Abstract

The present research assessed university student stakeholders’ perceptions of positive outcomes (i.e., appropriateness and benefits of conferencing) and negative outcomes (i.e., endangerment and revictimization of the complainant) associated with restorative justice-based direct conferencing in sexual misconduct cases. Stakeholders received random assignment to a 2 (allegation severity: more vs. less) × 2 (evidence strength: lower vs. higher) between-participant experimental design. More severe allegations and higher evidence strength were associated with lower ratings of appropriateness; allegation severity and evidence strength interacted to affect ratings of benefits; and more severe allegations, but not stronger evidence, were associated with higher ratings of endangerment and revictimization. Belief in the alleged perpetrator’s guilt explained the relationship between evidence strength and ratings of appropriateness, and desire to punish the alleged perpetrator explained the relationship between allegation severity and ratings of appropriateness. Researchers and Title IX coordinators should evaluate and respond to stakeholder sentiment toward direct conferencing.

1. Introduction

Sexual misconduct remains prevalent on university campuses, with a significant minority to a majority of university students reporting experiences of sexual misconduct including unwanted sexual comments and sexual coercion [1]. In the U.S., university Title IX coordinators are empowered to address sexual misconduct allegations to facilitate a learning and living environment free of sexual harassment and violence [2,3]. Methods of addressing sexual misconduct allegations may vary across universities and cases, granted that Title IX coordinators pursue “best practices” for supporting victims and upholding compliance standards set by the federal government [4]. Remedial strategies to support victim wellbeing and to facilitate mutual resolution may include the implementation of restorative justice approaches such as direct conferencing, in which both parties meet to discuss strategies to repair harm [5,6,7,8,9]. Although scholarship has identified potential benefits and dangers of direct conferencing in sexual misconduct cases [10,11,12,13], it remains unclear how university student stakeholders perceive direct conferencing practices. The present research implemented an experimental methodology to examine the effects of allegation severity and evidence strength on stakeholder perceptions of direct conferencing in response to sexual misconduct. The purpose of the current study was to elucidate the circumstances under which stakeholders may perceive direct conferencing practices as more or less productive.

1.1. Retributive and Restorative Approaches to Addressing Wrongdoing

Restorative justice differs from the retributive framework that often characterizes the justice system’s responses to wrongdoing. The retributive framework tends to conceive of wrongdoing as a violation of law or policy that warrants proportional punishment to deter future harm [14]. Retribution involves holding offenders accountable by implementing sanctions via formal court proceedings [15]. This approach tends to prioritize establishing guilt and delivering consequences [16], often with limited involvement from victims or attention to their specific concerns [17].

Restorative justice conceives of wrongdoing as harm to interpersonal and communal relationships beyond rule-breaking [18]. Restorative approaches attempt to repair harm by facilitating communication between victims, offenders, and community members [19,20]. Involved parties address the root causes of offending, discuss its effects, and decide how to respond collectively [21]. Direct conferencing represents one restorative approach to promote mutual understanding and healing, providing participants with an opportunity to interact with one another and to determine their own outcomes rather than having consequences imposed by courts [22,23,24]. Despite the strengths of this approach, its appropriateness may vary depending on contextual factors such as the severity of the allegation and the strength of supporting evidence.

1.2. Title IX and Sexual Misconduct

Title IX coordinators, government officials, and university administrators continue to seek strategies to reduce rates of sexual misconduct on university campuses. Title IX guidance is instrumental to this process because it governs how universities adjudicate sexual misconduct allegations. However, guidance has varied over the last number of years due to policy debates and personnel changes within the U.S. federal government.

Published by the U.S. Department of Education in 2011, the oft-cited “dear colleague” letter addressed universities receiving federal funding to emphasize the importance of effective sexual misconduct response strategies and adherence to Title IX guidelines [25]. To curtail unacceptably high rates of sexual misconduct on university campuses, the letter clarified enforcement standards including a lower standard of proof to find the accused guilty of sexual misconduct allegations and the ability for complainants to appeal not-guilty verdicts. Intended to achieve justice for victims of sexual misconduct, these standards simultaneously made it more difficult for the wrongfully accused (approximately 6% of cases [26]) to assert their innocence [27].

Debates over interpretations of Title IX as articulated in the 2011 “dear colleague” letter led to subsequent guidance in 2014 [28]. By 2017, a new federal government administration rescinded the 2011 and 2014 letters [29]. The 2017 changes to the interpretation of Title IX allowed universities to reinstate higher standards of proof and deny complainants the right to appeal, effectively reversing the 2011 guidance. Multiple state attorneys general filed legal challenges to the Trump-era regulations [30]. Volatility regarding Title IX interpretations on university campuses continued into 2022 when the Biden administration again altered Title IX regulations to reverse aspects of the previous administration’s guidance, including returning to a lower standard of proof [3]. Recent volatility in Title IX interpretations can threaten the ability of all parties to achieve justice. It is necessary for those involved in Title IX sexual misconduct complaints to perceive that the process of adjudication is fair and transparent to foster a sense of legitimacy and trust in its resolution [31]. It may be beneficial for university Title IX coordinators to adopt an approach to repairing harm following claims of sexual misconduct that can remain consistent despite federal administrative changes.

1.3. Restorative Justice and Title IX

Restorative justice approaches aim to repair harm and maintain harmonious relationships between victims, offenders, and the community [7,16,32]. Approaches to restorative justice allow victims to be heard and understood by offenders and other stakeholders. In addition, restorative justice approaches encourage offenders to learn from their mistakes through the process of identifying and addressing the ultimate causes of offending [33]. One approach to restorative justice involves organizing a direct conference between victim and offender, facilitated and overseen by a Title IX coordinators, and with permission from all parties [5,6,7,10,13].

Title IX coordinators may encourage restorative justice and direct conferencing as means of repairing harm following wrongdoing in sexual misconduct cases [8]. This approach can facilitate justice for victims and ensure safety for the broader campus community by addressing the causes of offending. Moreover, direct conferencing offers a strategy for conflict resolution that can operate consistently on university campuses despite changing standards of proof and varying appeals processes that result from fluctuating interpretations of Title IX.

Researchers and practitioners have proposed conferencing programs to address sexual misconduct using a restorative justice approach [11,12,34]. Implementation of the RESTORE conferencing program, piloted for community sexual assault cases rather than among a student population, demonstrated that participants were generally satisfied with conferencing and would recommend it as a means of conflict resolution [34]. However, there were some concerns for negative outcomes associated with conferencing, especially revictimization [34]. The Report on Promoting Restorative Initiatives for Sexual Misconduct (PRISM), which provides recommendations for university campuses, encourages communication between victims and offenders and promotes opportunities to achieve justice via mutual understanding in a safe environment [35]. Others have also proposed the application of restorative justice principles to address sexual misconduct allegations, recommending that institutions invest in facilitator training and education regarding restorative justice [11]. These authors call for empirical investigations of restorative justice approaches to guide implementation on university campuses [11]. Despite the potential for direct conferencing to offer an additional avenue for repairing harm following sexual misconduct, it is possible that such a conference, even when facilitated by Title IX coordinators with permission from both parties, could lead to adverse consequences for the victim. For example, complainants may feel revictimized following exposure to and communication with the accused, and they may express concern for physical endangerment following the conference [10,13]. It is pertinent to examine stakeholders’ perceptions of direct conferencing using an experimental approach.

1.4. Measuring Stakeholder Perceptions

It is imperative for university Title IX offices to understand and account for stakeholder perceptions when determining whether to utilize direct conferencing as a method to repair harm. Community sentiment refers to stakeholders’ collective attitudes toward policies and procedures that affect their lives [36]. The term community is defined broadly in the psycho-legal context. A community may include policymakers, law enforcement officers, legal decision-makers such as judges and jurors, victims, defendants, family members, or others to whom a particular policy applies [36]. The present research examined a community of university students who have stake in campus responses to allegations of wrongdoing. Measuring community sentiment is essential for designing and implementing policies and procedures that best attend to stakeholders’ needs and concerns. Researchers can measure community sentiment through a variety of means, including evaluating social media posts, collecting data via opinion polls, or conducting experimental research. The present study utilized an experimental approach to systematically examine how stakeholder perceptions of direct conferencing vary as a function of allegation severity and evidence strength, as these factors may differ across Title IX complaints. Such experimental research can offer insights to Title IX coordinators as they determine how best to approach achieving justice after an allegation of sexual misconduct.

Although prior work has offered guidance for implementing restorative justice approaches such as direct conferencing to address sexual misconduct complaints [11,35], it is yet unclear how university student stakeholders perceive such strategies [34]. Experimental research can provide a systematic analysis of community sentiment by varying common factors present in Title IX complaints and assessing stakeholders’ subsequent perceptions. An experimental approach helps to isolate effects of relevant variables and provide concrete, evidence-based recommendations for addressing allegations of sexual misconduct. Before implementing direct conferencing to resolve sexual misconduct allegations, Title IX coordinators may wish to consider whether stakeholders agree that direct conferencing is appropriate in such cases and beneficial to victims, perpetrators, and the university community at large. Moreover, it is pertinent to understand whether stakeholders foresee negative outcomes associated with direct conferencing such as risks to the victim (e.g., psychological revictimization, physical endangerment) [10,13].

Stakeholders’ perceptions of positive outcomes (e.g., appropriateness of the conference, benefits to those involved) and negative outcomes (e.g., psychological revictimization, physical endangerment) may vary according to the details of the case. Stakeholders may hold more positive attitudes toward direct conferencing in cases in which allegations are less severe or in which evidence indicating guilt is relatively weak. In contrast, stakeholders may hold more negative attitudes toward direct conferencing in cases in which allegations are more severe or in which evidence indicating guilt is relatively strong. An assessment of stakeholder perceptions may inform Title IX coordinators’ strategic employment of restorative justice approaches under circumstances that stakeholders deem appropriate.

2. Method

Stakeholder perceptions of positive and negative outcomes associated with direct conferencing in sexual misconduct cases may depend on features of the case. To examine community sentiment toward direct conferencing as an approach to repairing harm following a sexual misconduct allegation, the present study utilized a 2 (allegation severity: more vs. less) × 2 (evidence strength: lower vs. higher) between-participant experimental design. Following random assignment to one of the four experimental conditions, university student stakeholders reviewed case facts and rated the extent to which they believed direct conferencing would be appropriate and beneficial (i.e., positive outcomes) and subject the victim to potential revictimization and endangerment (i.e., negative outcomes).

First, I hypothesized main effects of allegation severity and evidence strength, such that stakeholders would report more favorable sentiment toward direct conferencing when the allegation was less (vs. more) severe and when the evidence was weaker (vs. stronger). Second, I hypothesized that these main effects would be qualified by a two-way interaction such that when the allegation was less severe, stakeholders would report relatively favorable sentiment toward direct conferencing regardless of evidence strength. However, when the allegation was more severe, stakeholders would report significantly less favorable sentiments when evidence was stronger versus weaker. Third, I hypothesized that guilt judgments would mediate a negative effect of evidence strength on ratings of the appropriateness of direct conferencing. Fourth, I hypothesized that the desire to punish the alleged perpetrator would mediate a negative effect of allegation severity on ratings of the appropriateness of direct conferencing. This research was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at a university in the southern U.S. under the approval code LIV072022A.

2.1. Participants

Participants were 299 university students who completed the study in exchange for course credit (Mage = 20.01 years, SD = 3.54). Most participants were women (75.25%). A plurality of participants identified as White (42.14%) followed by Hispanic or Latino/a (41.47%), Black or African American (8.03%), Asian (2.68), and other/mixed race (5.68%). University students were the ideal population among whom to test the present hypotheses because they are often stakeholders in cases of sexual misconduct on university campuses [37].

2.2. Materials

The Qualtrics survey software platform randomly assigned participants to one of four experimental conditions. Participants read case facts that varied by experimental condition, responded to dependent measures, and provided their demographic information. All dependent measures used 7-point Likert-type scales. Dependent measures demonstrated face validity to (1) assess constructs relevant to restorative justice including allowing victims to be understood and allowing offenders to learn from mistakes to prevent future harm [16,33,38], and (2) assess potential risks associated with direct conferencing including psychological and physical danger for the victim [10,13]. A separate pilot study among 88 university students demonstrated the internal consistency of each measure prior to inclusion in the present study (Cronbach’s αs > 0.70; McDonald’s ωs > 0.72). All reliability measures reported below reflect the present dataset (N = 299), which did not include pilot data.

2.2.1. Case Facts

The description of case facts consisted of approximately 200 words (see Appendix A for the vignettes). Participants received background information regarding the role of campus police departments and Title IX offices to respond to reports of sexual misconduct on university campuses. Participants learned that direct conferencing is one option in such cases. Instructions informed participants that they would read about a specific allegation of sexual misconduct and indicate whether they believed direct conferencing was appropriate in that case.

Each vignette described a case in which a female student accused a male student of sexual misconduct. The evidence against the accused and the allegation varied depending on experimental condition. To manipulate evidence strength, participants read that the university’s investigation either (1) yielded audio-video surveillance footage supporting the allegation (evidence strength: higher) or (2) yielded no evidence (evidence strength: lower). To manipulate allegation severity, participants read that the complainant alleged either (1) forcible touching under her clothing (allegation severity: more) or (2) unwanted sexual comments (allegation severity: less). Although both allegations represent harmful acts of sexual misconduct, the more severe allegation was operationalized as unwanted touching because such behavior is typically associated with more severe sanctions [3].

After reading the case facts vignette, participants received information that the goal of a direct conference was to deal with the consequences of the alleged sexual misconduct and decide how best to repair the alleged harm. These goals align with those of the restorative justice approach to jurisprudence [16,32,38]. Participants advanced to the dependent measures after they responded accurately to comprehension check items, which assessed participants’ recollection of the specific allegation and the supporting evidence described in the case facts vignette. Participants who provided inaccurate responses to the comprehension check items received the opportunity to reexamine the case facts and instructions until they achieved comprehension.

2.2.2. Manipulation Checks

Two scales assessed the effectiveness of the experimental manipulations to alter stakeholders’ perceptions of the evidence strength and allegation severity described in the case facts vignette. Each scale consisted of three items and demonstrated adequate reliability for inclusion in inferential analyses (Cronbach’s αs > 0.91, McDonald’s ωs > 0.91).

2.2.3. Measures of Guilt and Punishment

Measures of belief in the alleged perpetrator’s guilt and the desire to punish the alleged perpetrator served as mediating variables in mediation analyses. To assess these constructs, participants responded to two five-item scales. First, the measure of guilt included items such as, “I think he did what she alleged” and “He may very well be innocent” (reverse coded). The scale displayed adequate reliability for inclusion in inferential analyses (Cronbach’s α = 0.92, McDonald’s ω = 0.92). Second, the measure of punishment included items such as “He should be punished severely for the alleged offense” and “He should receive a very lenient (minimal) punishment for the alleged offense” (reverse coded). The scale displayed adequate reliability for inclusion in inferential analyses (Cronbach’s α = 0.75, McDonald’s ω = 0.78).

2.2.4. Ratings of Positive Outcomes of Conferencing

Positive perceptions of direct conferencing included beliefs that the conference was appropriate and that the conference would benefit both parties. The seven-item measure of appropriateness included items such as, “A conference between the parties is a good idea” and “A conference between the parties seems inappropriate” (reverse coded). The scale displayed adequate reliability for inclusion in inferential analyses (Cronbach’s α = 0.97, McDonald’s ω = 0.97). The seven-item measure of benefits included items such as, “The conference will help to deal with the consequences of the alleged misconduct” and “The conference can effectively repair the alleged harm.” The scale displayed adequate reliability for inclusion in inferential analyses (Cronbach’s α = 0.86, McDonald’s ω = 0.86).

2.2.5. Ratings of Negative Outcomes of Conferencing

Negative perceptions of direct conferencing included concerns that the conference would bring psychological trauma (i.e., revictimization) or physical harm (i.e., endangerment) to the complainant. The five-item measure of revictimization included items such as, “She will be revictimized by the conference with him” and “She is at risk of damaging her mental health if she engages in the conference.” The scale displayed adequate reliability for inclusion in inferential analyses (Cronbach’s α = 0.84, McDonald’s ω = 0.85). The five-item measure of endangerment included items such as, “The conference puts her at risk of physical danger” and “He might retaliate against her after the conference.” The scale displayed adequate reliability for inclusion in inferential analyses (Cronbach’s α = 0.83, McDonald’s ω = 0.83).

2.3. Procedure

Participants voluntarily enrolled in the study via a university research participation website. The website redirected participants to Qualtrics and presented an informed consent document containing a description of the nature of the study as well as resources for reporting sexual misconduct. After receiving random assignment to one of the four experimental conditions and responding to the dependent measures, participants provided their demographic information, received a debriefing statement, and were redirected to the university’s research participation website to redeem their course credit. The mean study completion time was approximately 14 minutes.

3. Results

Analyses to test hypotheses included t-test, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and mediation models [39]. All continuous variable distributions were normal with skewness and kurtosis within the range of ±2 requiring no transformation [40]. See Table 1 and Table 2 for means and standard deviations of each dependent variable separated by condition. Data are available via the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/bns7j/?view_only=f84407c35ba643a6825a85d83311dab3; accessed on 17 April 2024).

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of dependent variables separated by evidence strength condition (low vs. high). ns = p > 0.05.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of dependent variables separated by allegation severity condition (less vs. more). ns = p > 0.05.

A sensitivity analysis conducted in G*Power (Version 3.1) [41] for two-way ANOVA demonstrated that the smallest reliable effect statistical analyses could detect was Cohen’s f = 0.19 with a critical Fisher’s F-value of 3.87, given an alpha error rate of 0.05 and desired statistical power of 0.90. The observed Cohen’s f for the largest statistical model was 0.25, calculated by converting ηp2 to Cohen’s f. Moreover, observed Fisher’s F-values exceeded the critical value. Thus, the present study had adequate sensitivity to test the current hypotheses.

3.1. Manipulation Checks

Two independent samples t-tests examined the efficacy of the experimental manipulations. First, participants assigned to the high-evidence-strength condition (M = 5.96, SD = 1.05) reported that the evidence against the alleged perpetrator was significantly stronger compared to participants assigned to the low-evidence-strength condition (M = 2.02, SD = 1.07), t(297) = −32.26, p < 0.001, d = -3.73. Second, participants assigned to the high-allegation-severity condition (M = 6.16, SD = 0.95) reported that the allegation against the alleged perpetrator was significantly more severe compared to participants assigned to the low-allegation-severity condition (M = 5.01, SD = 1.36), Welch’s t(269.23) = −8.50, p < 0.001, d = −0.98. These findings indicated that both manipulations were effective. Thus, the experimental conditions could be used as independent variables in subsequent analyses.

3.2. Effects of Case Facts on Positive Outcomes of Conferencing

Two two-way ANOVAs examined the main effects and interactions of evidence strength and allegation severity on the positive outcomes of conferencing: namely, ratings of the appropriateness and benefits of the conference, respectively.

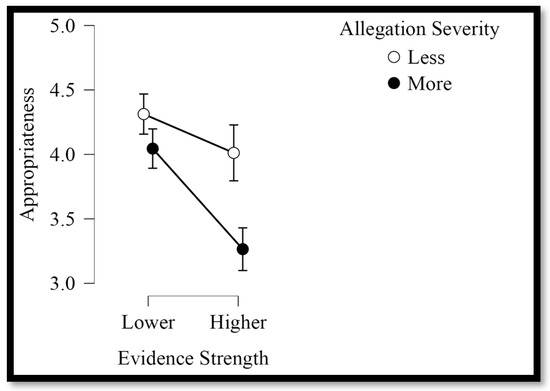

The first ANOVA testing the effects of the independent variables on ratings of appropriateness of conferencing revealed two main effects (Figure 1). There was a main effect of evidence strength, F(1,295) = 9.69, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.03, such that stakeholders rated conferencing as more appropriate when evidence strength was low (M = 4.18, SD = 1.35) versus high (M = 3.63, SD = 1.68). There was also a main effect of allegation severity, F(1,295) = 8.54, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.03, such that stakeholders rated conferencing as more appropriate when the allegation was less severe (M = 4.17, SD = 1.62) versus more severe (M = 3.65, SD = 1.42). The interaction between evidence strength and allegation severity on ratings of appropriateness of conferencing was nonsignificant (p = 0.17).

Figure 1.

Bars represent standard error around the mean.

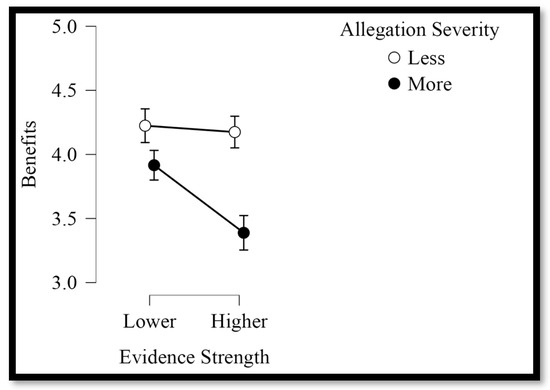

The second ANOVA testing the effects of the independent variables on ratings of the benefits of conferencing revealed two main effects (Figure 2). There was a main effect of evidence strength, F(1,295) = 5.16, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.02, such that stakeholders rated conferencing as more beneficial when evidence strength was low (M = 4.08, SD = 1.09) versus high (M = 3.77, SD = 1.17). There was also a main effect of allegation severity, F(1,295) = 18.58, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06, such that stakeholders rated conferencing as more beneficial when the allegation was less severe (M = 4.20, SD = 1.11) versus more severe (M = 3.65, SD = 1.11).

Figure 2.

Bars represent standard error around the mean.

These main effects were qualified by a trending two-way interaction, F(1,295) = 3.54, p = 0.06, ηp2 = 0.01. When the allegation was less severe, ratings of benefits did not vary as a function of stronger evidence (M = 4.18, SD = 1.05) versus weaker evidence (M = 4.22, SD = 1.17; p > 0.05). However, when the allegation was more severe, participants rated conferencing as significantly less beneficial when the evidence was stronger (M = 3.39, SD = 1.17) versus weaker (M = 3.92, SD = 0.99; p = 0.004). This finding indicated that stakeholders perceived direct conferencing to be less beneficial in cases that involved a severe allegation supported by strong evidence.

3.3. Effects of Case Facts on Negative Outcomes of Conferencing

Two two-way ANOVAs examined the main effects and interactions of evidence strength and allegation severity on the negative outcomes of conferencing: namely, ratings of the extent to which the conference might endanger or revictimize the complainant, respectively.

The first ANOVA testing the effects of the independent variables on ratings of endangerment revealed a main effect of allegation severity, F(1,295) = 7.46, p = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.03, such that stakeholders rated conferencing as more likely to endanger the complainant when the allegations were more severe (M = 4.32, SD = 1.11) versus less severe (M = 3.95, SD = 1.16). There were no other significant main effects or interactions.

The second ANOVA testing the effects of the independent variables on ratings of revictimization also revealed a main effect of allegation severity, F(1,295) = 5.57, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.02, such that stakeholders rated conferencing as more likely to revictimize the complainant when the allegations were more severe (M = 4.58, SD = 1.10) versus less severe (M = 4.25, SD = 1.23). There were no other significant main effects or interactions.

3.4. Explaining the Relationships Between Case Facts and Appropriateness of Conferencing

Given that evidence strength and allegation severity affected ratings of the appropriateness of conferencing, it was pertinent to examine variables that could explain these relationships. Mediation analyses tested hypotheses that stakeholders’ belief in the alleged perpetrator’s guilt would explain the effect of evidence strength on appropriateness ratings, and that stakeholders’ desire to punish the alleged perpetrator would explain the effect of allegation severity on appropriateness ratings. Bootstrapping analyses [42,43] tested each mediation model using the jaspSem package (Version 0.19.3) [39].

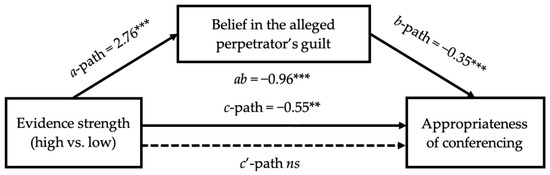

The first mediation analysis examined whether belief in the alleged perpetrator’s guilt explained the effect of evidence strength on ratings of the appropriateness of the conference. Figure 3 depicts the model and path coefficients. The total effect (c-path) of evidence strength on appropriateness ratings was significant, b = −0.55, 95% CI [−0.90, −0.21], p = 0.002. The indirect effect (ab-path) through guilt ratings (i.e., the mediator) was significant, b = −0.96, 95% CI [−1.43, −0.49], indicating that the mediator provided an explanatory pathway linking the independent and dependent variables (p < 0.001). When accounting for the mediator, the direct effect (c’-path) of evidence strength on ratings of appropriateness was no longer significantly different from zero, b = 0.41, 95% CI [−0.17, 0.98], p = 0.16, indicating that guilt ratings explained the relationship. Stronger (vs. weaker) evidence increased perceptions of the alleged perpetrator’s guilt (a-path; b = 2.76, z = 23.98, p < 0.001), which was associated in turn with decreased ratings of appropriateness of the conference (b-path; b = −0.35, z = −4.05, p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Mediation model depicting the relationship between evidence strength (IV) and appropriateness of conferencing (DV) through belief in perpetrator guilt (M). *** = p < 0.001, ** = p < 0.01, ns = p > 0.05.

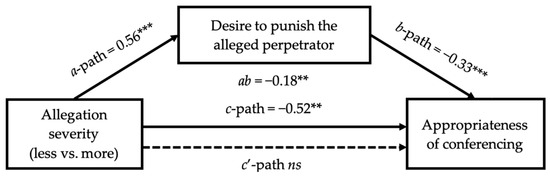

The second mediation analysis examined whether the desire to punish the alleged perpetrator explained the effect of allegation severity on ratings of the appropriateness of the conference. Figure 4 depicts the model and path coefficients. The total effect (c-path) of allegation severity on appropriateness ratings was significant, b = −0.52, 95% CI [−0.86, −0.18], p = 0.003. The indirect effect (ab-path) through punishment ratings (i.e., the mediator) was significant, b = −0.18, 95% CI [−0.30, −0.07], indicating that the mediator provided an explanatory pathway linking the independent and dependent variables (p = 0.002). When accounting for the mediator, the direct effect (c’-path) of allegation severity on ratings of appropriateness was no longer significantly different from zero, b = −0.34, 95% CI [−0.68, 0.01], p = 0.06, indicating that punishment ratings explained the relationship. More (vs. less) severe allegations increased stakeholders’ desire to punish the offender (a-path; b = 0.56, z = 4.43, p < 0.001), which was associated in turn with decreased ratings of the appropriateness of the conference (b-path; b = −0.33, z = −4.18, p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Mediation model depicting the relationship between allegation severity (IV) and appropriateness of conferencing (DV) through desire to punish the perpetrator (M). *** = p < 0.001, ** = p < 0.01, ns = p > 0.05.

3.5. Summary of Results

ANOVA examined main effects and interactions among the independent variables (i.e., evidence strength and allegation severity) and the dependent variables (i.e., positive and negative outcomes). Stakeholders tended to rate direct conferencing as more appropriate and more beneficial when evidence strength was low and when the allegation was less severe. Regarding ratings of appropriateness, both low evidence strength and less severe allegations led independently to higher ratings (Figure 1). Regarding ratings of benefits, similar main effects emerged and were qualified by a trending two-way interaction: for less severe allegations, benefits ratings did not vary by evidence strength; for more severe allegations, benefits ratings were lower in the presence of stronger evidence (Figure 2). Regarding negative outcomes, participants rated direct conferencing as more likely to endanger or revictimize the complainant when allegations were more severe.

Mediation analysis revealed variables that explained these effects. Stakeholders’ belief in the alleged perpetrator’s guilt explained the relationship between evidence strength and ratings of appropriateness. Stronger evidence increased guilt ratings, which in turn decreased ratings of appropriateness of direct conferencing (Figure 3). Similarly, stakeholders’ desire to punish the alleged perpetrator explained the relationship between allegation severity and ratings of appropriateness. More severe allegations increased the desire to punish, which in turn decreased ratings of appropriateness of direct conferencing (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The current study examined stakeholder perceptions of direct conferencing as a strategy to repair harm following campus sexual misconduct allegations. Given recent vacillation in the application of federal Title IX policy, it is pertinent to explore alternative approaches to addressing sexual misconduct allegations. Restorative justice principles that aim to maintain harmonious relationships between victims, offenders, and the university community might offer effective and consistent strategies, such as direct conferencing between parties [5,13,16,34]. Despite efforts to develop direct conferencing strategies for use on university campuses, it remained unknown how university student stakeholders would perceive the potential positive and negative outcomes of direct conferencing. The present research implemented an experimental paradigm to examine community sentiment. Findings revealed that factors such as allegation severity and evidence strength affected stakeholders’ perceptions of the positive and negative outcomes of direct conferencing in sexual misconduct cases.

4.1. Stakeholder Perceptions of Direct Conferencing

Stakeholders tended to perceive direct conferencing to be a generally appropriate and beneficial strategy for repairing harm following an allegation of sexual misconduct. Ratings of appropriateness and benefits were near the scale midpoint (see Table 1 and Table 2), suggesting that stakeholders may identify positive outcomes associated with direct conferencing under certain circumstances.

Interactions between the independent variables helped to reveal the circumstances under which stakeholders may endorse direct conferencing in sexual misconduct cases. When allegations are less severe, stakeholders tended to endorse direct conferencing across levels of evidence strength. This finding suggests that stakeholders may believe that less severe allegations can be addressed adequately during a direct conference that promotes mutual understanding and a plan to repair harm. However, when allegations were more severe, endorsement of direct conferencing depended on the strength of evidence against the alleged perpetrator. More severe allegations coupled with stronger evidence of the perpetrator’s guilt led stakeholders to rate direct conferencing as less appropriate and less beneficial. In such cases, stakeholders might prefer a more punitive or retributive approach to achieving justice [16]. Direct conferencing may be advisable when allegations are less severe or when evidence indicating perpetrator guilt is weaker.

Mediation analysis explored mechanisms underlying the observed effects. More severe allegations led to increased desire to punish the alleged perpetrator, which in turn was associated with reduced ratings of appropriateness of conferencing. Stakeholders may believe that direct conferencing is relatively inappropriate when the accused is likely guilty, yet stakeholders may be more amenable to direct conferencing when guilt is less apparent due to weaker evidence. Stronger evidence led to increased belief that the alleged perpetrator was guilty, which in turn was also associated with reduced ratings of appropriateness of conferencing. Stakeholders may believe that direct conferencing is relatively inappropriate as a form of punishment for the perpetrator despite its potential benefits to restore harmonious relations between the victim, the perpetrator, and the community. Stakeholders might prefer to punish those accused of severe offenses rather than, or in addition to, offering restoration.

Stakeholders expressed reservations about physical endangerment and psychological revictimization for the complainant due to direct conferencing. Ratings of negative outcomes due to direct conferencing were just above the scale midpoint (see Table 1 and Table 2), suggesting that Title IX coordinators should consider community sentiment when determining whether to implement a direct conferencing strategy. Stakeholders rated negative outcomes significantly higher when allegations were more severe versus less severe, across levels of evidence strength. University students may believe direct conferencing can cause additional harm to victims of more severe offenses. Title IX coordinators can apply these findings to serve stakeholders by offering direct conferencing as an approach to repairing harm following less severe allegations, and by pursuing alternative conflict resolution strategies (e.g., disciplinary approaches, referrals to local police) in the context of more severe allegations. Recognizing stakeholders’ reservations about negative outcomes helps to identify the limitations of direct conferencing.

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

The current study is not without limitations that future research may address. First, although the present findings can inform psychology-law research and Title IX investigations, these data report on the perceptions of one sample of university student stakeholders. Present results require replication among additional student samples to demonstrate the extent to which perceptions of direct conferencing in Title IX investigations generalize to additional university campus communities. Whereas the current sample rated direct conferencing as relatively less appropriate and less beneficial in the context of severe allegations and strong supporting evidence, other campus communities might endorse direct conferencing as an approach under additional circumstances.

Second, most participants who completed the present study were women, which could indicate a gender-based self-selection bias present in the current data. Women often comprise the majority in samples of university students [44,45], in part because women enroll in postsecondary education at higher rates compared to men [46]. This gender imbalance is especially prominent among students enrolled in psychology programs, approximately 70% of whom are women [47,48]. These figures align with the present sample, suggesting that self-selection bias likely had minimal influence on the present results. Future research could recruit a larger quota of men and focus analyses on any gender differences in sentiments toward direct conferencing that may emerge. In addition to examining potential gender differences, future research could explore how prior experience as a victim or perpetrator of sexual violence might influence attitudes toward restorative approaches. Persons with a history of sexual violence may value the time efficiency and closure often provided by conferencing [15].

Third, the present research contrasted more versus less severe allegations and stronger versus weaker evidence to examine whether these conceptually relevant variables affected stakeholder perceptions. Given the relevance of these factors as suggested by the present findings, future research should employ alternative forms of allegations (e.g., stalking, sharing of unsolicited nude photos) and evidence (e.g., witness statements, suspect admissions) to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the conditions under which stakeholders endorse direct conferencing as a strategy to repair harm.

Fourth, this research examined perceptions of direct conferencing exclusively. Future research may compare direct conferencing to alterative restorative justice approaches (e.g., victim impact panels, circles of accountability) [49,50,51] as well as to more retributive approaches to quantify stakeholder preferences for various strategies to address wrongdoing. Additional scholarship is needed to examine how factors such as evidence strength and allegation severity influence endorsement of restorative versus retributive responses. Moreover, future investigations should compare stakeholder sentiment across cultures as the implementation and prevalence of restorative approaches can vary internationally [52,53,54].

Fifth, the present research methodology was experimental and quantitative. This design was appropriate for examining cause-effect relationships between variables of interest and documenting the size of these effects. Future research may wish to complement the present findings by conducting qualitative analyses that capture the expressed attitudes of stakeholders broadly and perhaps victims specifically toward direct conferencing. Qualitative methods can facilitate a wider range of participant responses that may guide the development of future quantitative studies.

Finally, the present study assessed a non-exhaustive list of positive outcomes (i.e., appropriateness, benefits) and negative outcomes (i.e., revictimization, endangerment) that could be associated with direct conferencing [10,13]. Future research should examine stakeholder perceptions of additional considerations such as fairness, thoroughness, power imbalances, and resource limitations. These variables and others should inform evidence-based responses to sexual misconduct allegations.

5. Conclusions

Controversy and administrative changes have led to volatility in the interpretation and application of Title IX on university campuses. Approaches to repairing harm using restorative justice strategies, such as direct conferencing between parties involved in an allegation of sexual misconduct, can offer an alternative method of conflict resolution that remains stable over time and across campuses. Title IX coordinators should consider the perceptions of their university student stakeholders to determine whether to recommend direct conferencing in response to allegations of sexual misconduct. The present research suggested that stakeholders consider allegation severity and evidence strength in weighing the positive outcomes (e.g., appropriateness, benefits) versus the negative outcomes (e.g., revictimization, endangerment) of direct conferencing. Future research should employ a variety of research methods, including experimental methods as in the current study, to measure community sentiment.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Angelo State University (protocol code LIV072022A, approved on 14 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/bns7j/?view_only=f84407c35ba643a6825a85d83311dab3, accessed on 17 April 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The vignettes below manipulated allegation severity (more vs. less) and evidence strength (lower vs. higher). The headings describe the experimental condition, followed by the stimuli participants received. Participants received one of the four vignettes based on random assignment.

- Instructions:

Students at universities across the U.S. report incidents to their campus police departments and to their Title IX offices, the latter of which specifically handles issues of sexual harassment.

Title IX officers have the option to invite the accuser and the accused to a face-to-face conference to discuss the allegation. Below, you will read about a specific allegation. Then, we will ask you some questions about whether you feel a face-to-face conference is appropriate and beneficial in this case.

With Brianna’s permission, university administration invited both Brianna and Christopher to a conference mediated by the university’s sexual misconduct officer. The purpose of the conference was threefold:

- (1)

- for both Brianna and Christopher to discuss the allegations face-to-face in the presence of university administration;

- (2)

- to deal with the consequences of Christopher’s alleged sexual misconduct; and

- (3)

- for Brianna and Christopher to decide how best to repair the alleged harm.

- Allegation Severity: More; Evidence Strength: Higher

Brianna is a student at the university who recently reported to administration that she was a victim of sexual misconduct. Brianna accused another student, Christopher, of forcibly touching her under her clothes on university property.

University administration investigated the accusation. They contacted potential witnesses and assessed campus audio-video surveillance footage.

The university’s investigation yielded strong evidence of the alleged misconduct in the form of audio-video surveillance footage of Christopher forcibly touching Brianna under her clothes on university property. That is, there was audio-video proof to substantiate Brianna’s allegation that Christopher forcibly touched Brianna under her clothes on university property.

- Allegation Severity: Less; Evidence Strength: Higher

Brianna is a student at the university who recently reported to administration that she was a victim of sexual misconduct. Brianna accused another student, Christopher, of making unwanted sexual comments to her on university property.

University administration investigated the accusation. They contacted potential witnesses and assessed campus audio-video surveillance footage.

The university’s investigation yielded strong evidence of the alleged misconduct in the form of audio-video surveillance footage of Christopher making unwanted sexual comments to her on university property. That is, there was audio-video proof to substantiate Brianna’s allegation that Christopher made unwanted sexual comments to her on university property.

- Allegation Severity: More; Evidence Strength: Lower

Brianna is a student at the university who recently reported to administration that she was a victim of sexual misconduct. Brianna accused another student, Christopher, of forcibly touching her under her clothes on university property.

University administration investigated the accusation. They contacted potential witnesses and assessed campus audio-video surveillance footage.

The university’s investigation yielded no evidence of the alleged misconduct. That is, there was no proof to substantiate Brianna’s allegation that Christopher forcibly touched Brianna under her clothes on university property.

- Allegation Severity: Less; Evidence Strength: Lower

Brianna is a student at the university who recently reported to administration that she was a victim of sexual misconduct. Brianna accused another student, Christopher, of making unwanted sexual comments to her on university property.

University administration investigated the accusation. They contacted potential witnesses and assessed campus audio-video surveillance footage.

The university’s investigation yielded no evidence of the alleged misconduct. That is, there was no proof to substantiate Brianna’s allegation that Christopher made unwanted sexual comments to her on university property.

References

- Klein, L.B.; Martin, S.L. Sexual Harassment of College and University Students: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 22, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Code. 20 U.S. Code § 1681—Sex. Available online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/20/1681 (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- U.S. Department of Education. Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Sex in Education Programs or Activities Receiving Federal Financial Assistance. 2022. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-07-12/pdf/2022-13734.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- U.S. Department of Education. Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Sex in Education Programs or Activities Receiving Federal Financial Assistance. 2020. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-05-19/pdf/2020-10512.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Koss, M.P.; Wilgus, J.K.; Williamsen, K.M. Campus Sexual Misconduct: Restorative Justice Approaches to Enhance Compliance with Title IX Guidance. Trauma Violence Abus. 2014, 15, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangan, K. Why More Colleges are Trying Restorative Justice in Sex-Assault Cases. The Chronical of Higher Education. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-more-colleges-are-trying-restorative-justice-in-sex-assault-cases/ (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Sherman, L.W.; Strang, H. Restorative Justice as Evidence-Based Sentencing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education. Summary of Major Provisions of the Department of Education’s Title IX Final Rule. Available online: https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/titleix-summary.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Vail, K. The Failings of Title IX for Survivors of Sexual Violence: Utilizing Restorative Justice on College Campuses. Wash. Law Rev. 2019, 94, 2085–2118. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, S.; Maskaly, J.; Kirkner, A.; Lorenz, K. Enhancing Title IX Due Process Standards in Campus Sexual Assault Adjudication: Considering the Roles of Distributive, Procedural, and Restorative Justice. J. Sch. Violence 2017, 16, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.; Hetzel-Riggin, M.D. Campus Sexual Violence and Title IX: What Is the Role of Restorative Justice Now? Fem. Criminol. 2022, 17, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, D.R. Restorative Justice and Responsive Regulation in Higher Education. In Restorative and Responsive Human Services; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, C.; Westmarland, N.; Godden, N. ‘I Just Wanted Him to Hear Me’: Sexual Violence and the Possibilities of Restorative Justice. J. Law Soc. 2012, 39, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, J.M. Is Revenge about Retributive Justice, Deterring Harm, or Both? Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2017, 11, e12296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, K. Restorative Justice and Sexual Assault: An Archival Study of Court and Conference Cases. Br. J. Criminol. 2005, 46, 334–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; Okimoto, T.G.; Feather, N.T.; Platow, M.J. Retributive and Restorative Justice. Law Hum. Behav. 2008, 32, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, K. Revisiting the Relationship between Retributive and Restorative Justice. In Restorative Justice: From Philosophy to Practice; Ashgate Publishing Company: Surrey, UK, 2001; pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, J. Encourage Restorative Justice. Criminol. Public Policy 2007, 6, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menkel-Meadow, C. Restorative Justice: What Is It and Does It Work? Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2007, 3, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulnier, A.; Sivasubramaniam, D. Restorative Justice: Reflections and the Retributive Impulse. In Advances in Psychology and Law; Miller, M.K., Bornstein, B.H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 3, pp. 177–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, T.F. The Evolution of Restorative Justice in Britain. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 1996, 4, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, S.P. Restorative Justice, Punishment, and Atonement. Utah Law Rev. 2003, 1, 303–317. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrielides, T. Domestic Violence and Power Abuse Within the Family: The Restorative Justice Approach. In Violence in Families; Sturmey, P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, L.W.; Strang, H.; Angel, C.; Woods, D.; Barnes, G.C.; Bennett, S.; Inkpen, N. Effects of Face-to-Face Restorative Justice on Victims of Crime in Four Randomized, Controlled Trials. J. Exp. Criminol. 2005, 1, 367–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education. Dear Colleague Letter: Sexual Violence Background, Summary, and Fast Facts. 2011. Available online: https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/dcl-factsheet-201104.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Lisak, D.; Gardinier, L.; Nicksa, S.C.; Cote, A.M. False Allegations of Sexual Assault: An Analysis of Ten Years of Reported Cases. Violence Against Women 2010, 16, 1318–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creeley, W. Why the Office for Civil Rights’ April ‘Dear Colleague Letter’ Was 2011’s Biggest FIRE Fight. Available online: https://www.thefire.org/news/why-office-civil-rights-april-dear-colleague-letter-was-2011s-biggest-fire-fight (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- U.S. Department of Education. Questions and Answers on Title IX Sexual Violence. 2014. Available online: https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/qa-201404-title-ix.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- U.S. Department of Education. Dear Colleague. 2017. Available online: https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/ED-Dear-Colleague-Title-IX-201709.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Meckler, L. 18 States File Suit over New Rules Governing Campus Sexual Assault Allegations. The Washington Post, 4 June 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/18-states-file-suit-over-new-rules-governing-campus-sex-assault-allegations/2020/06/04/a32aace6-a21f-11ea-9590-1858a893bd59_story.html (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Tyler, T.R. Procedural Justice, Legitimacy, and the Effective Rule of Law. Crime Justice 2003, 30, 283–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.M.; Andrade, J.; De Castro Rodrigues, A. The Psychological Impact of Restorative Justice Practices on Victims of Crimes—A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 1929–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, D. Balancing Justice Goals: Restorative Justice Practitioners’ Views. Contemp. Justice Rev. 2016, 19, 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, M.P. The RESTORE Program of Restorative Justice for Sex Crimes: Vision, Process, and Outcomes. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 1623–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, D.R.; Shackford-Bradley, J.; Wilson, R.; Williamsen, K. Campus PRISM: A Report on Promoting Restorative Initiatives for Sexual Misconduct on College Campuses. Sch. Leadersh. Educ. Sci. Fac. Scholarsh. 2016, 36, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.K.; Chamberlain, J. “There Ought to Be a Law!”: Understanding Community Sentiment. In Handbook of Community Sentiment; Miller, M.K., Blumenthal, J.A., Chamberlain, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedina, L.; Holmes, J.L.; Backes, B.L. Campus Sexual Assault: A Systematic Review of Prevalence Research From 2000 to 2015. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 19, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, H.; Sherman, L.W. Repairing the Harm: Victims and Restorative Justice. Utah Law Rev. 2003, 1, 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- JASP Team. A Fresh Way to do Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update, 10th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E.R.; Adelson, J.L.; Owen, J. Gender Balance, Representativeness, and Statistical Power in Sexuality Research Using Undergraduate Student Samples. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A.S.; Broussard, K.A.; Sterns, J.L.; Sanders, K.K.; Shardy, J.C. Who Are We Studying? Sample Diversity in Teaching of Psychology Research. Teach. Psychol. 2015, 42, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Fall Enrollment: Enrollment Trends by Race/Ethnicity and Gender. 2025. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/SummaryTables/report/270?templateId=2701&years=2023,2022,2021,2020,2019,2018,2017,2016,2015,2014&expand_by=1&tt=aggregate&instType=1&sid=77a8d6b8-b4f0-438d-9d2a-28be33ebc24b (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Clay, R.A. Women Outnumber Men in Psychology, but Not in the Field’s Top Echelons. Monit. Psychol. 2017, 48, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, J.; Mendle, J.; Lindquist, K.A.; Schmader, T.; Clark, L.A.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Akinola, M.; Atlas, L.; Barch, D.M.; Barrett, L.F.; et al. Future of Women in Psychological Science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 483–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zosky, D. “Walking in Her Shoes”: The Impact of Victim Impact Panels on Perpetrators of Intimate Partner Violence. Vict. Offenders 2018, 13, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, I.A.; Zajac, G. The Implementation of Circles of Support and Accountability in the United States. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 25, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, E.C.; Koss, M.P. Title IX and Restorative Justice as Informal Resolution for Sexual Misconduct. In Handbook of Interpersonal Violence and Abuse Across the Lifespan; Geffner, R., White, J.W., Hamberger, L.K., Rosenbaum, A., Vaughan-Eden, V., Vieth, V.I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 4153–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiste, K.B. The Origins of Modern Restorative Justice: Five Examples from the English-Speaking World. UBCL Rev. 2013, 46, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, J.; Bonham, G. Restorative Justice in Canada and the United States: A Comparative Analysis. J. Inst. Justice Int. Stud. 2006, 6, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, L. Restorative Justice System: A Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Law 2017, 3, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).