What Factors Predict Falls in Older Adults Living in Nursing Homes: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Gait Speed Measurement

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Administration on Aging. A Profile of Older Americans; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Fuller, G.F. Falls in the elderly. Am. Fam. Phys. 2000, 61, 2159–2168. [Google Scholar]

- White, B.L.; Fisher, W.D.; Laurin, C.A. Rate of mortality for elderly patients after fracture of the hip in the 1980’s. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1987, 69, 1335–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.A.; Corso, P.S.; Finkelstein, E.A.; Miller, T.R. The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Inj. Prev. 2006, 12, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, E.R.; Stevens, J.A.; Lee, R. The direct costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults—United States. J. Saf. Res. 2016, 58, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, L.Z.; Josephson, K.R.; Robbins, A.S. Falls in the nursing home. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, M.L.; Pittaway, J.K.; Cuisick, I.; Rattray, M.; Ahuja, K.D.K. Age-related changes in physical fall risk factors: Results from a 3 year follow-up of community dwelling older adults in Tasmania, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 5989–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ensrud, K.E.; Ewing, S.K.; Taylor, B.C. Frailty and risk of falls, fracture, and mortality in older women: The study of osteoporotic fractures. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfken, C.L.; Lach, H.W.; Birge, S.J.; Miller, J.P. The prevalence and correlates of fear of falling in elderly persons living in the community. Am. J. Public Health 1994, 84, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howland, J.; Peterson, E.W.; Levin, W.C.; Fried, L.; Pordon, D.; Bak, S. Fear of falling among the community-dwelling elderly. J. Aging Health 1993, 5, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, P.T.M.; Meulenberg, O.G.R.M.; Van de Sande, H.J.; Habbema, J.D.F. Falls in dementia patients. Gerontologist 1993, 33, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.A.; Thomas, K.; Teh, L.; Greenspan, A.I. Unintentional fall injuries associated with walkers and canes in older adults treated in US emergency departments. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 1464–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostir, G.V.; Berges, I.; Kuo, Y.F.; Goodwin, J.S.; Ottenbacher, K.J.; Guralnik, J.M. Assessing gait speed in acutely ill older patients admitted to an acute care for elders hospital unit. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.E.; Perera, S.; Roumani, Y.F.; Chandler, J.M.; Studenski, S.A. Improvement in usual gait speed predicts better survival in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 1727–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, E.E.; Nguyen, T.H.; Shaha, M.; Wenzel, J.A.; DeForge, B.R.; Spellbring, A.M. Person-environment interactions contributing to nursing home resident falls. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2009, 2, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, L.A.; Musiol, R.J.; Witham, E.K.; Metter, E.J. Falls in young, middle-aged and older community dwelling adults: Perceived cause, environmental factors and injury. BMC Public Health 2005, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, P.B.; Gideon, P.; Cost, T.W.; Milam, A.B.; Ray, W.A. Antidepressants and the risk of falls among nursing home residents. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, J.A.; Sogolow, E.D. Gender differences for non-fatal unintentional fall related injuries among older adults. Inj. Prev. 2005, 11, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursing Home Data Compendium 2013 Edition; U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013.

- Friedman, S.M.; Munoz, B.; West, S.K.; Rubin, G.S.; Fried, L.P. Falls and fear of falling: Which comes first? A longitudinal prediction model suggests strategies for primary and secondary prevention. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 50, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.L.; Dubin, J.A.; Gill, T.M. The development of fear of falling among community-living older women: Predisposing factors and subsequent fall events. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, M943–M947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D. Fear of falling in older adults: Comprehensive review. Asian Nurs. Res. (Korean Soc. Nurs. Sci.) 2008, 2, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, S.; Rozzini, R.; Boffelli, S.; Frisoni, G.B.; Trabucchi, M. Fear of falling in nursing home patients. Gerontology 1994, 40, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, B.A.; Bhat, G.; Stevens, J.; Bergen, G. Assistive device use and mobility-related factors among adults aged ≥ 65years. J. Saf. Res. 2015, 55, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, S.W.; Gopaul, K.; Odasso, M.M.M. The role of cognitive impairment in fall risk among older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2012, 41, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dementia Care Practice Recommendations for End-of-Life Care; Alzheimer’s Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007; Volume 1, Available online: https://www.alz.org/national/documents/release_082807_dcrecommends.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2014).

- Perkins, C. Dementia and falling. N. Z. Fam. Phys. 2008, 35, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcott, J.C.; Richardson, K.J.; Wiens, M.O. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 1952–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, P.; Chen, H.; Sherer, J.T.; Aparasu, R.R. Use of antipsychotics among elderly nursing home residents with dementia in the US. Drugs Aging 2009, 26, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aka, P.C.; Deason, L.M.; Hammond, A. Political factors and enforcement of the nursing home regulatory regime. J. Law Health 2011, 24, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Purser, J.L.; Weinberger, M.; Cohen, H.J.; Pieper, C.F. Walking speed predicts health status and hospital costs for frail elderly male veterans. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2005, 42, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Speechley, M.; Ginter, S.F. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 1701–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; Schapira, M.; Soriano, E.R. Gait velocity as a single predictor of adverse events in healthy seniors aged 75 years and older. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2005, 60, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, T.M.; Hacker, T.A.; Mollinger, L. Age-and gender-related test performance in community-dwelling elderly people: Six-minute walk test, Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up & Go Test, a nd gait speeds. Phys. Ther. 2002, 82, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cesari, M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Penninx, B.W.; Nicklas, B.J.; Simonsick, E.M.; Newman, A.B.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Brach, J.S.; Satterfield, S.; Bauer, D.C.; et al. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people—Results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 1675–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studenski, S.; Perera, S.; Wallace, D.; Chandler, J.M.; Duncan, P.W.; Rooney, E.; Fox, M.; Guralnik, J.M. Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kan, G.A.; Rolland, Y.; Andrieu, S.; Bauer, J.; Beauchet, O.; Bonnefoy, M.; Nourhashemi, F. Gait speed at usual pace as a predictor of adverse outcomes in community-dwelling older people an International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (IANA) Task Force. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, N.M.; Kuys, S.S.; Klein, K. Gait speed as a measure in geriatric assessment in clinical settings: A systematic review. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subject No. | Falls | Antidepressant | Antianxiety | Antihypertensive | Diuretic | Β-Blockers | Statins | Antipsychotic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | × | × | |||||

| 2 | 3 | × | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | × | × | × | ||||

| 4 | 1 | × | ||||||

| 5 | 0 | × | ||||||

| 6 | 0 | |||||||

| 7 | 6 | × | × | |||||

| 8 | 0 | × | × | |||||

| 9 | 1 | × | × | |||||

| 10 | 0 | × | × | × | × | |||

| 11 | 0 | |||||||

| 12 | 0 | × | × | |||||

| 13 | 0 | × | × | |||||

| 14 | 0 | × | × | |||||

| 15 | 3 | × | × | |||||

| 16 | 0 | × |

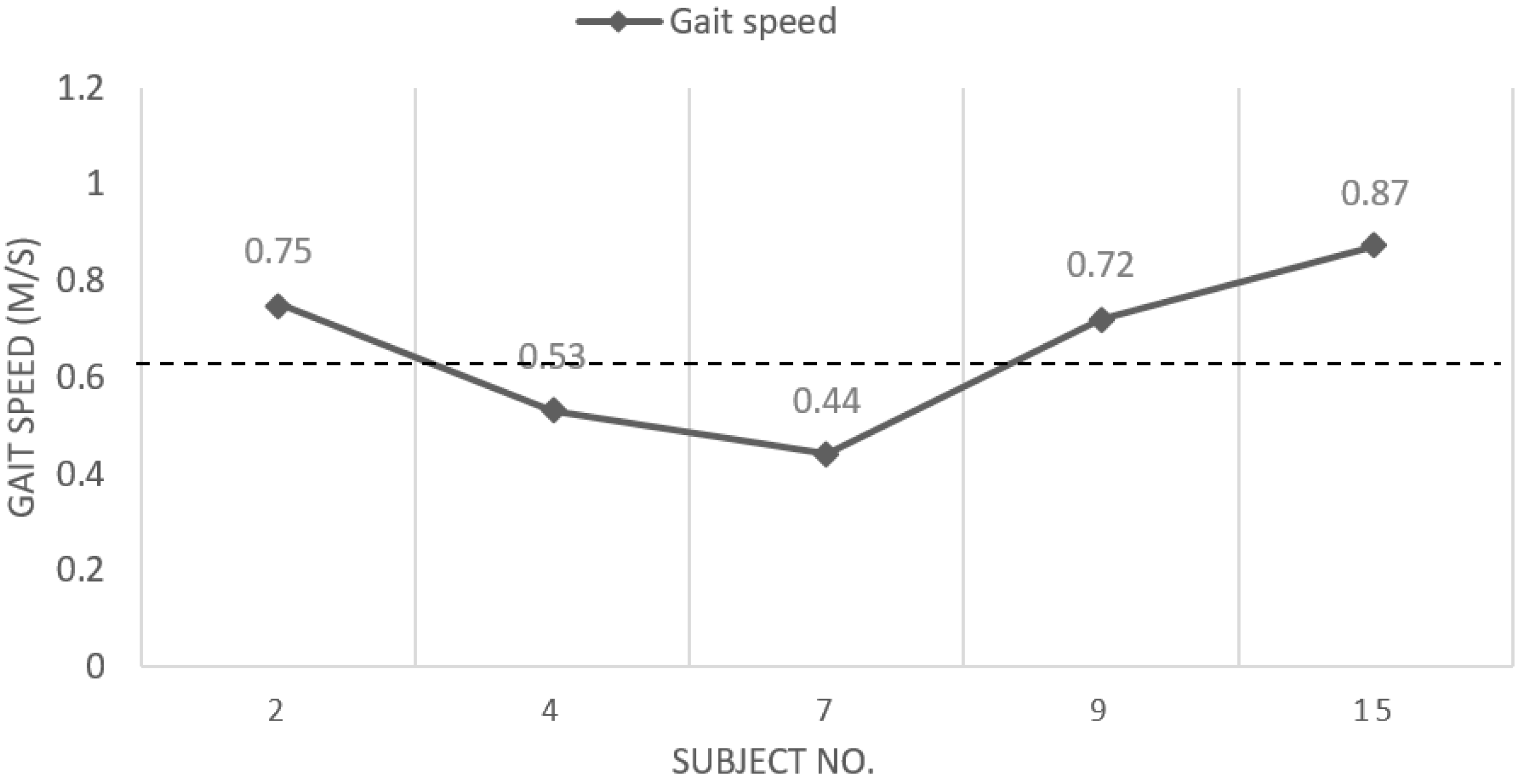

| No. | Sex | Date | Age | Time | Gait Speed (m/s) | Mobility Aid | Fear of Falling | Self-Rated Health | Falls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 7/1/2015 | 65 | 17.47 | 0.70 | walker | no | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 6/25/2015 | 70 | 16.35 | 0.75 | walker | yes | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | F | 6/25/2015 | 70 | 10.84 | 1.12 | none | no | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | F | 6/25/2015 | 85 | 23.06 | 0.53 | walker | no | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | M | 6/30/2015 | 90 | 20.15 | 0.61 | walker | no | 2 | 0 |

| 6 | F | 7/30/2015 | 90 | 23.42 | 0.52 | walker | no | 2 | 0 |

| 7 | M | 8/18/2015 | 90 | 27.66 | 0.44 | walker | no | 3 | 6 |

| 8 | F | 6/25/2015 | 78 | 15.05 | 0.81 | none | no | 3 | 0 |

| 9 | F | 9/24/2015 | 87 | 16.88 | 0.72 | none | no | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | F | 10/1/2015 | 83 | 20.3 | 0.60 | walker | yes | 3 | 0 |

| 11 | F | 10/15/2015 | 77 | 22.46 | 0.54 | none | no | 2 | 0 |

| 12 | F | 9/21/2015 | 73 | 20.01 | 0.61 | none | no | 3 | 0 |

| 13 | F | 11/9/2015 | 66 | 22.18 | 0.55 | walker | yes | 3 | 0 |

| 14 | M | 7/11/2015 | 85 | 19.46 | 0.63 | walker | yes | 3 | 0 |

| 15 | F | 8/15/15 | 74 | 13.97 | 0.87 | none | no | 3 | 3 |

| 16 | F | 11/9/2015 | 91 | 30.53 | 0.40 | walker | yes | 4 | 0 |

| Variable | % (n) | Range | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 25% (4) | ||

| Female | 75% (12) | ||

| Age | 65–91 | 79.625 | |

| Mobility aid | |||

| Yes | 62.5% (10) | ||

| No | 37.5% (6) | ||

| Fear of falling | |||

| Yes | 31.25% (5) | ||

| No | 68.75% (11) | ||

| Self-rated health | |||

| Fair | 18.75% (3) | ||

| Good | 25.00% (4) | ||

| Very Good | 50.00% (8) | ||

| Excellent | 6.25% (1) | ||

| Cognitive | |||

| Diagnosed | 50% (8) | ||

| No | 50% (8) | ||

| Falls—reported and recorded | Total 5 | ||

| None | 68.75% (11) | ||

| One | 12.50% (2) | ||

| Three | 12.50% (2) | ||

| Six | 6.25% (1) | ||

| Environmental cause of fall | |||

| Yes | 100% (5/5) | ||

| No | 0% (0/5) | ||

| Medications | |||

| Antipsychotics | 43.75% (7) | ||

| Antidepressants | 25% (4) |

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Time for walking 12.19 m | s |

| Maximum | 30.53 |

| Minimum | 10.94 |

| Gait speed | m/s |

| Fastest | 1.12 |

| Slowest | 0.40 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.464 | 1.000 | 0.080707–98.16351 |

| Age | 0.866 | 1.000 | 0.0640751–14.65901 |

| Gait speed | 0.977 | 0.846 | 0.7774365–1.211467 |

| Mobility aid | 0.866 | 1.000 | 0.0640751–14.65901 |

| Fear of falling | 0.459 | 0.967 | 0.0071286–7.359933 |

| Self-rated health | 0.438 | 0.315 | 0.080355–1.763968 |

| Cognitive status | 6.157 | 0.282 | 0.4139234–392.7872 |

| Environmental cause of fall | 64.003 | 0.0005 * | 5.566613 ± Inf |

| Medications | 1 | - |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Datta, A.; Datta, R.; Elkins, J. What Factors Predict Falls in Older Adults Living in Nursing Homes: A Pilot Study. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2019, 4, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4010003

Datta A, Datta R, Elkins J. What Factors Predict Falls in Older Adults Living in Nursing Homes: A Pilot Study. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2019; 4(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleDatta, Aditi, Rahul Datta, and Jeananne Elkins. 2019. "What Factors Predict Falls in Older Adults Living in Nursing Homes: A Pilot Study" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 4, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4010003

APA StyleDatta, A., Datta, R., & Elkins, J. (2019). What Factors Predict Falls in Older Adults Living in Nursing Homes: A Pilot Study. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 4(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4010003