Multimodal Rehabilitation Management of a Misunderstood Parsonage–Turner Syndrome: A Case Report during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Report

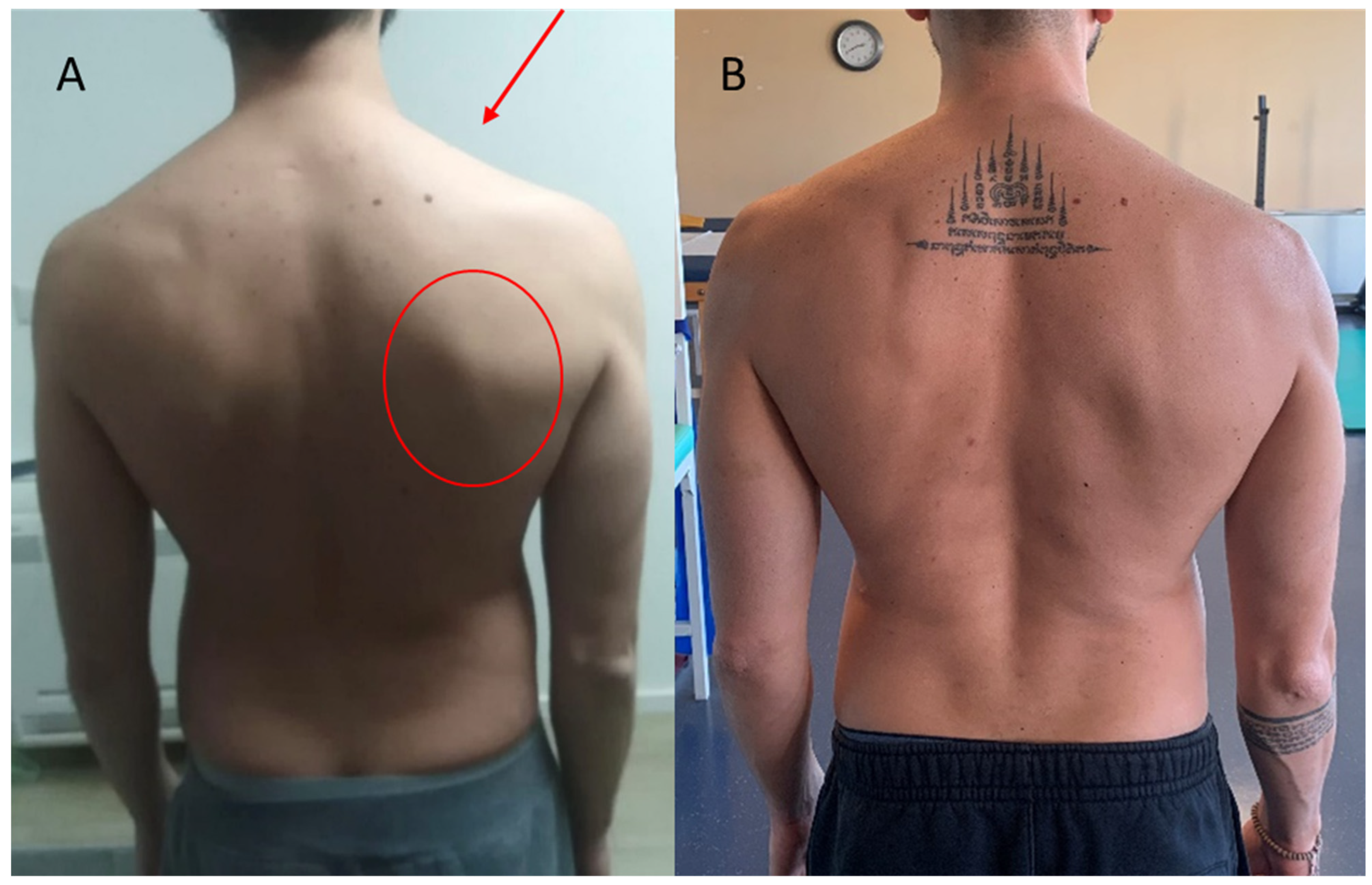

2.2. Clinical Findings

2.3. Diagnostic Assessment

2.4. Therapeutic Intervention

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

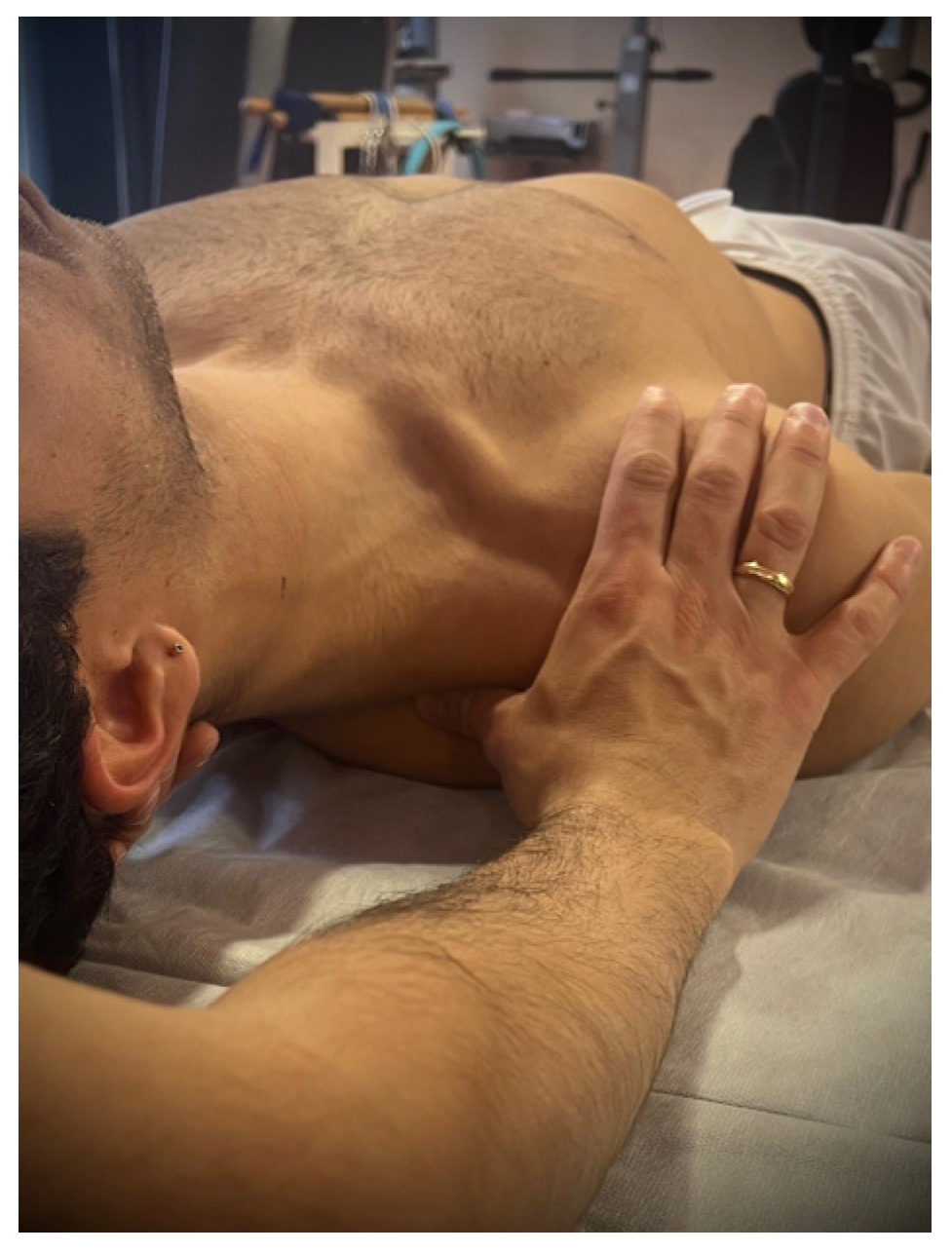

- Myofascial release of the target muscles: a low-load and long-duration stretch to the barriers in the myofascial tissue is applied for modulate pain. The upper trapezius, the sternocleidomastoid, and the rhomboid muscles were mainly treated. The aim of this technique is to modulate pain. We used myofascial release for the first 5 sessions.

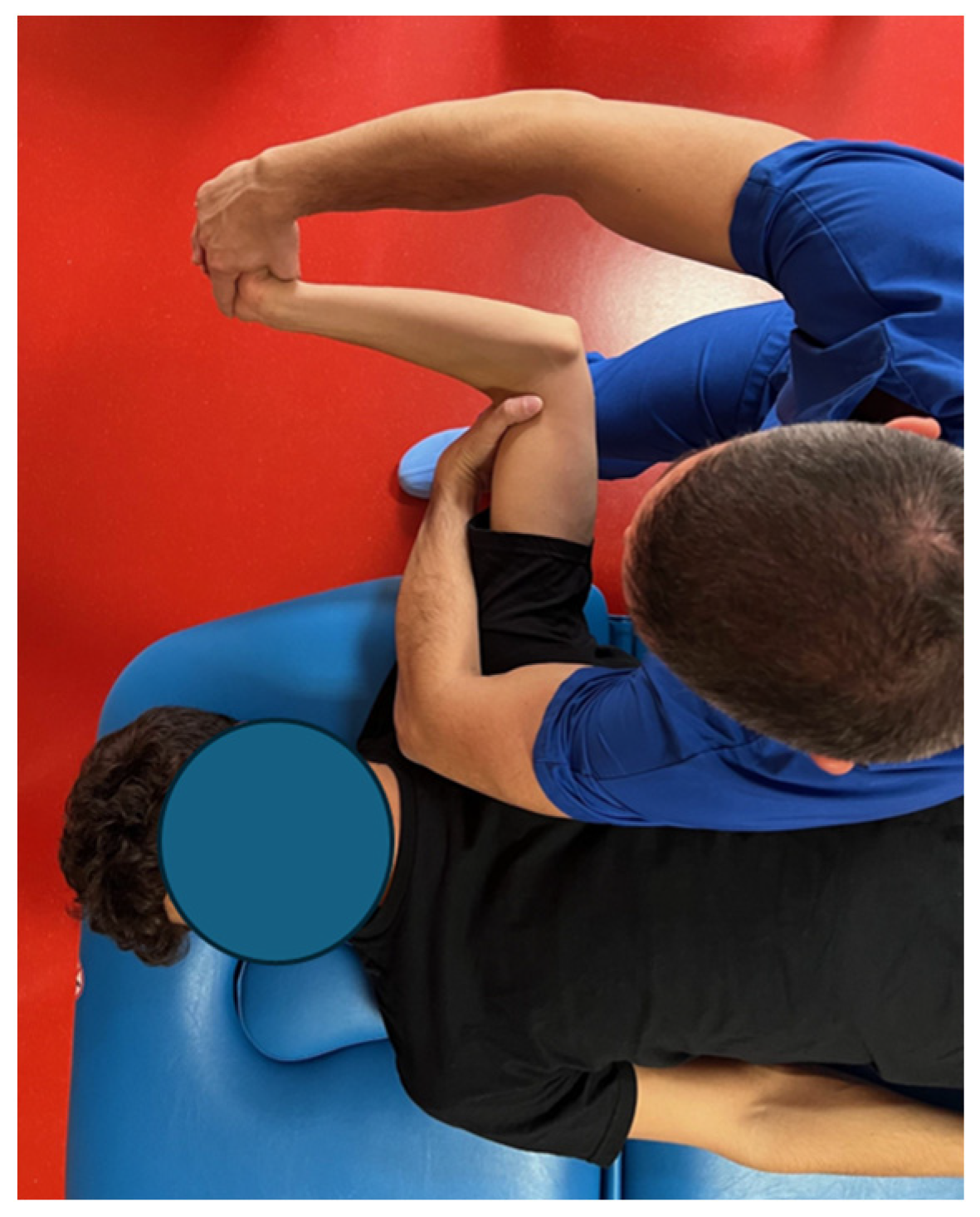

- Neurodynamic techniques for mechanosensitivity: The aim of this technique was to initially reduce neuro tension (slider in–out) reproducing the upper limb neural tension 1 (ULNT1) on the healthy limb, and then move on to increase neuro tension (slider out–in), reproducing the ULTN1 on the affected limb (Figure A2). The aim of this technique is to reduce neuropathic symptoms and improve neuro tension. We used neurodynamic techniques for the first 10 physiotherapy sessions.

- Shoulder elastic taping: We used this technique in the short term, as described in the literature [13].

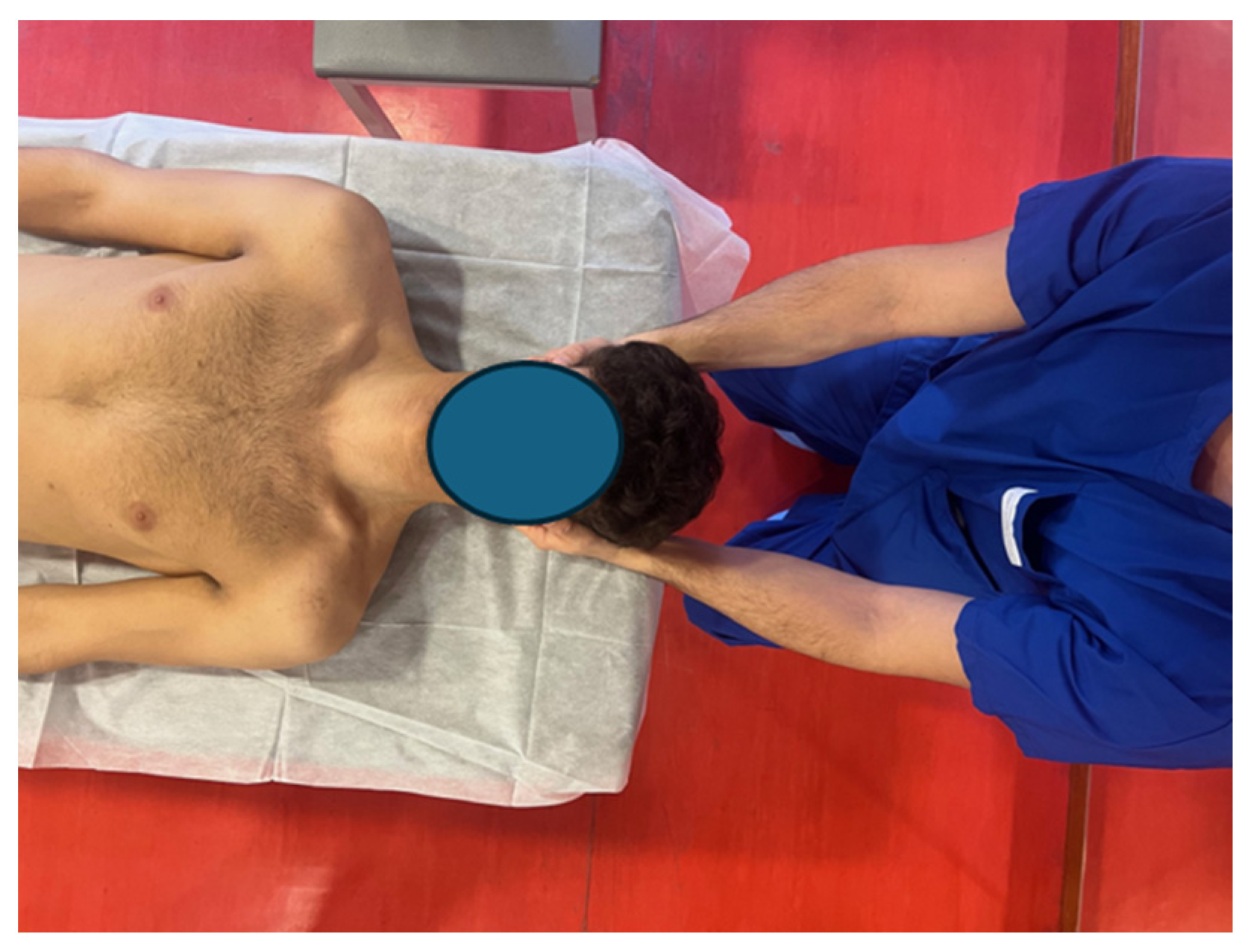

- Pompage techniques of the cervical spine, trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, and levator scapulae: Pompage is a manual technique typically used in physiotherapy. It acts on both muscular components of the joint as well as interapophyseal areas. The technique consists of gradual, assisted tensions, which compress small intervertebral joints and stretch spinal ligaments and muscles (Figure A3 and Figure A4). The aim of this technique is to modulate pain. We used these techniques in the first 20 physiotherapy sessions.

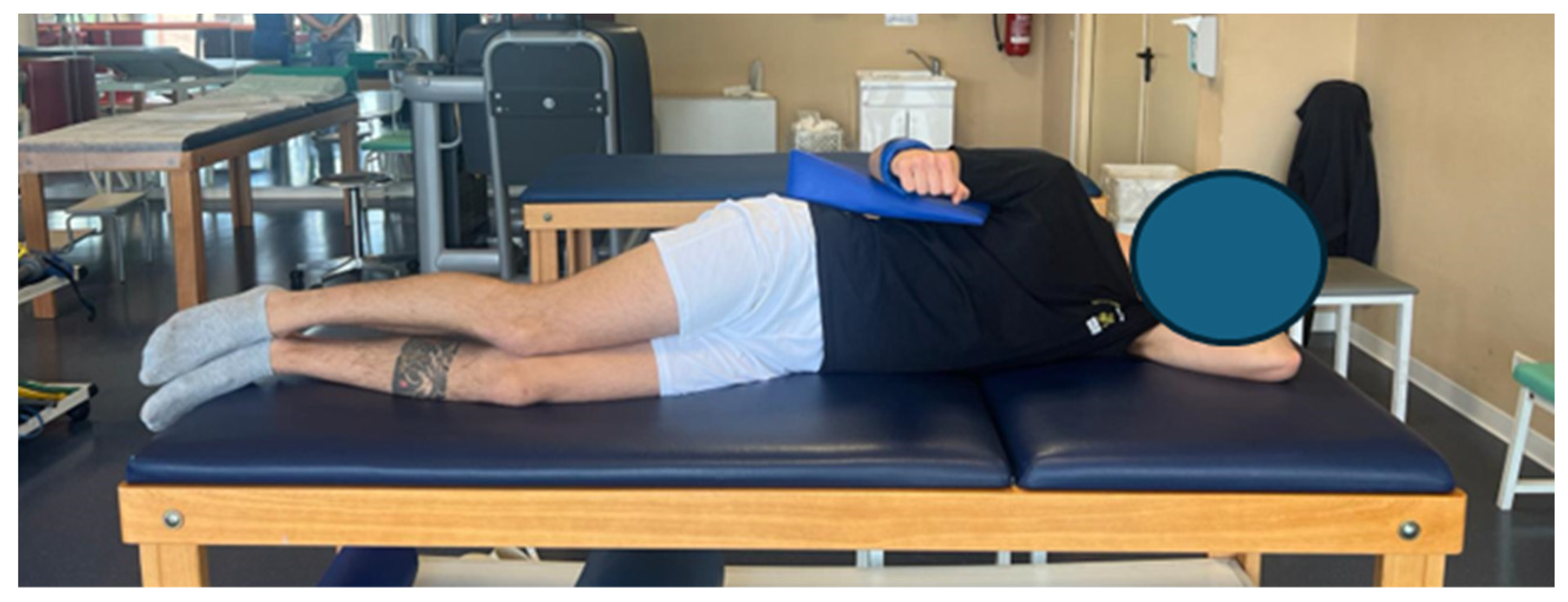

- Mobilization with movement (MWM): According to the Mulligan Concept, the aim of this technique is to improve range of motion thanks to the application of a sustained gliding force with a concurrent active movement performed by the patient. We used these techniques in all 20 initial sessions (Figure A5).

- Manipulations of the dorsal spine: We used a high-velocity low-amplitude technique (HVLAT), known in the literature as “dog”, for the middle thoracic vertebrae for modulating pain. This technique is described as “a skilled, passive manual therapeutic maneuver during which a synovial joint is beyond the normal physiological range of movement (in the direction of the restriction) without exceeding the boundaries of anatomical integrity [23]”. We used this technique two times, at the beginning of the treatment and 14 days later.

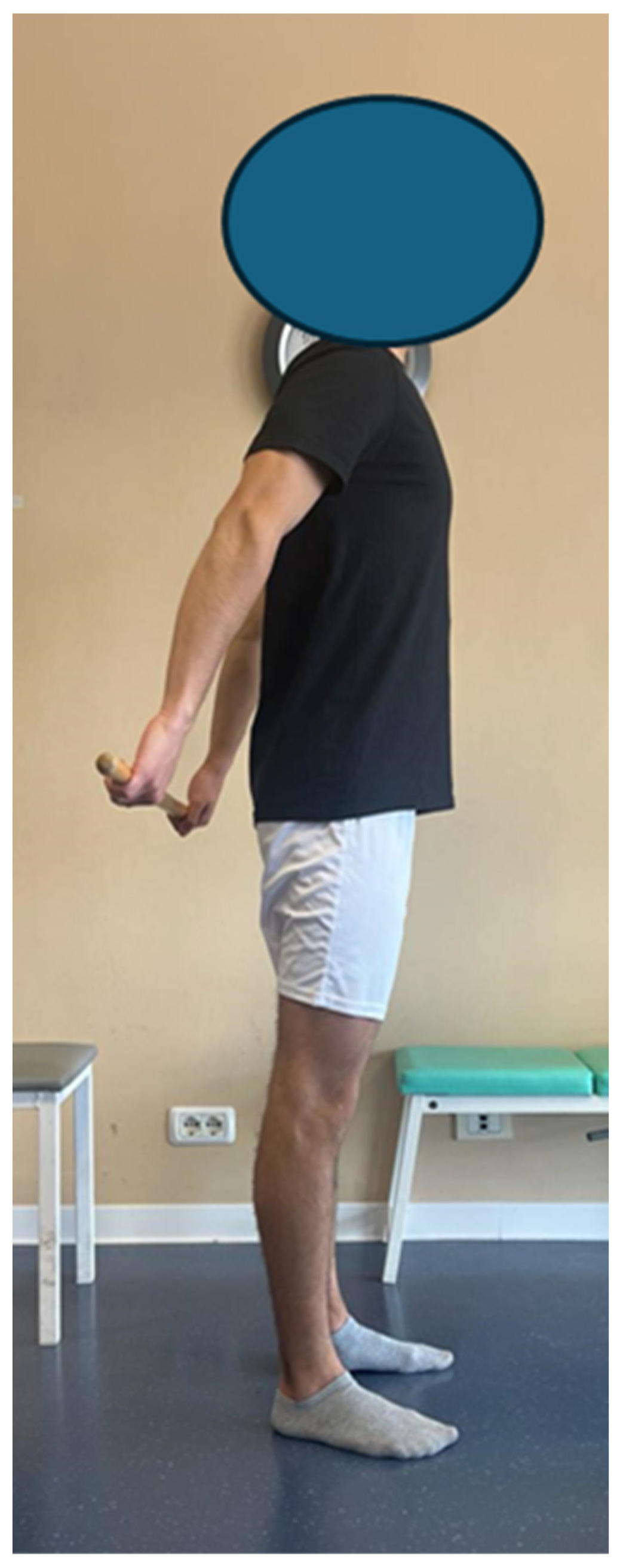

- Therapeutic exercise for ROM recovery and motor pattern: In combination with pain modulation techniques, therapeutic exercise was used, without overloads, to recover ROM and motor patterns. To this end, for example, exercises with a stick were used to recover flexion and abduction, as well as sliding exercises on the board and then against the wall. The exercises were used for the first 20 sessions, increasing the number of repetitions based on the pain perceived during the exercise (we accepted exercises that did not exceed an NPRS of 3/10) and that had a moderate intensity (perceived exertion ratings between 12 and 14 on the Borg scale).

- Open and closed kinetic chain exercises with a progression of intensity, frequency, time under tension, and load parameters: Open and closed kinetic chain exercises were used, initially considering the use of low loads (30% of 1RPM) and a high TUT (4 s for the concentric phase and 4 s for the eccentric phase), considering the same parameters used for short-term therapeutic exercise (NPRS values not exceeding 3/10 and Borg scale between 12 and 14). After approximately 10 sessions, we proceeded with the implementation of loads (up to 60% of 1RPM) and a lower TUT (2 s for the concentric phase and 2 s for the eccentric phase), using an NPRS not exceeding 3 as a parameter/10 and a Borg scale not exceeding 18–20.

- Joint position sense exercise for the upper limb: Exercises were used to improve the sense of position using a laser pointer placed first on the shoulder, then on the elbow, and finally on the hand, requiring the patient to follow paths set up on the wall.

- Exercises using TRX to improve target muscle activation: During these sessions, the patient expressed his desire to repeat some exercises that were part of his routine prior to the acute event. The TRXs were then used to reproduce some exercises that the patient previously performed in the gym to activate the posterior muscles of the back.

- Progressions for recovering the movements requested by the patient: push up, pull up, plank, side plank, deadlift, squat. The patient requested to perform the exercises he performed in his routine for his sport (bodybuilding) under the supervision of the physiotherapist. The patient was then supervised and instructed as regarded the exercises indicated.

References

- Cornea, A.; Lata, I.; Simu, M.; Rosca, E.C. Parsonage-Turner Syndrome Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsonage, M.J.; Aldren Turner, J.W. Neuralgic Amyotrophy; the Shoulder-Girdle Syndrome. Lancet 1948, 1, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greis, A.C.; Petrin, Z.; Gupta, S.; Magdalia, P.B. Neuralgic Amyotrophy. Brain Nerve 2014, 66, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, M.Z.; Haiy, A.U.; Bajwa, M.H.; Abeer, H.; Mustafa, B.; Ameer, F.; Amjad, Z.; Rehman, A.U. Association of Parsonage-Turner Syndrome with COVID-19 Infection and Vaccination: A Systematic Review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 03000605231187939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, J.H.; Radecki, J. Parsonage-Turner Syndrome. HSS J. 2010, 6, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alfen, N.; Van Engelen, B.G.M. The Clinical Spectrum of Neuralgic Amyotrophy in 246 Cases. Brain 2006, 129, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, J.J.J.; Groothuis, J.T.; Van Alfen, N. Neuralgic Amyotrophy: An Update on Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment. Muscle Nerve 2016, 53, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cup, E.H.; Ijspeert, J.; Janssen, R.J.; Bussemaker-Beumer, C.; Jacobs, J.; Pieterse, A.J.; Van Der Linde, H.; Van Alfen, N. Residual Complaints after Neuralgic Amyotrophy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, R.M.J.; Lustenhouwer, R.; Cup, E.H.C.; Van Alfen, N.; Ijspeert, J.; Helmich, R.C.; Cameron, I.G.M.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Van Engelen, B.G.M.; Graff, M.J.L.; et al. Effectiveness of an Outpatient Rehabilitation Programme in Patients with Neuralgic Amyotrophy and Scapular Dyskinesia: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2023, 94, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lustenhouwer, R.; Cameron, I.G.M.; van Alfen, N.; Toni, I.; Geurts, A.C.H.; van Engelen, B.G.M.; Groothuis, J.T.; Helmich, R.C. Cerebral Adaptation Associated with Peripheral Nerve Recovery in Neuralgic Amyotrophy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurorehabil. Neural. Repair. 2023, 37, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, D.S.; Barber, M.S.; Kienle, G.S.; Aronson, J.K.; von Schoen-Angerer, T.; Tugwell, P.; Kiene, H.; Helfand, M.; Altman, D.G.; Sox, H.; et al. CARE Guidelines for Case Reports: Explanation and Elaboration Document. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 89, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, W.B.; Uhl, T.L.; Maddux, J.W.Q.; Brooks, P.V.; Zeller, B.; McMullen, J. Qualitative Clinical Evaluation of Scapular Dysfunction: A Reliability Study. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2002, 11, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miccinilli, S.; Bravi, M.; Morrone, M.; Santacaterina, F.; Stellato, L.; Bressi, F.; Sterzi, S. A Triple Application of Kinesio Taping Supports Rehabilitation Program for Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2018, 20, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJspeert, J.; Janssen, R.M.J.; van Alfen, N. Neuralgic Amyotrophy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2021, 34, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alfen, N.; Van Eijk, J.J.J.; Ennik, T.; Flynn, S.O.; Nobacht, I.E.G.; Groothuis, J.T.; Pillen, S.; Van De Laar, F.A. Incidence of Neuralgic Amyotrophy (Parsonage Turner Syndrome) in a Primary Care Setting--a Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meixedo, S.; Correia, M.; Machado Lima, A.; Carneiro, I. Parsonage-Turner Syndrome Post-COVID-19 Oxford/AstraZeneca Vaccine Inoculation: A Case Report and Brief Literature Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e34710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J. Frozen Shoulder Contracture Syndrome—Aetiology, Diagnosis and Management. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.B.Y.; Pua, P.Y.; How, C.H. Physical Therapy in the Management of Frozen Shoulder. Singap. Med. J. 2017, 58, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B.; Shah, T.; Bajaj, G.; Hodde, M.; Popescu, A. The Importance of Differentiating Parsonage-Turner Syndrome From Cervical Radiculopathy: A Case Report. Cureus 2022, 14, e28723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolny, T.; Glibov, K.; Granek, A.; Linek, P. Ultrasound Diagnostic and Physiotherapy Approach for a Patient with Parsonage-Turner Syndrome-A Case Report. Sensors 2023, 23, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coratella, G. Appropriate Reporting of Exercise Variables in Resistance Training Protocols: Much More than Load and Number of Repetitions. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcleod, J.C.; Currier, B.S.; Lowisz, C.V.; Phillips, S.M. The Influence of Resistance Exercise Training Prescription Variables on Skeletal Muscle Mass, Strength, and Physical Function in Healthy Adults: An Umbrella Review. J. Sport Health Sci. 2024, 13, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galindez-Ibarbengoetxea, X.; Setuain, I.; Andersen, L.L.; Ramírez-Velez, R.; González-Izal, M.; Jauregi, A.; Izquierdo, M. Effects of Cervical High-Velocity Low-Amplitude Techniques on Range of Motion, Strength Performance, and Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Review. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Timing | Short Term (within 1 Month) | Mid Term (within 3 Month) | Long Term (within 6 Month) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aims | Pain modulation and recovery of muscle strength | Complete recovery of muscle strength and movement patterns | Return to sport |

| Weekly sessions | 5 times a week | 3 times a week | 2 times a week |

| Treatments |

|

|

|

| Dynamometer Shoulder Tests | Affected Side [Right] | Healthy Side [Left] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 Months | 24 Months | 36 Months | 12 Months | 24 Months | 36 Months | |

| Flexion [N/Kg] | 0.88 | 1.08 | 1.28 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 1.13 |

| Extension [N/Kg] | 2.10 | 2.18 | 2.10 | 1.89 | 1.93 | 1.80 |

| Abduction [N/Kg] | 0.94 | 1.09 | 1.34 | 1.01 | 1.10 | 1.08 |

| Adduction [N/Kg] | 1.55 | 1.86 | 1.78 | 1.49 | 1.62 | 2.08 |

| Internal rotation [N/Kg] | 0.85 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.25 | 1.15 | 1.19 |

| External rotation [N/Kg] | 0.78 | 0.90 | 1.03 | 1.10 | 1.15 | 0.99 |

| DASH Section | 12 Months | 24 Months | 36 Months |

|---|---|---|---|

| DASH principal (%) | 64.2% | 45% | 21.7% |

| DASH optional (%) | 87.5% | 75% | 40.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santacaterina, F.; Bravi, M.; Maselli, M.; Bressi, F.; Sterzi, S.; Miccinilli, S. Multimodal Rehabilitation Management of a Misunderstood Parsonage–Turner Syndrome: A Case Report during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk9010037

Santacaterina F, Bravi M, Maselli M, Bressi F, Sterzi S, Miccinilli S. Multimodal Rehabilitation Management of a Misunderstood Parsonage–Turner Syndrome: A Case Report during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2024; 9(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk9010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantacaterina, Fabio, Marco Bravi, Mirella Maselli, Federica Bressi, Silvia Sterzi, and Sandra Miccinilli. 2024. "Multimodal Rehabilitation Management of a Misunderstood Parsonage–Turner Syndrome: A Case Report during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 9, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk9010037

APA StyleSantacaterina, F., Bravi, M., Maselli, M., Bressi, F., Sterzi, S., & Miccinilli, S. (2024). Multimodal Rehabilitation Management of a Misunderstood Parsonage–Turner Syndrome: A Case Report during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 9(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk9010037