourhoods, like Tenants and Residents Associations (TRAs), have either not taken hold or have disbanded and faded away over the last decade. The same has been true for other common civil society organisations.

Simply put, the lack of a diverse range of grassroots organisations made the process of channelling community knowledge into the co-creation process inherently difficult. Reaching individuals and households, one by one, is extremely challenging and time consuming. Wide-reaching engagement tends bring in a diversity of ideas and priorities, but it does not take the place of the more intense involvement needed for the detailed decision-making associated with community-led design. And more intense, multi-session engagement is often best realised with relatively stable community organisations.

3. Results

The results presented in this paper originate in the observations and documentation of qualitative research activities, based on the adaptation of the participatory processes of CLEVER Cities to involve local Thamesmead stakeholders, residents and other key actors better.

3.1. Pre-Phase: Determining the Thamesmead Context

The process of forming the UIP in the CLEVER Cities South Thamesmead project was not a linear one. While the formation of UIPs in each of the cities started the process in a relatively standardised manner, there were immediately significant differences from city to city. The UIP is described in the project support material as an “alliance of local and city authorities, community (groups), businesses, academics”, but Thamesmead provided a context that was institutionally relatively uncomplicated due the central role of Peabody and the limited number of institutional stakeholders that would need to give permissions and directives when compared with other cities. The process of mapping and identifying both technical and institutional stakeholders, as well as local grassroots stakeholders, occurred frequently in parallel, with many points of intersection and eventually a phase of consolidation. There were different networks that evolved during the process. With respect to institutional stakeholders, it was possible to map out stakeholders quickly and efficiently from existing Peabody networks, be they internal to the organisation or already partially mapped out by Peabody’s community outreach work. This network mapping helped identify how different groups within and without Peabody were interrelated. Then power-interest matrixes were applied to see the level of possible influence a sector or organisation could have over the process.

The initial analysis showed there were few existing grassroots community groups to bring into the co-creation process. The number and function of local social groups active in the Thamesmead area was not proportional to the population. Contact with initial residents often led to stories of past project failures, a sense of limited capacity to effect change and general distrust in top-down projects. The result was that, in the London context, the overall lack of stakeholders required appropriate responses to mitigate the situation. To engage grassroots organisations and residents, an extensive phase of raising awareness, building trust and even social group formation was deemed necessary. More investment in time and human resources in the earlier stages of engagement were allocated to support the building of social and governance networks in a context where there was a thin foundation to start with.

Pre-Phase Synthesis Strategies

Know your community: work to understand the make-up of your local community. This helps ensure that you are capturing the full range of lived experiences.

Put co-creation at the core: incorporate the co-creation process as business as usual for engagement with local stakeholders.

3.2. Phase 1: Communicating and Including Stakeholders in the Process

This extended process of raising awareness, building trust and supporting social group formation began with a phase in which different strategies that involved reaching out and communicating with local stakeholders was highlighted. Many strategies in the initial phase are not focused on collecting data from the stakeholders but rather creating a positive context for the exchange of ideas and establishing relationships. The CLEVER Cities project did provide the time for such interactions to occur, but this may not be the case in many shorter projects. However, it can be critical to deal with issues of consultation fatigue, apathy and distrust that have become established in the community over time. If such issues are not addressed, effective co-creation may simply not be possible. The Thamesmead context proved an important testing ground for addressing these issues, and a range of strategies were identified to help in this process of transformation.

Beyond the process of identifying and mapping stakeholders, in the challenging engagement context of Thamesmead, the co-creation team endeavoured to connect with the community by first raising awareness of our work and establishing relationships with people. This often involved simply participating in existing events like markets and meetings and joining activities promoted by Peabody and other local groups that were ongoing and not necessarily directly related to CLEVER Cities’ goals. At these initial events, the non-local team members became more familiar to residents, and they could informally let people know about the CLEVER Programme’s goals and objectives. Becoming a constant and well-known presence at local events was an important beginning. Any meetings, workshops or focus groups that were being promoted for any reason became an opportunity to start to build relationships and consolidate the stakeholder mapping process. These relationships would become an essential component for the success of the project.

Communication began in these first events by raising awareness and opening two-way channels. By the end of the first year of activities, there were 175 people signed up to receive information, mostly local residents but also including some representatives from private and public sectors. The process gradually allowed information to reach the co-creation team and for some wider validation to occur.

As a step up from a communication-focused approach, there were actions that involved supporting small groups in their own endeavours. Being present to lend a hand and offering support with events not only led to stronger local organisations but also started to build relationships and provided further opportunities to call on these people as stakeholders in activities that were CLEVER related. Supporting local social groups eventually led to over 25 social groups being part of the co-creation process.

Another strategy, which was only partially implemented in Thamesmead, was the involvement of stakeholders from the outset of the project. Being funded by the EU and the fact that London’s UIP evolved over time, it was challenging to bring community stakeholders into discussions very early in the process. The UIP formation included a phase in which most stakeholders were from organisations and programme partners. The initial version of the Theory of Change for the regeneration progressed with little grassroots participation or a process of validation. However, grassroots stakeholders were slowly coming onboard, and channels were developed for them to express their priorities. The discussions of goals and objectives with the community was realised in a less structured manner until some group formation processes matured. This did not impede the resolutions of many of the issues overall, but it did limit, to some degree, the depth at which community input structured the framing of the questions, which can impact people’s sense of ownership.

The process of building relationships culminated in the creation of the Community Design Collective (CDC), which represented the most in-depth channel of co-creation. It became the most active component of a new co-governance structure that would follow the project through to its implementation phase and beyond.

There is room for earlier involvement of stakeholders, but it will often be constrained by issues of apathy and distrust. Nevertheless, the strategy of embedding locals into the framing and stakeholder mapping is essential and should occur as early as possible. This will help begin the process of capturing real community needs and priorities, while beginning to overcome negative past experiences and establish positive relationships.

During initial phases, efforts were made

to create an environment where people felt at ease. Though this may seem obvious, it required planning and effort to create a welcoming atmosphere of acceptance and openness. This process could be improved significantly, and lessons learnt from this process include offering inviting and neutral environments with the natural elements that make meetings friendlier including food, drink, comfortable seating and avoiding overly formal language and procedures, see more [

46].

Some of the events held in CLEVER London had informal workshop-type atmospheres such as:

With the increasing importance of working online, it was helpful to consider the balance of face-to-face interactions with online sessions, as these became possible post-COVID. Giving some preference to face-to-face encounters made the process generally friendlier, as many participants reflected on the missing sense of connection in online meetings. A range of activities were utilised in these earlier phases of co-creation that were fun and celebratory in nature and where data collection was not the only objective of the encounter.

A critical component of reaching people in the community was to demonstrate that all perspectives were welcome. To overcome apathy and distrust, local stakeholders’ lived experiences needed to play a critical role in the process. CLEVER London endeavoured to create partnerships that represented a full range of experiences in a community. This was most clearly expressed in the Community Design Collective (CDC), which had people representing a diversity of life perspectives that were valued and important for the design process.

The CDC was a key part of another important strategy utilised in a context that was not strongly organised into social groups: supporting community building. In the Thamesmead context, this was taken to be a process of social group formation and an important response to the fact that there were few stakeholder groups to form the foundation for collaborative governance.

The gradual process of building relationships and offering support eventually advanced to supporting the formation of both social groups and online networks, both connected to and independent of Peabody as the principal administrative entity in the region. There were several stakeholders who had been involved in regeneration processes undertaken by Peabody in the years prior, and building upon these contacts was valuable. Direct support from Peabody in groups like the Culture Forum was valid and useful but it was important to increase the diversity of pathways through which residents could participate. To this end, there was an increase in the number of social groups of at least 60% over the period of the project (not all able to be directly linked to project actions), and this has laid the foundation for the ongoing work with horizontally structured governance networks ever since.

During this period, some social groups were aided in their formation and several other groups emerged organically. It is difficult to tell if these latter groups reflected any indirect influence of the programmes that were underway, but it is important to note that, during the first half of the project period, several social groups formed, including:

These are examples of new social groups in South Thamesmead that became important contributors to the co-creation process.

Along with these groups, there were other people who were brought into the development process via online and paper communications by following the Making Space for Nature (MSFN) programme (MSFN is, in effect, the local name for the CLEVER Cities Programme). Digital and paper newsletters and loosely associated Facebook groups all contributed to forming a network of stakeholders. As time progressed, groups emerged and consolidated, and will hopefully continue to do so. This diversity allowed for many different interests and goals to be expressed. It was important that people found their most comfortable means of expression that helped capture ideas and opinions from all parts of society and that led to increasing richness in the pathways to collaborative decision making.

Phase 1 Synthesis Strategies

1. Communicating and establishing relationships: prioritise establishing relationships by supporting local groups, being present to lend a hand and be part of existing events and encounters. These relationships and social connections form trust over time. When possible, do not rush to apply methods to extract information.

2. Involve the community throughout and from the outset: involve the community from the earliest opportunity, ideally from the agenda-setting stage. Design/deliver a multi-stage iterative process that is flexible enough to respond agilely to emerging needs.

3. Create a welcoming atmosphere: work to create a welcoming atmosphere of acceptance and openness for all types of engagement. Offer inviting and neutral environments together with warm greetings, food, drink and comfortable seating, and avoid overly formal events. Consider the balance of face-to-face interaction with any online engagement and give preference to face-to-face, friendly environments when possible [

47]. Develop activities that are both productive and enjoyable to take part in [

46].

4. Work towards diversity of perspective: demonstrate to participants that a representative diversity of perspectives is valued and important for the process. Lived experience plays a critical role in the process. Therefore, create partnerships that represent a full range of experiences in a community.

5. Support community building: help local stakeholders to form stronger and more cohesive networks. These groups might form around interests and/or representing larger communities. Let people know that you are open and able to help people with their collective goals and can help more informal social groups become more structured, empowered and connected.

3.3. Phase 2: Building Trust in the Local Community

Emerging from the process of group formation and once a critical mass of stakeholders had been included in the process, both CLEVER Cities and Peabody were anxious to test and innovate with new types of governance structures. This next phase of the process of building trust began to employ different strategies during the initial engagements. This involved discussing the CLEVER Cities programme objectives more openly and starting some of the earliest activities that included some form of data collection. Many strategies in this phase were about how to hold engagement events and activities in a manner that demonstrated that the co-creation team valued the lived experiences and observations of stakeholders but also by managing expectations by being open and transparent about the process. It was important to keep applying the strategies from the first phase and begin to consolidate the sense of the stakeholders’ contributions having an effective impact. This was quite possible for those who became part of the deeper, more intense multiple sessions and partnerships (such as the Nature Forum and the CDC) but more challenging with wider, less frequent, engagement that spoke to the community as a whole.

Though both deep and wide engagement are necessary, the more you require multiple, systemic inputs from the community, the more it is important

to work in smaller groups that can communicate intensely and build working relationships and trust that they can impact the process. Smaller groups helped people share and learn, and generally feel listened to [

46]. Also, it was important to set aside enough time for these groups to gain a sense of cohesion and purpose. With wider forms of engagement, where the goal was to try to reach significant portions of the community, it was still important to try to scale events such that they could be structured into smaller groups so people felt they could be heard. However, when less crucial design decisions were being considered, larger festival-type events were utilised to combine fun with raising awareness and collect some data.

The most effective deep engagement involved setting up a community-led design panel called the Community Design Collective (CDC). As the co-creation process unfolded and co-governance structures were being formed, discussions required groups who could work more horizontally and develop working relationships more capable of discussing detailed issues of design. Local stakeholders held important local knowledge, and this was best tapped into in these smaller working groups.

Thus, the goals of working toward more collaborative governance structures overlapped with strategies that considered group size and dynamics. For functional co-governance groups, limited size helped:

Ensure that people have been listened to so the designs that are created for the public realm reflected local needs and residents’ priorities.

Demonstrate a shift in Peabody’s way of working, increasing transparency in how all decisions are made and with that overcoming distrust (see next strategy below).

Devolve power and decision to the community groups that can work effectively and guide change.

Test co-governance models including the way the roles evolve and information is exchanged, as well as how cross-perspective collaboration occurs. (A deeper look at how these co-governance structures emerge and evolve can be found in [

17].)

The central partnership provided by the CDC helped create a strong working relationship, with open sharing of information and decision-making capacity, leading to strong levels of trust. The important decisions made by this group, their new understanding of the complexities of the regeneration process and their growing trust in the intentions of Peabody were eventually transmitted into the wider community. They became ambassadors for the collaborative governance process without losing their critical voices.

Communications were a central aspect of both initial and later stages of the co-creation process. As the partners became more integrated, more channels to disseminate information were developed. The systemic nature of these seemed to be the key to supporting transparency. The process of sharing information and collecting data from the broader public involved the creation of a range of channels that each reached out to different types of stakeholders. These channels were tested in order to support an ongoing exchange between stakeholders and the co-creation team.

Thus, working groups and the wider community were more involved in the process by making project information accessible and the decision-making processes more transparent. It was important to work towards everyone having a general understanding of the root issues. Transparency was consolidated by providing full access to project parameters, working documents and designs to both the CDC and to the wider community through an online portal. The creation of digital channels for participation was an important step in this process by facilitating the process of gathering ideas from all stakeholders, including technical and other institutional stakeholders.

The engagement practices in the CLEVER Cities project needed to communicate the opportunities and challenges of the proposed NbS projects effectively. On the one hand, this involved

managing expectations by not overpromising the scale of positive impacts of NbS, and, on the other hand, not letting apathy and disbelief in positive change dominate by

demonstrating effective change. In London, efforts were made to let people know what they could expect from the process and what was expected from them. This was especially true with the CDC, though the process could always improve and some confusion as to people’s roles did occur at the start. To demonstrate that not all difficulties were insurmountable barriers, smaller demonstration projects like the Tiny Forest and the Making Space for Nature Community Grants (see

https://clever-guidance.clevercities.eu/making-space-nature-grant-programme (accessed on 9 December 2023)) were able to show incremental change that would gain critical mass with each new addition.

As to be expected, there were many specific barriers to participation that were encountered and impacted, one way or another, the engagement process and the building of the co-governance structures. These barriers could have hampered significant trust in the process as they could be readily interpreted as forms of implicit exclusion. In the London living lab, removing barriers to participation was a priority. Many barriers were identified and addressed but some remained in place and became lessons learned that needed to be dealt with better in the future. Issues included people having limited time and resources to participate, questions of mobility and access to venues, worries about childcare, lack of translation services and others.

To capture a diversity of voices in South Thamesmead, as many challenges as possible were addressed by identifying enabling factors and applying them. Some of the principal actions were to:

Invite as many voices as possible into the development process;

Provide well-located meeting points;

Support with transport;

Provide financial support when possible;

Choose child-friendly venues;

Take care in choosing meeting times.

Some enabling techniques that were identified but were not fully put into practice included:

These latter examples serve as lessons for improvement in the future. It is important to work towards co-creation and co-governance processes that continually reduce the number and scale of the barriers to participation.

Related to the notion of effective change mentioned above was the strategy of identifying areas in which co-creation processes could produce quick wins that showed work being accomplished and improvements being made. Co-creation events that demonstrated progress were very successful in terms of attendance and participation. This indicated that there was some latent demand for residents to be included in the regeneration if the means for such participation reflected their capacities and motivations. Identifying some quick wins to celebrate and set up periodic milestones that could be celebrated collectively was helpful in creating a sense of accomplishment and overcoming apathy. Some examples of this included:

Foraging and jam-making sessions;

Contributing to the Thamesmead Festival;

The Maran Way barbeque;

Women’s Lounge workshops and events;

Edible Garden inauguration.

This was a means of healing the past sense of inaction by showing constant progress in resolving local issues or improving the quality of life. The anticipating of co-implementation phases such as the construction of the Edible Garden was extremely successful but organisationally taxing. Simpler engagement events like the no-mow design day were also extremely successful but with slightly less investment needed. Despite the challenges, increasing the range of such activities was a powerful way to alter perceptions in the community.

Phase 2 Synthesis Strategies

6. Work in smaller, effective groups: in conjunction with wide-ranging engagement, set up smaller working groups in which people can feel more comfortable, establish social connections and contribute more effectively to the solutions. Smaller groups help people share and learn, and generally feel listened to. Set aside enough time for these groups to gain a sense of cohesion and purpose.

7. Work transparently: make project information accessible and decision-making processes transparent. Discuss how communications can be set up to be systemic and focused. Work towards everyone having a general understanding of the root issues. Consider the diversity and range of communications and make sure stakeholder contributions are followed up by later feedback.

8. Manage expectations while demonstrating effectiveness: let people know what they can expect from the process and what is expected from them. Demonstrate that not all difficulties are insurmountable barriers and that there are both challenges and opportunities.

9. Remove barriers: consider how both small and large resistances to participation can add to the sense that extensive participation is not the desired end of powerholders. Identify and systematically remove as many barriers as possible to wide and inclusive participation of both co-creation and co-governance. Consider people’s limitations and anxieties and help them focus on their strengths and experiences. Demonstrate an understanding of the specificities of the local cultures and the decision-making context so appropriate provisions can be made.

10. Overcome distrust and apathy with quick wins: heal past issues and problems by showing constant progress in resolving local issues. Focus on identifying some quick wins to celebrate and set up periodic milestones that can be celebrated collectively and give a sense of accomplishment.

3.4. Phase 3: Sustaining the Co-Creation Process

Building trust is, in fact, an ongoing process maintained by a positive and productive relationship with the community. In South Thamesmead, this was an evolutionary process. The initial meetings of stakeholders and project partners were dominated by technical and institutional partners. However, as successive meetings and engagement events advanced, grassroots channels and partners were identified and added, culminating in the creation of the Community Design Collective (CDC), which, together with the other project partners, established a strongly horizontal governance structure that consolidated further as the project progressed. The establishment of the CDC was perhaps the most fundamental action that demonstrated that mistakes of the past would not be repeated, and new avenues of collaborative governance would be explored going forward. This has not meant that reaching a wider range of residents has not continued to be a significant challenge, but it has created the foundation for a more consistent and solid relationship between administrators and community.

As the early phases of CLEVER Cities London transitioned into active stages of co-design, it was necessary to provide meaningful opportunities for people to contribute. Peabody had shown a willingness to share power and involve people in the highest levels of participation possible. Some local institutional rigidity naturally was still spread throughout the major organisations involved, but there was a willingness to challenge these issues constructively. This not only led to effective co-design sessions but also laid the groundwork for collaborative governance to emerge.

Again, the most important evidence of that positive change was the fact that the CDC had significant powers to effect change. Other than the overall budget, even the distribution of resources was discussed with the CDC. Together with the other project partners, value engineering was a collective process, and hard decisions were taken with the full involvement of these community representatives. Interestingly, CDC members admit that it took some time before they realised that they had meaningful power.

Residents were brought into the process not only as part of the CDC but also as community researchers, and many other stakeholders were able to contribute through their specific organisations and validate the designs as they went through different iterations. The project evolved, and other networks were connected into this central partnership. These channels allowed for effective participation but often with less direct impact on designs. Individuals with little time were able to give ideas, perhaps only on one or two occasions, through street-level events or the online portal. Other local stakeholder groups, like the YMCA, were involved in more intense sessions with the designers, either online or face-to-face, in which ideas and issues were discussed over the course of an afternoon. The COVID-19 pandemic effectively limited, for a significant period, the input of dispersed community contributions. Online channels were created to compensate but were never as effective as street festivals and active events. Overall, the final solutions were significantly directed by community input.

The benefits of having both light touch engagement channels open for the wider public and community representatives actively working as part of the core co-creation team were to include both general community wants and observations, which have the main steps in the decision-making process validated and confirmed by residents. This format allowed for effective contribution to the process and, through the social networks of those involved, had a perceptible countering effect on the previous sense of disbelief and apathy.

With more, extensive levels of community involvement in the co-creation process, it became more important to help people build capabilities and confidence in their active roles in the South Thamesmead projects. Coaching, session training, shared work activities and some mentoring were provided to the CDC and community researchers, while other new groups like the Nature Forum were provided with opportunities for people to learn from each other and from specialists in presentations and on walks. Giving people the tools and the confidence to effect change as well as adopt new roles was an important step. People discovered their capacity to conduct projects and become active partners, thus strengthening their positive outlook.

It is true that organising and supporting capacity building for a community-led design decision-making approach required a significant investment in time and resources. Nevertheless, the overall assessment is that the process of raising the overall set of capacities that a community collectively holds has led to a more widespread sense of optimism and confidence in local regeneration processes.

People sharing local experiences, suggestions and offering solutions should

have their time, effort and contributions to the co-creation process recognised and, when possible, compensated for. This recognition shows that their contributions are being valued as well as helping overcome difficulties and barriers to participation [

46,

48,

49]. This notion was put into practice in CLEVER London through both paid community work (the CDC, the community researchers) and other forms of recognition.

The London team experimented with a range of different forms recognising contributions and offering incentives to participants that fitted into the following categories:

Through impact on project;

Recognition, acknowledgments and credits;

Material and financial;

Access to skills and capacity building;

Social events.

Even though not all contributions became integrated into the final designs, as far as possible, it was a goal of the process to demonstrate how stakeholders impacted the overall set of solutions. Through access to process drawings, reviews and shout-outs, the CDC and other stakeholders gradually became aware of their significant impacts on the final scheme. This was accompanied by acknowledgments and credits on documents and the inclusion of a powerful presentation by CDC members at the final CLEVER Cities conference in Hamburg. It was more challenging to keep community-wide participants aware of their contributions, but feedback online in on-the-ground events was provided. This wider outreach should be improved in future iterations.

As mentioned above, both CDC members and community researchers received pay to recognise the significant demands on their time and to create a sense of equal professional participation with the other members of the core co-creation team. There were community specialists together with other urban designer, engineers, NbS specialists and others discussing solutions on a more level field. This also helped bring a more diverse set of people to the CDC, as young people, parents and others could make space for intense participation with some financial support.

The Youth Eco Development Council helped to provide a set of guidelines on how to recognise the participation of young people, providing a mix of incentives including social events, material support, access to skills and capacity building. Their suggestions included green skills, visits to new places, CV writing workshops and networking support, as well as shadowing and mentoring programmes. This demonstrates the creativity possible in recognising and incentivising those people who are willing to dedicate time to the betterment of their communities.

Phase 3 Synthesis Strategies

11. Provide meaningful opportunities to contribute: show a willingness to share power and involve people in the highest levels of participation possible. Demonstrate your awareness of any local institutional rigidity and the willingness to challenge these issues constructively. Create a working environment that allows for community input early and frequently.

12. Help build capabilities and confidence: provide opportunities for people to learn from each other and from the technical team. Give people the time to build confidence in doing things in a new way and adopting new roles. Mix coaching with experiential learning, shared work activities and mentoring. It is important that people can discover their capacity to effect change and become active partners.

13. Recognise contributions: people sharing local experiences, suggestions and offering solutions should have their time and effort recognised and, when possible, compensated for. This recognition shows that their contributions are being valued as well as helping overcome difficulties and barriers to participation [

46,

48,

49].

The distinct characteristics of a community should be reflected in the co-creation strategies employed. Not every community will require extensive work healing past disappointments, building trust, and establishing new transparent relationships as a groundwork for collaborative governance. CLEVER Cities London’s process, as in Milan and Hamburg, all adapted the initial guidance methodology to fit their contexts. The cities invariably required the use of general methodological steps that could allow for some comparisons to be made but a balance had to be established. The process of selecting different engagement strategies and methods was critical to the successes achieved. To this end, by considering not only the contextual factors like consultation fatigue and empathy but also the phase of engagement (analysis, identifying problems, ideation, etc.), the depth of engagement, the target stakeholders and the limiting factors allowed cities to find their unique pathway forward through the co-creation and co-governance processes.

4. Discussion

In this research, the authors take as an underlying principle that urban design, planning and management should have

co-creation and co-governance at the core of the new business as usual [

7,

13,

50]. By integrating co-creation pathways in planning and management practices in local authorities’ routines, we not only help ensure the successful implementation and maintenance of NbS in cities but also build the practical foundations for co-governance. It is critical for every urban green space project to develop their own unique co-creation pathway together with local communities, working together as close as possible, from the project conception phase. Considering the learnings and experiences from the South Thamesmead context, it is important to consider what recommendations can be made with respect to the synthesis and collective impact of applying multiple co-creation strategies focused on trust building. Though distinct when compared with the other front-runner CLEVER Cities, it is possible to bring the strategies together into topical clusters that can serve as recommendations for places with similar situations. A number of the strategies and recommendations might also be applied across a wider range of contexts and neighbourhood profiles.

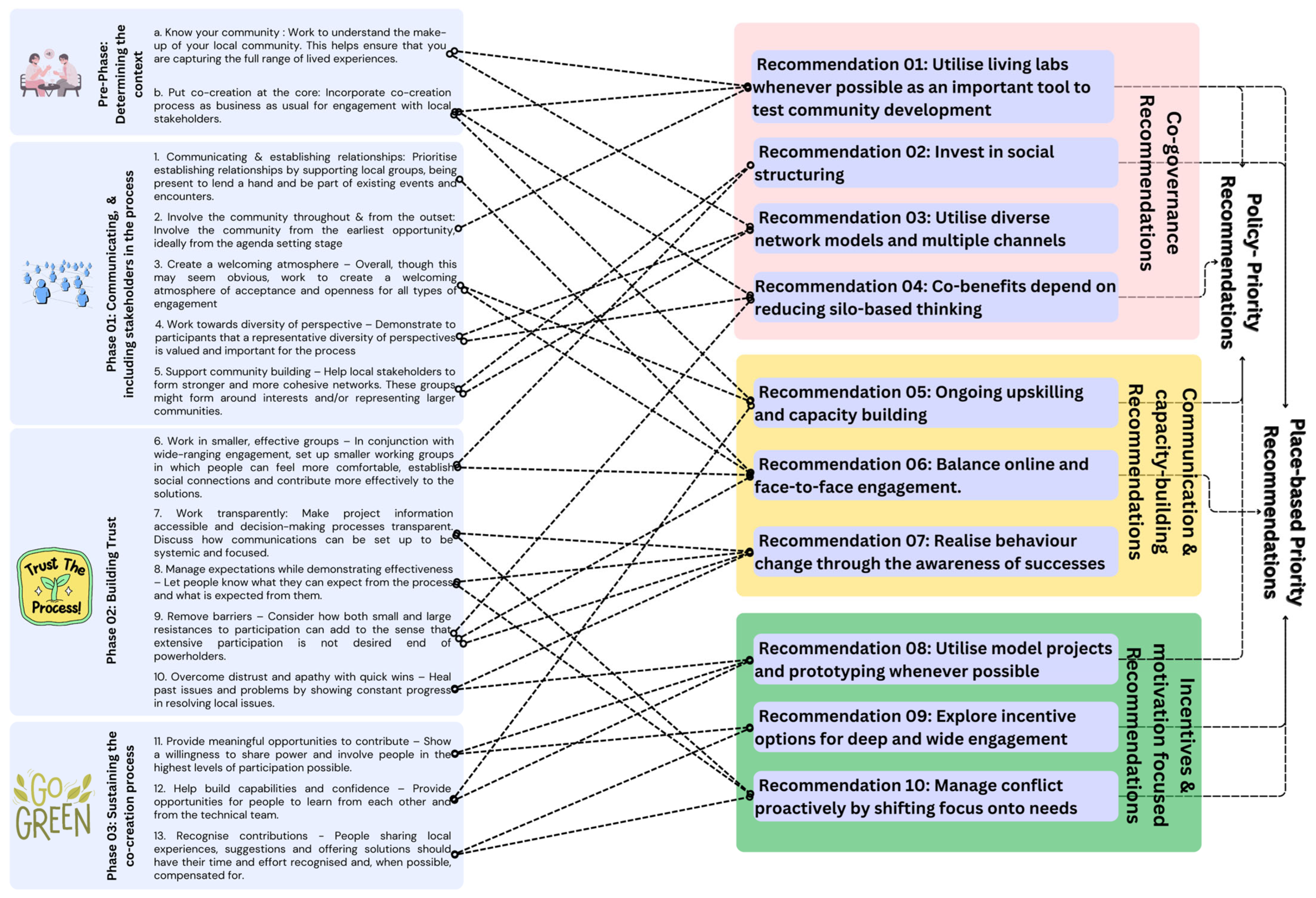

The specific learnings, challenges and opportunities encountered led to a set of recommendations that can be taken from the CLEVER Cities London experience. These are summarised in

Figure 3 below.

Some of the 10 recommendations are also highlighted as policy and place-based priorities, as this analysis can help inform future projects’ structure and order their co-creation approaches and prioritise actions. Therefore, these early-stage co-creation strategies not only help deal with issues of disbelief in top-down processes and distrust in regeneration projects, but they also help lay the foundations for collaborative governance, community capacity building and better motivational profiles that are critical to successful processes of change and management.

Recommendation 01: utilise living labs whenever possible as an important tool to test community development.

The use of living labs is becoming a critical tool for urban development. Co-creation needs to be practised, and both communities and government agencies need time to become used to new ways of working together. The living lab provides the space where this practice can occur and begin to inform larger and long-term co-governance structures [

13]. Living labs are places that can experiment with different solutions and with respect to both the processes of development as well as the solutions. Living labs should allow us to learn from both successes and failures, and help clients, communities and co-creation teams to establish what works on the ground. Trust is a necessary foundation for these stakeholders to work together in an open, exploratory environment.

Recommendation 02: invest in social structuring.

In contexts where there is limited existing social structure, it is necessary to help groups come together simply for co-creation to happen. There typically needs to be both deep and wide engagement and, for those types of engagement with a high demand for time and upskilling, it is not often feasible on an individual basis across urban communities. Beyond that, it is important to invest the time and resources into social group formation for several reasons including:

It is a foundation for collective community action.

There is an increased sense of belonging and social support and less isolation.

It can form an important component of information exchange.

It contributes to local resilience based on sharing and planning networks

In Thamesmead, the local stakeholder networks are still in the process of developing, evolving and consolidating, but there was a marked increase in the number of organisations and groups present during the time CLEVER was present. Social group formation and development is clearly supported by trust-building strategies, and a highly organised, networked community is going to be an important part of Thamesmead’s future.

Recommendation 03: utilise diverse network models and multiple channels.

Co-governance structures can be complex. In the London model, there was delegated responsibility to create a relatively horizontal governance structure that evolved and changed over time to include multiple semi-independent networks with significant levels of community participation [

17]. For such networking and horizontal integration to occur, solid levels of trust are important. Social groups need to have internal cohesion based on trust, as do intra-network connections.

However, the success of a group like the CDC does not mean, on its own, that there will be enough reach into the community. Other wider-ranging consultation information is essential to creating a sense of ownership in the community. Therefore, the creation of multiple pathways for contributions allows for informal groups and occasional participants to bring local knowledge to the table. The multichannel methodology (see

Figure 3) helps to collect information and spread decision making amongst a wider section of the residents.

Connecting the larger community to regeneration processes is dependent on these information pathways being credible and attuned to the local context and the distinct motivations and limitations of different stakeholder groups in the area. As new stakeholders are brought into the process, the quality of the relationships will determine the strength of the pathways with which information from the community is collected. The co-governance structures should be anchored in these networks and will depend on the information exchange they foster.

Recommendation 04: co-benefits depend on reducing silo-based thinking.

A critical lesson of NbS and systems approaches are that creating multiple co-benefits to every action and process is key. To this end, it is necessary to work to breakdown the silos and institutional resistances to collaborative processes like co-creation. When trying to produce and understand the co-benefits of project actions, different sectors and different voices need to be present. This involves not only an interdisciplinary approach but also an enhanced level of collaboration among institutions and departments in local authorities and citizens. These closer connections are dependent on the networks created in the early stages of co-creation and are critical to the overall success of NbS implementation [

16].

Recommendation 05: ongoing upskilling and capacity building.

Beyond the capabilities needed for stakeholders to be effective in specific types of engagement, it is generally positive to establish an ongoing process of increasing the pool of local people who have been exposed to training in topics related to urban design, planning and management. This can occur either through participation in groups like the CDC or via other training opportunities, including those needed to improve the participation process overall. Bringing in new UIP members is necessary and is helpful, as it also adds to the level of comfort and skills of stakeholders. In support of this, it is important to consolidate access for a diverse range of participants with especial focus on youths. Involving people in co-creation processes, at any level, raises their skill levels to some degree, with on-the-spot learning, experience and confidence building. Participation supports knowledge transfer in general.

Recommendation 06: balance online and face-to-face engagement.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the benefits of using online engagement were made apparent, and have come to be an intrinsic part of any communication process between administrators and communities. In CLEVER London, the use of online meetings allowed for more consistent participation rates and, together with the use of tools like MIRO Boards, community members felt they had the time to include detailed observations. Despite more face-to-face contact being possible, it would seem best to continue to experiment with the use of both digital and analogue engagement, until a balance of efficiency and a solid sense of collaboration is found. It is important to include time for social interaction between social groups, as trust building depends on relationships that can be limited by only digital contact. Furthermore, sponsoring some face-to-face events for UIP members allows them to act as ambassadors and networkers and combat myths and disinformation about administrative processes.

Recommendation 07: realise behaviour change through the awareness of successes.

The underlying goal of any management process is to achieve positive behaviour change in the community in question. A critical component of this is the effect information has on people. It is through the internalisation of information that people effect change on themselves and/or their surroundings. Thus, the transparency that is critical to building trust is also critical to deliver more consistent and widespread behaviour change. In particular, having positive models and success stories celebrated, not only has a strong impact on building trust in the system but also helps change people’s behaviours. The CLEVER living lab co-creative processes have proven to be a solid model for going forward because they include demonstration and practical application combined with hands-on learning and research.

Recommendation 08: utilise model projects and prototyping whenever possible.

The success and the function of the early-stage co-implementation cannot be understated. There are several benefits that arise from creating opportunities to stagger implementation, despite the administrative difficulties this presents. To most residents, seeing is believing, and when the process allows for small demonstration areas to be built, it brings people forward who are not reachable by paper or digital media, and it provides a canvas for community leaders to start to create new networks early in the process. In general, seeing implemented solutions helps to overcome many negative narratives that have gained credence over time. The community grants programme was an effective process in setting up what amounted to numerous prototypes all over the region.

Recommendation 09: explore incentive options for deep and wide engagement.

There are different ways that people are motivated. This includes being intrinsically motived by interest in the subject, integrating project goals into one’s core values or identification with those goals [

51]. Of course, there is also the motivation that comes from self-perception and recognition by others as well as from material and financial benefits. These can all be important parts of the motivational framework. The stakeholders who opt to be deeply involved and invest significant amounts of time typically have different motivational frameworks from those at the other end of the spectrum who drop-in from the wider community for one or two engagement events. Understanding, characterising and mapping these differences can be critical not just to involve people in an engagement event, but also to keep them involved over time and move towards the creation of co-governance structures.

To this end, a wide array of incentives can be developed to maintain the participation stakeholders. As was discussed by one of London’s youth groups, many different social events, access to skills, tours and visits and even mentoring programmes can be considered effective incentives. Direct pay was considered by both the members of the CDC and the administrators as an integral part of the success of the programme, so this must be considered as well. There are many ways to incentivise people over time, and this should be considered within a systemic and long-term context.

Recommendation 10: manage conflict proactively by shifting focus onto needs.

Breakdowns in trust are always a possibility and these may lead to conflicts within networks, and between stakeholders and even organisations. To re-establish trust in the process, it can be helpful to utilise several of the co-creation strategies identified in this research. First, discuss the importance of maintaining positive relationships over time. Then, making sure the process is transparent and recognising the contributions to the process can also help significantly. As conflict emerges, it can be managed proactively by separating the people from the problem and reaffirming the collective importance of increasing the measurable goals associated with well-being and flourishing. Both human and non-human stakeholders have needs that can be maximised. By focusing on the problem of maximising need satisfaction through co-benefits, it is possible to move away from rigid negotiating positions [

52]. If this can be presented as a common problem, not a negotiation, and expectations can be set to achievable levels and aligned with available resources, time and capabilities, solutions are possible. Lastly, when discussions on how the maximising process can be measured more objectively, then there is a chance to deal with issues before they escalate.

The set of recommendations presented here is not exhaustive and they are born of co-creation strategies that reflect the specific context in which limited social structuring has taken place and levels of trust are low. Nevertheless, the synthetic and more general nature of the recommendations make them more widely applicable than the set of individual strategies. The recommendations that support co-governance are, in fact, widely applicable. Still, the co-creation process is always context dependent, and these recommendations must all be considered in that light.

5. Conclusions

The balance between local context and the unifying influences that come from a large project framework like CLEVER Cities underlies this study. The three phases described in the results section are integrated into the CLEVER Cities co-creation, but they precede the main co-design sections applied in the other cities and they detail the specific response of the London team. Top-down directives and guidelines led to parallel processes in each city that would end up converging at multiple points as the process developed. For example, in the initial phases of the project, technical and institutional stakeholders were involved in the framing of the project while grassroots stakeholders were already involved in identifying local issues. This was in part due to the slow build-up of local stakeholders but also a consequence of the organisational structure that comes with external financing. Within this context of local versus international influences, London CLEVER Cities could not ignore the very specific challenge of limited social structuring, and a history of perceived abandonment and the resulting distrust of many residents. The recommendations are, therefore, partially a reflection of the CLEVER Cities framework and partly reflective of the challenging context found in South Thamesmead.

The challenges encountered, such as the impacts of COVID-19, did lead to some of the more important lessons. Despite a difficult context for the initial engagement, by establishing new and strengthening existing stakeholder networks, it was possible to build up a critical mass of networks to create significant success with co-creation. The results of supporting and building new social networks during the early stages of the co-creation process will continue to evolve and adapt over time, leaving a new baseline for future projects in the area.

While it might not be possible to use all these strategies in every project, each helped to bring the co-creation team together and reduced initial community reluctance to trust the process. With time, it may be possible to achieve a level of acceptance that lets the community assess new projects based less on preconceived ideas and past issues. Considering a history of relatively superficial consultations and projects that faltered before implementation, understanding and addressing past experiences was imperative. By taking the time to comprehend the local culture of participation, rectify previous errors, and cultivate genuine relationships of trust with the community, the CLEVER Cities project has helped change the general atmosphere in Thamesmead, at least to some recognisable degree.

In summary, the extensive social structuring and trust-building phase was essential to the London context and was a key aspect of the process. This commitment to developing a bespoke approach to the Thamesmead context is the critical takeaway for others involved in the development of a co-creation process.