A Functional Recovery Program for Femoroacetabular Impingement in Two Professional Tennis Players: Outcomes at Two-Year Follow-Up

Abstract

1. Introduction

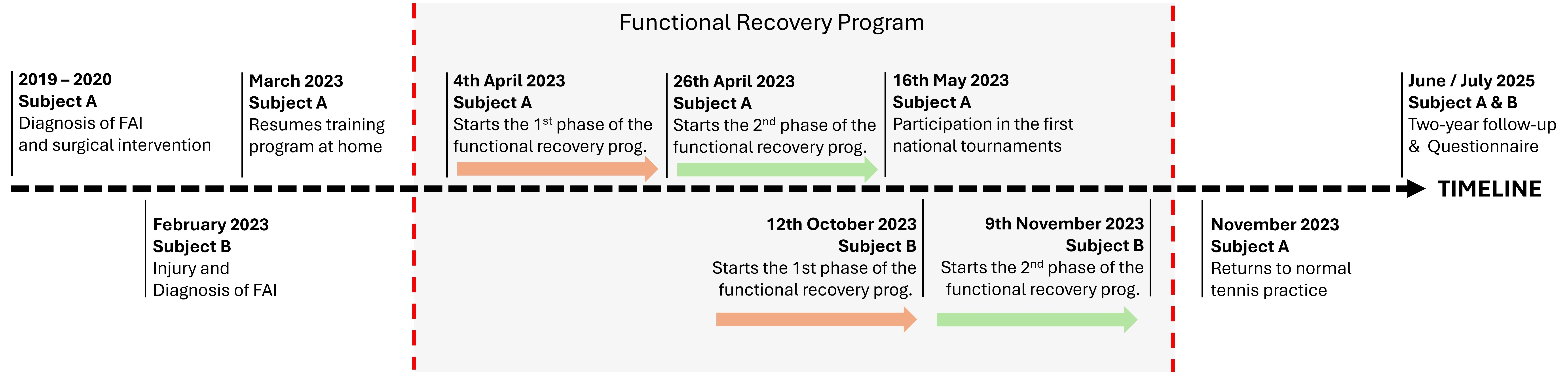

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.1.1. Subject A

2.1.2. Subject B

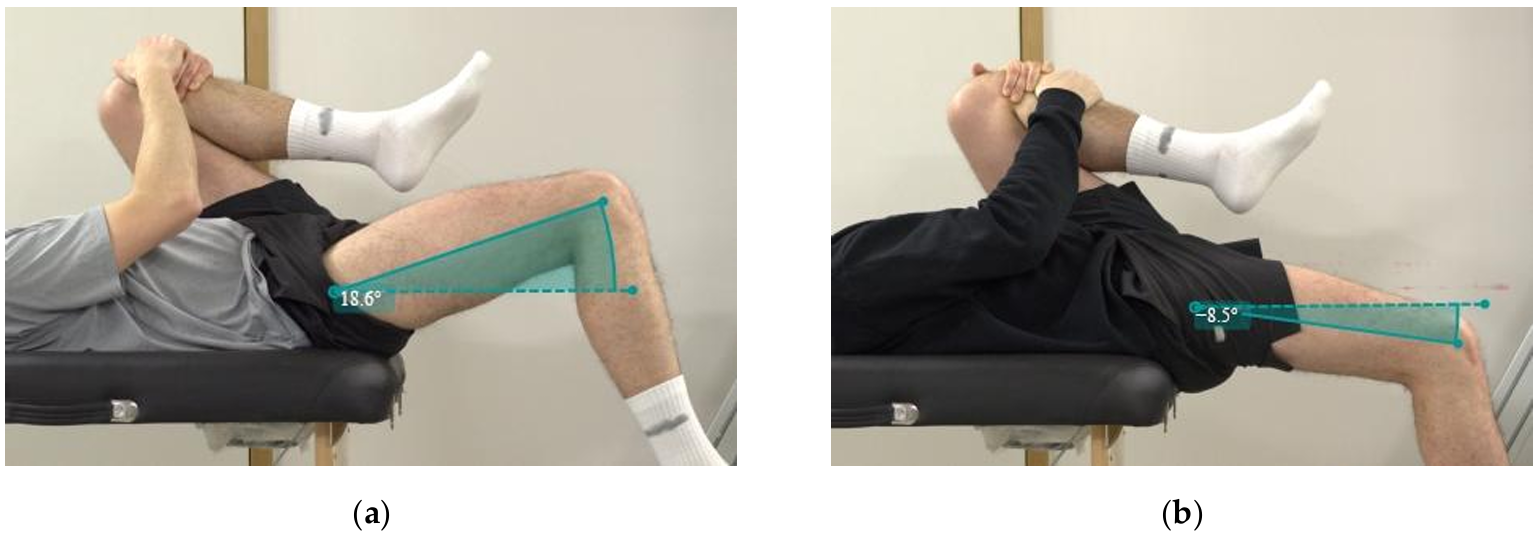

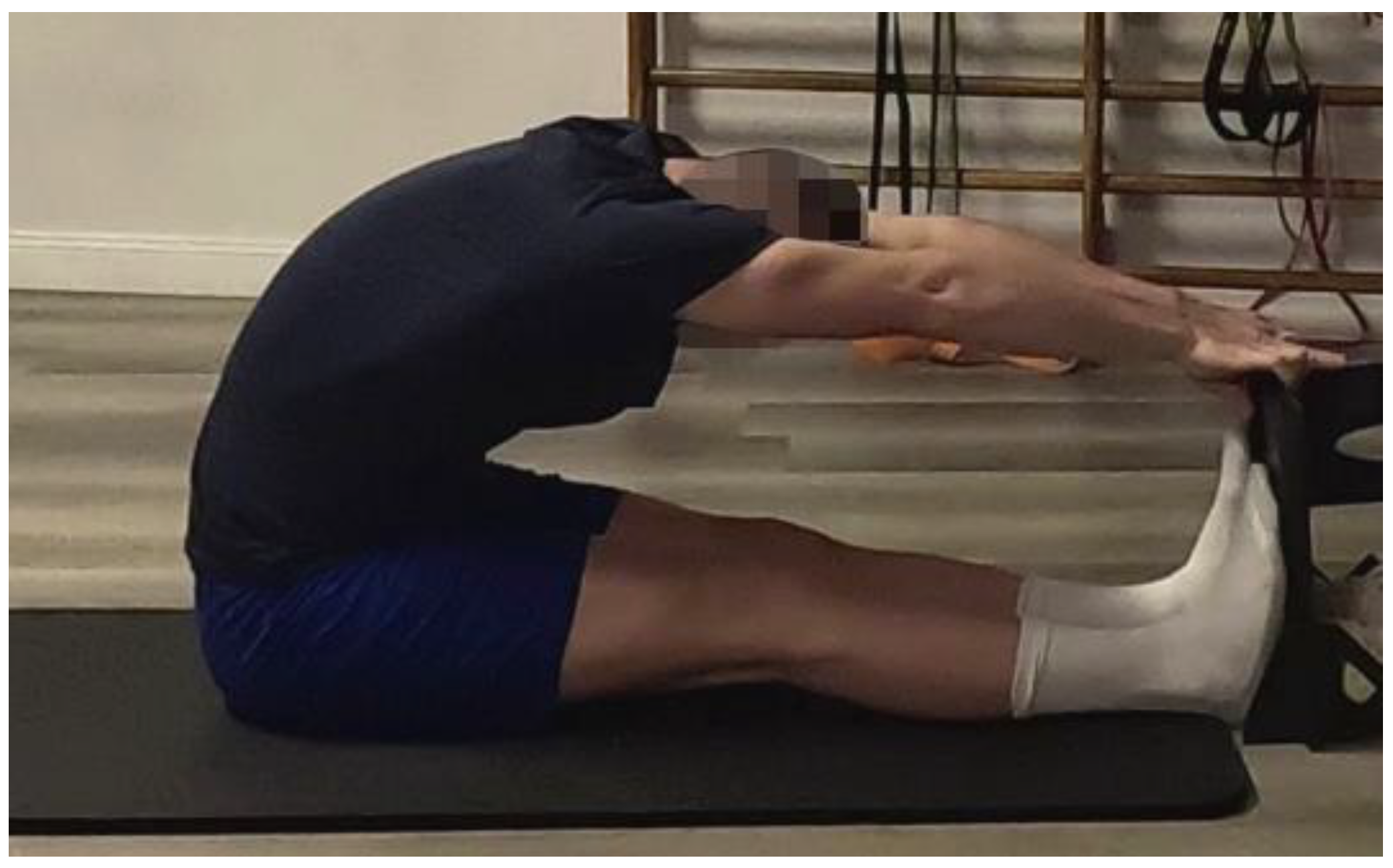

2.2. Range of Motion

2.3. Pain Level

2.4. Functional Recovery Program

2.4.1. First Phase

2.4.2. Second Phase

2.5. Two-Year Follow-Up Interview

3. Results

3.1. Range of Motion

3.2. Pain Level

3.3. Two-Year Follow-Up

- -

- “The influence of people from the close environment distracts from the competitive mode.”

- -

- “The mix of different doctors (physiotherapist) opinions so was searching for lot of opinions and tried everything. Psychologic as well was not easy because to feel pain for such a long time was not easy for me and it is not easy now as well but trying not to think about it and doing everything AO i can be pain free and return on the court.”

- -

- “Not good. Motivation dropping each time the pain is getting bigger.”

- -

- “The pain impacts my daily life a lot because was feeling it during my sleep and during walk or moving so couldn’t do normal things outside of the court. Program exercises were helping, but it is not easy mentally to do the same kind of things repeatedly for 2 Years and more. You must stay mentally strong, be motivated to keep the works so was not easy overall.”

- -

- “Maybe lack of discipline with prevention exercise and recovery.”

- -

- “Pain killers helped me little bit with pain, mobility exercise and relaxing tissue around the hip helped but not like that don’t feel it.”

4. Discussion

Future Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FAI | Femoroacetabular Impingement |

| ATP | Association of Tennis Professionals |

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scale |

| ROM | Range of Motion |

Appendix A

- Section 1—Perceived Barriers to Return to Competition

- What do you believe were the primary obstacles or challenges that prevented your return to competitive play within the two-year follow-up period?(Please consider physical, psychological, social, and logistical factors)

- To what extent did the following factors particularly hinder your progress or discourage you from returning to competitive play?(Please rate on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much)

- Fear of re-injury:

- Persistent pain or discomfort:

- Lack of confidence in physical ability:

- Psychological readiness (e.g., anxiety, frustration):

- Demands of the program:

- Lack of support from coaches/teammates:

- Financial constraints:

- Time commitments:

- Other (please specify):

- Section 2—Motivation for Return to Play

- At the beginning of your functional recovery program, how motivated were you to return to competitive play?(Please rate on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = Not at all motivated, 5 = Extremely motivated)

- What were your primary motivators for wanting to return to competitive play?(e.g., love of sport, team camaraderie, personal achievement, professional goals)

- How did your motivation to return to competitive play change over the two-year follow-up period? Please describe any shifts, increases, or decreases in your motivation and what factors contributed to these changes.

- Were there any external factors(e.g., support from family/friends, professional expectations, perceived pressure) that influenced your motivation, either positively or negatively?

- Section 3—Pain Experience over Time

- Please describe your pain experience immediately after the injury and during the initial phases of your functional recovery program.

- How did your pain level change throughout the two-year follow-up period?(e.g., did it decrease steadily, fluctuate, or remain constant?)

- How did your pain experience impact on your daily life, functional recovery program exercises, and overall outlook on returning to competitive play?

- Were there any specific strategies or interventions that you found particularly helpful or unhelpful in managing your pain?

- Section 4—Subjective Value of the Program

- Overall, how valuable did you find the functional recovery program you participated in?(Please rate on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = Not at all valuable, 5 = Extremely valuable)

- What aspects of the functional recovery program did you find most beneficial?(e.g., physical therapy, psychological support, education, access to facilities)

- What aspects of the functional recovery program do you believe could be improved to better support athletes in returning to competitive play?

- Did you feel adequately supported by the program staff (e.g., trainers, physical therapists, doctors, psychologists)? Please describe.

- If you were to advise another athlete going through a similar injury and functional recovery program, what would be the most important piece of advice you would offer regarding their involvement in such a program?

References

- Moreno-Pérez, V.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Sánchez-Migallón, V.; Domínguez, R.; Fernández-Elías, V.E.; Fernández-Fernández, J.; Pérez-López, A.; López-Samanes, A. The Acute Effect of Match-Play on Hip Range of Motion and Isometric Strength in Elite Tennis Players. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, W.B.; Safran, M. Tennis Injuries. Med. Sport Sci. 2005, 48, 120–137. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.C.; Ellenbecker, T.S.; Renstrom, P.A.; Windler, G.S.; Dines, D.M. Epidemiology of Injuries in Tennis Players. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2018, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvan, B.; Guillard, V.; Ramos-Pascual, S.; van Rooij, F.; Saffarini, M.; Nogier, A. Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Injuries in Tennis Players during the French Open Grand Slam Tournament from 2011 to 2022. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2024, 12, 23259671241241551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Sorel, A.; Touzard, P.; Bideau, B.; Gaborit, R.; DeGroot, H.; Kulpa, R. Can the Open Stance Forehand Increase the Risk of Hip Injuries in Tennis Players? Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2020, 8, 2325967120966297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, G.D.; Renstrom, P.A.; Safran, M.R. Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Injury in the Tennis Player. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotorro, A.; Philippon, M.; Briggs, K.; Boykin, R.; Dominguez, D. Hip Screening in Elite Youth Tennis Players. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dines, J. Tennis Injuries of the Hip and Thigh. In Tennis Medicine: A Complete Guide to Evaluation, Treatment, and Rehabilitation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 20, pp. 381–399. [Google Scholar]

- Schmaranzer, F.; Cerezal, L.; Llopis, E. Conventional and Arthrographic Magnetic Resonance Techniques for Hip Evaluation: What the Radiologist Should Know. In Seminars in Musculoskeletal Radiology; Thieme Medical Publishers: Stuttgart, Germany, 2019; Volume 23, pp. 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, R.; Parvizi, J.; Beck, M.; Leunig, M.; Nötzli, H.; Siebenrock, K.A. Femoroacetabular Impingement: A Cause for Osteoarthritis of the Hip. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.® 2003, 417, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapron, A.L.; Anderson, A.E.; Aoki, S.K.; Phillips, L.G.; Petron, D.J.; Toth, R.; Peters, C.L. Radiographic Prevalence of Femoroacetabular Impingement in Collegiate Football Players: AAOS Exhibit Selection. JBJS 2011, 93, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassarjian, A.; Brisson, M.; Palmer, W.E. Femoroacetabular Impingement. Eur. J. Radiol. 2007, 63, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salernitano, G.; D’Onofrio, R.; Colombo, V.; Bjelica, B.; Zelenović, M. Prevalenza Della Morfologia FAI Tipo Cam in Atleti Praticanti Sport Ad Alto Impatto-Ita. J. Sports Reh. Po. 2023, 10, 2306–2319, IBSN 007-11119-55. [Google Scholar]

- de Silva, V.; Swain, M.; Broderick, C.; McKay, D. Does High Level Youth Sports Participation Increase the Risk of Femoroacetabular Impingement? A Review of the Current Literature. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2016, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenrock, K.-A.; Ferner, F.; Noble, P.; Santore, R.; Werlen, S.; Mamisch, T.C. The Cam-Type Deformity of the Proximal Femur Arises in Childhood in Response to Vigorous Sporting Activity. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.® 2011, 469, 3229–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippon, M.J.; Ho, C.P.; Briggs, K.K.; Stull, J.; LaPrade, R.F. Prevalence of Increased Alpha Angles as a Measure of Cam-Type Femoroacetabular Impingement in Youth Ice Hockey Players. Am. J. Sports Med. 2013, 41, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agricola, R.; Heijboer, M.P.; Ginai, A.Z.; Roels, P.; Zadpoor, A.A.; Verhaar, J.A.; Weinans, H.; Waarsing, J.H. A Cam Deformity Is Gradually Acquired during Skeletal Maturation in Adolescent and Young Male Soccer Players: A Prospective Study with Minimum 2-Year Follow-Up. Am. J. Sports Med. 2014, 42, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, I.; Weir, A.; Langhout, R.; Waarsing, J.H.; Stubbe, J.; Kerkhoffs, G.; Agricola, R. The Relationship between the Frequency of Football Practice during Skeletal Growth and the Presence of a Cam Deformity in Adult Elite Football Players. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, N.A.; Guinea, N.S.; Molinero, J.G.; Bárez, M.G. Extra-Articular Hip Impingement: A Review of the Literature. Radiología (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 60, 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham, S.W.; Kolber, M.J. Rehabilitation after Hip Arthroscopy and Labral Repair in a High School Football Athlete. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2012, 7, 173. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Su, P.; Xu, T.; Zhang, L.; Fu, W. Conservative Therapy versus Arthroscopic Surgery of Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome (FAI): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2022, 17, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Torrente, A.; Puig-Torregrosa, J.; Montero-Navarro, S.; Sanz-Reig, J.; Morera-Balaguer, J.; Más-Martínez, J.; Sánchez-Mas, J.; Botella-Rico, J.M. Benefits of a Specific and Supervised Rehabilitation Program in Femoroacetabular Impingement Patients Undergoing Hip Arthroscopy: A Randomized Control Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer-Gardner, L.; Eischen, J.J.; Levy, B.A.; Sierra, R.J.; Engasser, W.M.; Krych, A.J. A Comprehensive Five-Phase Rehabilitation Programme after Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2014, 22, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoit, G.; Whelan, D.B.; Dwyer, T.; Ajrawat, P.; Chahal, J. Physiotherapy as an Initial Treatment Option for Femoroacetabular Impingement: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-Analysis of 5 Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Sports Med. 2020, 48, 2042–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, M.; Ohnishi, Y.; Utsunomiya, H.; Kanezaki, S.; Takeuchi, H.; Watanuki, M.; Matsuda, D.K.; Uchida, S. A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial Comparing Conservative Treatment with Trunk Stabilization Exercise to Standard Hip Muscle Exercise for Treating Femoroacetabular Impingement: A Pilot Study. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2019, 29, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, M.R.; Costantini, A. Treatment of Femoroacetabular Impingement and Labral Injuries in Tennis Players. In Tennis Medicine: A Complete Guide to Evaluation, Treatment, and Rehabilitation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- Parvaresh, K.C.; Wichman, D.M.; Alter, T.D.; Clapp, I.M.; Nho, S.J. High Rate of Return to Tennis after Hip Arthroscopy for Patients with Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome. Phys. Ther. Sport 2021, 51, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado, D.R.; Yelton, M.J.; Rosinsky, P.J.; Shapira, J.; Meghpara, M.B.; Lall, A.C.; Domb, B.G. Return to Play after Hip Arthroscopy among Tennis Players: Outcomes with Minimum Five-Year Follow-Up. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ATP Tour, Inc. ATP Tour. ATP World Tour. Available online: https://www.atptour.com/en (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Clapis, P.A.; Davis, S.M.; Davis, R.O. Reliability of Inclinometer and Goniometric Measurements of Hip Extension Flexibility Using the Modified Thomas Test. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2008, 24, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, R.P.; Oliveira, D.; Fanasca, M.A.; Vechin, F.C. Shortening of Hip Flexor Muscles and Chronic Low-Back Pain among Resistance Training Practitioners: Applications of the Modified Thomas Test. Sport Sci. Health 2023, 19, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Assessment of the Flexibility of Elite Athletes Using the Modified Thomas Test. Br. J. Sports Med. 1998, 32, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente-Pina, L.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, R.; Ferrández-Laliena, L.; Heredia-Jimenez, J.; Müller-Thyssen-Uriarte, J.; Monti-Ballano, S.; Hidalgo-García, C.; Tricás-Moreno, J.M.; Lucha-López, M.O. Validity and Reliability of Kinovea® for Pelvic Kinematic Measurement in Standing Position and in Sitting Position with 45° of Hip Flexion. Sensors 2025, 25, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmant, J. contributors Kinovea (0.9.5). 2021. Available online: https://www.kinovea.org (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Edriss, S.; Caprioli, L.; Campoli, F.; Manzi, V.; Padua, E.; Bonaiuto, V.; Romagnoli, C.; Annino, G. Advancing Artistic Swimming Officiating and Performance Assessment: A Computer Vision Study Using MediaPipe. Int. J. Comput. Sci. SPORT 2024, 23, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorga-Vega, D.; Merino-Marban, R.; Viciana, J. Criterion-Related Validity of Sit-and-Reach Tests for Estimating Hamstring and Lumbar Extensibility: A Meta-Analysis. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2014, 13, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Panzarino, M.; Padua, E. Flexibility Box Test. 2022. Available online: https://www.iris.uniroma5.it/handle/20.500.12078/10446 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Wagenmakers, E.-J. Jasp 0.18.3. 2024. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Cleland, J.A.; Childs, J.D.; Whitman, J.M. Psychometric Properties of the Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in Patients with Mechanical Neck Pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcioglu, O.; Topacoglu, H.; Dikme, O.; Dikme, O. A Systematic Review of the Pain Scales in Adults: Which to Use? Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoli, F.; Caprioli, L.; Cariati, I.; Edriss, S.; Romagnoli, C.; Bonaiuto, V.; Padua, E.; Annino, G. Functional Recovery Program for Femoroacetabular Impingement. 2025. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/9zz53jp4fb/2 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Casartelli, N.C.; Leunig, M.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Bizzini, M. Return to Sport after Hip Surgery for Femoroacetabular Impingement: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, G.D.; Preuss, F.; Mueller, J.; Delman, C.; Riboh, J.C.; Weeks, K.D.; Haffner, M.R. Return to Sport after Femoroacetabular Impingement. Orthop. Clin. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, S.; Sansone, M.; Augustsson, J. Full Recovery of Hip Muscle Strength Is Not Achieved at Return to Sports in Patients with Femoroacetabular Impingement Surgery. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2020, 28, 1276–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casartelli, N.C.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Leunig, M.; Bizzini, M. Femoroacetabular Impingement in Sports Medicine: A Narrative Review. Schweiz. Z. Für Sportmed. Sport. 2015, 63, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli, L.; Campoli, F.; Romagnoli, C.; Cariati, I.; Edriss, S.; Padua, E.; Bonaiuto, V.; Annino, G. Three Reasons for Playing the Tennis Forehand in Square Stance. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, N.; Martinez, C.E. Injury Prevention for Tennis Players: A Comprehensive Guide to Staying Injury-Free on the Court. 2025. Available online: https://books.google.it/books?id=HHtJEQAAQBAJ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

| Modified Thomas Test | Δ from the Physiological Value | Percentage Changes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions | Pre (°) | Post (°) | Pre (°) | Post (°) | |

| Subject A—Right | 18.6 | −8.5 | 29.5 | 2.4 | 91.9% |

| Subject B—Right | 10.0 | −9.0 | 20.9 | 1.9 | 90.9% |

| Subject B—Left | 3.6 | −19.4 | 14.5 | −8.5 | 158.6% |

| Average | 10.7 | −12.3 | 21.6 | −1.4 | 113.8% |

| Pain NRS—Subject “A” | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phases | 1st | 2nd | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily Levels | Median | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| Daily activities | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Playing Tennis | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Playing Tennis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pain NRS—Subject “B” | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phases | 1st | 2nd | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily Levels | Median | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| Daily activities | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Playing Tennis | NR | NR | NR | 1 | 1 | 1 | NR | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NR | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | 0 |

| Playing Tennis | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campoli, F.; Caprioli, L.; Cariati, I.; Edriss, S.; Romagnoli, C.; Bonaiuto, V.; Annino, G.; Padua, E. A Functional Recovery Program for Femoroacetabular Impingement in Two Professional Tennis Players: Outcomes at Two-Year Follow-Up. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10030309

Campoli F, Caprioli L, Cariati I, Edriss S, Romagnoli C, Bonaiuto V, Annino G, Padua E. A Functional Recovery Program for Femoroacetabular Impingement in Two Professional Tennis Players: Outcomes at Two-Year Follow-Up. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(3):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10030309

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampoli, Francesca, Lucio Caprioli, Ida Cariati, Saeid Edriss, Cristian Romagnoli, Vincenzo Bonaiuto, Giuseppe Annino, and Elvira Padua. 2025. "A Functional Recovery Program for Femoroacetabular Impingement in Two Professional Tennis Players: Outcomes at Two-Year Follow-Up" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 3: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10030309

APA StyleCampoli, F., Caprioli, L., Cariati, I., Edriss, S., Romagnoli, C., Bonaiuto, V., Annino, G., & Padua, E. (2025). A Functional Recovery Program for Femoroacetabular Impingement in Two Professional Tennis Players: Outcomes at Two-Year Follow-Up. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(3), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10030309