Effects of Knee Sleeve Density on Theoretical Neuromuscular Capacities Derived from the Force–Velocity–Power Profile in the Back Squat

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample and Design

| Mean | SD | Max | Min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 25.13 | 2.39 | 30 | 22 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.60 | 6.28 | 92.00 | 70 |

| Height (m) | 1.73 | 0.07 | 1.93 | 1.65 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.70 | 2.23 | 31.83 | 23.41 |

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Back Squat Assessment

2.4. Data Processing and Construction of the Force–Velocity–Power Profile

2.5. Calculation of Theoretical Neuromuscular Capacities

2.6. Statistical Analysis

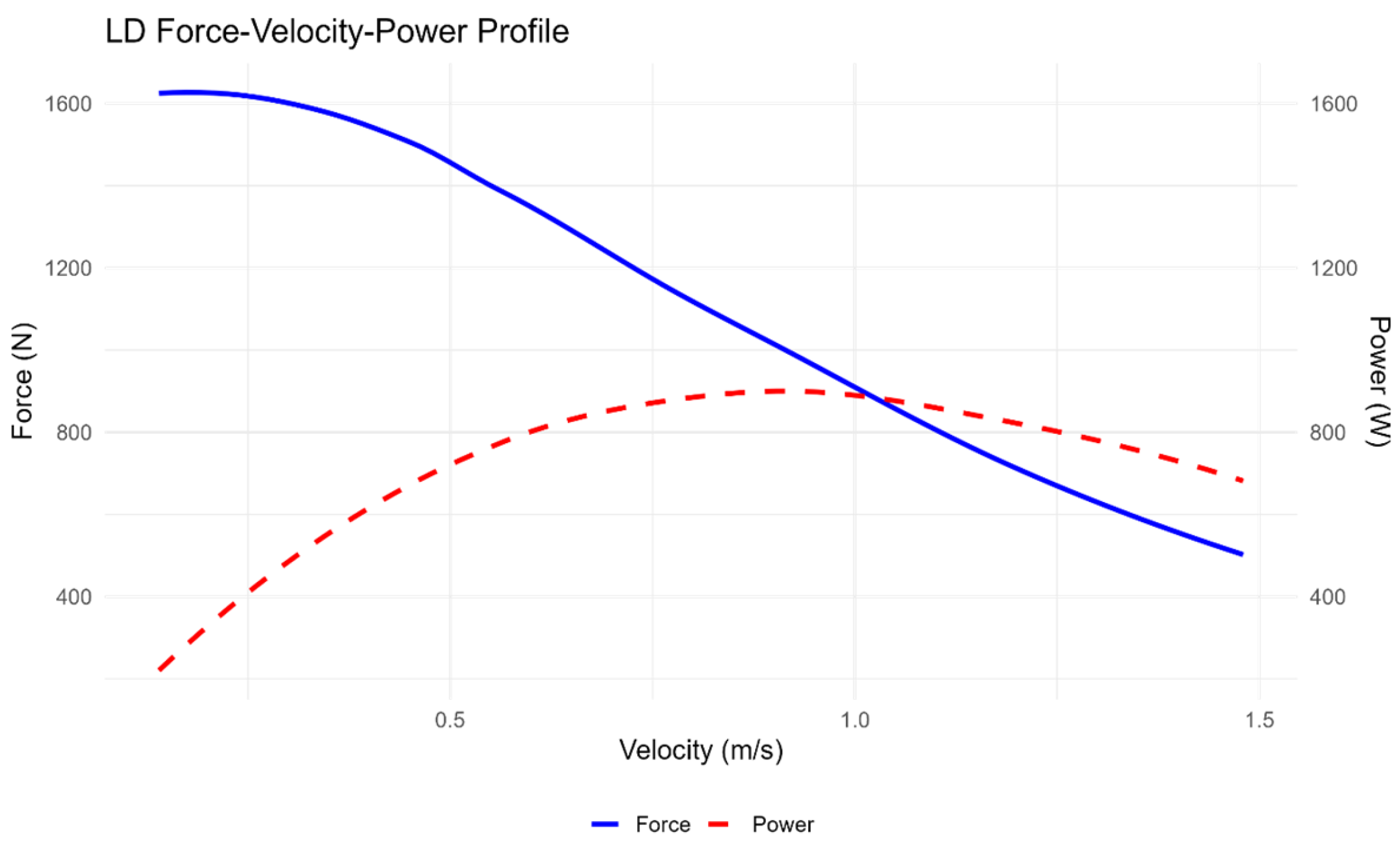

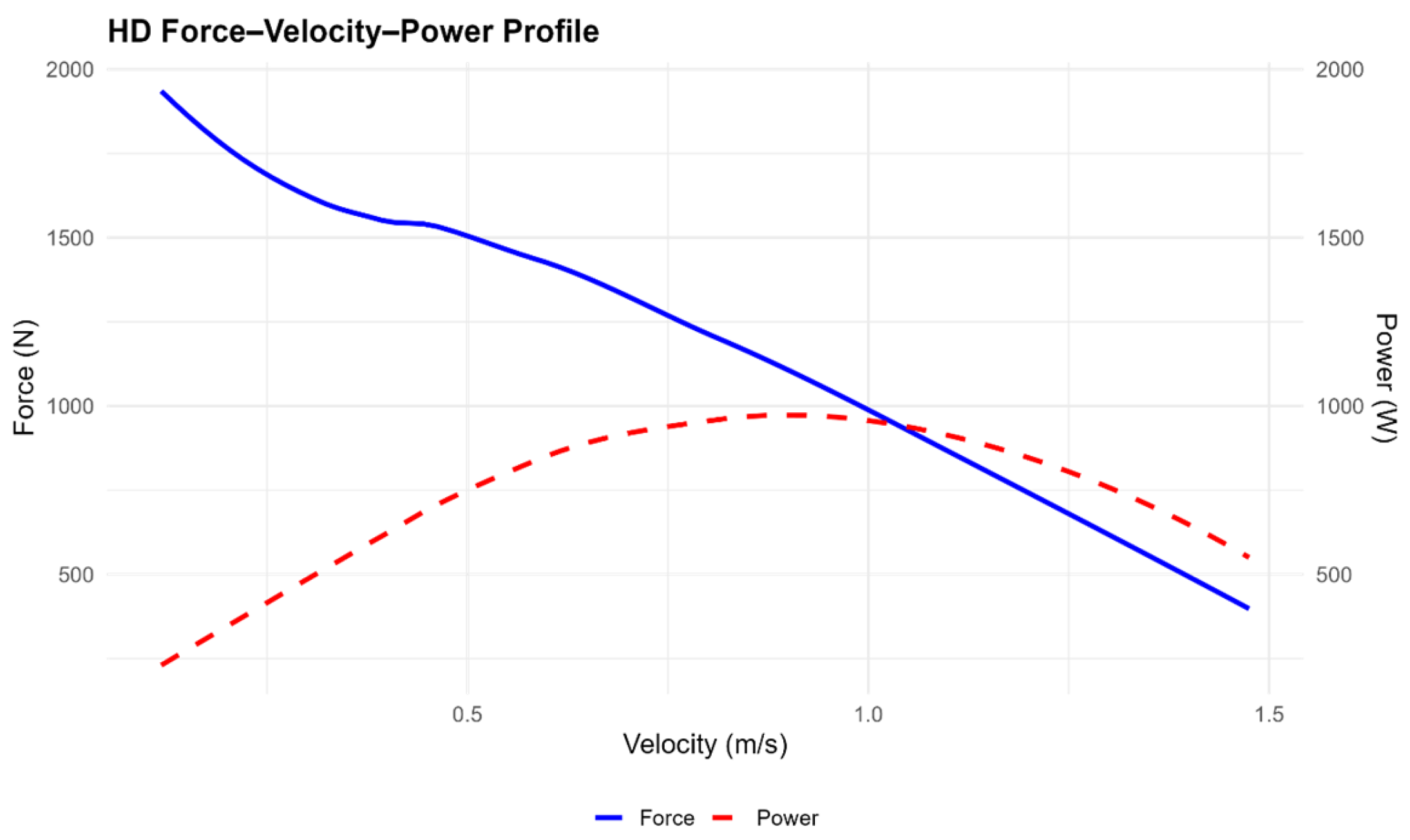

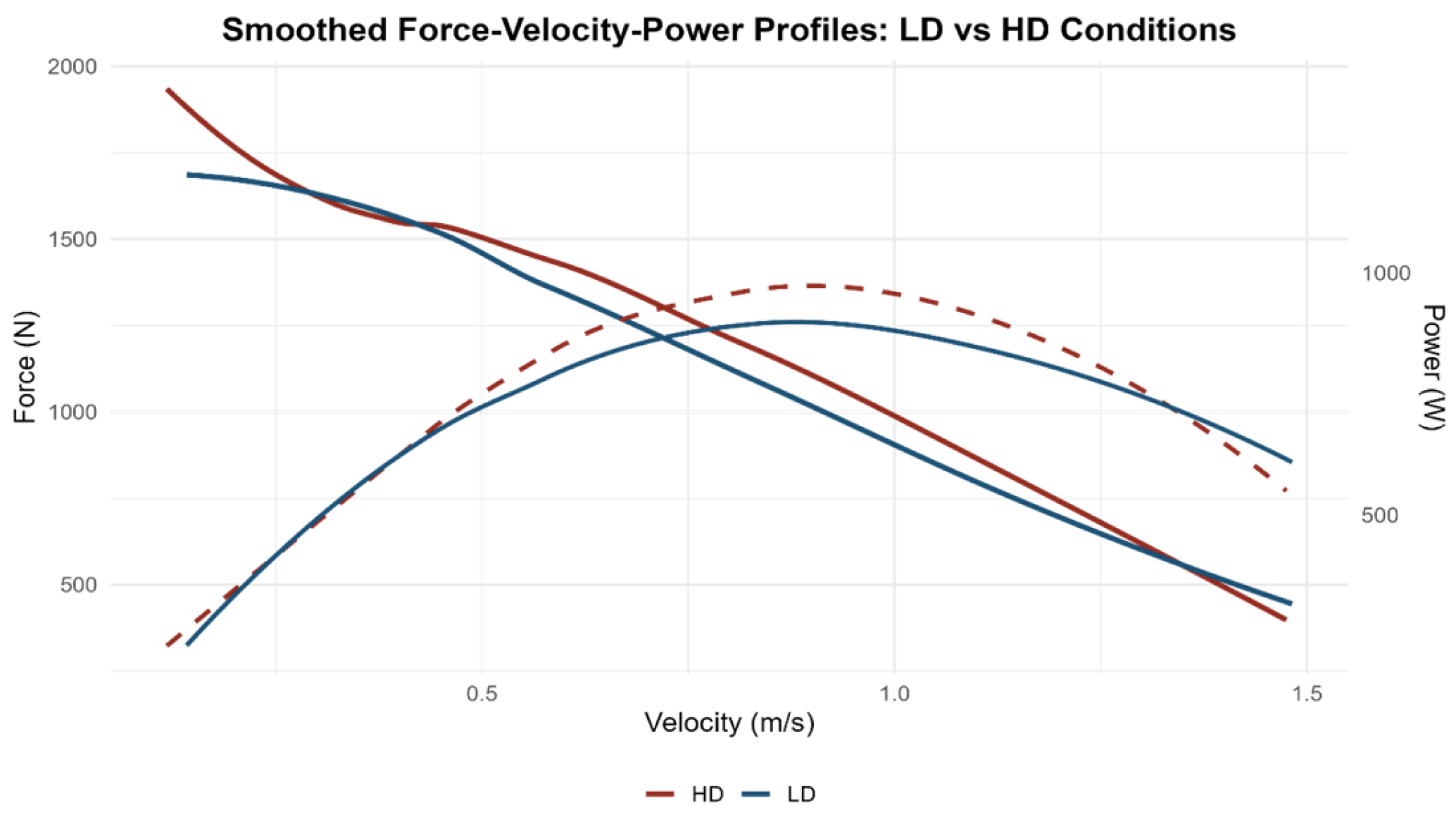

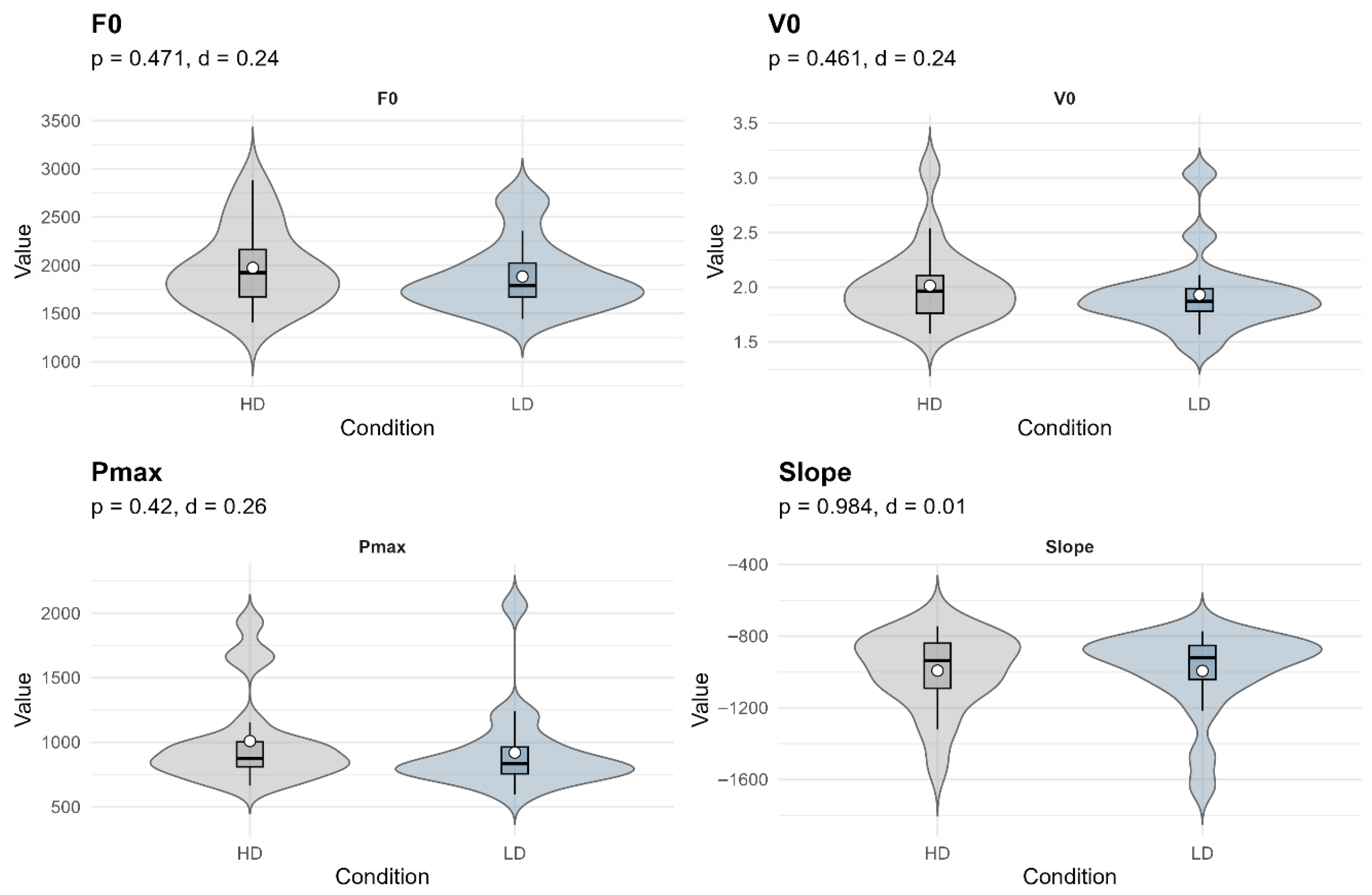

3. Results

| Descriptive Statistics by Condition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Condition | Summary Statistic | 95% CI | Reporting Format |

| F0 (N) | HD | 1974.04 ± 407.30 | 1790.90–2157.19 | Mean ± SD |

| V0 (m/s) | HD | 1.96 (1.76–2.11) | Median (IQR) | |

| Pmax (w) | HD | 873.93 (810.45–1003.32) | Median (IQR) | |

| Slope (N × s/m) | HD | −992.08 ± 206.95 | −1085.13–−899.03 | Mean ± SD |

| F0 (N) | LD | 1788.97 (1671.12–2023.80) | Median (IQR) | |

| V0 (m/s) | LD | 1.87 (1.78–1.99) | Median (IQR) | |

| Pmax (W) | LD | 834.69 (756.19–962.95) | Median (IQR) | |

| Slope (N × s/m) | LD | −920.05 (−1041.11–−851.57) | Median (IQR) | |

| Summary of Descriptive and Inferential Results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | LD (Mean ± SD) | HD (Mean ± SD) | HD-LD Difference | 95% CI | p-Value | Cohen’s d |

| F0 (N) | 1883.3 ± 359.1 | 1974 ± 407.3 | 90.780 | [−258.3, 76.73] | 0.270 | −0.369 |

| V0 (m/s) | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 2 ± 0.3 | 0.080 | [−0.256, 0.089] | 0.321 | −0.331 |

| Pmax (w) | 920.2 ± 320.1 | 1009.7 ± 354.8 | 89.540 | [−255.18, 76.11] | 0.271 | −0.368 |

| Slope (N × s/m) | −993.5 ± 228 | −992.1 ± 206.9 | 1.440 | [−76.24, 73.35] | 0.968 | −0.013 |

| Summary of Descriptive and Inferential Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Difference | 0.2 × SD (HD) | Interpretation |

| F0 (N) | 90.78 | 81.46 | Clinically significant |

| V0 (m/s) | 0.08 | 0.07 | Clinically significant |

| Pmax (w) | 89.54 | 70.96 | Clinically significant |

| Slope (N × s/m) | 1.44 | 41.39 | Trivial |

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Applicability and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cormie, P.; McGuigan, M.R.; Newton, R.U. Developing maximal neuromuscular power. Part 1—Biological basis of maximal power production. Sports Med. 2012, 41, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagianni, K.; Donti, O.; Katsikas, C.; Bogdanis, G.C. Effects of supplementary strength–power training on neuromuscular performance in young female athletes. Sports 2020, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagoulis, C.; Chatzinikolaou, A.; Avloniti, A.; Leontsini, D.; Deli, C.K.; Draganidis, D.; Stampoulis, T.; Oikonomou, T.; Papanikolaou, K.; Rafailakis, L.; et al. In-season integrative neuromuscular strength training improves performance of early-adolescent soccer athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askow, A.T.; Merrigan, J.J.; Neddo, J.M.; Oliver, J.M.; Stone, J.D.; Jagim, A.R.; Jones, M.T. Effect of strength on velocity and power during back squat exercise in resistance-trained men and women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferná Ortega, J.A.; Mendoza Romero, D.; Sarmento, H.; Prieto Mondragón, L.; Rodríguez Buitrago, J.A. Relationship between dynamic and isometric strength, power, speed, and average propulsive velocity of recreational athletes. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2022, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhea, M.R.; Kenn, J.G.; Dermody, B.M. Alterations in speed of squat movement and the use of accommodated resistance among college athletes training for power. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 2645–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistilli, E.E.; Mitchell, M.; Florence, L. Incorporating unilateral variations of weightlifting and powerlifting movements into the training program of college-level dancers to improve stability. Strength Cond. J. 2021, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapuppo, M.; Oberlin, D.J.; Burke, R.; Piñero, A.; Mohan, A.E.; Augustin, F.; Coleman, M.; Korakakis, P.; Nuckols, G.; Schoenfeld, B.J. Preparation for powerlifting competition: A case study. Int. J. Strength Cond. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machek, S.B.; Cardaci, T.D.; Wilburn, D.T.; Cholewinski, M.C.; Latt, S.L.; Harris, D.R.; Willoughby, D.S. Neoprene Knee Sleeves of Varying Tightness Augment Barbell Squat One Repetition Maximum Performance Without Improving Other Indices of Muscular Strength, Power, or Endurance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, S6–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.S.M.; Chung, L.M.Y.; Gao, Y.; Lee, J.C.W.; Chang, T.C.; Ma, A.W.W. The influence of weightlifting belts and wrist straps on deadlift kinematics, time to complete a deadlift and rating of perceived exertion in male recreational weightlifters: An observational study. Medicine 2022, 101, e28918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, G.R.; Marocolo, M. Editorial: Ergogenic aids: Physiological and performance responses. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 902024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rishiraj, N.; Taunton, J.E.; Lloyd-Smith, R.; Woollard, R.; Regan, W.; Clement, D.B. The potential role of prophylactic/functional knee bracing in preventing knee ligament injury. Sports Med. 2009, 39, 937–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Córdoba, J.P. Programación del Entrenamiento en Powerlifting. Editor Transverso. 2022. Available online: https://editorialtransverso.com/producto/programacion-del-entrenamiento-en-powerlif-ting/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Harman, E.F.P. The effects of knee wraps on weightlifting performance and injury. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1990, 12, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, R.D.; Machek, S.B.; Lorenz, K.A. Technical aspects and applications of the low-bar back squat. Strength Cond. J. 2020, 42, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, X.; Shen, X.; Chen, L.; Gong, H. Effectiveness of Kinesio tape in the treatment of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2024, 103, e38438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, L.; Simmonds, C.; Hatcher, J. The effect of a neoprene sleeve on knee joint position sense. Res. Sports Med. 2005, 13, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.; Mann, J.; Weston, G.; Poulsen, N.; Edmundson, C.J.; Bentley, I.; Stone, M. Acute effects of knee wraps/sleeve on kinetics, kinematics and muscle forces during the barbell back squat. Sport Sci. Health 2019, 16, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynart, F.R.; Mazuquin, B.; Costa, H.S.; Santos, T.R.T.; Brant, A.C.; Rodrigues, N.L.M.; Trede, R. Are 7 mm neoprene knee sleeves capable of modifying the knee kinematics and kinetics during box jump and front squat exercises in healthy CrossFit practitioners? An exploratory cross-sectional study. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2024, 40, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Nilson, F.; Gustavsson, J.; Ghai, I. Influence of compression garments on propriocep-tion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2024, 1536, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, J.P.; Carden, P.J.C.; Shorter, K.A. Wearing knee wraps affects mechanical output and performance characteristics of back squat exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 2844–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, R.-K.; Chae, W.-S.; Kang, N. Compression sportswear improves speed, endurance, and functional motor performances: A meta-analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez-Berlanga, A.; Babiloni-Lopez, C.; Ferri-Caruana, A.; Jiménez-Martínez, P.; García-Ramos, A.; Flandez, J.; Gene-Morales, J.; Colado, J.C. A new sports garment with elastomeric technology optimizes physiological, mechanical, and psychological acute responses to pushing upper-limb resistance exercises. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfield, D.L.; Stranieri, A.M.; Vincent, L.M.; Earp, J.E. Effect of a neoprene knee sleeve on performance and muscle activity in men and women during high-intensity, high-volume re-sistance training. J. Strength Cond. Res./Natl. Strength Condi-Tioning Assoc. 2021, 35, 3300–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leschot Gatica, J.; Guzman Muñoz, E.; Alarcón- Rivera, M.; Montoya Ramos, M.M.-R.; Leiva-Díaz, L. Comparison of high-density and low-density neoprene knee sleeves on back squat and CMJ performance. Retos 2025, 69, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Si, D.; Li, X.; Liang, Q.; Li, Q.; Huang, L.; Wei, S.; Liu, Y. Do compression garments enhance running performance? An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sport Health Sci. 2025, 14, 101028, Erratum in J. Sport Health Sci. 2025, 14, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbert, M.F.; Lindberg, K.; Bjørnsen, T.; Solberg, P.; Paulsen, G. The Force-Velocity Profile for Jumping: What It Is and What It Is Not. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2023, 55, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eythorsdottir, I.; Gløersen, Ø.; Rice, H.; Werkhausen, A.; Ettema, G.; Mentzoni, F.; Solberg, P.; Lindberg, K.; Paulsen, G. The Battle of the Equations: A Systematic Review of Jump Height Calculations Using Force Platforms. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 2771–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, T.; Okada, J. Influence of Strength Level on Performance Enhancement Using Resistance Priming. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spudić, D.; Smajla, D.; Šarabon, N. Force–velocity–power profiling in flywheel squats: Differences between sports and association with countermovement jump and change of direction performance. J. Sports Sci. 2024, 42, 1464–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Raya, A.; García-Mateo, P.; García-Ramos, A.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.A.; Soriano-Maldonado, A. Delineating the potential of the vertical and horizontal force-velocity profile for optimizing sport performance: A systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 40, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. 2024. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Sánchez-Medina, L.; Pallarés, J.G.; Pérez, C.E.; Morán-Navarro, R.; González-Badillo, J.J. Estimation of relative load from bar velocity in the full back squat exercise. Sports Med.-Int. Open 2017, 1, E80–E88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weakley, J.; Mann, B.; Banyard, H.; McLaren, S.; Scott, T.; Garcia-Ramos, A. Velocity-based train-ing: From theory to application. Strength Cond. J. 2021, 43, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samozino, P.; Hintzy, F. A simple method for measuring force, velocity and power output during a squat jump. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 2940–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Reyes, P.; Samozino, P.; Brughelli, M.; Morin, J.-B. Effectiveness of an individualized training based on force-velocity profiling during jumping. Front. Physiol. 2017, 7, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.W.; Batterham, A.M.; Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, T.A.; Breitschädel, F.; Seiler, S. Sprint mechanical variables in elite athletes: Are force–velocity profiles sport specific or individual? PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Statistics notes: Detecting skewness from summary information. BMJ 1996, 313, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T.A.; Altman, D.G. Basic statistical reporting for articles published in clinical medical journals: The Statistical Analyses and Methods in the Published Literature, or the SAMPL guidelines. In Science Editors’ Handbook, 2nd ed.; Maisonneuve, H., Polderman, A., Eds.; European Association of Science Editors: London, UK, 2013; pp. 175–180. Available online: https://www.ease.org.uk (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Weakley, J.; Broatch, J.; O’rIordan, S.; Morrison, M.; Maniar, N.; Halson, S.L. Putting the Squeeze on Compression Garments: Current Evidence and Recommendations for Future Research: A Systematic Scoping Review. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 1141–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leabeater, A.; Vickery-Howe, D.; Perrett, C.; James, L.; Middleton, K.; Driller, M. Evaluating the effect of sports compression tights on balance, sprinting, jumping and change of direction tasks. Sports Biomech. 2024, 24, 3269–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limmer, M.; de Marées, M.; Roth, R. Effects of Forearm Compression Sleeves on Muscle Hemodynamics and Muscular Strength and Endurance Parameters in Sports Climbing: A Randomized, Controlled Crossover Trial. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 888860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.H.; Lo, S.F.; Wu, H.C.; Chiu, M.C. Effects of compression garment on muscular efficacy, proprioception, and recovery after exercise-induced muscle fatigue onset for people who exercise regularly. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Su, H.; Du, L.; Li, G.; Lv, Y.; Liu, X.; Feng, L.; Yu, L. Effects of Compression Garments on Muscle Strength and Power Recovery Post-Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life 2025, 15, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Riordan, S.F.; McGregor, R.; Halson, S.L.; Bishop, D.J.; Broatch, J.R. Sports compression garments improve resting markers of venous return and muscle blood flow in male basketball players. J. Sport Health Sci. 2023, 12, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukic, I.; García-Ramos, A.; Tufano, J.J. Velocity-Based Resistance Training Monitoring: Influence of Lifting Straps, Reference Repetitions, and Variable Selection in Resistance-Trained Men. Sports Health 2023, 15, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noé, F.; Baige, K.; Paillard, T. Can Compression Garments Reduce Inter-Limb Balance Asymmetries? Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 835784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassier, R.; Espeit, L.; Ravel, A.; Beaudou, P.; Trama, R.; Edouard, P.; Thouze, A.; Féasson, L.; Hintzy, F.; Rossi, J.; et al. Beneficial effects of reduced soft tissue vibrations with compression garments on delayed neuromuscular impairments induced by an exhaustive downhill run. Front. Sports Act. 2025, 7, 1516617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leabeater, A.J.; James, L.P.; Driller, M.W. Tight Margins: Compression Garment Use during Exercise and Recovery-A Systematic Review. Textiles 2022, 2, 395–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeber, M.; Stafilidis, S.; Baca, A. The effect of stretch–shortening magnitude and muscle–tendon unit length on performance enhancement in a stretch–shortening cycle. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goecking, T.; Holzer, D.; Hahn, D.; Siebert, T.; Seiberl, W. Unlocking the benefit of active stretch: The eccentric muscle action, not the preload, maximizes muscle-tendon unit stretch-shortening cycle performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2024, 137, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, A.; Wallwork, S.B.; Witchalls, J.; Ball, N.; Waddington, G. The effect of a combined compression-tactile stimulating sock on postural stability. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1516182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, B.; Szabo, A. Placebo and Nocebo Effects on Sports and Exercise Performance: A Systematic Literature Review Update. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beato, M. Recommendations for the design of randomized controlled trials in strength and conditioning. Common design and data interpretation. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 981836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, D.N.; Barnett, A.G.; Caldwell, A.R.; White, N.M.; Stewart, I.B. The bias for statistical significance in sport and exercise medicine. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2023, 26, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.; Carson, R.; Tóth, K. Moving beyond P values in The Journal of Physiology: A primer on the value of effect sizes and confidence intervals. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 5131–5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; García-Ramos, A. Evaluating the Field 2-Point Method for the Relative Load-Velocity Relationship Monitoring in Free-Weight Back Squats. J. Hum. Kinet. 2024, 97, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicijevic, D.; Miras-Moreno, S.; Morenas-Aguilar, M.D.; García-Ramos, A. Does the Length of Inter-Set Rest Periods Impact the Volume of Bench Pull Repetitions Completed before Surpassing Various Cut-Off Velocities? J. Hum. Kinet. 2024, 95, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.; Cunha, R.; Gonçalves, C.; Dal Pupo, J.; Tufano, J. Force-velocity-power variables derived from isometric and dynamic testing: Metrics reliability and the relationship with jump performance. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, A.; Suarez, D.G.; Travis, S.K.; Slaton, J.A.; White, J.B.; Bazyler, C.D.; Stone, M.H. Intrasession and Intersession Reliability of Isometric Squat, Midthigh Pull, and Squat Jump in Resistance-Trained Individuals. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castilla, A.; Ruiz-Alias, S.A.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; García-Pinillos, F.; Marcos-Blanco, A. Reliability and Acute Changes in the Load-Velocity Profile During Countermovement Jump Exercise Following Different Velocity-Based Resistance Training Protocols in Recreational Runners. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2025, 25, e12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Ji, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, M.; He, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Sun, J.; Song, J.; Li, D. Comparing autoregulatory progressive resistance exercise and velocity-based resistance training on jump performance in college badminton athletes. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, D.; Hahn, D.; Schwirtz, A.; Siebert, T.; Seiberl, W. Decoupling of muscle-tendon unit and fascicle velocity contributes to the in vivo stretch-shortening cycle effect in the male human triceps surae muscle. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e70131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, P.; Thomas, C.; Dos’Santos, T.; Jones, P.A.; Suchomel, T.J.; McMahon, J.J. Comparison of Methods of Calculating Dynamic Strength Index. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chino, K.; Tokuoka, H.; Ito, Y. Development of Dynamic Strength Index Based on Free-Weight Exercises for Collegiate Male Sprinters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2025, 39, e639–e646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leschot-Gatica, J.; Romero-Vera, L.; Ñancupil-Andrade, A.; Hernández-Mosqueira, C.; Molina-Márquez, I.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Montalva-Valenzuela, F.; Guzmán-Muñoz, E. Effects of Knee Sleeve Density on Theoretical Neuromuscular Capacities Derived from the Force–Velocity–Power Profile in the Back Squat. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2026, 11, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010047

Leschot-Gatica J, Romero-Vera L, Ñancupil-Andrade A, Hernández-Mosqueira C, Molina-Márquez I, Yáñez-Sepúlveda R, Montalva-Valenzuela F, Guzmán-Muñoz E. Effects of Knee Sleeve Density on Theoretical Neuromuscular Capacities Derived from the Force–Velocity–Power Profile in the Back Squat. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2026; 11(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeschot-Gatica, Jorge, Luis Romero-Vera, Alberto Ñancupil-Andrade, Claudio Hernández-Mosqueira, Iván Molina-Márquez, Rodrigo Yáñez-Sepúlveda, Felipe Montalva-Valenzuela, and Eduardo Guzmán-Muñoz. 2026. "Effects of Knee Sleeve Density on Theoretical Neuromuscular Capacities Derived from the Force–Velocity–Power Profile in the Back Squat" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 11, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010047

APA StyleLeschot-Gatica, J., Romero-Vera, L., Ñancupil-Andrade, A., Hernández-Mosqueira, C., Molina-Márquez, I., Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R., Montalva-Valenzuela, F., & Guzmán-Muñoz, E. (2026). Effects of Knee Sleeve Density on Theoretical Neuromuscular Capacities Derived from the Force–Velocity–Power Profile in the Back Squat. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 11(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010047