Patterns of Control: A Narrative Review Exploring the Nature and Scope of Technologically Mediated Intimate Partner Violence Among Generation Z Individuals

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Generation Z: The Digitally Engaged Generation

1.2. A Brief Description of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

1.3. The Impact of Social Media Engagement on Relationship Navigation

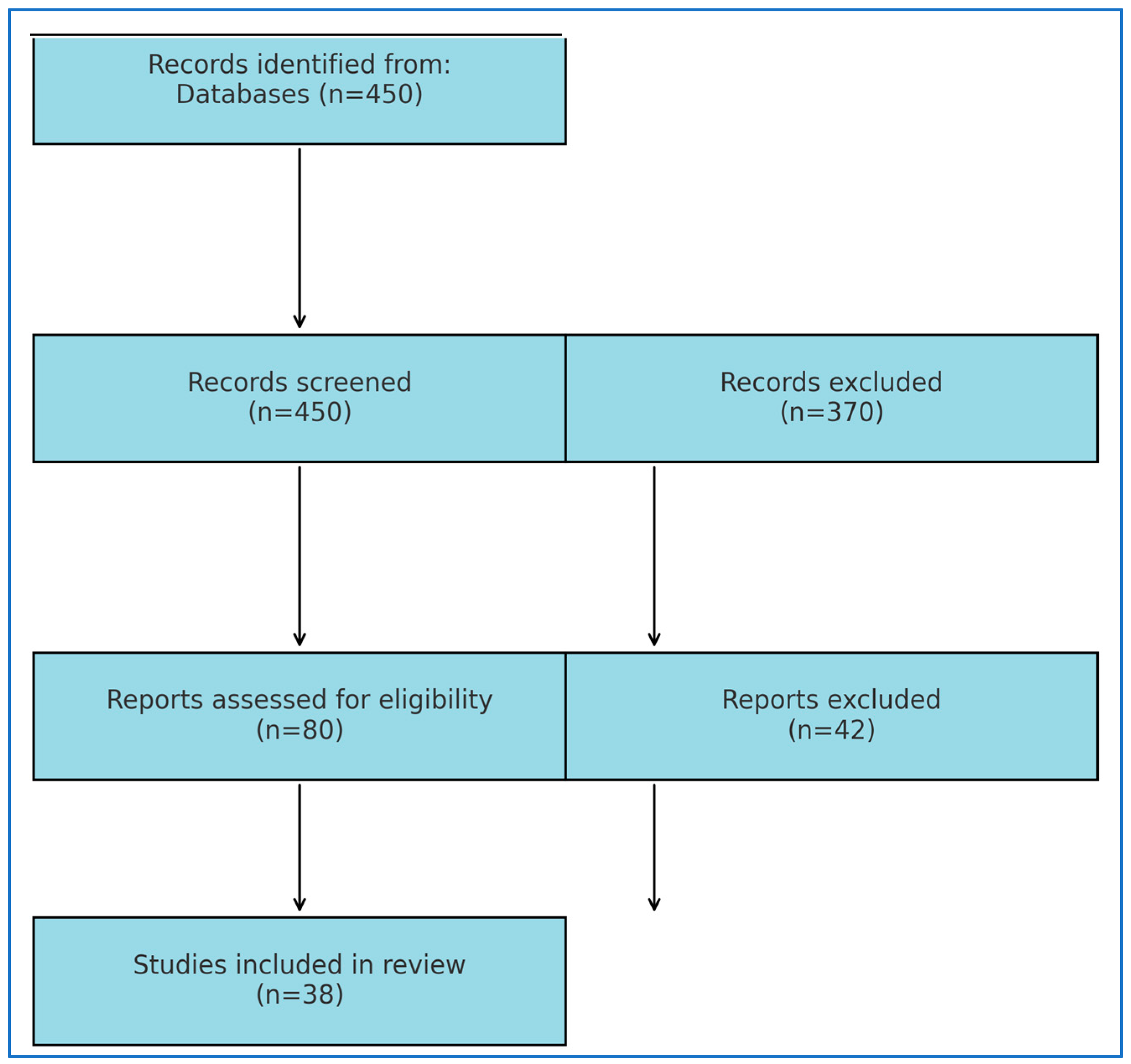

2. Methodology

3. Findings

3.1. Types of Technologically Facilitated Violence and Abuse

3.2. Generation Z’s Vulnerability Towards Technologically Mediated IPV

3.3. Impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Technologically Mediated IPV and Scope of Mitigation Services

3.4. Co-Occurrence of Online and Offline Violence

4. Technologically Based Violence Mitigation Services

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pew Research Center. Internet, Broadband Fact Sheet; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/ (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Dimock, M. Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins. Pew Research Center, 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Rogers, M.M.; Fisher, C.; Ali, P.; Allmark, P.; Fontes, L. Technology-Facilitated Abuse in Intimate Relationships: A Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 2210–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perrin, A.; Anderson, M. Share of U.S. Adults Using Social Media, Including Facebook, Is Mostly Unchanged Since 2018; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, E. What Years Are Gen X? A Detailed Breakdown of Generation Age Ranges. USA Today, 2022. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2022/09/02/what-years-gen-x-millennials-baby-boomers-generation Z/10303085002 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Coe, E.; Doy, A.; Enomoto, K.; Healy, C. Gen Z Mental Health: The Impact of Tech and Social Media. McKinsey Health Institute, 2023. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/mhi/our-insights/gen-z-mental-health-the-impact-of-tech-and-social-media (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Emezue, C. Digital or digitally delivered responses to domestic and intimate partner violence during COVID-19. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Melvin, E. Technology-Based Intimate Partner Violence Intervention Services for Generation Z Victims of Violence. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiding, M.J.; Chen, J.; Black, M.C. Intimate Partner Violence in the United States—2010; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.C. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 2002, 359, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicola, D.; Spaar, E. Intimate partner violence. Am. Fam. Physician 2016, 94, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Decker, M.R.; Peitzmeier, S.; Olumide, A.; Acharya, R.; Ojengbede, O.; Covarrubias, L.; Brahmbhatt, H. Prevalence and health impact of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence among female adolescents aged 15–19 years in vulnerable urban environments: A multi-country study. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, S58–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, L.C.; Morris, R.; Hegarty, K.; García-Moreno, C.; Feder, G. Categories and health impacts of intimate partner violence in the World Health Organization multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. National Statistics Domestic Violence Fact Sheet. 2020. Available online: https://ncadv.org/STATISTICS (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, S.; Eslen-Ziya, H.; Mangone, E. From offline to online violence: New challenges for the contemporary society. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2022, 32, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimani, A.; Gavine, A.; Moncur, W. An evidence synthesis of covert online strategies regarding intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N.; Flynn, A. Image-based sexual abuse: Online distribution channels and illicit communities of support. Violence Against Women 2019, 25, 1932–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, A.M.; Pereira, F.; Matos, M. Adolescents’ digital dating abuse and cyberbullying. In Adolescent Dating Violence: Outcomes, Challenges and Digital Tools; Caridade, S.M.M., Dinis, M.A.P., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, N.; Powell, A. Embodied harms: Gender, shame, and technology-facilitated sexual violence. Violence Against Women 2015, 21, 758–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, I.; McNealey, R.L. Nonconsensual distribution of intimate images: Exploring the role of legal attitudes in victimization and perpetration. J. Interpers. Violence 2023, 38, 5430–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslandes, S.F.; Silva, C.V.C.D.; Reeve, J.M.; Flach, R.M.D. Nude Leaking: From moralization and gendered violence to empowerment. Vazamento de Nudes: Da moralização e violência generificada ao empoderamento. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2022, 27, 3959–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S. “Weaponized Sexuality” to the Normalization of Sexual Violence: Rape Culture and the Non-Consensual Distribution of Intimate Imagery (NCDII). Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Winnipeg, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, R.; Batko, W. Right-Wing Authoritarianism, Empathy, and Judgements of Non-Consensual Distribution of Intimate Image (NCDII) Victims. J. Concurr. Disord. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, K.; Hilinski-Rosick, C.M.; Johnson, E.; Solano, G. Revenge porn victimization of college students in the United States: An exploratory analysis. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2017, 11, 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Klettke, B.; Hallford, D.J.; Mellor, D.J. Sexting prevalence and correlates: A systematic literature review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parti, K.; Sanders, C.E.; Englander, E.K. Sexting at an Early Age: Patterns and Poor Health-Related Consequences of Pressured Sexting in Middle and High School. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-Leiva, M.; Puente-Martínez, A.; Ubillos-Landa, S.; González-Castro, J.L.; Páez-Rovira, D. Off-and online heterosexual dating violence, perceived attachment to parents and peers and suicide risk in young women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.A.; Tolman, R.M.; Ward, L.M. Snooping and sexting: Digital media as a context for dating aggression and abuse among college students. Violence Against Women 2016, 22, 1556–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaureguizar, J.; Dosil-Santamaria, M.; Redondo, I.; Wachs, S.; Machimbarrena, J.M. Online and offline dating violence: Same same, but different? Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2024, 37, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, S.I.; Ha, T.; Anderson, S.F. “You liked that Instagram post?!” Adolescents’ jealousy and digital dating abuse behaviors in reaction to digital romantic relations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 153, 108111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragiewicz, M.; Woodlock, D.; Harris, B.; Reid, C. Technology-facilitated coercive control. In The Routledge International Handbook of Violence Studies; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 244–253. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, W.; Maras, M.H. Technology-facilitated coercive control: Response, redress, risk, and reform. Int. Rev. Law Comput. Technol. 2024, 38, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinder Pressroom. The Future of Dating Is Fluid. 2024. Available online: https://www.tinderpressroom.com/futureofdating#:~:text=This%20shift%20toward%20honesty,of%20Tinder%20is%20Gen%20Z (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Filice, E.; Abeywickrama, K.D.; Parry, D.C.; Johnson, C.W. Sexual violence and abuse in online dating: A scoping review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2022, 67, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adarsh, H.; Sahoo, S. Pornography and its impact on adolescent/teenage sexuality. J. Psychosexual Health 2023, 5, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester-Arnal, R.; Garcia-Barba, M.; Castro-Calvo, J.; Gimenez-Garcia, C.; Gil-Llario, M.D. Pornography consumption in people of different age groups: An analysis based on gender, contents, and consequences. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2023, 20, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, N.; Krämer, N.; Mikhailova, V.; Brand, M.; Krüger, T.H.; Vowe, G. Sexual interaction in digital contexts and its implications for sexual health: A conceptual analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 769732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Report. What Is Artificial Intelligence (AI)? IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/artificial-intelligence (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Houssami, N.; Kirkpatrick-Jones, G.; Noguchi, N.; Lee, C.I. Artificial Intelligence (AI) for the early detection of breast cancer: A scoping review to assess AI’s potential in breast screening practice. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2019, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, T. Bias in the Bot: Ai’s Relationship to Gender-Based Violence. NO MORE, 2025. Available online: https://www.nomore.org/bias-in-the-bot-ais-relationship-to-gender-based-violence/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Del Becaro, T. Generative artificial intelligence and gender biases: Between new tools and human rights. Stud. Soc. Sci. J. 2024, 17, 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- de Silva de Alwis, R. A rapidly shifting landscape: Why digitized violence is the newest category of gender-based violence. Rev. Juristes Sci. Po 2024, 25, 62. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4648409# (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Stanford Newsroom Report. Dangers of Deepfake: What to Watch For. University, IT, 2024. Available online: https://uit.stanford.edu/news/dangers-deepfake-what-watch (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Lindqvist, L. Book review: Digital Health and Technological Promise: A Sociological Inquiry. Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2022, 29, 116S–125S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweig, J.M.; Dank, M.; Yahner, J.; Lachman, P. The rate of cyber dating abuse among teens and how it relates to other forms of teen dating violence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, J.; Luo, X.; Lindsay, D.; Madre, N.; Paredes, J.; Penna, A.; Melley, E.; Garcia, T. Exploring the efficacy of ChatGPT in understanding and identifying intimate partner violence. Fam. Relat. 2025, 74, 1233–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrouz, R.; Vassos, S. Adolescents’ Experiences of Cyber-Dating Abuse and the Pattern of Abuse Through Technology, A Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2024, 25, 2814–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrajo, E. Cyber dating abuse and relational variables. In Adolescent Dating Violence: Outcomes, Challenges and Digital Tools; Caridade, S.M.M., Dinis, M.A.P., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Caridade, S.; Braga, T.; Borrajo, E. Cyber dating abuse (CDA): Evidence from a systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 48, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutbush, S.; Williams, J.; Miller, S.; Gibbs, D.; Clinton-Sherrod, M. Electronic dating aggression among middle school students: Demographic correlates and associations with other types of violence. In Proceedings of the American Public Health Association, Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 27–31 October 2012; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Marganski, A.; Melander, L. Intimate partner violence victimization in the cyber and real world: Examining the extent of cyber aggression experiences and its association with in-person dating violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 1071–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonard, K.E. “Technology was designed for this”: Adolescents’ perceptions of the role and impact of the use of technology in cyber dating violence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 105, 106211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonard, K.E.; Bowen, E.; Walker, K.; Price, S.A. “They’ll always find a way to get to you”: Technology use in adolescent romantic relationships and its role in dating violence and abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 2083–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, J.R.; Choi, H.J.; Brem, M.; Wolford-Clevenger, C.; Stuart, G.L.; Peskin, M.F.; Elmquist, J. The temporal association between traditional and cyber dating abuse among adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-González, L.; Calvete, E.; Orue, I. The role of acceptance of violence beliefs and social information pro cessing on dating violence perpetration. J. Res. Adolesc. 2018, 29, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love is Respect. Types of Abuse. Available online: https://www.loveisrespect.org/resources/types-of-abuse/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data, Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Ståhl, S.; Dennhag, I. Online and offline sexual harassment associations of anxiety and depression in an adolescent sample. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2020, 75, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, K.; Tarzia, L.; Valpied, J.; Murray, E.; Humphreys, C.; Taft, A.; Glass, N. An online healthy relationship tool and safety decision aid for women experiencing intimate partner violence (I-DECIDE): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e301–e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Youth-Centered Digital Health Interventions: A Framework for Planning, Developing and Implementing Solutions with and for Young People. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240011717 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Huang, K.Y.; Kumar, M.; Cheng, S.; Urcuyo, A.E.; Macharia, P. Applying technology to promote sexual and reproductive health and prevent gender based violence for adolescents in low and middle-income countries: Digital health strategies synthesis from an umbrella review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarron, E.; Wynn, R. Use of social media for sexual health promotion: A scoping review. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 32193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, L. Most Popular Dating Apps Worldwide 2024, by Numbers of Downloads. Statista, 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1200234/most-popular-dating-apps-worldwide-by-number-of-downloads/#:~:text=Most%20popular%20dating%20apps%20worldwide%202024%2C%20by%20number%20of%20downloads&text=With%20over%206.1%20million%20monthly,2.8%20million%20monthly%20downloads%2C%20respectively (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Hinge. Safe Dating Advice. Available online: https://help.hinge.co/hc/en-us/articles/360007194774-Safe-Dating-Advice (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Tinder. Reporting Profiles and Content. Available online: https://www.help.tinder.com/hc/en-us/articles/115003822043-Reporting-profiles-and-content (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Chayn. About Us. Available online: https://www.chayn.co/about (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Hebert, M.; Daspe, M.È; Lapierre, A.; Godbout, N.; Blais, M.; Fernet, M.; Lavoie, F. A meta- analysis of risk and protective factors for dating violence victimization: The role of family and peer interpersonal context. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 574–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; Borrajo, E.; Calvete, E. Partner abuse, control and violence through internet and smartphones: Characteristics, evaluation and prevention. Psychol. Pap. 2018, 39, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.L.; Reed, L.A.; Messing, J.T. Technology-based abuse: Intimate partner violence and the use of information communication technologies. In Mediating Misogyny: Gender, Technology, and Harassment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 209–227. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melvin, E.; Dasgupta, S. Patterns of Control: A Narrative Review Exploring the Nature and Scope of Technologically Mediated Intimate Partner Violence Among Generation Z Individuals. Sexes 2025, 6, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6040064

Melvin E, Dasgupta S. Patterns of Control: A Narrative Review Exploring the Nature and Scope of Technologically Mediated Intimate Partner Violence Among Generation Z Individuals. Sexes. 2025; 6(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelvin, Emily, and Satarupa Dasgupta. 2025. "Patterns of Control: A Narrative Review Exploring the Nature and Scope of Technologically Mediated Intimate Partner Violence Among Generation Z Individuals" Sexes 6, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6040064

APA StyleMelvin, E., & Dasgupta, S. (2025). Patterns of Control: A Narrative Review Exploring the Nature and Scope of Technologically Mediated Intimate Partner Violence Among Generation Z Individuals. Sexes, 6(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6040064