Assessing Reliability in Flywheel Squat Performance: The Role of Sex and Inertial Load

Abstract

1. Introduction

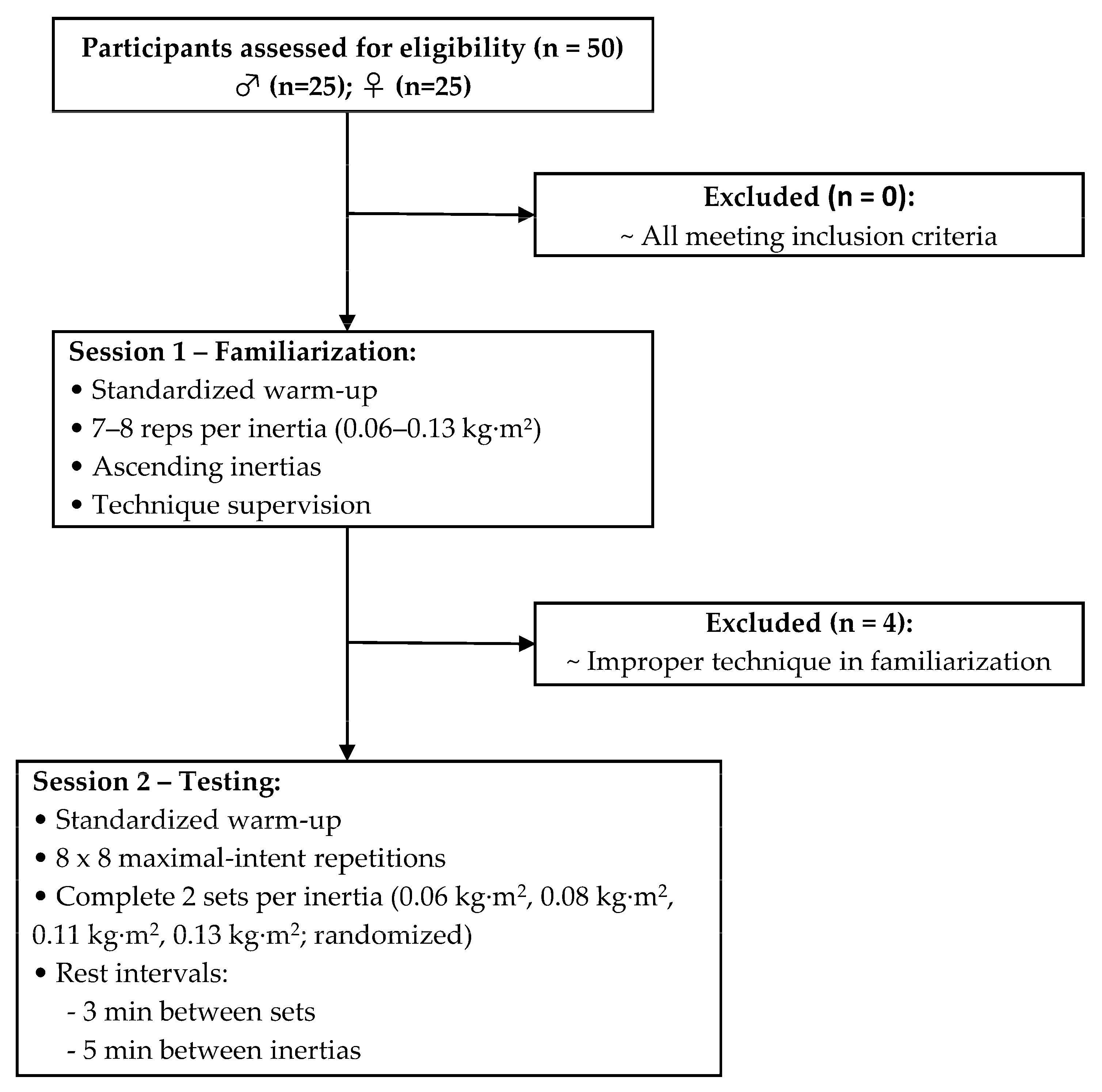

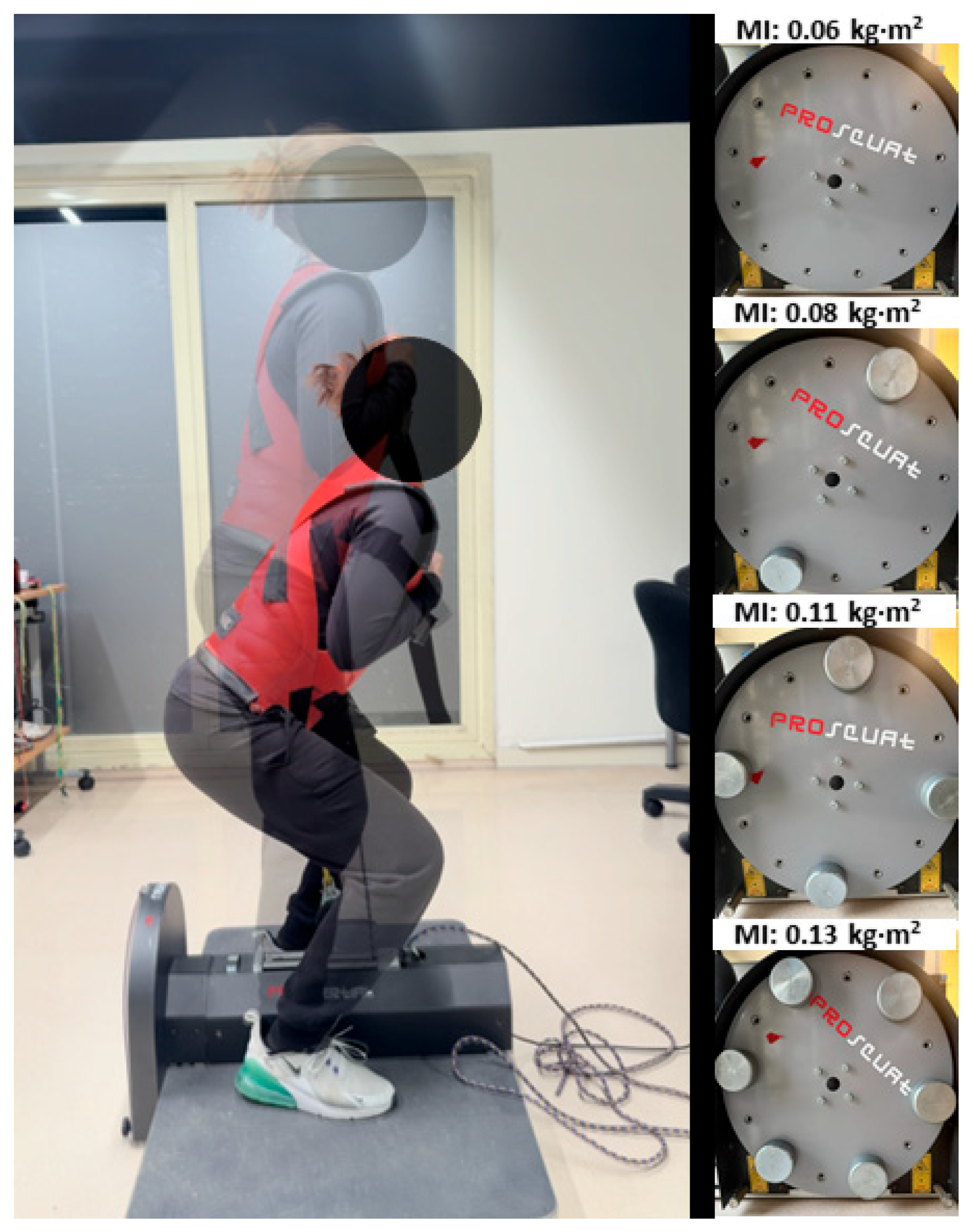

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Approach

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Processing

2.5. Statistical Analysis

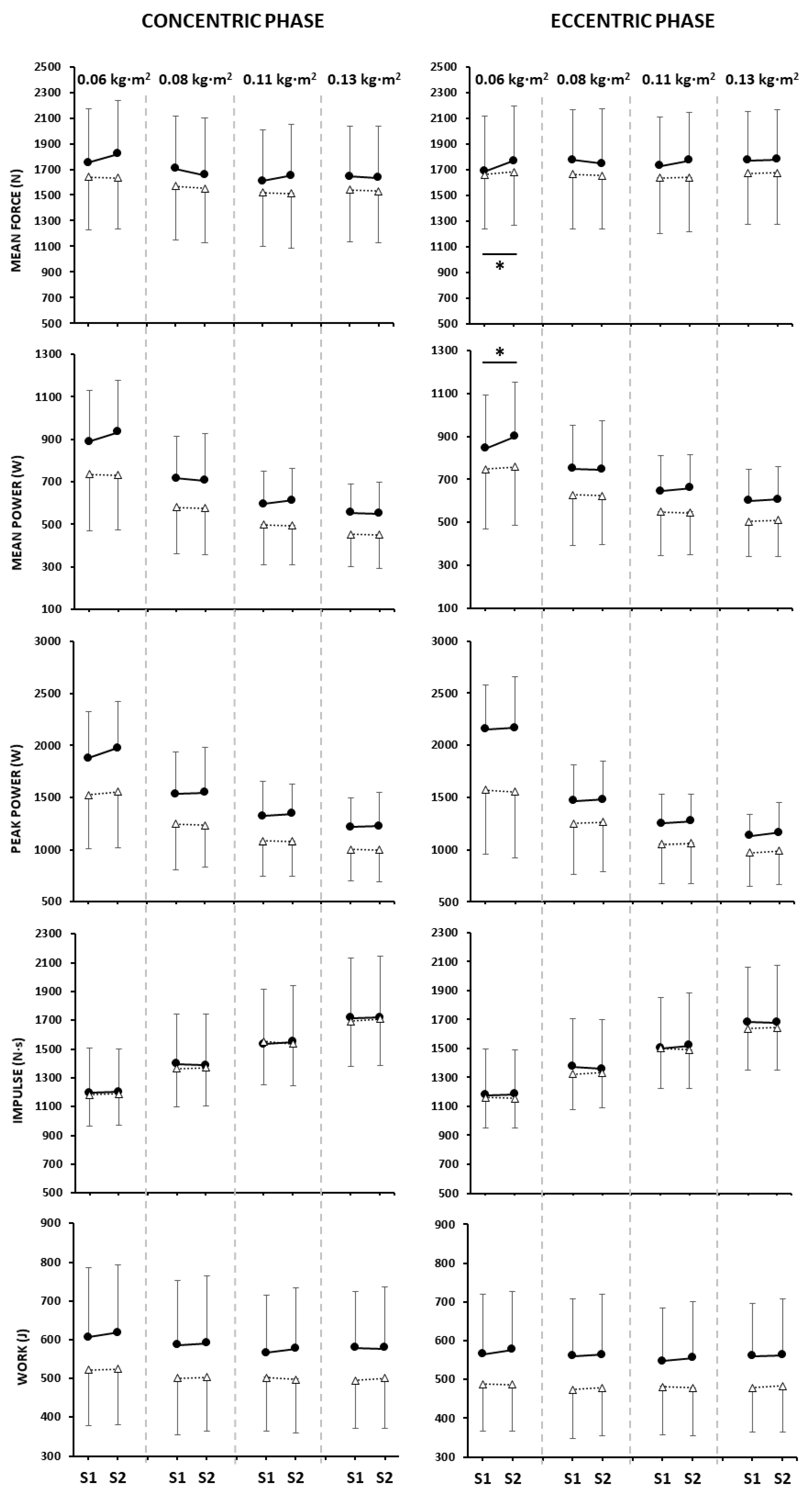

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Sex on Reliability

4.2. Influence of Inertial Settings

5. Practical Applications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FD | Flywheel device |

| CON | Concentric |

| ECC | Eccentric |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| SEM | Standard error of the measurement |

| SWC | Smallest worthwhile change |

| MDC | Minimal detectable change |

| TE | Typical error |

| MI | Moment of inertia |

| DIFset | Difference between sets |

| PAPE | Post-activation potentiation enhancement |

References

- Myer, G.D.; Kushner, A.M.; Brent, J.L.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Hugentobler, J.; Lloyd, R.S.; Vermeil, A.; Chu, D.A.; Harbin, J.; McGill, S.M. The back squat: A proposed assessment of functional deficits and technical factors that limit performance. Strength. Cond. J. 2014, 36, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelly, M.S.; Fathloun, M.; Cherif, N.; Ben Amar, M.; Tabka, Z.; Van Praagh, E. Effects of a back squat training program on leg power, jump, and sprint performances in junior soccer players. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 2241–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, K.; Yata, H.; Kanehisa, H.; Fukunaga, T. Effects of isometric squat training on the tendon stiffness and jump performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 96, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkner, B.A.; Bring, D.K. Muscle Activation During Gravity-Independent Resistance Exercise Compared to Common Exercises. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 2019, 90, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.E.; Tesch, A. A gravity-independent ergometer to be used for resistance training in space. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 1994, 65, 752–756. [Google Scholar]

- de Hoyo, M.; Pozzo, M.; Sanudo, B.; Carrasco, L.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Dominguez-Cobo, S.; Moran-Camacho, E. Effects of a 10-week in-season eccentric-overload training program on muscle-injury prevention and performance in junior elite soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puustinen, J.; Venojarvi, M.; Haverinen, M.; Lundberg, T.R. Effects of Flywheel vs. Traditional Resistance Training on Neuromuscular Performance of Elite Ice Hockey Players. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illera-Dominguez, V.; Nuell, S.; Carmona, G.; Padulles, J.M.; Padulles, X.; Lloret, M.; Cusso, R.; Alomar, X.; Cadefau, J.A. Early Functional and Morphological Muscle Adaptations During Short-Term Inertial-Squat Training. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto-Izquierdo, S.; Garcia-Lopez, D.; Fernandez-Gonzalo, R.; Moreira, O.C.; Gonzalez-Gallego, J.; de Paz, J.A. Skeletal muscle functional and structural adaptations after eccentric overload flywheel resistance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, J.; Pearson, S.; Ross, A.; McGuigan, M. Eccentric Exercise: Physiological Characteristics and Acute Responses. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hody, S.; Croisier, J.L.; Bury, T.; Rogister, B.; Leprince, P. Eccentric Muscle Contractions: Risks and Benefits. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrbrand, L.; Pozzo, M.; Tesch, P.A. Flywheel resistance training calls for greater eccentric muscle activation than weight training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 110, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seynnes, O.R.; de Boer, M.; Narici, M.V. Early skeletal muscle hypertrophy and architectural changes in response to high-intensity resistance training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007, 102, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, N.M.; Snijders, T.; McKay, B.R.; Parise, G.; Verdijk, L.B.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Gibala, M.J.; Van Loon, L.J. Eccentric exercise increases satellite cell content in type II muscle fibers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2013, 45, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toigo, M.; Boutellier, U. New fundamental resistance exercise determinants of molecular and cellular muscle adaptations. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 97, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McErlain-Naylor, S.A.; Beato, M. Concentric and eccentric inertia-velocity and inertia-power relationships in the flywheel squat. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras-Sanchiz, F.; Sabido, R.; Raya-Gonzalez, J.; Madruga-Parera, M.; Romero-Rodriguez, D.; Beato, M.; de Hoyo, M.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Hernandez-Davo, J.L. Effects of Different Inertial Load Settings on Power Output using a Flywheel Leg Curl Exercise and its Inter-Session Reliability. J. Hum. Kinet. 2020, 74, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabido, R.; Hernandez-Davo, J.L.; Pereyra-Gerber, G.T. Influence of Different Inertial Loads on Basic Training Variables During the Flywheel Squat Exercise. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Aranda, L.M.; Fernandez-Gonzalo, R. Effects of Inertial Setting on Power, Force, Work, and Eccentric Overload During Flywheel Resistance Exercise in Women and Men. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-López, A.; Nakamura, F.Y. Measuring and Testing with Flywheel Resistance Training Devices. In Resistance Training Methods: From Theory to Practice; Muñoz-López, A., Taiar, R., Sañudo, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bollinger, L.M.; Brantley, J.T.; Tarlton, J.K.; Baker, P.A.; Seay, R.F.; Abel, M.G. Construct Validity, Test-Retest Reliability, and Repeatability of Performance Variables Using a Flywheel Resistance Training Device. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 3149–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tous-Fajardo, J.; Maldonado, R.A.; Quintana, J.M.; Pozzo, M.; Tesch, P.A. The flywheel leg-curl machine: Offering eccentric overload for hamstring development. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2006, 1, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, B.L.; Lininger, M.R. Statistical Primer for Athletic Trainers: The Essentials of Understanding Measures of Reliability and Minimal Important Change. J. Athl. Train. 2018, 53, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med. 2000, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, G.; Nevill, A.M. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998, 26, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illera-Dominguez, V.; Fernandez-Valdes, B.; Gisbert-Orozco, J.; Ramirez-Lopez, C.; Nuell, S.; Gonzalez, J.; Weakley, J. Validity of a low-cost friction encoder for measuring velocity, force and power in flywheel exercise devices. Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto-Izquierdo, S.; Nosaka, K.; Alarcon-Gomez, J.; Martin-Rivera, F. Validity and Reliability of Inertial Measurement System for Linear Movement Velocity in Flywheel Squat Exercise. Sensors 2023, 23, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illera-Domínguez, V.; Font-Aragonés, X.; Toro-Román, V.; Díaz-Alejandre, S.; Pérez-Chirinos, C.; Albesa-Albiol, L.; González-Millán, S.; Fernández-Valdés, B. Validity of Force and Power Measures from an Integrated Rotary Encoder in a HandyGym Portable Flywheel Exercise Device. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-San Agustin, R.; Sanchez-Barbadora, M.; Garcia-Vidal, J.A. Validity of an inertial system for measuring velocity, force, and power during hamstring exercises performed on a flywheel resistance training device. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weakley, J.; Fernandez-Valdes, B.; Thomas, L.; Ramirez-Lopez, C.; Jones, B. Criterion Validity of Force and Power Outputs for a Commonly Used Flywheel Resistance Training Device and Bluetooth App. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 1180–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spudić, D.; Cvitkovič, R.; Šarabon, N. Assessment and Evaluation of Force–Velocity Variables in Flywheel Squats: Validity and Reliability of Force Plates, a Linear Encoder Sensor, and a Rotary Encoder Sensor. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spudić, D.; Smajla, D.; Šarabon, N. Validity and reliability of force-velocity outcome parameters in flywheel squats. J. Biomech. 2020, 107, 109824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Keijzer, K.L.; Gonzalez, J.R.; Beato, M. The effect of flywheel training on strength and physical capacities in sporting and healthy populations: An umbrella review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Browne, D.; Moody, J.A.; Byrne, P.J. Intra- and Inter-Day Reliability of Inertial Loads with Cluster Sets When Performed during a Quarter Squat on a Flywheel Device. Sports 2023, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beato, M.; Fleming, A.; Coates, A.; Dello Iacono, A. Validity and reliability of a flywheel squat test in sport. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, C.; Beato, M.; McErlain-Naylor, S.A.; Iacono, A.D.; de Keijzer, K.L. Concentric Phase Assistance Enhances Eccentric Peak Power During Flywheel Squats: Intersession Reliability and the Linear Relationship Between Concentric and Eccentric Phases. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2023, 18, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, K.M.; Wagle, J.P.; Sato, K.; Taber, C.B.; Yoshida, N.; Bingham, G.E.; Stone, M.H. Characterising overload in inertial flywheel devices for use in exercise training. Sports Biomech. 2019, 18, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Keijzer, K.L.; McErlain-Naylor, S.A.; Beato, M. The Effect of Flywheel Inertia on Peak Power and Its Inter-session Reliability During Two Unilateral Hamstring Exercises: Leg Curl and Hip Extension. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 898649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Rivera, F.; Beato, M.; Alepuz-Moner, V.; Maroto-Izquierdo, S. Use of concentric linear velocity to monitor flywheel exercise load. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 961572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.K. Sex differences in human fatigability: Mechanisms and insight to physiological responses. Acta Physiol. 2014, 210, 768–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salse-Batan, J.; Torrado, P.; Marina, M. Are There Differences Between Sexes in Performance-Related Variables During a Maximal Intermittent Flywheel Test? Sports Health A Multidiscip. Approach 2025, 17, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Tillaar, R.; Bao Fredriksen, A.; Hegdahl Gundersen, A.; Nygaard Falch, H. Sex differences in intra-set kinematics and electromyography during different maximum repetition sets in the barbell back squat? PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegdahl Gundersen, A.; Nygaard Falch, H.; Bao Fredriksen, A.; Tillaar, R.V.D. The Effect of Sex and Different Repetition Maximums on Kinematics and Surface Electromyography in the Last Repetition of the Barbell Back Squat. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spudić, D.; Kambič, T.; Cvitkovič, R.; Primož, P. Reproducibility and criterion validity of data derived from a flywheel resistance exercise system. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 28, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, W.N. A Web-based Sample Size Calculator for Reliability Studies. J. Educ. Med. J. 2018, 10, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163, Erratum in J. Chiropr. Med. 2017, 16, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormack, S.J.; Newton, R.U.; McGuigan, M.R.; Doyle, T.L. Reliability of measures obtained during single and repeated countermovement jumps. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2008, 3, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber, S.C.; Porter, M.M. Reliability of ankle isometric, isotonic, and isokinetic strength and power testing in older women. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. How to interpret changes in an athletic performance test. Sportscience 2004, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sabido, R.; Hernandez-Davo, J.L.; Botella, J.; Navarro, A.; Tous-Fajardo, J. Effects of adding a weekly eccentric-overload training session on strength and athletic performance in team-handball players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 17, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Marcora, S.M. Test validation in sport physiology: Lessons learned from clinimetrics. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2009, 4, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beato, M.; Bigby, A.E.J.; De Keijzer, K.L.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Coratella, G.; McErlain-Naylor, S.A. Post-activation potentiation effect of eccentric overload and traditional weightlifting exercise on jumping and sprinting performance in male athletes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yu, Y.; Niu, Y.; Ren, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M. Post-activation performance enhancement of flywheel and traditional squats on vertical jump under individualized recovery time. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1443899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Fernandez, F.; Lopez-Contreras, G.; Arellano, R. Effect on swimming start performance of two types of activation protocols: Lunge and YoYo squat. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzzo, J.L. Narrative Review of Sex Differences in Muscle Strength, Endurance, Activation, Size, Fiber Type, and Strength Training Participation Rates, Preferences, Motivations, Injuries, and Neuromuscular Adaptations. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 494–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L.B.; Haff, G.G. Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation of Jump, Sprint, Throw, and Upper-Body Ballistic Performances: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, T.; Sale, D.G.; MacDougall, J.D.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Postactivation potentiation, fiber type, and twitch contraction time in human knee extensor muscles. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 88, 2131–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, S.K.; Angadi, S.S.; Bhargava, A.; Harper, J.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Levine, B.D.; Moreau, K.L.; Nokoff, N.J.; Stachenfeld, N.S.; Bermon, S. The Biological Basis of Sex Differences in Athletic Performance: Consensus Statement for the American College of Sports Medicine. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2023, 55, 2328–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujika, I.; Taipale, R.S. Sport Science on Women, Women in Sport Science. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 1013–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, S.K.; Senefeld, J.W. Sex differences in human performance. J. Physiol. 2024, 602, 4129–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worcester, K.S.; Baker, P.A.; Bollinger, L.M. Effects of Inertial Load on Sagittal Plane Kinematics of the Lower Extremity During Flywheel-Based Squats. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, P.; Jones, P.A.; Udall, R. The effect of load and sex on kinematic and kinetic variables during the mid-thigh clean pull. Sports Biomech. 2015, 14, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, L.Z.; Salem, G.J. Comparison of joint kinetics during free weight and flywheel resistance exercise. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | Age (Years) | Mass (kg) | Height (cm) | Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | Training (Day/Week) | Strength Training Experience (Years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 21 | 24.9 (5.1) | 76.6 (9.9) | 180.5 (5.3) | 23.4 (2.7) | 4.3 (1.3) | 9.9 (6.7) |

| Females | 25 | 23.6 (6) | 62.7 (7.7) | 165.1 (4) | 22.8 (2.8) | 4.4 (1.2) | 10.1 (4.1) |

| MI | SEX | DIFset | ICC (95% CI) | CV% | SWC | TE | MDC | MDC% | TE vs. SWC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEAN FORCE | |||||||||

| 0.06 | F | 60 ± 51 | 0.991 (0.978–0.996) | 2% | 97.0 | 46.0 | 127.6 | 8 | good |

| 0.08 | F | 55 ± 61 | 0.991 (0.979–0.996) | 3% | 95.9 | 45.5 | 126.1 | 8 | good |

| 0.11 | F | 52 ± 42 | 0.994 (0.985–0.997) | 2% | 93.6 | 36.3 | 100.5 | 7 | good |

| 0.13 | F | 53 ± 41 | 0.993 (0.984–0.997) | 3% | 91.4 | 38.2 | 106.0 | 7 | good |

| 0.06 | M | 120 ± 118 | 0.964 (0.910–0.985) | 5% | 106.1 | 100.6 | 278.9 | 16 | good |

| 0.08 | M | 111 ± 127 | 0.962 (0.907–0.985) | 5% | 113.4 | 110.5 | 306.3 | 19 | good |

| 0.11 | M | 102 ± 72 | 0.977 (0.944–0.991) | 4% | 104.6 | 79.4 | 220.0 | 14 | good |

| 0.13 | M | 58 ± 45 | 0.991 (0.979–0.996) | 3% | 109.7 | 52.1 | 144.3 | 9 | good |

| MEAN POWER | |||||||||

| 0.06 | F | 47 ± 45 | 0.984 (0.964–0.993) | 4% | 65.8 | 41.6 | 115.4 | 16 | good |

| 0.08 | F | 29 ± 31 | 0.990 (0.978–0.996) | 4% | 62.4 | 31.2 | 86.5 | 15 | good |

| 0.11 | F | 25 ± 22 | 0.992 (0.981–0.996) | 4% | 51.9 | 23.2 | 64.4 | 13 | good |

| 0.13 | F | 25 ± 18 | 0.990 (0.977–0.996) | 4% | 47.7 | 23.8 | 66.1 | 15 | good |

| 0.06 | M | 78 ± 64 | 0.964 (0.910–0.985) | 7% | 68.5 | 65.0 | 180.1 | 22 | good |

| 0.08 | M | 63 ± 53 | 0.959 (0.898–0.983) | 7% | 71.8 | 72.7 | 201.6 | 32 | marginal |

| 0.11 | M | 54 ± 48 | 0.943 (0.858–0.977) | 6% | 55.5 | 66.2 | 183.6 | 34 | marginal |

| 0.13 | M | 31 ± 23 | 0.981 (0.954–0.992) | 4% | 55.8 | 38.4 | 106.5 | 21 | good |

| PEAK POWER | |||||||||

| 0.06 | F | 104 ± 88 | 0.983 (0.963–0.993) | 5% | 165.6 | 177.8 | 299.2 | 19 | marginal |

| 0.08 | F | 93 ± 84 | 0.977 (0.948–0.990) | 5% | 117.3 | 134.4 | 246.5 | 20 | marginal |

| 0.11 | F | 58 ± 46 | 0.988 (0.972–0.995) | 4% | 114.7 | 137.9 | 174.2 | 16 | marginal |

| 0.13 | F | 71 ± 51 | 0.978 (0.951–0.990) | 5% | 86.0 | 74.1 | 172.8 | 17 | good |

| 0.06 | M | 161 ± 135 | 0.954 (0.886–0.981) | 6% | 165.8 | 107.9 | 492.8 | 29 | good |

| 0.08 | M | 123 ± 95 | 0.964 (0.910–0.985) | 6% | 141.7 | 88.9 | 372.5 | 27 | good |

| 0.11 | M | 125 ± 111 | 0.920 (0.804–0.968) | 7% | 97.5 | 62.8 | 382.3 | 32 | good |

| 0.13 | M | 73 ± 47 | 0.979 (0.948–0.991) | 5% | 99.9 | 62.3 | 205.4 | 19 | good |

| IMPULSE | |||||||||

| 0.06 | F | 35 ± 39 | 0.988 (0.973–0.995) | 2% | 50.2 | 27.5 | 76.2 | 6 | good |

| 0.08 | F | 33 ± 28 | 0.994 (0.986–0.997) | 2% | 53.2 | 20.6 | 57.2 | 4 | good |

| 0.11 | F | 34 ± 25 | 0.995 (0.989–0.998) | 2% | 51.9 | 18.4 | 50.9 | 3 | good |

| 0.13 | F | 51 ± 30 | 0.993 (0.983–0.997) | 2% | 56.6 | 23.7 | 65.6 | 4 | good |

| 0.06 | M | 33 ± 22 | 0.994 (0.986–0.998) | 2% | 61.2 | 23.7 | 65.7 | 6 | good |

| 0.08 | M | 59 ± 87 | 0.976 (0.941–0.990) | 3% | 63.1 | 48.9 | 135.5 | 10 | good |

| 0.11 | M | 38 ± 52 | 0.994 (0.984–0.997) | 2% | 63.5 | 24.6 | 68.2 | 4 | good |

| 0.13 | M | 42 ± 31 | 0.994 (0.986–0.998) | 2% | 69.6 | 27.0 | 74.8 | 4 | good |

| WORK | |||||||||

| 0.06 | F | 28 ± 32 | 0.977 (0.948–0.990) | 4% | 30.3 | 23.0 | 63.8 | 12 | good |

| 0.08 | F | 22 ± 15 | 0.991 (0.980–0.996) | 3% | 35.7 | 17.0 | 47.0 | 9 | good |

| 0.11 | F | 19 ± 12 | 0.993 (0.984–0.997) | 3% | 27.6 | 11.6 | 32.0 | 6 | good |

| 0.13 | F | 26 ± 18 | 0.984 (0.964–0.993) | 4% | 31.0 | 19.6 | 54.3 | 11 | good |

| 0.06 | M | 31 ± 19 | 0.990 (0.976–0.996) | 4% | 34.4 | 17.2 | 47.7 | 8 | good |

| 0.08 | M | 42 ± 38 | 0.971 (0.929–0.988) | 5% | 41.6 | 35.4 | 98.2 | 18 | good |

| 0.11 | M | 28 ± 32 | 0.981 (0.952–0.992) | 4% | 31.3 | 21.6 | 59.7 | 11 | good |

| 0.13 | M | 25 ± 20 | 0.988 (0.971–0.995) | 3% | 36.3 | 19.9 | 55.1 | 10 | good |

| MI | SEX | DIF | ICC (95% CI) | CV% | SWC | TE | MDC | MDC% | TE vs. SWC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEAN FORCE | |||||||||

| 0.06 | F | 55 ± 45 | 0.993 (0.985–0.997) | 2% | 84.2 | 35.2 | 97.7 | 6 | good |

| 0.08 | F | 64 ± 59 | 0.989 (0.975–0.995) | 3% | 81.9 | 42.9 | 119.0 | 7 | good |

| 0.11 | F | 63 ± 55 | 0.990 (0.978–0.996) | 3% | 83.8 | 41.9 | 116.2 | 7 | good |

| 0.13 | F | 49 ± 42 | 0.993 (0.985–0.997) | 2% | 84.2 | 35.2 | 97.7 | 6 | good |

| 0.06 | M | 92 ± 82 | 0.988 (0.971–0.995) | 4% | 85.4 | 46.8 | 129.6 | 8 | good |

| 0.08 | M | 102 ± 113 | 0.964 (0.912–0.986) | 4% | 83.4 | 79.2 | 219.4 | 13 | good |

| 0.11 | M | 96 ± 61 | 0.980 (0.950–0.992) | 4% | 81.6 | 57.7 | 160.0 | 9 | good |

| 0.13 | M | 62 ± 47 | 0.989 (0.974–0.996) | 3% | 85.4 | 44.8 | 124.1 | 7 | good |

| MEAN POWER | |||||||||

| 0.06 | F | 47 ± 46 | 0.985 (0.967–0.994) | 4% | 55.1 | 33.8 | 93.6 | 12 | good |

| 0.08 | F | 36 ± 31 | 0.989 (0.976–0.995) | 4% | 52.8 | 27.7 | 76.8 | 12 | good |

| 0.11 | F | 28 ± 25 | 0.991 (0.980–0.996) | 4% | 46.3 | 22.0 | 60.9 | 11 | good |

| 0.13 | F | 27 ± 21 | 0.990 (0.976–0.995) | 4% | 43.8 | 21.9 | 60.7 | 12 | good |

| 0.06 | M | 62 ± 45 | 0.988 (0.972–0.995) | 6% | 50.6 | 27.7 | 76.7 | 9 | good |

| 0.08 | M | 59 ± 52 | 0.964 (0.910–0.985) | 6% | 48.6 | 46.1 | 127.8 | 19 | good |

| 0.11 | M | 54 ± 44 | 0.952 (0.881–0.980) | 6% | 42.9 | 47.0 | 130.3 | 22 | marginal |

| 0.13 | M | 31 ± 26 | 0.981 (0.954–0.992) | 4% | 41.8 | 28.8 | 79.9 | 14 | good |

| PEAK POWER | |||||||||

| 0.06 | F | 196 ± 200 | 0.946 (0.877–0.976) | 8% | 124.4 | 144.6 | 400.7 | 26 | marginal |

| 0.08 | F | 103 ± 103 | 0.976 (0.946–0.989) | 6% | 105.5 | 81.7 | 226.5 | 18 | good |

| 0.11 | F | 90 ± 68 | 0.977 (0.949–0.990) | 6% | 96.0 | 72.8 | 201.8 | 19 | good |

| 0.13 | F | 65 ± 45 | 0.985 (0.966–0.993) | 5% | 84.3 | 51.6 | 143.1 | 15 | good |

| 0.06 | M | 253 ± 269 | 0.803 (0.515–0.920) | 9% | 91.9 | 203.9 | 565.2 | 26 | marginal |

| 0.08 | M | 145 ± 101 | 0.933 (0.835–0.973) | 7% | 89.7 | 116.1 | 321.8 | 24 | marginal |

| 0.11 | M | 134 ± 138 | 0.855 (0.642–0.941) | 7% | 71.4 | 135.9 | 376.8 | 33 | marginal |

| 0.13 | M | 95 ± 76 | 0.940 (0.853–0.976) | 6% | 84.0 | 102.9 | 285.2 | 27 | marginal |

| IMPULSE | |||||||||

| 0.06 | F | 34 ± 32 | 0.989 (0.975–0.995) | 2% | 41.5 | 21.8 | 60.4 | 5 | good |

| 0.08 | F | 28 ± 21 | 0.995 (0.989–0.998) | 2% | 43.9 | 15.5 | 43.1 | 3 | good |

| 0.11 | F | 34 ± 19 | 0.995 (0.989–0.998) | 2% | 48.6 | 17.2 | 47.7 | 3 | good |

| 0.13 | F | 46 ± 26 | 0.992 (0.982–0.996) | 2% | 53.2 | 23.8 | 65.9 | 4 | good |

| 0.06 | M | 32 ± 23 | 0.994 (0.986–0.998) | 2% | 62.6 | 24.2 | 67.2 | 6 | good |

| 0.08 | M | 64 ± 107 | 0.965 (0.914–0.986) | 3% | 60.8 | 56.9 | 157.6 | 12 | good |

| 0.11 | M | 37 ± 43 | 0.994 (0.984–0.997) | 2% | 67.2 | 26.0 | 72.2 | 5 | good |

| 0.13 | M | 37 ± 28 | 0.995 (0.987–0.998) | 2% | 70.4 | 24.9 | 69.0 | 4 | good |

| WORK | |||||||||

| 0.06 | F | 25 ± 30 | 0.973 (0.938–0.988) | 4% | 24.1 | 19.8 | 54.9 | 11 | good |

| 0.08 | F | 20 ± 13 | 0.991 (0.980–0.996) | 3% | 28.9 | 13.7 | 38.0 | 8 | good |

| 0.11 | F | 18 ± 11 | 0.993 (0.983–0.997) | 3% | 24.9 | 10.4 | 28.9 | 6 | good |

| 0.13 | F | 25 ± 17 | 0.983 (0.962–0.993) | 4% | 28.5 | 18.6 | 51.6 | 11 | good |

| 0.06 | M | 26 ± 17 | 0.991 (0.977- 0.996) | 4% | 30.5 | 14.4 | 40.0 | 7 | good |

| 0.08 | M | 38 ± 33 | 0.971 (0.927–0.988) | 5% | 35.4 | 30.2 | 83.6 | 16 | good |

| 0.11 | M | 26 ± 29 | 0.981 (0.953–0.992) | 3% | 30.5 | 21.0 | 58.3 | 11 | good |

| 0.13 | M | 23 ± 19 | 0.988 (0.971–0.995) | 3% | 34.0 | 18.6 | 51.7 | 10 | good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Torrado, P.; Marina, M.; Salse-Batán, J. Assessing Reliability in Flywheel Squat Performance: The Role of Sex and Inertial Load. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2026, 11, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010004

Torrado P, Marina M, Salse-Batán J. Assessing Reliability in Flywheel Squat Performance: The Role of Sex and Inertial Load. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2026; 11(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorrado, Priscila, Michel Marina, and Jorge Salse-Batán. 2026. "Assessing Reliability in Flywheel Squat Performance: The Role of Sex and Inertial Load" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 11, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010004

APA StyleTorrado, P., Marina, M., & Salse-Batán, J. (2026). Assessing Reliability in Flywheel Squat Performance: The Role of Sex and Inertial Load. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 11(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010004