Tiered Levels of Resting Cortisol in an Athletic Population. A Potential Role for Interpretation in Biopsychosocial Assessment?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment

2.2. Cortisol Measures

2.3. Measures of Stress, Optimism and Decision Making Skills

2.4. Data and Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Reliability of Cortisol Measures

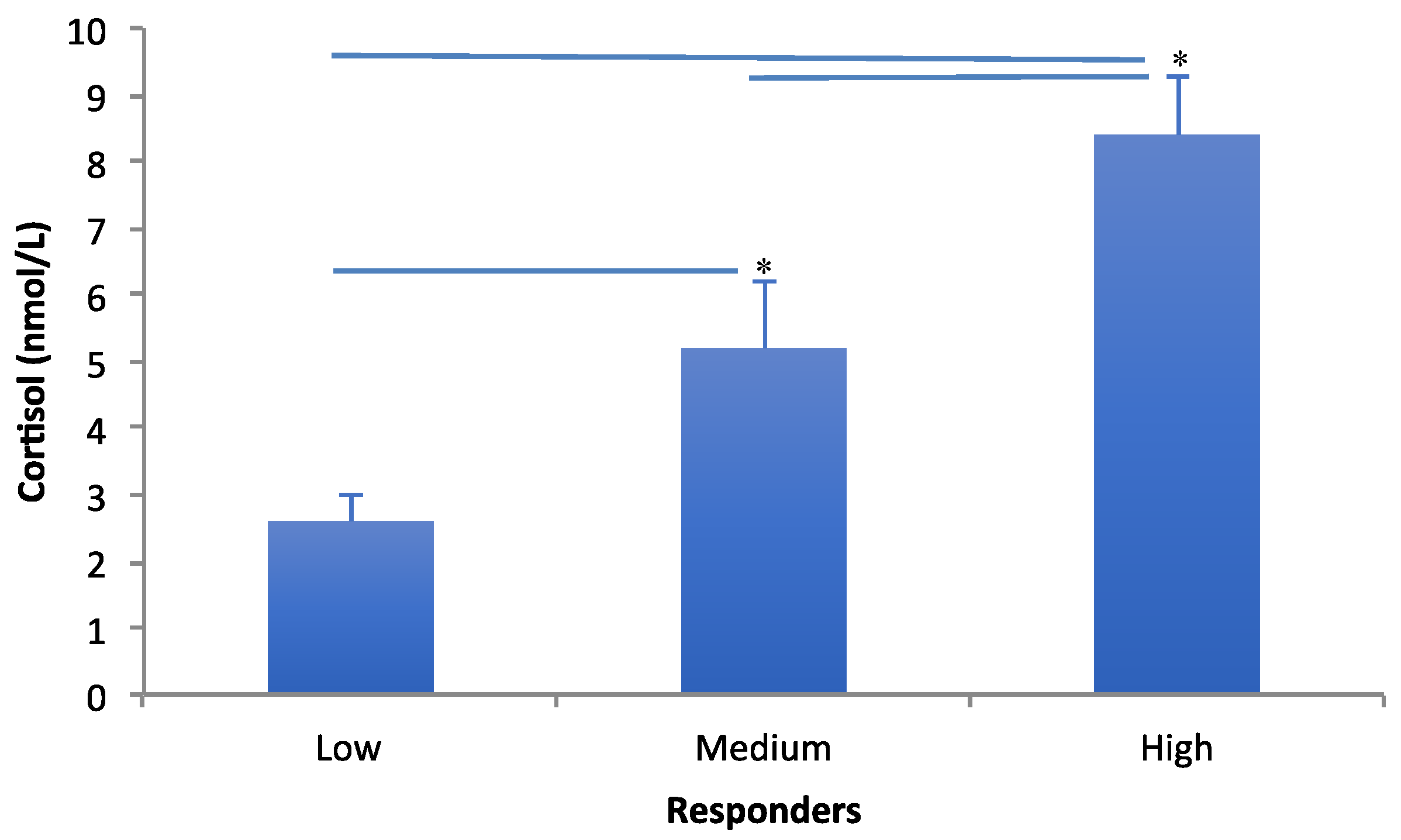

3.2. Cortisol Measures

3.3. Psychological Responses and Correlation to Cortisol

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stawski, R.S.; Cichy, K.E.; Piazza, J.R.; Almeida, D.M. Associations among daily stressors and salivary cortisol: Findings from the national study of daily experiences. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 2654–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staufenbiel, S.M.; Penninx, B.W.; Spijker, A.T.; Elzinga, B.M.; van Rossum, E.F. Hair cortisol, stress exposure, and mental health in humans: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 1220–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiksdal, A.; Hanlin, L.; Kuras, Y.; Gianferante, D.; Chen, X.; Thoma, M.V.; Rohleder, N. Associations between symptoms of depression and anxiety and cortisol responses to and recovery from acute stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 102, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellalieu, S.D.; Neil, R.; Hanton, S.; Fletcher, D. Competition stress in sport performers: Stressors experienced in the competition environment. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nippert, A.H.; Smith, A.M. Psychologic stress related to injury and impact on sport performance. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 19, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.R.; Sanderson, J. I’m going to instagram it! An analysis of athlete self-presentation on instagram. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2015, 59, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmigiani, S.; Dadomo, H.; Bartolomucci, A.; Brain, P.F.; Carbucicchio, A.; Costantino, C.; Ferrari, P.F.; Palanza, P.; Volpi, R. Personality traits and endocrine response as possible asymmetry factors of agonistic outcome in karate athletes. Aggress. Behav. Off. J. Int. Soc. Res. Aggress. 2009, 35, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, A.L.; Hess, D.E.; Edenborn, S.; Ubinger, E.; Carrillo, A.E.; Appasamy, P.M. Elevated salivary iga, decreased anxiety, and an altered oral microbiota are associated with active participation on an undergraduate athletic team. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 169, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondino, N.; Lanati, N.; Giudici, S.; Arpesella, M.; Roncarolo, F.; Vandoni, M. Testosterone level and its relationship with outcome of sporting activity. J. Men’s Health 2013, 10, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rist, B.; Pearce, A.J. Determining factors related to increased cortisol levels in australian rules football players. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, J.; Hazell, G.; Jehanli, A. Investigating a dual siga and alpha-amylase point of care test in the sporting environment. In Proceedings of the 12th ISEI Symposium, Vienna, Austria, 6–9 July 2015; The International Society of Exercise Immunology: Vienna, Austria, 2015; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. Perceived stress scale. In Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists; Cohen, S., Kessler, R.C., Gordon, L.U., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 235–283. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the life orientation test. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J. The raven’s progressive matrices: Change and stability over culture and time. Cogn. Psychol. 2000, 41, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, J.P. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the sem. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lupien, S.J.; Seguin, F. How to Measure Stress in Humans; Centre of Studies on Human Stress: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ivković, N.; Božović, Đ.; Račić, M.; Popović-Grubač, D.; Davidović, B. Biomarkers of stress in saliva. Acta Fac. Med. 2015, 32, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmaoui, B.; Touitou, Y. Reproducibility of the circadian rhythms of serum cortisol and melatonin in healthy subjects: A study of three different 24-h cycles over six weeks. Life Sci. 2003, 73, 3339–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Hellhammer, D.H. Salivary cortisol. In Psychoneuroendocrinology; FInk, G., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 379–383. [Google Scholar]

- Young, A.H. Cortisol in mood disorders. Stress 2004, 7, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parent-Lamarche, A.; Marchand, A. The moderating role of personality traits in the relationship between work and salivary cortisol: A cross-sectional study of 401 employees in 34 canadian companies. BMC Psychol. 2015, 3, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Mackinnon, A.; Batterham, P.J.; Stanimirovic, R. The mental health of australian elite athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblet, A.J.; Gifford, S.M. The sources of stress experienced by professional australian footballers. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2002, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddock-Hudson, M.; O’Halloran, P.; Murphy, G. Exploring psychological reactions to injury in the australian football league (afl). J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2012, 24, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Test 1 (nmol/L) | Test 2 (nmol/L) | Mean (nmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 8.7 |

| 2 | 4.9 | 7.2 | 6.1 |

| 3 | 8.9 | 6.6 | 7.8 |

| 4 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 2.9 |

| 5 | 2.7 | 6.0 | 4.4 |

| 6 | 10.0 | 7.4 | 8.7 |

| 7 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| 8 | 2.9 | 5.5 | 4.2 |

| 9 | 10.2 | 7.3 | 8.8 |

| 10 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.9 |

| 11 | 4.7 | 3.0 | 3.9 |

| 12 | 1.9 | 7.6 | 4.8 |

| 13 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 9.9 |

| 14 | 5.8 | 3.9 | 4.9 |

| 15 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 6.5 |

| 16 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 7.4 |

| 17 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 |

| 18 | 7.6 | 4.0 | 5.8 |

| 19 | 7.8 | 9.6 | 8.7 |

| 20 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| 21 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| 22 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 3.9 |

| Mean (±SD) | 5.9 (±2.4) | 6.0 (±2.4) | 5.9(±2.4) |

| Optimism (0–24) | Stress (0–40) | Decision Making (0–60) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | 10 | 51 |

| 2 | 9 | 13 | 48 |

| 3 | 11 | 14 | 35 |

| 4 | 11 | 15 | 48 |

| 5 | 15 | 19 | 50 |

| 6 | 11 | 17 | 45 |

| 7 | 11 | 19 | 43 |

| 8 | 10 | 23 | 43 |

| 9 | 9 | 22 | 28 |

| 10 | 9 | 23 | 35 |

| 11 | 12 | 18 | 53 |

| 12 | 14 | 21 | 53 |

| 13 | 8 | 19 | 45 |

| 14 | 10 | 18 | 31 |

| 15 | 10 | 15 | 49 |

| 16 | 13 | 19 | 47 |

| 17 | 15 | 16 | 47 |

| 18 | 8 | 20 | 41 |

| 19 | 12 | 19 | 49 |

| 20 | 13 | 16 | 45 |

| 21 | 11 | 22 | 37 |

| 22 | 10 | 14 | 50 |

| Mean (±SD) | 11.0 (±2.0) | 17.8 (±3.4) | 44.2(±7.0) |

| Optimism | Stress | Decision Making | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s r 1 | 0.236 | 0.051 | 0.195 |

| p Value | 0.291 | 0.821 | 0.385 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rist, B.; Pearce, A.J. Tiered Levels of Resting Cortisol in an Athletic Population. A Potential Role for Interpretation in Biopsychosocial Assessment? J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2019, 4, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4010008

Rist B, Pearce AJ. Tiered Levels of Resting Cortisol in an Athletic Population. A Potential Role for Interpretation in Biopsychosocial Assessment? Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2019; 4(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleRist, Billymo, and Alan J. Pearce. 2019. "Tiered Levels of Resting Cortisol in an Athletic Population. A Potential Role for Interpretation in Biopsychosocial Assessment?" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 4, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4010008

APA StyleRist, B., & Pearce, A. J. (2019). Tiered Levels of Resting Cortisol in an Athletic Population. A Potential Role for Interpretation in Biopsychosocial Assessment? Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 4(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4010008