Microclimate of Urban Canopy Layer and Outdoor Thermal Comfort: A Case Study in Pavlou Mela, Thessaloniki

Abstract

:1. Introduction

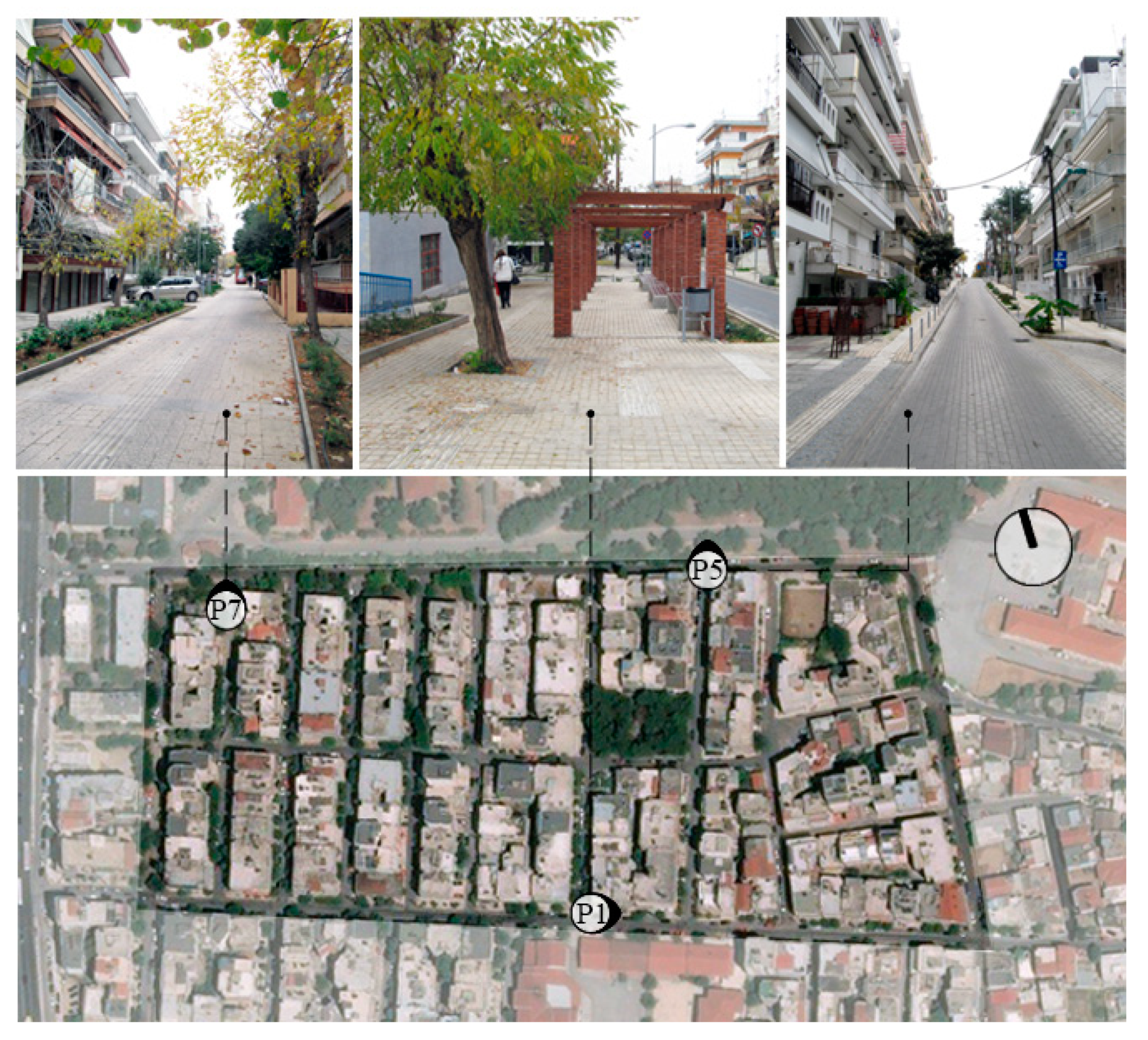

2. Case Study

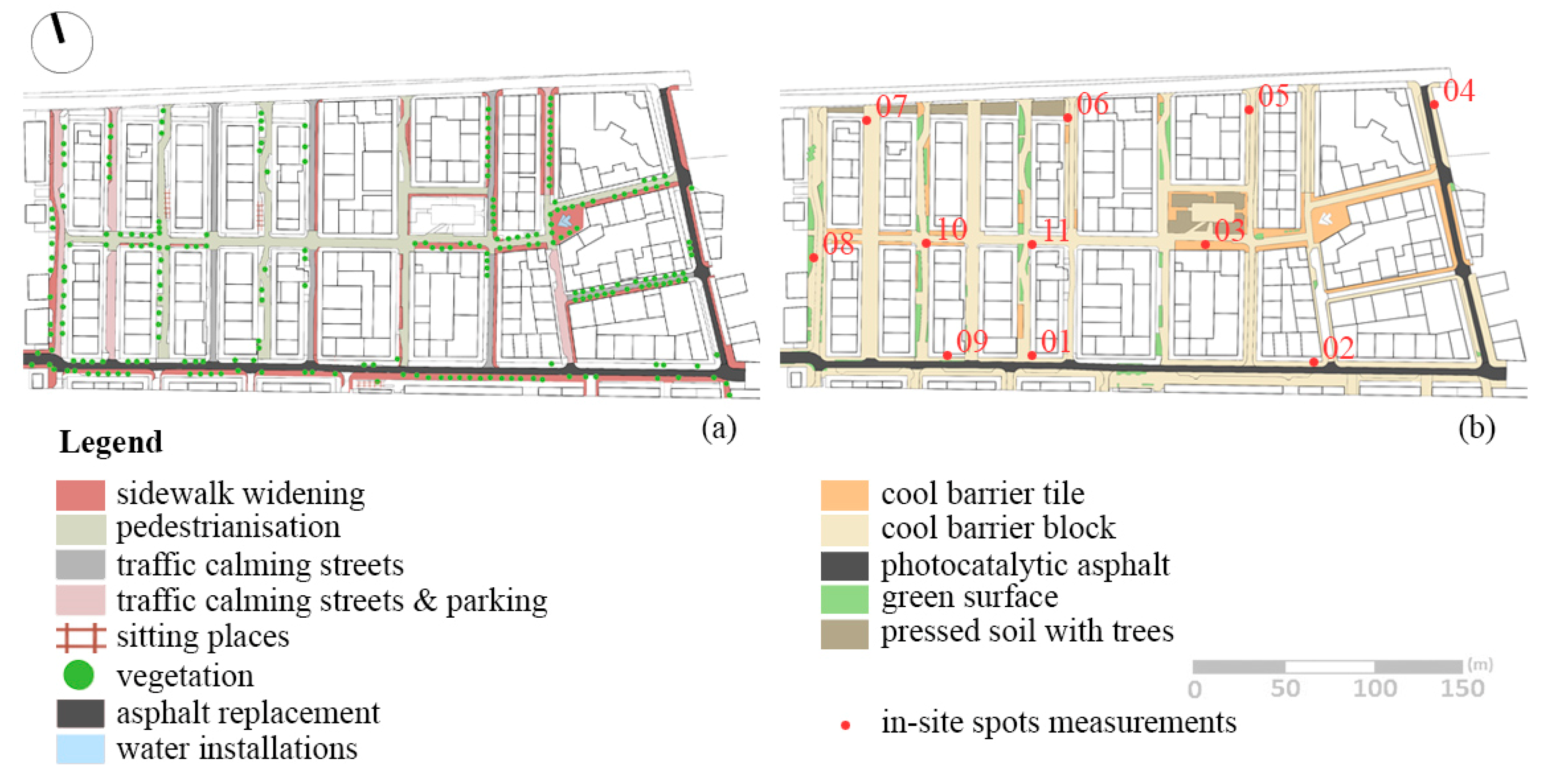

2.1. Main Strategies of Microclimatic Mitigation and Thermal Comfort

2.1.1. Cool Pavement Materials

2.1.2. Urban Green

2.1.3. Water Surface

2.2. Description of the Microclimate Specifically of Urban Canyon

- (i)

- Sky view factor (SVF) (4): The first element taken into consideration represents the radiant exchange with the celestial vault, and consequently, the temperatures (Ta, Ts, etc) are linked to the urban context according to the amount of radiation present on the entire road surface. The SVF [38] of the site in question corresponds to a relatively low value on average 0.30–0.40.

- (ii)

- Orientation: Describes the direction of the canyon.

- (iii)

- Height-to-width (H/W ratio): Describes the proportion of the average building height to the width of the street. This fact is particularly important because its value affects the radiation and the modification of the direction and intensity of the winds in urban canyons. In this study, the H/W ratio is characterized by an average of 0.80–1.20; while the surface of the building façades has an albedo of 0.30 (concrete) with continuous fronts.

- (iv)

- Green-trees: Trees according to the size, type and distribution are able to intercept solar radiation (shading), and also decrease the air temperature (evapotranspiration). The present case study consists of a percentage of approximately 63% of deciduous types for an average size <12–18m with a predominantly linear distribution.

- (v)

- Innovative cool pavement materials: According to the radiant properties of the materials, the reflectance (α) and emissivity (ε) of solar radiation are shown in Table 2.

3. Methodology

3.1. In-Site Spots Measurements

3.2. Microclimate and Microspecific Simulations

3.3. Potential and Limitations of the Software Used: ENVImet Pro & RayMan Pro

4. Results and Comparison

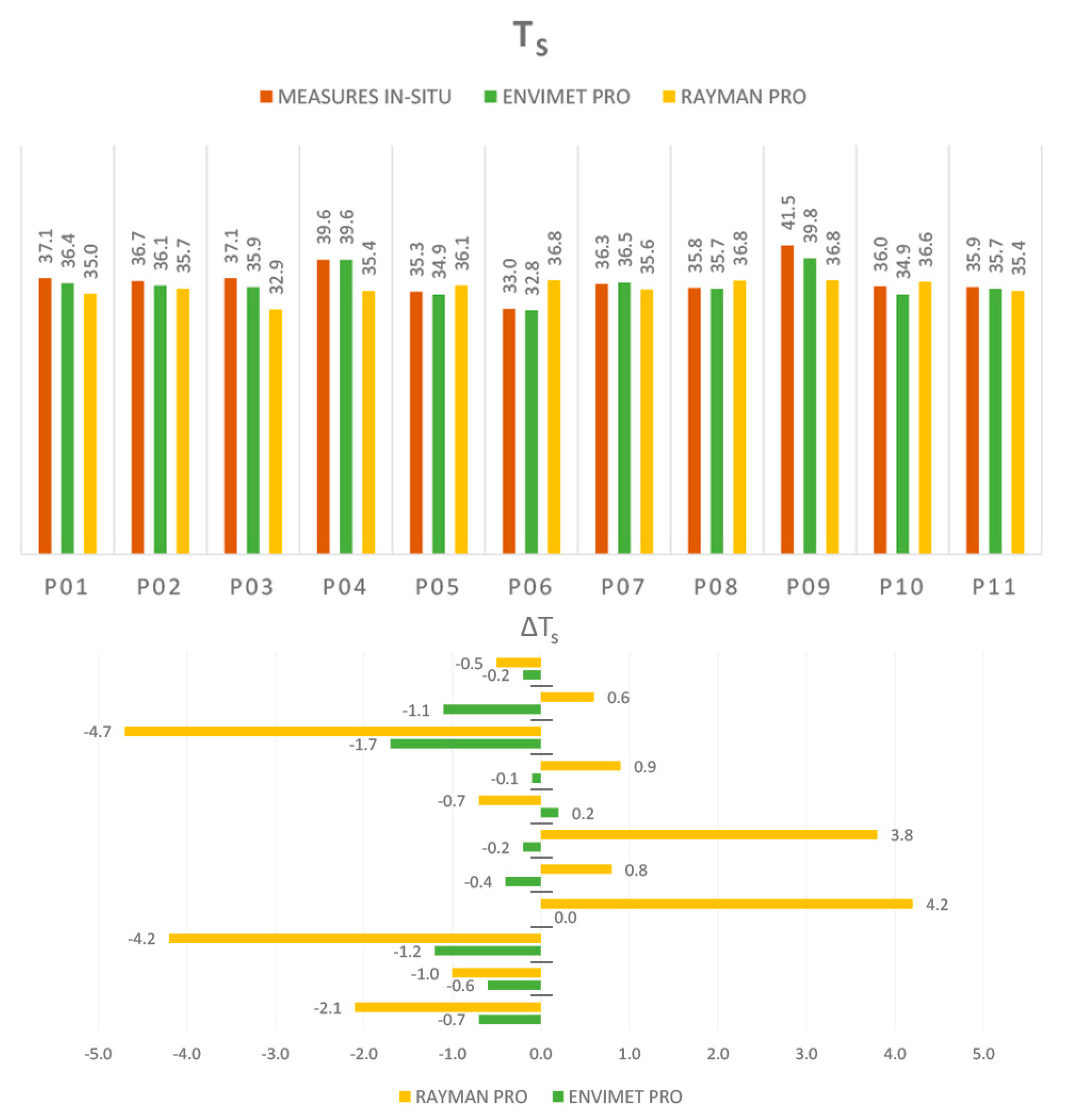

4.1. Comparison of the Simulated Results of the Average Ta and Ts Values with the Measurements in the Field at Each Spots

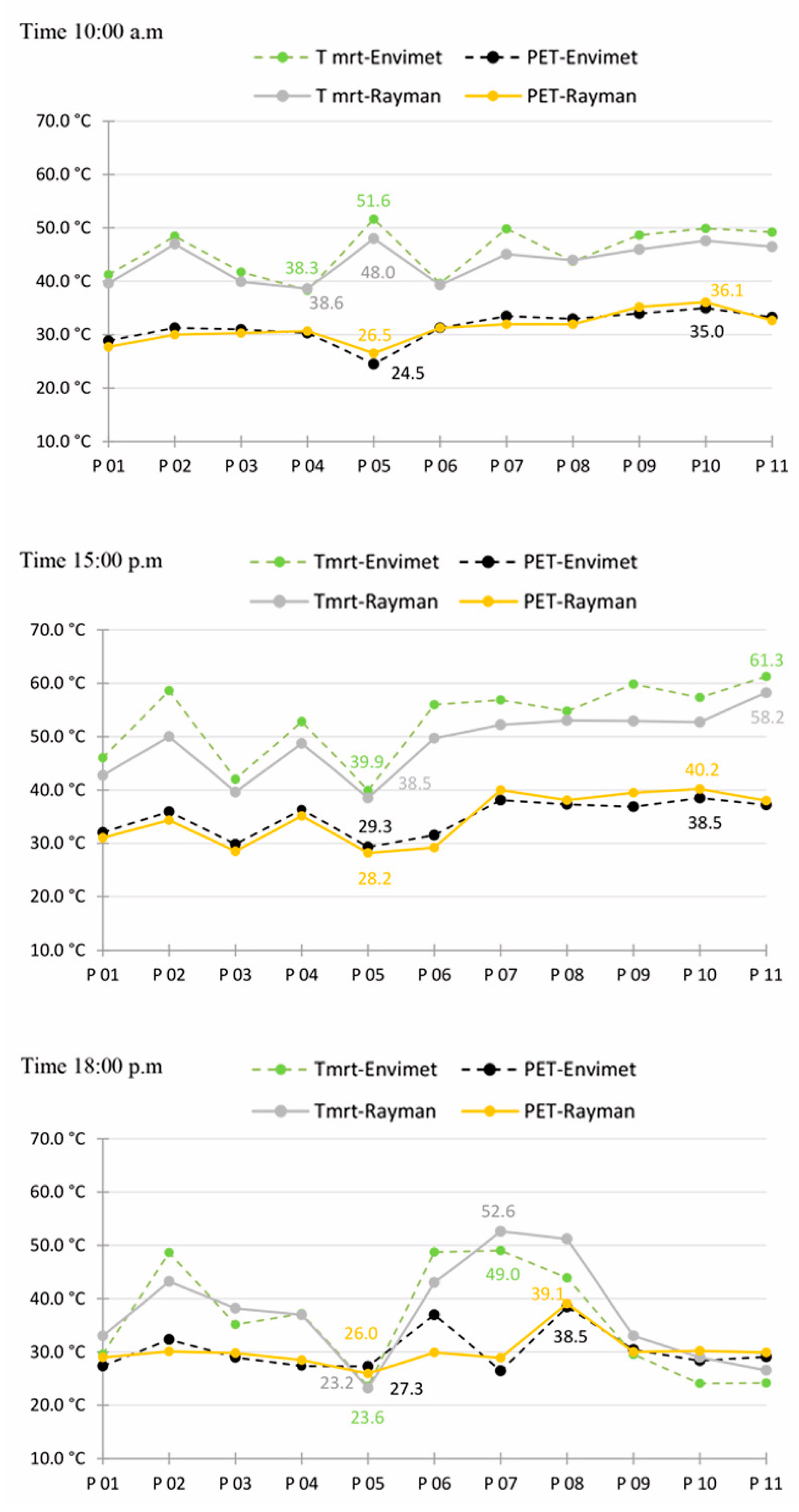

4.2. Verification and Evaluation of Tmrt and PET Values, Comparing the Different Points Examined

5. Conclusions

6. Notes

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change. Climate Change: Synthesis Report 2014. Contribution of Working Group I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In Proceedings of the Parties at its twenty-first session (COP 21) and the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol at its eleventh session (CMP 11), Paris Agreement, COP 21 or CMP 11, Pairs, France, 30 November–11 December 2015.

- European Climate Adaptation Platform. Climate—ADAPT-Sharing Adaptation Information across Europe. Available online: http://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/ (accessed on 2 March 2018).

- European Commission. Community Research and Development Information Service. Horizon 2020 Call ReCO2ST; Publication Office: Luxembourg, 2017.

- Coaffee, J.; Lee, P. Urban Resilience: Planning for Risk, Crises and Uncertainty; Planning-Environment-Cities; Publication Office: London, UK, 2016; ISBN-10: 1137288833. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei, P.; Haghighat, F. Approaches to study urban heat island—Abilities and limitations. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 2192–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Specialized Agency of the United Nation. Homepage. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/urban_health/situation_trends/urban_population_growth_text/en/ (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- EPA. Reducing Urban Heat Islands: Compendium of Strategies, Urban Heat Island Basics; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-06/documents/basicscompendium.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2019).

- Hayhoe, K.; Sheridan, S.; Kalkstein, L.; Greene, S. Climate change, heat waves, and mortality projections for Chicago. J. Great Lakes Res. 2010, 36, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassid, S.; Santamouris, M.; Papanikolaou, N.; Linardi, A.; Klitsikas, N.; Georgakis, C.; Assimakopoulos, D.N. The effect of the Athens heat island on air conditioning load. Energy Build. 2000, 32, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmohamadi, P.; Che-Ani, A.I.; Maulud, K.N.A.; Tawil, N.M.; Abdullah, N.A.G. The Impact of Anthropogenic Heat on Formation of Urban Heat Island and Energy Consumption Balance. Urban Stud. Res. 2011, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Levermore, G. Designing urban spaces and buildings to improve sustainability and quality of life in a warmer world. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4558–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erell, E.; Pearlmutter, D.; Boneh, D.; Kutiet, P.B. Effect of high-albedo materials on pedestrian heat stress in urban street canyon. Urban Clim. 2014, 10, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behringer, W. A Cultural History of Climate, 1st ed.; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780745645292. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysoulakis, N.; Vogt, R.; Young, D.; Grimmond, C.S.B.; Spano, D.; Marras, S. ICT for Urban Metabolism: The case of BRIDGE. Environ. Inform. Ind. Environ. Prot. 2009, 2, 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulou, M. Designing Open Spaces in the Urban Environment: A Bioclimatic Approach: RUROS—Rediscovering the Urban Realm and Open Spaces; Center for Renewable Energy Sources: Attiki, Greece, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulou, M. Outdoor thermal comfort. Front. Biosci. 2011, 3, 1552–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Program National E.P. PERAA (ESPA 2007–2013). Bioclimatic Improvement Program for Public Open Spaces. Available online: http://www.cres.gr/epperaa/bioclimat_anavathm.html (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- Chatzidimitriou, A.; Kanouras, S.; Topli, L.; Bruse, M. Evaluation of a sustainable urban redevelopment project in terms of microclimate improvements. In Proceedings of the (PLEA 2017)—Sustainable Architecture for a Renewable Future, Edinburgh, UK, 3–5 July 2017; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318404396 (accessed on 27 July 2019).

- Karakounos, I.; Dimoudi, A.; Zoras, S. The influence of bioclimatic urban redevelopment on outdoor thermal comfort. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanger, P.O. Thermal Comfort: Analysis and Application in Environmental Engineering; Mc-Graw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio Alfano, F.R.; Igor Palella, B.; Riccio, G.; Toftum, J. Fifty years of Fanger’s equation: Is there anything to discover yet? Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2018, 66, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höppe, P. The physiological equivalent temperature—A universal index for the biometeorological assessment of the thermal environment. Int. J. Biometeorol. 1999, 43, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matzarakis, A.; Rutz, F. Application of the Rayman Model in Urban Environments Freiburg; Meteorological Institute, University of Freiburg: Freiburg, Germany, 2010; Available online: https://ams.confex.com/ams/19Ag19BLT9Urban/techprogram/paper_169963.htm (accessed on 27 July 2019).

- Martinelli, L.; Matzarakis, A. Influence of height/width proportions on the thermal comfort of courtyard typology for Italian climate zones. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 29, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröde, P.; Fiala, D.; Blazejczyk, K.; Holmér, I.; Jendritzky, G.; Kampmann, B.; Tinz, B.; Havenith, G. Deriving the operational procedure for the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio Alfano, F.R.; Olesen, B.W.; Palella, B.I. Povl Ole Fanger’s impact ten years later. Energy Build. 2017, 152, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Kolokotsa, D. Urban Climate Mitigation Techniques; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-415-71213-2. [Google Scholar]

- Santamouris, M. Using cool pavements as a mitigation strategy to fight urban heat island a review of the actual developments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Xirafi, F.; Gaitani, N.; Spanou, A.; Saliari, M.; Vassilakopoulou, K. Improving the Microclimate in a Dense Urban Area Using Experimental and Theoretical Techniques—The Case of Marousi, Athens. Int. J. Vent. 2012, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Gaitani, N.; Spanou, A.; Saliari, M.; Giannopoulou, K.; Vasilakopoulou, K.; Kardomateas, T. Using cool paving materials to improve microclimate of urban areas—Design realization and results of the flisvos project. Build. Environ. 2012, 53, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulia, E.; Santamouris, M.; Dimoudi, A. Monitoring the effect of urban green areas on the heat island in Athens. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 156, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimoudi, A.; Nikolopoulou, M. Vegetation in the urban environment: Microclimatic analysis and benefits. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudo, G. Thermal comfort in green spaces. In Green Structures and Urban Planning; Sistemi Editoriali: Milan, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ken-ichi, N.; Kohno, T.; Misaka, I. Experimental Study on Evaporative Cooling of Fine Water Mist for Outdoor Comfort in the Urban Environment. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Countermeasures to Urban Heat Island, Venice, Italy, 13–15 October 2014; pp. 1288–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Santamouris, M.; Ding, L.; Fiorito, F.; Oldfield, P.; Osmond, P.; Paolini, R.; Prasad, D.; Synnefa, A. Passive and active cooling for the outdoor build environment—Analysis and assessment of the cooling potential of mitigation technologies using performance data from 220 large scale projects. J. Sol. Energy 2017, 154, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, F.; Golasi, I.; Castaldo, V.L.; Piselli, C.; Pisello, A.L.; Salata, F.; Ferrero, M.; Cotana, F.; Vollaro, A. On the impact of Innovation materials on outdoor thermal comfort of pedestrians in historical urban canyons. Renew. Energy 2018, 118, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drach, P.; Barbosa, G.; Corbella, O. Densification Process of Copacabana Neighborhood over 1930, 1950 and 2010 Decades: Comfort indexes. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Countermeasures to Urban Heat Island, Venice, Italy, 13–15 October 2014; pp. 1348–1361. [Google Scholar]

- TOTEE, Technical Guideline 20701-2. Thermophysical Properties of Structural Materials and Testing of Insulating Adequacy of Buildings; Technical Chamber of Greece: Athens, Greece, 2010.

- Huttner, S.; Bruse, M. Numerical modeling of the urban climate—A preview on envi-met 4.0. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Urban Climate (ICUC-7), Yokohama, Japan, 29 June–3 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Matzarakis, A.; Rutz, F.; Mayer, H. Modelling radiation fluxes in simple and complex environments—Application of the RayMan model. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2007, 51, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidimitriou, A.; Liveris, P.; Bruse, M.; Topli, L. Urban Redevelopment and Microclimate Improvement: A Design Project in Thessaloniki, Greece. In Proceedings of the (PLEA2013)—29th Conference, Sustainable Architecture for a Renewable Future, Munich, Germany, 10–12 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Matzarakis, A.; Mayer, H. Another kind of environmental stress: Thermal stress. WHO Collaborating Centre for Air Quality Management and Air Pollution Control. Newsletter 1996, 18, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

| Specific Objectives of the Program E.P.PERAA [ESPA 2007–2013) | Validation Ante-Operam 2011 | Verification Post-Operam 2016 | ΔOperam [2011–2016] °C | ΔOperam [2011–2016] % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ob 01: average air temperature Ta = −5.8 (°C), z = 1.80 m—30 July | +33.9 | +28.1 | −5.8 | −17.0 |

| Ob 02: average surface temperature Ts = −7.9 (°C), z = 0.00 m—30 July | +37.9 | +30.0 | −7.9 | −13.3 |

| Ob 03: the sum of the base grades 26 °C, CDH = −85.8%, z = 1.80 m—21 June | +62.2 | + 8.8 | −53.4 | −85.8 |

| Ob04: comfort index PMV = −47.3%, z = 1.80 m—21 June | +2.4 | +1.5 | −0.9 | −37.4 |

| Material | Albedo (α) | Emissions (ε) | Percentage of the Total Area of the Intervention (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| photocatalytic asphalt | ~0.50 | - | 8.15 |

| cool barrier tile white | 0.81 | 0.92 | 2.25 |

| cool barrier tile beige | 0.72 | 0.90 | 5.50 |

| cool barrier block grey | 0.47–0.56 | 0.88 | 19.54 |

| cool barrier block beige | 0.58 | 0.89 | 47.58 |

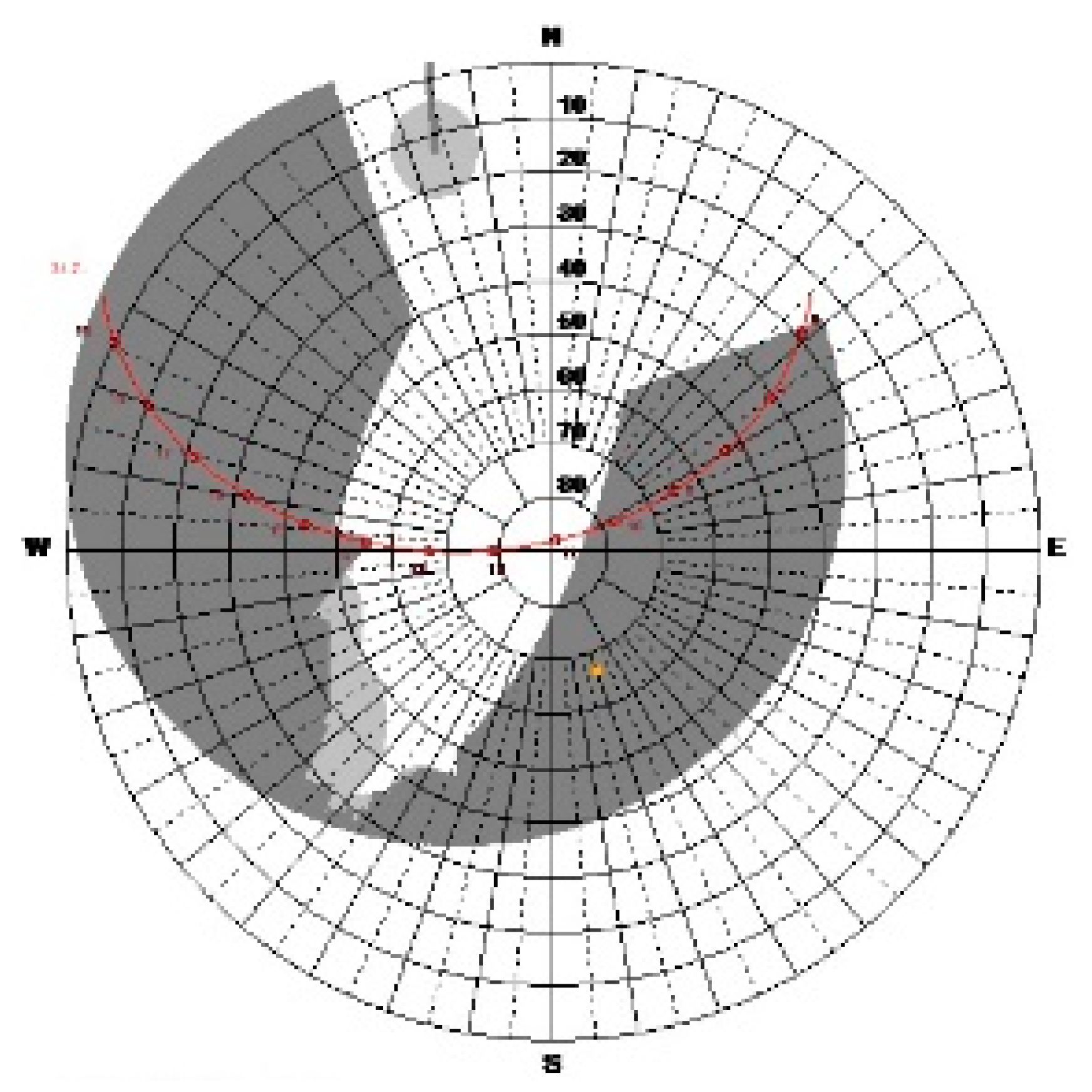

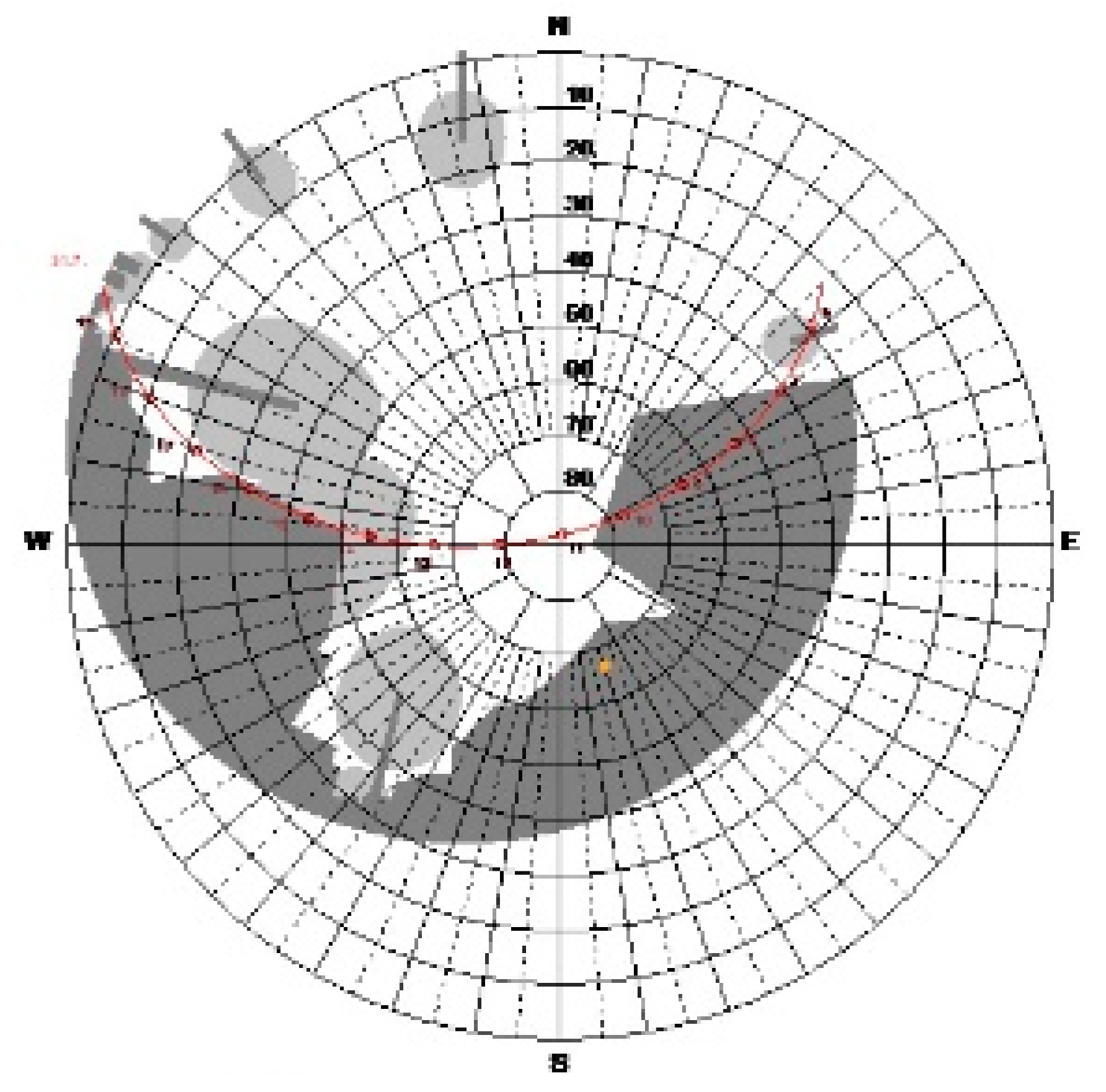

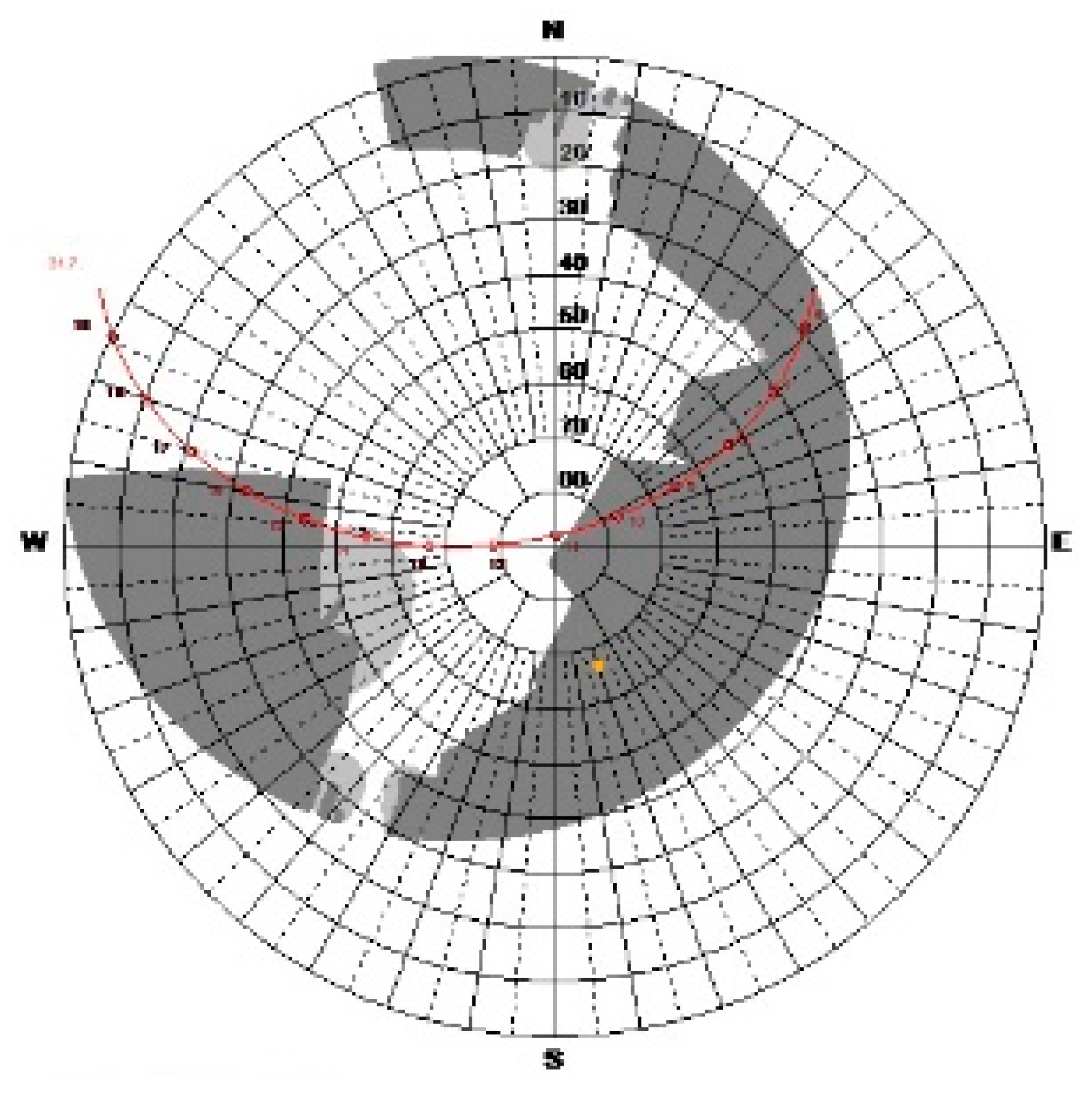

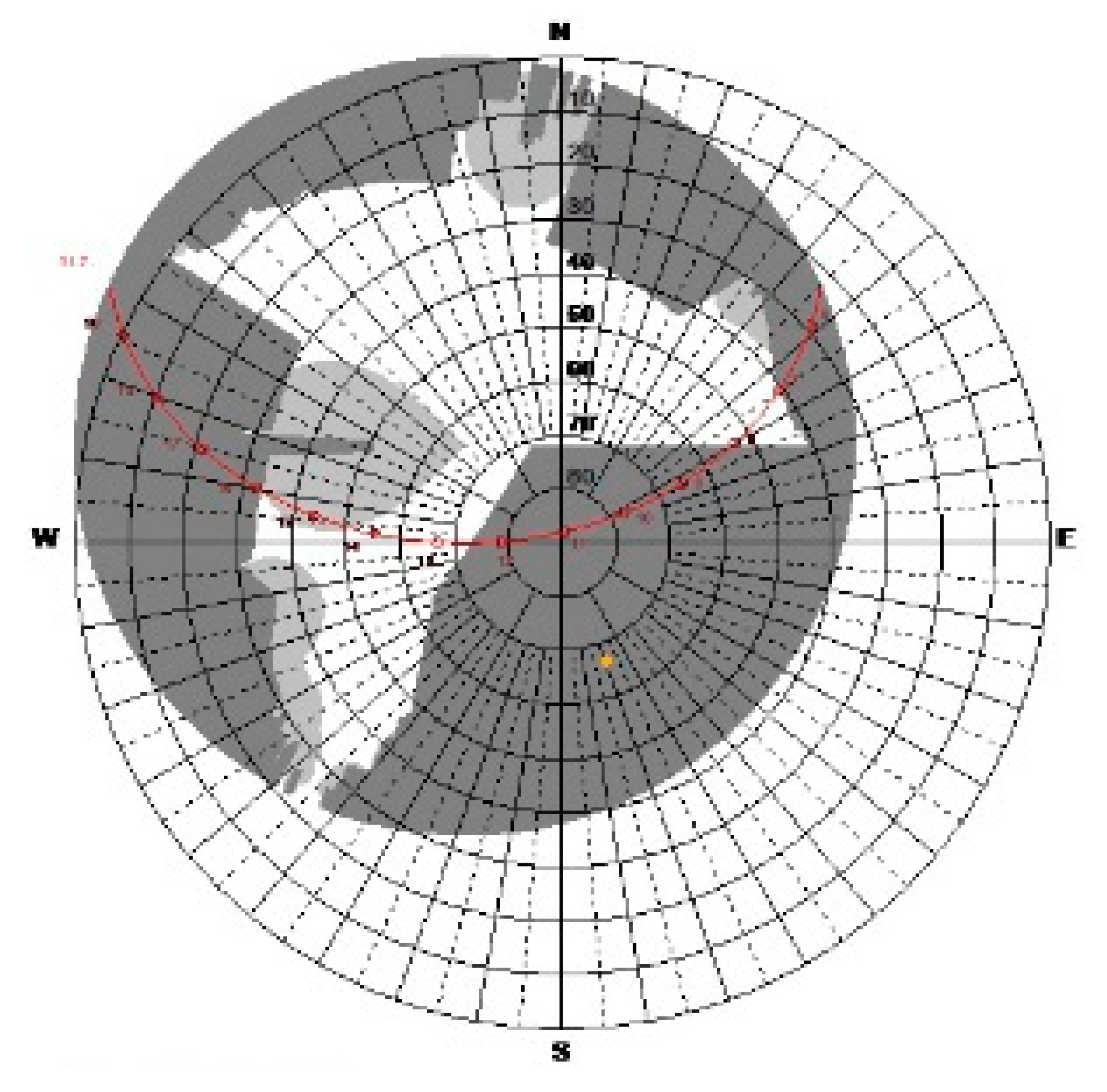

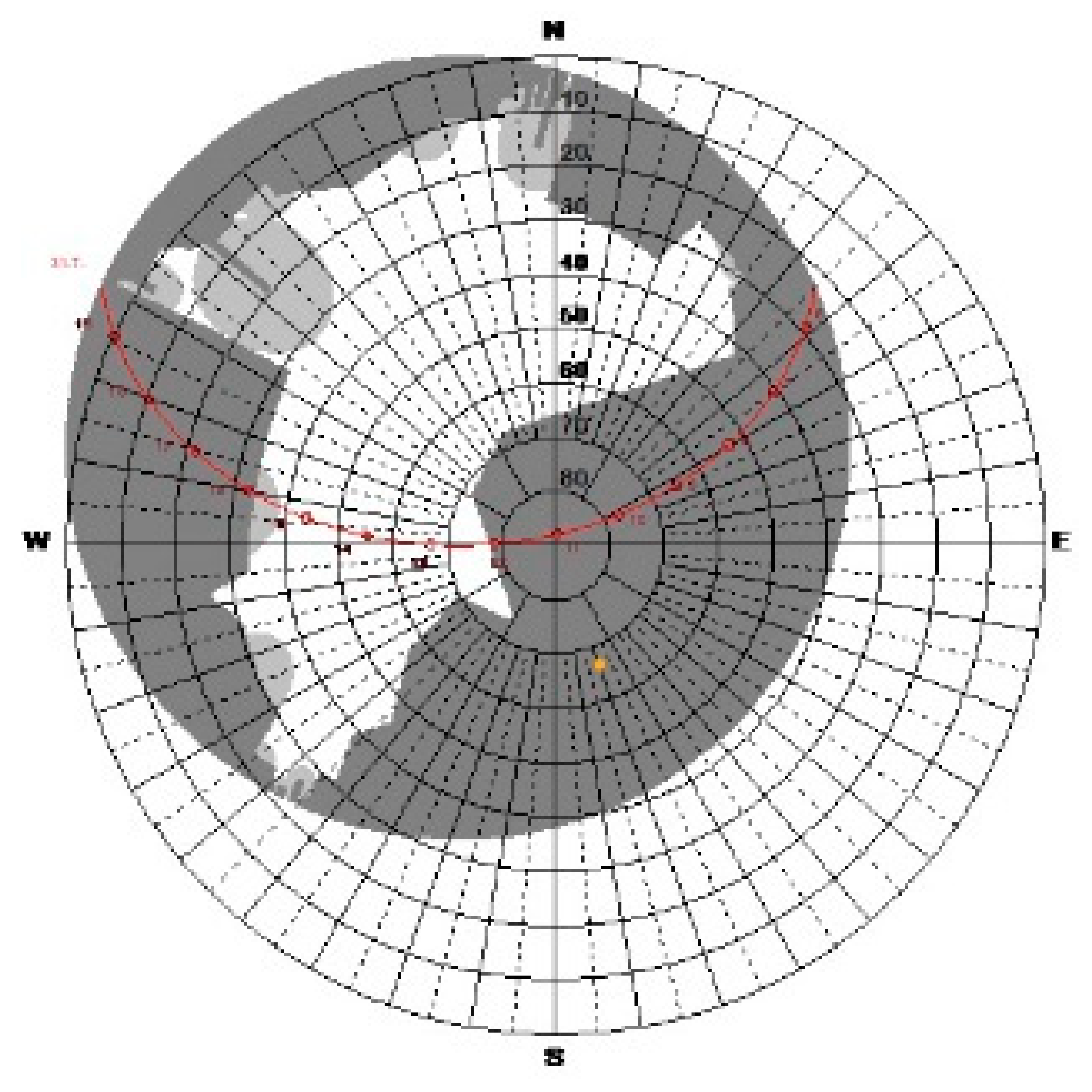

| Spots | SVF(5) | Orientation | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H/W& Green-Trees | Innovative Materials c.p | |||

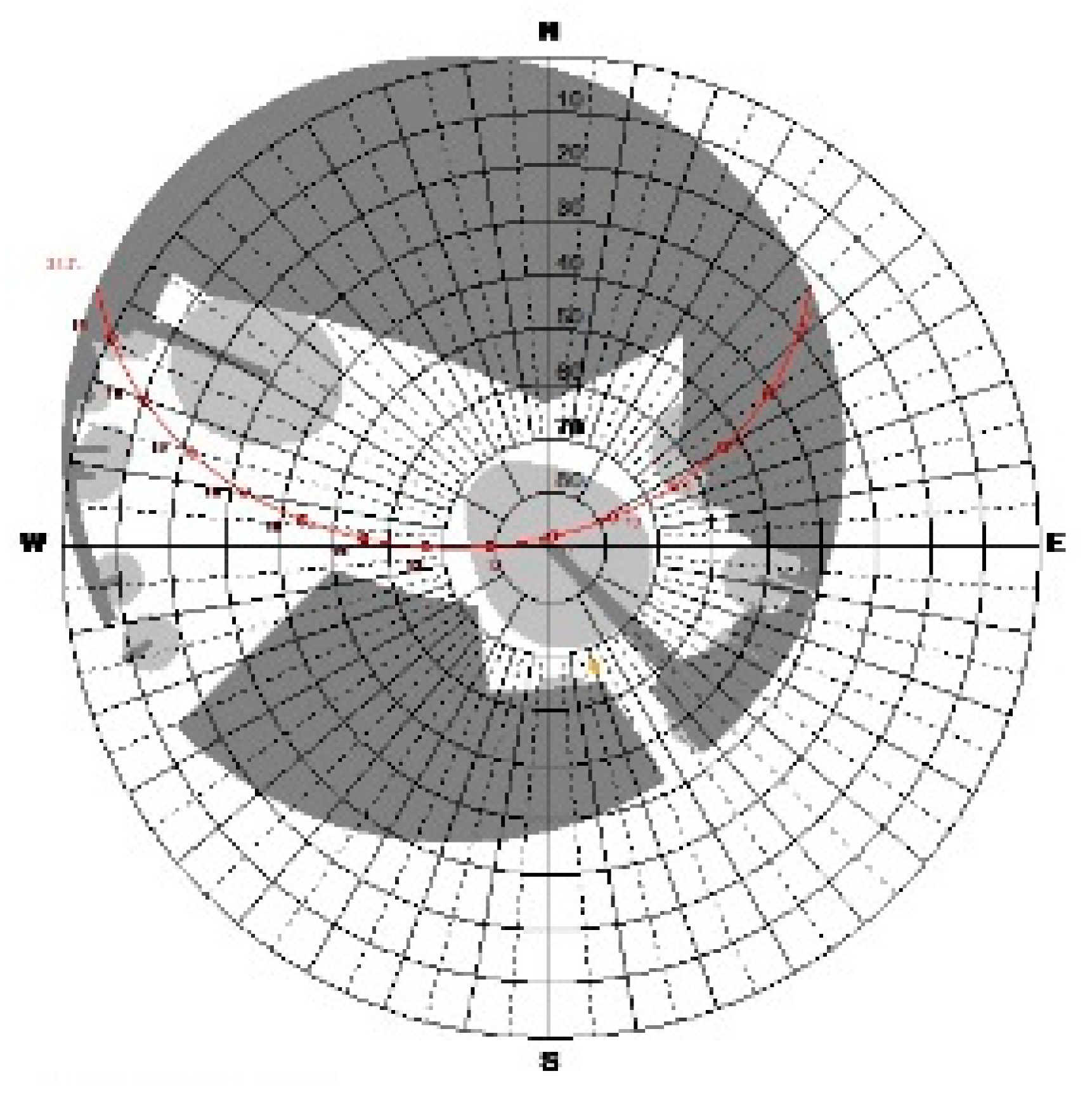

| 01 |  | South-West | The first point in question is located at the intersection of the streets Grigoriou Lampraki & Othonos, in a main road surrounded on three sides by medium buildings (9–18 m), exposed to solar radiation mainly in the afternoon hours, while regarding incidence of the shadow factor shows the remarkable effectiveness of existing trees of height 6–7 m with perennial leaves. | The combination of the main materials used for the flooring presents: photocatalytic coating for the street (via Gr. Lampraki), gray ‘cool’ barrier blocks (via Othonos), walkway covered by barrier blocks ‘cool’ color beige, sensory journey for the visually impaired with tactile concrete slabs of white color. |

| 02 |  | South-East | The second highlight is located on one of the main local roads of particular frequency, in Grigoriou Lampraki street, characterized by the average continuity of the building front (12–21 m). In particular, the area is surrounded by rows of deciduous trees and perennials of height ˂5–6 m, exposed both East and West to shield the driveway. | The flooring materials applied to the walkway are composed of beige ‘cool’ barrier blocks, while the road presents the photocatalytic treatment combined with gray ‘cool’ barrier blocks that delimit the parking areas. |

| 03 |  | South-East | The third point in question falls in an area completely dedicated to pedestrians inside the neighborhood in Geog. Seferi road, located in front of an urban square covered with trees of 3–15 m height, which generate shade. The point is presented in a path delimited by flowerbeds in different tiers and surrounded by buildings of medium height, between 12–15 m. | The flooring materials are covered with: beige ‘cool’ barrier tiles and beige ‘cool’ barrier blocks. |

| 04 |  | North-East | The fourth significant point was made on the Koustali route in a morphologically open area, surrounded by low buildings (6–9 m) with greater openness SVF, while the organization of the trees of height ˂4–5 m with perennial leaves are placed in a linear form along the road axis on both the West and East sides. | The flooring materials are covered with: beige ‘cool’ barrier tiles and beige ‘cool’ barrier blocks. |

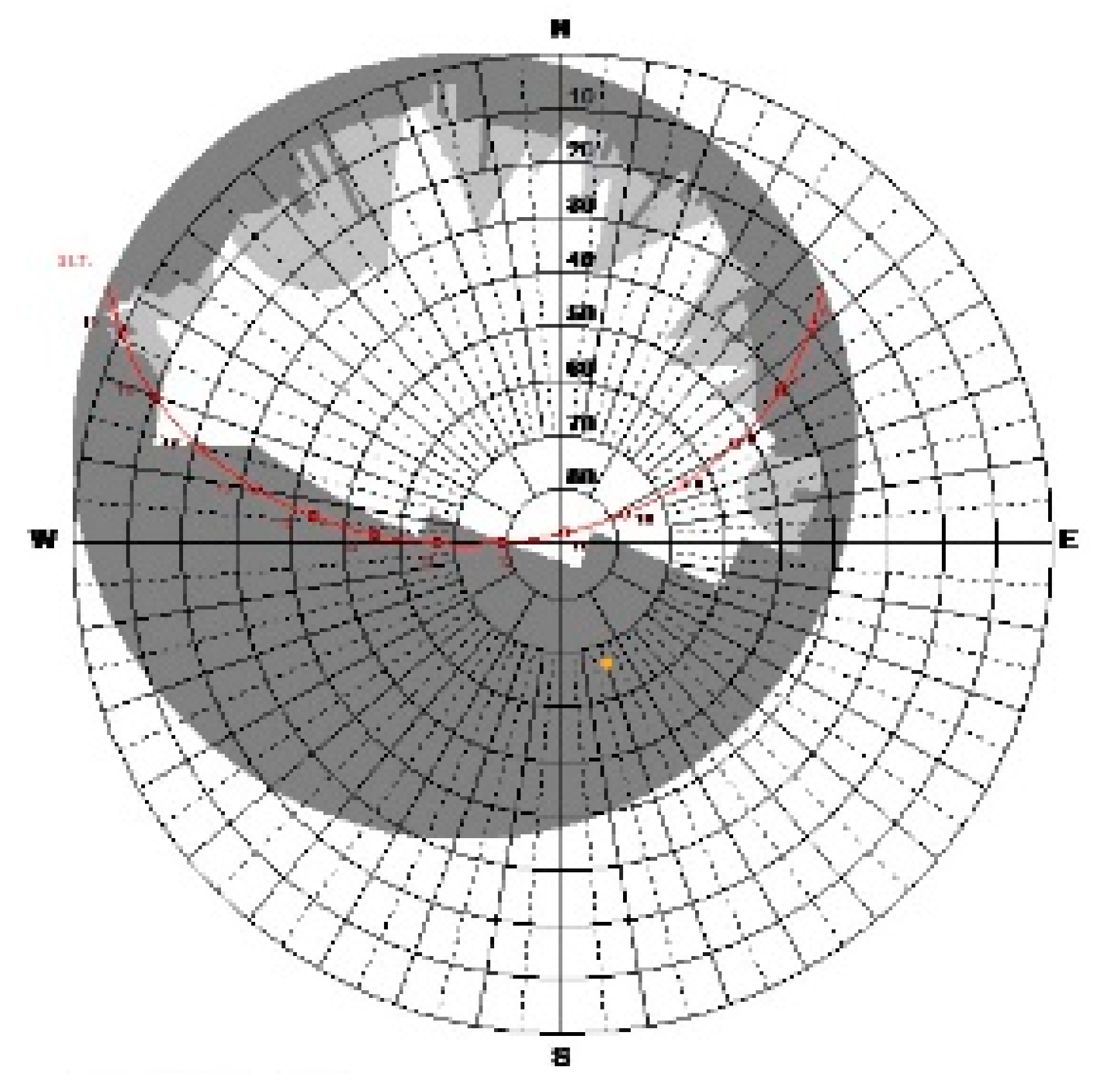

| 05 |  | North-East | The fifth point is executed in Papanastasiou road, it has continuous building fronts (12–15 m), while the green system does not play any role because it is almost non-existent in the surrounding range. | The street is covered with gray ‘cool’ barrier blocks, while the walkway contains beige ‘cool’ barrier blocks. |

| 06 |  | North | The sixth specific point was observed on Othonos street, surrounded by continuous front buildings of medium height (12–15 m) and by the widening of the 7 m road (i.e., the ratio H/W to about 0.60–0.40); furthermore, there are stretches of deciduous trees of 2–3 m in the West, which generate in case of an accident the shading effect at the moment of detection, because they do not yet possess sufficient growth. | Application materials associated with paving are made of beige ‘cool’ barrier blocks on the street, while the pedestrian path is redesigned with beige ‘cool’ barrier tiles. |

| 07 |  | North-West | The seventh survey was carried out at the intersection of the streets Thivon & Varnali, in front of an area of public car parks pertaining to the entrance of the psychiatric hospital (with different daily and weekly frequencies). The spatial configuration presents different heights of buildings (3–21 m) and is surrounded by trees of size between 3–8 m deciduous on the West side. | The flooring is covered with beige ‘cool’ barrier blocks. |

| 08 |  | West | The eighth specific point is taken from the survey on the site, at different times of the day, in a vehicular transit area (with moderate traffic) and pedestrian area, located in P. Tsandali street. The spatial configuration is partially open on the SW side with different heights of the buildings (9–12 m), while the SE side has continuity of the fronts of 4–7 floors. The green system of <12–18 m, integrated with the flowerbeds, arranged in rows of deciduous and perennial trees near the road. | The main materials used for the flooring were: the gray ‘cool’ barrier blocks for the street and the parking area, while the surfaces on the walkway are covered with beige ‘cool’ barrier blocks. |

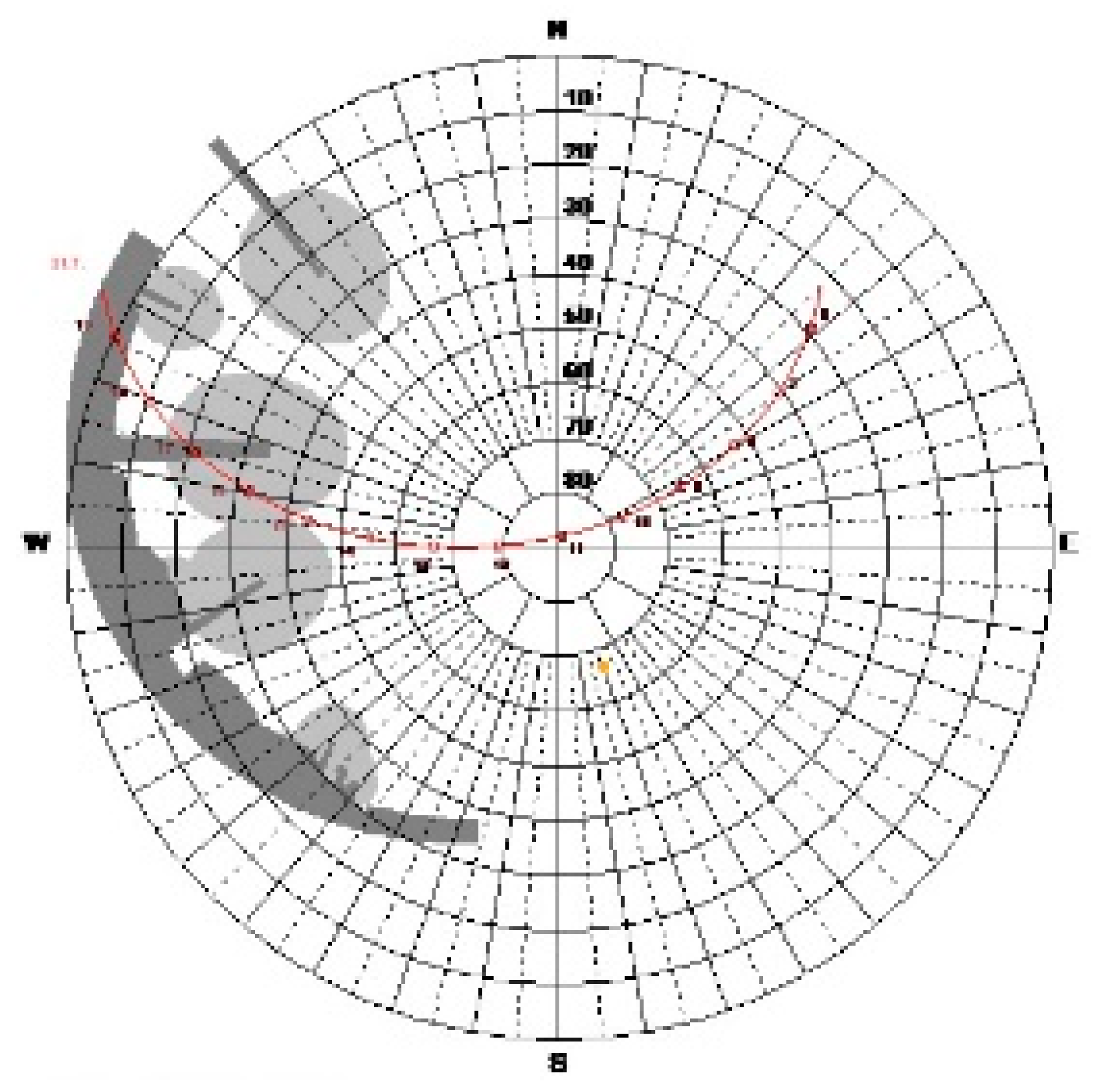

| 09 |  | South-West | The ninth important step on the field is located on the main street of Grigoriou Lampraki excessively busy; the site is characterized by buildings of medium height (9–18 m), while the impact of the green system is produced by trees of size <3–6 m deciduous and perennial, which are placed in rows along the road. | The combination of the flooring, with the thermophysical properties related to the individual materials, consists of: photocatalytic asphalt, gray ‘cool’ barrier blocks present in the parking area and beige ‘cool’ barrier blocks used for the construction of sidewalks. |

| 10 |  | North-West | The tenth experiment point is located at the pedestrian crossing with limited traffic between the streets Aggelou Sikelianou & Geog. Seferi, which has a H/W ratio of 0.72, between the pedestrianized width of 13 m and the height of the buildings of 15 m. The green shading elements are between 3–4 m long deciduous and perennial. | The materials configured in flooring are made of beige ‘cool’ barrier blocks of different sizes and ‘cool’ beige barrier tiles. |

| 11 |  | West | The eleventh point of detection is carried out on Manou Katraki street, surrounded by buildings of different heights (from 6 to 15 m), while the organization of deciduous and perennial trees of size between 6–9 m has two sides on the sides integrated with the flowerbeds, which delimit the completely pedestrianized area. | The main flooring materials consist of beige ‘cool’ barrier blocks of different sizes. |

| Input Parameters | Average Value |

|---|---|

| air temperature | 33.0 °C, 306.15 K |

| relative humidity | 37.4% |

| wind speed | 0.7 m/s |

| wind direction | 181.7° |

| barometric pressure | 1004.9 hPa |

| sky conditions: cloud cover (cc) | 0 (clear) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skoufali, I.; Battisti, A. Microclimate of Urban Canopy Layer and Outdoor Thermal Comfort: A Case Study in Pavlou Mela, Thessaloniki. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030084

Skoufali I, Battisti A. Microclimate of Urban Canopy Layer and Outdoor Thermal Comfort: A Case Study in Pavlou Mela, Thessaloniki. Urban Science. 2019; 3(3):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030084

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkoufali, Ioanna, and Alessandra Battisti. 2019. "Microclimate of Urban Canopy Layer and Outdoor Thermal Comfort: A Case Study in Pavlou Mela, Thessaloniki" Urban Science 3, no. 3: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030084

APA StyleSkoufali, I., & Battisti, A. (2019). Microclimate of Urban Canopy Layer and Outdoor Thermal Comfort: A Case Study in Pavlou Mela, Thessaloniki. Urban Science, 3(3), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030084