Abstract

This paper reexamines the contested categories of sex addiction and Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD) through a feminist-critical synthesis of 63 peer-reviewed articles published between 2000 and 2024. Rather than treating these diagnoses as neutral clinical entities, the review situates them within broader systems of normative regulation, emphasizing how psychiatric discourse, cultural anxieties, and digital infrastructures converge to define sexual deviance. The analysis is organized around the following three themes: (1) clinical ambivalence, where blurred thresholds of disorder mirror the opaque judgments of algorithmic moderation; (2) moral panic, which persists less as episodic reaction than as a durable strategy of governance embedded in media and platform logics; and (3) the pathologization of margins, whereby diagnostic and digital regimes disproportionately target queer, racialized, and gender-nonconforming sexualities. The paper introduces the concept of digital moral regulation to describe how platform architectures extend older traditions of moral governance, embedding cultural judgments into technical systems of visibility and suppression. By reframing CSBD as part of this regulatory formation, the review underscores that debates over compulsive sexuality are not solely matters of diagnostic precision, but of power: who defines harm, whose desires are legitimized, and how infrastructures translate cultural unease into regimes of control.

1. Introduction

The term sex addiction entered popular consciousness in the 1980s, emerging at the intersection of clinical psychology, evangelical recovery movements, and a rapidly expanding self-help industry []. Central to this emergence was the work of Patrick Carnes, whose Out of the Shadows [] introduced the idea of compulsive sexual behavior as a trauma-rooted disease akin to substance dependency. Drawing on addiction paradigms, Carnes proposed a four-phase cycle that centered preoccupation, ritualization, acting out, and despair and recast excessive sexual behavior not as moral failing but as a treatable illness. His model provided both a clinical language and a redemptive arc, bringing sexual distress under therapeutic jurisdiction while reinforcing a narrow conception of health tethered to self-control and restraint.

This paper does not treat sex addiction or its clinical cousin, Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD), as settled psychiatric facts. Instead, it approaches them as cultural technologies of regulation; categories whose meaning, application, and legitimacy are shaped as much by digital infrastructures and political values as by clinical need. Of particular concern here is how these diagnoses operate not only in therapeutic settings or media scandals, but in platform-mediated environments where sexual norms are algorithmically enforced.

To this end, we introduce the concept of digital moral regulation to describe how sexuality is increasingly governed through the technical architectures and policy logics of digital platforms in ways that reinforce cultural sexual norms and extend psychiatric discourse. While moral regulation has historically operated through religious, legal, or familial institutions, digital moral regulation works through content moderation systems, algorithmic visibility rules, and opaque community guidelines [] that define which sexual expressions are permitted, suppressed, or erased. We define digital moral regulation as the informal governance of sexual expression through platform infrastructures, including moderation algorithms, community guidelines, shadowbanning, and content visibility controls, that selectively restrict, stigmatize, or deplatform non-normative sexualities under the guise of neutrality, safety, or public morality.

By highlighting digital moral regulation, this paper offers a conceptual framework for understanding how sexual distress becomes clinically intelligible only within a larger ecology of normative enforcement. Diagnostic categories like CSBD do not emerge in isolation; they are co-produced by therapeutic discourse, media spectacle, and the regulatory structures of digital capitalism []. As Bronstein [] and others note, struggles over pornography and sexual morality in the 1970s and 1980s provided a cultural backdrop that anticipated later contests over sexual legitimacy, from clinical nosologies to platform moderation. What gets labeled as “addiction” is often not neutral; it is the product of cultural scripts, economic pressures, and algorithmic design. In this sense, what counts as pathology is determined less by clinical evidence than by the infrastructures of power and authority that govern sexuality across therapeutic, cultural, and digital domains.

Accordingly, this review aims to critically interrogate how diagnostic categories such as sex addiction and Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD) function as modes of normative regulation in digital contexts. Drawing on feminist and sociocultural perspectives, the review examines how psychiatric discourse, moral anxiety, and platform governance converge to define and manage sexual deviance.

2. Methods

This study employed a critical thematic literature synthesis to examine how “sex addiction” and Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD) are defined, contested, and mobilized across clinical, sociocultural, and digital literature. This approach emphasized interpretive judgment in identifying patterns across diverse fields, with particular attention to how diagnostic discourse intersects with media narratives and platform governance.

While this review incorporates structured search and screening strategies commonly associated with systematic reviews, its analytic orientation is critical and interpretive rather than aggregative. These procedures are presented here to enhance transparency and rigor within a feminist–critical synthesis.

2.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

A literature search was conducted across three databases (PsycINFO, Scopus, and JSTOR) between April and June 2025. To ensure completeness and comparability, we limited inclusion to studies published between 2000 and 2024, the last full calendar year available at the time of screening. Searches were limited to English-language articles.

The search used combinations of keywords and Boolean operators spanning three domains:

- Diagnostic language: “sex addiction,” “compulsive sexual behavior,” “hypersexual disorder,” “pornography addiction,” “behavioral addiction”.

- Sociocultural framings: “moral panic,” “pathologizing sexual behavior,” “sexual deviance,” “feminist theory,” “queer critique”.

- Digital context: “digital sexuality,” “platform governance,” “content moderation,” “OnlyFans,” “pornography use,” “algorithmic bias”.

This search yielded 499 initial results. Articles were screened in two phases. In the first phase, basic inclusion criteria were applied: studies had to be English-language, peer-reviewed journal articles. In the second phase, a manual review of abstracts and full texts was conducted to assess relevance. Studies were retained if they addressed at least one of the following dimensions:

- Conceptualization or diagnosis of sex addiction or CSBD.

- Cultural or media representations of compulsive sexual behavior.

- Theoretical critiques of sex addiction discourse (e.g., feminist, queer, intersectional).

- The role of digital platforms in shaping or regulating sexual behavior.

Analytic judgment was used to evaluate thematic fit, but all decisions were grounded in clearly defined research aims and a structured coding matrix. Final inclusion was limited to papers offering substantive theoretical, empirical, or discursive insights relevant to the research questions. This process resulted in a final sample of 63 articles for in-depth review.

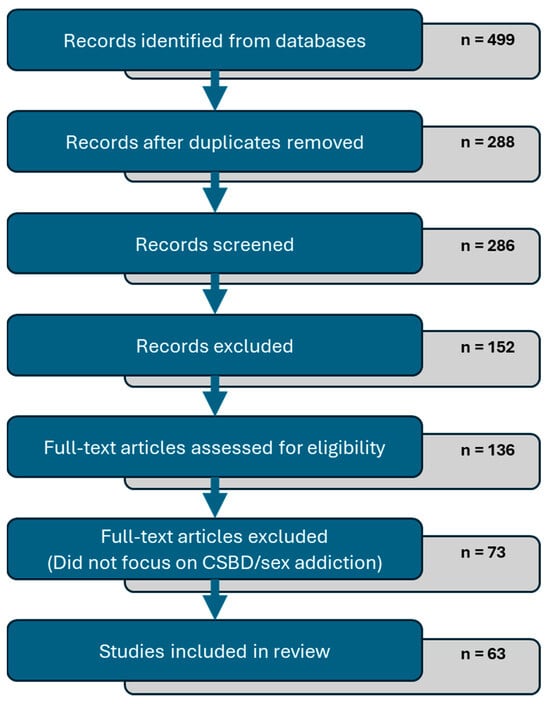

To enhance transparency, a PRISMA-style flow diagram (Figure 1) and summary table (Table S1) of included studies are provided. These are presented not as part of a formal systematic review but as support for the interpretive synthesis approach adopted here.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-style diagram illustrating the study selection process for the critical thematic synthesis on sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD). Adapted from the PRISMA 2020 statement [].

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they:

- Were commentaries or blog posts.

- Focused solely on unrelated disorders (e.g., substance abuse with no sexual behavior component).

- Lacked conceptual, empirical, or theoretical relevance to the research questions.

These criteria supported analytic focus, but the aim was not exhaustive coverage. Rather, the goal was to identify a body of work sufficient to interrogate conceptual and cultural debates.

2.3. Coding Strategy

All 63 included studies were read in full and coded manually. A coding matrix was developed based on both inductive themes and research-driven analytic questions. Each article was reviewed for how it addressed:

- Clinical framing and diagnostic legitimacy of sex addiction/CSBD.

- Moral or cultural narratives surrounding sexual behavior.

- Platform governance and digital moderation.

- Queer, feminist, or intersectional critiques of sexual regulation.

Codes were grouped into higher-order themes through iterative analysis. No software was used; analysis was conducted manually by one coder to preserve nuance in conceptual language.

3. Thematic Analysis

3.1. Theme 1: Clinical Ambivalence and the Politics of Disorder

The category of Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD) remains unsettled within psychiatric discourse, with its clinical boundaries and legitimacy persistently debated. Of the 63 articles reviewed, 29 expressed skepticism about the diagnosis, while 26 took supportive positions. The remaining 8 did not clarify a position relative to the diagnosis. Proponents emphasize evidence of impaired control, craving, and continued engagement despite negative consequences [,]. Case reports describe pharmacological interventions, including naltrexone and SSRIs [,], while Kolomanska’s [] review suggests preliminary promise for cognitive behavioral therapy. Collectively, these studies argue that CSBD aligns with models of behavioral addiction and merits inclusion in psychiatric nosology. However, the very contestation over where to draw diagnostic lines may reveal less about evidence than about authority, whose definitions of ‘impairment’ and ‘control’ are granted legitimacy, and whose forms of sexual intensity are cast as pathological.

Critics, however, caution against premature medicalization. Without clear biomarkers or consistent epidemiological thresholds, diagnostic proposals risk conflating high sexual desire or non-normative practices with pathology [,]. Methodological reviews identify weaknesses in measurement and sampling [], and Brand et al. [] insist that only severe cases producing significant impairment should qualify. Narrative reviews [] and the rejected DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition) proposal for “Hypersexual Disorder” [] underscore this ambivalence, showing how diagnostic debates have remained unresolved across decades of clinical research.

As a whole, this literature shows that debates over CSBD are less about uniform clinical findings than about competing claims to authority. Several authors highlight that these disputes are not only scientific but also cultural. Becker et al. [] observe that addiction research has historically encoded gendered and racial biases, positioning women’s distress or queer sexualities as dysfunction while normalizing heterosexual male behaviors. Cárdenas [] adds that trauma, poverty, and non-normative kinship arrangements are frequently reframed as hypersexuality, exemplifying how structural precarity can be individualized as disorder. These accounts suggest that the diagnostic uncertainty surrounding CSBD reflects deeper questions about the cultural regulation of sexuality, organized around ideals of restraint, monogamy, and reproductive propriety.

This uncertainty is not confined to psychiatry alone; it reverberates in digital infrastructures where moderation systems similarly draw opaque boundaries. Moderation systems on platforms such as TikTok and Instagram apply opaque thresholds of acceptability that determine which sexual expressions are visible and which are suppressed. Like diagnostic criteria, these thresholds are inconsistently applied []. The ambivalence of psychiatric criteria can be seen to find a parallel in algorithmic governance. This analysis shows that both create zones of suspicion where intensity, frequency, or non-normativity may be problematized. Clinical ambivalence, therefore, is difficult to understand in isolation from these broader infrastructures of regulation, in which psychiatric discourse and digital systems converge to shape what counts as legitimate desire.

What these debates ultimately reveal is not just ambivalence but a struggle over authority shaped by the questions of who has the power to define sexual excess as pathology, and on what terms. Supportive clinical studies often presume universals of “impairment” and “control” without interrogating how these standards are culturally loaded. Critics point to measurement flaws yet sometimes reproduce the same normative benchmarks. In both camps, assumptions about acceptable frequency, relational forms, or erotic objects remain unexamined. Reframing clinical ambivalence as a question of regulation, rather than evidence, exposes how psychiatry and platform systems converge in the production of categories that delimit truth about sexuality.

3.2. Theme 2: Moral Panic and Sexual Conservatism in the Diagnostic Discourse

A second major theme in the literature links debates over sex addiction and CSBD to longstanding cycles of moral panic and sexual conservatism. Of the 63 articles reviewed, 21 explicitly frame the category through the lens of moral panic or cultural anxiety. These studies highlight how concerns about pornography, masturbation, or compulsive Internet use have repeatedly been interpreted as signs of social decline rather than as empirically established disorders [,,]. The diagnostic contestation surrounding CSBD is thus not only a matter of psychiatric nosology but also part of broader cultural struggles over sexual norms.

The historical record suggests this point clearly. The emergence of “sex addiction” discourse in the 1980s coincided with the rise of the “family values” movement in the United States, the backlash against feminist sexual politics, and the entrenchment of conservative Christian critiques of pornography []. Griffiths [] describes the “Triple A engine” of Internet pornography (anonymity, accessibility, affordability) as central to its appeal and potential for compulsive use. Refracted through conservative moral discourse, these same features became a rallying point for anxiety about digital excess, producing a discursive link between online media and moral decline. These framings continue to appear in more recent literature, where online pornography is often constructed as uniquely dangerous, despite mixed evidence for its association with dysfunction [].

The global literature further underscores the culturally specific dimensions of this panic. Park et al. [] and Goswami and Singh [] show how “pornography addiction” discourses in Asia often operate as critiques of Western cultural invasion, framing the Internet as a vector of moral contamination. Awan et al. [] analyze pandemic-era anxieties about pornography, which were magnified by reports of increased online use during lockdowns. They note that these narratives were framed less in terms of measurable harm and more as expressions of collective anxiety about isolation, technology, and shifting norms. Across these cases, the invocation of “addiction” operates less as a clinical assessment than as a cultural shorthand for disorder in the social fabric. Read together, these studies suggest that panic discourse persists not because of its evidentiary weight, but because of its cultural utility.

This suggests that panic discourse is not simply reactive but productive; it supplies psychiatry with cultural scaffolding for otherwise fragile diagnostic claims, and it gives platforms a ready-made justification for restrictive moderation. Digital infrastructures now intensify these dynamics. Celebrity scandals, from Tiger Woods to Anthony Weiner, are not only reported but endlessly recycled in meme cycles, social media feeds, and online tabloids. Sex addiction becomes a narrative resource in these moments, simultaneously a spectacle of deviance and a pathway to redemption.

The shift to digital environments does not displace this logic but intensifies it, embedding panic into the infrastructures of visibility. Platforms accelerate this cycle, amplifying scandals, embedding them in searchable archives, and distributing them globally at unprecedented speed []. What was once a tabloid event now becomes a digital media ecology of outrage, commentary, and parody.

Several authors note that these dynamics disproportionately protect certain groups. Reay et al. [] suggest that white, middle-class men often mobilize the label of “sex addiction” to recast their transgressions as illness, thereby sidestepping moral condemnation. By contrast, racialized and queer sexualities tend to be portrayed as deviant without the protective veneer of medicalization. Here, moral panic and clinical ambivalence intersect; the same diagnosis that redeems powerful figures can stigmatize already marginalized populations.

Analyzed as whole, this body of work suggests that “sex addiction” functions not only as a psychiatric proposal but also as a cultural artifact of sexual conservatism. The concept has arguably thrived less because of its empirical validity than because it resonates with anxieties about technology, pornography, and shifting norms of intimacy. Platforms now operate as multipliers of these anxieties, embedding the logics of moral panic into the infrastructures of digital visibility. To understand CSBD solely as a contested diagnosis would thus miss the broader cultural dynamics in which it is entangled.

Describing these dynamics only as “panic” risks naturalizing their episodic quality, as if they were spontaneous cultural eruptions rather than carefully sustained regimes of governance. The persistence of panic discourse seems to point to its utility in mobilizing political capital, justifying restrictive policies, and legitimizing clinical expansion. In this sense, panic is may be interpreted not merely a recurring reaction but a strategy that platforms now operationalize by amplifying scandal and making moral judgment a durable feature of digital life. Recasting panic as infrastructure rather than moment clarifies why it endures: because it serves institutional interests, from psychiatry to platform capitalism, in stabilizing norms of propriety and exclusion.

3.3. Theme 3: Pathologizing the Margins—Diagnostic Boundaries and Cultural Visibility

A third cluster of the literature demonstrates how diagnostic categories like sex addiction and Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD) disproportionately mark certain groups as deviant. Of the 63 studies reviewed, 13 explicitly examined how marginal populations are pathologized through these discourses. Across this work, a recurring pattern emerges: heterosexual men’s compulsive behaviors are more likely to be framed as illness deserving of care, while queer, racialized, and gender-nonconforming communities are disproportionately constructed as excessive, immoral, or disordered [,].

These patterns are not incidental but rooted in longer histories of moral regulation. Endomba et al. [], examining African psychiatric contexts, show how colonial logics of sexual control persist in framing hypersexuality as disorder rather than as culturally situated practice. Similarly, Cárdenas [] highlights how poverty, trauma, or non-normative kinship arrangements are frequently reframed as hypersexuality, individualizing structural vulnerability as pathology. This historical layering suggests that pathologization reproduces entrenched hierarchies of race, gender, and class.

This pattern demonstrates that pathologization is not randomly distributed, but structured by existing hierarchies of race, gender, and sexuality. Those already positioned as socially precarious are most easily labeled excessive. In this sense, diagnostic categories function less as neutral descriptors than as technologies of stratification, distributing legitimacy unevenly and amplifying vulnerability among groups already subject to cultural suspicion.

Importantly, these studies underscore the distinction between distress and disapproval. Briken et al. [] caution that diagnostic expansion risks medicalizing consensual but non-normative practices such as BDSM, polyamory, or sex work, even in the absence of clinically significant harm. Becker et al. [] note that women’s reports of distress are frequently coded as evidence of disorder, while men’s sexual excess is reframed as treatable addiction. Across cases, the diagnostic lens confuses subjective suffering with deviation from normative standards of gender, class, or propriety.

Digital infrastructures extend and intensify these dynamics. Studies of TikTok, Instagram, and OnlyFans document how platform moderation disproportionately targets queer creators, sex workers, and educators, with their content flagged or removed even when not in violation of stated guidelines [,]. Euphemisms such as “seggs” on TikTok illustrate how LGBTQ+ users have developed workarounds to survive within these systems, highlighting that visibility itself has become a site of regulation.

The same asymmetries visible in clinical discourse reappear in platform moderation systems, where technical rules reproduce cultural biases at scale. The critical point is therefore not only that CSBD’s boundaries are blurry but that this blurriness is applied unevenly. For privileged subjects, diagnostic ambiguity functions as a buffer. White, middle-class men accused of misconduct can invoke “sex addiction” to recast their transgressions as illness, finding redemption in therapeutic narratives []. For marginalized subjects, the same ambiguity becomes a net of suspicion. Queer expression, sex work, or racialized intimacies are more readily read as pathological or unsafe, whether in clinical assessment or in algorithmic moderation. In this way, diagnostic categories and platform infrastructures converge to allocate legitimacy unevenly across sexual populations.

In our view, this illustrates a larger point that emerges from the literature: pathologization is not simply about categorizing symptoms but about governing populations. Diagnostic categories and moderation systems function as parallel infrastructures of suspicion, sorting which forms of sexuality are granted care, recognition, or visibility, and which are excluded as risk or disorder. Where psychiatry once individualized social difference as pathology, platforms now amplify this process by enforcing visibility hierarchies at scale. Together, they transform sexual nonconformity into a problem of governance rather than desire.

Taken as a whole, the literature demonstrates that pathologization disproportionately burdens those already marginalized, both within clinical discourse and digital environments. For some, “sex addiction” operates as a narrative of redemption; for others, it functions as a mechanism of exclusion. Taken together, these findings, echoing concerns raised by Briken [] and Cárdenas [], suggest that what is at stake in CSBD, then, is not only diagnostic ambivalence but the systematic allocation of legitimacy and illegitimacy across sexual populations. This theme reframes the problem. The question is not simply whether CSBD is clinically valid, but whose sexualities it renders visible, treatable, and legitimate, and whose it renders pathological, silenced, or erased.

4. Discussion and Limitations

4.1. Discussion

The analysis of 63 articles across three thematic clusters demonstrates that sex addiction and CSBD are not simply unstable diagnostic categories but part of a broader system of digital moral regulation. By this term, we mean the processes through which platforms, via moderation rules, algorithmic thresholds, and the politics of visibility, govern sexual expression in ways that converge with and extend psychiatric discourse. Where classic theories of moral panic [,] described episodic waves of public anxiety, digital moral regulation names a more enduring formation: the embedding of those anxieties into the infrastructures of digital media that regulate what can be seen, circulated, and legitimated as desire.

These dynamics are best understood genealogically. Earlier practices of sexual regulation, particularly during the 1970s porn wars, anticipated the logics now instantiated in platform governance. Bronstein [] and others document how anti-porn feminist campaigns and conservative “family values” coalitions sought to curb the circulation of sexual materials through obscenity law, zoning ordinances, and community standards. Such interventions treated sexual representation as both a moral danger and a social pollutant, requiring regulation for the sake of public order. Today’s platforms reproduce these traditions in technical form through shadowbanning, content removal, and algorithmic downranking. These can be interpreted as performing the classificatory functions once exercised by courts, publishers, and civic authorities. In this sense, digital moral regulation can be understood as the continuation and transformation of longstanding regulatory regimes, translating cultural anxieties into opaque, automated systems.

In this analysis, the platform governance literature helps clarify these mechanisms. Gillespie [] argues that moderation decisions, though presented as technical, are always moral acts of boundary-setting. Roberts [] highlights the hidden labor of moderators, who enact cultural norms of acceptability at industrial scale. Gorwa, Binns, and Katzenbach [] conceptualize platform governance as a hybrid regulatory system, where private corporations exercise quasi-legal authority over visibility. Work on sexuality and digital culture sharpens this perspective. Tiidenberg [] shows how sexual self-expression is policed through aesthetic and normative filters, while Franco [] analyzes the infrastructural governance of sex work, where moderation rules intersect with payment processors and hosting services to restrict what forms of labor and intimacy can survive online.

Table 1 offers a comparative snapshot of moderation practices across four major platforms. TikTok and Instagram enforce vague or automated guidelines that disproportionately suppress queer and sex-education content []. OnlyFans appears permissive on paper but faces external pressures from payment processors that constrain erotic labor markets [,]. X (formerly Twitter) is often noted for its tolerance of explicit content, yet its moderation remains inconsistent and chaotic. For example, De Keulenaar et al. [] trace how Twitter’s conception of objectionable speech has changed over time, revealing shifting norms, opaque boundary decisions, and selective enforcement across content types. These cases suggest that infrastructural governance may not merely reflect social anxieties but actively operationalizes them, embedding moral judgments in platform design and policy.

Table 1.

Comparison of Platform Moderation Policies for Sexual Content.

As a whole, these comparisons indicate that moderation practices are not isolated quirks of individual platforms but part of a broader ecology of governance. What matters is not only how TikTok, Instagram, OnlyFans, or X set their rules, but how those rules resonate with older struggles over the policing of sexual behavior. By embedding judgments about propriety into algorithms and guidelines, platforms may be seen as taking on functions once performed by psychiatry, law, or religion. To account for these convergences, we turn to the framework of digital moral regulation, which makes visible how moderation logics intersect with clinical ambivalence, moral panic, and the pathologization of marginalized sexualities.

Digital moral regulation both builds on and departs from existing literature. Moral panic theory remains invaluable for showing how sexual anxieties crystallize in moments of cultural upheaval. However, its episodic framing cannot capture the infrastructural embedding of those anxieties in technical systems. Scholarship on clinical ambivalence has shown that CSBD is unstable and contested, but often treats psychiatry as an autonomous professional field. The findings here suggest instead that psychiatric uncertainty resonates with platform governance in that both rely on blurred thresholds, both produce zones of suspicion, and both translate normative assumptions into regimes of regulation. Similarly, the literature on sexual conservatism rightly identifies how diagnoses reproduce heteronormative and patriarchal norms, but digital moral regulation highlights how those norms are not only discursively asserted but materially instantiated in algorithmic architectures that shape what is visible, searchable, and monetizable.

The three thematic findings illustrate this convergence. Clinical debates about where to draw the line between high desire and pathology mirror platform moderation systems that must decide which sexual expressions remain online and which are removed. Moral panics, once enacted in tabloids or courtrooms, are now accelerated and archived by platforms, creating enduring ecologies of outrage, spectacle, and redemption. Pathologization of margins, long evident in psychiatry’s treatment of queer, racialized, and non-normative sexualities, is intensified by digital moderation practices that disproportionately target the very groups most vulnerable to clinical overdiagnosis. Across each domain, psychiatry and platforms do not merely coexist but can be seen to reinforce one another, converging into a multi-sited system of governance.

Framing CSBD as a case of digital moral regulation has important implications. First, it suggests that diagnostic categories cannot be assessed on clinical validity alone; they must be situated within the digital infrastructures that regulate sexual expression at scale. Second, it underscores the urgency of transparency and accountability in platform governance, where algorithmic decisions about visibility can shape reputations and communities as profoundly as psychiatric labels. Finally, it calls for a justice-oriented clinical practice that recognizes the convergences between psychiatric and digital regulation and resists reinforcing them. Digital moral regulation, in this sense, is not merely descriptive but conceptual. It provides a framework for interrogating how older traditions of moral regulation have been reconstituted in the digital age, where platforms and psychiatry together can shape and delimit the boundaries of sexual legitimacy.

4.2. Limitations

As with all qualitative syntheses, this study reflects both the strengths and constraints of interpretive methodology. First, while the database searches were structured and inclusion criteria clearly defined, the final selection of 63 articles necessarily involved subjective judgment, especially regarding thematic relevance and conceptual alignment with the study’s research questions. Although every effort was made to ensure transparency and rigor, the coding process was interpretive and reflects the analytic lens of the author.

Second, the review focused exclusively on English-language, peer-reviewed journal articles, which may have excluded valuable perspectives from non-English contexts, grey literature, or community-based knowledge production, especially from activist, sex worker, or queer organizing spaces that often critique diagnostic norms from outside academic institutions.

Third, while this review draws connections across disciplines and theoretical frameworks, it does not conduct a meta-ethnography or formal comparative analysis between empirical outcomes. Instead, it privileges discursive synthesis over methodological triangulation. This choice reflects the project’s critical and feminist orientation, but may limit generalizability for readers seeking evidence-based consensus on CSBD or sex addiction treatment efficacy.

4.3. Future Directions

Future research should extend this inquiry in at least three directions. First, empirical studies should examine how clinicians apply CSBD in practice, including how diagnostic criteria are interpreted across lines of race, gender, and sexual identity. Second, more work is needed to interrogate the political economy of platform moderation, especially as tech companies increasingly mediate access to sexual information, expression, and community. Third, scholars should continue to develop justice-oriented frameworks that center the voices of those most impacted by sexual regulation, particularly queer, trans, and racialized users whose experiences of desire, pleasure, and harm have long been overlooked or misrepresented in diagnostic discourse.

These directions point to the possibility of alternative frameworks: ones less invested in naming disorder than in recognizing power. The conclusion that follows makes this argument explicit.

5. Conclusions

This review demonstrates that debates over sex addiction and its clinical counterpart, Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder, reveal less about diagnostic precision than about the governance of sexuality. Across 63 articles, CSBD emerges not simply as a contested clinical entity but as part of a broader regulatory formation that disciplines desire through clinical discourse, cultural anxiety, and digital infrastructures.

The analysis positions digital moral regulation as the conceptual frame that best captures this convergence. Rather than focusing on the validity of diagnostic categories alone, digital moral regulation foregrounds how psychiatric discourse and platform architectures jointly embed normative judgments into systems of visibility and suppression.

The consequences of this convergence are unevenly distributed. Clinical and digital frameworks often reinforce assumptions of gender, race, class, and propriety, while platform moderation disproportionately targets queer, trans, racialized, and sex-working communities. What counts as deviant, disordered, or even speakable may be determined as much by infrastructural governance as by clinical judgment.

The implications extend across domains. For scholars, the digital moral regulation lens shifts attention from nosological debates to the infrastructures that sustain cultural anxieties. For clinicians, it underscores the need for justice-oriented practice that resists aligning with digital exclusions. And for platform governance, it highlights the urgency of transparency and accountability in decisions that shape sexual legitimacy at scale.

To study sex addiction today is therefore to study not only a contested diagnosis but also the sociotechnical conditions through which sexuality is governed. Diagnosis is not only about symptoms; it is also about power; about who defines harm, whose desires are erased, and how infrastructures translate cultural unease into regimes of regulation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sexes6040063/s1, Table S1: Summary of Included Studies in Critical Thematic Synthesis. References [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the journal reviewers for their constructive feedback, which strengthened the clarity and rigor of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Reay, B.; Attwood, N.; Gooder, C. Inventing Sex: The Short History of Sex Addiction. Sex. Cult. 2013, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnes, P. Out of the Shadows: Understanding Sexual Addiction, 3rd ed.; Hazelden Information & Educati: Center City, MN, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, T. Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. The History of Sexuality, 1st ed.; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein, C. Battling Pornography: The American Feminist Anti-Pornography Movement, 1976–1986, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.W.; Voon, V.; Potenza, M.N. Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an addiction? Addiction 2016, 111, 2097–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, T.; Laier, C.; Brand, M.; Hatch, L.; Hajela, R. Neuroscience of Internet Pornography Addiction: A Review and Update. Behav. Sci. 2015, 5, 388–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostwick, J.M.; Bucci, J.A. Internet Sex Addiction Treated with Naltrexone. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2008, 83, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, T.; Din, J.S. Compulsive Sexual Behavior and Alcohol Use Disorder Treated with Naltrexone: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e25804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomanska, A. (024) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder. J. Sex. Med. 2023, 20, qdad060.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, K.L.; Grant, J.E. Compulsive sexual behavior: A review of the literature. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. The Concept of “Hypersexuality” in the Boundary between Physiological and Pathological Sexuality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, J.B.; Hoagland, C.; Lee, B.N.; Grant, J.T.; Davison, P.; Reid, R.C.; Kraus, S.W. Sexual Addiction 25 Years On: A Systematic and Methodological Review of Empirical Literature and an Agenda for Future Research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 82, 101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Rumpf, H.J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Müller, A.; Stark, R.; King, D.L.; Goudriaan, A.E.; Mann, K.; Trotzke, P.; Fineberg, N.A.; et al. Which conditions should be considered as disorders in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD–11) designation of “other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors”? J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 11, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnie, J.; Reavey, P. Problematic pornography use: Narrative review and a preliminary model. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2020, 35, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafka, M.P. Hypersexual Disorder: A Proposed Diagnosis for DSM-V. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010, 39, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, J.B.; McClellan, M.; Reed, B.G. Sociocultural context for sex differences in addiction. Addict. Biol. 2016, 21, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cárdenas, M. Poetic Operations: Trans of Color Art in Digital Media; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2022; Volume 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D. Internet sex addiction: A review of empirical research. Addict. Res. Theory 2012, 20, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, H.A.; Aamir, A.; Diwan, M.N.; Ullah, I.; Pereira-Sanchez, V.; Ramalho, R.; Orsolini, L.; de Filippis, R.; Ojeahere, M.I.; Ransing, R.; et al. Internet and Pornography Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Presumed Impact and What Can Be Done. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 623508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, V.; Singh, D.R. Internet Addiction among Adolescents: A Review of the Research. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2016, 3, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alarcón, R.; De La Iglesia, J.I.; Casado, N.M.; Montejo, A.L. Online Porn Addiction: What We Know and What We Don’t—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Wilson, G.; Berger, J.; Christman, M.; Reina, B.; Bishop, F.; Klam, W.P.; Doan, A.P. Is Internet Pornography Causing Sexual Dysfunctions? A Review with Clinical Reports. Behav. Sci. 2016, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N.; Hepp, A. The Mediated Construction of Reality; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Briken, P.; Bőthe, B.; Carvalho, J.; Coleman, E.; Giraldi, A.; Kraus, S.W.; Lew-Starowicz, M.; Pfaus, J.G. Assessment and treatment of compulsive sexual behavior disorder: A sexual medicine perspective. Sex. Med. Rev. 2024, 12, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endomba, F.T.; Demina, A.; Meille, V.; Ndoadoumgue, A.L.; Danwang, C.; Petit, B.; Trojak, B. Prevalence of internet addiction in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiidenberg, K. Sex, power and platform governance. Porn. Stud. 2021, 8, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, R.S. “Controlling the keys to the Golden City”: The payment ecosystem and the regulation of adult webcamming and subscription-based fan platforms. New Media Soc. 2024, 14614448241303465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers; MacGibbon and Kee: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, P.; Goode, E.; Ben-Yehuda, N. Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance. Contemp Sociol. 1996, 25, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.T. Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gorwa, R.; Binns, R.; Katzenbach, C. Algorithmic content moderation: Technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance. Big Data Soc. 2020, 7, 205395171989794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, T. Content moderation, AI, and the question of scale. Big Data Soc. 2020, 7, 2053951720943234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comella, L. Vibrator Nation: How Feminist Sex-Toy Stores Changed the Business of Pleasure; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasonen, S. Many Splendored Things: Thinking Sex and Play; Goldsmiths Press: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Keulenaar, E.; Magalhães, J.C.; Ganesh, B. Modulating moderation: A history of objectionability in Twitter moderation practices. J. Commun. 2023, 73, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frascella, J.; Potenza, M.N.; Brown, L.L.; Childress, A.R. Shared brain vulnerabilities open the way for nonsubstance addictions: Carving addiction at a new joint? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1187, 294–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E.; Bancroft, J. The Dual Control Model of Sexual Response: A Scoping Review, 2009–2022. J. Sex. Res. 2023, 60, 948–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacy, A.W.; Wiers, R.W. Implicit Cognition and Addiction: A Tool for Explaining Paradoxical Behavior. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antons, S.; Engel, J.; Briken, P.; Krüger, T.H.C.; Brand, M.; Stark, R. Treatments and interventions for compulsive sexual behavior disorder with a focus on problematic pornography use: A preregistered systematic review. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 643–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, C.; Cabé, J.; Cabé, N.; Bertsch, I.; Brousse, G.; Pereira, B.; Moulin, V.; Barrault, S. Measuring craving: A systematic review and mapping of assessment instruments. What about sexual craving? Addiction 2023, 118, 2277–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efrati, Y.; Kraus, S.W.; Kaplan, G. Common Features in Compulsive Sexual Behavior, Substance Use Disorders, Personality, Temperament, and Attachment—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Banerjee, D. Neurobiology of Sex and Pornography Addictions: A Primer. J. Psychosexual Health 2022, 4, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewska, E.; Lew-Starowicz, M. Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder–the evolution of a new diagnosis introduced to the ICD-11, current evidence and ongoing research challenges. Wiedza. Med. 2021, 3, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahithya, B.R.; Kashyap, R.S. Sexual Addiction Disorder—A Review with Recent Updates. J. Psychosexual Health 2022, 4, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassover, E.; Weinstein, A. Should compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) be considered as a behavioral addiction? A debate paper presenting the opposing view. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 11, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashank, T. Hypersexual Disorder: A Comprehensive Review of Conceptualization, Etiology, Assessment and Treatment. Arch. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 7, 054–063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.; Lejoyeux, M. Internet Addiction or Excessive Internet Use. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010, 36, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, T.; Cunnane, E.; Clifford, D.; Davoren, M.P. Defining a Framework for Those with Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder: A Narrative Synthesis. Sex. Health Compulsivity 2023, 30, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, C.; Carlström, C.; Amroussia, N.; Lindrothb, M. Using Twelve-Step Treatment for Sex Addiction and Compulsive Sexual Behaviour (Disorder): A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sex. Health Compulsivity 2024, 31, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlov, M.; Vejmelka, L. Internet addiction: A review of the first twenty years. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, D.P.; Griffiths, M.D. Psychometric Instruments for Problematic Pornography Use: A Systematic Review. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 44, 111–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Strickland, J.C.; Herrmann, E.S.; Dolan, S.B.; Cox, D.J.; Berry, M.S. Sexual discounting: A systematic review of discounting processes and sexual behavior. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 29, 711–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.M.; First, M.B.; Billieux, J.; Cloitre, M.; Briken, P.; Achab, S.; Brewin, C.R.; King, D.L.; Kraus, S.W.; Bryant, R.A. Emerging experience with selected new categories in the ICD-11: Complex PTSD, prolonged grief disorder, gaming disorder, and compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, N.M.; Zajac, K.; Ginley, M.K. Behavioral Addictions as Mental Disorders: To Be or Not To Be? Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 14, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C. Prefrontal Control and Internet Addiction: A Theoretical Model and Review of Neuropsychological and Neuroimaging Findings. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.O.; Teixeira, B.J.; Talib, L.; Scanavino, M.T. (PM-19) Insights into the Pathophysiology of Hypersexuality: A Comprehensive Literature Exploration. J. Sex. Med. 2024, 21, qdae018.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, K.; Hook, R.; Goudriaan, A.E.; Vlies, S.; Fineberg, N.A.; Grant, J.E.; Chamberlain, S.R. Cognitive deficits in problematic internet use: Meta-analysis of 40 studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 215, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, R.F.; Potenza, M.N. A Targeted Review of the Neurobiology and Genetics of Behavioural Addictions: An Emerging Area of Research. Can J. Psychiatry 2013, 58, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, R.F.; Rowland, B.H.P.; Gebru, N.M.; Potenza, M.N. Relationships among impulsive, addictive and sexual tendencies and behaviours: A systematic review of experimental and prospective studies in humans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20180129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberg, B.; Görts-Öberg, K.; Jokinen, J.; Savard, J.; Dhejne, C.; Arver, S.; Fuss, J.; Ingvar, M.; Abé, C. Neural and behavioral correlates of sexual stimuli anticipation point to addiction-like mechanisms in compulsive sexual behavior disorder. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcevic, V.; Khazaal, Y. Relationships between Behavioural Addictions and Psychiatric Disorders: What Is Known and What Is Yet to Be Learned? Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Z.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C. The relationship between adolescent emotion dysregulation and problematic technology use: Systematic review of the empirical literature. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Qin, W.; Liu, Y.; Tian, J. Internet addiction: Neuroimaging findings. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2011, 4, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kürbitz, L.I.; Briken, P. Is Compulsive Sexual Behavior Different in Women Compared to Men? J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcevic, V. Problematic Internet use: A distinct disorder, a manifestation of an underlying psychopathology, or a troublesome behaviour? World Psychiatry 2010, 9, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blycker, G.R.; Potenza, M.N. A mindful model of sexual health: A review and implications of the model for the treatment of individuals with compulsive sexual behavior disorder. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, H.; Rae, C.D.; Steel, A.H.; Winkler, A. Internet Addiction: A Brief Summary of Research and Practice. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2012, 8, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Karila, L.; Billieux, J. Internet Addiction: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Research for the Last Decade. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4026–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedzadeh Dalooyi, S.I.; Aghamohammadian Sharbaaf, H.; Abdekhodaei, M.S.; Ghanaei Chamanabad, A. Biopsychosocial Determinants of Problematic Pornography Use: A Systematic Review. Addict. Health 2023, 15, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboujaoude, E. Problematic Internet use: An overview. World Psychiatry 2010, 9, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginige, P. Internet Addiction Disorder. In Child and Adolescent Mental Health; Maurer, M.H., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Cantus, D. Pornography Addiction: Conceptual and Methodological Approaches in the Post-Pandemic Era. Mini-Review. Glob. J. Addict. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 7, 555718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.A. Problematic Internet Use Among US Youth: A Systematic Review. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2011, 165, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminath, G. Internet addiction disorder: Fact or Fad? Nosing into Nosology. Indian J. Psychiatry 2008, 50, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, J.B.; Perry, S.L. Moral Incongruence and Pornography Use: A Critical Review and Integration. J. Sex. Res. 2019, 56, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, J.B.; Wright, P.J.; Braden, A.L.; Wilt, J.A.; Kraus, S.W. Internet pornography use and sexual motivation: A systematic review and integration. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2019, 43, 117–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, T.; Lyng, T.; Gleason, N.; Finotelli, I.; Coleman, E. Compulsive sexual behavior, religiosity, and spirituality: A systematic review. J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 10, 854–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Online Social Networking and Addiction—A Review of the Psychological Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 3528–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).