A Compact Heat Sink Compatible with a Ka-Band Gyro-TWT with Non-Superconducting Magnets

Abstract

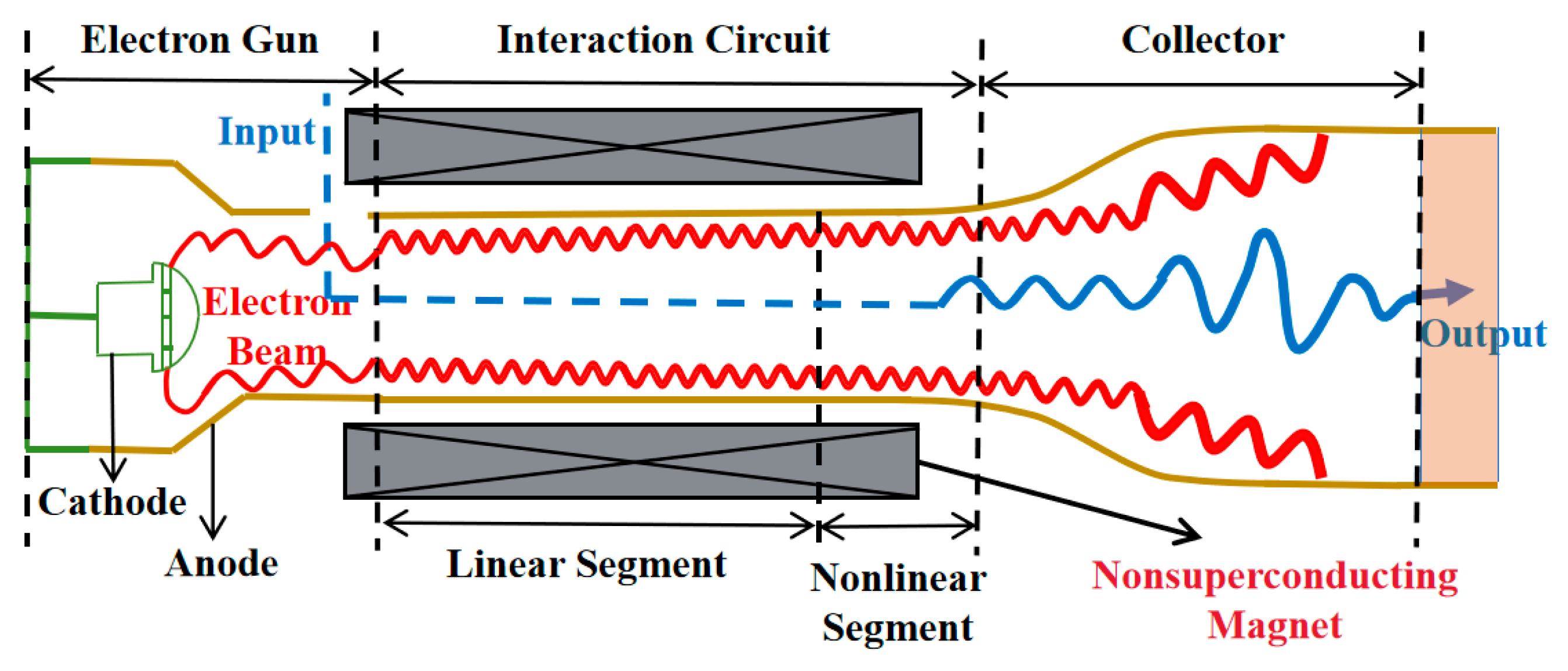

1. Introduction

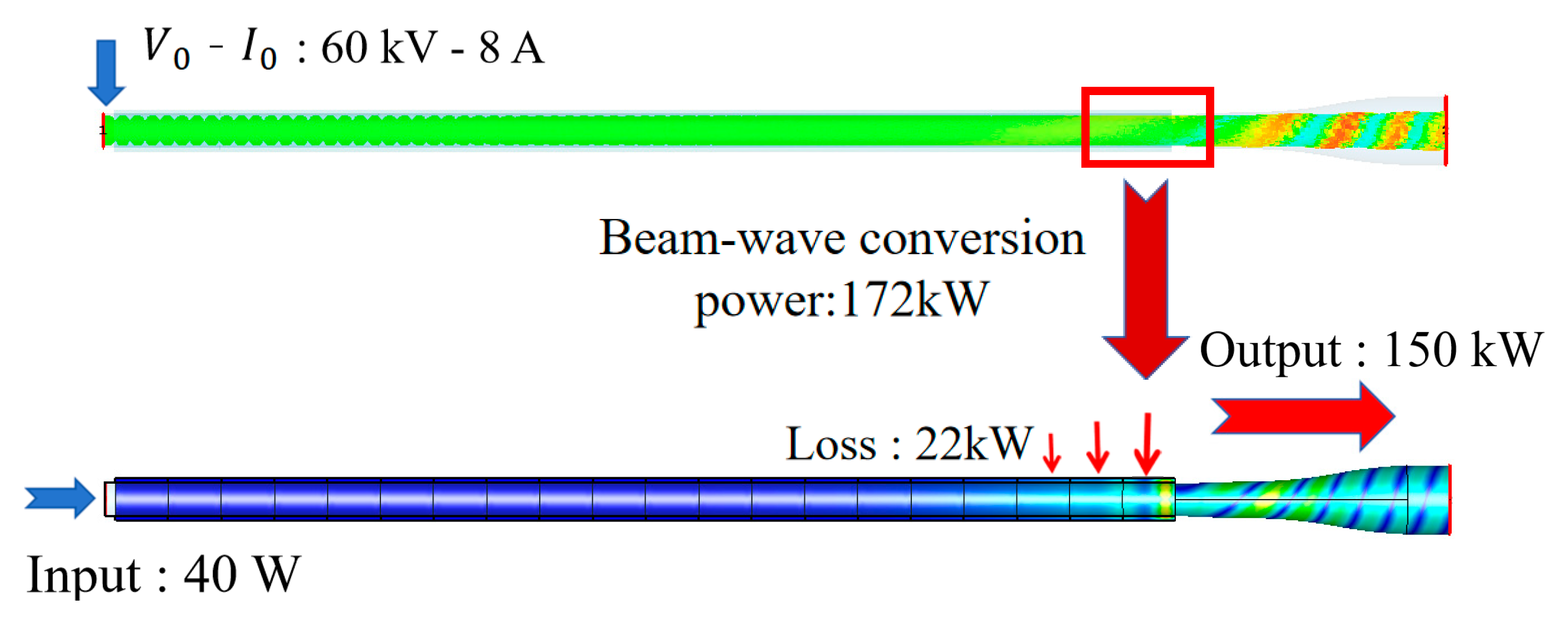

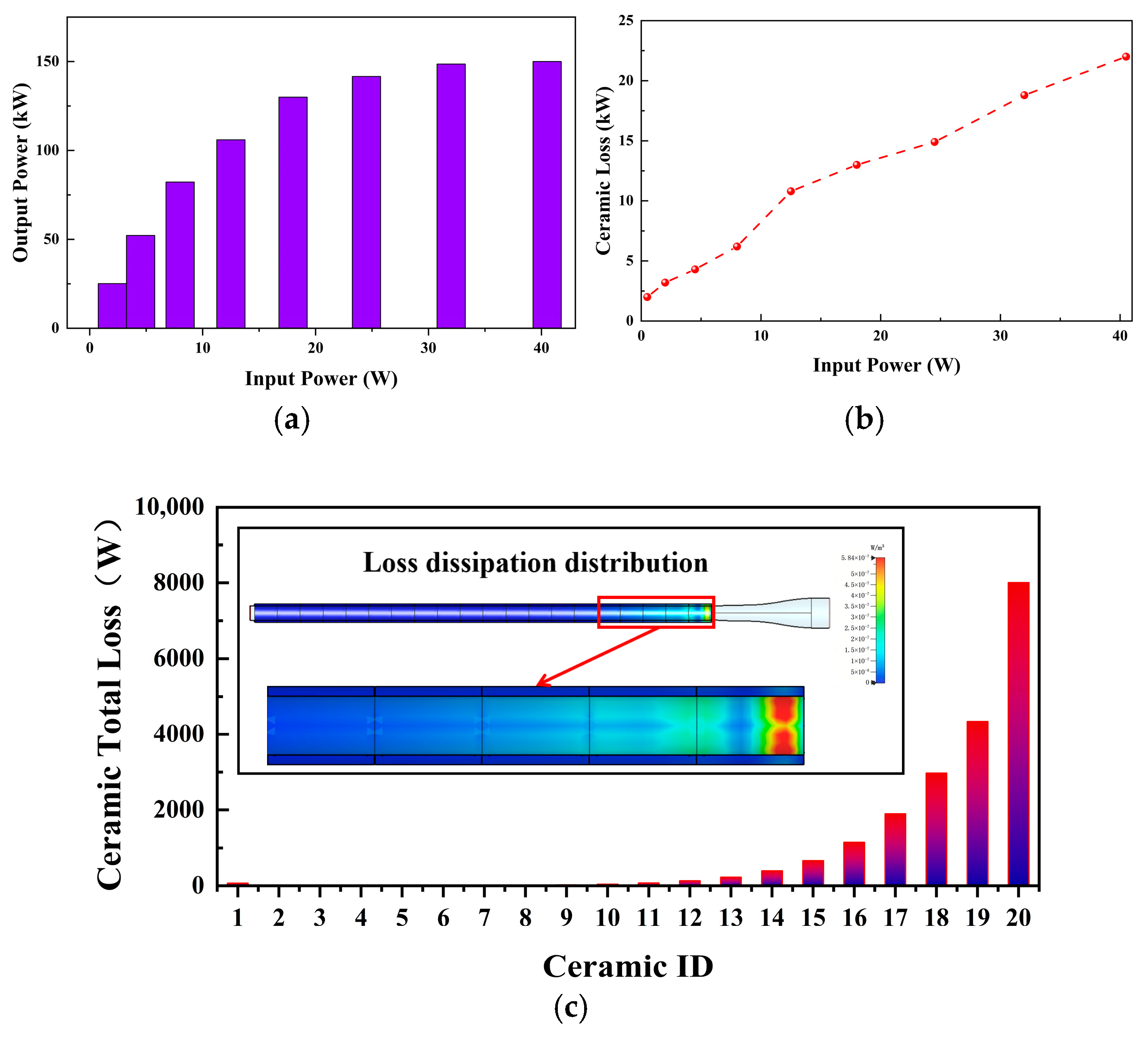

2. Analysis of Heat Source

3. Joint Microwave–Thermal Management Evaluation Model

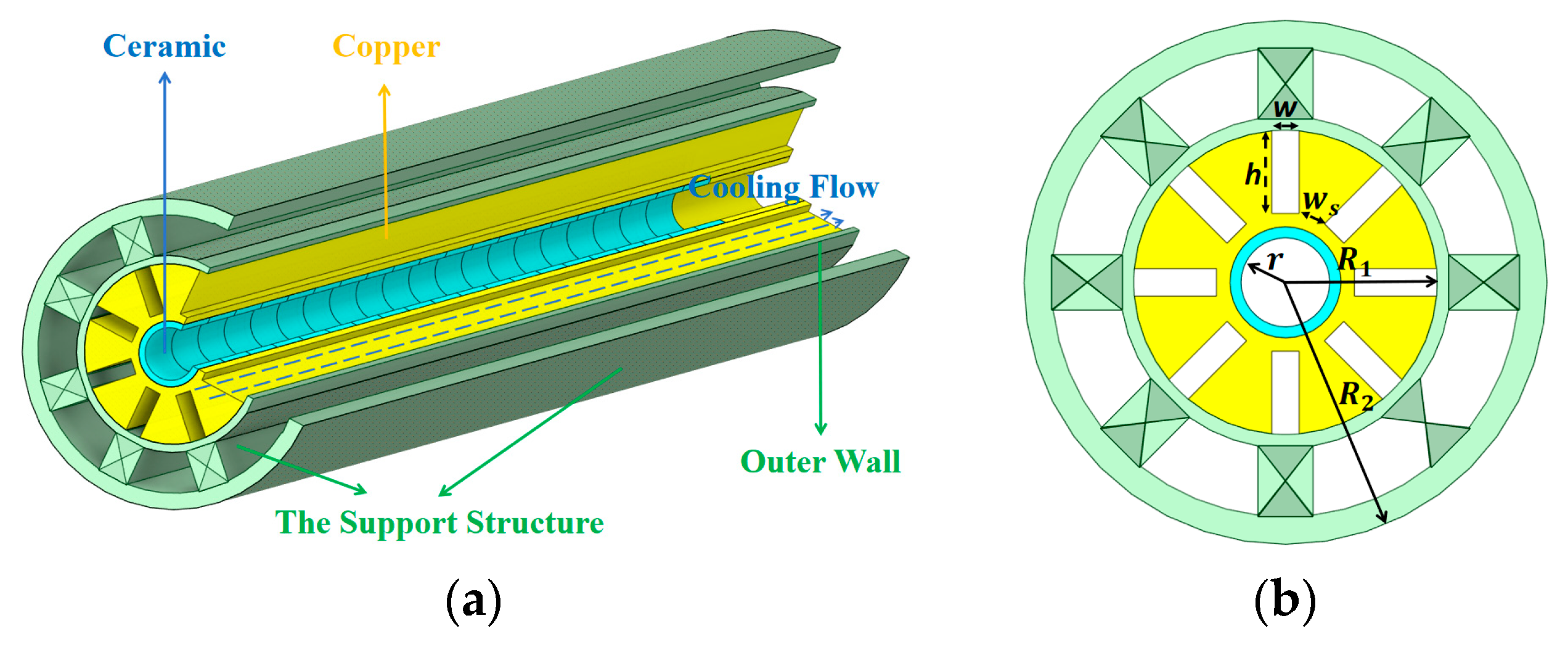

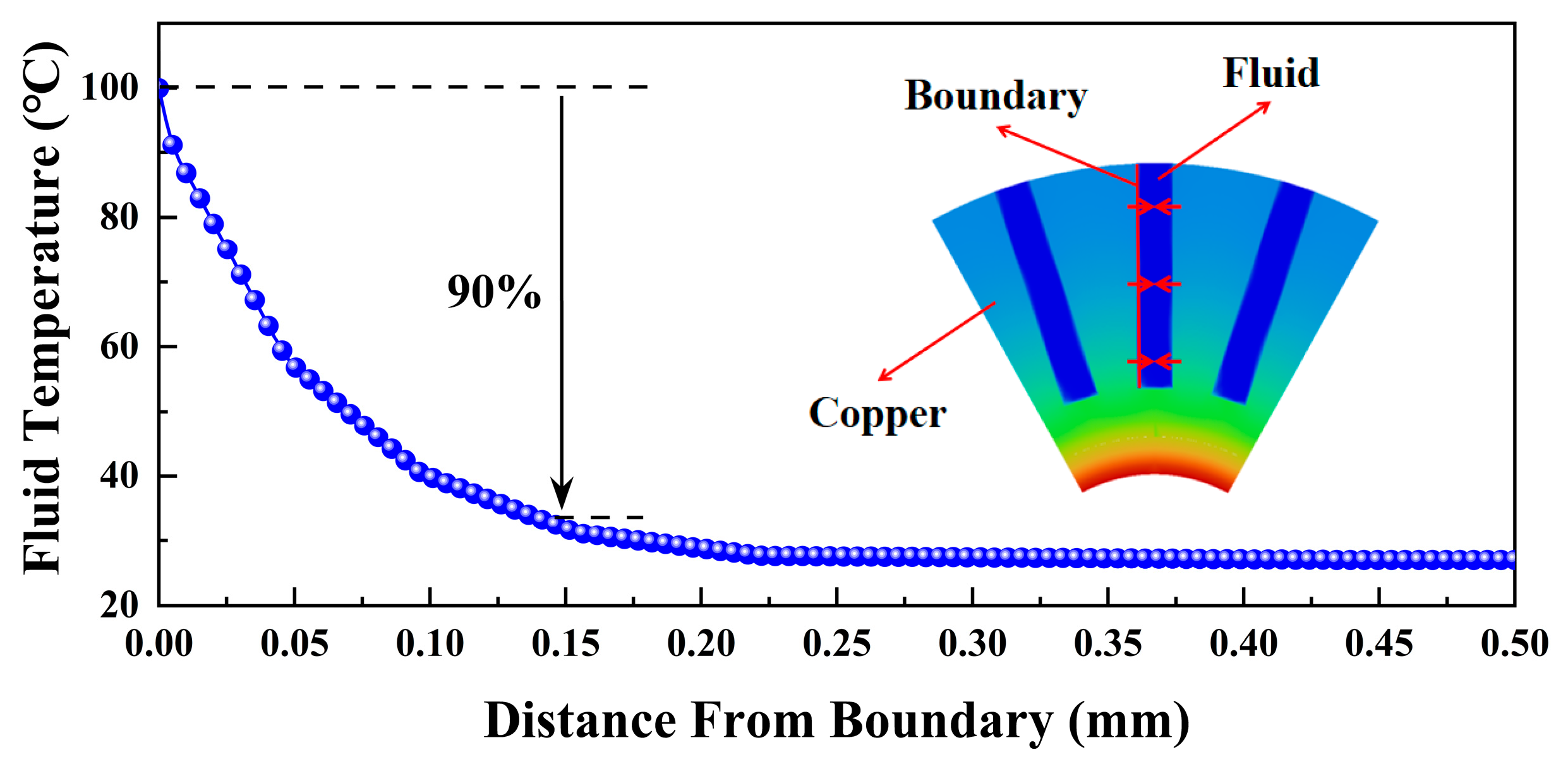

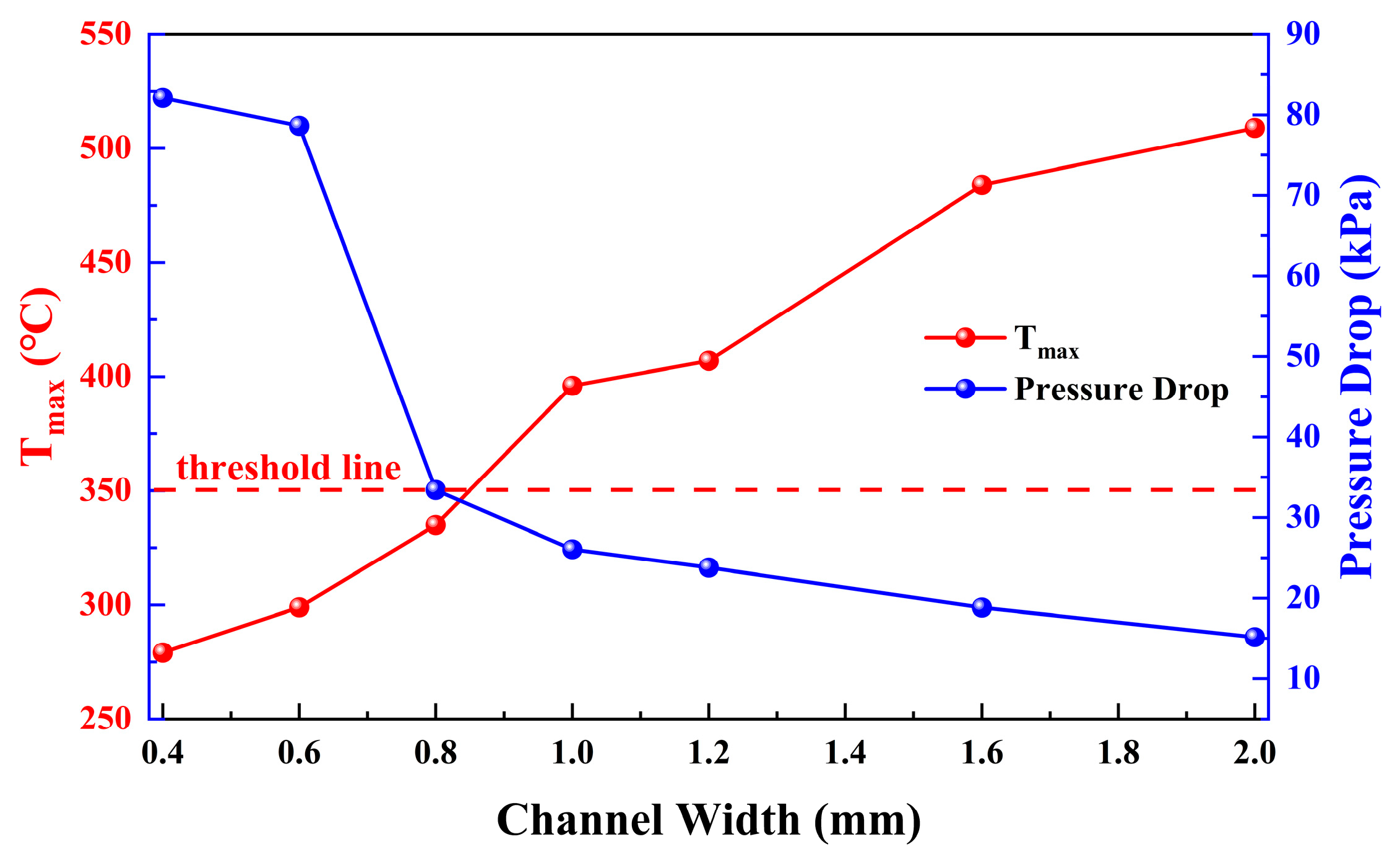

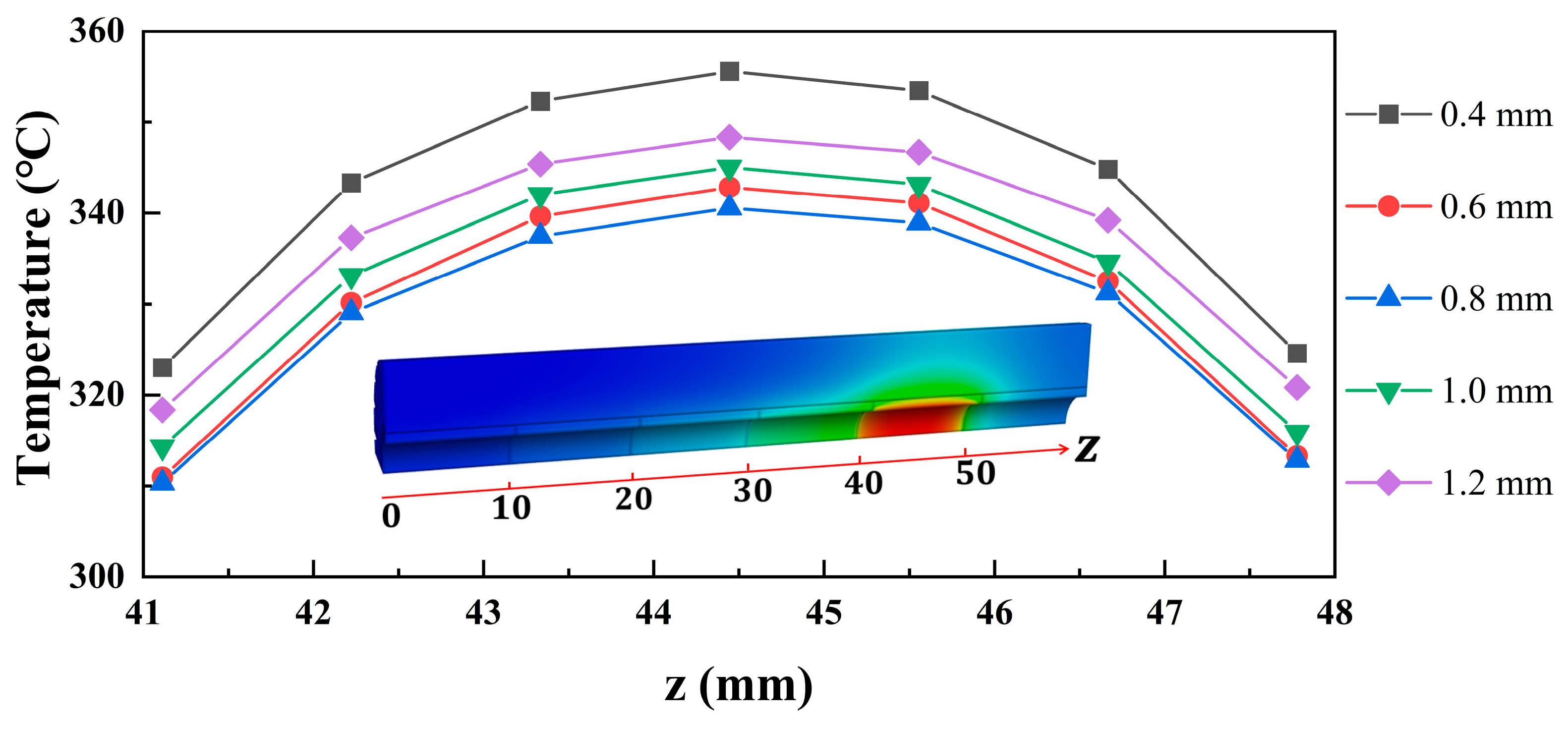

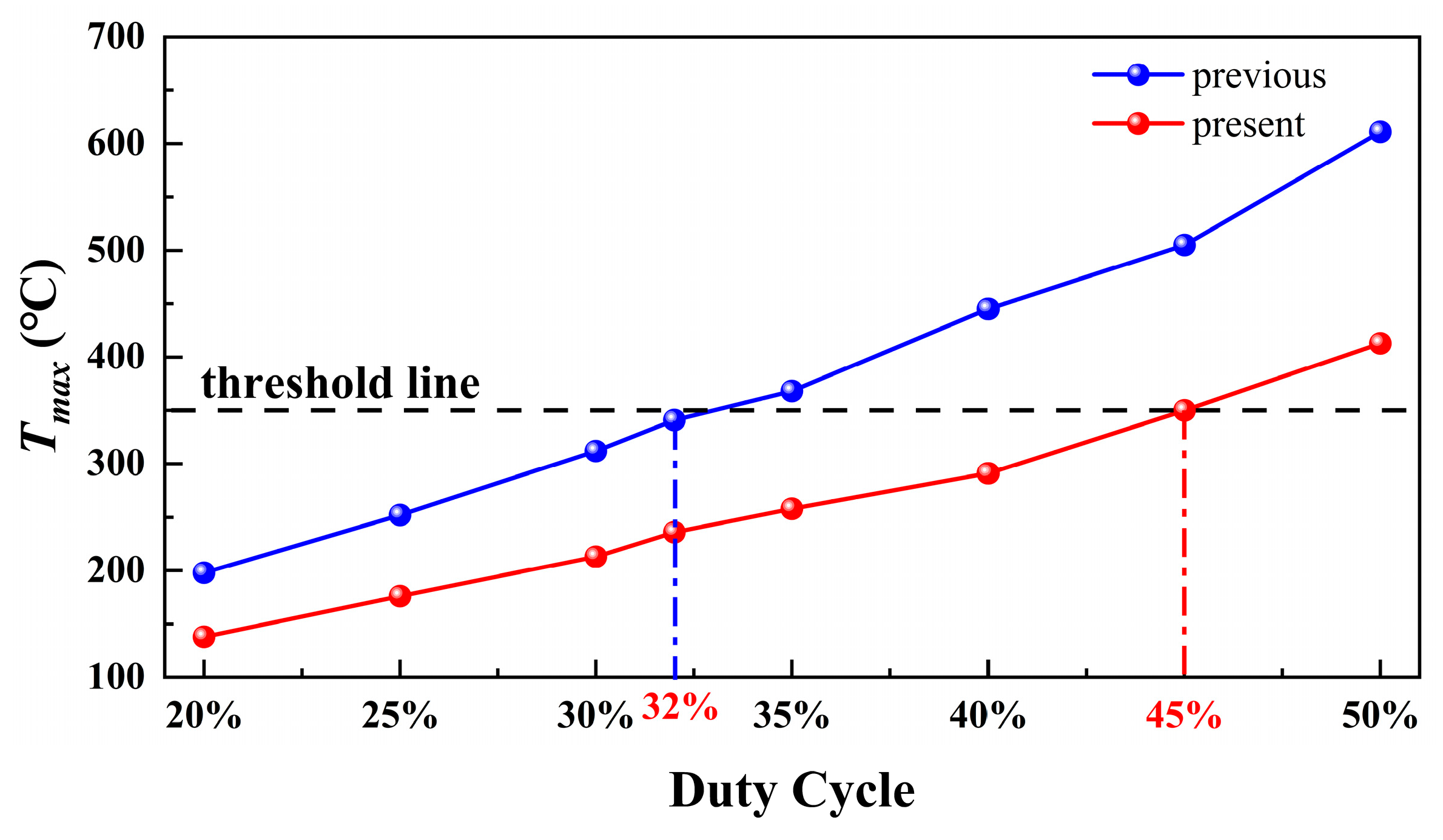

3.1. Suitable Channel Structure for High Coolant Utilization

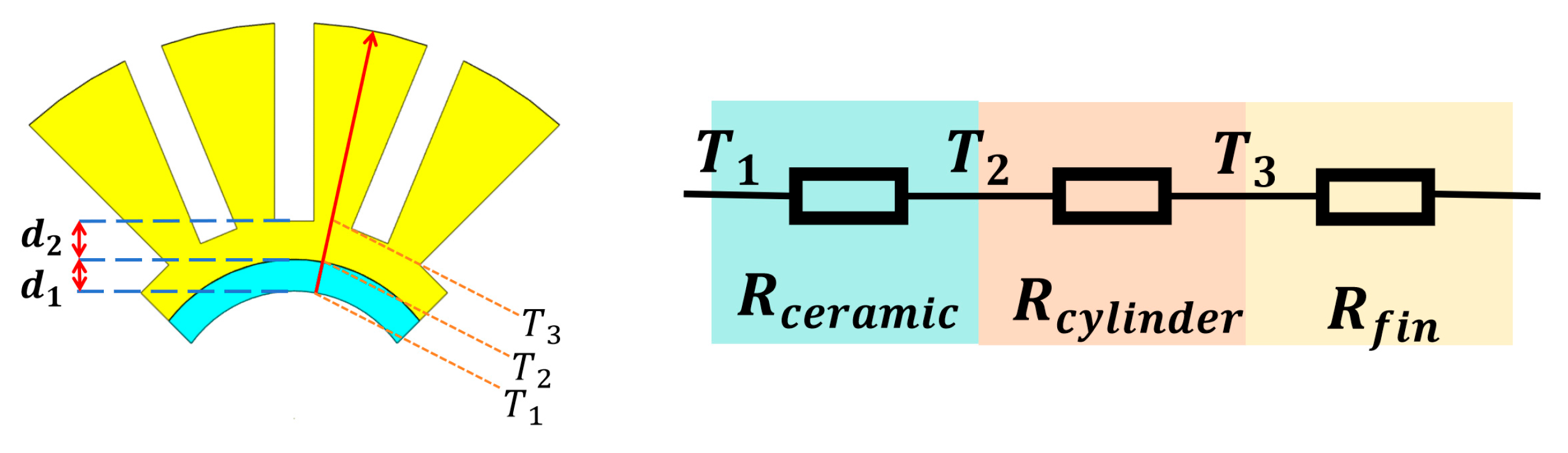

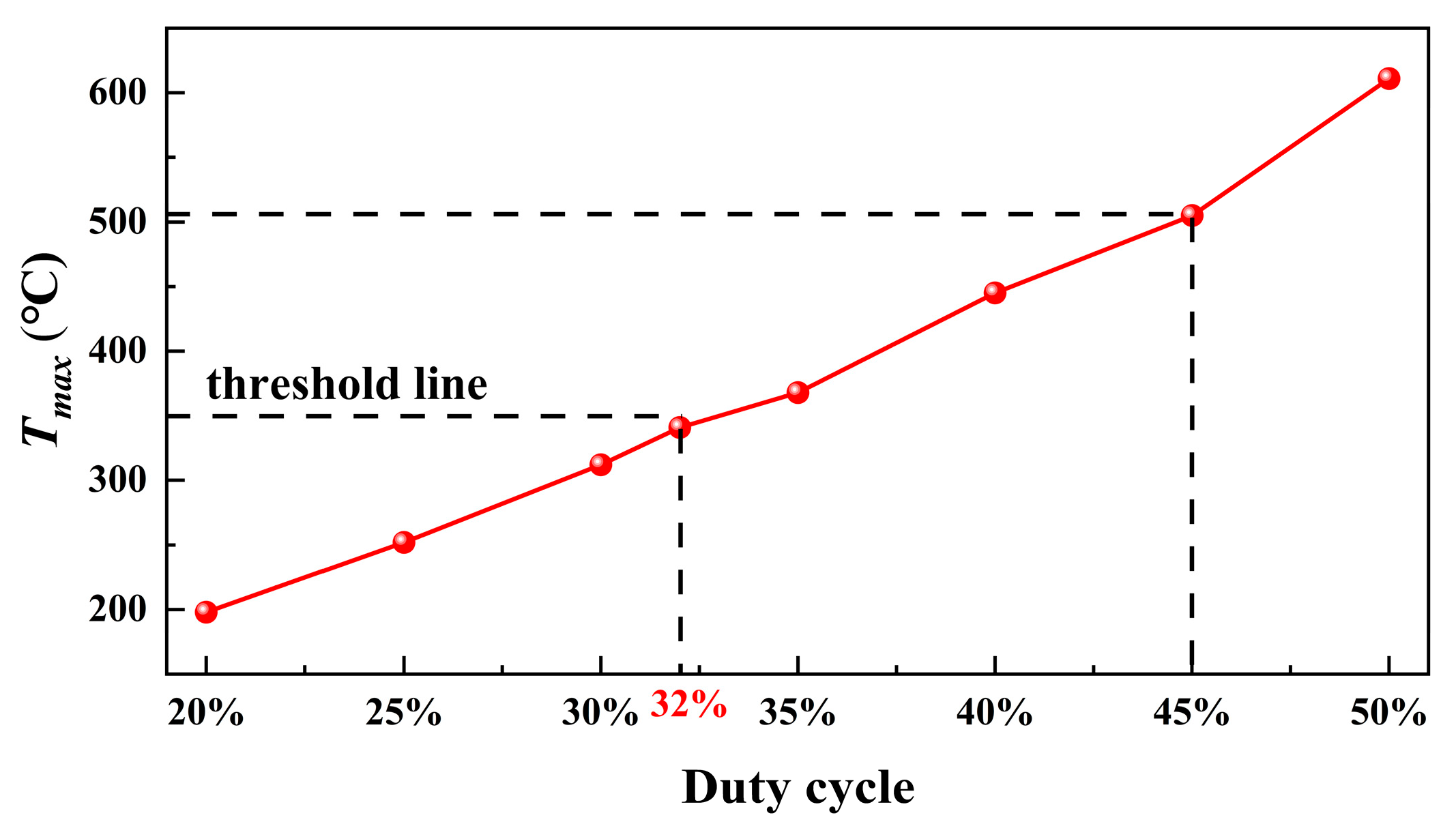

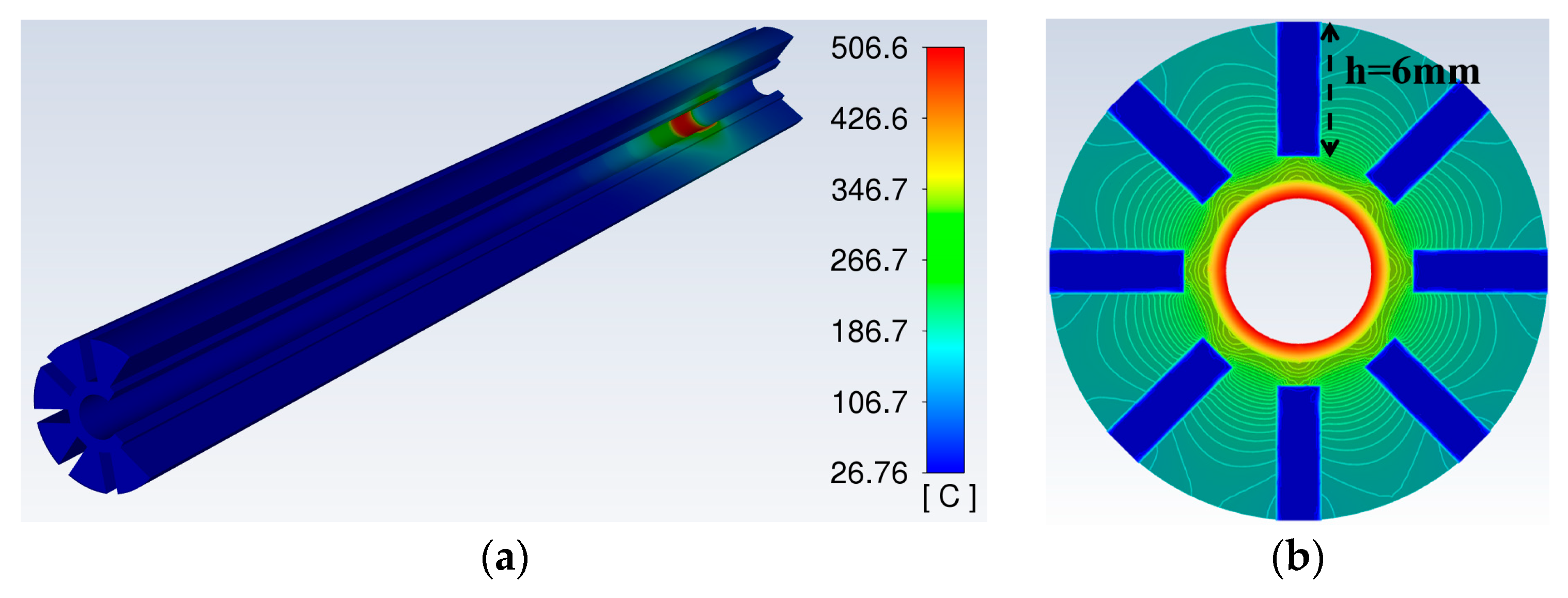

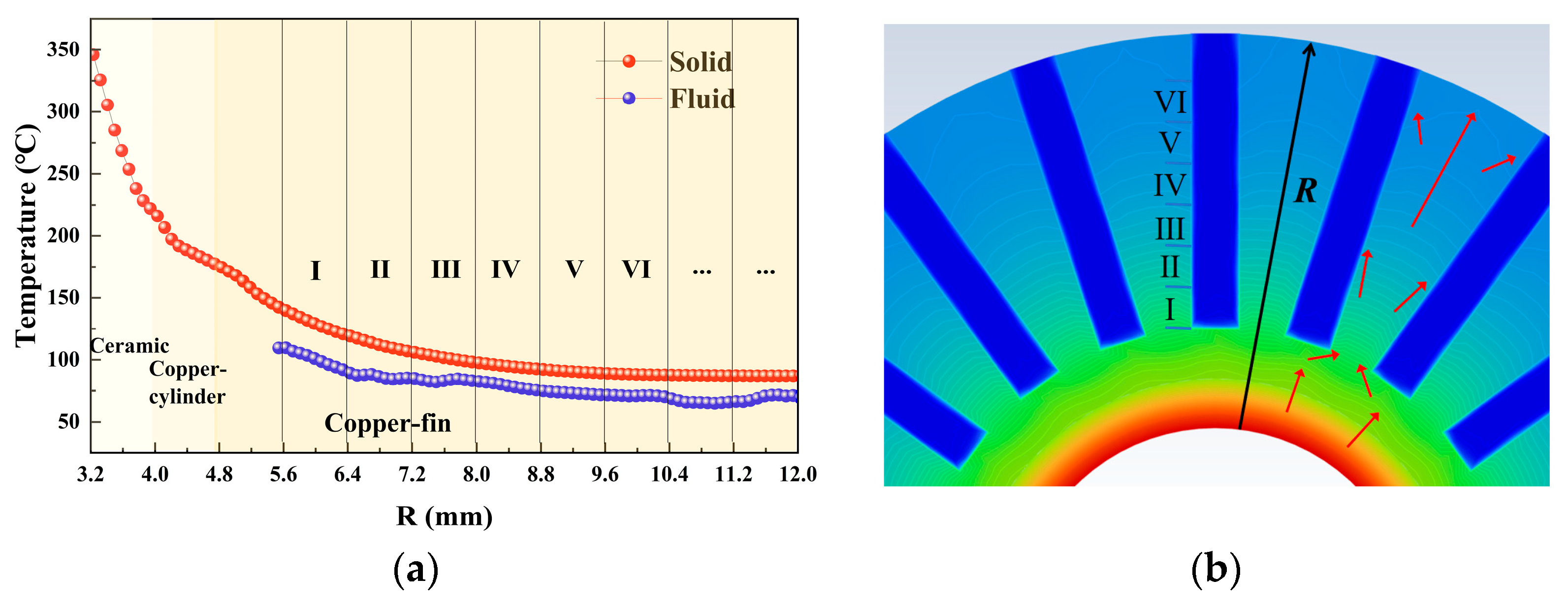

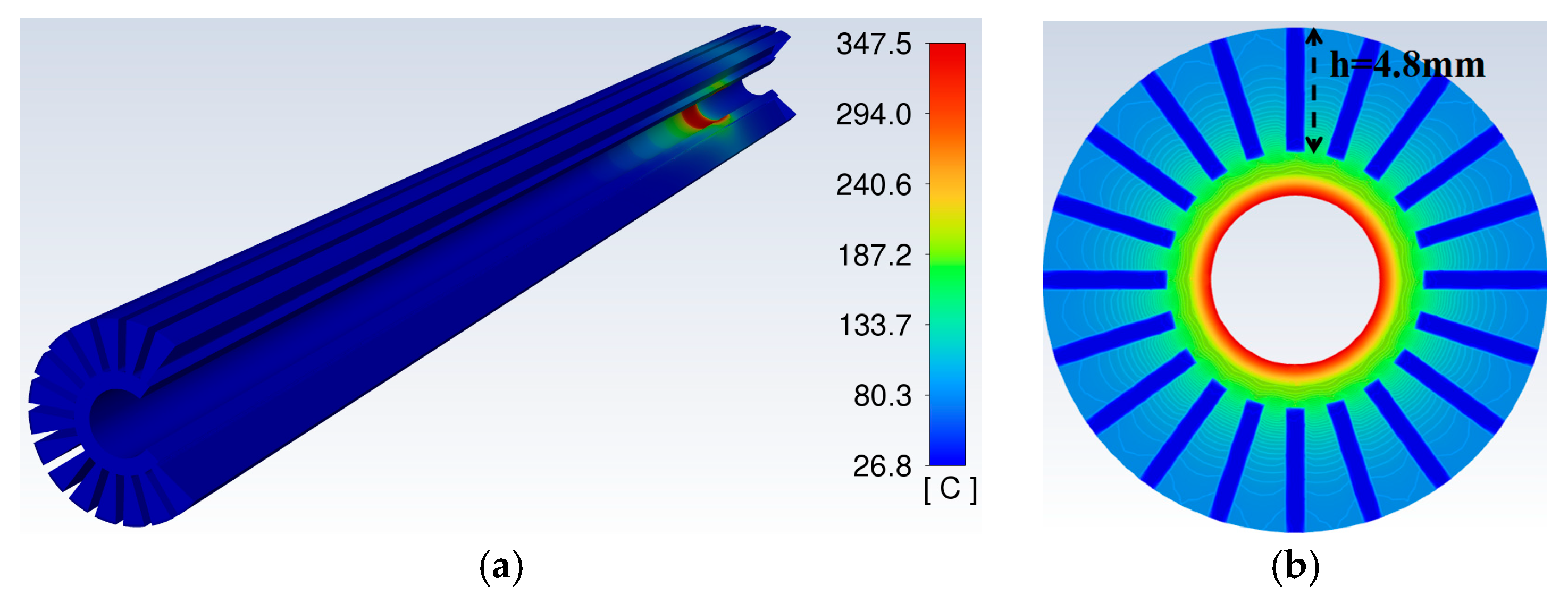

3.2. Cooling Structure with Low Thermal Resistance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thumm, M. Gyro-devices and their applications. In Proceedings of the International Vacuum Electronics Conference, Bangalore, India, 21–24 February 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, K.T.; Calame, J.P.; Pershing, D.E.; Danly, B.G.; Garven, M.; Levush, B.; Antonsen, T.M. Design of a Ka-band gyro-TWT for radar applications. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2001, 48, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.R. The electron cyclotron maser. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2004, 76, 489–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Lu, C.; Dai, B.; Guo, L.; Wang, J.; Pu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Luo, Y. Experiment and Power Capacity Investigation for a Ku-Band Continuous-Wave Gyro-TWT. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 7039–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsonov, S.V.; Levitan, B.A.; Murzin, V.N.; Gachev, I.G.; Denisov, G.G.; Bogdashov, A.A.; Mishakin, S.V.; Fiks, A.S.; Soluyanova, E.A.; Tai, E.M.; et al. Ka-Band Gyrotron Traveling-Wave Tubes with the Highest Continuous-Wave and Average Power. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2014, 61, 4264–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Jiang, W.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Pu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Luo, Y. Design and Experiment of a Dielectric-Loaded Gyro-TWT with a Single Depressed Collector. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 3920–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jintao, Y.; Efeng, W.; Chaojun, L.; Qixiang, Z.; Jinjun, F.; Zihan, L.; Xu, Z. Research on a Ka-band large-orbit gyro-TWT with periodic dielectric-loaded structure. Electron. Lett. 2023, 60, e13068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Jiang, W.; Han, B.; Lu, C.; Yao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y. Investigation of a Magnetron Injection Gun with an External Anode for Ka-Band Gyro-TWT. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2025, 72, 1448–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Dai, B.; Lu, C.; Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Pu, Y.; Luo, Y. High Average Power Investigation of Dielectric Dissipation in the W-Band Gyro-TWT. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 3926–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.R.; Chen, H.Y.; Hung, C.L.; Chang, T.H.; Barnett, L.R. Ultrahigh gain gyrotron traveling wave amplifier. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calame, J.P.; Garven, M.; Danly, B.G.; Levush, B.; Nguyen, K.T. Gyrotron-traveling wave-tube circuits based on lossy ceramics. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2002, 49, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.R.; Barnett, L.R.; Chen, H.Y.; Chen, S.H.; Wang, C.; Yeh, Y.S.; Tsai, Y.C.; Yang, T.T.; Dawn, T.Y. Stabilization of Absolute Instabilities in the Gyrotron Traveling Wave Amplifier. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 74, 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello-Ochende, T.; Liebenberg, L.; Meyer, J.P. Constructal cooling channels for micro-channel heat sinks. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2007, 50, 4141–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.L.; Liu, Z.J.; He, Y.L.; Tao, W.Q. Numerical study of laminar heat transfer and pressure drop characteristics in a water-cooled minichannel heat sink. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2009, 29, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.H.; Choi, D.H.; Kim, S.J. Numerical optimization of the thermal performance of a microchannel heat sink. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2002, 13, 2823–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahar, A.M.; Wissink, J.; Mahmoud, M.M.; Karayiannis, T.G.; Ashrul Ishak, M.S. Effect of hydraulic diameter and aspect ratio on single phase flow and heat transfer in a rectangular microchannel. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 115, 793–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Gao, J. Influence of geometric parameters on flow and heat transfer performance of micro-channel heat sinks. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 107, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Design Goal |

|---|---|

| Beam Voltage () | 60 kV |

| Beam Current () | 8 A |

| Magnetic Field () | 1.13 T |

| Operating Mode | |

| Circuit Radius () | 3.23 mm |

| Number of Ceramics | 20 |

| Linear Segment Length () | 200 mm |

| Nonlinear Segment Length () | 14.5 mm |

| Parameters | Initial Value |

|---|---|

| Ceramic Thickness () | 0.8 mm |

| Copper wall Thickness () | 1 mm |

| Ceramic Ring Length | 10 mm |

| Circuit Radius () | 3.23 mm |

| Width of Channel () | 2 mm |

| Sidewall Width () | 2 mm |

| Height of Channel () | 6 mm |

| Heat Sink Radius () | 11.03 mm |

| Magnet Bore () | 19.03 mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ji, S.; Dai, B.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Chen, X.; Han, B.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Q.; Liu, G.; Yao, Y.; et al. A Compact Heat Sink Compatible with a Ka-Band Gyro-TWT with Non-Superconducting Magnets. Quantum Beam Sci. 2026, 10, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs10010004

Ji S, Dai B, Wu Z, Jiang W, Chen X, Han B, Zhou J, Chen Q, Liu G, Yao Y, et al. A Compact Heat Sink Compatible with a Ka-Band Gyro-TWT with Non-Superconducting Magnets. Quantum Beam Science. 2026; 10(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs10010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Shaohang, Boxin Dai, Zewei Wu, Wei Jiang, Xin Chen, Binyang Han, Jianwei Zhou, Qianqian Chen, Guo Liu, Yelei Yao, and et al. 2026. "A Compact Heat Sink Compatible with a Ka-Band Gyro-TWT with Non-Superconducting Magnets" Quantum Beam Science 10, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs10010004

APA StyleJi, S., Dai, B., Wu, Z., Jiang, W., Chen, X., Han, B., Zhou, J., Chen, Q., Liu, G., Yao, Y., Wang, J., & Luo, Y. (2026). A Compact Heat Sink Compatible with a Ka-Band Gyro-TWT with Non-Superconducting Magnets. Quantum Beam Science, 10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs10010004