2.3. Study Methodology

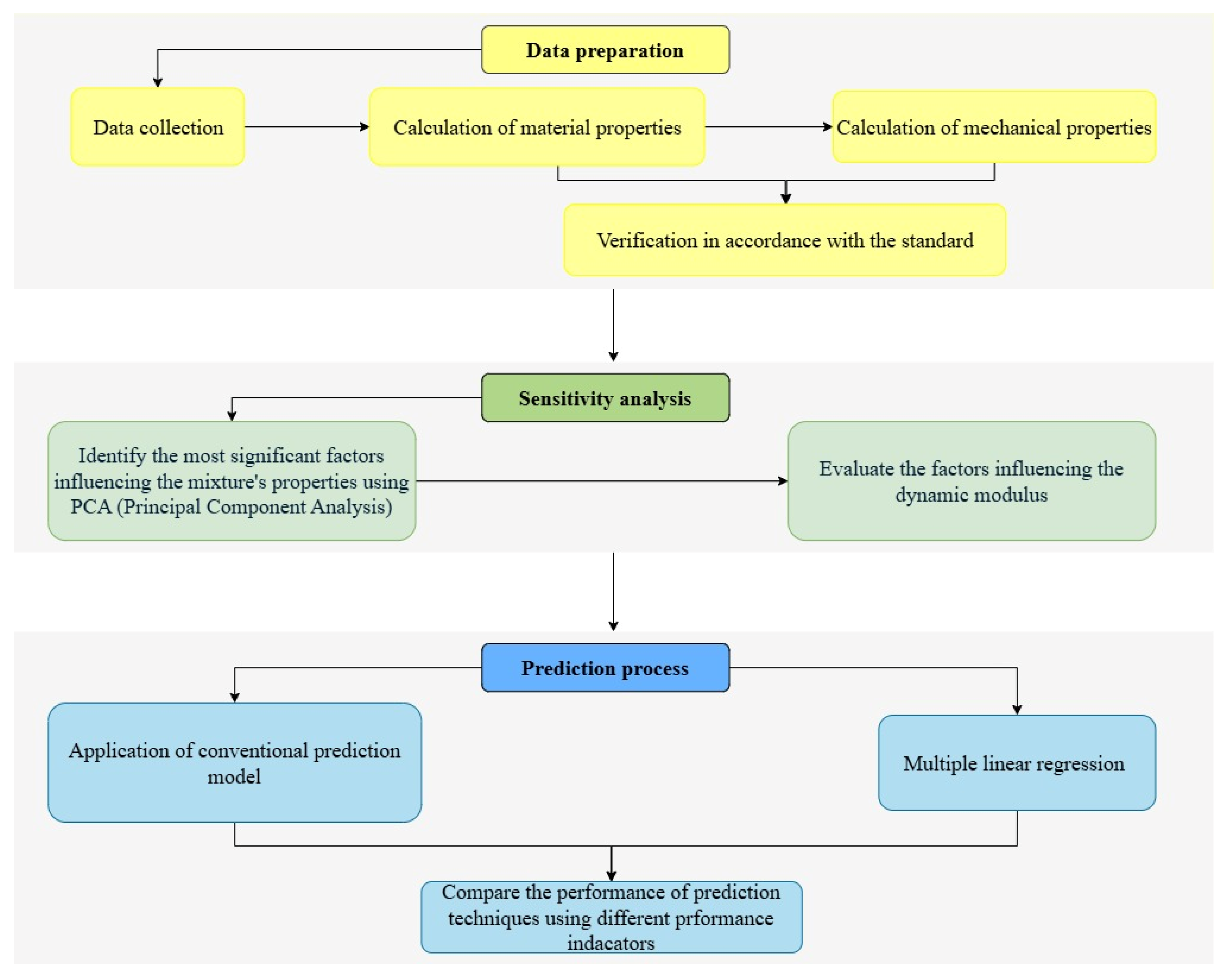

This study proposes a predictive approach for estimating the dynamic modulus of asphalt mixtures incorporating reclaimed asphalt. While the compressive rebound modulus is determined under static loading conditions, the dynamic modulus characterizes material behaviour under repeated cyclic loading and requires more advanced and precise testing instrumentation. In this research, a dataset of dynamic modulus values for selected mixtures was compiled and analysed using grey relational analysis (GRA) to identify the most influential material factors. Based on this analysis, a prediction model was developed through regression fitting and compared to a conventional prediction model. In the case of this study, the sigmoidal model for dynamic modulus prediction is calculated. The methodology flowchart is presented in

Figure 2.

Based on the flowchart of this study, the primary density-related characteristics of the selected asphalt mixtures were investigated. These parameters are basic for evaluating the compaction quality of the mixtures and their internal structures. The maximum density, bulk density, and air void content (Va) were determined for all test specimens, as they serve as preliminary inputs for performance analysis and predictive modelling.

These parameters are interrelated parameters in asphalt mixture designs. Due to their mathematical interdependence, including all of them in the predictive model and in grey relational analysis may introduce redundancy, potentially distorting the interpretability of the statistical analysis. To address this, a principal component analysis (PCA) model was applied in this study to evaluate the degree of correlation among these variables and to extract the principal components that capture the most relevant variance in the data.

In fact, PCA is a statistical tool used for dimensionality reduction, pattern recognition, and exploratory data analysis. Its principal purpose is to reduce and simplify multivariate datasets (many variables) into a set of “principal components” with most of the data’s information. This allows for retaining sets with the most significant information whilst reducing redundancy and noise. It involves a sequence of linear operations. The following steps outline the PCA computation process:

where

X is the original data matrix

, where each column represents a variable (maximum density, bulk density, and air void content)),

μ is the mean of each variable, σ is the standard deviation of each variable, and

Z is the standardized data matrix.

where each eigenvalue

represents the amount of variance explained by its corresponding principal component, and each eigenvector

represents a principal component direction.

This ratio is employed to determine how much information each principal component retains from the original dataset.

Here, is the matrix of the top k eigenvectors, and PC is the new metric with the principal components.

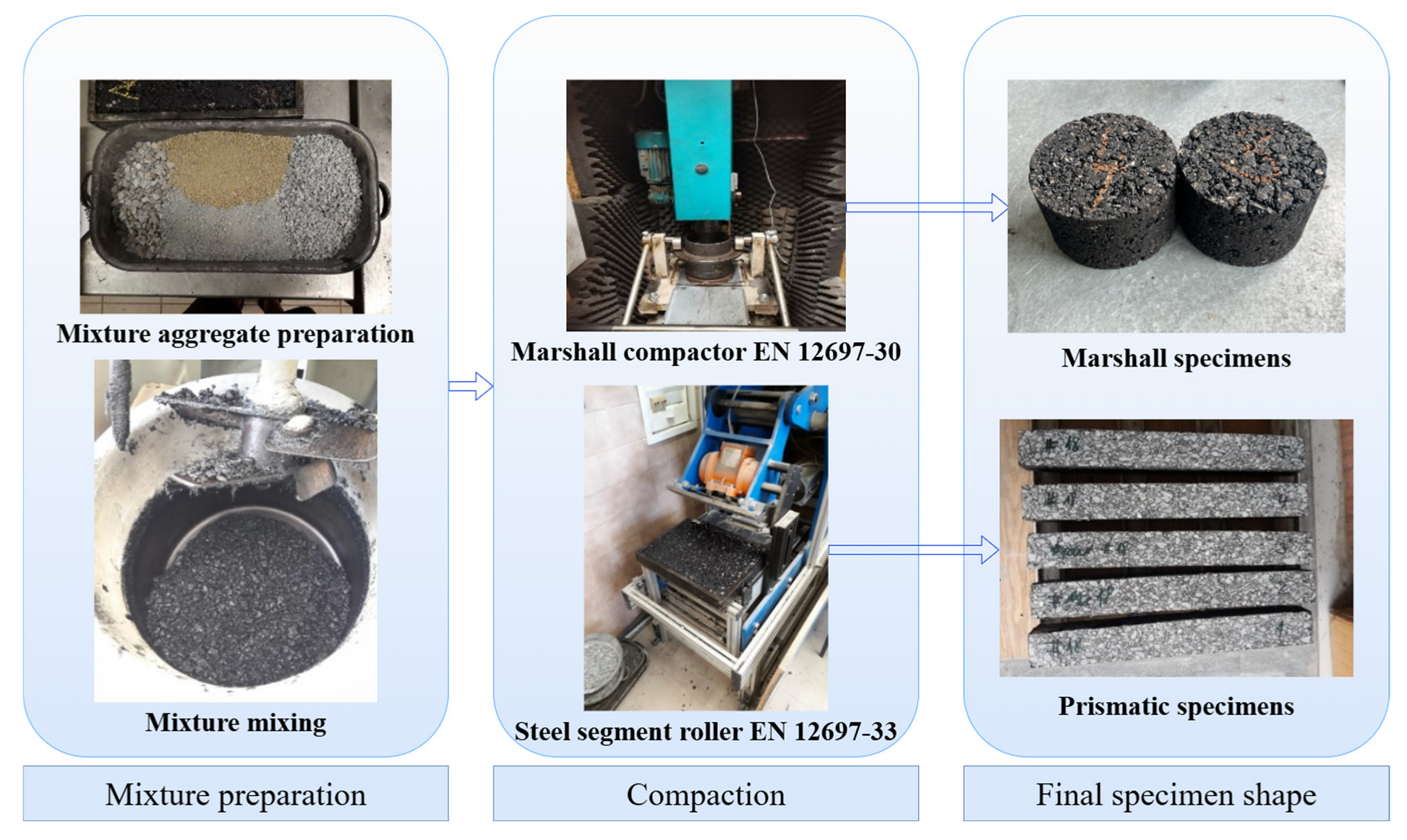

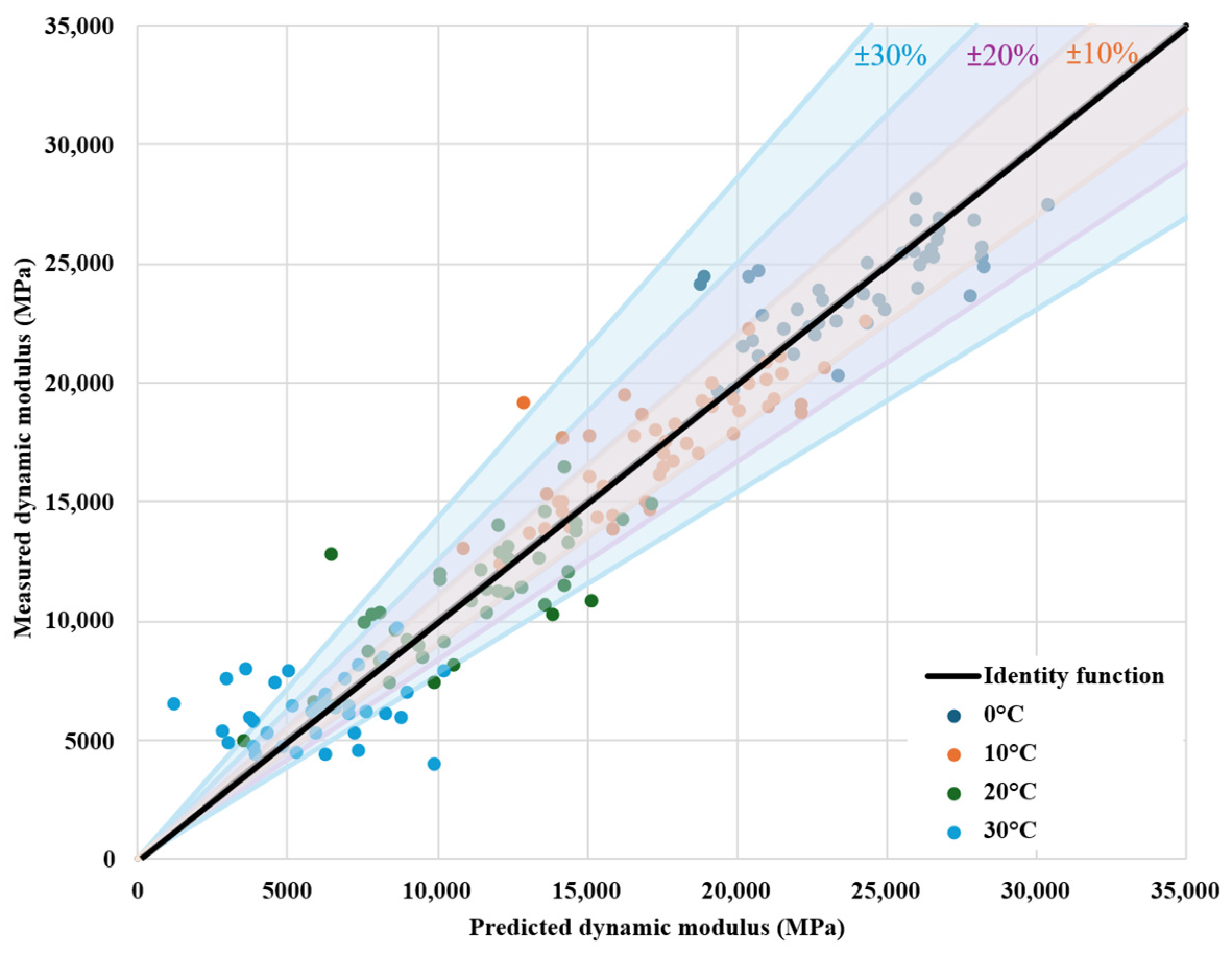

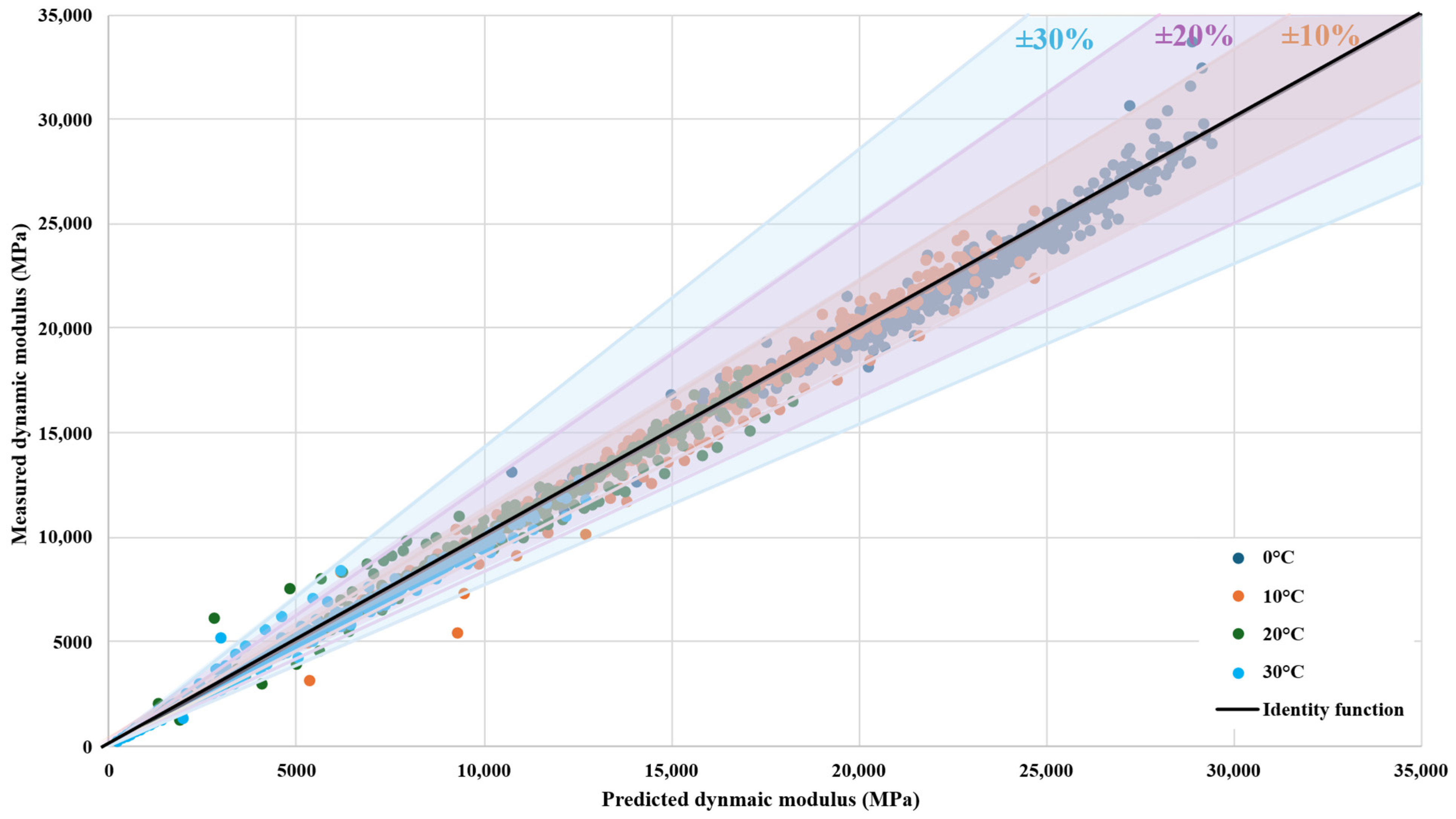

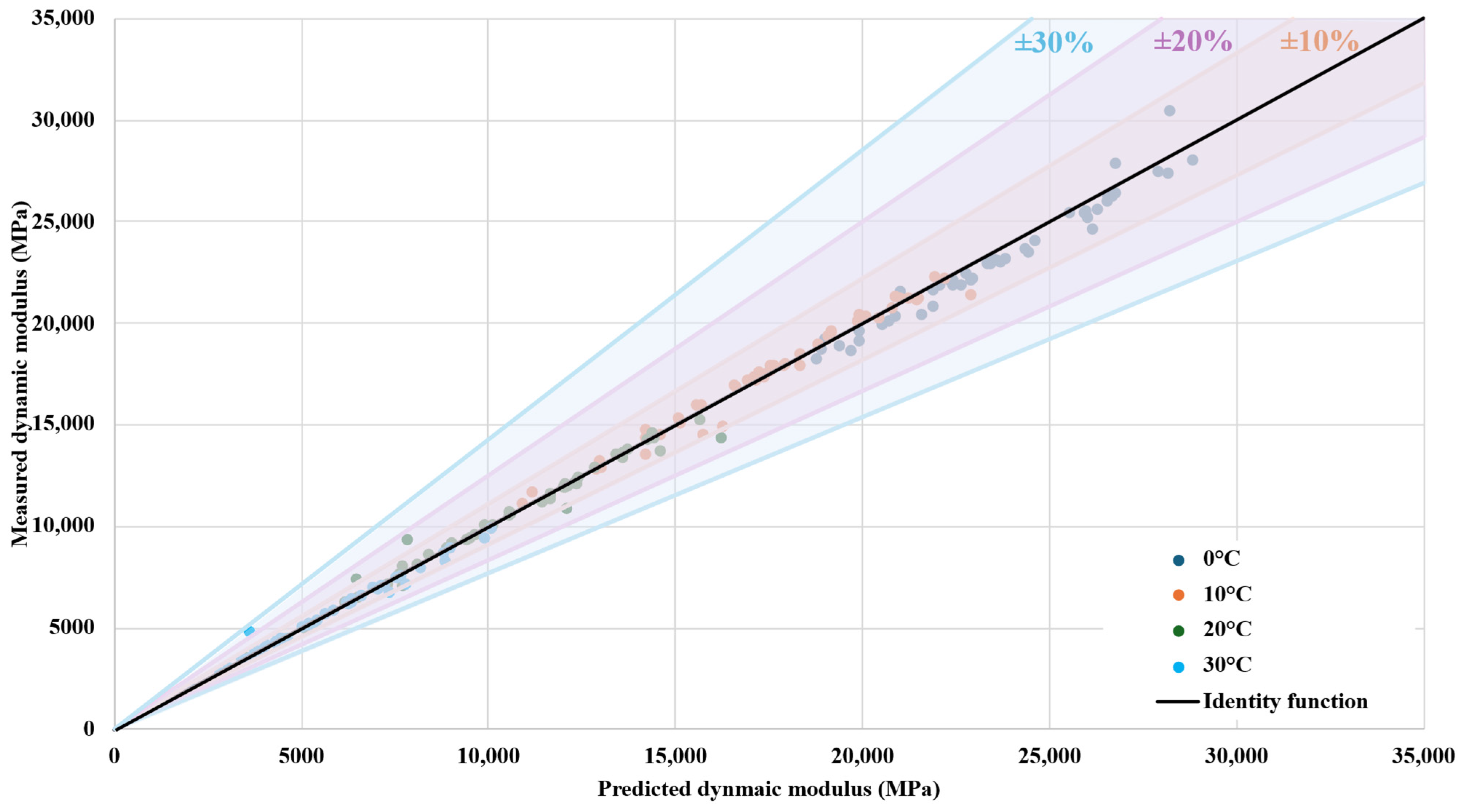

In addition, the mechanical performance of asphalt mixtures was evaluated via two stiffness testing methods: the 4-point bending test on prismatic specimens (4 PB-PR) and the indirect tensile test on cylindrical specimens (IT-CY). The first was employed to measure the dynamic modulus by applying cyclic loads at two loading (upper) points while the beam is supported at two ends (lower points), inducing bending stresses in the middle region of the beam. This test was conducted at four controlled temperatures (0 °C, 10 °C, 20 °C, and 30 °C) and 11 frequencies (50, 30, 20, 15, 10, 8, 5, 3, 2, 1, and 0.1 Hz) in accordance with EN 12697-26 (Annex B), allowing for accurate determination of the dynamic modulus (|E*|) [

31]. In contrast, the second test was conducted to assess the stiffness modulus by applying a compressive load across the vertical diameter of the specimen, inducing a horizontal tensile strain perpendicular to the loading direction. This procedure was conducted under three temperatures (0 °C, 15 °C, and 27 °C) in accordance with EN 12697-26 (Annex C), providing better insight into the tensile performance of asphalt mixtures [

31].

Moreover, the 4PB-PR test provides higher accuracy and a more detailed characterisation of the viscoelastic performance of asphalt mixtures by simulating realistic bending stresses and temperature conditions. However, it requires more resources, advanced equipment, and longer test durations. In contrast, the IT-CY test is relatively less resource-intensive, simpler, faster, and requires less advanced equipment. However, it may provide a less comprehensive assessment of the asphalt mixture since it is less sensitive to characterizing complex material behaviour.

Consequently, an understanding of the relationship between these two tests can enable the more efficient use of static testing for predictive modelling. Therefore, within this study, an analysis of the influencing factors, including the static stiffness modulus, of the dynamic modulus is developed.

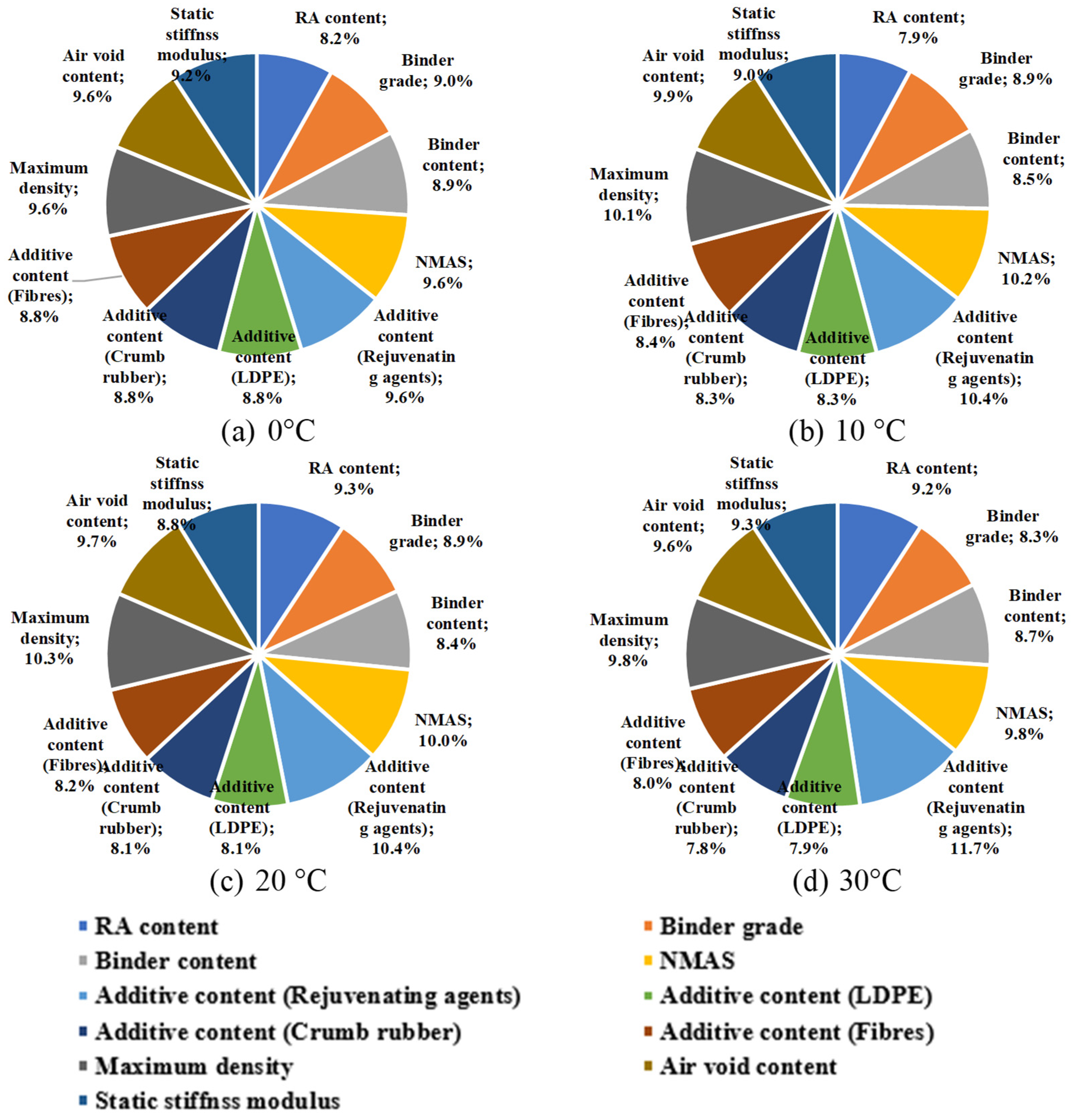

In this perspective, GRA was employed to investigate the influence of material parameters, such as maximum aggregate size (NMAS), binder content, binder grade, bulk density, maximum density, air void content, reclaimed asphalt content, additives, and static stiffness modulus, on the dynamic modulus of asphalt mixtures. GRA is another statistical tool; however, its main purpose is to evaluate and quantify the influence of multiple factors (input variables) on a target property (generally the performance variable of interest) through a normalized similarity comparison. In the context of asphalt mixture engineering, GRA is increasingly applied to assess and rank the influence of mix design parameters on a performance indicator such as the dynamic modulus—a key indicator of the mixture’s performance under traffic loading. The GRA process involves the following steps:

Data normalization helps eliminate dimensional differences among variables. Based on a min–max value method, the normalizations were performed, referring to one of the three scenarios depending on each influencing factor.

For “nominal is better”,

where

is the original value of the

material parameters and the

set of data,

is the normalized value of the correspondent matrix (from 0 to 1),

is the minimum value of the

matrix,

is the maximum value of the

matrix, and

is the target value.

In this study, all raw data were normalized in accordance with the “higher is better” criterion.

The dynamic modulus sequence was defined as the reference sequence while the above designated material parameter sequences were defined as the comparative sequences .

The grey relational coefficient is applied to determine the absolute difference between the normalized value and the reference sequence. It is calculated as

where

is the absolute difference (

),

is the minimum value of the

matrix,

is the maximum value of the

matrix, and

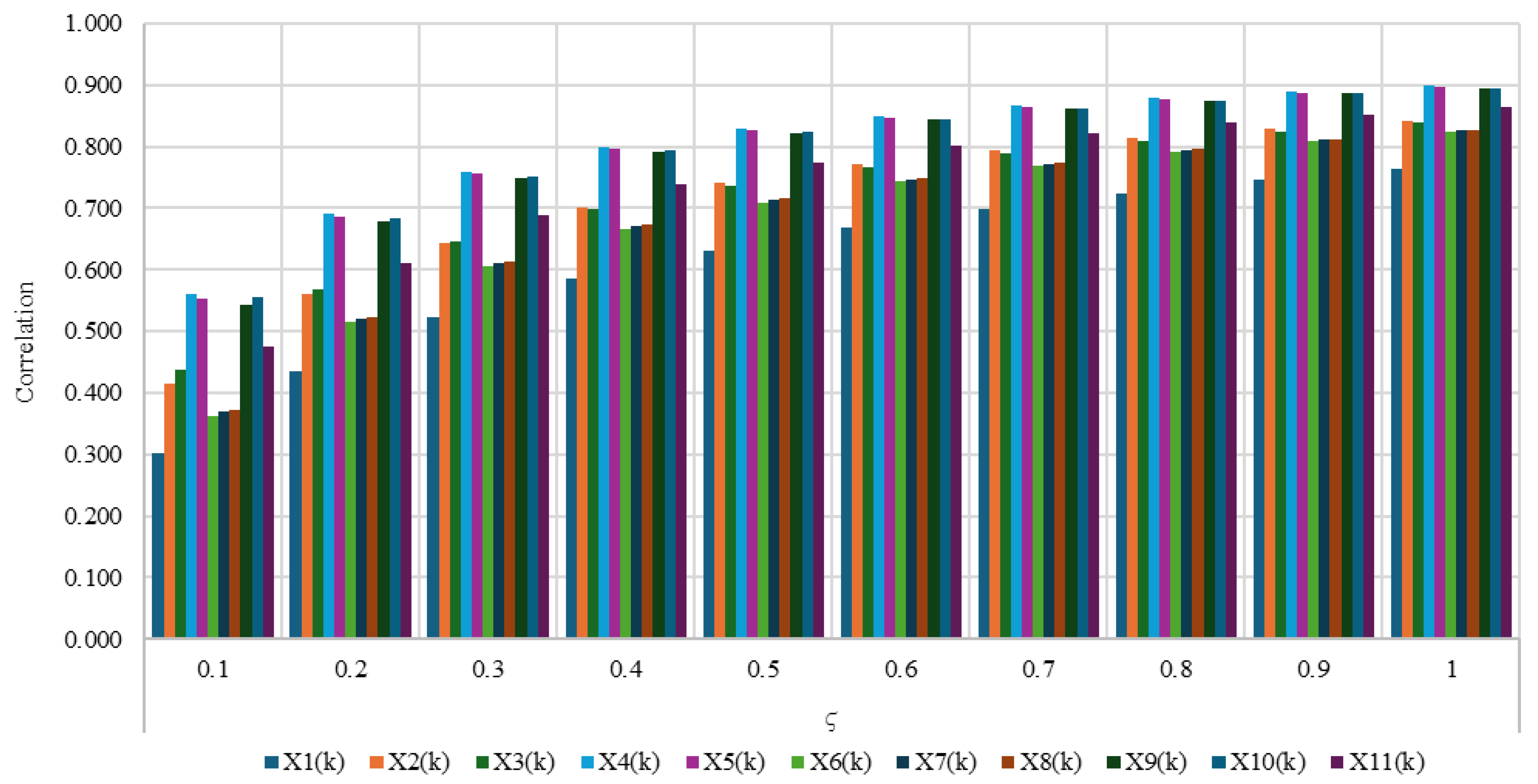

is the resolution coefficient, which reflects the difference in the correlation (

). In this research, through an analysis of all data,

was considered. The results are summarized in

Figure 3.

The sensitivity analysis across different ζ values (0.1–1.0) shows that the relative ranking of influential factors remains largely stable, indicating the robustness of the GRA results. However, at very low ζ values (e.g., 0.1–0.2), the differences between variables become exaggerated, whereas at high ζ values (e.g., >0.7), the distinctions among factors are compressed, reducing discriminatory power. A ζ value of 0.4 offers a balanced compromise, providing sufficient contrast between factors while maintaining stability across the dataset. Therefore, the choice of ζ = 0.4 can be justified as the most representative and reliable setting for capturing the relative influence of key mixture factors.

The grey relational grade represents the overall influence of the i

th factor on the performance matrix. A higher GRG indicates a stronger correlation between the input factor, i.e., the material parameter, and the output variable, i.e., the dynamic modulus. It is calculated as the average of the GRCs for each factor.