1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increase in violence against healthcare professionals, which is becoming a growing concern for the healthcare system and a public health issue [

1,

2]. Workplace violence refers to instances where professionals are abused, intimidated, or assaulted in the workplace or while traveling to and from work, posing a direct or implied threat to their safety, well-being, and overall health [

3,

4]. Violence may be physical, psychological, sexual, and racial [

5], with verbal abuse being the most common form of violence in the professional environment, usually perpetrated by patients and their families [

5,

6].

Violence towards healthcare professionals has an immediate impact on their daily lives and leaves sequelae, either through immediate local injury or through repercussions from the exercise involved in their profession [

7,

8]. In addition, violence can be associated with negative impacts on the physical or mental health of professionals in the short, medium, and long terms, namely increased levels of stress and anxiety, feelings of anger, guilt, insecurity, and burnout [

6,

9].

Guidelines to mitigate violence in the workplace have been discussed and presented, highlighting the importance of gathering data on the frequency, nature, causes, and consequences of violent incidents as a fundamental basis for effective public policies [

10,

11]. The absence of such data significantly compromises the ability of health managers and policymakers to develop appropriate preventive strategies and implement safety protocols based on scientific evidence. This information may contribute to the development of policies and coordinated plans to address violence against healthcare professionals. Improving safety and understanding the key predictors of workplace violence can have a significant impact on the quality of work performed by nurses and doctors in healthcare institutions [

12,

13], namely through the creation of policies, resources, and prevention programs to allow for the signalization and resolution of these situations.

Violence against healthcare professionals is an important public health problem worldwide, and, according to the most recent studies, the prevalence rate among healthcare professionals is 58.7%; considering the latest findings from a 2022 meta-analysis [

14], which are entirely in line with data from 2019, the prevalence rate is 61.9% [

15]. Another meta-analysis carried out in 2023 showed different prevalence rates depending on the type of violence, highlighting that 63.0% of healthcare professionals were victims of verbal violence [

16].

In Portugal, the recent literature supports that healthcare professionals are at higher risk of violence in the workplace when compared to other sectors, with one study reporting that only 23.81% formally reported the incident to the occupational health department [

17]. Since 2012, an increasing trend in violence reports was registered [

18], from 593 cases in 2017 to 995 in 2019, highlighting the need for a national-level approach to addressing this type of violence and guidelines for prevention and systematic notification. Since, in Portugal, notification is spontaneous, and healthcare professionals are often reluctant to report violent incidents [

17], a representative picture of the country’s reality is missing.

To understand the factors associated with this type of workplace violence, we reviewed the literature, which showed that younger, less experienced, and female healthcare professionals, especially nurses, are at increased risk of workplace violence [

13,

19,

20]. On the other hand, we also understand that aggressors often have underlying mental health disorders, are under the influence of substances, or are experiencing significant personal stressors [

13,

19,

21]. All of these factors are crucial to developing targeted interventions to protect healthcare workers and ensuring a safer working environment.

It is also known that the lack of human resources, excessive workloads, and the continuous emotional management of patients and family members are factors that may be associated with the development of various occupational diseases related to stress, anxiety, depression [

22], and workplace violence. However, the impact and costs of violence against healthcare professionals extend beyond the individual, affecting their families, communities, the broader social and economic environment, and, ultimately, the quality of care they provide [

6,

23,

24]. It is crucial to implement preventive interventions that target high-risk indicators and establish a true safety culture for patients and professionals through well-coordinated and comprehensive leadership that protects the health, safety, and well-being of healthcare professionals.

Considering that, in Portugal, violence against healthcare professionals continues to go undocumented at the national level, this leaves a critical knowledge gap that significantly hinders the development of effective public policies and evidence-based institutional interventions. This lack of national data represents a fundamental obstacle for policymakers in implementing appropriate preventive strategies, specific safety protocols, and appropriate legislative measures. National data from the Directorate-General for Health (DGS) and other studies described in [

18] suggest that violence against healthcare professionals is a persistent problem, but it lacks the national representativeness and analytical depth necessary to guide effective public policies.

A study on predictors of workplace violence in hospital and primary care settings conducted in Portugal [

25] involved 276 healthcare professionals, of whom 59.1% were nurses, 16.3% were physicians, 13.0% were healthcare assistants, and only 11.6% were administrative staff. This imbalance clearly highlights the underrepresentation of roles such as emergency responders, administrative staff, and technicians.

We believe that this knowledge gap warrants a new and comprehensive study, based on a robust methodological approach, that estimates the nature, frequency, and main factors associated with violence against healthcare professionals (doctors and nurses) in different healthcare settings. This study has direct policy relevance, as it provides an essential empirical basis to guide policymakers in formulating specific legislation, developing national occupational safety guidelines, and implementing evidence-based prevention programs.

This study will offer a much-needed evidence base to guide decision-makers in implementing stronger institutional policies, improving workplace safety protocols, and fostering a safer environment for healthcare professionals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

With the intent to estimate the nature, frequency, and main factors associated with violence against healthcare professionals (doctors and nurses) in healthcare settings, a quantitative, descriptive and cross-sectional study, based on Portuguese healthcare professionals was implemented.

2.2. Participant Recruitment

Between January and May 2024, a convenience sample of healthcare professionals was assembled. All physicians and nurses working at 4 differentiated public healthcare institutions located in the south of Portugal were eligible to be integrated into this study and were invited to participate, via their institutional e-mail, for a total of 3525 healthcare professionals. Among those, 440 completed the questionnaire (proportion of participation: 12.5%). This low response rate is an important methodological limitation that may affect the representativeness of the results and introduce significant selection biases. We consider this sample to be representative of the population, with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5% calculation using the online calculator (

https://comentto.com/es/calculadora-muestral/, accessed on 16 August 2024), although low adherence limits the generalization of results to the entire population of Portuguese healthcare professionals.

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

Data was collected through an online platform using a structured questionnaire, specifically created for the study, on healthcare professionals’ sociodemographic (sex, age, nationality, and marital status) and work-related characteristics (professional category, workplace, type of contract, working time at the institution and work shifts) and aspects related to violence towards healthcare professionals in the workplace (

Table S1). The questionnaire was developed based on a review of the literature, following the guidelines of the Portuguese Directorate-General for Health [

18,

26], and included 54 items divided into seven sections: (1) characterization of the participant, (2) characterization of the situation of violence, (3) reporting on the situation of violence, (4) non-reporting on the situation of violence, (5) information about the aggressor, (6) procedures at the level of the healthcare institution/healthcare unit in response to an episode of violence, and (7) violence observed.

Section (1), the characterization of the participant, was organized to collect personal information, namely age, sex, gender identity, marital status, nationality, professional group, place of work, employment relationship, number of years in service, shift work, knowledge of action plans regarding violence in the workplace and procedures in the event of exposure, knowledge of reporting a situation of violence, and whether they had been a victim of violence in the workplace.

The items included in Section (2) relate to the characterization of the situation of violence suffered, namely the frequency of episodes of violence—including a block where participants could choose the type of violence they suffered—the consequences of the act of violence suffered, the time and day of the week when the act of violence occurred, and finally whether the participant reported the situation of violence. The prevalence of workplace violence was defined as ever being a victim of violence at work. Four types of violence were considered: psychological, physical, sexual, and others. For each type, participants were asked to select the forms of workplace violence applicable to their experience. Regarding the most common forms of psychological violence, different behaviors were presented, namely “moral harassment”, “threats”, “death threats”, “insults (offenses, insults)”, “coercion (blackmail, intimidation, humiliation)”, “isolation/kidnapping”, “stalking”, and “no form of this type of violence”. To assess the main practices of physical violence, the following options were given: “pushes”, “kicks”, “slaps”, “throwing objects”, “twists”, “burns”, “beating”, “strangulation”, “stabbing”, “hair pulling”, “damage to property of the institution”, “damage to private/individual property”, and “no form of this type of violence”. Sexual violence forms included the following options: “sexual abuse”, “sexual harassment”, “sexual coercion”, “exhibitionism”, “violation”, and “no form of this type of violence”. Finally, other options of violence allowed for the selection of “gender violence against women”, “gender violence against men”, “discrimination by sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and sexual characteristics”, “racial/ethnic discrimination”, “other type of discrimination”, and “no form of this type of violence” (

Table S1).

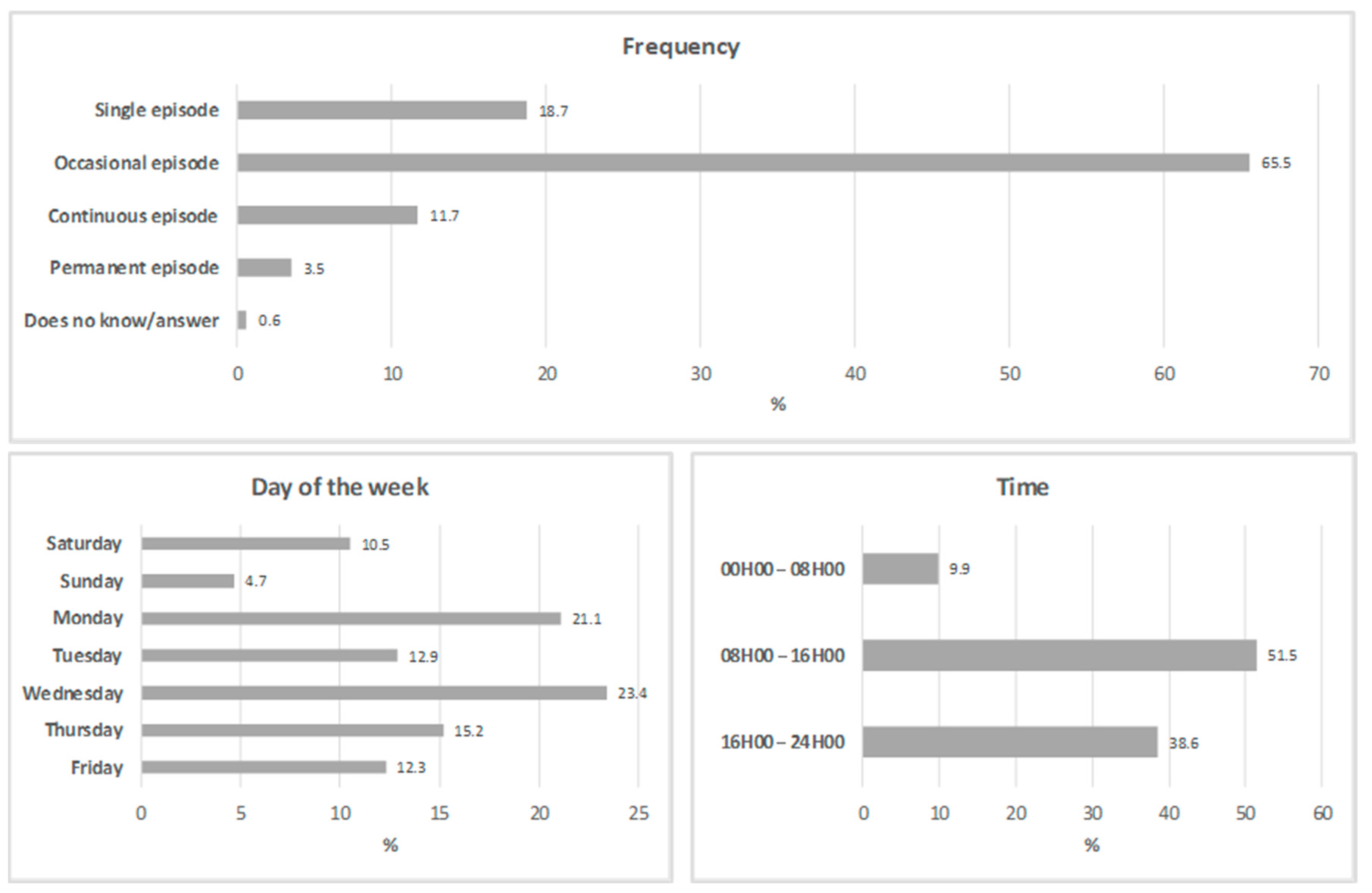

Data on the frequency and schedule of workplace violence towards healthcare professionals was also collected. The incident frequency was inquired using previously defined categories: single episode, occasional episode, continuous episode, permanent episode, and did not know/answer. The day of the week in which the violent episode occurred was registered, as well as the time, comprising 3 categories: from midnight to 8 am; from 8 am to 4 pm; and from 4 pm to midnight (

Table S1).

In Section (3), there were items for the participant to describe where they reported the situation of violence and, in Section (4), the reason or reasons for not having reported the situation of violence.

In Section (5), there were items where the healthcare professionals reported the main sociodemographic characteristics of the aggressors, namely sex, age, nationality, the aggressor’s relation to the health institution, and the consequences of the episode of violence.

People who access healthcare services were considered as patients or users, while those accompanying them were referred to as patient/user companions. Citizen groups were defined as civic organizations of individuals who come together to work for the betterment of their community (

Table S1).

Section (6) includes items relating to the procedures carried out by the institution in response to the episode of violence, particularly whether any procedures were carried out to investigate the causes of the episode of violence and what measures were taken. Finally, in Section (7) recorded the violence observed, the characterization of the victim and the aggressor, and the consequences of this act of violence.

The “validation” of the questionnaire was carried out on a sample of 15 participants and consisted of legitimizing the content, clarity, and comprehensibility, as well as semantic and cultural validation. We ensured that there was no need to make any changes and continued with the application [

27]. In the data analysis, it was found that the data was reliable and usable for analysis.

2.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 29.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics, namely frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations (SD), were calculated. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of continuous variables, confirming that age followed a normal distribution.

Table 1 describe the participants’ main characteristics.

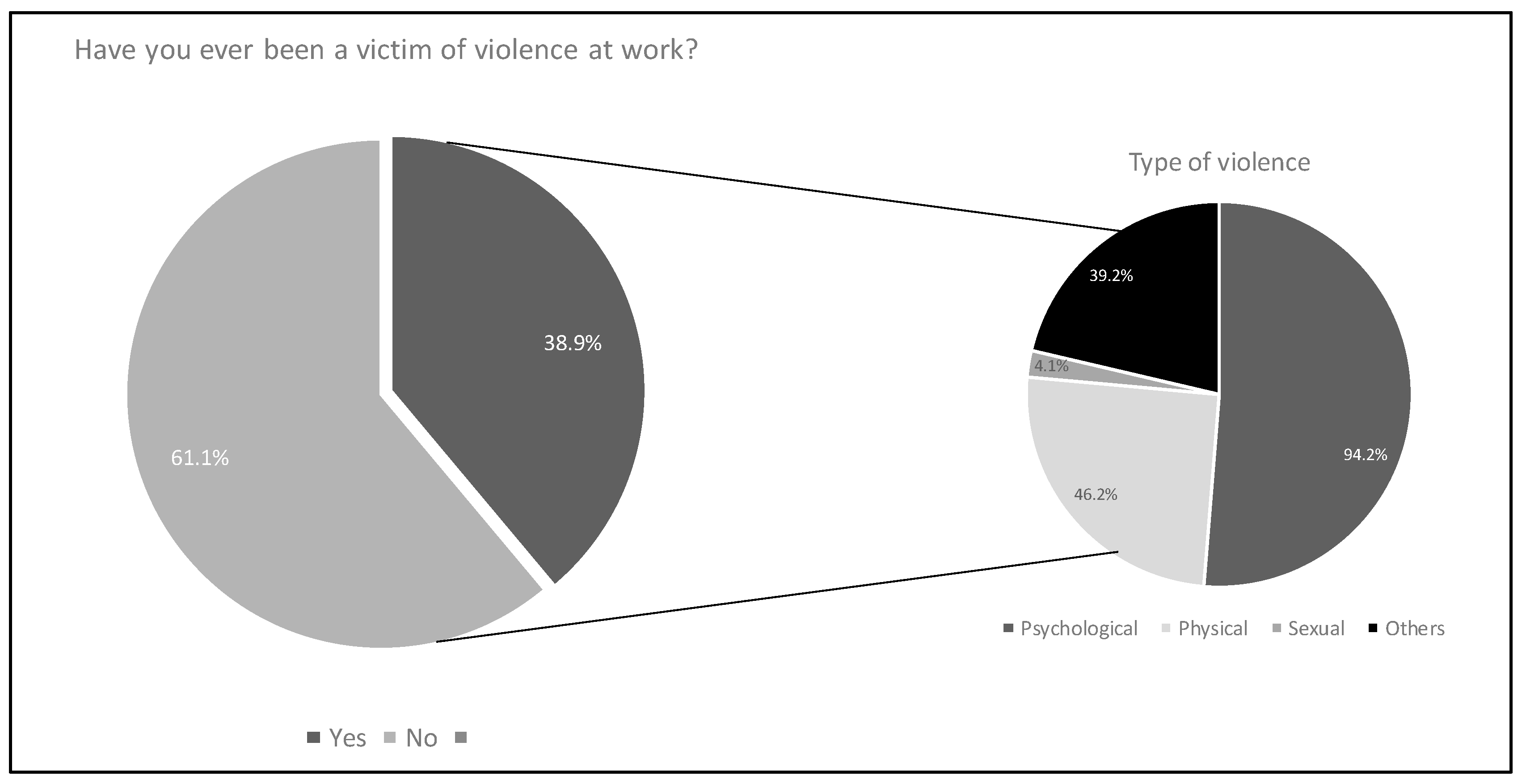

The prevalence of workplace violence towards healthcare professionals was displayed in a pie chart, as well as the distribution of violence by type. The most common forms of workplace violence towards healthcare professionals, according to type of violence, were described as proportions.

Unconditional logistic regression models were fitted to compute crude odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) for assessing the association between the sociodemographic and work-related characteristics of the healthcare professionals and violence at work. The dependent variable in the logistic regression models was having ever experienced workplace violence (yes vs. no), as self-reported by participants in the questionnaire. Age was categorized into three groups (23–33; 34–55; ≥56 years) to reflect early-career, mid-career, and late-career stages of healthcare professionals, based on common cutoffs in the literature and the distribution of the sample. An odds ratio equal to 1 indicates no association between the healthcare professionals’ characteristics and workplace violence. If the odds ratio is less than 1, it suggests a protective effect, meaning that the sociodemographic and work-related characteristics of healthcare professionals are associated with lower odds of violence at work. Conversely, an odds ratio greater than 1 indicates that the exposure is associated with a risk factor, which means that the healthcare professionals’ characteristics are associated with higher odds of workplace violence. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, considering the absence of value 1 on the 95%CI.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study is part of the project “Violence against Health Professionals in the Alentejo Region”, funded by the “CHRC Research Grant 2022”, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Évora (no. 22187). The necessary authorizations to carry out the study were also granted by the ethics committees of each of the institutions involved. To ensure the protection of the participants, all anonymity and confidentiality measures were implemented. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants according to the World Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

4. Discussion

This article is the second in a sequence of publications presenting the findings of our research. In the first article, we discussed knowledge, reporting, and consequences of violence against healthcare professionals [

27]. In this study, we investigated the prevalence, nature, and factors associated with violence against healthcare professionals in southern Portugal, revealing alarming data on the occurrence of violence in the workplace, with 38.9% of participants reporting having been victims of some kind of aggression. These results have direct implications for public occupational health policies, highlighting the urgent need for systemic interventions by policymakers and health managers. These findings are in line with international studies that show a growing trend in violence in the health sector, especially in care units with high patient demand.

Workplace violence among Portuguese healthcare professionals is a complex issue that stresses the need for additional rigorous analytical and interventional research, although the results of this study should be interpreted by taking into account the methodological limitations identified, particularly the low response rate (12.5%), which may affect the representativeness of the findings. A high prevalence of violence towards healthcare professionals was described in our study, especially psychological violence such as injuries, threats, and psychological coercion. The results of this study corroborate the findings of previous research that highlights the high prevalence of violence against healthcare professionals, particularly nurses working in the psychiatric area [

28].

Such incidents were mostly occasional, occurring during the daytime and weekdays. The statistical association described between younger ages, a longer period working in the same institution, and working in shifts emphasizes the importance of organizational support that recognizes the problem, and therefore develops and implements appropriate and effective strategies to address it.

Overall, almost 40% of healthcare professionals experienced at least one type of workplace violence. Previous studies, such as Li et al. [

29], describe a highly variable prevalence of workplace physical violence, ranging from 2.75% in Thailand to 88.31% in the United Kingdom. A recent umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses found that overall violence prevalence among healthcare workers was reported to be as high as 78.9%, a prevalence exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic [

28]. The variability in the estimates worldwide may be due to the methodological heterogeneity observed across the studies, namely regarding the various and often interchangeable definitions of workplace violence actions [

30], resulting in a heterogeneous assessment of workplace violence, and the different perceptions of violence across different cultures [

31,

32]. This methodological inconsistency poses a significant challenge for policymakers, who need standardized data to develop effective legislation and public policies. Thus, it is important to establish a set of definitions for workplace violence in the health sector, as this can serve as a starting point for accurately identifying and addressing workplace violence, despite the need to adjust or expand them in the future to reflect changes in the workplace [

30]. Such standardization is essential to guide the formulation of evidence-based public policies and consistent national guidelines.

In Portugal, a previous study carried out amongst healthcare workers in Lisbon described a prevalence of any type of violence of 36.8% in a public hospital and 60% in a primary healthcare center [

33]. These results emphasize the need to access both primary and secondary care settings, simultaneously. The previous literature suggests that proximity to the population, higher accessibility, long-term doctor–patient relationships, as well as the high demand for timely responses and the greater isolation of this sector, make it particularly susceptible to episodes of violence [

34]. Although our data include primary and secondary healthcare settings, the relatively small sample size and low response rate prevent a robust comparison between the two settings, which is a major limitation of this study. Therefore, future studies should consider stratification by healthcare settings with more representative samples.

The literature frequently supports verbal abuse as one of the most frequent forms of workplace violence against healthcare workers [

35,

36], as described in our study. Additionally, research shows that individuals who have been subjected to multiple types of workplace violence tend to experience poorer working conditions, increased risk of burnout, lower sleep quality, and a stronger desire to leave their jobs [

37]. Studies corroborate that workplace violence contributes to nurses’ burnout, negatively affecting patient safety [

38]. Therefore, it is essential to acknowledge this issue and enhance workplace security. In Portugal, a previous study carried out among healthcare workers in a public hospital concluded that only 23.8% of victims notified the incident to the occupational health department [

17], underscoring the challenging path ahead. Under-reporting is also mentioned in other studies, mainly due to the perception of lengthy processes and lack of legal support [

36]. Under-reporting is also due to fear of victimization, discouragement from employers, and the perception that reporting will have no consequences [

39].

The factors statistically associated with exposure to violence were younger age, higher duration of employment at the same institution, and shift work. Young nurses may have less experience and fewer skills to take appropriate safety measures to prevent violence and deal with it, which may explain the higher prevalence among this group [

40]. Also, those who work in shifts and for a longer period in the same place may have a higher workload and, therefore, little tolerance to patients and their relatives’ questions and doubts [

41]. However, the cross-sectional design of the study prevents the establishment of causal relationships, and longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these associations. Thus, healthcare institutions should prioritize education and training regarding the management and prevention of workplace violence, as well as the development of support measures to improve nurses’ well-being. It is essential that these institutional measures are supported by comprehensive public policies and adequate funding to ensure their effective implementation.

Male patients and their relatives were the main perpetrators of violence against healthcare professionals, in line with the previous literature [

6]. Non-compliance with procedures, communication, and dissatisfaction are among the factors most associated with violence against healthcare professionals [

36].

Weak communication between healthcare professionals and patients, frequently associated with the lack of human resources [

34], emphasizes the need to invest in health literacy to empower the population to take responsibility for their own health and reduce the demand for healthcare. This issue requires coordinated policy interventions, including public investment in human resources for the health sector and national health literacy programs.

Violence in the workplace is indeed a global problem [

36]. The difficulty in finding internationally recognized instruments and the need to use standardized instruments in order to enable comparability of data in different contexts are highlighted. This standardization is essential to support policymakers in developing effective legislation and public policies based on robust scientific evidence. Recognizing this phenomenon as a serious problem can contribute to the implementation of local and international strategies, contributing to a healthier workplace and, consequently, improving the care provided [

28]. On the other hand, the findings demonstrate the need to improve reporting systems, since reporting episodes of violence is also stressful for the victims [

38].

A systematic review of the literature reinforces the need to improve the management of human resources and the development of strategies to prevent and manage violence, taking into account its effects on the mental health of professionals [

1].

Legislation on violence against healthcare professionals in the workplace is still insufficient, as is the institutional support provided, and greater legislative commitment and anti-discrimination policies are a priority [

39]. Despite the methodological limitations identified, the results of this study provide important preliminary evidence that can guide policymakers in formulating specific legislation, developing funding programs for preventive measures, and creating national systems for monitoring and responding to violent incidents against healthcare professionals.

Limitations of the Study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the only Portuguese study addressing the prevalence, nature, and main determinants of violence towards healthcare professionals in the last 20 years. However, we recognize important methodological limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. The low response rate (12.5%) represents a significant limitation that may compromise the representativeness of the sample and introduce substantial selection biases. This low participation rate may indicate that the professionals most affected by violence avoided participating, or, conversely, that only those with specific experiences responded, considerably limiting the generalizability of our results to the entire population of Portuguese healthcare professionals.

In addition, the underrepresentation of some professional categories is another relevant methodological limitation, since different professional categories may have different patterns of exposure to violence. The cross-sectional design of this study prevents the establishment of causal relationships, only allowing for the identification of associations between variables. Future studies should use larger and more representative samples of entire healthcare settings workforces and also explore additional mediators and mechanisms to develop effective strategies for healthcare managers and policymakers [

42]. Another relevant limitation of this study is the absence of specific questions about episodes of violence perpetrated through social networks, as it does not explicitly mention digital violence or violence that takes place on online platforms. We recognize, however, that violence on social media has an increasing impact on people’s lives and can significantly affect healthcare professionals. We therefore suggest that future research consider including this type of violence. Also, further cross-country and cultural research are essential in order to capture broader, diverse, and representative experiences, allowing for comparisons and providing quality support to healthcare workers, adjusted to different realities, needs, and cultural backgrounds.

To increase participation and improve representativeness in future studies, different methodological strategies can be implemented, recognizing that low adherence constitutes a significant methodological challenge in research on occupational violence, as will presenting the project to all employees in advance and conducting face-to-face interviews where participants have more time and a more suitable context to reflect about workplace violence [

43]. Additionally, the human resources department could give incentives such as presenting feedback of results, helping to motivate employees to participate [

44,

45], and developing a self-reflection culture regarding workplace violence. At the same time, it is crucial to pay special attention to workers who have already been victims of workplace violence, since they can be absent from work due to the incident itself or the physical and/or psychological consequences of the incident. Thus, the “healthy worker effect” [

46] may be contributing to underestimate the prevalence described in our study. Also, the cross-sectional nature of our study impairs a robust conclusion regarding the causal association between healthcare workers’ sociodemographic and work-related characteristics and workplace violence.

Despite these significant methodological limitations, which must be taken into account when interpreting and applying the results, this study provides important and pioneering information on workplace violence against Portuguese healthcare professionals, and the results should be interpreted within the context of these limitations. It is an important first step towards tackling this problem and improving the safety and well-being of healthcare workers. Therefore, further longitudinal research is needed, with larger sample sizes and more robust methods of data collection. Data and information related to violent incidents must be comprehensively gathered to understand the full extent of the problem and develop prevention strategies based on potentially changeable risk factors to minimize the negative effects of workplace violence [

9,

37].

Contributions to Practice, Academia, and Policy

Our results provide important information about workplace violence in the healthcare sector, offering direct practical applications for healthcare institutions, policymakers, and frontline professionals, highlighting the urgent need to implement evidence-based prevention and protection strategies for healthcare professionals. The results have immediate policy implications and can guide the formulation of specific legislation on occupational safety in healthcare settings and the creation of national guidelines for the prevention of workplace violence. The high prevalence of psychological violence (94.2%) and the significant proportion of physical violence (46.2%) indicate an urgent need for institutional interventions based on the associated factors identified, including, for example, training and prevention programs; workplace policies and reporting mechanisms that are more user friendly; security and staffing measures during peak hours; and mental health and support services to mitigate the impact of this violence against healthcare professionals.

Since 30% of aggressors were colleagues (nurses and doctors), this highlights the need for better conflict-resolution training and interprofessional teamwork initiatives to foster a safer work environment.

The results directly support the formulation of evidence-based policies that specifically address violence against healthcare professionals, providing essential data to ensure compliance with national and international workplace safety standards. This study offers concrete support for policymakers to develop specific regulations, funding programs for preventive measures, and mandatory protocols for reporting and responding to violent incidents.

This study contributes to the broader theoretical understanding of the violence at workplace against healthcare professionals by reinforcing and extending existing frameworks on occupational health, workplace aggression, and associated factors in high-stress environments. The results emphasize that violence is not random, but is associated with structural and systemic factors such as shift work, tenure, and age. This aligns with theoretical perspectives on organizational stress and job demand control models in healthcare environments. Previous theories have often focused on patient-related aggression. This study demonstrates that a considerable percentage of aggressors are colleagues, suggesting that workplace culture and internal professional dynamics play a critical role, and also highlights the intersectionality of occupational risks in healthcare.

5. Conclusions

Considering the methodological limitations of this study, particularly the low response rate (12.5%) and the cross-sectional design which prevents causal inferences, the results suggest that, in Portugal, workplace violence against healthcare professionals is a reality that deserves urgent attention, and these conclusions should be interpreted within the context of the identified limitations. Although the generalization of the results is limited by the representativeness of the sample, the data collected provide important indications about the need for institutional and policy solutions.

The possible consequences of this situation include a significant negative impact on the physical and mental health of healthcare professionals, which may be associated with absenteeism, staff turnover, and a potential decrease in the quality of care provided. These results have direct implications for the formulation of public occupational health policies, as they highlight the need for systemic interventions that go beyond isolated institutional measures. The Portuguese Constitution states that “everyone has the right to the protection of health and the duty to defend and promote it” [

47], and these rights and duties also extend to healthcare professionals, as ordinary citizens, requiring the state to implement specific public policies to ensure safe working environments in the healthcare sector.

We believe that there needs to be greater recognition of workplace violence as a public health problem, and this will require a systemic and coordinated approach between different levels of government, health institutions, and professional organizations. This recognition should be translated into specific public policies, including appropriate legislation, funding for preventive programs, and the creation of national monitoring and response systems. Health institutions should also implement measures based on the associated factors identified in this study to prevent violence and support affected workers, recognizing that these institutional measures should be complemented by comprehensive national policies. In this regard, we highlight the need for further longitudinal research to better understand the associated factors and temporal relationships between variables related to workplace violence in the health sector, as the cross-sectional design of the present study only allows for the identification of associations, not causal relationships.

This research bridges the gap between theory and practice, providing empirical evidence that informs both workplace policies and theoretical models of occupational violence, while always considering the methodological limitations identified. Its conclusions, within the limitations of the study, underscore the importance of institutional interventions coordinated with public policies, evidence-based safety measures, and comprehensive policy frameworks to protect healthcare professionals from violence. These interventions have the potential to improve workplace safety and, consequently, the quality of care provided to patients, constituting a priority for public health.

As recommendations, we highlight the need to develop specific legislation on the prevention of violence against healthcare professionals, based on scientific evidence; implement standardized national guidelines for responding to violent incidents; implement training programs for healthcare professionals on violence prevention and management; improve communication between healthcare professionals and users; increase staffing and resources in healthcare institutions; develop public policies to prevent violence in the workplace; develop longitudinal studies with more representative samples to establish causal relationships between associated factors and violence at work; conduct transnational research to enable comparisons and external validation of results; and include analyses of digital violence and cyberbullying against healthcare professionals.