Heart Rate Variability Dynamics in Padel Players: Set-by-Set and Rest Period Changes in Relation to Match Outcome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

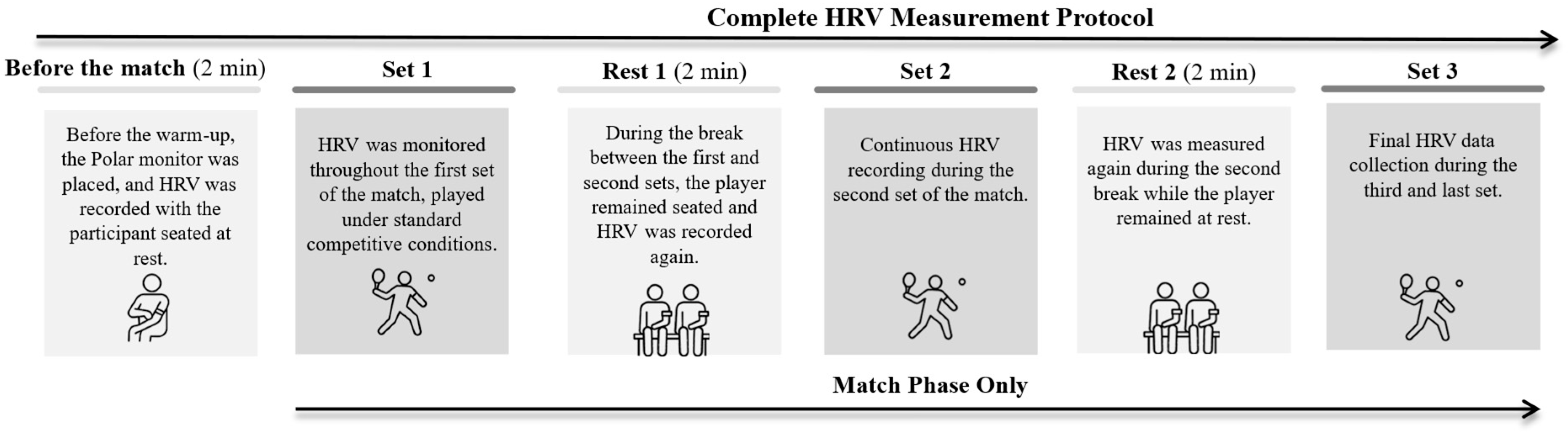

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Evolution of Physiological Responses Throughout the Match for All Players

4.2. Differences in Physiological Responses According to Match Outcome

4.3. Evolution of Physiological Responses During the Match According to Match Outcome

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HR | Heart rate |

| HRV | Heart rate variability |

| ANS | Autonomic nervous system |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

| PNS | Parasympathetic nervous system |

| PRE | Pre-match |

| S1, S2, S3 | Set 1, Set 2, Set 3 |

| R1, R2 | Rest period 1, Rest period 2 |

| Mean RR | Mean R–R interval |

| SDNN | Standard deviation of normalised R–R intervals |

| RMSSD | Root mean square of successive differences |

| LnRMSSD | Natural logarithm of RMSSD |

| STD HR | Standard deviation of heart rate |

| SD1 | Transverse axis of the Poincaré plot |

| SD2 | Longitudinal axis of the Poincaré plot |

| SS | Stress score |

| SNS/PNS ratio | Sympathetic–parasympathetic ratio |

| ES | Effect Size |

References

- Escudero-Tena, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; García-Rubio, J.; Ibáñez, S. Analysis of Game Performance Indicators during 2015–2019 World Padel Tour Seasons and Their Influence on Match Outcome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Llorca-Miralles, J. Physical Fitness in Young Padel Players: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Muñoz, D.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Grijota, F.J.; Chaparro, R.; Díaz, J. Motivos de La Práctica de Pádel En Relación a La Edad, El Nivel de Juego y El Género. SPORT TK Rev. Euroam. Cienc. Deport. 2018, 7, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courel Ibáñez, J.; Javier Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez, B.; García Benítez, S.; Echegaray, M. Evolución Del Pádel En España En Función Del Género y edad de Los Practicantes. Cult. Cienc. Deport. 2017, 12, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Benítez, S.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Pérez-Bilbao, T.; Felipe, J.L. Game Responses during Young Padel Match Play: Age and Sex Comparisons. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2017, 32, 1144–1149, Erratum in J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2018, 32, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Miguel, I.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Performance Analysis in Padel: A Systematic Review. J. Hum. Kinet. 2023, 89, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Bustamante-Sánchez, Á. Position and Ranking Influence in Padel: Somatic Anxiety and Self-Confidence Increase in Competition for Left-Side and Higher-Ranked Players When Compared to Pressure Training. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1393963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parraca, J.; Alegrete, J.; Villafaina, S.; Batalha, N.; Fuentes-García, J.P.; Muñoz, D.; Fernandes, O. Heart Rate Variability Monitoring during a Padel Match. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafaina, S.; Fuentes-García, J.P.; Fernandes, O.; Muñoz, D.; Batalha, N.; Parraca, J. The Impact of Winning or Losing a Padel Match on Heart Rate Variability. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 19, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Bustamante-Sánchez, Á. Pre and Post-Competitive Anxiety and Self-Confidence and Their Relationship with Technical-Tactical Performance in High-Level Men’s Padel Players. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1393980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, A.E.; Seps, B.; Beckers, F. Heart Rate Variability in Athletes. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 889–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picabea, J.M.; Cámara, J.; Yanci, J. Análisis de La Evolución de La Variabilidad de La Frecuencia Cardíaca Antes y Después de Un Partido de Tenis de Mesa En Función Del Resultado. Arch. Med. Deport. 2022, 39, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latino, F.; Limone, P.; Cassese, F.P.; Martinez-Roig, R.; Persico, A.; Tafuri, F. The Role of Heart Rate Variability in the Prevention of Musculoskeletal Injuries in Female Padel Players. Mol. Cell. Biomech. 2025, 22, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picabea, J.M.; Cámara, J.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Yanci, J. Comparison of Heart Rate Variability before and after a Table Tennis Match. J. Hum. Kinet. 2021, 77, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, J.C.; Rodas, G.; Capdevila, L. Heart-Rate Variability and Precompetitive Anxiety in Swimmers. Psicothema 2009, 21, 531–536. [Google Scholar]

- Javaloyes, A.; Sarabia, J.M.; Lamberts, R.P.; Moya-Ramon, M. Training Prescription Guided by Heart-Rate Variability in Cycling. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, A.; De la Cruz, B.; Garrido, M.A.; Medina, M.; Naranjo, J. Variabilidad de La Frecuencia Cardiaca En Un Deportista Juvenil Durante Una Competición de Bádminton de Máximo Nivel. Rev. Andal. Med. Deport. 2009, 2, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cruz, G.; Quezada-Chacon, J.T.; González-Fimbres, R.A.; Flores-Miranda, F.J.; Naranjo-Orellana, J.; Rangel-Colmenero, B.R. Effect of Consecutive Matches on Heart Rate Variability in Elite Volleyball Players. Rev. Psicol. Deport. 2017, 26, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilova, E.A. Heart Rate Variability and Sports. Hum. Physiol. 2016, 42, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, S.; Mosley, E.; Thayer, J.F. Heart Rate Variability and Cardiac Vagal Tone in Psychophysiological Research—Recommendations for Experiment Planning, Data Analysis, and Data Reporting. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboul, D.; Pialoux, V.; Hautier, C. The Impact of Breathing on HRV Measurements: Implications for the Longitudinal Follow-up of Athletes. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2013, 13, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodas, G.; Caballido, C.P.; Ramos, J.; Capdevila, L. Variabilidad de La Frecuencia Cardíaca: Concepto, Medidas y Relación Con Aspectos Clínicos (I). Arch. Med. Deport. 2008, XXV, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdillon, N.; Schmitt, L.; Yazdani, S.; Vesin, J.M.; Millet, G.P. Minimal Window Duration for Accurate HRV Recording in Athletes. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M. Monitoring Training Status with HR Measures: Do All Roads Lead to Rome? Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Jamotte, A.; Parraca, J.A.; Bustamante-Sánchez, Á. Heart Rate Variability Differences by Match Phase and Outcome in Elite Male Finnish Padel Players. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. JAMA 2025, 333, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettiarachchi, I.T.; Hanoun, S.; Nahavandi, D.; Nahavandi, S. Validation of Polar OH1 Optical Heart Rate Sensor for Moderate and High Intensity Physical Activities. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Carmona, I.; Gómez-Carmona, C.; Bastida-Castillo, A.; Pino-Ortega, J. Validez Del Dispositivo Inercial WIMU PROtm Para El registro de La Frecuencia Cardiaca En Un Test de Campo. SPORT TK Rev. Euroam. Cienc. Deport. 2017, 7, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, J.; De La Cruz, B.; Sarabia, E.; De Hoyo, M.; Domínguez-Cobo, S. Heart Rate Variability: A Follow-up in Elite Soccer Players Throughout the Season. Int. J. Sports Med. 2015, 36, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- López-Martín, E.; Ardura-Martínez, D. The Effect Size in Scientific Publication. Educ. XX1 2023, 26, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafaina, S.; Crespo, M.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Fuentes-García, J.P. Heart Rate Variability in Elite International ITF Junior Davis Cup Tennis Players. Biology 2023, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisschoff, C.A.; Coetzee, B.; Esco, M.R. Relationship between Autonomic Markers of Heart Rate and Subjective Indicators of Recovery Status in Male, Elite Badminton Players. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2016, 15, 658–669. [Google Scholar]

- Bisschoff, C.A.; Coetzee, B.; Esco, M.R. Heart Rate Variability and Recovery as Predictors of Elite, African, Male Badminton Players’ Performance Levels. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport. 2018, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Rivero, B.; Yanci, J.; Granados, C.; Picabea, J.M.; Ascondo, J. Evolution of Physiological Responses and Fatigue Analysis in Padel Matches According to Match Outcome and Playing Position. Sensors 2025, 25, 5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán-Márquez, R.; Onetti-Onetti, W.; Alvero-Cruz, J.; Castillo-Rodríguez, A. Win or Lose. Physical and Physiological Responses in Paddle Tennis Competition According to the Game Result. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport. 2022, 22, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, F.Y.; Flatt, A.A.; Pereira, L.A.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Loturco, I.; Esco, M.R. Ultra-Short-Term Heart Rate Variability Is Sensitive to Training Effects in Team Sports Players. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2015, 14, 602–605. [Google Scholar]

- Belinchon-de Miguel, P.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Psychophysiological, Body Composition, Biomechanical and Autonomic Modulation Analysis Procedures in an Ultraendurance Mountain Race. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | S1 | S2 | S3 | ES S1–S2 | ES S1–S3 | ES S2–S3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean RR (ms) | 385.98 ± 70.27 | 403.37 ± 36.86 | 422.22 ± 34.27 | −0.51 ** | −0.77 ** | −0.37 |

| SDNN (ms) | 38.38 ± 11.42 | 37.58 ± 8.98 | 41.93 ± 15.27 | 3.06 ** | −0.13 | 2.27 ** |

| RMSSD (ms) | 2.43 ± 0.57 | 2.62 ± 0.52 | 2.93 ± 0.45 | 0.37 * | 0.25 | 0.11 |

| LnRMSSD | 0.87 ± 0.22 | 0.94 ± 0.20 | 1.06 ± 0.16 | 0.36 * | 0.05 | 0.11 |

| STD HR (ms) | 13.83 ± 3.49 | 13.29 ± 2.81 | 13.59 ± 4.83 | −2.90 ** | −1.85 ** | −0.20 |

| SD1 (ms) | 1.72 ± 0.40 | 1.86 ± 0.37 | 2.07 ± 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.13 |

| SD2 (ms) | 54.25 ± 16.15 | 53.11 ± 12.70 | 59.24 ± 21.67 | −0.12 | −0.39 | −0.26 |

| SS | 18.64 ± 5.47 | 19.86 ± 4.70 | 31.23 ± 59.80 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.22 |

| SNS/PNS ratio | 11.21 ± 4.98 | 11.49 ± 5.09 | 15.47 ± 28.87 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Variables | PRE | R1 | R2 | ES PRE–R1 | ES PRE–R2 | ES R1–R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean RR (ms) | 566.31 ± 148.49 | 409.63 ± 77.64 | 432.54 ± 41.68 | 1.00 ** | 0.79 ** | 0.14 |

| SDNN (ms) | 67.04 ± 28.62 | 35.60 ± 12.69 | 39.09 ± 18.79 | 1.15 ** | 0.61 * | −0.03 |

| RMSSD (ms) | 5.01 ± 2.31 | 2.76 ± 0.88 | 3.27 ± 1.19 | −2.67 ** | −0.52 | −1.00 ** |

| LnRMSSD | 1.52 ± 0.48 | 0.98 ± 0.31 | 1.13 ± 0.33 | −1.90 ** | −0.42 | 1.87 ** |

| STD HR (ms) | 12.82 ± 6.26 | 12.20 ± 4.35 | 12.71 ± 6.27 | 0.44 ** | 0.31 | −0.08 |

| SD1 (ms) | 3.50 ± 1.56 | 1.90 ± 0.63 | 2.26 ± 0.85 | −2.12 ** | 1.99 ** | 2.21 ** |

| SD2 (ms) | 94.73 ± 40.47 | 50.31 ± 17.95 | 55.20 ± 26.63 | 2.74 ** | 0.09 | −1.55 ** |

| SS | 10.78 ± 4.46 | 21.16 ± 8.24 | 34.88 ± 59.63 | 2.86 ** | −0.46 | −1.00 ** |

| SNS/PNS ratio | 3.43 ± 2.38 | 12.42 ± 7.97 | 18.02 ± 29.39 | −2.13 ** | −0.39 | 0.77 ** |

| Variables | S1 | S2 | S3 | ES S1–S2 | ES S1–S3 | ES S2–S3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean RR (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 408.04 ± 31.81 | 414.64 ± 30.62 | 426.72 ± 29.92 | −0.44 * | −0.77 * | −0.23 |

| Lose | 358.11 ± 93.60 | 389.12 ± 39.86 | 416.60 ± 40.45 | −0.53 * | −0.89 * | −0.54 |

| ES | −0.50 ** | −0.73 ** | −0.29 | |||

| SDNN (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 42.03 ± 10.27 | 37.80 ± 7.09 | 38.18 ± 15.48 | 1.00 ** | 0.49 | −2.03 ** |

| Lose | 33.78 ± 11.38 | 37.30 ± 11.12 | 46.63 ± 14.59 | 2.75 ** | −0.62 | −2.62 ** |

| ES | −0.37 ** | −0.14 | 0.20 | |||

| RMSSD (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 2.59 ± 0.41 | 2.68 ± 0.44 | 2.94 ± 0.41 | 0.67 ** | 0.71 | 0.37 |

| Lose | 2.23 ± 0.67 | 2.55 ± 0.61 | 2.91 ± 0.53 | −0.17 | −0.28 | −0.10 |

| ES | −0.66* | −0.24 | −0.07 | |||

| LnRMSSD | ||||||

| Win | 0.94 ± 0.17 | 0.97 ± 0.17 | 1.07 ± 0.14 | −0.76 ** | 0.72 | 0.41 |

| Lose | 0.80 ± 0.26 | 0.91 ± 0.24 | 1.05 ± 0.19 | −0.19 | −0.28 | −0.10 |

| ES | −0.68 * | −0.30 | −0.12 | |||

| STD HR (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 14.21 ± 2.93 | 12.85 ± 2.78 | 11.99 ± 4.70 | −2.89 ** | −0.96 ** | 0.30 |

| Lose | 13.34 ± 4.12 | 13.85 ± 2.82 | 15.59 ± 4.47 *** | −2.91 ** | −2.27 ** | −0.69 |

| ES | −0.07 | 0.21 | 0.45 | |||

| SD1 (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 1.84 ± 0.29 | 1.90 ± 0.31 | 2.09 ± 0.29 | 0.52 * | 0.53 | 0.36 |

| Lose | 1.58 ± 0.48 | 1.81 ± 0.43 | 2.06 ± 0.38 | −0.28 | −0.50 | −0.06 |

| ES | −0.37 * | −0.13 | 0.00 | |||

| SD2 (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 59.41 ± 14.52 | 53.42 ± 10.03 | 53.91 ± 22.01 | 0.01 | −0.16 | 0.13 |

| Lose | 47.74 ± 16.08 | 52.72 ± 15.72 | 65.90 ± 20.64 | −0.33 | −0.61 | −0.69 |

| ES | −0.37 * | −0.14 | 0.20 | |||

| SS | ||||||

| Win | 17.69 ± 3.79 | 19.42 ± 4.07 | 42.94 ± 79.93 | 0.16 | 0.13 | −0.20 |

| Lose | 19.84 ± 6.99 | 20.41 ± 5.46 | 16.60 ± 5.31 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.78 |

| ES | 0.40 | 0.21 | −0.44 | |||

| SNS/PNS ratio | ||||||

| Win | 10.13 ± 3.66 | 10.64 ± 3.29 | 20.98 ± 38.55 | −0.15 | −0.20 | −0.38 |

| Lose | 12.57 ± 6.10 | 12.57 ± 6.66 | 8.57 ± 3.90 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.76 |

| ES | 0.27 | 0.13 | −0.22 |

| Variables | PRE | R1 | R2 | ES PRE–R1 | ES PRE–R2 | ES R1–R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean RR (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 583.32 ± 137.20 | 437.12 ± 36.91 | 434.36 ± 39.38 | 1.00 ** | 1.38 ** | 0.79 * |

| Lose | 544.83 ± 162.86 | 374.91 ± 100.22 | 430.27 ± 47.07 | 1.67 ** | 0.56 | −0.67 |

| ES | −0.07 | −0.86 ** | −0.10 | |||

| SDNN (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 68.79 ± 31.65 | 37.91 ± 10.10 | 39.70 ± 20.06 | 1.02 ** | 0.77 * | 0.07 |

| Lose | 64.82 ± 24.94 | 32.69 ± 15.15 | 38.32 ± 18.41 | 1.32 ** | 0.41 | −0.13 |

| ES | −0.15 | −0.39 | −0.07 | |||

| RMSSD (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 4.93 ± 2.47 | 3.08 ± 0.77 | 3.18 ± 1.24 | 1.93 ** | −0.27 | −1.00 ** |

| Lose | 5.11 ± 2.16 | 2.36 ± 0.87 | 3.38 ± 1.21 | 1.54 ** | −0.76 | −1.40 ** |

| ES | 0.08 | −0.89 ** | 0.16 | |||

| LnRMSSD | ||||||

| Win | 1.50 ± 0.49 | 1.10 ± 0.22 | 1.11 ± 0.30 | −2.08 ** | −0.22 | 1.00 ** |

| Lose | 1.55 ± 0.48 | 0.83 ± 0.34 | 1.16 ± 0.40 | −1.70 ** | −0.67 | 1.49 ** |

| ES | 0.12 | −0.97 ** | 0.14 | |||

| STD HR (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 12.62 ± 5.55 | 12.08 ± 3.34 | 12.80 ± 7.05 | 0.69 ** | 0.49 | −0.42 |

| Lose | 13.06 ± 7.21 | 12.35 ± 5.46 | 12.60 ± 5.61 | 0.23 | −0.09 | 0.33 |

| ES | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.03 | |||

| SD1 (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 3.45 ± 1.67 | 2.14 ± 0.56 | 2.19 ± 0.89 | −1.97 ** | 2.81 ** | 1.00 ** |

| Lose | 3.56 ± 1.45 | 1.61 ± 0.61 | 2.35 ± 0.86 | −2.35 ** | 1.50 ** | 1.85 ** |

| ES | 0.11 | −0.89 ** | 0.19 | |||

| SD2 (ms) | ||||||

| Win | 97.22 ± 44.75 | 53.56 ± 14.28 | 56.05 ± 28.46 | 3.09 ** | 0.35 | −1.53 ** |

| Lose | 91.59 ± 35.28 | 46.20 ± 21.43 | 54.13 ± 26.04 | 2.68 ** | −0.24 | −1.48 ** |

| ES | −0.15 | −0.39 | −0.07 | |||

| SS | ||||||

| Win | 10.80 ± 4.49 | 20.17 ± 6.36 | 43.67 ± 79.89 | 3.83 ** | −0.53 | −1.00 ** |

| Lose | 10.75 ± 4.54 | 22.41 ± 10.18 | 23.89 ± 13.47 | 2.51 ** | −0.51 | −1.66 ** |

| ES | −0.01 | 0.27 | −0.33 | |||

| SNS/PNS ratio | ||||||

| Win | 3.70 ± 2.82 | 10.12 ± 4.29 | 21.76 ± 38.49 | −3.08 ** | −0.56 | 0.55 |

| Lose | 3.09 ± 1.67 | 15.31 ± 10.43 | 13.34 ± 12.13 | −1.56 ** | −0.31 | 1.18 * |

| ES | −0.16 | 0.27 | −0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Picabea, J.M.; Marcos-Rivero, B.; Ascondo, J.; Yanci, J.; Granados, C. Heart Rate Variability Dynamics in Padel Players: Set-by-Set and Rest Period Changes in Relation to Match Outcome. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2026, 11, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010012

Picabea JM, Marcos-Rivero B, Ascondo J, Yanci J, Granados C. Heart Rate Variability Dynamics in Padel Players: Set-by-Set and Rest Period Changes in Relation to Match Outcome. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2026; 11(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010012

Chicago/Turabian StylePicabea, Jon Mikel, Bingen Marcos-Rivero, Josu Ascondo, Javier Yanci, and Cristina Granados. 2026. "Heart Rate Variability Dynamics in Padel Players: Set-by-Set and Rest Period Changes in Relation to Match Outcome" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 11, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010012

APA StylePicabea, J. M., Marcos-Rivero, B., Ascondo, J., Yanci, J., & Granados, C. (2026). Heart Rate Variability Dynamics in Padel Players: Set-by-Set and Rest Period Changes in Relation to Match Outcome. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 11(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010012