Regional Councils in a Global Context: Council Types and Council Elements

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Acknowledging the Regional Level

2. Regional Councils

- With regard to people in the regional council: How are the members of the council selected? How do they work together? In a general assembly? In specific committees?

- With regard to supporting elements for the regional councils: How is the council supported? Does administrative support through qualified staff exist? Does financial support exist?

- With regard to services provided by the regional council: What is the outcome of the work of the regional council? What services are provides for the involved municipalities, for the citizens?

- With regard to topics covered by the regional council: What topics does the council deal with? Is there a differentiation made between mandatory and voluntary topics? Are topics prioritized? Who decides which topics have to be worked on?

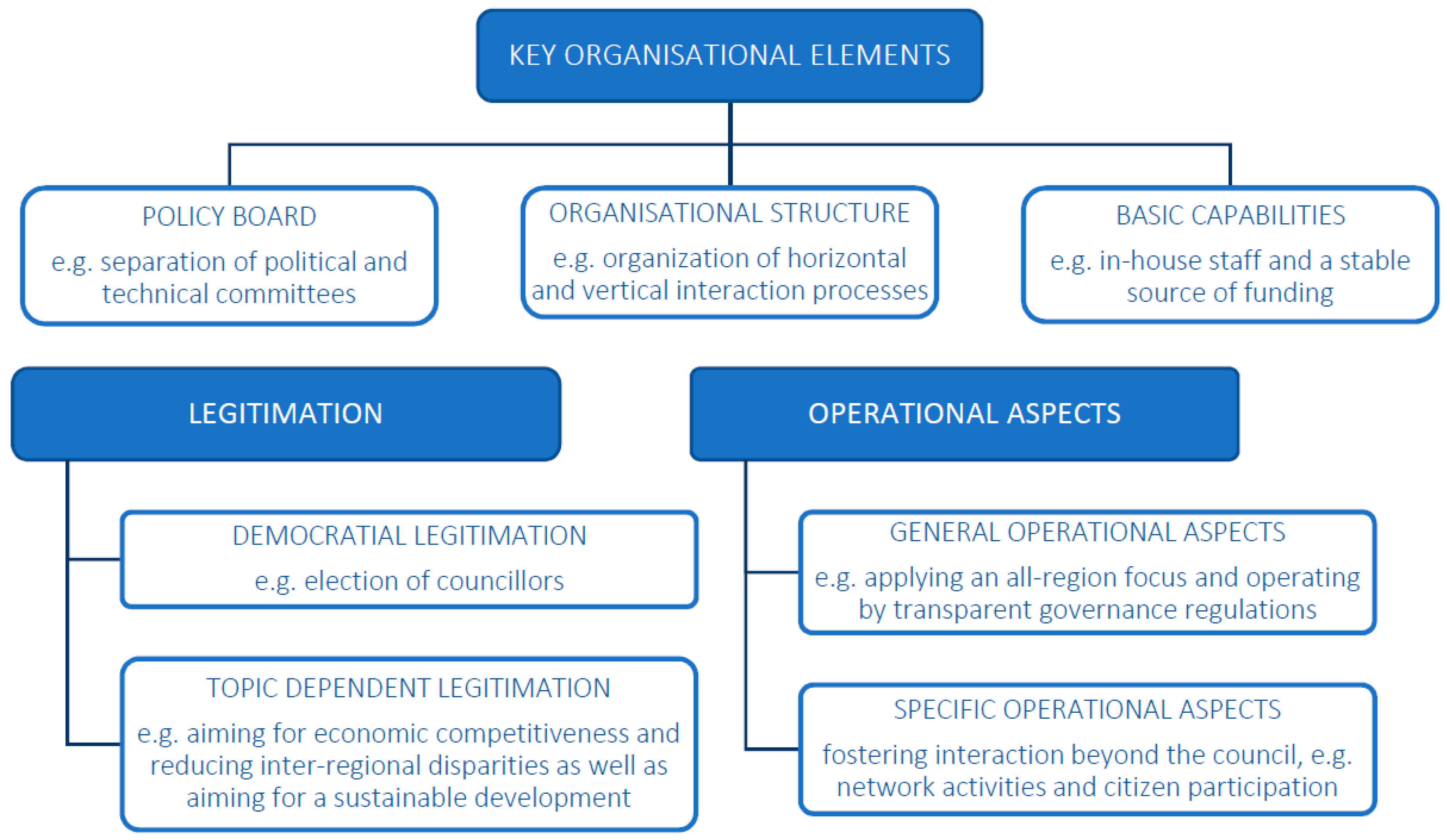

- key organizational elements,

- aspects regarding the legitimation of regional councils, and

- operational aspects pointing to aspects that help reaching the aims of regional council.

2.1. Organizational Aspects

2.2. Aspects of Legitimation

2.3. Operational Aspects

3. Research Methods

- In a first step, the webpages of the sample regions have been searched for information shedding light on how the three main criteria (organizational aspects, aspects of legitimation, and operational aspects) are performed in the respective sample region (see list in Table 1).

- In a second step, additional information of and (subjective) evaluations about the three main criteria have been gained through semi-structured interviews and questionnaires.

- In a third step, information gained in interviews and questionnaires have been back-checked through a search within documents and on webpages.

- In a fourth step, the gained information has been related to the subcategories and each subcategory has been evaluated 2, 1, or 0 for each regional council.

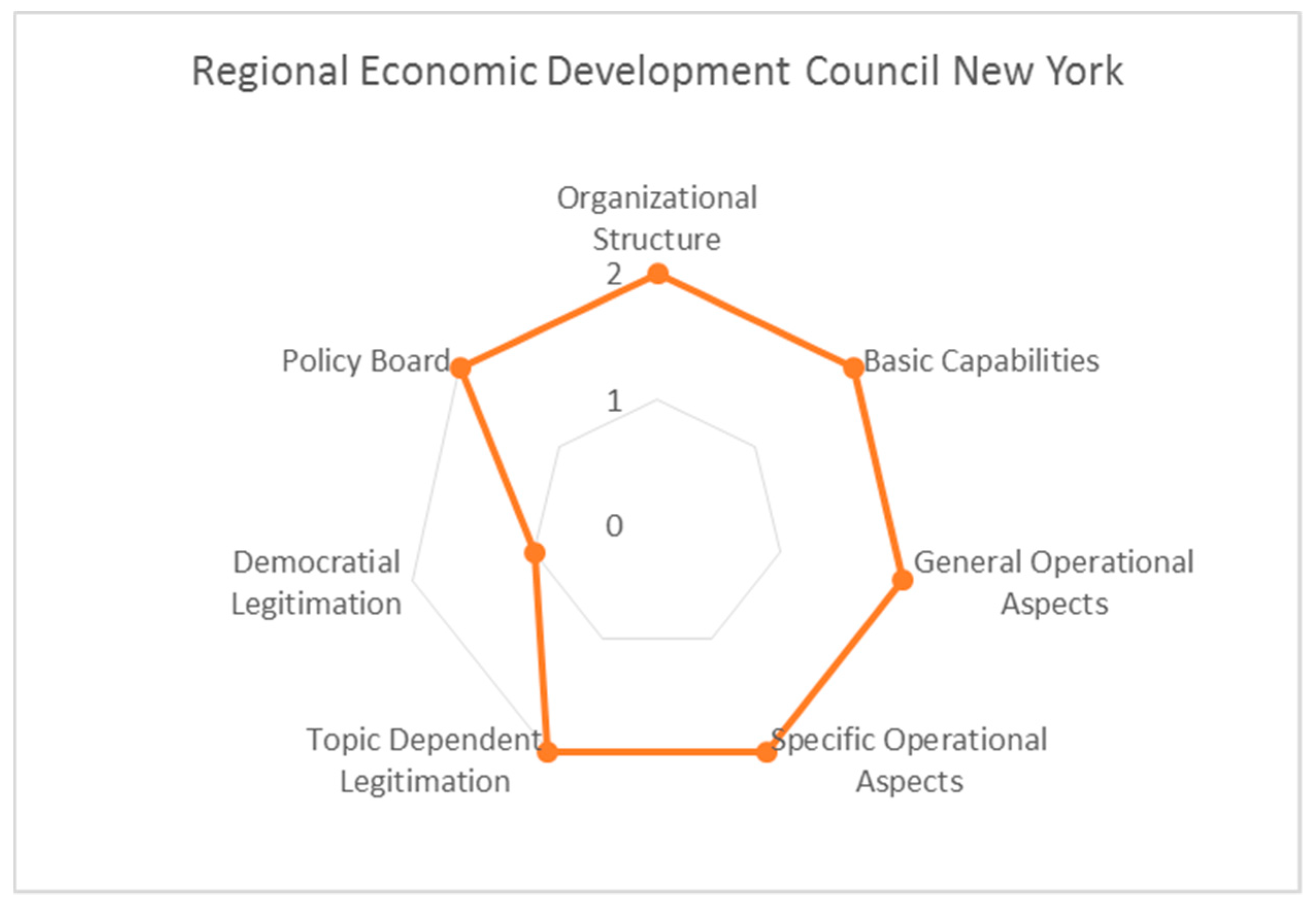

4. Results

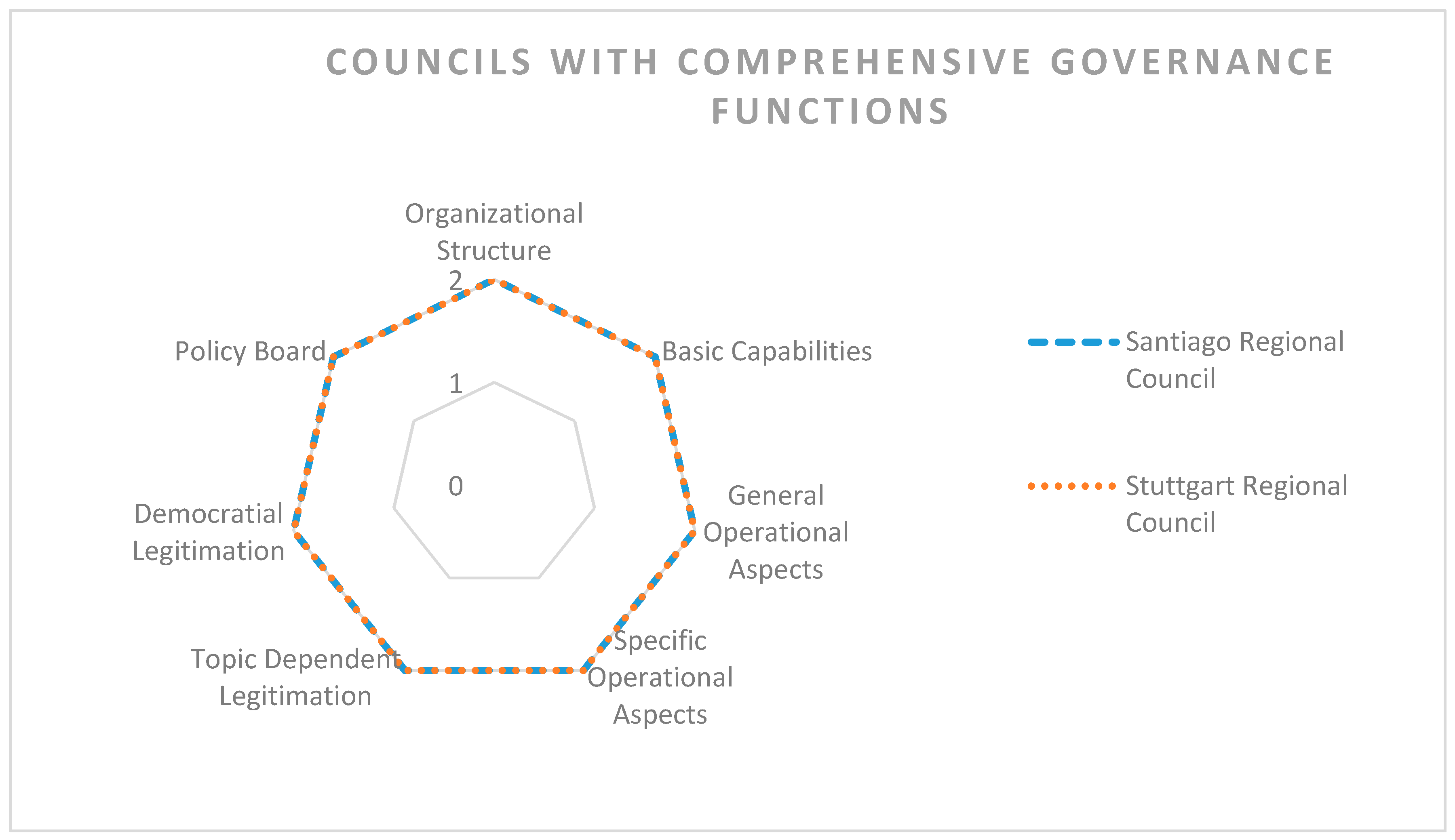

4.1. Regional Councils with Comprehensive Governance Functions

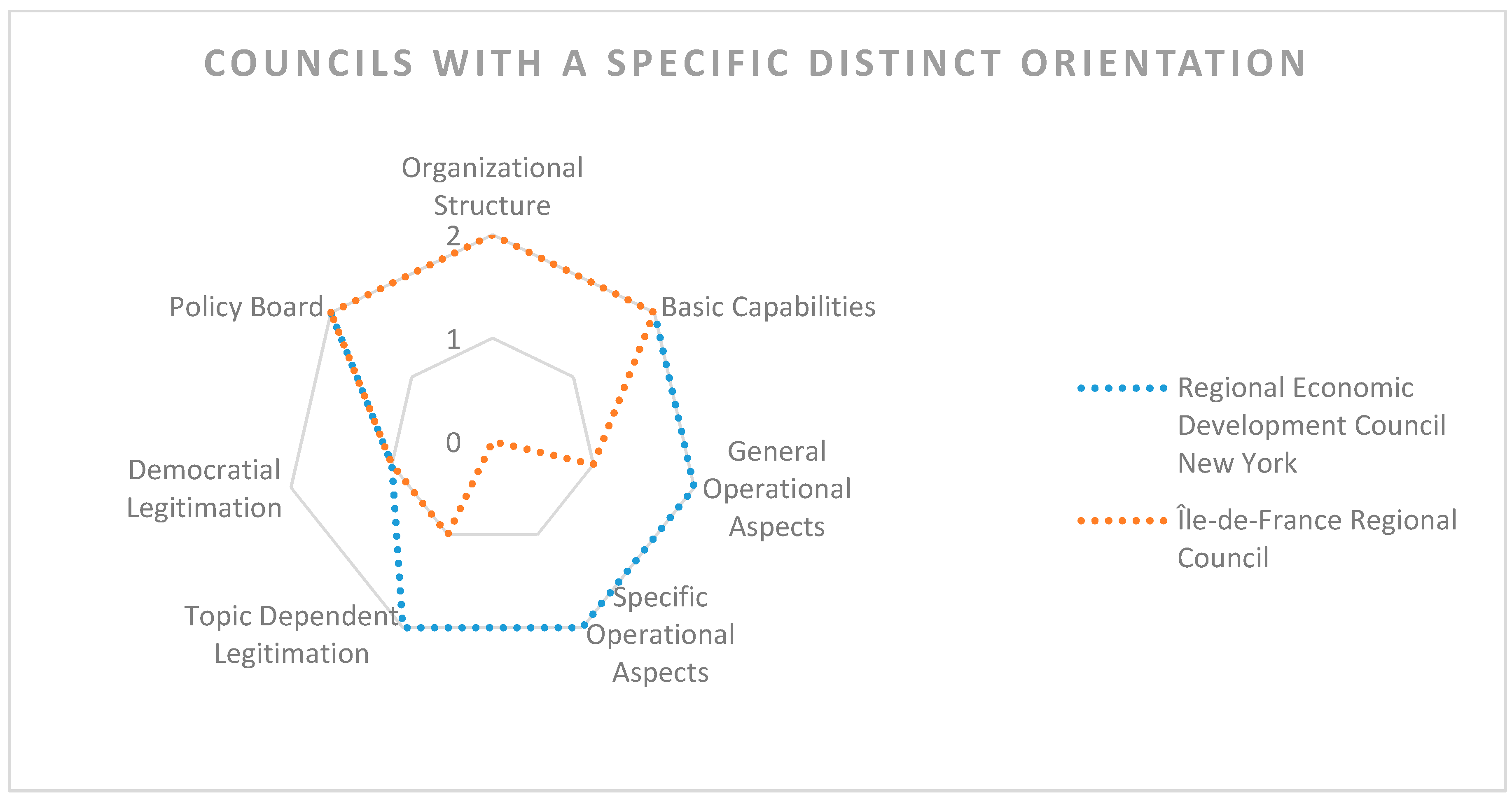

4.2. Regional Councils with a Specific Distinct Orientation

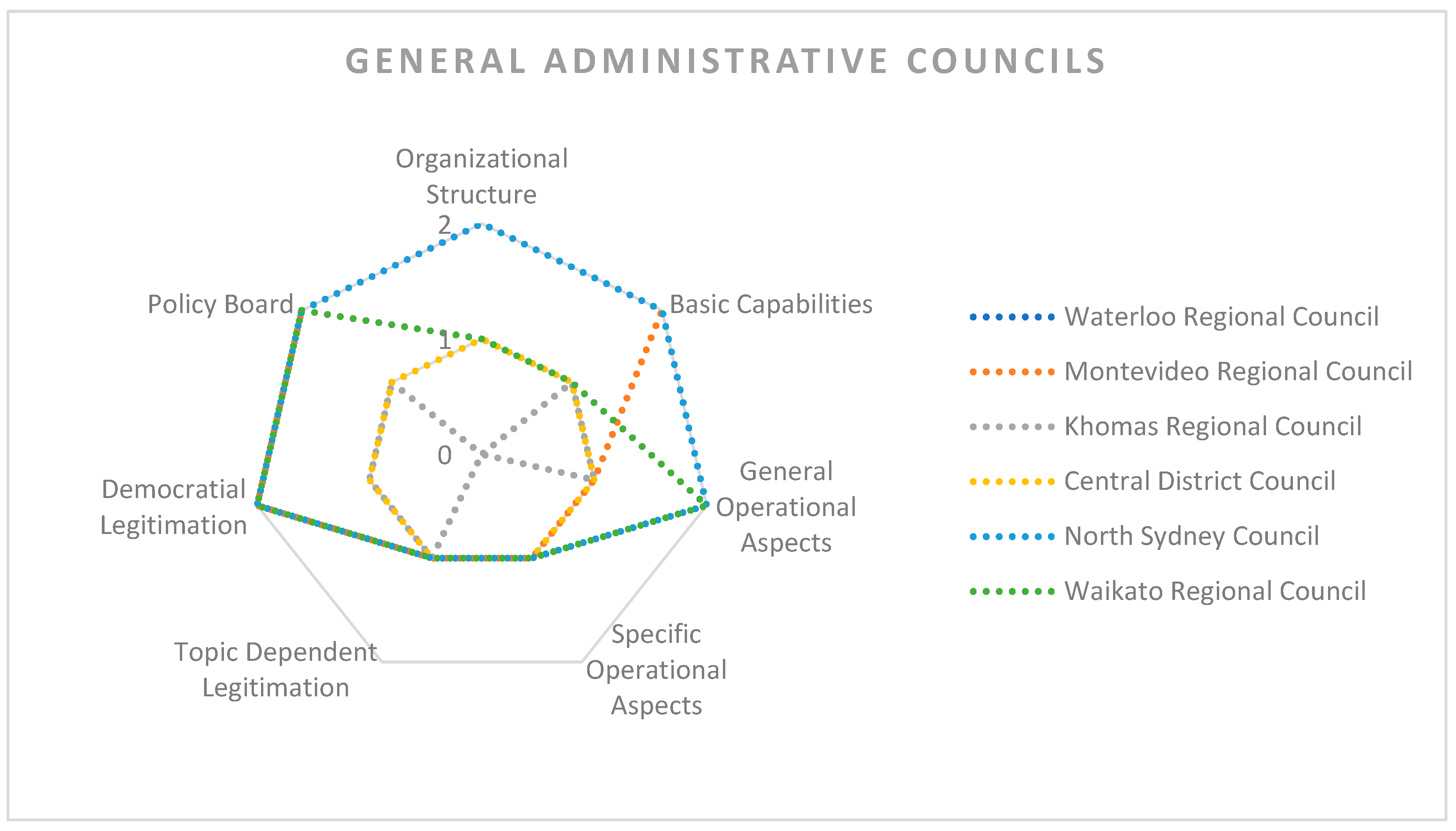

4.3. Regional Councils with General Administrative Functions

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects, the 2014 Revision. Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/publications/files/wup2014-highlights.Pdf (accessed on 14 February 2019).

- Zimmermann, K.; Heinelt, H. Metropolitan Governance in Deutschland. Regieren in Ballungsräumen und neue Formen politischer Steuerung; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Portney, K.E. Taking Sustainable Cities Seriously. Economic Development, the Environment, and Quality of Life in American Cities, 2nd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Cities & Towns Towards Sustainability. Aalborg Charta: Charter of European Cities & Towns Towards Sustainability. Available online: http://www.sustainablecities.eu/fileadmin/repository/Aalborg_Charter/Aalborg_Charter_English.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- Jonas, A.E.G. City-regionalism: Questions of distribution and politics. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 36, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, A.E.G. City-Regionalism as a Contingent ‘Geopolitics of Capitalism’. Geopolitics 2013, 18, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growe, A. Where do KIBS workers work in Germany?: Shifting patterns of KIBS employment in metropoles, regiopoles and industrialised hinterlands. Erdkunde 2016, 70, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growe, A. Emerging polycentric city-regions in Germany. Regionalisation of economic activities in metropolitan regions. Erdkunde 2012, 66, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jurey, N. Local and Regional Governance Structures. J. Plan. Lit. 2013, 28, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.Y.; Lee, J.H. Making Sense of Metropolitan Regions: A Dimensional Approach to Regional Governance. Publius J. Fed. 2010, 41, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Hoyler, M. Governing the new metropolis. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2249–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growe, A.; Münter, A. Die Renaissance der großen Städte. Geogr. Rundsch. 2010, 62, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ziafati Bafarasat, A. Exploring new systems of regionalism: An English case study. Cities 2016, 50, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafarasat, A.Z.; Baker, M. Strategic spatial planning under regime governance and localism: Experiences from the North West of England. Town Plan. Rev. 2016, 87, 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Growe, A. From places to flows? Planning for the new ‘regional world’ in Germany. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2014, 21, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Growe, A. When regions collide: In what sense a new ‘regional problem’? Environ. Plann. A 2014, 46, 2332–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. Regions and the World Economy. The Coming Shape of Global Production, Competition, and Political Order; Repr. New as Paperback; Oxford Univ. Pr: Oxford, MI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J.; Agnew, J.; Soja, E.W.; Storper, M. Global City-Regions. In Global City-Regions: Trends, Theory, Policy; Repr.; Scott, A.J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blatter, J. From ‘spaces of place’ to ‘spaces of flows’? Territorial and functional governance in cross-border regions in Europe and North America. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, M. The New Regionalism in Western Europe. Territorial Restructuring and Political Change; Elgar: Cheltenham, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.; Paasi, A. Guest Editorial: Regional World(s): Advancing the Geography of Regions. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J. Configuring the New ‘Regional World’: On being Caught between Territory and Networks. Reg. Stud. 2012, 47, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J. Re-reading the new regionalism: A sympathetic critique. Space Polity 2006, 10, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growe, A.; Volgmann, K. Exploring Cosmopolitanity and Connectivity in The Polycentric German Urban System. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2016, 107, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münter, A.; Volgmann, K. The Metropolization and Regionalization of the Knowledge Economy in the Multi-Core Rhine-Ruhr Metropolitan Region. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 2542–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growe, A. Raummuster unterschiedlicher Wissensformen. Der Einfluss von Transaktionskosten auf Konzentrationsprozesse wissensintensiver Dienstleister im deutschen Städtesystem. Raumforsch Raumordn 2012, 70, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Mager, C.; Schmidt, N.; Kiese, N.; Growe, A. Conflicts about urban green spaces in metropolitan areas under conditions of climate change: A multidisciplinary analysis of stakeholders’ negotiations in planning processes. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.L. (Ed.) Megaregions. Planning for Global Competitiveness; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.L.; Lee, D.J.-H.; Meijers, E.; Welch, T. (Eds.) Megaregions, Prosperity and Sustainability. Spatial Planning for Future Prosperity and Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Growe, A. Knoten in Netzwerken Wissensintensiver Dienstleistungen. Eine Empirische Analyse des Polyzentralen Deutschen Städtesystems; Rohn: Detmold, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fricke, C. Metropolitan Regions as a Changing Policy Concept in a Comparative Perspective. Raumforsch Raumordn 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Hoyler, M. Megaregions: Foundations, frailties, futures. In Megaregions: Globalization’s New Urban Form? Harrison, J., Hoyler, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.-W.; Park, S.-C. Metropolitan Governance: How Regional Organizations Influence Interlocal Land Use Coordination. J. Urban Aff. 2016, 36, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D. The Rise of Territorial Governance in European Policy. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 22, 1368–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.F.; Bryan, T.K. Identifying the Capacities of Regional Councils of Government. State Local Gov. Rev. 2009, 41, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualini, E.; Fricke, C. ‘Who governs’ Berlin’s metropolitan region?: The strategic-relational construction of metropolitan scale in Berlin–Brandenburg’s economic development policies. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2018, 7, 239965441877654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, J.A. Voluntary Regional Councils and the New Regionalism. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2004, 24, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby, J.E. Regional governance and regional councils. Nat Civ. Rev 1996, 85, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, T.K.; Wolf, J.F. Soft Regionalism in Action: Examining Voluntary Regional Councils’ Structures, Processes and Programs. Public Organ. Rev. 2010, 10, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, J.A. Understanding Local Government Cooperation in Urban Regions. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2016, 32, 40–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinelt, H.; Zimmermann, K. ‘How Can We Explain Diversity in Metropolitan Governance within a Country?’ Some Reflections on Recent Developments in Germany. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2011, 35, 1175–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschatzky, K.; Uyarra, E.; Héraud, J.-A. Understandind the Multi-Level, Multi-Actor Governance of Regions for Developing New Policy Designs. Available online: http://www.prime-noe.org/conference-presentations,92.html (accessed on 11 March 2016).

- EU Committee of the Regions. Governance of Metropolitan Regions. European and Global Experiences; Workshop on the “Governance of Metropolitan Regions in Federal Systems”: Brüssel, Belgium, 2011; Available online: http://espas.eu/orbis/sites/default/files/generated/document/en/Consolidated%20version%20-%20Metropolitan%20Governance%20-%20final.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2015).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Regional Development Policies in OECD Countries; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zonneveld, W. In search of conceptual modernization: The new Dutch ‘national spatial strategy’. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2005, 20, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dühr, S. Illustrating spatial policies in Europe. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2003, 11, 929–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.K. Measuring the Effectiveness of Regional Governing Systems. A Comparative Study of City Regions in North America; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gualini, E. The rescaling of governance in Europe: New spatial and institutional rationales. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2006, 14, 881–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mose, I.; Jacuniak-Suda, M.; Fiedler, G. Regional Governance-Stile in Europa. Eine vergleichende Analyse von Steuerungsstilen ausgewählter LEADER-Netzwerke in Extremadura (Spanien), Warmińsko-Mazurskie (Polen) und Western Isles (Schottland). Raumforsch Raumordn 2014, 72, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, C. Spatial Governance across Borders Revisited: Organizational Forms and Spatial Planning in Metropolitan Cross-border Regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 23, 849–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatter, J. Metropolitan Governance in Deutschland: Normative, utilitaristische, kommunikative und dramaturgische Steuerungsansätze. Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 2005, 11, 119–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dühr, S.; Stead, D.; Zonneveld, W. The Europeanization of spatial planning through territorial cooperation. Plan. Pract. Res. 2007, 22, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balchin, P.N.; Sykora, L.; Bull, G.H. Regional Policy and Planning in Europe; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Blotevogel, H.H.; Danielzyk, R.; Münter, A. Spatial planning in Germany: Institutional inertia and new challenges. In Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe: A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Changes; Reimer, M., Getimis, P., Blotevogel, H.H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Weber, E.; Henckel, D. (Eds.) The Planning System and Planning Terms in Germany. A Glossary; Verl. der ARL: Hannover, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, A. Regional Governance mit organisatorischem Kern: Das Beispiel der Region Stuttgart. Inf. Zur Raumentwickl. 2003, 8, 505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, N.; Dollery, B.; Witherby, A. Regional organisations of councils (ROCS): The emergence of network governance in metropolitan and rural Australia? Australas. J. Reg. Stud. 2003, 9, 169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Söderbaum, F. Modes of Regional Governance in Africa: Neoliberalism, Sovereignty Boosting, and Shadow Networks. Glob. Gov. 2004, 10, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Aspect | Subcategories | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational Elements | Policy Board | Political and technical committees: Do they exist? Are they separated? |

| Organizational Structure | Organization of horizontal and vertical interaction processes: Who is included in interaction processes? How is the process organized? | |

| Basic Capabilities | In-house staff: Is staff available? Is administrative support provided by the available staff? Is technical support provided by the available staff? A stable source of funding: Is a stable source of funding given? Where does the funding come from (e.g., provided by other administrative levels or risen as tax or contribution by the region?) | |

| Legitimation | Democratic Legitimation | Election of councillors: How are the councillors elected? How long is the election period? Who elects the councillors? |

| Topic Dependent Legitimation | Is the work of the council legitimated by the topics the council is working on? Does the council: Aim for regional economic competitiveness? Reduce inter-regional disparities? Aim for an endogenous, balanced and sustainable development? Solve specific regional challenges? Complete regional planning processes? Undertake technical analyses that serve as regional knowledge resource? | |

| Operational Aspects | General Operational Aspects | Does the council work transparent and on behalf of the region? Does the council: Apply an all-region focus? Operate by transparent governance regulations? Follow a clear framework (visions, missions, processes)? |

| Specific Operational Aspects | Does the council foster work beyond the council and its embeddedness in governance structures? Does the council: Support network activities in the region? Support and apply citizen participation? |

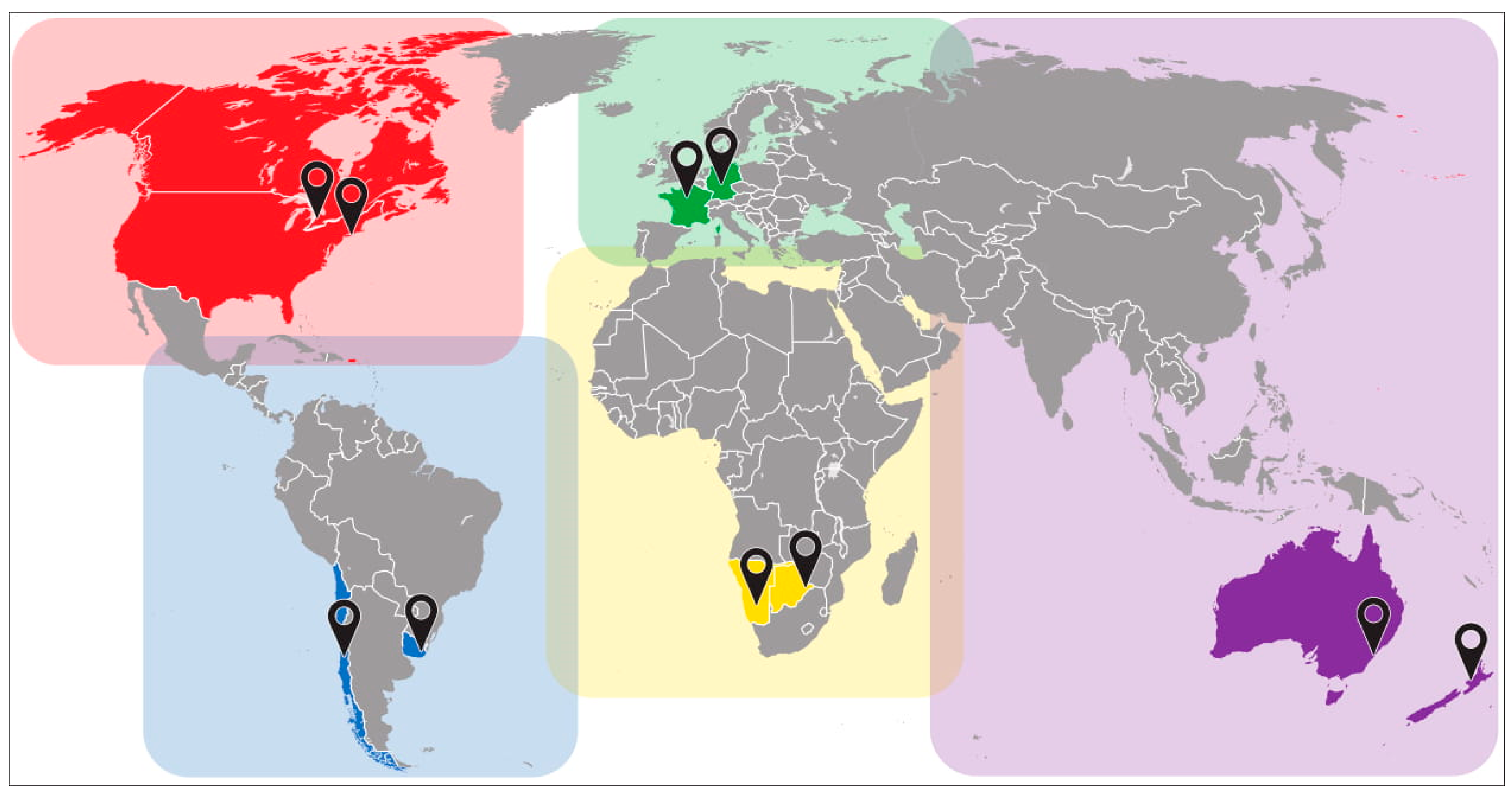

| Global Area | Nation State | Regional Council | Area Size | Inhabitants | Role of the Reg. Council |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | United States | Regional Economic Development Council New York | 54 mi² | 19,750,000 | Untypical, exceptional case, not regulated by the national state, dependent on private and non-profit associations and regulations of the State of New York. |

| Canada | Waterloo Regional Council | 26 mi² | 132,300 | Enabled by provincial legislation, carrying out legislative and executive functions. | |

| South America | Chile | Santiago Regional Council | 248 mi² | 6,158,080 | Regions as largest administrative unit. Regions in Chile are executors of central government. |

| Uruguay | Montevideo Regional Council | 633 mi² | 1,319,108 | Regions as second level of government in Uruguay with limited local self-government. | |

| Europe | Germany | Stuttgart Regional Council | 80 mi² | 597,939 | Strong position and strong legal framework of the regional level in Germany. |

| France | Île-de-France Regional Council | 47 mi² | 12,010,000 | Although a division into 26 regions in France exists, the legislative power of regions is very low. France is still governed within a centralized structure. | |

| Africa and Arabic Peninsular | Namibia | Khomas Regional Council | 142 mi² | 342,141 | Namibia is divided into 14 regional councils. The councils are enshrined in the constitution, but don’t have legal power. |

| Botswana | Central District Council | 57 mi² | 638,604 | Although the ’district’ level isn’t mentioned in the constitution, the level is present in Botswana and responsible for local administrative matters. | |

| Asia-Pacific | Australia | North Sydney Council | 4 mi² | 72,618 | The term ‘council’ is used in the Local Government Act to encompass all local governing bodies, recognising its common use to denote local government. |

| New Zealand | Waikato Regional Council | 25 mi² | 449,200 | Regional councils are common in New Zealand, however, their activities differ widely. |

| Country | Regional Council | Positive Response in form of |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | Waterloo Regional Council | Questionnaire |

| Uruguay | Montevideo Regional Council | Telephone interview |

| Germany | Stuttgart Regional Council | Telephone interview |

| France | Île-de-France Regional Council | Telephone interview |

| Botswana | Central District Council | Telephone interview |

| New Zealand | Waikato Regional Council | Telephone interview |

| Topic | Sample Questions |

|---|---|

| Questions dealing with organizational elements | Please describe the organizational aspects of your council in its current form. What is the best organizational aspect according to you? What changes would you recommend? |

| Questions dealing with the councils’ (topic-dependent) legitimation | What are the challenges facing your council? And how does the council contribute to solutions? Please tell us about a project or a plan that your regional council is proud of. Please tell us about a project or plan that didn’t go so well. What changes would you recommend assisting you facing these challenges? |

| Questions dealing with operational aspects | Does your council have a multi-level governance mechanism? Can you explain it? Does your council have the ability to shape public policy on a regional/national level? Does your council lobby on its behalf and for your region at the national level? Does the council interact with different players of the public sector, with stakeholders of the private sector or with NGOs? |

| Councils with a Distinctive Focus | Councils with Comprehensive Governance Functions | Councils with General Administrative Functions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational elements | To support the topic specific work of the councils, a stable source of funding and in-house staff is very important for this type of council. A differentiation between (political) decision making and administrative work is important as not all councils rely on democratic legitimation. | To support long-term comprehensive governance work, a stable source of funding and in-house staff is very important for this type of council. A differentiation between political decision making and administrative work is important to support democratically legitimized comprehensive governance mechanisms. | A differentiation between political decision making and administrative work is important to support a long-term orientated administrative work of the council. The dimension of potential funding sources and the number of in-house staff varies according the socio-economic situation of the respective nation states. |

| Legitimation | Democratic legitimation by elected councillors to govern the region is not the main focus. Legitimation develops through the topic dependent work to support the region. | Democratic legitimation by elected councillors to govern the region is important as the councils have the possibility to govern in the region. The topics covered are important to demonstrate how effective and important the council works. However, the topic dependent work does not have to legitimate the council. | Democratic legitimation by elected councillors to govern the region or by including elected councillors in decision-making processes is important to support the acceptance of the administrative work. |

| Operational aspects | The importance of operational aspects varies heavily. Symbolic councils do not necessarily carry out operational work. These role of these councils is to symbolize the regional level in a multi-level-system. For other councils, focussing on specific topics like economic development, the operational aspects are of high importance. | To support comprehensive governance functions, general operational aspects (like an all-region-focus and transparent governance regulations) are as important as specific governance functions that foster interaction beyond the regional council, e.g., with citizens and through network activities. | The emphasis on administrative functions leads to a focus on general operational aspects. Activities supporting operational structures and networks beyond the regional administrative structure are important but do not have the same importance as general operational aspects. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Growe, A.; Jemming, M. Regional Councils in a Global Context: Council Types and Council Elements. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3010022

Growe A, Jemming M. Regional Councils in a Global Context: Council Types and Council Elements. Urban Science. 2019; 3(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrowe, Anna, and Marilu Jemming. 2019. "Regional Councils in a Global Context: Council Types and Council Elements" Urban Science 3, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3010022

APA StyleGrowe, A., & Jemming, M. (2019). Regional Councils in a Global Context: Council Types and Council Elements. Urban Science, 3(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3010022