Public Safety Heroes (PUSH) Workout: Task-Specific High-Intensity Functional Training for Emergency Readiness in Fire and Police—Proof of Concept

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

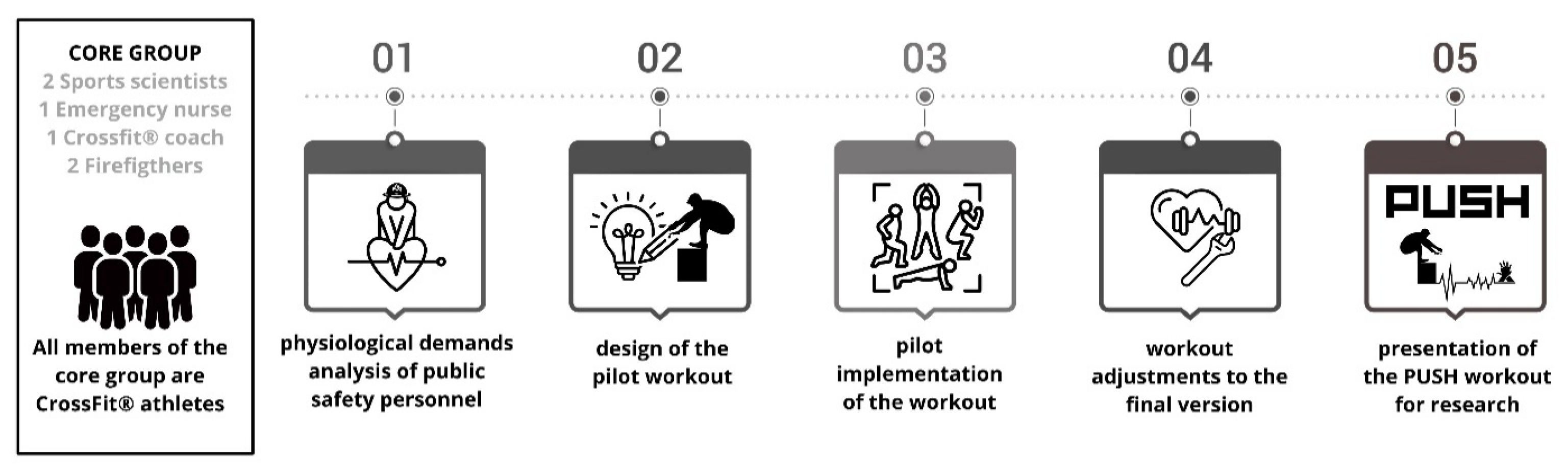

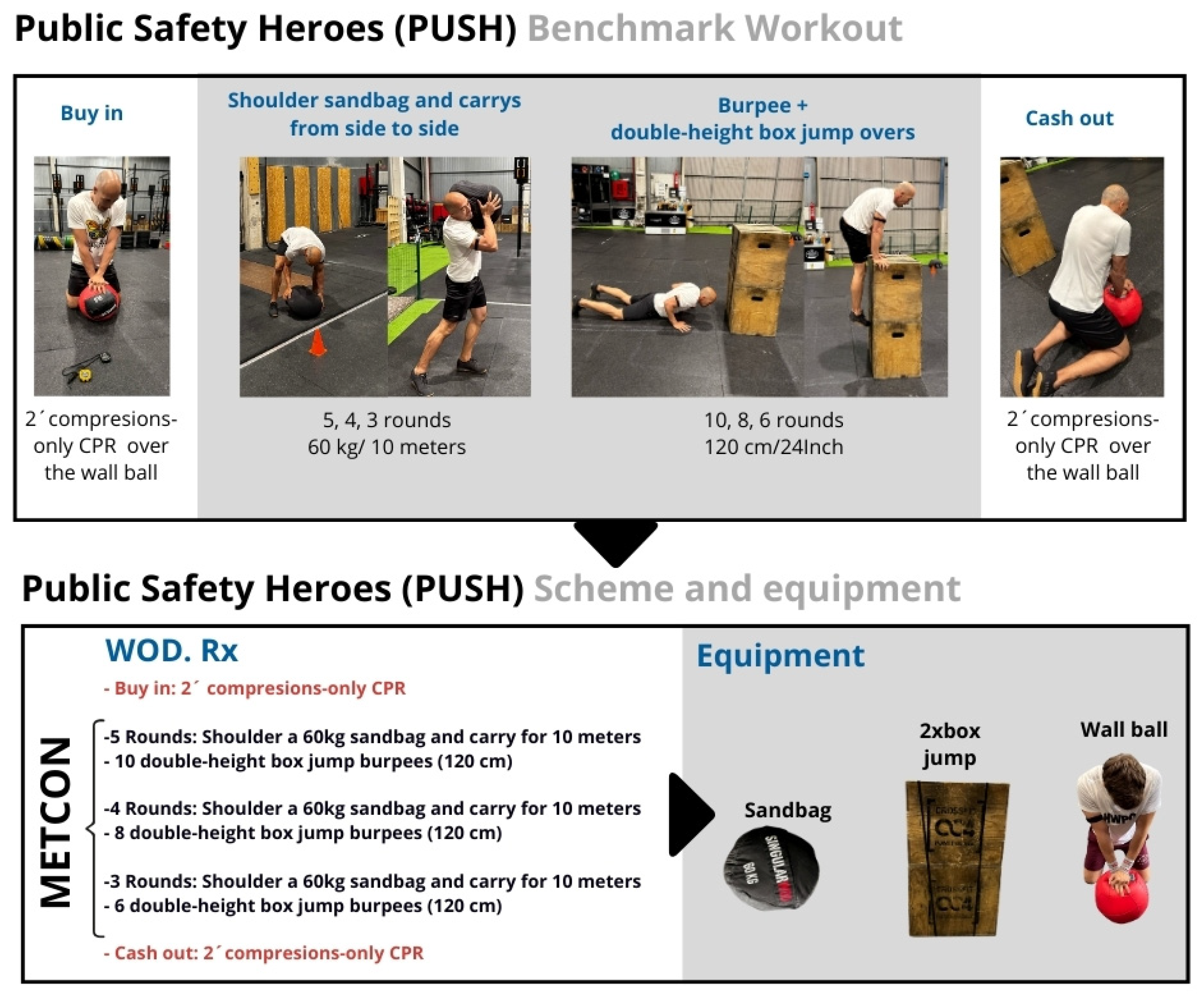

2.2. Training Design

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Procedures and Variables

2.4.1. Procedures

2.4.2. Variables

- Routine time (WOD for time): Two measures were collected in this section: (a) total WOD time (including compressions-only CPR) and (b) METCON time. This variable was recorded in seconds (s) using an arm sensor (Polar Verity Sense®, Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland).

- Lactate: Capillary blood samples were collected from the fingertip using a portable analyzer (LactateScout, SensLab GmbH, Leipzig, Germany), with results expressed in mmol·L−1, immediately before the first 2 min compressions-only CPR bout and 1 min after the second 2 min compressions-only CPR bout.

- Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE): RPE was recorded at five time points using the modified Borg 0–10 scale: (1) before starting the session, (2) immediately after the first CPR bout, (3) after completing the WOD, (4) after the second CPR bout, and (5) during the final lactate sampling (3 min post-WOD). This enabled tracking of perceived effort throughout the protocol.

- Heart rate (HR): HR was continuously recorded using an optical arm sensor (Polar Verity Sense®, Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland). Mean and peak HR values were extracted for analysis.

- Compressions-only CPR quality in percentage (%): CC were performed on a 6 kg medicine ball, with a Laerdal CPRmeter (Stavanger, Norway) placed on top to record compression depth, rate, and full release in real time. The same wall ball and setup were used for all participants to ensure standardization. Athletes received real-time feedback on their CC to standardize effort, aiming to maintain the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation, Adult Basic Life Support 2025 (ERCGR2025) [16] recommendations for CC: a compression rate of 100–120 per minute, a depth of 5–6 cm, and complete chest recoil.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Routine Time (WOD for Time)

3.2. Physiological Variables (Table 1)

3.2.1. Lactate Measurements (mmol·L−1)

| Variables | Public Safety (n = 15) Median (IQR) | Police (n = 8) Median (IQR) | Fire (n = 7) Median (IQR) | p-Value (ES) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate (mmol·L−1) | Baseline lactate | 2.2 (1.9–3.1) | 1.95 (1.2–2.5) | 3.0 (2.4–3.3) | 0.06 (1.05) * |

| Post-WOD lactate | 14.8 (13.8–15.4) | 14.2 (13.1–14.6) | 15.0 (14.9–17.1) | 0.16 (0.78) * | |

| Lactate comparison | <0.001 (4.34) † | <0.001 (4.16) † | <0.001 (4.48) † | ||

| Baseline (a) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.61 (0.27) * | |

| RPE (0–10 scale) | Post-BUY-IN (b) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 5 (3–6) | 0.65 (0.24) * |

| Post-WOD (c) | 8 (8–9) | 8 (8–9) | 8 (8–9) | 0.79 (0.07) ỻ | |

| Post-CASH-OUT (d) | 7 (7–8) | 8 (7–9) | 7 (7–8) | 0.71 (0.10) ỻ | |

| 3 min post-WOD (e) | 5 (5–6) | 5 (5–7) | 5 (5–6) | 0.61 (0.13) ỻ | |

| RPE comparison | a vs. c < 0.001 (1.71) ǂ a vs. d < 0.001 (1.42) ǂ a vs. e = 0.022 (0.79) ǂ b vs. c = 0.008 (0.86) ǂ b vs. d < 0.001 (1.16) ǂ c vs. e = 0.003 (0.92) ǂ | a vs. c < 0.001 (1.68) ǂ a vs. d < 0.001 (1.45) ǂ b vs. c = 0.012 (1.15) ǂ | a vs. c < 0.001 (1.76) ǂ a vs. d = 0.003 (1.37) ǂ b vs. c = 0.018 (1.18) ǂ | ||

| Mean HR | 152 (145–159) | 152 (140–161) | 157 (150–159) | 0.80 (0.13) * | |

| HR | Maximal HR | 170 (163–175) | 172 (163–179) | 170 (161–172) | 0.51 (0.35) * |

3.2.2. Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE; 0–10 Scale)

3.2.3. Heart Rate (Beats per Minute, bpm)

3.3. Chest Compression Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maglione, M.A.; Chen, C.; Bialas, A.; Motala, A.; Chang, J.; Akinniranye, G.; Hempel, S. Stress control for military, law enforcement, and first responders: A systematic review. Rand Health Q. 2022, 9, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera-Campos, A.; Asensio-Lafuente, E.; Fraga-Sastrías, J.M. Análisis de la inclusión de la policía en la respuesta de emergencias al paro cardiorrespiratorio extrahospitalario. Salud Publica Mex. 2012, 54, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Salhi, R.A.; Hammond, S.; Lehrich, J.L.; O’Leary, M.; Kamdar, N.; Brent, C.; de Leon, C.F.M.; Mendel, P.; Nelson, C.; Forbush, B.; et al. The association of fire or police first responder initiated interventions with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival. Resuscitation 2022, 174, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.Q.; Clasey, J.L.; Yates, J.W.; Koebke, N.C.; Palmer, T.G.; Abel, M.G. Relationship of physical fitness measures vs. occupational physical ability in campus law enforcement officers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2340–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, A.; Karlsson, T.; Thorén, A.B.; Herlitz, J. Delay and performance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in surf lifeguards after simulated cardiac arrest due to drowning. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2011, 29, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobo-Vázquez, C.; De Blas, G.; García-Canas, P.; Del Carmen Gasco-García, M. Electrophysiology of muscle fatigue in cardiopulmonary resuscitation on manikin model. Anesth. Prog. 2018, 65, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min Ko, R.J.; Wu, V.X.; Lim, S.H.; San Tam, W.W.; Liaw, S.Y. Compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation in improving bystanders’ cardiopulmonary resuscitation performance: A literature review. Emerg. Med. J. 2016, 33, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bajić, S.; Veljović, D.; Bulajić, B.Đ. Impact of physical fitness on emergency response: A case study of factors that influence individual responses to emergencies among university students. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, M.P.; Priest, S.J.; Plume, R.C.; Wilson, E.E. Emergency first responders and professional wellbeing: A qualitative systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14649. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/22/14649 (accessed on 7 November 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvin, G.; Schram, B.; Orr, R.; Canetti, E.F.D. Occupation-Induced Fatigue and Impacts on Emergency First Responders: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudino, J.G.; Gabbett, T.J.; Bourgeois, F.; Souza, H.S.; Miranda, R.C.; Mezêncio, B.; Soncin, R.; Filho, C.A.C.; Bottaro, M.; Hernandez, A.J.; et al. CrossFit overview: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangine, G.T.; Stratton, M.T.; Almeda, C.G.; Roberts, M.D.; Esmat, T.A.; VanDusseldorp, T.A.; Feito, Y. Physiological differences between advanced CrossFit athletes, recreational CrossFit participants, and physically active adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0223548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maté-Muñoz, J.L.; Lougedo, J.H.; Barba, M.; Cañuelo-Márquez, A.M.; Guodemar-Pérez, J.; García-Fernández, P.; Lozano-Estevan, M.d.C.; Alonso-Melero, R.; Sanchez-Calabuig, M.A.; Ruiz-Lopez, M.; et al. Cardiometabolic and muscular fatigue responses to different CrossFit workouts. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2018, 17, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zarzosa-Alonso, F.; Alonso-Calvete, A.; Otero-Agra, M.; Fernández-Méndez, M.; Fernández-Méndez, F.; Martín-Rodríguez, F.; Barcala-Furelos, R.; Santos-Folgar, M. Foam roller post-high-intensity training for CrossFit athletes: Does it really help with recovery? J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handley, A.J.; Koster, R.; Monsieurs, K.; Perkins, G.D.; Davies, S.; Bossaert, L. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005: Section 2. Adult basic life support and use of automated external defibrillators. Resuscitation 2005, 67, S7–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.; Sakurai, T.; Scott, J.; Movshovich, J.; Dawes, J.J.; Lockie, R.; Schram, B. The use of fitness testing to predict occupational performance in tactical personnel: A critical review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7480. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/14/7480 (accessed on 7 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dominski, F.H.; Serafim, T.T.; Siqueira, T.C.; Andrade, A. Psychological variables of CrossFit participants: A systematic review. Sport Sci. Health 2021, 17, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fernández, J.; Sabido-Solana, R.; Moya, D.; Sarabia-Marín, J.M.; Moya-Ramón, M. Acute physiological responses during CrossFit workouts. Eur. J. Hum. Mov. 2015, 35, 114–124. Available online: https://eurjhm.com/index.php/eurjhm/article/view/362 (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Garber, C.E.; Blissmer, B.; Deschenes, M.R.; Franklin, B.A.; Lamonte, M.J.; Lee, I.M.; Nieman, D.C.; Swain, D.P. American College of Sports Medicine position stand: Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults—Guidance for prescribing exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, S.J.; Neyedly, T.J.; Horvey, K.J.; Benko, C.R. Do physiological measures predict selected CrossFit benchmark performance? Open Access J. Sports Med. 2015, 6, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa Neto, I.V.; de Sousa, N.M.F.; Neto, F.R.; Falk Neto, J.H.; Tibana, R.A. Time course of recovery following CrossFit Karen benchmark workout in trained men. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 899652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, L.; Dias, M.; Campos, Y.; Vieira, J.G.; Sant’Ana, L.; Telles, L.G.; Tavares, C.; Mazini, M.; Novaes, J.; Vianna, J. Physical and physiological predictors of FRAN CrossFit WOD athlete’s performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreker, J.D.; Grosicki, G.J. Physiological predictors of performance on the CrossFit “Murph” challenge. Sports 2020, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangine, G.T.; Cebulla, B.; Feito, Y. Normative values for self-reported benchmark workout scores in CrossFit practitioners. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelairas-Gómez, C.; Barcala-Furelos, R.; Szarpak, Ł.; García-García, Ó.; Paz-Domínguez, Á.; López-García, S.; Rodríguez-Núñez, A. The effect of strength training on quality of prolonged basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Kardiol. Pol. 2017, 75, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, G.D.; Stilley, J.D.; Franke, W.D. How does rescuer fitness affect the quality of prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation? Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2022, 26, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greif, R.; Lauridsen, K.G.; Djärv, T.; Ek, J.E.; Monnelly, V.; Monsieurs, K.G.; Nikolaou, N.; Olasveengen, T.M.; Semeraro, F.; Spartinou, A.; et al. European Resuscitation Council guidelines 2025 executive summary. Resuscitation 2025, 215, 109086. Available online: https://www.resuscitationjournal.com/article/S0300-9572(25)00282-5/fulltext (accessed on 22 December 2025). [CrossRef]

| Variables | Public Safety (n = 15) Median (IQR) | Police (n = 8) Median (IQR) | Fire (n = 7) Median (IQR) | p-Value (ES) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC with adequate depth | |||||

| BUY-IN | 99 (98–100) | 98 (96–99) | 99 (99–100) | 0.09 (0.45) ỻ | |

| CASH-OUT | 98 (98–99) | 98 (97–99) | 99 (98–99) | 0.054 (0.50) ỻ | |

| Depth comparison | 0.66 (0.11) χ | 0.68 (0.15) χ | 0.08 (0.65) χ | ||

| CC with adequate release | |||||

| BUY-IN | 89 (86–94) | 89 (86–90) | 96 (87–97) | 0.16 (0.36) ỻ | |

| CASH-OUT | 91 (89–95) | 90 (87–92) | 96 (90–98) | 0.13 (0.39) ỻ | |

| Release comparison | 0.034 (0.61) † | 0.12 (0.72) † | 0.29 (0.43) † | ||

| CC with adequate rate | |||||

| BUY-IN | 91 (88–95) | 89 (79–92) | 95 (91–97) | 0.020 (1.36) * | |

| CASH-OUT | 91 (86–96) | 86 (80–91) | 96 (94–98) | 0.002 (2.06) * | |

| Rate comparison | 0.72 (0.09) † | 0.81 (0.09) † | 0.11 (0.72) † | ||

| Compressions-only CPR quality | |||||

| BUY-IN | 93 (90–95) | 90 (88–93) | 96 (94–97) | 0.011 (0.66) ỻ | |

| CASH-OUT | 94 (90–96) | 91 (88–93) | 96 (95–97) | 0.016 (1.44) * | |

| Score comparison | 0.10 (0.43) χ | 0.36 (0.32) χ | 0.11 (0.70) † | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barcala-Furelos, R.; Zarzosa-Alonso, F.; Otero-Agra, M.; Fernández-Méndez, F.; Alonso-Calvete, A. Public Safety Heroes (PUSH) Workout: Task-Specific High-Intensity Functional Training for Emergency Readiness in Fire and Police—Proof of Concept. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2026, 11, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010060

Barcala-Furelos R, Zarzosa-Alonso F, Otero-Agra M, Fernández-Méndez F, Alonso-Calvete A. Public Safety Heroes (PUSH) Workout: Task-Specific High-Intensity Functional Training for Emergency Readiness in Fire and Police—Proof of Concept. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2026; 11(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarcala-Furelos, Roberto, Fernando Zarzosa-Alonso, Martín Otero-Agra, Felipe Fernández-Méndez, and Alejandra Alonso-Calvete. 2026. "Public Safety Heroes (PUSH) Workout: Task-Specific High-Intensity Functional Training for Emergency Readiness in Fire and Police—Proof of Concept" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 11, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010060

APA StyleBarcala-Furelos, R., Zarzosa-Alonso, F., Otero-Agra, M., Fernández-Méndez, F., & Alonso-Calvete, A. (2026). Public Safety Heroes (PUSH) Workout: Task-Specific High-Intensity Functional Training for Emergency Readiness in Fire and Police—Proof of Concept. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 11(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010060