1. Introduction

The planning and provision of public transit systems is a complex and contentious process that is governed through a variety of overlapping strategies and actors. In recent years, new trends including the rise of Technology Network Companies (TNCs), localized financing and global pandemics have made apparent the limits of existing governance systems. As public transit agencies struggle to adjust to changing circumstances and new competition, the strategies available to them are shaped considerably by the formal governance structures that guide decision-making processes, define responsibilities and shape organizational capacity. To date, however, scholarship on public transit has primarily focused on the technical and operational factors rather than the decision-making processes that support, hinder and shape implementation of these factors. One of the major constraints on research is the lack of information about the formal decision-making structures of transit provider organizations. While the United States’ National Transit Database (NTD) and the American Public Transit Associations’ Vehicle and Infrastructure databases provide annual information on fleet types, service characteristics, system performance, ridership, and expenses, these databases have little information about the decision-making structures of the organizations profiled. This lack of information shapes current research by limiting our ability to comprehensively analyze the impact of formal organizational structures on observed practices and outcomes, essentially rendering formal governance as an invisible variable in the study of public transit planning and policy implementation.

In the paper that follows, we discuss the development of a novel governance-oriented database for U.S. transit, analyze general trends across the 68 providers in the database and propose new research questions to support governance-oriented research agenda for the field of urban transit planning. Governance of public transit is a complex process that includes formal organizations, informal and professional networks, discourses, norms and a variety of institutional factors, mobilized to achieve an agreed upon goal [

1,

2,

3]. The examination of how organizational structures influenced decision making has been undertaken in other fields more than in transit planning. As existing scholarship indicates an important role of governance, i.e., financing, discourses, power and other institutional characteristics, in urban transit processes and outcomes, governance should be included as an explanatory variables in the study of urban transit. Our analysis of public transit governance in the United States begins with an examination of the formal structures of decision making, but recognizes that this is only a single aspect of governance. In this paper we demonstrate the variation in formal governance structures across U.S. transit providers, and identify correlations with specific modes and geographic locations to support further inquiry into the relationship between formal structures and observed outcomes.

1.1. State of the Research: What vs. How

A strength of urban planning is its interdisciplinarity and comprehensiveness as a field of scholarship, but research subcultures within planning (such as transportation) vary considerably in their embrace of diverse methodologies and acceptable lines of inquiry [

4]. Scholarship on urban transport is dominated by technical “What” questions [

5,

6], such as “What technologies and policies best achieve the stated goals?”; “What is the relationship between urban transport and land use, spatial equity, private investment patterns?”; or “What are the most effective financing strategies for incentivizing changes to travel behavior?” Inquiry into these important, policy-relevant questions favors quantitative analyses based in frameworks derived from engineering and economics [

7]. In the United States in particular, research funding that emphases engineering fields and applied solutions reinforce the dominance of such approaches to urban transport scholarship [

8]. Yet these “What” questions offer an incomplete view of how policy is crafted.

There is an emerging recognition about the need to expand the focus of transport scholarship [

2,

5,

8,

9] to include more “How” and “Why” questions and inquiry into the policy creation and implementation process. By focusing primarily on ‘what’ questions and technical issues, current transport scholarship fails to engage important practice-related issues related to context, power, and resources [

8], leaving us with a science of applied policy making that exhibits considerable distance from the realities faced by practitioners and, thus, is less likely to make substantive improvements to practice [

5]. Existing scholarship suggests that the impediments to sustainable transport are institutional, not technical; the primary bottleneck in our pursuit of sustainable transport is the decision to adopt, deploy or use a particular technology or policy tool [

1,

3]. While technical and operational barriers exist, most are well understood and involve fairly routine actions for implementation; decisions to do things differently, i.e., employ alternative or emerging solutions such as new infrastructure investment, road-space allocation, and system pricing, is challenged by existing institutional landscapes and established governance systems [

9,

10,

11].

Recent scholarship highlights some key deficits in our knowledge about transport governance. In their review of contemporary scholarship on governance of transport, Marsden and Reardon [

5] found that only 13% of research papers from two leading transportation policy journals consider specific aspects of the policy process and that two-third of papers did not engage with real-world policy examples or policy makers but focused on quantitative analysis alone. Focusing on the U.S. context, Lowe [

8] identifies a substantial gap in competitive National Science Foundation research funding for urban transportation between the engineering and computer systems directorates (75 awards in 2017) versus the social, behavioral and economics directorates (7 awards in 2017), further illustrating the technical orientation of the field.

Scholarship on how governance influences transport planning processes and policy outcomes, albeit relatively thin, highlights financing, discourses, power and other institutional characteristics as key factors influencing policy formation and implementation. Flyvbjerg’s analysis of sustainable transport plans in Aalborg, Denmark [

12] and his work on megaproject planning and financing projections [

13,

14] illustrates the central role that power plays in transport policy formation and implementation. Marsden and May’s [

10] analysis of local decision making in London and Edinburgh shows how the balkanized governance structures of urban transport impede the implementation of effective cost cutting measures and conclude that a regional tier of government could be more effective, if given the appropriate organizational capacity and funding support. Focusing on the Australian case, Legacy et al. [

15] conclude that organizational integration is not as important for policy cooperation as other institutional strategies such as strengthening stakeholder networks and enforcement of regulations by current organizations. Other studies have found no major differences between the two most common types of governance arrangements for public transit in the United States (i.e., general purpose and special purpose governments) and transit effectiveness and efficiency [

16,

17] or conclude that service area characteristics have a larger influence on transit spending and expansion than the form of governance employed [

18].

1.2. State of the Research: Governance and Scale

Much of the debate about transport governance in the U.S. context has centered on regional decision making and the work of Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs). Sciara [

19] provides an organizational history of MPOs since their creation by federal legislation in the 1960s while Sciara and Wachs [

20] identify various MPO financing strategies and discuss how organizational models may influence outcomes. Weinreich investigates the challenges of using local option transportation taxes [

21] in a regional context [

22,

23] identifying how formal organizational arrangements influence local financing outcomes. A recent analysis by Weinreich et al. [

24] expanded the MPO focus to include local government data to illustrate the fragmented nature of urban transit provision across 200 metropolitan areas in the United States. Weinreich et al.’s unit of analysis is the local government, rather than the transit agency, and as such, it provides an overview of fragmentation but less insight into the variations in formal transit governance. Examining MPO governance from an equity and justice perspective, Sanchez and Wolf [

25] find that governing boards are overwhelmingly white and male, while Lewis [

26] identifies a suburban bias in MPO decision-making structures and processes. All of these aspects are expected to influence the planning and policy guiding transit provision.

A focus on MPOs as the primary structure of transport governance is a result of federal policy that aims to place urban transit as a regional competency by establishing regional bodies for funding and comprehensive planning. The challenges facing public transit, however, are increasing decentralized and ineffectively addressed solely at the regional level. Local land use decisions and the need for local sources of funding impede the implementation of regional transit-oriented development [

11,

27] while privately-operated TNCs and other new mobility services eschew regional service provision and planning approaches for highly decentralized service models [

28]. New service models and providers have increased the relevance of city-level transport policy (as opposed to regional or federal). Some of these solutions are focused on reducing the need for transport rather than enhancing existing urban transit services, such as the 15/20/30 minute city [

29,

30]. Aided by the global pandemic, the 15 minute city is gaining traction as a means to help “cities to revive urban life safely and sustainably in the wake of COVID-19” by “reduce unnecessary travel across cities, provide more public space, inject life into local high streets, strengthen a sense of community, promote health and wellbeing, boost resilience to health and climate shocks, and improve cities’ sustainability and liveability” [

31] (page 1).

While contemporary events have efficiently highlighted the failure of our existing governance arrangements to deal with exogenous shocks, they also highlight the relative lack of knowledge about the governance structures and processes currently used to provide urban transit services in the United States. Recent experiences warrant several important questions for public transit. How do existing governance processes support the adoption of emerging solutions and policy concerns? How do governance structures that were established in previous periods, under different conditions, shape contemporary implementation? What governance reforms would provide more equitable and sustainable outcomes? Without a solid theoretical and empirical understanding of how transport governance currently works in the United States, urban transport scholars and policy makers are not well equipped to consider or adopt emerging paradigms and decentralized solutions in a comprehensive manner.

Research on the engagement of residents and system users in the transit planning process contributes to understanding of governance processes. Some of these studies use techniques such as multi-criteria decision analysis to assess how stakeholder preferences affect overall decision making for bundles of transit services, e.g., [

32,

33]. Stakeholders are assigned as government, designers, developers, communities and so on. These types of studies focus on decision-making processes about aspects of transit services that balance various preferences for social, environmental, and economic outcomes. These studies collectively provide deep understanding of stakeholder-oriented analysis. Where this research differs from these approaches is that we argue that governance affects transit outcomes as the structure, such as governing board composition, will influence preferences within stakeholders. Board activities, such as review and development of an organization’s mission, have been shown to affect transit priorities [

34].

In the paper that follows, we develop a typology for governance structures of public transit in the United States to support further inquiry into how organizational structures influence policy making processes, organizational capacity and policy outcomes. Rather than treating institutions and governance as background contexts for the investigation of policy making, we seek to make them the direct focus of inquiry [

35]. Our effort builds upon Hanson’s 2006 call for transportation scholars to “imagine questions, methodologies, and epistemologies beyond those bequeathed to us by economists and civil engineers” [

7] (page 232) and our desire to support improvements in the practice and processes of local transport planning in pursuit of just outcomes.

In the sections that follow we utilize a novel database on public transit governance to define a typology of formal governance of public transit in the United States. We first define our methodology, assumptions, and data sources we utilized to build the transit governance database. We then discuss the typology and describe how transit governance strategies align with different modes and geographies. In the final section we lay out research questions and suggest new inquiry themes for better understanding the decision-making processes and outcomes of public transit in the United States.

2. Methodology and Transit Governance Database

To develop a typology of formal governance of the operation of transit in the United States, we assembled a novel database on transit systems across the United States Using transit provider websites, existing scholarship, the U.S. Federal Transit Administration’s National Transit Database (NTD), and media articles, we assembled information about the organizational decision-making structures of 68 total transit agencies operating across 40 cities. Our unit of analysis is individual transit agencies, as defined by the NTD, as they are the entity responsible for the day-to-day decisions about transit provision. To specifically orient our analysis toward local governments and sub-regional actors, we selected only transit agencies headquartered within the most populous cities and excluded suburban-based transit systems. The NTD contains only those agencies that receive federal money, and excludes systems funded entirely from local sources (in the cities selected for this database, only the Las Vegas Monorail fits this criteria). Our database also excludes private companies that may receive federal money through a contract, namely two ferry companies and a vanpool service; these were excluded from the database because they do not align with our focus on public decision making. Lastly, we limit our database to agencies providing fixed-route service, which removes demand-response services such as paratransit. All transit agencies in the database are defined as full reporters to the NTD, meaning they operate at least 30 vehicles or operate a fixed guideway service (e.g., streetcar). Restricting to full reporters provides access to a richer variety of service data and does not meaningfully impact our database. For the modal categorizations, agencies that operate only bus-based modes (including commuter and rapid buses) are bus agencies, agencies that operate only rail (streetcar, heavy rail, light rail), commuter rail, or ferries are categorized respectively, and agencies that operate multiple modes are considered multi-modal.

To construct the database, we reviewed websites for all 68 transit agencies to gather information about their formal governance structures. Specifically, we checked whether the agency was governed by a board of directors or functioned as a department of a generalist governing entity (e.g., city, county, or state). If the agency had a board, we collected information on board composition, including the number of board members, the share of members appointed by the mayor or city council of the largest city, and the level of jurisdiction with majority control (city, county, state, or partnerships thereof). The last decision involved a considerable amount of discretion for some agencies as, recognizing the multi-scalar nature of transportation, they included county, state, and city officials on governing boards. In cases where the majority control was not immediately obvious, we defaulted to looking at how statutes appointed members or votes (e.g., x members must be from y county), such that the data may undercount the sway of some cities within their agencies.

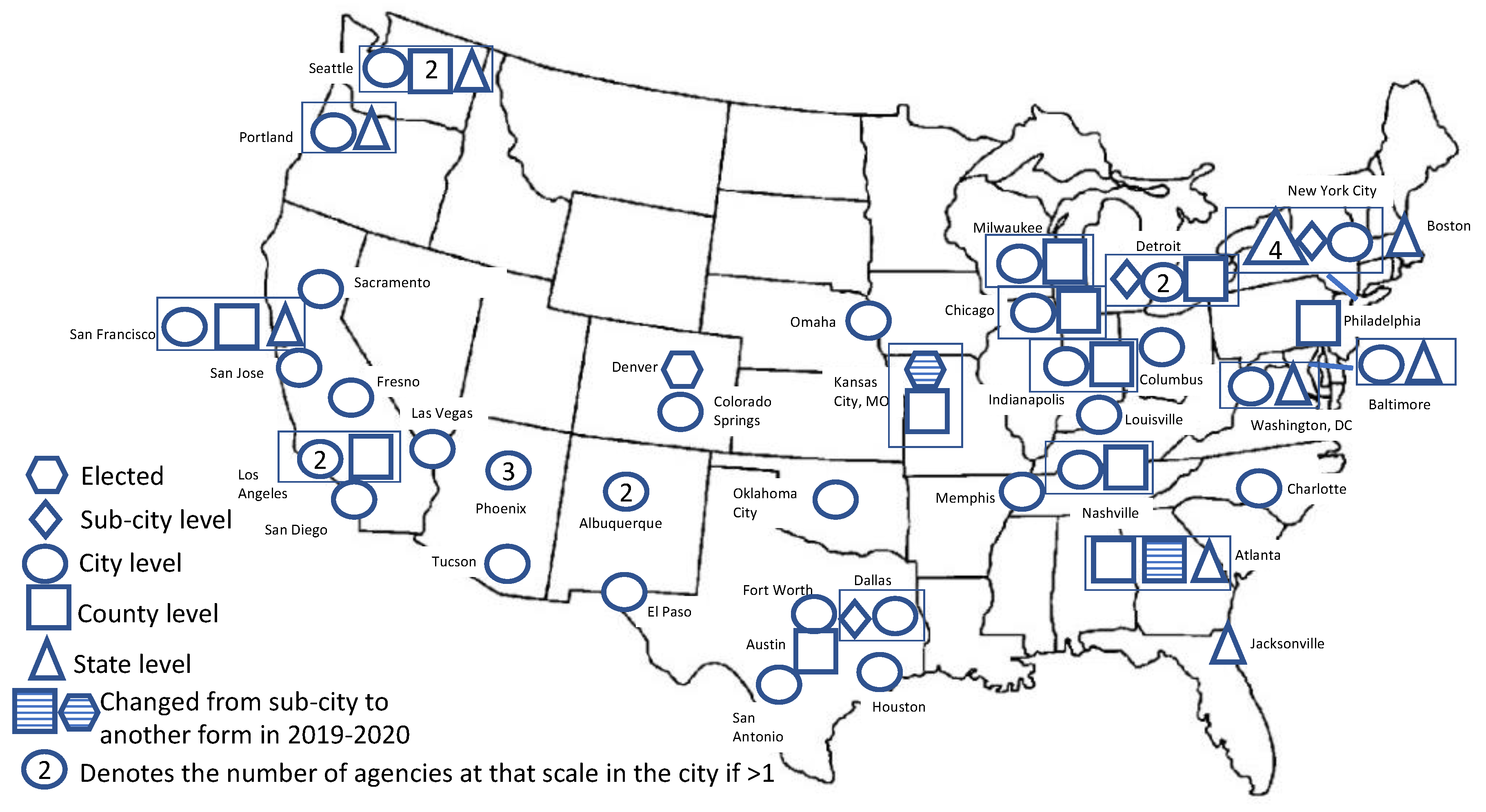

The map in

Figure 1 shows the selected agencies (

Figure 1 utilizes graphics to enhance visual accessibility), placed on their respective cities and symbolized by the geographic scale on which their board is composed. The number of agencies varies by city. New York City—the most populous urban area and the region with the highest level of transit mode share in the United States—has transit services provided by six separate agencies. The primary provider of transit services, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), is actually a composition of four agencies (one responsible for the subway and most buses, one for select outer borough bus service, and two for the Long Island and Metro North commuter rail systems). In addition to the MTA, there are two agencies that operate ferries: the city’s department of transportation, and the non-profit NYC Economic Development Corporation. In contrast to New York City, Mesa, Arizona, though one of the 40 most populous cities, is not shown on the map because its transit service, Valley Metro, is headquartered in neighboring Phoenix, the fifth largest city in the nation. The map illustrates the geographic variations in transit governance (discussed below), with a greater share of state and county led public authorities on the East Coast and more transit provided by cities or partnerships of local governments in the Western states. Another observation is that many cities have transit agencies operating at multiple geographic levels such as Seattle which has state-run ferries, a light rail and commuter rail system run by a county-level partnership, a county level bus system, and a city-ned monorail.

3. Typology of Public Transit Governance

Public transit agencies inhabit a unique class of government in the US. Transit is governed most frequently by single-purpose organizations whose responsibilities are often constrained to a single transit mode, or to a set geographic region that may not correspond with the regional transit shed. Historically, transit provision was provided by Quangos (quasi-governmental organizations; a term more commonly used in the UK than in the US) with substantial budget autonomy and minimal direct democratic oversight. Public authorities, a type of Quangos, are a popular governance structure for public transit in the United States; other common governance structures include regional or county-level collaborations organized as intergovernmental consortia, established departments within municipal governments, and (increasingly) sub-municipal or neighborhood level non-profit governance arrangements. In this section, we categorize the 64 transit agencies by their primary formal organizational structure to develop a typology of governance and illuminate the formal institutional structures that currently govern public transit. Our aim is not to draw clear conclusion about the influence of different governance structures on public transit outcomes, nor to provide a history of governance trends but rather to propose a typology for categorizing and analyzing the formal decision-making structures for public transit to support future research into the politics and institutions of public transit provision in the United States.

3.1. Transit Board of Directors

The majority (76%) of transit agencies have a board of directors as part of their governance structure (

Table 1). As plural-headed public bodies, the rules that govern board activities, composition and capacity vary considerably across context. Lacking a national model statute, state enabling statutes specify the selection methods, size, terms, composition, compensation and functions of public boards [

36]. In his analysis of a variety of public boards, Mitchell illustrates that board members are often nominated by a chief executive and approved by legislative bodies; include members that serve in an

ex officio capacity where their position places them automatically on boards related to their work (i.e., NJ Commissioner of Transportation is on several state transport boards) and that most boards are involved only with policy making, although some manage day to day activities. More broadly, reliance on boards of director governance reflects the experimental character of American public administration [

37,

38], as they are created for various reasons and offering varying approaches to governance. The variety of approaches can provide insight on both of the politics of governance/decision making and the formal institutional structures shaping transit service provision in different contexts.

Across the public transit agencies shown in

Table 1, board composition and size vary greatly, with Valley Metro Rail’s four-person board the smallest and Regional Transportation Authority (Nashville) the largest, at 36 members. Boards are also composed by stakeholders operating at different geographical scales. In the federalist system of the United States, national and state governments are given independent powers by the constitution while counties, regional entities and local governments are ‘creatures of the state’ and have only the powers and responsibilities delegated to them by state enabling legislation [

39]. Thus, the locus of control over public transit varies considerably across metropolitan areas and states. Of the 51 board-controlled agencies, 20% (10) have a board primarily controlled by the state, 22% (11) are controlled by a consortium of municipal governments, 22% (11) by county governments or municipal actors assigned by county, and 26% (13) by a single city. Three operate at the sub-municipal level, representing neighborhoods or urban areas that fall within but are not contiguous with municipal boundaries, and with boards intended to distribute control across levels of government. Until 2020, only one agency, Denver’s Regional Transit District, has an elected board of directors, but in 2018 Kansas City residents voted to create an elected board of directors for its streetcar board. In 2020, streetcar systems in Atlanta and Kansas City changed their governance structures, with Kansas City moving toward a directly elected board of directors and the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) fully took control of the Atlanta Streetcar. These changes are reflected as stripes in

Figure 1 and illustrate the difficulty of tracking transit governance over time.

3.2. Typology of Transport Governance for U.S. Systems

3.2.1. Public Authorities

Established in the mid-20th century as an organizational response to shifts in urban transit provision and changes to federal policy, regional public transit authorities are a common organizational vehicle for the development and implementation of transit.

Table 2 shows the variation in governance by level of control and transit mode in the United States. Through their ability to independently issue revenue bonds, and board-based decision making, the public authority model was intended to isolate policy decisions from political pressure by depoliticizing the decision-making process [

37]. In practice, however, public authority structures are easily captured by specific interests that may be at odds with desired policy outcomes. In particular, the board structure can strongly influence priorities and decision making as boards represent political boundaries, such as central cities and suburbs, rather than population, ridership or employment centers.

The public authority model is used by state, county, and local stakeholders, and features considerable variety in the management of public transit. State-charted public authorities include all of New York City’s Metropolitan Transit Authorities, Portland, Oregon’s Tri-Met and Jacksonville, Florida’s Transportation Authority. City-based public authorities are also commonly used to provide bus and rail services across the municipality, and even outside its jurisdiction, as with the CTA’s rail service to Evanston and Skokie, Illinois. Interesting, our analysis showed no public authorities constituted at the county level, with the caveats that certain municipalities in our database such as Indianapolis and Houston have borders that are largely contiguous with the county.

3.2.2. Intergovernmental Governance

Another trend in the formal governance of public transit is the intergovernmental approach (

Table 3). These governance arrangements are defined as collaborations between individual municipalities who can opt into public transit service but are not required to participate. A classic example is Valley Metro Bus and Valley Metro Rail serving the Phoenix, Arizona metropolitan region. Individual cities in the Phoenix region choose whether to become members of the Valley Metro system; services are primarily funded by each municipality with additional support from a regional sales tax, but operate under a unified brand. Municipal members appoint representatives to the Valley Metro board which oversees customer service, system management and long range planning. A similar governance arrangement is used in the Dallas Fort Worth region where the Dallas Area Rapid Transit System (DART) was created after 15 local municipalities voted to levy a 1% sales tax to create the system in the 1980s. Today, the organization is governed by a board of directors appointed by the mayors of member cities including 13 seats reserved for representatives from Dallas. An interesting outcome of these collaborative, intergovernmental approaches is that municipalities can also vote to withdraw from participation, as the suburbs of Coppell and Flower Mound did in the Dallas region, or opt-in to the growing system at later points in time, as occurred with the expansion of Seattle’s link rail to the suburb of Tacoma. In comparison to the public authority model, then, intergovernmental approaches to public transit provision introduce potentially more flexibility while vesting municipal leaders with direct authority over service provision and policies.

The intergovernmental approach to public transit provision is found through the United States, and across legacy and newer systems (i.e., Philadelphia, PA and Austin, TX). It appears to be a common strategy in growing metropolitan regions in the Sun Belt, including Phoenix, Dallas, and Las Vegas, but can also be found on the west coast (i.e., Seattle, Los Angeles) in the Midwest (Detroit and Kansas City). Intergovernmental arrangements are used for all modes, but are particularly common for buses and multi-modal systems. In most cases the decision-making power of this intergovernmental collaboration is concentrated at the sub-state level, which is not surprising given the reliance on municipal discretion to participate.

3.2.3. Government Department

A more recent trend, begun in the early 2000s, is city governments taking responsibility for the success of transit operations within their borders [

40]. Though few, if any, cities have taken direct control of transit operations from authorities, a growing number are making standalone transit plans, adding transit sections to larger transportation plans, taking ownership of new modes like streetcars, and entering into joint funding relationships with regional agencies to increase service. Cities are hiring transit planners to liaise with agencies and help with street redesign projects, including tactical transit efforts [

39]. City governments are also operating circulator bus systems in parallel to regional bus systems; examples in our database include DC, Baltimore, Los Angeles, and Phoenix. Such city involvement can bring a welcome increase in transit priority but may deepen inequalities within regions and disrupt regional planning efforts.

Table 4 shows these arrangements between departments, level of control and mode.

Some cities directly provide the only transit services available to their residents due to an absence of regional providers. Tucson, Arizona; Fresno, California; Colorado Springs, Colorado; Detroit, Michigan; and Albuquerque, New Mexico feature transit systems that are, unlike the circulator services discussed above, the only system in each city. The department model also operates in King County and Milwaukee County on the county level and at Washington State Ferries and the Maryland Transit Administration on the state level, with transit operations being subject to the oversight of elected officials charged with general responsibility rather than transit-specific oversight. In some cases, transit-specific oversight is provided by special committees. King County Metro, for example, had six such advisory committees listed on their website for various planning activities and modes. Transit within generally elected bodies can have benefits for integrated approaches to problem-solving, but can suffer from inattention if other problems are more pressing.

3.2.4. Sub-Municipal Governance

Our final category for public transit governance captures an emerging trend toward decision-making processes based at the neighborhood or sub-municipal level (

Table 5). Since the early 1990s, urban transport, including public transit, has been increasingly relying on decentralized forms of financing, including local option transportation taxes [

21] and value capture [

41]. This trend has coincided with an increased focus on the local economic development benefits of public transit, as illustrated by the Federal TIGER (Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery) and the popularity of modern streetcar projects [

42]. These forms of sub-municipal financing correlate with sub-municipal governance structures in the form of non-profit organizations and business improvement districts, representing a hyper-localized approach that contrasts with the decades long efforts to develop regional level structures that cross municipal boundaries.

Notably, the sub-municipal approach to public transit governance correlates highly with capital intensive modes, namely rail and ferries, and to date has not been used to expand buses or commuter systems. The systems in the sub-municipal category exhibit considerable flexibility and innovation in governance: Detroit’s Q-Line is a public–private partnership that emerged from a regional planning effort [

43], Kansas City’s board of directors recently transitioned from appointed to directly elected and the city-operated Atlanta streetcar was (contentiously) absorbed by the regional transit authority, MARTA, several years after starting operations. Both the McKinney Ave (M-line Trolley) in Dallas and the KC Streetcar operate without a fare, using subsidies from the local municipality and localized land-based financing to cover the costs of operations.

4. Discussion

The decision-making processes of public transit organizations produce a wide range of strategies and solutions that reflect local context. The implementation of policy solutions is enabled or hindered by institutional structures at multiple geographic levels, ranging from sub-municipal to regional. To date, the small but robust scholarship on transit governance in the United States has focused primarily on metropolitan or regional governance through analysis of the form, scope and behaviors of federally mandated Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs). Recent trends in public transit toward decentralized financing and planning demand a broader geographical perspective that capture innovations and emerging strategies being used by municipal stakeholders outside the regional structure. The typology provided above aims to expand inquiry about transit governance beyond the regional and MPO focus to better align scholarship with these emerging trends.

A regional approach to understanding transit governance, while important, obscures the variety of governance models and emerging strategies being leveraged by public transit agencies, advocates and municipal officials at multiple geographic scales. The devolution or decentralization of transit financing and decision making to sub-regional and even sub-municipal levels suggests the need for a new framework and new data sources to think about transit governance in the United States. Decentralized approaches to transit governance introduce new priorities, values and metrics including new definitions as to what counts as a successful transit project [

43,

44] and we miss important lessons about the politics of public transit and policy implementation by focusing primarily on technical questions about operations and regional scales of governance. Rather than impose normative views about the appropriate level of decision making across all contexts, the typology described in this paper aims to support inquiry into the decision-making behavior of local and regional stakeholders to better understand the politics of goal setting, policy adoption and implementation strategies in public transit.

Two examples are illustrative. Like many public transit agencies, New York’s MTA is governed by a board of directors composed of both city and suburban representatives. Tensions between city and suburban transit funding influence decision-making and financing outcomes in ways that cannot be understood purely by examining the regional Metropolitan Planning Organization. A second example is found in the Kansas City and McKinney Ave streetcar systems which, in 2019, ranked as some of the most efficient transit systems (in terms of operating expenses / ridership) in the United States. Although neither line serves commuters, has a large daily ridership, or charges a fare, these sub-municipal investments have effectively leveraged land-based financing to achieve relative efficiency and effectiveness, albeit for a small geographic region. These local innovations—that aim to integrate transit and land use—challenge the notion that good transit is only regional and illustrate how public transit is increasingly marked by complex sets of overlapping priorities and institutional barriers to action. While transit agency behavior may look irrational from the outside, an understanding of the local politics of transit decision making provides insight on how to best augment existing decision-making process to achieve different outcomes, while also providing insight into how power exerts itself in the planning and project implementation process. Thus, in the 21st century urban transport is a multi-scalar concern that demands both coordinated regional action and localized, contextual strategies, as well as everything in between. Such trends warrant an explicit conversation about the scale of transport interventions and their effectiveness at addressing multiple needs and problems. In the context of urban transit, this also necessitates a consideration of how governance structures can be augmented to perform efficiently, and equitably at different scales. Scholars of urban transport are ill prepared to take up this charge, as governance and organizational structure are largely unobserved variables. This limits our ability to analyze and unpack decision-making processes, including identifying the goals that are important to decision-makers and how existing structures shape their efforts to achieve these goals. Understanding the decision-making process, power and the role of context is increasingly important for understanding how best to achieve equitable and effective policy solutions in this era of globalization and technological change.

5. Conclusions

The public transit governance typology outlined above illustrates the substantial variation in transit governance across and within cities. As transit finance has decentralized, local and sub-local forms of decision making have become more prevalent but, as the database presented illustrates, localized efforts tend to be confined to specific modes. The variety of governance models and growth of local and sub-local models suggests that local context is critical for better understanding transit priorities and decision-making processes, especially in light of established associations between governance, power and other institutional characteristics. The analysis provided above suggests a need for more HOW and WHY questions in urban transport scholarship to better align academic knowledge with local practice: Why do local policy makers select certain strategies or forefront particular goals? How do local officials implement abstract ideas and ‘best practices’ across different contexts? Why do planning professionals pursue particular outcomes and how are their choices influenced by the location, history and social-cultural aspects of a location?

The typology outlined in the paper above will help advance inquiry into public transit governance in the United States. Scholars of urban transport are not currently well positioned to answer these important practice-oriented questions, as we lack a robust literature on the nature of transport governance. As our analysis illustrates, there is considerable variation in formal organizational structures that guide decision making within transit agencies. In our sample, 76% (52) of the transit providers are governed by boards of directors whose membership and representation constitute different power arrangements between city, county and regional stakeholders that are unexplored. City-level agencies are more common in the western part of the country and public authority models in the east and in the Midwest there is a pattern of city-level agencies operating concurrently with county-level agencies. This suggests the need for caution when comparatively analyzing systems located in different parts of the country as formal decision-making structures may serves a unrecognized constraints on action.