Designing and Testing a Tool That Connects the Value Proposition of Deep-Tech Ventures to SDGs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Existing Value Proposition Tools

2.2. Communicating with Investors

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Approach

3.2. Research Setting

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Functional Requirements and Design Solution

- (a).

- The tool helps a deep-tech venture team in developing a value proposition that is based on an in-depth understanding of the (envisioned) customers’ pains, gains and jobs.

- (b).

- The tool helps a deep-tech venture team uncover and dissect how the value proposition can be brought to life for the envisioned customers.

- (c).

- The tool enables a deep-tech venture team to connect the value proposition to at least one (micro) SDG.

- (d).

- The tool requires a deep-tech venture team to develop and present very detailed impact KPIs.

- (e).

- The tool allows a deep-tech venture team to send as many signals about the value proposition as it deems relevant, to minimize the (perceived) information asymmetry between the investors and the venture team.

- (f).

- The tool has an attractive, user-friendly visual interface.

- (g).

- Finally, the tool exploits and integrates existing tools that are already widely used (to fulfil any of the functional requirements above).

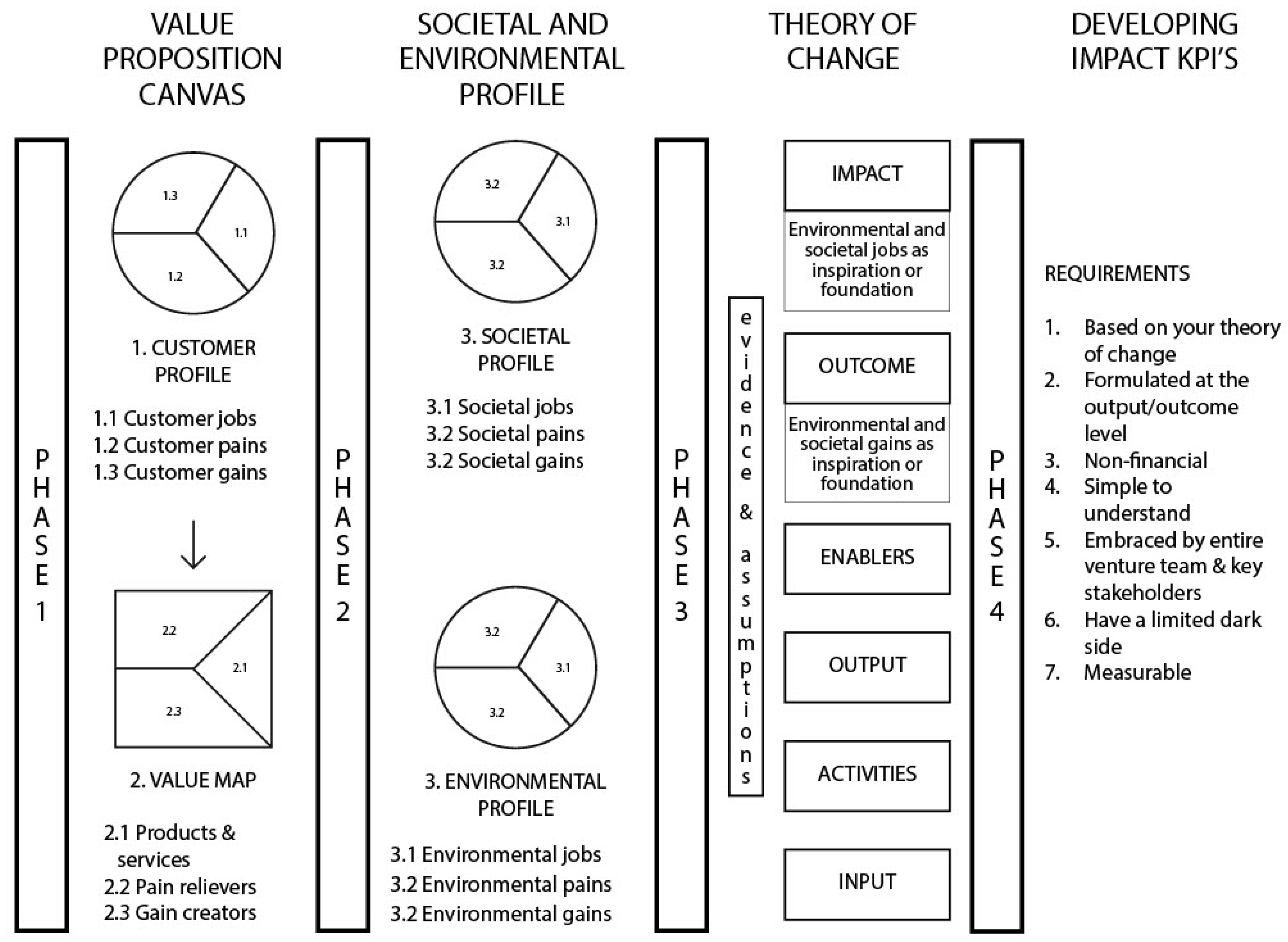

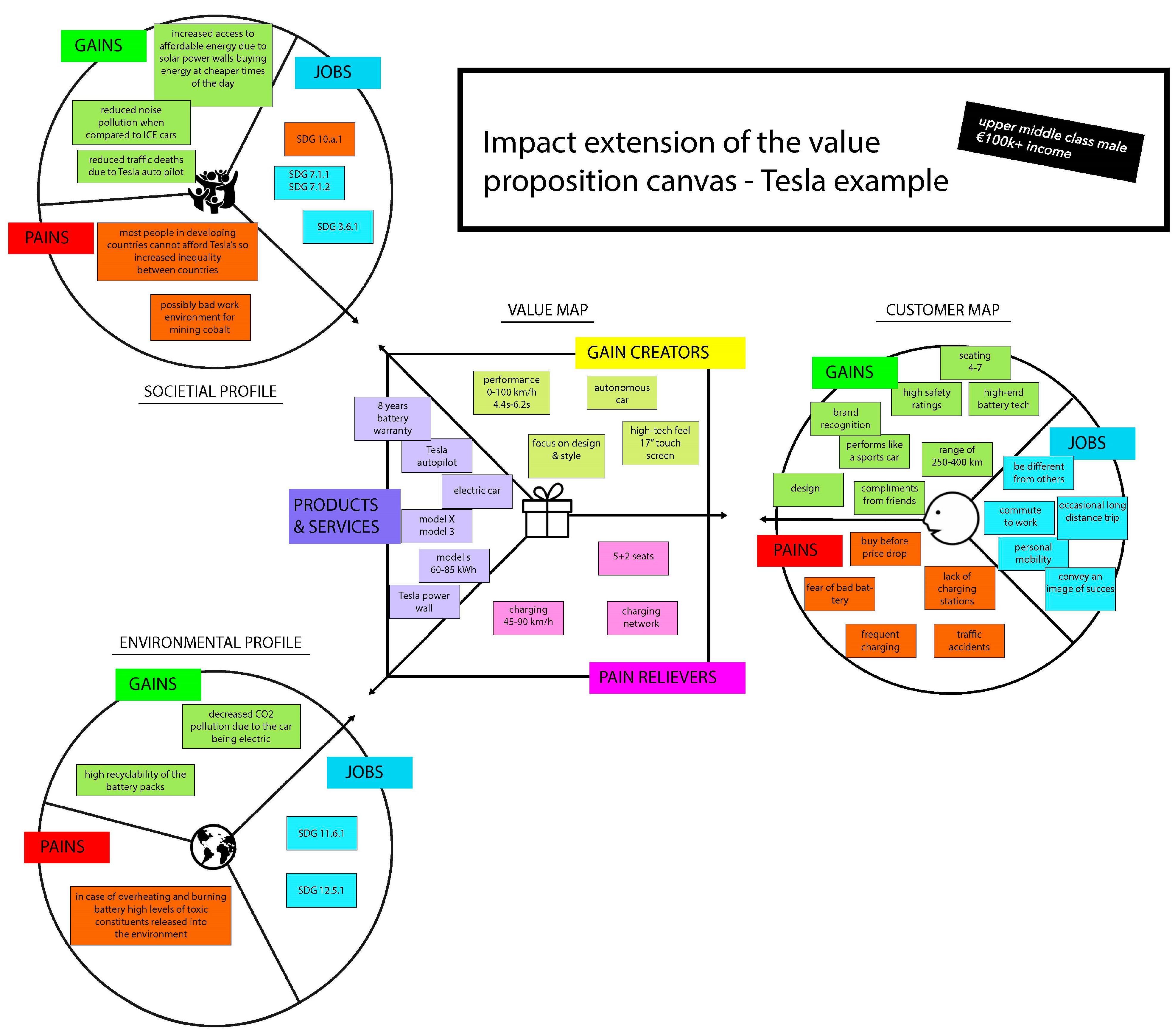

4.1.1. Phase 1: Value Proposition Canvas

4.1.2. Phase 2: Societal and Environmental Profile

- Target 10.a: Implement the principle of special and differential treatment for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, in accordance with World Trade Organization agreements—with indicator 10.a.1: proportion of tariff lines applied to imports from least developed countries and developing countries with zero-tariff.

- Target 7.1: By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services, measured in terms of (indicator 7.1.1) the proportion of the population with access to electricity and (indicator 7.1.2) the proportion of the population with primary reliance on clean fuels and technology).

- Target 3.5: Strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol—indicator 3.5.1: coverage of treatment interventions (pharmacological, psychosocial and rehabilitation and aftercare services) for substance use disorders.

- The targets and indicators in the environmental jobs are:

- Target 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management—indicator 11.6.1: proportion of municipal solid waste collected and managed in controlled facilities out of total municipal waste generated by cities.

- Target 12.5: By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse—indicator 12.5.1: national recycling rate, tons of material recycled.

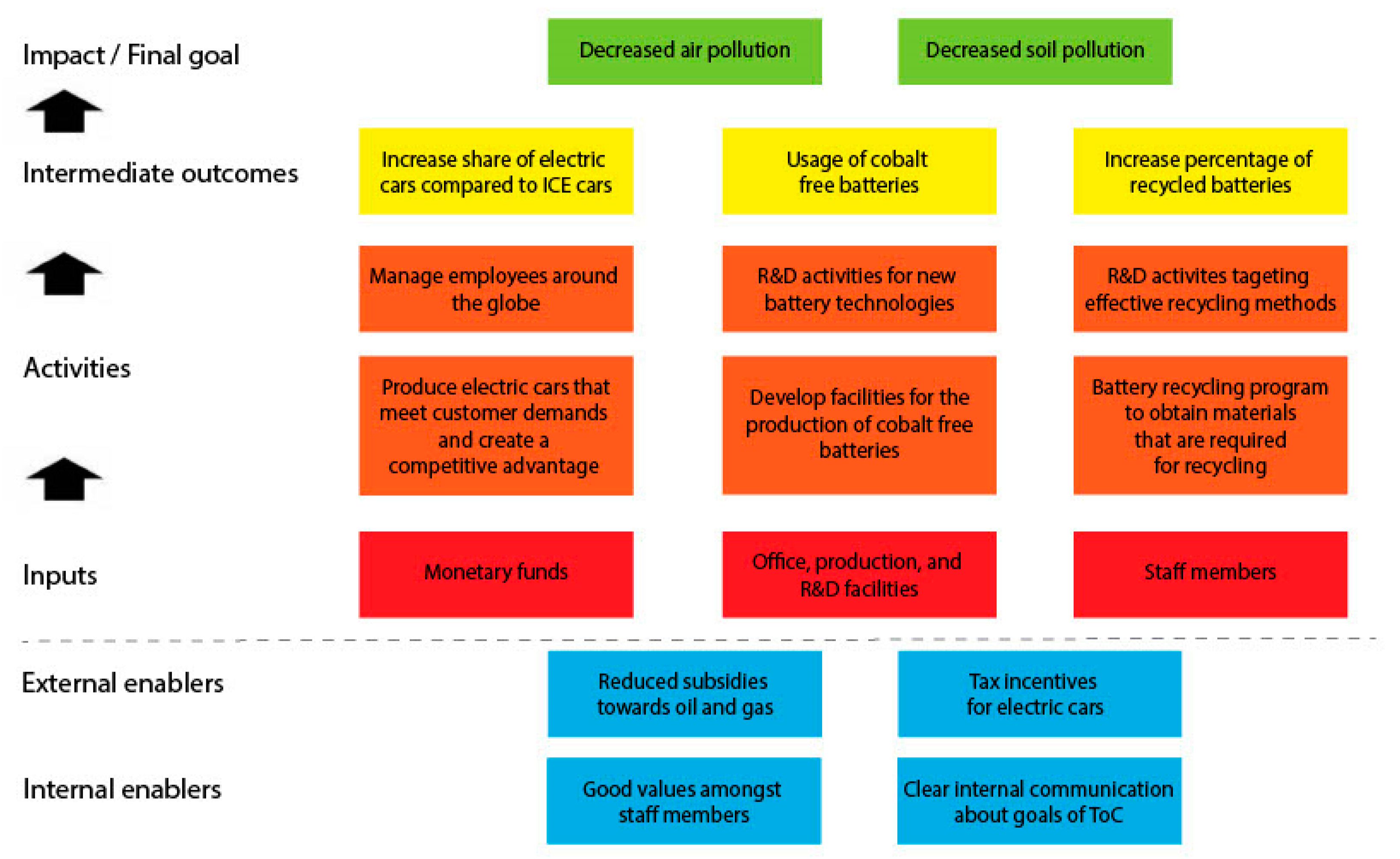

4.1.3. Phase 3: Theory of Change

4.1.4. Phase 4: Impact KPIs

- (1)

- Based on the ToC developed in phase 3—The KPIs describe how a venture intends to measure its impact. The ToC serves to deliver this impact. By linking the venture-specific impact KPIs to the ToC, one ensures that the activities performed contribute to these KPIs and the latter contribute to the final impact.

- (2)

- Formulated at the output/outcome level of the ToC—The output/outcome levels are the last levels that the venture team can directly influence.

- (3)

- Non-financial—The KPIs should be non-financial but nonetheless formulated in volumes or percentages. That is, the KPIs should not be about, for example, return on investment or net profits, but address the (monetary) value of, for instance, reduced carbon dioxide volumes, absence of toxic output in the air, or decreasing numbers of car accidents.

- (4)

- Simple to understand—All relevant stakeholders should immediately understand what is meant by the KPI.

- (5)

- Embraced by the entire venture team and key stakeholders—This broad support ensures all participants (including investors) perform their activities with the same targets in mind.

- (6)

- Have a limited dark side—This targets the potential negative influence measuring one aspect can have on other aspects of the business. The environmental and societal pains formulated in phase 2 of the design solution can serve as inspiration for the dark side of your impact KPI. An example is a venture that seeks to develop an app that provides travelers with historical as well as actual (real-time) information on the on-time arrival of buses, trains and other forms of public transport; this type of app may motivate managers of public transport companies to create incentives and sanctions for (e.g., train) drivers’ performance; the shadow side of the on-arrival KPI is that drivers may reduce the times that doors open at a (couple of) station(s) to ensure on-time arrival at the next station, which in turn may decrease the level of service and customer satisfaction [56].

- (7)

- Measurable—The KPIs should be easy to measure.

- (8)

- In the Tesla case, the KPIs for its first electric vehicle offered at the time could have been, for example:

- in the next five years, we want to sell 3 million Tesla Model S cars;

- we aim to increase the number of batteries without cobalt installed in these cars to 80% in the second year and 95% in the third year;

- in the next eight years, we will increase the percentage of batteries that are fully recycled from (currently) 30% to 90%.

4.2. Alpha and Beta Tests of the Tool

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEO | Chief Executive Officer |

| CFO | Chief Financial Officer |

| DS | Design Science |

| FIR | Final Investment Recommendation |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| SaaS | Software as a Service |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| ToC | Theory of Change |

| UN | United Nations |

| VPC | Value Proposition Canvas |

Appendix A

| Final Impact | The Broader Social Change That Your Venture Is Trying to Achieve |

|---|---|

| Intermediate outcomes | The short-term changes, benefits, learning or other effects that result from the venture’s value proposition. These short-term steps will contribute to a final impact and may include changes in users’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behavior. |

| Outputs | Products, services, or facilities that result from your venture’s activities. These are often expressed quantitatively (e.g., carbon dioxide concentration, kilowatt hours, number of users). |

| Activities | The things that the venture needs to do. Activities remain within the venture team’s control. |

| Inputs | The resources that go into the venture to be able to carry out its activities. |

| Enablers | Conditions that need to be present or absent to allow the venture to succeed. The presence or absence of enablers can help or hinder the venture. There are two kinds of enablers: |

| Internal enablers | internal enablers need to exist inside the venture for a ToC to work, and are mostly within the venture team’s control. These are the mechanisms (e.g., quality management of its production process) by which the venture delivers its outputs. |

| External enablers | External enablers need to exist in the external environment for the ToC to work; they are often beyond the venture team’s immediate control. External enablers often involve socio-cultural, economic and/or political conditions, including prevailing laws, regulations, and (opportunities to develop) close collaborative ties with other companies. |

| Evidence | Information you already have or plan to collect that is relevant to supporting or testing the ToC. |

| Assumptions | The underlying beliefs about how the venture’s value proposition will evolve, the business partners involved, and the broader context. These assumptions are often (initially) implicit in your ToC; by uncovering and explicitly stating them, you become alert and responsive to major external changes that affect the progress and success of your venture. |

Appendix B

| Test | Version | Goal | Outcome | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | Initial solution design | Concept testing with the program manager, to decide whether to extend the VPC by incorporating environmental and societal impact. | This initial solution is in the right direction and has potential, but needs to be further elaborated upon. | The initial idea for the solution will be further refined in the same direction. The SDGs will be included. |

| α2 | First prototype | Validate the added value of the prototype with the Sustainability Officer. | It could definitely be of added value. Good integration of SDGs. To provide applicability to investors it should be combined with a Theory of Change (ToC). | Think about a way to incorporate the ToC in the tool. |

| α3 | First prototype | Get a better perspective on what is important for an investor in a meeting with the managing partner of a deep-tech investment fund. | The tool should be able to develop venture-specific impact KPIs. In beta tests, later-stage startups should also be incorporated as they have a more tangible focus on sustainability. | Tool is very useful. The interviewee also provided access to three Final Investment Recommendation (FIR) documents, to obtain an in-depth insight in the sustainability aspects that investors focus on. |

| α4 | Second prototype | Review the improved extension (i.e., V-model) of the VPC and discuss the potential of using ToC with the program manager. | The V-model has potential. The extension of the VPC is getting shape with the current listing of pains, gains, and jobs. Think about developing a standard profile for each SDG. | Further elaborate upon the V-model. Develop standard profiles for each SDG, where the job will be the generic SDG and its targets and indicators will become the pains and gains. |

| α5 | Third prototype | Gain insight into how impact KPIs are developed and can be linked to ToC with the Sustainability Officer. | The impact KPIs are based on the ToC and should be developed at the output/outcome level. | Integrate the findings with regard to KPIs into the tool. |

| α6 | Fourth prototype | Discuss the new method of integrating the ToC into the tool and possible integration of the tool with the VPC with the program manager. | Tool is shaping up really well; curious about what the final result will be. Keep the tool simple: do not integrate it with the VPC. | Do not try to integrate the other phases of the tool into the VPC; keep the latter as a separate first phase. |

| α7 | Fourth prototype | Validate the readiness for beta-testing with the Sustainability Officer, with a focus on the SDG phase. | Good that the tool highlights both positive and negative environmental and societal impacts: it is important not to motivate the user to only spell out positive influences, when these are hard to find. The tool can also be used as part of a CRM system. There could be different types of impact KPIs: venture-specific ones and generic KPIs for all ventures. | No further changes need to be made to the tool. |

| α8 | Fourth prototype | Validate the current prototype with a venture support manager. | The foundation of the tool is good. Currently the slides still need a bit of explanation to fill out the tool. The dark side in the impact KPIs can be linked to environmental and societal pains. Future work should explore whether the negative/positive SDGs impacts can be effectively weighed against each other. | More elaborately explain the tool and its usage in various slides. In addition, develop new slides to show a completed example (using public data on Tesla). No other changes needed. |

| α9 | Fifth prototype | Decide with the CEO whether the tool is ready to start beta testing with ventures. | Tool is ready for beta testing. | Start with the beta-tests. |

| Test | Version | Goal | Outcome | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β1 | Fifth prototype | CEO of an early-stage deep-tech venture uses the tool. | The extension of the VPC is strong. The framework leads to new insights, especially on the pains side. Requirements for impact KPIs were clear. | No further changes needed based on this test. |

| β2 | Fifth prototype | Chief Product Officer and Chief Sales Officer of an early-stage venture together apply the tool. | This is a very useful tool. Better than the widely used VPC, which provides limited opportunities to look at negative aspects; risk analysis does exist in VPC, but focuses solely on system itself. This tool includes external stakeholders and has strong linkage with the SDGs. The tool could also be used for quick analysis of the effects of different supply chain choices. Can be difficult to make all KPIs non-financial. When selecting SDGs, try to go to the level of micro-targets and/or indicators. | Change order of the slides to match the template. Reconsider the necessity of making (all) impact KPIs non-financial. |

| β3 | Sixth prototype | The CFO and Sustainability/Operations manager of an early-stage deep-tech venture apply the tool. | Tool is very easy to use; proper results can be achieved within an hour. Good that the tool also focuses on the negative impact; many ventures do not take that into consideration, which implies only the good parts are highlighted to potential investors. This test also provided new insights for this specific venture team. | The tool does not need any further changes. A few spelling errors in the slides have to be adjusted. |

References

- Harlé, N.; Soussan, P.; De La Tour, A. What Deep-Tech Startups Want from Corporate Partners; Report by Boston Consulting Group & Hello Tomorrow; Boston Consulting Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://web-assets.bcg.com/img-src/BCG-What-Deep-Tech-Startups-Want-from-Corporate-Partners-Apr-2017_tcm9-150440.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Portincaso, M.; Gourévitch, A.; de la Tour, A.; Legris, A.; Salzgeber, T.; Hammoud, T. The Deep Tech Investment Paradox: A Call to Redesign the Investor Model; Report by Boston Consulting Group & Hello Tomorrow; The Boston Consulting Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://hello-tomorrow.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Deep-Tech-Investment-Paradox-BCG.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Romme, A.G.L. Against all odds: How Eindhoven emerged as a deeptech ecosystem. Systems 2022, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EARTO. The European Innovation Council: A New Framework for EU Innovation Policy; Report by European Association of Research and Technology Organisations (EARTO); EARTO: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://www.earto.eu/wp-content/uploads/EARTO_Paper_-_European_Innovation_Council.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Payne, A.; Frow, P.; Eggert, A. The customer value proposition: Evolution, development, and application in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomenthal, A. Asymmetric information in economics explained. Investopedia. 19 January 2021. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/asymmetricinformation.asp (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Renoldi, M. A Record Year for Impact Innovation. Dealroom. 4 November 2021. Available online: https://dealroom.co/blog/2021-a-record-year-for-impact-innovation (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Pascal, A.; Thomas, C.; Romme, A.G.L. Developing a human-centred and science-based approach to design: The Knowledge Management Platform project. Br. J. Manag. 2013, 24, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romme, A.G.L.; Endenburg, G. Construction principles and design rules in the case of circular design. Organ. Sci. 2006, 17, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Bernarda, G.; Smith, A. Value Proposition Design: How to Create Products and Services Customers Want, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Den Ouden, E. Innovation Design: Creating Value for People, Organizations and Society; Springer: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review. January–February 2011, pp. 62–77. Available online: https://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Straker, K.; Nusem, E. Designing value propositions: An exploration and extension of Sinek’s ‘Golden circle’ model. J. Des. Bus. Soc. 2019, 5, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straker, K.; Wrigley, C. From a mission statement to a sense of mission: Emotion coding to strengthen digital engagements. J. Creat. Value 2018, 4, 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, D. The Pitch Canvas. Available online: https://best3minutes.com/the-pitch-canvas/ (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Camburn, B.A.; Arlitt, R.; Perez, K.B.; Anderson, D.; Choo, P.K.; Lim, T.; Gilmour, A.; Wood, K. Design prototyping of systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Design, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 August 2017; Volume 3, pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.L.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Product development: Past research, present findings, and future directions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 343–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priego, L.P.; Wareham, J.; Romasanta, A.; Rothe, H. Deep Tech: Emerging Opportunities in Innovation and Entrepreneurship. In Proceedings of the ICIS, Austin, TX, USA, 12–15 December 2001; Volume 3. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2021/pdw/pdw/3 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Steiber, A.; Alänge, S. Corporate-startup co-creation for increased innovation and societal change. Triple Helix 2020, 7, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyhnau, J.; Nielsen, C. Book review of “Value proposition design: How to create products and services customers want”. J. Bus. Model. 2015, 3, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.; Short, S.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling. Corp. Gov. 2013, 13, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucknell Bossen, C.; Kottasz, R. Uses and gratifications sought by pre-adolescent and adolescent TikTok consumers. Young Consum. 2020, 21, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molling, G.; Klein, A. A framework for IoT-based products and services value proposition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Resources Management, 28–29 May 2020; Volume 13. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/confirm2020/29/ (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Vladimirova, D. Building sustainable value propositions for multiple stakeholders: A practical tool. J. Bus. Model. 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P.; Barnes, M. Constructing theories of change. Evaluation-US 2007, 13, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.T. Interrogating the theory of change: Evaluating impact investing where it matters most. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2013, 3, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. Sustainable value analysis tool for value creation. Asian J. Manag. Sci. Appl. 2014, 1, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, N.; Griffiths, A. The natural environment as a primary stakeholder: The case of climate change. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, T.; Kuckertz, A. Investor relations for start-ups: An analysis of venture capital investors’ communicative needs. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2006, 34, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Bönte, W.; Mahagaonkar, P. Financial signaling by innovative nascent ventures: The relevance of patents and prototypes. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1407–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, B.F.; Letterie, W.A. Business starters and credit rationing. Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 30, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Stark, M. What do investors look for in a business plan? Int. Small Bus. J. 2004, 22, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Blease, J.R.; Sohl, J.E. New venture legitimacy: The conditions for angel investors. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 45, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Knight, A. Resources and relationships in entrepreneurship: An exchange theory of the development and effects of the entrepreneur-investor relationship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, D.M. Financing the next Silicon Valley. Wash. Univ. Law Rev. 2009, 87, 717–762. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, R.; Petersen, B. Capital market imperfections, high-tech investment, and new equity financing. Econ. J. 2002, 112, F54–F72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bam, J.A.C.; Silverman, B.S. Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology startups. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.; Fisch, C.; Vismara, S.; Andres, R. Private equity investment criteria: An experimental conjoint analysis of venture capital, business angels, and family offices. J. Corp. Financ. 2019, 58, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.; Kotha, S.; Lahiri, A. Changing with the times: An integrated view of identity, legitimacy, and new venture life cycles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.H.; Ziedonis, R.H. Resources as dual sources of advantage: Implications for valuing entrepreneurial-firm patents. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 761–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurosif. Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation. Available online: https://www.eurosif.org/policies/sfdr/ (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- SDG Compass: The Guide for Business Action on the SDGs; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Available online: https://sdgcompass.org/ (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Shift Invest. Turning Investments into Impact. Available online: https://shiftinvest.com/impact (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Oberlack, C.; Breu, T.; Giger, M.; Harari, N.; Herweg, K.; Mathez-Stiefel, S.-L.; Messerli, P.; Moser, S.; Ott, C.; Providoli, I.; et al. Theories of change in sustainability science: Understanding how change happens. GAIA 2019, 28, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.H. How can theory-based evaluation make greater headway? Eval. Rev. 1997, 21, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paina, L.; Wilkinson, A.; Tetui, M.; Ekirapa-Kiracho, E.; Barman, D.; Ahmed, T.; Mahmood, S.S.; Bloom, G.; Knezovich, J.; George, A.; et al. Using Theories of Change to inform implementation of health systems research and innovation: Experiences of Future Health Systems consortium partners in Bangladesh, India and Uganda. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2017, 15, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, E.; Hodgson, L.; Noble, J. Creating Your Theory of Change: NPC’s Practical Guide; NPC: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.thinknpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Creating-your-theory-of-change1.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Holmström, J.; Ketokivi, M.; Hameri, A.P. Bridging practice and theory: A design science approach. Decis. Sci. 2009, 40, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romme, A.G.L. Making a difference: Organization as design. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 558–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romme, A.G.L.; Dimov, D. Mixing oil with water: Framing and theorizing in management research informed by design science. Designs 2021, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romme, A.G.L.; Holmström, J. From theories to tools: Calling for research on technological innovation informed by design science. Technovation 2023, 121, 102692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bamana, G.; Miller, J.D.; Young, S.L.; Dunn, J.B. Addressing the social life cycle inventory analysis data gap: Insights from a case study of cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. One Earth 2021, 4, 1704–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesla. Q1 2022 Update. Available online: https://cdn.motor1.com/pdf-files/tsla-q1-2022-update.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Parmenter, D. Key Performance Indicators: Developing, Implementng, and Using Winning KPIs, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Freitas Netto, S.V.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; Da Luz Soares, G.R. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutselaars, J. Communicating the Value Proposition of New Deep-Tech Ventures to Investors. Master’s Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2022. Available online: https://pure.tue.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/271733451/Master_Thesis_Joppe_Schutselaars.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schutselaars, J.; Romme, A.G.L.; Bell, J.; Bobelyn, A.S.A.; van Scheijndel, R. Designing and Testing a Tool That Connects the Value Proposition of Deep-Tech Ventures to SDGs. Designs 2023, 7, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs7020050

Schutselaars J, Romme AGL, Bell J, Bobelyn ASA, van Scheijndel R. Designing and Testing a Tool That Connects the Value Proposition of Deep-Tech Ventures to SDGs. Designs. 2023; 7(2):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs7020050

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchutselaars, Joppe, A. Georges L. Romme, John Bell, Annelies S. A. Bobelyn, and Robin van Scheijndel. 2023. "Designing and Testing a Tool That Connects the Value Proposition of Deep-Tech Ventures to SDGs" Designs 7, no. 2: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs7020050

APA StyleSchutselaars, J., Romme, A. G. L., Bell, J., Bobelyn, A. S. A., & van Scheijndel, R. (2023). Designing and Testing a Tool That Connects the Value Proposition of Deep-Tech Ventures to SDGs. Designs, 7(2), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs7020050